Abstract

Prophages are known to encode important virulence factors in the human pathogen Vibrio cholerae. However, little is known about the occurrence and composition of prophage-encoded traits in environmental vibrios. A database of 5,674 prophage-like elements constructed from 1,874 Vibrio genome sequences, covering sixty-four species, revealed that prophage-like elements encoding possible properties such as virulence and antibiotic resistance are widely distributed among environmental vibrios, including strains classified as non-pathogenic. Moreover, we found that 45% of Vibrio species harbored a complete prophage-like element belonging to the Inoviridae family, which encode the zonula occludens toxin (Zot) previously described in the V. cholerae. Interestingly, these zot-encoding prophages were found in a variety of Vibrio strains covering both clinical and marine isolates, including strains from deep sea hydrothermal vents and deep subseafloor sediments. In addition, the observation that a spacer from the CRISPR locus in the marine fish pathogen V. anguillarum strain PF7 had 95% sequence identity with a zot gene from the Inoviridae prophage found in V. anguillarum strain PF4, suggests acquired resistance to inoviruses in this species. Altogether, our results contribute to the understanding of the role of prophages as drivers of evolution and virulence in the marine Vibrio bacteria.

Introduction

The Vibrio genus (vibrios) is a genetically and metabolically diverse group of heterotrophic bacteria that are ubiquitously distributed in the oceans and often accounts for a large fraction (0.5–5%) of the total bacterial community, occasionally developing massive blooms1,2. The group includes several human pathogens (e.g., V. cholerae and V. parahaemolyticus)3, and pathogens infecting corals (V. coralliilyticus) and fish (e.g., V. anguillarum, V. harveyi)4,5. Virulence-related factors in these pathogens are often associated with mobile genetic elements (e.g., prophages and genomic islands)6,7, suggesting that horizontal acquisition of these elements is required for the development of virulence in vibrios. A well-known example of prophage-associated virulence is in V. cholerae8 where the key toxins (CTX and Zonula occludens toxin (zot)) are prophage encoded. The zot gene was first detected in V. cholerae and is encoded by the CTXφ prophage9. Besides its role as a cytotoxin, Zot appears to be structurally and functionally related to CTX phage assembly, suggesting that this protein may have a dual function10.

Prophage-associated toxins have also been identified in the marine vibrios such as: V. coralliilyticus11 and V. anguillarum7 and V. parahaemolyticus12, indicating that prophage-encoded virulence genes are disseminated among environmental Vibrio populations. Recently, a zot-encoding prophage was detected in three fish pathogenicV. anguillarum strains7. The Zot-like protein contained an N-terminus involved in phage assembly, and C-terminal, which is cleaved and secreted into intestinal lumen where it increases intestinal epithelial permeability by affecting the tight junctions9. Similarly, prophage genomes encoding toxin genes with homology to those found in pathogenic V. cholerae were found in V. coralliilyticus genomes11. Also, experimental evidence of efficient prophage-mediated transfer of virulence between strains of the fish pathogen V. harveyi12 emphasizes that prophage-encoded virulence is a dynamic property of environmental vibrios. Together, these studies strongly suggest that prophages in Vibrio bacteria harbor multiple and diverse genetic elements with large effects on pathogenicity and host fitness and a large potential for dissemination among the Vibrio group. Thus, the emergence of environmental Vibrio bacteria with significant virulence traits constitutes a direct concern for human public health, food, and the aquaculture industry. While the ability of prophages to impact the pathogenicity of V. cholerae is well studied8,13, little is known about the distribution and role of prophage-encoded fitness factors in a broader range of environmental Vibrio bacteria. We are therefore only beginning to comprehend the extent of prophage influence on microbial performance, gene exchange and evolution in the Vibrio group, and the potential of prophage genes as a reservoir of transmissible virulence factors among vibrios in marine environments.

The aim of this study was to explore the potential role of prophages for the dissemination of virulence and other niche adaptation factors in environmental marine vibrios. By mapping and characterization of prophage-like elements and their distribution in the ~2000 available whole genome sequenced Vibrio strains, we demonstrate that prophage-encoded functional properties such as virulence and antibiotic resistance are widely distributed among environmental vibrios. Hence, Vibrio prophages and temperate phages are potentially key driving forces in niche adaptation, dissemination of virulence and emergence of disease in environmental marine Vibrio communities.

