This study demonstrates that the transcription factor basic helix-loop-helix family member e40 (Bhlhe40) is essential during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection to specifically regulate Il10 expression, revealing the importance of strict control of IL-10 production by innate and adaptive immune cells during infection.

Abstract

The cytokine IL-10 antagonizes pathways that control Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection. Nevertheless, the impact of IL-10 during Mtb infection has been difficult to decipher because loss-of-function studies in animal models have yielded only mild phenotypes. We have discovered that the transcription factor basic helix-loop-helix family member e40 (Bhlhe40) is required to repress Il10 expression during Mtb infection. Loss of Bhlhe40 in mice results in higher Il10 expression, higher bacterial burden, and early susceptibility similar to that observed in mice lacking IFN-γ. Deletion of Il10 in Bhlhe40−/− mice reverses these phenotypes. Bhlhe40 deletion in T cells or CD11c+ cells is sufficient to cause susceptibility to Mtb. Bhlhe40 represents the first transcription factor found to be essential during Mtb infection to specifically regulate Il10 expression, revealing the importance of strict control of IL-10 production by innate and adaptive immune cells during infection. Our findings uncover a previously elusive but significant role for IL-10 in Mtb pathogenesis.

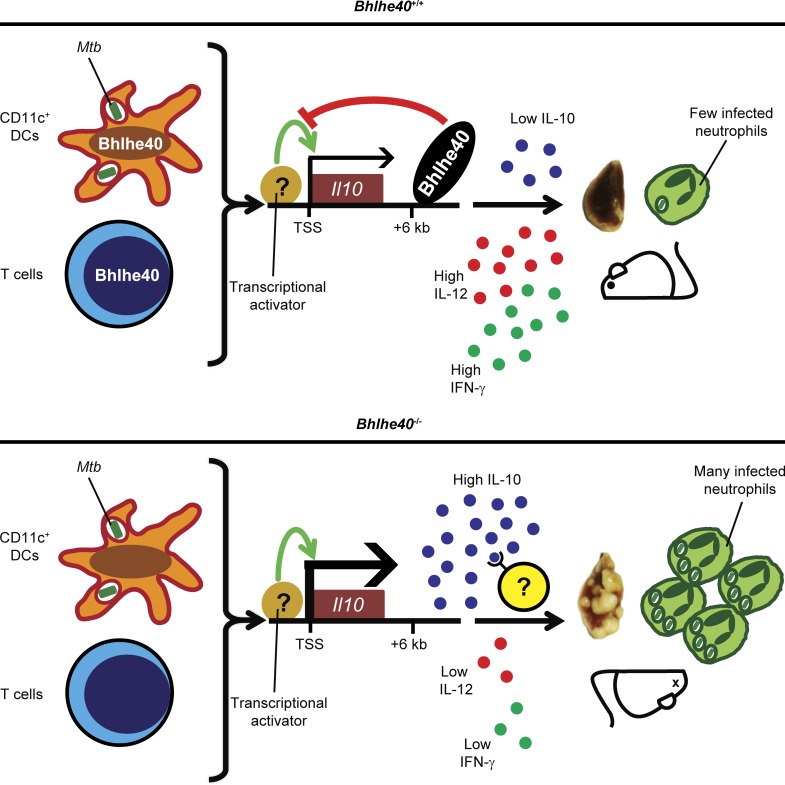

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Host immune responses mediate both the disease outcome and the pathology of tuberculosis (TB) caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection. IFN-γ signaling through the transcription factor STAT1 is essential for the control of mycobacterial infections in humans and mice (Cooper et al., 1993; Flynn et al., 1993; MacMicking et al., 2003; Bustamante et al., 2014). IL-10 is an immunoregulatory cytokine produced by innate and adaptive immune cell types (Gabryšová et al., 2014; Moreira-Teixeira et al., 2017) that antagonizes IFN-γ–associated pathways by suppressing macrophage responsiveness to IFN-γ (Gazzinelli et al., 1992), modulating T-helper (TH) 1 cell IFN-γ production (Turner et al., 2002; Beamer et al., 2008; Redford et al., 2010), and restricting production of the hallmark TH1-inducing cytokine IL-12 (Roach et al., 2001; Demangel et al., 2002; Schreiber et al., 2009). IL-10 can also inhibit dendritic cell (DC) migration (Demangel et al., 2002) and limit secretion of myeloid cell–derived proinflammatory cytokines (de Waal Malefyt et al., 1991). Global loss-of-function studies have demonstrated a detrimental role for Il10 expression in the control of chronic Mtb infection in mice, although the magnitude of this effect appears dependent on the genetic background and is generally mild (Roach et al., 2001; Beamer et al., 2008; Redford et al., 2010). More recently, conditional deletion of Il10 in T cells or CD11c+ cells showed that IL-10 production by these two cell types exacerbates Mtb infection (Moreira-Teixeira et al., 2017). Overexpression of IL-10 in mice has also supported a negative role for IL-10 in controlling mycobacterial infection, although differences in genetic background, transgenic (Tg) promoters, and mycobacterial species used have resulted in an unclear picture (Murray et al., 1997; Feng et al., 2002; Turner et al., 2002; Schreiber et al., 2009).

Given the potential for IL-10 to negatively impact protective immune responses, cell-intrinsic mechanisms likely exist to regulate IL-10 expression. However, the factors required for this regulation remain poorly understood. Mtb directly stimulates IL-10 production from monocytes, macrophages, DCs, and neutrophils via pattern-recognition receptor signaling (Redford et al., 2011). In addition, different TH cell subsets produce IL-10 in response to distinct combinations of cytokines (Gabryšová et al., 2014). These signals lead to the binding of diverse transcription factors at various promoter and enhancer elements within the Il10 locus to activate transcription within myeloid and lymphoid cells (Saraiva and O’Garra, 2010; Gabryšová et al., 2014; Hörber et al., 2016). Much less is known about transcriptional pathways that limit the production of IL-10 (Iyer and Cheng, 2012). In this study, we report that the transcription factor basic helix-loop-helix family member e40 (Bhlhe40) serves an essential role in resistance to Mtb infection by repressing Il10 expression in both T cells and myeloid cells.

Results

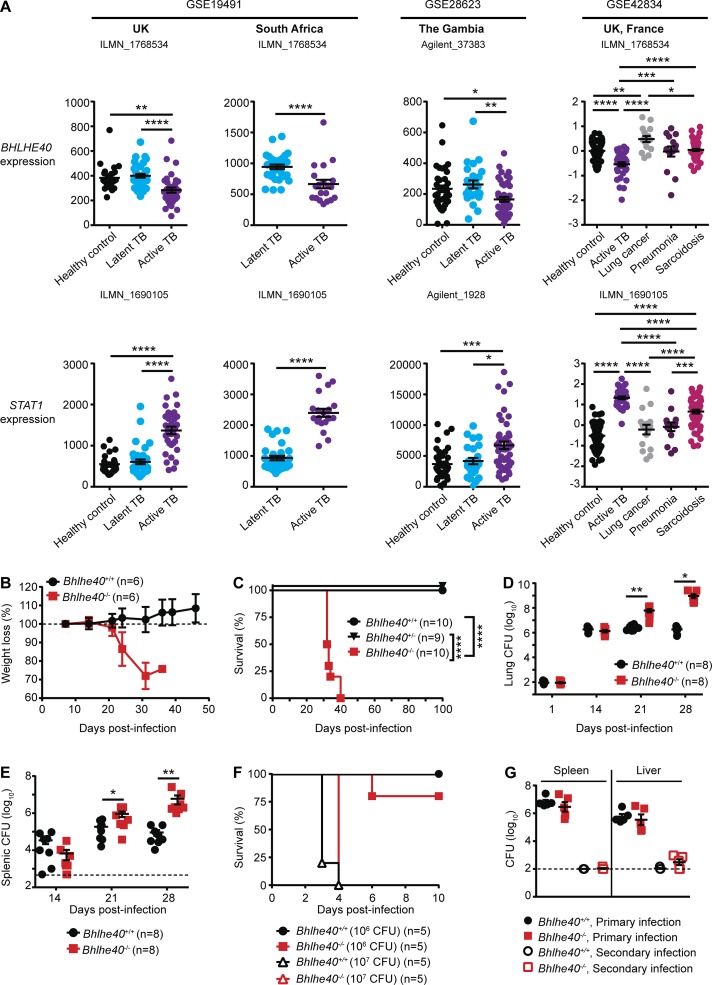

Bhlhe40 is required to control Mtb infection

We have previously shown that the transcription factor Bhlhe40 regulates cytokine production by T cells in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (Lin et al., 2014, 2016). When we analyzed publicly available whole-blood gene expression datasets (Berry et al., 2010; Maertzdorf et al., 2011; Bloom et al., 2013), we found that BHLHE40 transcripts were present at a significantly lower abundance in patients with active TB as compared with healthy controls, those with latent TB infection, or those with lung cancer, pneumonia, or sarcoidosis (Fig. 1 A). This expression pattern contrasted with that of STAT1, whose expression was significantly increased in patients with active TB (Fig. 1 A) as previously noted (Berry et al., 2010; Bloom et al., 2013). This finding of decreased BHLHE40 expression in patients with active TB led us to investigate a role for this transcription factor during Mtb infection in mice. We infected Bhlhe40+/+, Bhlhe40+/−, and Bhlhe40−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background with the Mtb Erdman strain and monitored morbidity and mortality. Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40+/− mice displayed no signs of morbidity and survived beyond 100 d postinfection (dpi). Bhlhe40−/− mice began losing weight at ∼21 dpi and succumbed to infection between 32 and 40 dpi with a median survival time of 33 d (Fig. 1, B and C). This severe susceptibility phenotype is similar to that of mice lacking STAT1 (MacMicking et al., 2003) and is more severe than that of mice lacking NF-κB p50 (Yamada et al., 2001), both of which are central transcriptional regulators of the immune system. By 21 dpi, Mtb CFUs in Bhlhe40−/− mice were 23-fold higher in the lung and fivefold higher in the spleen as compared with Bhlhe40+/+ mice (Fig. 1, D and E). The differences in Mtb CFUs in both organs became even more pronounced at 28 dpi, demonstrating an ongoing defect in the ability of Bhlhe40−/− mice to control Mtb replication. Upon infection with the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, Bhlhe40−/− mice showed no increased susceptibility (Fig. 1, F and G) and mounted a robust response to secondary L. monocytogenes challenge (Fig. 1 G), indicating that their susceptibility to Mtb was caused by an impaired response specific to this pathogen.

Figure 1.

Bhlhe40 is required to control Mtb infection in mice. (A) Expression of BHLHE40 and STAT1 in human whole blood in healthy controls or patients with latent TB, active TB, or other lung diseases. Data are derived from the analysis of the indicated publicly available GEO datasets using the indicated probe sets. (B–E) Bhlhe40+/+, Bhlhe40+/−, and Bhlhe40−/− mice were infected with 100–200 CFU aerosolized Mtb and monitored for body weight (B; n = 6 per group), survival (C; n = 9–10 per group), pulmonary Mtb burden (D; n = 8 per group), and splenic Mtb burden (E; n = 8 per group). (F) Mice were infected with 106 or 107 CFU of L. monocytogenes i.v. and monitored for survival (n = 5 per group). (G) Mice were infected with 106 CFU i.v., and L. monocytogenes burden in the spleen and liver was assessed at 3 d after primary or secondary infection (n = 5 per group). The dotted lines in E and G indicate limits of detection (500 [E] and 100 [G] CFU). Each point represents data from one human or mouse. The mean ± SEM is graphed. Statistical differences were determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, unpaired one-way ANOVA, or unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test (A), log-rank Mantel-Cox test (C and F), and two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test for normally distributed groups or two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test for nonnormally distributed groups (D, E, and G). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Data are from one (F and G) or two independent experiments (B–E).