Results

General features of Vibrio prophage-like elements database

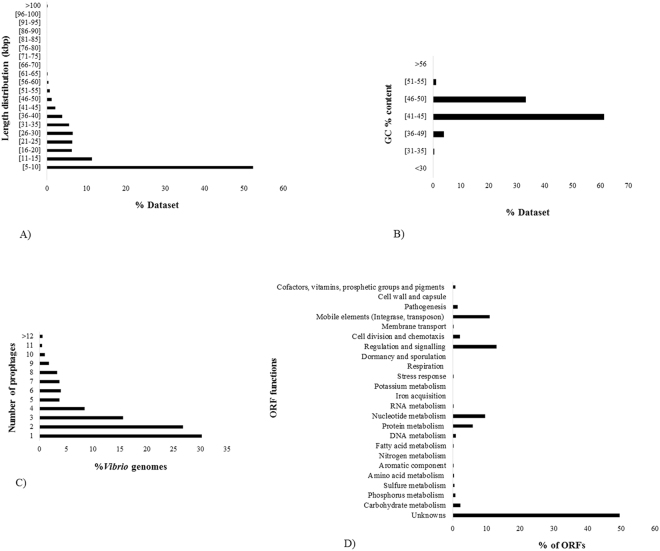

Among the 1,874 sequenced Vibrio genomes available in NCBI database (Table S1), we identified the occurrence, composition and distribution of 5,674 prophage-like elements (>108 bp; >90,000 ORFs) representing the largest collection of prophage-like elements in Vibrio bacteria so far. Since the available genome sequences of Vibrio temperate phages in NCBI database were all >5 kb, we restricted our search to prophage-like elements larger than 5 kb. In general, prophage sequence length and GC content ranged from 5 to 126 kb and 31.7 to 54.9%, respectively. Most of these prophage-like elements had a GC content between 41 and 45% (60%) and a size range of 5–10 kb (54%), corresponding to the smallest sized inovirus prophage sequence available in the NCBI database (Fig. 1A,B; See Supplementary Table S1). Among the 1,874 Vibrio genomes, 69.5% were poly-lysogenic, containing >1 prophage sequence (Fig. 1C). Functional analysis of annotated prophage-like elements showed that 49.6% of ORFs were hypothetical proteins without function assigned, while the remaining ORFs represented mostly mobile elements (eg., integrases, tranposases), nucleotide and protein metabolism, regulation and signaling (Fig. 1D). Finally, the completeness of the prophage-like elements was estimated by PHASTER, resulting in 36% intact, 56% incomplete and 8% questionable.

Figure 1.

Prophage-like element features among Vibrio genomes sequences used in this study. (A) length distribution of Vibrio prophage-like elements. (B) GC% content in Vibrio prophage-like elements. (C) Distribution of number of prophages per Vibrio genome. (D) Percentage of annotated functions of ORFs in prophage-like elements (analyzed by SEED Subsystems).

Vibrio prophage-like elements encoded potential host fitness factors

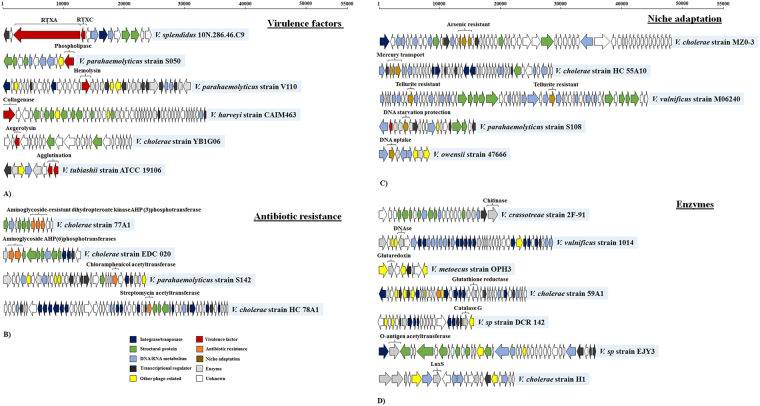

In order to assess the potential influence of prophages on host functional properties, we mapped the distribution of key genes could be related to virulence factor production, antibiotic resistance, niche adaptation factors, metabolism and enzymes, according to the annotation pipeline showed by MG-RAST (See Supplementary Table S2). We found that 19.5% (n = 1,109) of the prophage-like elements encoded a potentially important gene for the host. For example, virulence factors such as RTX toxins (n = 100), collagenases (n = 5), lipases (n = 10), agglutination (n = 30), hemolysin (n = 4) and aerolysin (n = 1) were found in prophage like elements belonging to V. parahaemolyticus, V. cholerae, V. harveyi, V. splendidus, V. tasmaniensis, V. tubiashii and V. hepatarius (Fig. 2A; See Supplementary Table S2). Genes related to antibiotic resistance (total n = 116) (kanamycin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin among others) were found mostly in prophage like-elements in V. cholerae and V. parahaemolyticus. We identified genes encoding APH(3″)/APH(6″) family aminoglycoside O-phosphotransferases (n = 3), type B chloramphenicol O-acetyltransferase (n = 23) and streptomycin 3′-adenylyltransferase (n = 5) (Fig. 2B; See Supplementary Table S2). Prophages containing niche adaptation factors with high similarity to heavy metal resistance (n = 32) and natural DNA uptake transformation (n = 3) genes were also found (Table S2). For example, V. cholerae strains had prophage-like elements encoding genes involved in resistance to arsenic and mercury, while V. vulnificus harbored a prophage which encoded genes related to tellurite resistance (Fig. 2C; See Supplementary Table S2). V. anguillarum and V. parahaemolyticus had prophages encoding the dps gene, which is related to DNA protection under starvation conditions (Fig. 2C; See Supplementary Table S2). Finally, V. crassostreae, V. owensii and V. caribbeanicus had prophages that encoded dprA gene, which has been linked to natural DNA uptake in aquatic environments (Fig. 2C; See Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2.

Genomic organization of prophage-like elements detected in Vibrio genomes carrying genes potentially beneficial for the host. (A) Prophage-like elements carrying virulence factor genes. (B) Prophage-like elements carrying antibiotic resistance genes. (C) Prophage-like elements carrying niche adaptation genes. (D) Prophage-like elements carrying enzyme genes. Arrows represent the predicted ORFs and point in the direction of transcription. The colors were assigned according to the possible role of each ORF as is shown in the figure. The representative phages displayed in this figure have been classified as complete or questionable prophages (See Supplementary Table S2).

Besides the mentioned fitness factors, a sub-classification of enzymes was encoded by a number of Vibrio prophages. Chitinases (n = 6) were found mostly in prophage-like elements in V. crassostreae and V. parahaemolyticus (Fig. 2D). The presence of tatD gene (n = 11), which possesses DNAse activity, was found in pathogenic species including V. vulnificus, V parahaemolyticus and V. cholerae (Fig. 2D; Table S2). Also, we found redox enzymes such as glutaredoxin (n = 54) and glutathione reductase (n = 19), which were widely distributed in V. metoecus, V. cholerae, V. harveyi, V. navarrensis and V. alginolyticus (Fig. 2D; See Supplementary Table S2). Contrarily, catalase KatG (n = 1) was found only in V. sp (Fig. 2D). Finally, gene oafA (n = 11), which encodes a peptidoglycan/LPS-O-acetylase, was found in prophages of V. alginolyticus, V. harveyi and V. sp (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, we found a prophage-like element in V. cholerae encoding luxS gene (n = 1), which is involved in the synthesis of the quorum sensing molecule AI-2 (Fig. 2D; See Supplementary Table S2).

Distribution of Zot-like toxin in Vibrio genomes

The zonula occludens toxin gene (zot) located on CTX prophage is associated with the pathogenicity of V. cholerae9. In order to examine whether zot- encoding prophages are more widely distributed in Vibrio species beyond V. cholerae, we examined the frequency of zot-encoding prophages in the entire database and determined the phylogenetic relationship of the Zot toxin amino acid sequence. In addition to 314 Zot toxins found in the CTX prophages of V. cholerae, we found 501 zot-encoding prophages in twenty-eight out of sixty-four Vibrio species (14.5% of prophage-like elements database) (See Supplementary Table S1). For these prophages, the %GC ranged from 39.5 to 47.5 and the length from 5–12 kb.

The zot-encoding prophages were found in the majority of the clinical isolates of V. cholerae (56.3%) and V. parahaemolyticus (77.9%) (See Supplementary Table S1). However, we also found this specific prophage in Vibrio species that were not associated with clinical samples or disease outbreaks (Table S1). Overall, 15.2% of environmental marine Vibrio isolates contained a zot-encoding prophage, including isolates from coastal marine waters (e.g. V. campbellii), deep hydrothermal vents (e.g. V. antiquarius and V. diabolicus) and deep subseafloor sediments (e.g. V. diazotrophicus) (See Supplementary Table S1).