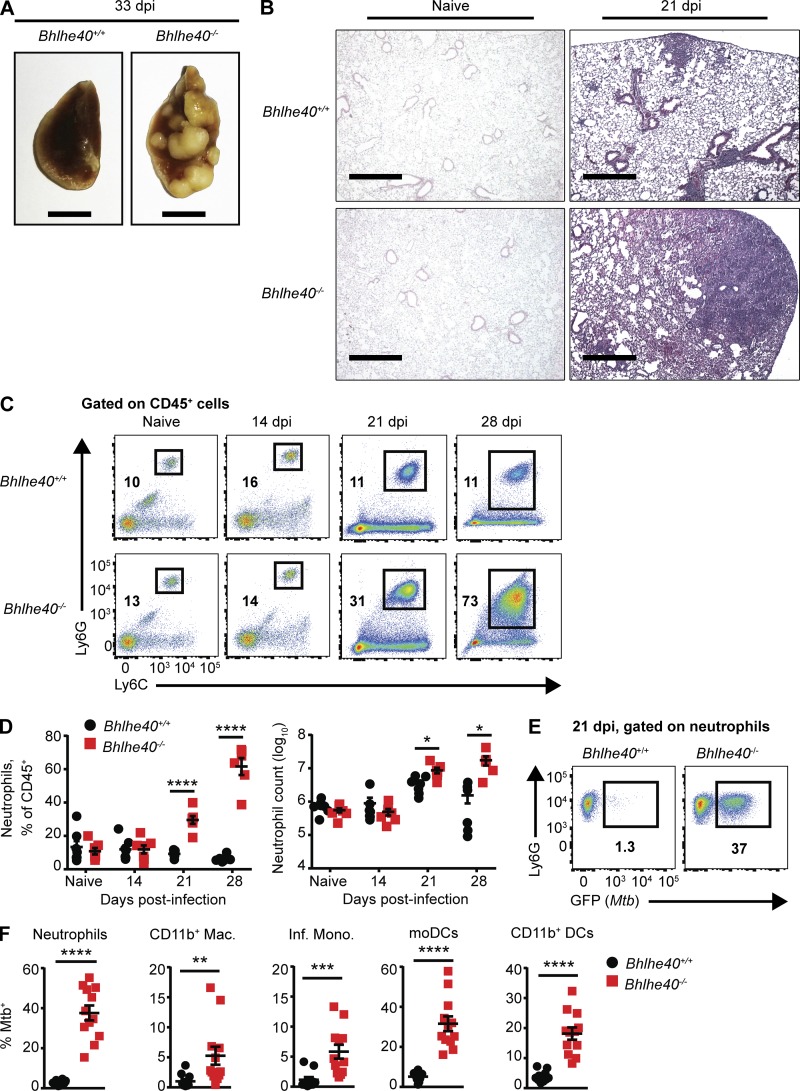

Bhlhe40 deficiency leads to neutrophil-dominated inflammation

Shortly before succumbing to infection, it was evident by gross examination that Bhlhe40−/− lungs had developed larger lesions than Bhlhe40+/+ lungs (Fig. 2 A). Histological analysis confirmed that although there were no differences in pulmonary inflammation before infection, the lungs of Bhlhe40−/− mice had developed larger neutrophil- and acid-fast bacilli-rich lesions with more widespread inflammation than Bhlhe40+/+ lungs by 21 dpi (Figs. 2 B and S1 A). We analyzed these differences further by performing flow cytometry on the immune cell populations present in the lungs of mice before and after Mtb infection. By 21 dpi, neutrophils were the predominant CD45+ cell type in the lungs of Bhlhe40−/− mice, and the absolute number of neutrophils in Bhlhe40−/− lungs was three times greater than in Bhlhe40+/+ lungs (Fig. 2, C and D). The number and frequency of neutrophils in the lungs of Bhlhe40−/− mice further increased as the infection progressed (Fig. 2, C and D). The number of CD11b+Ly6Chigh monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs) was 12-fold lower in Bhlhe40−/− mice at 21 dpi, suggesting that Bhlhe40 may regulate the development, recruitment, or survival of this population (Fig. S1 B). There were no significant differences in the populations sizes of other myeloid or lymphoid cell types analyzed at 21 dpi (Fig. S1 B), nor were there any differences in the frequency of Mtb antigen-specific T cells in the lungs or mediastinal lymph nodes (Fig. S1 C).

Figure 2.

Bhlhe40 deficiency leads to a neutrophil-dominated inflammatory response and high frequencies of infected myeloid cells. (A) Pulmonary gross pathology was assessed at 33 dpi. Bars, 5 mm. (B) Histopathology was visualized by H&E staining of lungs before infection or at 21 dpi. Images shown are at 4× magnification and are representative of two independent experiments with three biological replicates per experiment. Bars, 500 µm. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots for neutrophils as a percentage of the total CD45+ population in Bhlhe40+/+ or Bhlhe40−/− lungs before infection and at 14, 21, and 28 dpi. (D) Absolute count and percentage of the total CD45+ population for neutrophils in Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− lungs before infection (n = 7 per group) and at 14 (n = 7 per group), 21 (n = 7 per group), and 28 dpi (n = 6 per group). (E) Representative flow cytometry plots for GFP (Mtb)–positive neutrophils in Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− lungs at 21 dpi. (F) Frequency of GFP (Mtb)–positive cells in Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− myeloid lung populations at 21 dpi (n = 10–12 per group). Mac., macrophage; Inf. Mono., inflammatory monocyte. (D and F) Each point represents data from one mouse. The mean ± SEM is graphed. Statistical differences were determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test for normally distributed groups or two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test for nonnormally distributed groups as appropriate. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Data are from or representative of two (A–D) or five (E and F) independent experiments.

The timing of the increased inflammation correlated with our initial observation of higher Mtb burden in the lungs of Bhlhe40−/− mice, leading us to investigate whether the accumulating myeloid cells were infected with Mtb. We infected Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− mice with a strain of Mtb Erdman that stably expresses GFP and monitored the number and frequency of Mtb-infected cells at 21 dpi. Neutrophils, CD11b+ macrophages, inflammatory monocytes, moDCs, and CD11b+ DCs were all infected at a higher frequency in Bhlhe40−/− lungs compared with Bhlhe40+/+ lungs (Fig. 2, E and F). Absolute numbers of infected neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes, and CD11b+ DCs were also significantly higher in Bhlhe40−/− lungs (Fig. S1 D), suggesting that Mtb residing within these cell types accounts for the difference in pulmonary Mtb burden in Bhlhe40−/− lungs at 21 dpi. Infected Bhlhe40−/− neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes, moDCs, and CD11b+ DCs also exhibited an increase in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for GFP compared with infected Bhlhe40+/+ neutrophils, suggesting that they harbored more Mtb on a per-cell basis (Fig. S1 E).

To test whether the influx of neutrophils contributed to the susceptibility of Bhlhe40−/− mice, we used an anti-Ly6G monoclonal antibody to specifically deplete neutrophils between 10 and 30 dpi (Kimmey et al., 2015). Neutrophil-depleted Bhlhe40−/− mice did not exhibit any improvements in morbidity, survival time, or control of Mtb replication (Fig. S1, F–H). Therefore, although neutrophils serve as a prominent replicative niche for Mtb, they are not the sole cause of susceptibility to Mtb infection in Bhlhe40−/− mice.

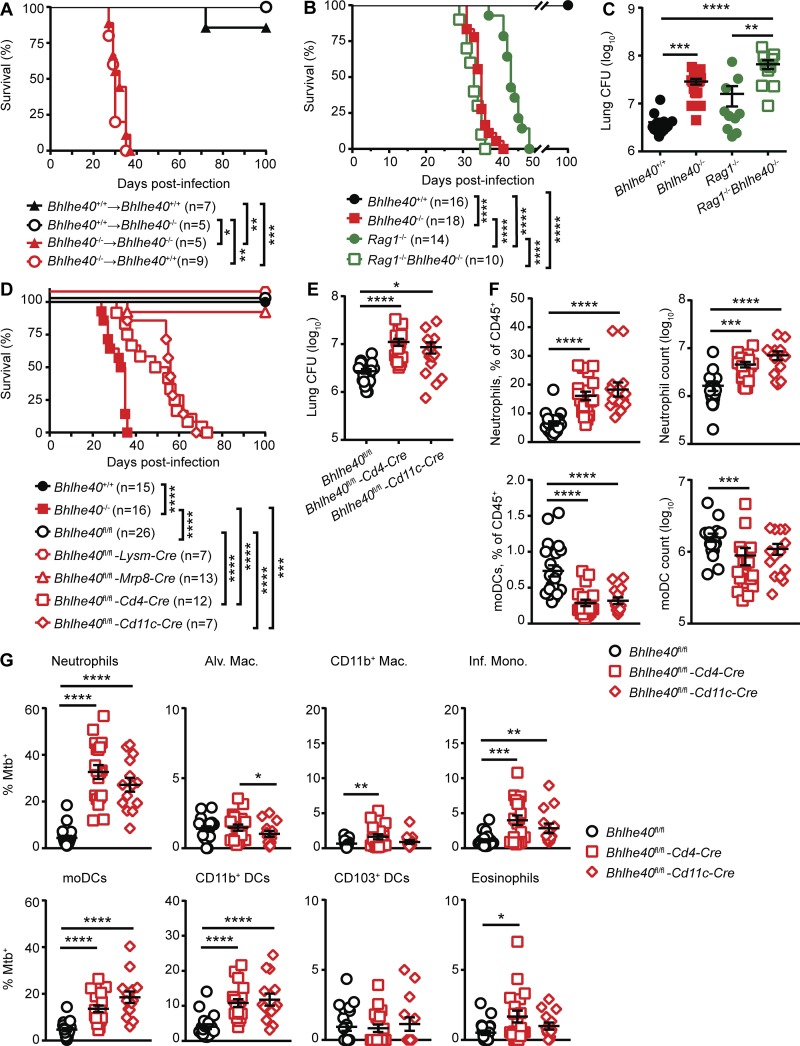

Bhlhe40 functions in innate and adaptive immune cells

Bhlhe40 is expressed in specific immune cell populations and in nonhematopoietic tissues (Ow et al., 2014). To dissect which cells required Bhlhe40 expression during Mtb infection, we first generated reciprocal and control bone marrow chimeric mice, infected them with Mtb, and monitored for survival (Fig. 3 A). As expected, all but one Bhlhe40+/+→Bhlhe40+/+ chimeric mouse survived beyond 100 dpi, and Bhlhe40−/−→Bhlhe40−/− chimeras succumbed between 27 and 35 dpi (median survival time of 33 d). Bhlhe40+/+→Bhlhe40−/− chimeras also survived past 100 dpi, whereas Bhlhe40−/−→Bhlhe40+/+ chimeras died between 29 and 37 dpi (median survival time of 32 d), similar to the Bhlhe40−/−→Bhlhe40−/− chimeras. These data demonstrate a specific role for Bhlhe40 in radiosensitive hematopoietic cells during Mtb infection.

Figure 3.

Bhlhe40 functions in both innate and adaptive immune cells to control Mtb infection. (A) Bhlhe40+/+ or Bhlhe40−/− mice were lethally irradiated, reconstituted with Bhlhe40+/+ or Bhlhe40−/− bone marrow, and monitored for survival after Mtb infection (n = 5–9 per group). (B and C) Bhlhe40+/+, Bhlhe40−/−, Rag1−/−, or Rag1−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice were infected with Mtb and monitored for survival (B; n = 10–18 per group) or lung Mtb burden at 21 dpi (C; n = 10–17 per group). (D–G) Bhlhe40+/+, Bhlhe40−/−, Bhlhe40fl/fl, Bhlhe40fl/fl-Lysm-Cre, Bhlhe40fl/fl-Mrp8-Cre, Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre, and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre mice were infected with Mtb and monitored for survival (D; n = 7–26 per group), lung Mtb burden at 21 dpi (E; n = 14–21 per group), lung neutrophil and moDC absolute count along with percentage of the total CD45+ population at 21 dpi (F; n = 14–21 per group), and frequency of GFP (Mtb)–positive lung cells at 21 dpi (G; n = 14–21 per group). Mac., macrophage; Inf. Mono., inflammatory monocyte; Alv. Mac., alveolar macrophage. (A, B, and D) Each point represents data from one mouse, and the mean ± SEM is shown. The number of biological replicates is indicated in parentheses. Statistical differences were determined by log-rank Mantel-Cox test. In D, Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre mice were compared with Bhlhe40fl/fl, Bhlhe40−/−, and each other. (C, E, and G) Statistical differences were determined by one-way unpaired ANOVA with Tukey’s post test for normally distributed groups or unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test for nonnormally distributed groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Data are from two (A), four (B), five (C), or seven (D–G) independent experiments.