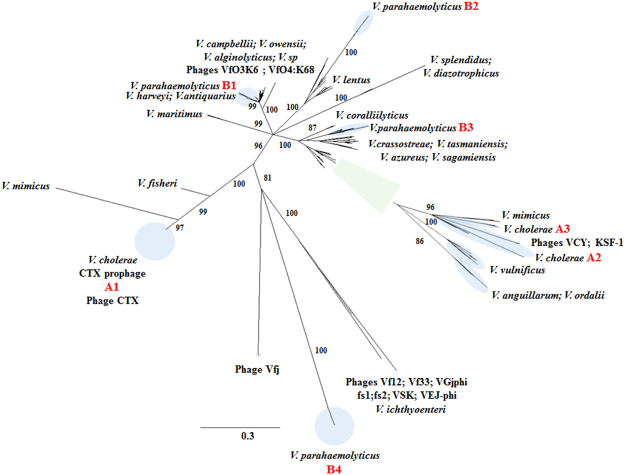

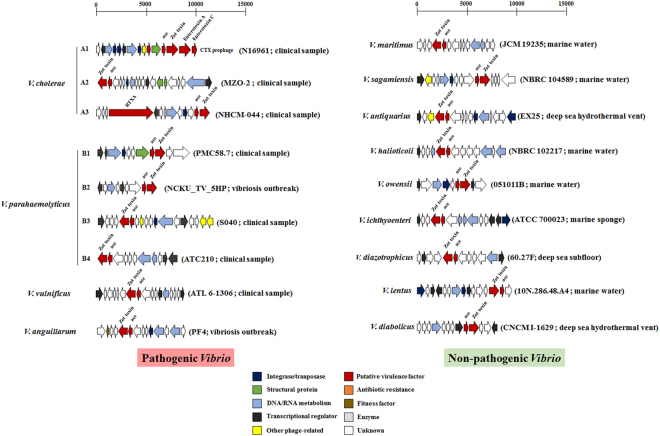

Phylogenetic analysis of Zot-like toxin proteins based on maximum likelihood algorithm showed that sequences from V. parahaemolyticus and V. cholerae clustered in subgroups (Fig. 3). V. cholerae Zot-like toxin grouped in 3 different clusters named A1, A2 and A3. The group A1 consisted of the Zot-like sequences associated with well-studied CTX prophage, whereas the diversity of A2 group differed from the CTX prophage, and A3 contained of group of prophages which had both Zot and RTXA toxins (Figs 3 and 4; Table S2). Similarly, V. parahaemolyticus displayed four different clusters of Zot-like proteins (B1–B4), where the B4 group included the zot toxin encoded by prophage O3:K6 identified in the pandemic V. parahaemolyticus clone (Figs 3 and 4). The presence of Zot-like proteins in environmental Vibrio species, which have previously been isolated as non-pathogenic strains from several marine environments, included zot-encoding prophages in V. maritimus, V. sagamiensis, V. owensii, V. diazotrophicus and V. halioticoli (Fig. 4; See Supplementary Table S1). For some Vibrio species, the different Zot-like proteins were located in the same phylogenetic group. For example, Zot-like toxins from V. campbellii, V. owensii, and V. alginolyticus grouped together as did the zot toxins in V. anguillarum and V. ordallii (Fig. 3). In other Vibrio species, the Zot proteins formed monophylogenetic groups, such as in V. vulnificus and V. coralliilyticus (Fig. 3). Another feature of this analysis is the divergent clustering of the Zot-like proteins from the documented Vibrio filamentous phages (See Supplementary Table S1). Based on the phylogenetic tree, V. parahaemolyticus phage Vf3314 appears to be more closely related to V. cholerae phages VGJ15, fs116, fs217, VSK18, VEJ19 and VFJ20 than with V. parahaemolyticus filamentous phages VfO3:K6 and VfO4:K6821, which made up a distinct branch in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3). Interestingly, all these zot-encoding prophages contained the Accessory Cholera Enterotoxin gene (ace), which has been described also in CTX prophage9 (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Phylogeny of Zot-like proteins obtained from zot-encoding prophages. Unrooted phylogenetic tree constructed from Zot-like toxin amino acid sequences, using the maximum likelihood algorithm with 1000 bootstraps. Bootstrap values <80% were removed from the tree. Circles with a blue color highlight the different phylogenetic groups described in the text (A1–A3 and B1–B4). In addition, green square is a zoom in on the specific cluster in the phylogenetic tree containing the groups A2 and A3. The horizontal bar at the base of the figure represents 0.3 substitutions per amino acid site.

Figure 4.

Genomic organization of zot-encoding prophages in Vibrio species. Diagrammatic representation of zot-encoding prophage-like elements integrated into the chromosomes of different pathogenic and non-pathogenic (environmental) Vibrio species (See Supplementary Table S1). The colors were assigned according to the possible role of each ORF as is shown in the Figure. Parentheses represent strain name and source of isolation for each example.

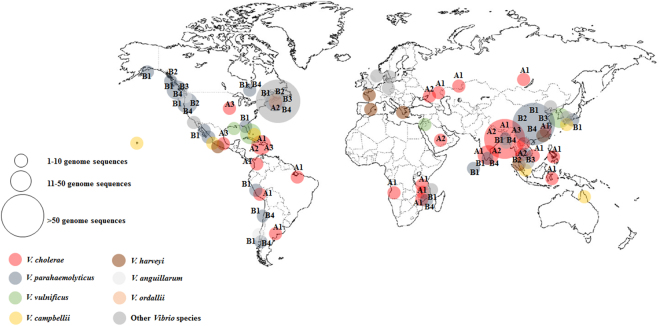

To include the geographical variability in zot-encoding prophages, we determined the spatial distribution of Vibrio sequences carrying the prophages. The analysis showed a global scale distribution of Zot-like proteins with no well-defined geographical patterns (Fig. 5). However, some phylogenetic groups were associated with specific geographic sites. For example, V. parahaemolyticus isolates carrying a Zot-like toxin isolated in India and Bangladesh were linked only to phylogenetic groups B2 and B4. Similarly, Zot-sequences belonging to the group B1 were found mostly along the Pacific coast (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Geographical distribution of zot-encoding prophages in Vibrio species. Global distribution of zot-encoding prophages in Vibrio species. Color blocks represent the Vibrio species most abundant in our database. The size of the circles is proportional to the number of Vibrio genome sequences carrying a zot-encoding prophage in a specific geographic location. Main phylogenetic groups identified for V. cholerae (A1–A3) and V. parahaemolyticus (B1–B4) were included in the figure to facilitate comparison.

CRISPR arrays in V. anguillarum

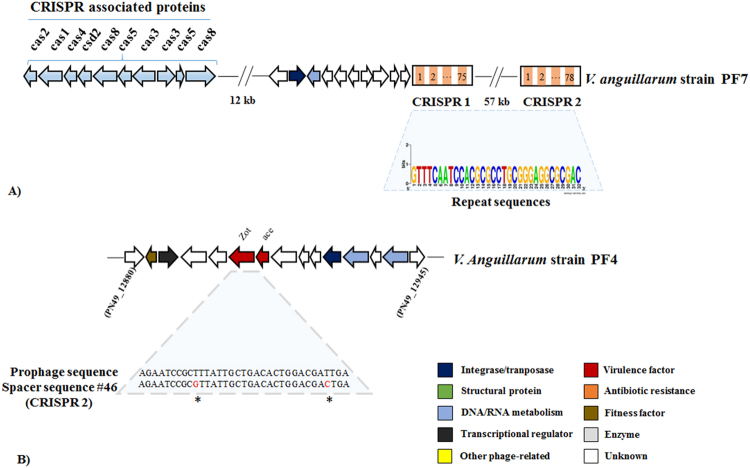

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) arrays were previously found in 11.9% of the Vibrio genome sequences. In addition, 0.03% of the genomes had more than one CRISPR array22, and the longest array found in V. anguillarum strain PF7 (Accession numbers: CP011464 and CP011465) harbored ten cas genes (type I CRISPR-cas system) with identical repeats of 32 bp and two arrays with seventy-eight and seventy-five spacers, respectively (Fig. 6A; 14). Comparing nucleotide similarity of V. anguillarum spacers from these two CRISPRs with sequences of all zot-encoding prophage-like elements in our database revealed that 1 of 153 spacers (CRISPR array 2, spacer #46) matched (95% similarity) a zot toxin gene in a potential Inoviridae prophage sequence from V. anguillarum strain PF4 (Accession numbers: CP010080 and CP010081) (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Genomic architecture of CRISPR-Cas systems in V. anguillarum strain PF7 and potential protection against inoviruses. (A) Location and genomic organization of two CRISPR arrays in V. anguillarum strain PF7. The weblogo represents the conservation of that nucleotide at each position in the repeat. (B) Genomic organization of putative Inoviridae prophage-like element in V. anguillarum strain PF4. Comparison of spacer from CRISPR 2 and zot sequence is shown. Asterisks represent point mutations between the prophage sequence and the CRISPR spacer. Arrows display the predicted ORFs and point in the direction of transcription. The colors were assigned according to the possible role of each ORF as is shown in the figure.

Discussion

Despite the well-established role of prophages as sources of virulence properties in vibrios, little is known about the abundance, genetic composition and diversity, and induction abilities of prophage-like elements in Vibrio species beyond human pathogens such as V. cholerae8,9. Exploring the Vibrio prophage database for the presence of specific genes that potentially confer virulence or niche adaptations to the host demonstrated that these properties were widely distributed in the global collection of sequenced genomes (Fig. 2; See Supplementary Table S2). Specifically, our results showed that virulence, niche adaptation and antibiotic resistance genes encoded by prophage-like elements are not restricted to human pathogens (e.g. V. cholerae and V. parahaemolyticus) but are efficiently exchanged among the Vibrio genus, and dispersed among species considered to be non-pathogenic such as V. azureus, V. hepatarius and V. diazotrophicus (Figs 2–4). One of the V. diazotrophicus isolate harboring a zot-encoding prophage originated from sediments 79.5 meter below seafloor, corresponding to an estimated sediment age between 16,000–80,000 years23,24, indicating the that these prophages have been interacting with their Vibrio hosts across long term evolutionary time scales. Moreover, 49.6% of the phage-encoded ORFs in the database were predicted to encode hypothetical proteins with unknown functions (Fig. 1D), which potentially also could carry out functions supporting host performance and adaptations25. Thus, Vibrio prophages and temperate phages may constitute a major reservoir of virulence and niche adaptation traits in marine systems. Additionally, their widespread distribution among Vibrio species suggests that the induction and integration of these phages drive the dissemination of these genes, contributing to the genetic diversification and functional adaptations of Vibrio communities26.