To determine which hematopoietic cells express Bhlhe40 during Mtb infection, we used Bhlhe40-GFP reporter mice (Bhlhe40GFP; Schmidt et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2016). We monitored GFP expression as a proxy for Bhlhe40 expression in the lungs of naive and Mtb-infected Bhlhe40GFP mice. Sizeable fractions of neutrophils, alveolar macrophages, CD11b+ DCs, CD103+ DCs, and eosinophils expressed GFP both before infection and at 21 dpi (Fig. S2), with smaller fractions of CD11b+ macrophages, moDCs, B cells, and CD8+ T cells also showing this pattern of expression. Therefore, these cell types constitutively express Bhlhe40, and this expression pattern does not change during Mtb infection. In contrast, CD4+ T cells in naive mice expressed very little Bhlhe40, but at 21 dpi, Bhlhe40 levels increased in this cell type (Fig. S2). These data show that Bhlhe40 is expressed in both myeloid and lymphoid cells during Mtb infection.

Bhlhe40 expression is required in CD4+ T cells to regulate cytokine production in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of autoimmunity (Martínez-Llordella et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2014). However, Bhlhe40−/− mice succumbed to Mtb infection between 32 and 40 dpi, which is earlier than Rag1−/− mice that lack mature B and T cell and that succumb to Mtb infection between 46 and 50 dpi (Nandi and Behar, 2011). The timing of the death of Mtb-infected Bhlhe40−/− mice suggests that there is a defect in the innate immune response to Mtb, as it preceded the point at which adaptive immunity is required, or the presence of pathological T cells is leading to earlier death than would occur in the absence of T cells, as previously observed in Pdcd1−/− mice (Barber et al., 2011).

To measure the contribution of Bhlhe40 to host resistance in the absence of mature B and T cells, we compared the survival of Mtb-infected Bhlhe40+/+, Bhlhe40−/−, Rag1−/−, and Rag1−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice. Rag1−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice (median survival time of 33 d) were significantly more susceptible than Rag1−/− mice (median survival time of 43 d) to Mtb infection and succumbed to infection at the same time as Bhlhe40−/− mice (Fig. 3 B). These data demonstrate that Bhlhe40 is required during the innate immune response in the absence of T cells to prolong survival during Mtb infection. Mtb CFUs were fourfold higher in Rag1−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice compared with Rag1−/− mice at 21 dpi (Fig. 3 C), and the frequency of neutrophils in the lungs of Rag1−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice was also significantly elevated (Fig. S3 A). The frequency of infected neutrophils, CD11b+ macrophages, and moDCs was significantly higher in Rag1−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice at 21 dpi (Fig. S3 B). We also observed significantly higher MFIs for GFP in Rag1−/−Bhlhe40−/− neutrophils, CD11b+ macrophages, inflammatory monocytes, and CD11b+ DCs, suggesting that these cell types harbored more Mtb on a per-cell basis compared with Rag1−/− cells (Fig. S3 C). Therefore, loss of Bhlhe40 in innate immune cells compromises their ability to control inflammation and Mtb replication independent of adaptive immunity.

To determine more precisely which cells require Bhlhe40 expression to control Mtb infection, we infected mice that conditionally delete Bhlhe40 in specific cell types. After Mtb infection, Bhlhe40fl/fl-Lysm-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Mrp8-Cre mice showed no signs of morbidity (Fig. S3 D) and survived past 100 dpi (Fig. 3 D), indicating that loss of Bhlhe40 in LysM+ or Mrp8+ cells was not sufficient to generate susceptibility to infection. In contrast, Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre mice succumbed to infection at 34–62 d (median survival time of 56 d) and 31–73 d (median survival time of 52 d), respectively (Fig. 3 D). Therefore, Bhlhe40 expression in both T cells and CD11c+ cells is required to control Mtb infection. Given that the Lysm promoter can drive conditional deletion in alveolar macrophages but deletes poorly in myeloid DCs, whereas the Cd11c promoter deletes equally well in both alveolar macrophages and DCs (Abram et al., 2014), one interpretation is that loss of Bhlhe40 in alveolar macrophages is not sufficient to cause susceptibility and that loss of Bhlhe40 in DCs contributes to the susceptibility observed in Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre mice.

We next analyzed susceptible Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre mice to determine how loss of Bhlhe40 in CD11c+ or T cells contributed to phenotypes observed in Bhlhe40−/− mice. By 21 dpi, pulmonary Mtb burden in Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre mice was four- and threefold higher than Bhlhe40fl/fl controls, respectively (Fig. 3 E). Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre mice also exhibited an increase in the frequency and absolute number of pulmonary neutrophils (Fig. 3 F). The frequency of moDCs was significantly lower in Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre lungs, but the absolute number of moDCs was decreased in Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre lungs only, suggesting that loss of Bhlhe40 in T cells leads to the decreased number of moDCs observed in Bhlhe40−/− mice (Figs. 3 F and S1 B). Neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes, moDCs, and CD11b+ DCs were infected at a higher frequency in both Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre mice (Fig. 3 G). Although survival, Mtb burden, neutrophilic inflammation, and frequency of cellular infection phenotypes were evident in Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre mice, they were less severe than in Bhlhe40−/− mice, suggesting that defects caused by Bhlhe40 deficiency in CD11c+ cells, T cells, and potentially other cell types combine to undermine protective responses to Mtb.

Bhlhe40 represses IL-10 production after exposure to Mtb

Bhlhe40 has previously been found to regulate cytokine production by CD4+ T cells in the EAE model (Martínez-Llordella et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2014). If Bhlhe40 functions analogously during Mtb infection, Bhlhe40−/− cells could exert a dominant effect on Bhlhe40+/+ cells through the production of secreted cytokines. We tested this by generating mixed bone marrow chimeric mice. Congenically marked Bhlhe40+/+ (CD45.1/.2) recipients were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with a 1:1 mixture of Bhlhe40+/+ (CD45.1/.1) and Bhlhe40−/− (CD45.2/.2) bone marrow cells. Control mice included mixed chimeras generated with Bhlhe40+/+ (CD45.1/.1) and Bhlhe40+/+ (CD45.2/.2) bone marrow cells as well as nonchimeric Bhlhe40+/+ (CD45.2/.2) and Bhlhe40−/− (CD45.2/.2) mice. In mixed chimeras, Bhlhe40−/− bone marrow cells were capable of normal reconstitution of the hematopoietic compartment within the lung (Fig. 4 A). Chimeric mice were infected with GFP-expressing Mtb and analyzed at 21 dpi. Bhlhe40+/+ + Bhlhe40+/+ chimeras controlled Mtb infection with little neutrophilic infiltrate (unpublished data) and a low frequency of neutrophil infection (Fig. 4, B and C). Lungs of mixed Bhlhe40+/+ + Bhlhe40−/− chimeras contained large populations of infiltrating neutrophils of both genotypes (unpublished data). Neutrophils of both genotypes displayed a high frequency of Mtb infection (Fig. 4, B and C), which correlated with a trend toward higher CFUs in the lungs of mixed Bhlhe40+/+ + Bhlhe40−/− chimeras (Fig. S3 E). These results demonstrate that Bhlhe40−/− cells, even when present as only half of all hematopoietic cells, exert a dominant influence in trans on the ability of Bhlhe40+/+ cells to control neutrophil accumulation and Mtb infection.

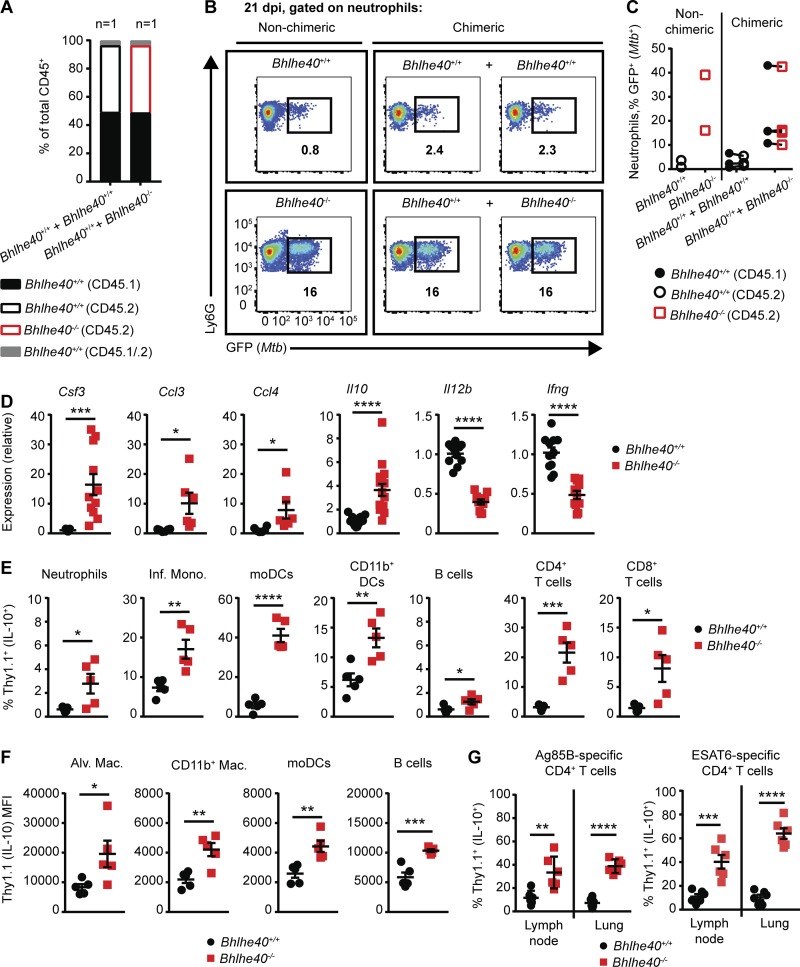

Figure 4.

Multiple immune cells require Bhlhe40 to repress IL-10 production after exposure to Mtb. (A) The frequency of CD45.1+, CD45.2+, and CD45.1+CD45.2+ lung cells in naive mixed bone marrow chimeric mice (n = 1 per group). (B and C) Representative flow cytometry plots (B) and frequency of infected neutrophils in the lungs of nonchimeric and mixed bone marrow chimeric mice infected with GFP-Mtb at 21 dpi (C; n = 2–4 per group). (D) Cytokine transcript levels were assessed at 21 dpi in total lung samples from Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− mice (n = 11 or 16 per group). (E) The frequency of Thy1.1 (IL-10)–expressing immune cells in 10BiT+ Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− lungs at 21 dpi (n = 5 per group). (F) Geometric MFI for FITC (Thy1.1 [IL-10]) on Thy1.1-expressing lung cells at 21 dpi (n = 5 per group). Mac., macrophage; Inf. Mono., inflammatory monocyte; Alv. Mac., alveolar macrophage. (G) Thy1.1-expressing Ag85B- or ESAT6-specific CD4+ T cells as a percentage of the total Ag85B- or ESAT6-specific CD4+ T cell population in the lungs or mediastinal lymph nodes of 10BiT+ Bhlhe40+/+ or Bhlhe40−/− mice at 21 dpi (n = 6 per group). Each point represents data from one mouse except in C, where data from the same mouse is connected by a line. The mean ± SEM is graphed. Statistical differences were determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test for normally distributed groups or two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test for nonnormally distributed groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Data are from one (A) or two (B–G) independent experiments.

These data indicate that Bhlhe40 likely regulates secreted factors such as cytokines or chemokines, which can impact other cells. Therefore, we analyzed cytokine and chemokine levels in total lung samples from Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− mice by quantitative RT-PCR. At 21 dpi, transcripts for the neutrophil-associated cytokines Csf3 (G-CSF), Ccl3 (MIP-1α), and Ccl4 (MIP-1β) were up-regulated in Bhlhe40−/− lungs (Fig. 4 D) as expected given the neutrophil-dominated inflammation observed. We also found that at 21 dpi, Il10 (IL-10) transcript levels were threefold higher in Bhlhe40−/− lungs, and Il12b (IL-12/23p40) and Ifng (IFN-γ) transcript levels were three- and twofold lower in Bhlhe40−/− lungs, respectively, compared with Bhlhe40+/+ lungs (Fig. 4 D). This finding was of particular interest because Bhlhe40 represses Il10 transcription in CD4+ T cells in the EAE model (Lin et al., 2014) and IL-10 has been shown to inhibitIL-12/23p40 and IFN-γ expression during Mtb infection (Roach et al., 2001; Turner et al., 2002; Schreiber et al., 2009; Redford et al., 2010). In the lungs of naive Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− mice, there were no differences in the levels of Ifng and Csf3 transcript, and Il10 and Il12b transcript levels were below the level of detection (unpublished data), indicating that loss of Bhlhe40 impacts expression of these genes during Mtb infection but not in naive mice.

The increased Il10 transcript levels in conjunction with decreased Il12b and Ifng transcript levels in Bhlhe40−/− lungs at 21 dpi indicated that Bhlhe40 could be regulating Il10 expression. To identify the cell types responsible for the increased Il10 expression in Bhlhe40−/− lungs, we used Tg Il10 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-in transgene (10BiT) IL-10 reporter mice (Maynard et al., 2007), where Il10-expressing cells display Thy1.1 on their surface. We observed a similar distribution of Il10-expressing cells in 10BiT+ Bhlhe40+/+ mice as reported in a recent study that used these reporter mice to characterize sources of IL-10 before and after Mtb infection (Moreira-Teixeira et al., 2017). We crossed 10BiT and Bhlhe40−/− mice to generate a Bhlhe40−/− 10BiT-positive strain, and then we analyzed Thy1.1 expression as a proxy for Il10 expression. We observed low levels of Thy1.1 expression in naive 10BiT+ Bhlhe40+/+ and 10BiT+ Bhlhe40−/− mice (Fig. S4 A). At 21 dpi, no differences were observed when comparing the absolute number of Thy1.1+ cells, but the frequency of Thy1.1+ neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes, moDCs, CD11b+ DCs, B cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells was significantly higher in Bhlhe40−/− mice (Figs. 4 E and S4, B and C). In addition, when we compared the MFIs for Thy1.1 on Thy1.1+ cells, we found that not only were a higher percentage of Bhlhe40−/− moDCs and B cells expressing Thy1.1, but these cell types also expressed more Thy1.1 on a per-cell basis during Mtb infection (Fig. 4 F). Significantly higher Thy1.1 MFI was also observed on Bhlhe40−/− Thy1.1+ alveolar macrophages and CD11b+ macrophages (Fig. 4 F). The increased frequency of Thy1.1 positivity observed in Bhlhe40−/− CD4+ T cells was even more pronounced in Bhlhe40−/− Mtb–specific CD4+ T cells in the mediastinal lymph node and lung, indicating that Mtb-specific CD4+ T cells take on an immunosuppressive phenotype in the absence of Bhlhe40 (Fig. 4 G). These data demonstrated that the frequency and per-cell expression of Il10 was increased in multiple Bhlhe40−/− myeloid and lymphoid populations.

Bhlhe40 suppresses IL-10 expression in myeloid cells in vitro

We sought to identify an in vitro myeloid cell culture system that recapitulates the effects of Bhlhe40 deficiency on IL-10 production in response to Mtb. We cultured Bhlhe40+/+ bone marrow cells with GM-CSF or macrophage CSF (M-CSF) and determined by Western blot analysis that only cells cultured with GM-CSF, which comprise a mixture of granulocytes, macrophage-like cells, and DC-like cells (Helft et al., 2015; Poon et al., 2015), express Bhlhe40 (Fig. 5 A). Analysis of GM-CSF– and M-CSF–cultured cells from Bhlhe40GFP reporter mouse bone marrow confirmed that only GM-CSF–cultured bone marrow–derived cells expressed GFP (Fig. 5 B). This expression of Bhlhe40 in granulocytes, macrophage-like cells, and DC-like cells cultured with GM-CSF may relate to the expression of Bhlhe40 by these cell types in the lung (Fig. S2; Heng et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2016), where GM-CSF is abundant and plays an important part in the development and function of lung myeloid cells (Kopf et al., 2015). Loss of Bhlhe40 did not significantly affect the ability of GM-CSF–cultured cells to control Mtb replication in the presence or absence of IFN-γ (Fig. S5 A), suggesting that Bhlhe40 is dispensable for the ability of these cell types to control Mtb replication.

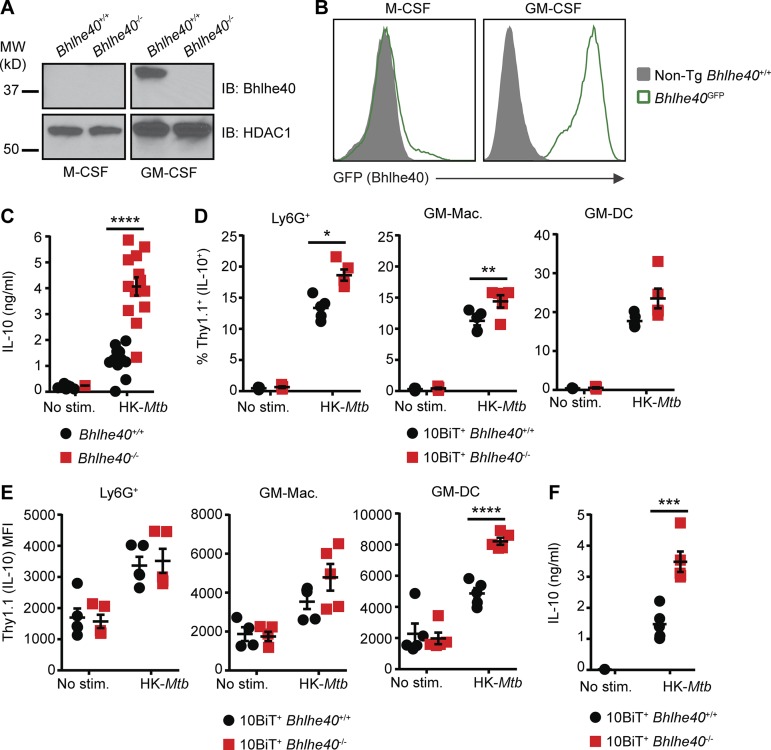

Figure 5.

Bhlhe40 represses IL-10 in myeloid cells after Mtb stimulation. (A and B) Bhlhe40+/+, Bhlhe40−/−, and Bhlhe40GFP bone marrow cells were differentiated in the presence of M-CSF or GM-CSF and analyzed for expression of Bhlhe40 by immunoblot (IB) with HDAC1 as a loading control (A) or GFP as a reporter for Bhlhe40 expression (B). MW, molecular weight. (C) Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− GM-CSF–cultured bone marrow–derived cells were left unstimulated or stimulated with heat-killed (HK) Mtb (n = 13 per group) for 24 h, and culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-10 production by ELISA. IL-10 expression in six unstimulated Bhlhe40+/+ and 12 unstimulated Bhlhe40−/− samples was below the limit of detection (∼0.1 ng/ml). (D–F) 10BiT+ Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− bone marrow cells were differentiated in the presence of GM-CSF and stimulated with heat-killed Mtb antigen for 24 h. Thy1.1 was assessed on three subpopulations of cells within the GM-CSF cultures. These included Ly6G+ cells, GM-macrophages (GM-Macs; identified as CD11c+CDllbhiMHC-IImid), and GM-DCs (identified as CD11c+CD11bmidMHC-IIhi). (D) Frequency of Thy1.1+ (IL-10+) cells after 24 h of stimulation (n = 5 per group). (E) Geometric MFI for Thy1.1 on Thy1.1+ cells after 24 h of stimulation (n = 5 per group). (F) Culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-10 production by ELISA (n = 5 per group). IL-10 expression in four unstimulated 10BiT+ Bhlhe40+/+ and five unstimulated 10BiT+ Bhlhe40−/− samples was below the limit of detection (∼0.1 ng/ml). Each point represents data from cells derived from a single mouse. The mean ± SEM is graphed. Statistical differences were determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test for normally distributed groups or two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test for nonnormally distributed groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Data are from or representative of two (A, B, and D–F) or five (C) independent experiments.

We next assessed IL-10 expression from Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− cells cultured with GM-CSF. In the absence of stimulation with heat-killed Mtb, minimal IL-10 protein was detected in culture supernatants (Fig. 5 C). In contrast, Bhlhe40−/− GM-CSF–cultured bone marrow–derived cells stimulated with heat-killed Mtb for 24 h produced significantly more IL-10 than Bhlhe40+/+ cells (Fig. 5 C). We also stimulated 10BiT+ Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− GM-CSF–cultured cells with heat-killed Mtb, assessed Thy1.1 expression by flow cytometry, and measured IL-10 in culture supernatants by ELISA. Mtb stimulation increased the frequency of Thy1.1+ cells in both Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− cultures relative to unstimulated cultures, and this increase was greater in Bhlhe40−/− cells compared with Bhlhe40+/+ cells (Fig. 5 D). Mtb stimulation also increased the amount of Thy1.1 expression on a per-cell basis, where Bhlhe40−/− CD11c+CD11b+MHC-IIhigh (GM-DC) cells exhibited a 1.7-fold higher MFI than Bhlhe40+/+ GM-DCs (Fig. 5 E). ELISAs confirmed that 10BiT+ Bhlhe40−/− cells secreted more IL-10 than 10BiT+ Bhlhe40+/+ cells after stimulation with heat-killed Mtb (Fig. 5 F). These experiments confirm that loss of Bhlhe40 in GM-CSF–cultured cells results in higher levels of IL-10 production.