In addition to V. cholerae, several other Vibrio species were recently reported to contain zot-encoding prophages7,24,27. Here we found a cosmopolitan distribution of zot- encoding prophages in twenty-eight different Vibrio species such as V. vulnificus, V. maritimus, V. azureus, V. crassostreae, V. diazotrophicus and V. halioticoli (Fig. 4; See Supplementary Table S1). This is in line with the large-scale distribution of zot-encoding prophages across the world’s oceans, suggesting the interaction and co-existence of inovirus phages and Vibrio bacteria on a global scale (Fig. 5)28. Thus, our data suggest that zot-encoding prophages are widespread in Vibrio species and define a group of prophage-like elements that could undergo extensive horizontal gene transfer. This suggestion is supported by the phylogenetic analysis, where many of the Zot-like proteins from the different Vibrio species (e.g., V. owensii and V. alginolyticus; V. splendidus and V. diazotrophicus) showed high similarity, despite very different genomic organization of the prophages they originated from (Fig. 4). The fact that many variants of zot-encoding prophages are prevalent in specific species suggests that they could play a role in horizontal transfer of the zot gene, as has been reported for CTX and other filamentous phages19,21. Moreover, our results displayed a wide geographical distribution of zot-encoding prophages, suggesting also that these specific elements may have an important role in the dispersion of genes by exploring new Vibrio hosts (Fig. 5)7,24,27. Interestingly, we demonstrate that specific lineages of the Zot toxin are not exclusively associated with specific pathogenic species, again suggesting that lysogenization with this group of phages occurs across the Vibrio genus.

Lysogenic conversion of non-virulent strains into virulent ones by integration of a prophage has so far mainly been associated with the emergence of new virulent and epidemic clones of human pathogens such as V. cholerae and E. coli O157:H7 following lysogenization with phage CTXφ8 and the shiga toxin encoding phages Sp5 and Sp1529, respectively. Thus, the suggested efficient exchange and dispersal of virulence factors among environmental Vibrio species represents a novel perception of prophages as drivers of the virulence evolution and diversification of the global Vibrio communities, and supports recent evidence that virulence in the coral pathogen V. coralliilyticus is acquired by lysogenization with zot-encoding prophages10. The current observation that several Vibrio species designated as harmless environmental bacteria contained specific virulence traits acquired from induced phages from pathogenic donors, suggests that these strains act as potential biological reservoirs of these genes in the environment (Fig. 4). This idea is supported by observations in V. mimicus, which harbor CTX phage and may play a role in the emergence of new pathogenic V. cholerae30.

Presence of prophage genes obviously does not imply the functionality of the gene. Previously, experimental evidence of prophage-mediated virulence was demonstrated in environmental V. harveyi strains, which transformed into virulent forms following infection with a temperate phage12. However, prophage functionality determined by in silico predictions requires experimental validation, including induction experiments, gene expression studies and cytotoxicity evaluation, to assess the functional implications of prophage encoded properties and their dissemination in marine Vibrio communities.

The observed spacer match from the CRISPR region in V. anguillarum strain PF7 with a zot-encoding prophage in V. anguillarum strain PF4 (Fig. 6) indicated that CRISPR is used as an adaptive immunity defense against inoviruses in V. anguillarum, potentially affecting the evolution and virulence of this species31. The selection for defense mechanisms against Inoviridae infection emphasizes that the negative effects of phage inovirus infection may exceed the potential benefits from acquisition of virulence and other fitness factors. Thus, fitness cost such as replication of the additional phage DNA or interference with the fine-tuned physiology of the recipient cell32, may select against integration of inoviruses at certain conditions or in certain species.