Bhlhe40 binds directly to the Il10 locus in TH1 cells and myeloid cells

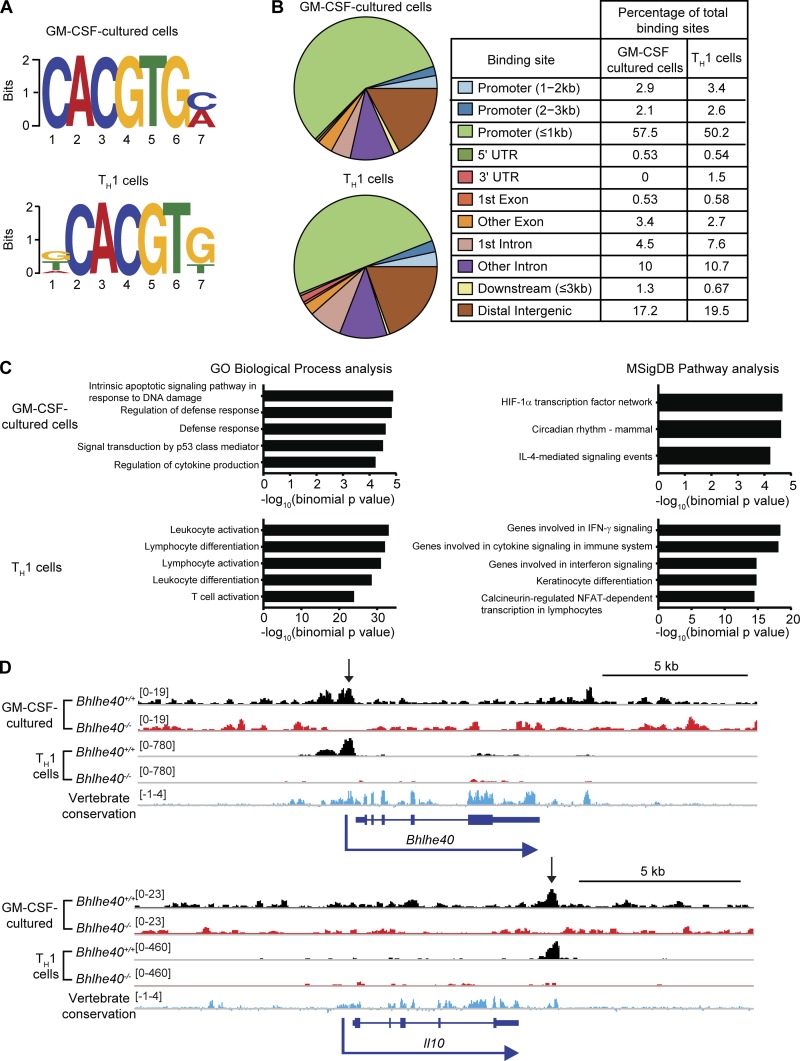

We performed chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) experiments in in vitro–polarized TH1 cells and GM-CSF–cultured bone marrow–derived cells to interrogate whether Bhlhe40 directly binds to the Il10 locus in these cells as well as to identify other genes that may be directly regulated by Bhlhe40. We performed this research with Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− cells, where Bhlhe40−/− cells served as controls for nonspecific binding by the anti-Bhlhe40 antibody. Bhlhe40 bound 379 sites in Bhlhe40+/+ GM-CSF–cultured cells and 5,532 sites in Bhlhe40+/+ TH1-polarized T cells (Tables S1 and S2). Of these sites, 273 were found in both datasets. Bhlhe40 can directly bind to regulatory DNA elements as a homodimer through recognition of E-box sites, with a preference for the sequence CACGTG (St-Pierre et al., 2002). Motif finding identified the expected E-box (CACGTG) as the most frequent motif present within the peaks identified in both cell types (Fig. 6 A). Analysis of binding sites revealed that Bhlhe40 predominantly bound promoters within 1 kb of the transcriptional start site, introns, and distal intergenic regions (Fig. 6 B). Pathway analysis of predicted Bhlhe40-regulated genes revealed an enrichment in immune activation and cytokine response pathways in both datasets (Fig. 6 C). Bhlhe40 is known to bind a conserved autoregulatory site in the Bhlhe40 promoter (Sun and Taneja, 2000), and this binding site was identified as a peak in both datasets (Fig. 6 D). Importantly, our ChIP-seq experiment identified a Bhlhe40 binding site at +6 kb relative to the transcriptional start site of Il10 in both datasets, coinciding with an evolutionarily conserved region that is close to a +6.45-kb site previously identified as an enhancer element in TH2 cells (Fig. 6 D; Jones and Flavell, 2005). These data suggest that Bhlhe40 directly represses Il10 transcription in myeloid and lymphoid cells through direct binding of a downstream cis-regulatory element. ChIP-seq analysis did not reveal binding of Bhlhe40 to the Il12b locus in either dataset (Tables S1 and S2). Bhlhe40 did not bind the Ifng locus in GM-CSF–cultured cells but bound two sites distal (−33.5 kb and +53.2 kb) to the Ifng transcriptional start site in TH1 cells (Fig. S5 B). These findings suggest that the transcriptional down-regulation of Il12b in Bhlhe40−/− total lung samples (Fig. 4 D) is indirect and likely a result of increased IL-10 signaling, whereas the decreased levels of Ifng may result from either increased IL-10 signaling or T cell–intrinsic loss of direct regulation by Bhlhe40.

Figure 6.

Bhlhe40 directly binds the Il10 locus in myeloid and lymphoid cells. (A–D) Bone marrow cells were differentiated in the presence of GM-CSF and stimulated with heat-killed Mtb for 4 h. CD4+ T cells were TH1 polarized in vitro for 4 d. DNA was immunoprecipitated using anti-Bhlhe40 antibody and sequenced. (A) Sequence motifs present within DNA bound by Bhlhe40 were analyzed by MEME-ChIP. (B) Bhlhe40 binding sites were annotated using ChIPseeker (3.5). (C) Functions of cis-regulatory regions were predicted for Bhlhe40 binding site data using GREAT. The top five most highly enriched gene sets with minimum region-based fold enrichment of 2 and binomial and hypergeometric false discovery rates of ≤0.05 in the Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process and MSigDB Pathway gene sets are displayed for each dataset (in GM-CSF–cultured cells, only three MSigDB Pathway gene sets met these criteria). NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells. (D) ChIP-seq binding tracks for Bhlhe40 at the Bhlhe40 and Il10 loci in Bhlhe40+/+ and Bhlhe40−/− myeloid and lymphoid cells. Vertebrate conservation of each genomic region is displayed in blue, and peaks identified by MACS are indicated by arrows. Bracketed numbers indicate the trace height range. Data are from a single experiment.

IL-10 deficiency protects Bhlhe40−/− mice from Mtb infection

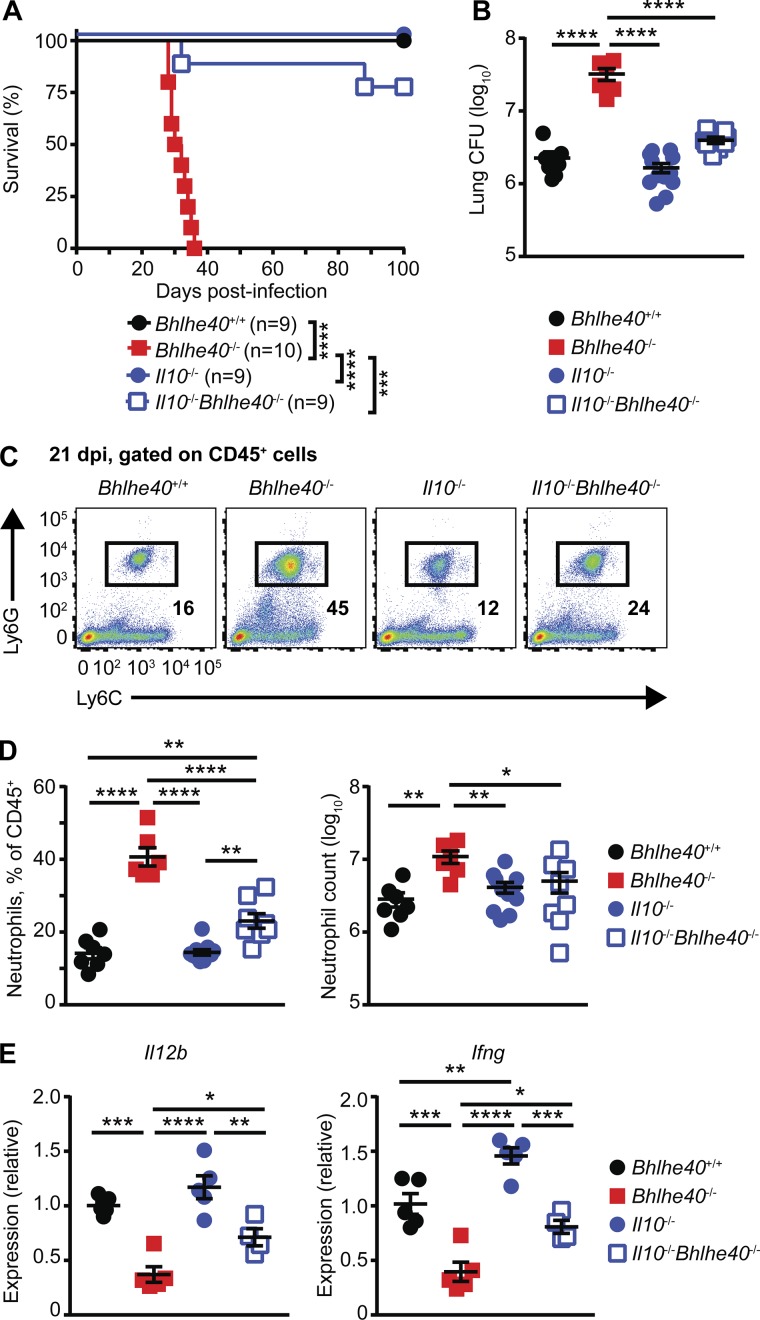

To investigate the role of IL-10 production in the susceptibility of Bhlhe40−/− mice, we generated Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice and compared their survival to Bhlhe40+/+, Bhlhe40−/−, and Il10−/− mice after Mtb infection. The absence of IL-10 signaling resulted in near-complete rescue of the susceptibility phenotype caused by Bhlhe40 deficiency as shown by the significant increase in the median survival time of Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice (>100 d) compared with Bhlhe40−/− mice (31 d; Fig. 7 A). The increased survival of Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice was accompanied by an eightfold decrease in pulmonary Mtb titer in Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− lungs compared with Bhlhe40−/− lungs at 21 dpi (Fig. 7 B). These data demonstrate that the inability of Bhlhe40−/− mice to control Mtb replication is likely caused in large part by higher IL-10 levels. When compared with Bhlhe40−/− lungs, Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− lungs contained a significantly lower frequency and total number of neutrophils (Fig. 7, C and D). However, the frequency of neutrophils in Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− lungs remained higher than in Bhlhe40+/+ or Il10−/− lungs (Fig. 7, C and D). Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− lungs also contained twofold more Il12b and Ifng transcripts than Bhlhe40−/− lungs at 21 dpi, demonstrating that IL-10 signaling was at least partially responsible for the decreased expression of these genes in Bhlhe40−/− lungs (Fig. 7 E). These data establish Bhlhe40 as an essential regulator of Il10 expression in myeloid cells and lymphocytes during Mtb infection and reveal the importance of IL-10 regulation for innate and adaptive immune responses that control Mtb infection.

Figure 7.

IL-10 deficiency protects Bhlhe40−/− mice from Mtb infection. (A and B) Bhlhe40+/+, Bhlhe40−/−, Il10−/−, and Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice were monitored for survival after Mtb infection (A; n = 9–10 per group) or analyzed for pulmonary CFU at 21 dpi (B; n = 6–12 per group). The number of biological replicates is indicated in parentheses. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots for lung neutrophils as percentages of the total CD45+ population at 21 dpi. (D) The absolute neutrophil count and the frequency of neutrophils in the total lung CD45+ population 21 dpi (n = 6–12 per group). (E) Cytokine transcript levels in total lung samples at 21 dpi (n = 4–5 per group). Each point represents data from one mouse. The mean ± SEM is graphed. Statistical differences were determined by log-rank Mantel-Cox test (A) and one-way unpaired ANOVA with Tukey’s post test for normally distributed groups or unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test for nonnormally distributed groups (B, D, and E). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Data are from two (A and E) or four (B and D) independent experiments. Data in C are representative of four independent experiments.

Discussion

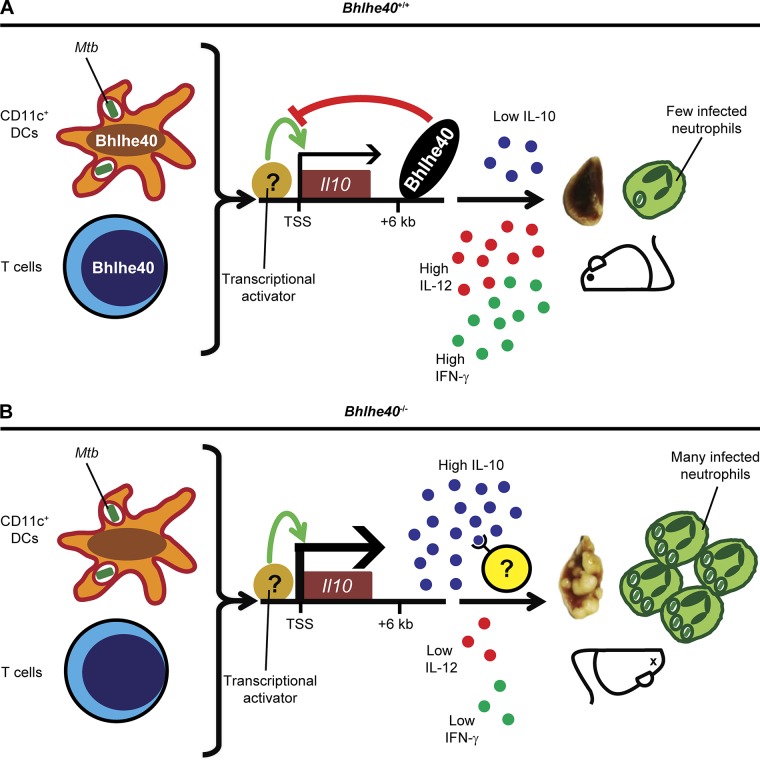

We have identified Bhlhe40 as a transcription factor that is essential for coordinating immune responses that protect the host from Mtb infection. Based on our research, we propose the following model (Fig. 8). During the acute phase of infection, CD11c+ cells encounter Mtb antigens that trigger a putative transcriptional activator to induce Il10 expression, the activity of which is restricted by the binding of Bhlhe40 to a cis-acting regulatory region +6 kb downstream of the Il10 transcriptional start site. The identity of the activator that induces Il10 transcription in the absence of Bhlhe40 during Mtb infection is currently unknown, but may be one of the activators previously described (Gabryšová et al., 2014). In addition, Bhlhe40 is induced in T cells during Mtb infection, where it also represses Il10 transcription. The repression of Il10 expression by Bhlhe40 in these cell types allows for higher expression of Il12b and Ifng, both of which are essential for control of Mtb replication (Cooper et al., 1993; Flynn et al., 1993; Hölscher et al., 2001). These findings represent the first study of roles for Bhlhe40 in the immune response to an infection and within myeloid cells. Additionally, although other negative regulators of Il10 transcription have been described (Riemann et al., 2005; Yee et al., 2005; Villagra et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2010; Krausgruber et al., 2011), Bhlhe40 is the first transcription factor that has been shown to be essential during Mtb infection specifically to regulate Il10 expression. Our findings reveal the importance of controlling IL-10 generation by both innate and adaptive immune cells and shed light on how different levels of IL-10 could impact TB disease in humans.

Figure 8.

Model of Bhlhe40 function during Mtb infection. (A) During Mtb infection, Il10 transcription is restricted by Bhlhe40 in CD11c+ DCs and T cells through direct binding to an enhancer site +6 kb downstream of the Il10 transcriptional start site (TSS). The resulting amount of IL-10 expression is insufficient to compromise host resistance, leading to an immunological stalemate in which Mtb replication is controlled for the remainder of the lifetime of the host. (B) In Bhlhe40−/− mice, the absence of Bhlhe40 in CD11c+ DCs and T cells allows for high levels of Il10 expression. Excessive IL-10 signaling then acts on lung immune cells to suppress the production and protective effects of IL-12 and IFN-γ, both of which are essential for control of Mtb pathogenesis. As a result, in Bhlhe40−/− mice, Mtb lung burdens are higher, and neutrophil-dominated inflammation is uncontrolled, ultimately resulting in susceptibility.

Survival experiments showed that about one quarter of Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre mice recapitulated the very early susceptibility of Bhlhe40−/− mice (Fig. 3 D), with the remainder of these Bhlhe40 conditionally deleted mice dying between 50 and 75 dpi. In the case of the Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre strain, the finding that 4 out of 12 of these mice succumbed at 31–38 dpi (Fig. 3 D), whereas Rag1−/− mice succumbed at ∼45 dpi (Fig. 3 B), indicates that Bhlhe40−/− T cells can be actively pathological and generate a worse outcome than the absence of T cells, likely through the production of a factor such as IL-10. The delay in susceptibility of most of the Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd11c-Cre and Bhlhe40fl/fl-Cd4-Cre mice as compared with Bhlhe40−/− mice could indicate that the susceptibility of Bhlhe40−/− mice is a result of the combination of loss of Bhlhe40 in both CD11c+ and T cells, insufficient ability of the Cd11c and Cd4 promoters to drive Bhlhe40 exon deletion in all Cre-expressing cells, or the ability of Bhlhe40 deficiency in a non-CD11c+ or -CD4+ cell type to enhance susceptibility. IL-10 production by T cells and CD11c+ cells during Mtb infection in mice was recently shown to contribute to host susceptibility (Moreira-Teixeira et al., 2017), further supporting the notion that regulation of Il10 expression in these cell populations would be important during Mtb infection.

Our analyses of Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice revealed that IL-10 deficiency conferred a near-complete rescue of multiple phenotypes associated with the susceptibility of Bhlhe40−/− mice (Fig. 7), indicating that the up-regulation of Il10 transcription in the absence of Bhlhe40 is a major contributor to the susceptibility of these mice. Nonetheless, some phenotypes partially remained in the absence of Il10. For example, although the susceptibility of Bhlhe40+/+ and Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice was not significantly different, we did observe that ∼20% of the Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice succumbed before 100 dpi (Fig. 7 A). Additionally, Il10−/−Bhlhe40−/− mice had a significantly higher frequency of neutrophils in the lungs at 21 dpi compared with Bhlhe40+/+ mice (Fig. 7, C and D). The incomplete rescue of these phenotypes indicates that Bhlhe40 likely regulates the expression of other genes during Mtb infection that impact pathogenesis. Future studies will explore the other Bhlhe40-bound loci identified by ChIP-seq to identify additional Bhlhe40 targets that contribute to the control of Mtb infection.

Patients with active TB have increased levels of IL-10 in their serum (Verbon et al., 1999; Olobo et al., 2001) and lungs (Barnes et al., 1993; Huard et al., 2003; Bonecini-Almeida et al., 2004; Almeida et al., 2009), suggesting a link between increased IL-10 levels and TB disease (Redford et al., 2011). Although it is unclear whether the reduced expression of BHLHE40 in the blood of patients with active TB (Fig. 1 A) is a cause or effect of their disease or related to the higher IL-10 levels found in this form of TB, this correlation agrees with the increased susceptibility of mice lacking Bhlhe40 and suggests that our experiments could be relevant to human Mtb infection.

Materials and methods

Bacterial cultures

Mtb strain Erdman and its derivatives were cultured at 37°C in 7H9 broth (Sigma-Aldrich) or on 7H11 agar (BD) medium supplemented with 10% oleic acid/albumin/dextrose/catalase, 0.5% glycerol, and 0.05% Tween-80 (broth only). GFP-expressing Mtb (GFP-Mtb) was generated by transformation of Mtb strain Erdman with a plasmid (pMV261-kan-GFP) that drives constitutive expression of GFP under the control of the mycobacterial hsp60 promoter. Cultures were grown in the presence of kanamycin to ensure plasmid retention.

L. monocytogenes expressing chicken ovalbumin (LM-Ova) on the 10403S genetic background was a gift from H. Shen (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). Bacteria were grown to mid-logarithmic phase with shaking at 37°C in brain–heart infusion broth (HiMedia Laboratories) before washing and storage as glycerol stocks at −80°C.

Mouse strains

All mice used were on a C57BL/6 background. C57BL/6 (Taconic), B6.SJL (CD45.1; Taconic), Bhlhe40GFP BAC Tg (N10 to C57BL/6; Lin et al., 2016), Bhlhe40−/− (N10 to C57BL/6; Sun et al., 2001), Rag1−/−, Il10−/−, and 10BiT IL-10 reporter mice (Maynard et al., 2007) were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility. Bhlhe40−/− mice were crossed to Rag1−/−, Il10−/−, or 10BiT mice for some experiments.

Bhlhe40fl/fl mice were generated with two loxP sites flanking exon 4 of Bhlhe40. These mice originated as a KO-first promoter-driven mouse line from the Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP) and were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bhlhe40tm1a(KOMP)Wtsi; 024395). These initial mice contained a Bhlhe40 allele with a splice acceptor–LacZ reporter and a Neo cassette flanked by two Frt sites, which were removed by crossing them to B6N.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(FLP1)Dym/J mice (016226; The Jackson Laboratory), leaving behind an allele of Bhlhe40 with a loxP-flanked exon 4. Subsequent crosses yielded Bhlhe40fl/fl mice with no residual Rosa26-Flp transgene. Bhlhe40fl/fl mice were crossed with one of four mouse strains, Mrp8-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(S100A8-cre,-EGFP)1Ilw/J; 021614), Lysm-Cre (B6N.129P2(B6)-Lyz2tm1(cre)Ifo/J; 018956), Cd11c-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Itgax-cre)1-1Reiz/J; 008068), and Cd4-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Cd4-cre)1Cwi/Bflu/J; 022071), all from The Jackson Laboratory.

Age-matched littermate adult mice (9–23 wk of age) of both sexes were used, and mouse experiments were randomized. No blinding was performed during animal experiments. All procedures involving animals were conducted following the National Institutes of Health guidelines for housing and care of laboratory animals, and they were performed in accordance with institutional regulations after protocol review and approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine (protocol 20160094, Immune System Development and Function, and protocol 20160118, Analysis of Mycobacterial Pathogenesis). Washington University is registered as a research facility with the United States Department of Agriculture and is fully accredited by the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The Animal Welfare Assurance is on file with Office for Protection from Research Risks–National Institutes of Health. All animals used in these experiments were subjected to no or minimal discomfort. All mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, which is approved by the American Veterinary Association Panel on Euthanasia.

Generation of bone marrow chimeric mice

Bone marrow chimeric mice were generated by lethal irradiation (1,000 rads) of Bhlhe40+/+ or Bhlhe40−/− recipients and reconstitution with 1–2 × 107 bone marrow cells from Bhlhe40+/+ or Bhlhe40−/− donors. Mixed bone marrow chimeric mice were generated by lethal irradiation (1,000 rads) of Bhlhe40+/+ (CD45.1/.2) recipients and reconstitution with 1–2 × 107 bone marrow cells from Bhlhe40+/+ (CD45.1/.1) and either Bhlhe40+/+ (CD45.2/.2) or Bhlhe40−/− (CD45.2/.2) donors mixed at a 1:1 ratio before transfer. Mice received drinking water containing 1.3 mg sulfamethoxazole and 0.26 mg trimethoprim per ml for 2 wk after reconstitution and were allowed to reconstitute for at least 8 wk before infection with Mtb.

Cell culture

Bone marrow cells were isolated from femurs and tibias of mice and treated with ACK lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM EDTA) to lyse red blood cells. To generate M-CSF bone marrow–derived macrophages, bone marrow cells were cultured in complete IMDM (10% heat-inactivated FBS + 2 mM l-glutamine + 1× penicillin/streptomycin + 55 µM β-mercaptoethanol + 1× MEM nonessential amino acids + 1 mM sodium pyruvate) in Petri dishes with the addition of 20 ng/ml M-CSF (PeproTech). To generate GM-CSF–cultured bone marrow–derived DCs and macrophages, bone marrow cells were cultured in complete RPMI (10% heat-inactivated FBS + 2 mM l-glutamine + 1× penicillin/streptomycin + 55 µM β-mercaptoethanol) in six-well plates with the addition of 20 ng/ml GM-CSF (PeproTech). Cells were incubated at 37°C in 8% CO2 for 8–9 d. At the end of the cultures, cells were harvested, counted, and adjusted to the desired cell concentrations. For flow cytometry analysis and ELISA assays, cells were seeded at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/well in 96-well plates and were stimulated with or without 50 µg/ml heat-killed Mtb (H37Ra strain; Difco) for 18 (FACS) or 24 (ELISA) h. In some experiments, suspension cells were stimulated in the presence of 10 µg/ml heat-killed Mtb (H37Ra strain; Difco) for 4 h for ChIP assays.

To generate in vitro–polarized TH1 cells, naive splenic CD4+ T cells (Easysep mouse naive CD4+ T cell isolation kit, typical purity ∼90–96%; StemCell Technologies, Inc.) were cultured in IMDM with plate-bound anti-CD3 (2 µg/ml; clone 145-2C11; BioLegend) and anti-CD28 antibodies (2 µg/ml; clone 37.51; BioLegend) in the presence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml; BioLegend) and anti-IL-4 (20 µg/ml; Leinco). Cultures were split on day 3 and used for ChIP-seq on day 4.