While the present study provides a bioinformatic approach to assessing the potential importance of temperate phages for pathogenicity of Vibrio, some limitations to the analysis must be considered. First, the number of prophage-like elements likely represents a minimum estimate as the large number of phage-ORFs which are not related to known phage genes make prophages less recognizable by in silico analysis33. Second, some old Vibrio genomes were compromised by many assembly contigs (>200; See Supplementary Table S1); thus, prophage-like elements may have been split into multiple contigs and thus not detected. Finally, a high fraction of the prophage-like elements ranged from 5 to 10 kb (37.5% which were not related to zot-encoding prophages), and 56% of the sequences were incomplete prophages (Fig. 1A–D), indicating that the majority of Vibrio prophages probably have gone through mutational decay after integration and may lack the ability to lyse the cell and disseminate the phage-encoded genes to other Vibrio hosts. Despite these limitations, we consider this study as a starting point for further exploration of the ecology and evolution of Vibrio pathogens in aquatic systems. Lysogenic conversion in vibrios could represent a direct concern for human health, food safety and aquaculture industry34,35, and insight into the influence of phages as carriers of these virulence factors and as vehicles for their dispersal is essential for understanding the role of prophages as drivers of virulence in marine Vibrio communities.

Methods

Genome sequences collection

The Vibrio DNA sequences used in this study were obtained from National Center for Biotechnology Information database (NCBI) (October, 2016). A total of 1880 genomes representing sixty-four Vibrio species covered a variety of environments and wide geographic (>30,000 km) and temporal scales (>100 years) of isolation (Table S1, for genome details). We filtered out low quality assemblies which had N50 scores of <10 kbp and/or consisted of more than 400 contigs. Moreover, we included a collection of thirteen bacteriophage genome sequences belonging to the family Inoviridae. Accession numbers for each individual selected genome sequence were included in the Supplementary Table S1.

Prophage-like element database construction

Prophage-like sequences were identified and selected by running available bacterial genomes in PHASTER (PHAge Search Tool)36. Because of their small sizes (typically between 5 to10 kb), some inoviruses were detected using a manual procedure by searching for similarity to known filamentous phages (See Supplementary Table S1 for phage genome details) by BLASTP (requiring an e-value <0.001). When at least three core ORFs from inoviridae family (Relative to CTX prophage: ADE80683.1 [RstA]; AAF29545.1 [OrfU]; YP_004286238.1 [ace]) were found in a window of 5–10 kb, reannotation of putative prophage ORFs was done by performing a BLASTP search against GenBank database37. The beginning and end of a specific prophage genome was estimated based on the annotation of the surrounding genes.

Output FASTA files containing prophage nucleotide sequences were subsequently subjected to a final manual review, including information about Vibrio species, specific strain and completeness (Complete, questionable or incomplete). Assessment of the completeness of the prophage was based on three specific criteria. Firstly, the genomic similarity of phage-related genes with prophage sequences deposited in the PHASTER database. Secondly, the presence of phage-related genes in a DNA sequence should be >50% of the total ORFs. Thirdly, the presence of specific phage-related cornerstone proteins (Integrase, fiber, tail, capsid, terminase, protease and lysin), attachment sites, tRNA or short nucleotides repeats should give a score of 10 for each key gene found. Based on these criteria a score value was calculated for each prophage sequence. A specific DNA sequence was considered a complete prophage-like element when the score was above 90 (See details36). Finally, the updated files were merged into a unique local custom database using Geneious V.10.1.338. Although the current annotation was generally maintained, certain ORFs were re-analyzed using BLASTP and the annotation updated37. The Vibrio prophage-like elements database is available as MG-RAST database at library mgl583439.

Prophage-like element sequences were annotated by using MG-RAST server (version 3.3)39. The ORFs were distributed into different categories, according to similarity with protein databases.

Identification of orthologs and ecologically relevant genes in prophage-like elements

The Vibrio prophage-like element database was screened for virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, niche adaptation and metabolic genes by tblastn alignment of annotated ORFs using BLAST + v2.2.24, with default parameters (E-value 10−4, amino acid identity >30%). Also, virulence or fitness factors previously identified in the fish pathogen V. anguillarum7 and V. parahaemolyticus27 were included in this study. Specific proteins in each of the orthologous groups were manually inspected using BLAST40 and Phyre241.

Phylogenetic analyses of Zot-like proteins

To reveal the phylogenetic relationship among genes encoding the identified zonula occludens toxins (Zot), we selected the 702 zot genes from complete inovirus sequences in our prophage-like element database. Deduced Zot amino acid sequences were aligned using Clustal W version 2.042 and phylogeny was inferred using Maximum Likelihood (1,000 bootstrap replicates) in Geneious version 10.1.338.

CRISPR array identification

In V. anguillarum, CRISPR arrays had previously been identified and analyzed22. Repeat sequences were compared by WebLogo analysis, a Web-based application that generates graphical representations (logos) of the patterns within a multiple-sequence alignment43. Spacer sequences were aligned to the prophage-like elements using ClustalW42 in Geneious v.10.1.338.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Danish Council for Strategic Research (ProAqua project 12-132390) and the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF – 7014-00080) to MM, and the US National Science Foundation OCE-1435993 to MFP.