For Mtb infection, cells were seeded at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells/well in 96-well plates. Mtb was washed with PBS + 0.05% Tween-80, sonicated to disperse clumps, diluted in antibiotic-free cell culture media, and added to cells at a multiplicity of infection of 1. After 4 h of incubation, cells were pelleted and washed twice with PBS, fresh culture media was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. In some cases, cells were pretreated with 250 U IFN-γ (BioLegend) for 12 h before infection. CFUs were enumerated by pelleting cells, removing supernatant, lysing with PBS + 0.5% Triton X-100, and plating serial dilutions on 7H11 agar. Colonies were counted after 3 wk of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Mtb infection of mice

Mtb cultures in logarithmic growth phase (OD600 = 0.5–0.8) were washed with PBS + 0.05% Tween-80, sonicated to disperse clumps, and diluted in sterile water. Mice were exposed to 1.6 × 108 Mtb CFUs, a dose chosen to deliver 100–200 CFUs of aerosolized Mtb per lung using an Inhalation Exposure System (Glas-Col). Within the first 24 h of each infection, lungs were harvested from at least two control mice, homogenized, and plated on 7H11 agar to determine the input CFU dose. The mean dose determined at this time point was assumed to be representative of the dose received by all other mice infected simultaneously. At each time point after infection, Mtb titers were determined by homogenizing the superior, middle, and inferior lobes of the lung or the entire spleen and plating serial dilutions on 7H11 agar. Colonies were counted after 3 wk of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2.

L. monocytogenes infection of mice

LM-Ova was diluted into pyrogen-free saline for i.v. injection into mice. For experiments involving secondary infection, some mice were initially infected with a sublethal dose of 104 LM-Ova i.v. and rested for 30 d before secondary challenge with 106 LM-Ova i.v. After 3 d, spleens and livers were homogenized separately in PBS + 0.05% Triton X-100. Homogenates were plated on brain–heart infusion agar, and L. monocytogenes CFUs were determined after growth at 37°C overnight.

Flow cytometry

Lungs were perfused with sterile PBS before harvest. Lungs and lymph nodes were digested at 37°C with 630 µg/ml collagenase D (Roche) and 75 U/ml DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich). All antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:200. Single-cell suspensions were preincubated with anti-CD16/CD32 Fc Block antibody (BD) in PBS + 2% heat-inactivated FBS for 10 min at RT before surface staining. The following anti–mouse antibodies were obtained from BioLegend: PE-Cy7 anti-CD4 (RM4-5), APC-Cy7 anti-CD8α (53–6.7), APC anti-CD11b (M1/70), BV605 anti-CD11c (N418), BV605 anti-CD19 (6D5), APC anti-CD45.2 (104), FITC anti-CD90.1 (Thy-1.1; OX-7), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD103 (2E7), Pacific blue (PB) or PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-Ly6C (HK1.4), PE anti-Ly6G (1A8), PB anti-TCRβ (H57-597), and APC anti-TCR γδ (GL3). The following anti–mouse antibodies were purchased from BD: PB anti-CD3ε (145-2C11), BV510 anti-CD45 (30F11), and PE anti–Siglec F (E50-2440). The following anti–mouse antibodies were obtained from Tonbo Biosciences: redFluor710 anti-CD44 (IM7), V450 or PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD45.1 (A20), PE-Cy7 anti-Ly6G (1A8), and redFluor710 anti-I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2).

Cells were stained for 20 min at 4°C, washed, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS for 20 min at 4°C. Cell counts were determined by hemocytometer.

For identification of antigen-specific T cells, APC-conjugated tetramers of Ag85B280–294 peptide (FQDAYNAAGGHNAVF) or ESAT64–17 peptide (QQWNFAGIEAAASA) bound to MHC-III-A(b) (National Institutes of Health Tetramer Core) were added to digested cells at final dilutions of 1:25 or 1:100, depending on the age of the tetramer stock, and incubated at RT for 75 min. Cells were then surface stained as above. Antigen-specific cells were defined as CD45+/CD3ε+/CD4+/CD44+/tetramer+.

Flow cytometry data were acquired on an LSR Fortessa cytometer (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar). Gating strategies are depicted in Fig. S5 (C and D). Gates for Tg (Bhlhe40GFP and 10BiT) mice were set using nontransgenic mice to control for background staining.

Neutrophil depletion

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 200 µg monoclonal anti-Ly6G antibody (clone 1A8; BioXCell or Leinco) or 200 µg polyclonal rat serum IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in sterile PBS (HyClone) every 48 h beginning at 10 dpi and ending at 30 dpi.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Lung samples were lysed by bead-beating in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), pelleted to remove beads, and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. RNA was purified from TRIzol using the Direct-zol RNA miniprep kit (Zymo Research) and immediately reverse transcribed with SuperScript III reverse transcription using OligodT primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using iTAQ SYBR green (Bio-Rad Laboratories) on a C1000 thermal cycler with the CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Transcript levels were analyzed using the 2ΔΔCt method normalized to Actb (β-actin) as the reference gene. The following primers were used: Actb forward, 5′-ACCTTCTACAATGAGCTGCG-3′; Actb reverse, 5′-CTGGATGGCTACGTACATGG-3′; Ccl3 forward, 5′-ACACTCTGCAACCAAGTCTTC-3′; Ccl3 reverse, 5′-AGGAAAATGACACCTGGCTG-3′; Ccl4 forward, 5′-CTGTTTCTCTTACACCTCCCG-3′; Ccl4 reverse, 5′-TGTCTGCCTCTTTTGGTCAG-3′; Ifng forward, 5′-CCTAGCTCTGAGACAATGAACG-3′; Ifng reverse, 5′-TTCCACATCTATGCCACTTGAG-3′; Il10 forward, 5′-AGCCTTATCGGAAATGATCCAGT-3′; Il10 reverse, 5′-GGCCTTGTAGACACCTTGGT-3′; Il12b forward 5′-ACTCCCCATTCCTACTTCTCC-3′; and Il12b reverse, 5′-CATTCCCGCCTTTGCATTG-3′.

Western blots

Bone marrow–derived cells were counted and lysed at 106/40 µl in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories) containing 2.5% β-mercaptoethanol. Cell lysates were loaded and separated by 12% SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and transferred to BioBlot–polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Costar). Blots were incubated with anti-Bhlhe40 (1:1,000; NB100-1800, Lot A; Novus Biologicals) or anti-HDAC1 (1:2,000; Abcam) primary antibodies at 4°C overnight with shaking. Blots were washed four to five times before incubation with anti–rabbit IgG-HRP (clone 5A6-1D10 [light chain specific]; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) at RT for 60 min with shaking. After five washes, Clarity Western ECL substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was applied, and blots were placed on blue basic autoradiography film (GeneMate). Film was developed with a medical film processor (model SRX-101A; Konica Minolta).

Cytokine ELISAs

IL-10 ELISA assays were performed on Nunc Maxisorp plates using IL-10 ELISPOT antibody pairs (BD). The enzyme reaction was developed with streptavidin-HRP (BioLegend) and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (BioLegend). Recombinant mouse IL-10 (BioLegend) was used to generate the standard curve.

Histology

Lung samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with H&E or Ziehl-Neelsen stain to identify acid-fast bacilli.

ChIP-seq

Anti-Bhlhe40 ChIP was modified from the protocol published by Chou et al. (2016). GM-CSF–cultured cells were harvested after 9 d and stimulated with 10 µg/ml heat-killed Mtb (strain H37Ra; Difco) for 4 h. In vitro–polarized TH1 cells were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/ml; Enzo Life Sciences) and ionomycin (1 µM; Enzo Life Sciences) for 1.5 h. Stimulated cells were fixed for 10 min at RT with 1% paraformaldehyde with shaking. Cross-linked chromatin was fragmented by sonication and then immunoprecipitated with polyclonal rabbit anti-Bhlhe40 antibody (NB100-1800, Lot A or Lot C1; Novus Biologicals). After immunoprecipitation, DNA was purified by the GenElute PCR cleanup kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Purified DNA was used for library construction followed by single-read sequencing on a HiSeq3000 system (Illumina) at the Genome Technology Access Center at Washington University in St. Louis. Read lengths were 101 bp and 50 bp in the case of GM-CSF–cultured bone marrow cells and TH1 cells, respectively. Fastq files were provided by the Genome Technology Access Center sequencing facility. Quality control of fastq files was performed using FastQC (0.11.3). Raw reads were mapped on the mm10 mouse reference genome using Bowtie (1.1.1). Bhlhe40−/− samples were used as input samples for peak calling on Bhlhe40+/+ samples. Peak calling was performed using MACS v1.4 (Zhang et al., 2008) with the following flags: macs14-t WT-cKO-f BAM-g mm-n WTvsKO-p 0.00001.

BEDtools (2.6; bedClip and bedGraphToBigWig) were used to visualize raw alignments. Normalized tracks were built using Deeptools (2.5.3). The UCSC Genome Browser was used for visualization. R package ChIPseeker (1.14.1) was used for peak annotation. Multiple EM for Motif Elicitation (MEME)-ChIP (4.12.0; Machanick and Bailey, 2011) was used for motif enrichment analysis using all acquired peaks. Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (GREAT; 3.0.0) was used to predict the function of cis-regulatory regions for Gene Ontology Biological Process and MSigDB Pathway gene sets (McLean et al., 2010).

Links for raw sequencing data are available at GSE113054. All primary processed data (including mapped reads) for ChIP-seq experiments are also available there.

Analysis of human expression microarrays

We used the GEO2R web tool (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r) to query the expression of genes in three publically available GEO datasets (GSE19491 [Berry et al., 2010], GSE28623 [Maertzdorf et al., 2011], and GSE42834 [Bloom et al., 2013]) that compared the whole-blood transcriptomes of humans with active TB to other humans with either no disease, latent TB, or in some cases, lung cancer, pneumonia, or sarcoidosis. The following probesets were used to examine the expression of BHLHE40 (previously called BHLHB2): for GSE19491 and GSE42834, ILMN_1768534; and for GSE28623, Agilent Technologies feature number 37383. The following probesets were used to examine the expression of STAT1: for GSE19491 and GSE42834, ILMN_1690105, ILMN_1691364, and ILMN_1777325; and for GSE28623, Agilent Technologies feature numbers 1928, 4610, 4763, 15819, 24587, 29771, 37967, and 42344. For analysis of GSE19491, the training and test sets, both encompassing samples from the United Kingdom, were combined, and the validation set containing samples from South Africa was analyzed separately. GSE28623 contained samples from The Gambia. For analysis of GSE42834, the training, test, and validation sets encompassing samples from the United Kingdom and France were combined.

Data and statistics

All data are from at least two independent experiments unless otherwise indicated. Samples represent biological (not technical) replicates of mice randomly sorted into each experimental group. No blinding was performed during animal experiments. Mice were excluded only when pathology unrelated to Mtb infection was present (i.e., weight loss caused by malocclusion or cage flooding). Statistical differences were calculated using Prism (7.0; GraphPad Software) using log-rank Mantel-Cox tests (survival), unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests (to compare two groups with normal distributions), unpaired two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests (to compare two groups with nonnormal distributions), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (to compare more than two groups with normal distributions), or unpaired Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn’s multiple comparisons tests (to compare more than two groups with nonnormal distributions). Normality was determined using a D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Sample sizes were sufficient to detect differences as small as 10% using the statistical methods described. When used, center values and error bars represent means ± SEM.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 provides additional data on pulmonary histology, hematopoietic cell population numbers, Mtb-specific T cell frequencies, the number and MFI of Mtb+ lung cells, and analysis of neutrophil-depleted mice. Fig. S2 contains in vivo expression patterns of Bhlhe40 before and after Mtb infection. Fig. S3 provides additional analysis of Mtb-infected Rag1−/−Bhlhe40−/−, Bhlhe40fl/fl Lysm-Cre, Bhlhe40fl/fl Mrp8-Cre, and mixed bone marrow chimeric mice. Fig. S4 shows representative flow cytometry plots and absolute cell counts for lung immune cells from 10BiT IL-10 reporter mice. Fig. S5 shows that Bhlhe40−/− GM-CSF–cultured cells are not defective in control of Mtb infection, putative Bhlhe40 binding sites in the Ifng locus, and the flow cytometry gating strategies used throughout this study. Data on Bhlhe40 binding sites identified by ChIP-seq, predicted functions of associated cis-regulatory regions, and associated gene ontogeny analysis in GM-CSF–cultured cells and TH1-polarized T cells are available in Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

Acknowledgments

C.L. Stallings is supported by an Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation Beckman Young Investigator Award and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease award. B.T. Edelson was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 AI113118 and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists. J.P. Huynh was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1143954). C.-C. Lin was supported by the McDonnell International Scholars Academy at Washington University in St. Louis. J.M. Kimmey was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1143954) and the National Institute of Medical General Sciences Cell and Molecular Biology Training grant GM007067. N.N. Jarjour was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 5T32AI007163. The Bhlhe40GFP mouse strain used, STOCK Tg(Bhlhe40-EGFP)PX84Gsat/Mmucd, identification number 034730-UCD, was obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center, a National Center for Research Resources–National Institutes of Health–funded strain repository, and was donated to the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–funded Gene Expression Nervous System Atlas BAC transgenic project (The GENSAT Project; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke contract N01NS02331 to the Rockefeller University). Research reported in this publication was supported by the Washington University in St. Louis Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR000448).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: J.P. Huynh, C.-C. Lin, B.T. Edelson, and C.L. Stallings designed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. J.P. Huynh and J.M. Kimmey performed Mtb infections. J.P. Huynh and C.-C. Lin performed flow cytometry. E.A. Schwarzkopf and T.R. Bradstreet performed L. monocytogenes infections. C.-C. Lin, E.A. Schwarzkopf, T.R. Bradstreet, and N.N. Jarjour generated bone marrow chimeras. E.A. Schwarzkopf performed ELISA. N.N. Jarjour performed Western blots. C.-C. Lin and T.R. Bradstreet performed ChIP experiments. I. Shchukina, O. Shpynov, and M.N. Artyomov analyzed ChIP-seq data. C.T. Weaver and R. Taneja provided key mouse strains.

References

- Abram C.L., Roberge G.L., Hu Y., and Lowell C.A.. 2014. Comparative analysis of the efficiency and specificity of myeloid-Cre deleting strains using ROSA-EYFP reporter mice. J. Immunol. Methods. 408:89–100. 10.1016/j.jim.2014.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida A.S., Lago P.M., Boechat N., Huard R.C., Lazzarini L.C.O., Santos A.R., Nociari M., Zhu H., Perez-Sweeney B.M., Bang H., et al. 2009. Tuberculosis is associated with a down-modulatory lung immune response that impairs Th1-type immunity. J. Immunol. 183:718–731. 10.4049/jimmunol.0801212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber D.L., Mayer-Barber K.D., Feng C.G., Sharpe A.H., and Sher A.. 2011. CD4 T cells promote rather than control tuberculosis in the absence of PD-1-mediated inhibition. J. Immunol. 186:1598–1607. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P.F., Lu S., Abrams J.S., Wang E., Yamamura M., and Modlin R.L.. 1993. Cytokine production at the site of disease in human tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 61:3482–3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beamer G.L., Flaherty D.K., Assogba B.D., Stromberg P., Gonzalez-Juarrero M., de Waal Malefyt R., Vesosky B., and Turner J.. 2008. Interleukin-10 promotes Mycobacterium tuberculosis disease progression in CBA/J mice. J. Immunol. 181:5545–5550. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M.P.R., Graham C.M., McNab F.W., Xu Z., Bloch S.A.A., Oni T., Wilkinson K.A., Banchereau R., Skinner J., Wilkinson R.J., et al. 2010. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature. 466:973–977. 10.1038/nature09247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom C.I., Graham C.M., Berry M.P.R., Rozakeas F., Redford P.S., Wang Y., Xu Z., Wilkinson K.A., Wilkinson R.J., Kendrick Y., et al. 2013. Transcriptional blood signatures distinguish pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary sarcoidosis, pneumonias and lung cancers. PLoS One. 8:e70630 10.1371/journal.pone.0070630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonecini-Almeida M.G., Ho J.L., Boéchat N., Huard R.C., Chitale S., Doo H., Geng J., Rego L., Lazzarini L.C.O., Kritski A.L., et al. 2004. Down-modulation of lung immune responses by interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and analysis of TGF-β receptors I and II in active tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 72:2628–2634. 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2628-2634.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante J., Boisson-Dupuis S., Abel L., and Casanova J.L.. 2014. Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease: genetic, immunological, and clinical features of inborn errors of IFN-γ immunity. Semin. Immunol. 26:454–470. 10.1016/j.smim.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C., Verbaro D.J., Tonc E., Holmgren M., Cella M., Colonna M., Bhattacharya D., and Egawa T.. 2016. The Transcription Factor AP4 Mediates Resolution of Chronic Viral Infection through Amplification of Germinal Center B Cell Responses. Immunity. 45:570–582. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A.M., Dalton D.K., Stewart T.A., Griffin J.P., Russell D.G., and Orme I.M.. 1993. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J. Exp. Med. 178:2243–2247. 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demangel C., Bertolino P., and Britton W.J.. 2002. Autocrine IL-10 impairs dendritic cell (DC)-derived immune responses to mycobacterial infection by suppressing DC trafficking to draining lymph nodes and local IL-12 production. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:994–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal Malefyt R., Abrams J., Bennett B., Figdor C.G., and de Vries J.E.. 1991. Interleukin 10(IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 174:1209–1220. 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C.G., Kullberg M.C., Jankovic D., Cheever A.W., Caspar P., Coffman R.L., and Sher A.. 2002. Transgenic mice expressing human interleukin-10 in the antigen-presenting cell compartment show increased susceptibility to infection with Mycobacterium avium associated with decreased macrophage effector function and apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 70:6672–6679. 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6672-6679.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J.L., Chan J., Triebold K.J., Dalton D.K., Stewart T.A., and Bloom B.R.. 1993. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 178:2249–2254. 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabryšová L., Howes A., Saraiva M., and O’Garra A.. 2014. The regulation of IL-10 expression. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 380:157–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzinelli R.T., Oswald I.P., James S.L., and Sher A.. 1992. IL-10 inhibits parasite killing and nitrogen oxide production by IFN-gamma-activated macrophages. J. Immunol. 148:1792–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helft J., Böttcher J., Chakravarty P., Zelenay S., Huotari J., Schraml B.U., Goubau D., and Reis e Sousa C.. 2015. GM-CSF Mouse Bone Marrow Cultures Comprise a Heterogeneous Population of CD11c(+)MHCII(+) Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. Immunity. 42:1197–1211. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng T.S.P., and Painter M.W.. Immunological Genome Project Consortium . 2008. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat. Immunol. 9:1091–1094. 10.1038/ni1008-1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölscher C., Atkinson R.A., Arendse B., Brown N., Myburgh E., Alber G., and Brombacher F.. 2001. A protective and agonistic function of IL-12p40 in mycobacterial infection. J. Immunol. 167:6957–6966. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörber S., Hildebrand D.G., Lieb W.S., Lorscheid S., Hailfinger S., Schulze-Osthoff K., and Essmann F.. 2016. The atypical inhibitor of NF-κB, IκBζ, controls macrophage interleukin-10 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 291:12851–12861. 10.1074/jbc.M116.718825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard R.C., Chitale S., Leung M., Lazzarini L.C.O., Zhu H., Shashkina E., Laal S., Conde M.B., Kritski A.L., Belisle J.T., et al. 2003. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex-restricted gene cfp32 encodes an expressed protein that is detectable in tuberculosis patients and is positively correlated with pulmonary interleukin-10. Infect. Immun. 71:6871–6883. 10.1128/IAI.71.12.6871-6883.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S.S., and Cheng G.. 2012. Role of interleukin 10 transcriptional regulation in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 32:23–63. 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i1.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E.A., and Flavell R.A.. 2005. Distal enhancer elements transcribe intergenic RNA in the IL-10 family gene cluster. J. Immunol. 175:7437–7446. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang X., Kim H.-J., Ramirez M., Salameh S., and Ma X.. 2010. The septic shock-associated IL-10 -1082 A > G polymorphism mediates allele-specific transcription via poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 in macrophages engulfing apoptotic cells. J. Immunol. 184:3718–3724. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmey J.M., Huynh J.P., Weiss L.A., Park S., Kambal A., Debnath J., Virgin H.W., and Stallings C.L.. 2015. Unique role for ATG5 in neutrophil-mediated immunopathology during M. tuberculosis infection. Nature. 528:565–569. 10.1038/nature16451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopf M., Schneider C., and Nobs S.P.. 2015. The development and function of lung-resident macrophages and dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 16:36–44. 10.1038/ni.3052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausgruber T., Blazek K., Smallie T., Alzabin S., Lockstone H., Sahgal N., Hussell T., Feldmann M., and Udalova I.A.. 2011. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1-TH17 responses. Nat. Immunol. 12:231–238. 10.1038/ni.1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-C., Bradstreet T.R., Schwarzkopf E.A., Sim J., Carrero J.A., Chou C., Cook L.E., Egawa T., Taneja R., Murphy T.L., et al. 2014. Bhlhe40 controls cytokine production by T cells and is essential for pathogenicity in autoimmune neuroinflammation. Nat. Commun. 5:3551 10.1038/ncomms4551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-C., Bradstreet T.R., Schwarzkopf E.A., Jarjour N.N., Chou C., Archambault A.S., Sim J., Zinselmeyer B.H., Carrero J.A., Wu G.F., et al. 2016. IL-1-induced Bhlhe40 identifies pathogenic T helper cells in a model of autoimmune neuroinflammation. J. Exp. Med. 213:251–271. 10.1084/jem.20150568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machanick P., and Bailey T.L.. 2011. MEME-ChIP: motif analysis of large DNA datasets. Bioinformatics. 27:1696–1697. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking J.D., Taylor G.A., and McKinney J.D.. 2003. Immune control of tuberculosis by IFN-γ-inducible LRG-47. Science. 302:654–659. 10.1126/science.1088063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertzdorf J., Ota M., Repsilber D., Mollenkopf H.J., Weiner J., Hill P.C., and Kaufmann S.H.E.. 2011. Functional correlations of pathogenesis-driven gene expression signatures in tuberculosis. PLoS One. 6:e26938 10.1371/journal.pone.0026938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Llordella M., Esensten J.H., Bailey-Bucktrout S.L., Lipsky R.H., Marini A., Chen J., Mughal M., Mattson M.P., Taub D.D., and Bluestone J.A.. 2013. CD28-inducible transcription factor DEC1 is required for efficient autoreactive CD4+ T cell response. J. Exp. Med. 210:1603–1619. 10.1084/jem.20122387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard C.L., Harrington L.E., Janowski K.M., Oliver J.R., Zindl C.L., Rudensky A.Y., and Weaver C.T.. 2007. Regulatory T cells expressing interleukin 10 develop from Foxp3+ and Foxp3- precursor cells in the absence of interleukin 10. Nat. Immunol. 8:931–941. 10.1038/ni1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean C.Y., Bristor D., Hiller M., Clarke S.L., Schaar B.T., Lowe C.B., Wenger A.M., and Bejerano G.. 2010. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol. 28:495–501. 10.1038/nbt.1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira-Teixeira L., Redford P.S., Stavropoulos E., Ghilardi N., Maynard C.L., Weaver C.T., Freitas do Rosário A.P., Wu X., Langhorne J., and O’Garra A.. 2017. T Cell-Derived IL-10 Impairs Host Resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. J. Immunol. 199:613–623. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray P.J., Wang L., Onufryk C., Tepper R.I., and Young R.A.. 1997. T cell-derived IL-10 antagonizes macrophage function in mycobacterial infection. J. Immunol. 158:315–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi B., and Behar S.M.. 2011. Regulation of neutrophils by interferon-γ limits lung inflammation during tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 208:2251–2262. 10.1084/jem.20110919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olobo J.O., Geletu M., Demissie A., Eguale T., Hiwot K., Aderaye G., and Britton S.. 2001. Circulating TNF-α, TGF-β, and IL-10 in tuberculosis patients and healthy contacts. Scand. J. Immunol. 53:85–91. 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00844.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow J.R., Tan Y.H., Jin Y., Bahirvani A.G., and Taneja R.. 2014. Stra13 and Sharp-1, the non-grouchy regulators of development and disease. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 110:317–338. 10.1016/B978-0-12-405943-6.00009-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon G.F.T., Dong Y., Marshall K.C., Arif A., Deeg C.M., Dosanjh M., and Johnson P.. 2015. Hyaluronan Binding Identifies a Functionally Distinct Alveolar Macrophage-like Population in Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cell Cultures. J. Immunol. 195:632–642. 10.4049/jimmunol.1402506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]