Author Contributions

M.M. and D.C. conceived the idea. D.C. performed the genomic analysis. D.C., M.M., K.F., F.H., P.K., N.R. and M.F.P. analyzed the results. D.C. and M.M. wrote the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-28326-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Takemura AF, Chien DM, Polz MF. Associations and dynamics of Vibrionaceae in the environment, from the genus to the population level. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:38. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert JA, et al. Defining seasonal marine microbial community dynamics. ISME J. 2012;6:298–308. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakraborty S, Nair GB, Shinoda S. Pathogenic vibrios in the natural aquatic environment. Rev Environ Health. 1997;12:63–80. doi: 10.1515/REVEH.1997.12.2.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Haim Y, et al. Vibrio coralliilyticus sp. nov., a temperature-dependent pathogen of the coral Pocillopora damicornis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:309–15. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pruzzo, C., Huq, A., Colwell, R. R. & Donelli, G. Pathogenic Vibrio species in marine and estuarine environment in Oceans and Health: Pathogens in the Marine Environment (eds Colwell, R. R. & Belkin, S.) 217–252 (Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, 2005).

- 6.Gennari M, Ghidini V, Caburlotto G, Lleo MM. Virulence genes and pathogenicity islands in environmental Vibrio strains nonpathogenic to humans. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;82:563–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castillo D, et al. Comparative genome analyses of Vibrio anguillarum strains reveal a link with pathogenicity traits. mSystems. 2017;2:pii: e00001–17. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00001-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science. 1996;272:1910–4. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fasano A, et al. Vibrio cholerae produces a second enterotoxin, which affects intestinal tight junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5242–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Pierro M, et al. Zonula occludens toxin structure-function analysis. Identification of the fragment biologically active on tight junctions and of the zonulin receptor binding domain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19160–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weynberg KD, Voolstra CR, Neave MJ, Buerger P, van Oppen MJ. From cholera to corals: Viruses as drivers of virulence in a major coral bacterial pathogen. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17889. doi: 10.1038/srep17889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munro J, Oakey J, Bromage E, Owens L. Experimental bacteriophage-mediated virulence in strains of Vibrio harveyi. Dis Aquat Org. 2003;54:187–194. doi: 10.3354/dao054187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner PL, Waldor MK. Bacteriophage control of bacterial virulence. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3985–93. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.3985-3993.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang B, Taniguchi H, Miyamoto H. & Yoshida, Si. Filamentous bacteriophages of Vibrio parahaemolyticus as a possible clue to genetic transmission. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5094–101. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5094-5101.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campos J, et al. VGJ phi, a novel filamentous phage of Vibrio cholerae, integrates into the same chromosomal site as CTX phi. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:5685–96. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.19.5685-5696.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehara M, et al. Characterization of filamentous phages of Vibrio cholerae O139 and O1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;154:293–301. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikema M, Honma Y. A novel filamentous phage, fs-2, of Vibrio cholerae O139. Microbiology. 1998;144:1901–6. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-7-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kar S, Ghosh RK, Ghosh AN, Ghosh A. Integration of the DNA of a novel filamentous bacteriophage VSK from Vibrio cholerae 0139 into the host chromosomal DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campos J, Martínez E, Izquierdo Y, Fando R. VEJ{phi}, a novel filamentous phage of Vibrio cholerae able to transduce the cholera toxin genes. Microbiology. 2010;156:108–15. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.032235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang. Q, Kan B, Wang R. Isolation and characterization of the new mosaic filamentous phage VFJ Φ of Vibrio cholerae. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasu H, et al. A filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2156–61. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2156-2161.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalatzis PG, et al. Stumbling across the same phage: comparative genomics of widespread temperate phages infecting the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Viruses. 2017;9:pii: E122. doi: 10.3390/v9050122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrén, T., Jørgensen, B. B. & Cotterill, C. Baltic Sea Basin Paleoenvironment: paleoenvironmental evolution of the Baltic Sea Basin through the last glacial cycle. Scientific prospectus integrated ocean drilling program expedition 347, 10.2204/iodp.sp.347.2012 (2012).

- 24.Castillo D, Vandieken V, Engelen B, Engelhardt T, Middelboe M. Draft genome sequences of six Vibrio diazotrophicus strains isolated from deep subsurface sediments of the Baltic Sea. Genome Announc. 2018;6:pii: e00081–18. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00081-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brueggemann AB, et al. Pneumococcal prophages are diverse, but not without structure or history. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42976. doi: 10.1038/srep42976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feiner R, et al. A new perspective on lysogeny: prophages as active regulatory switches of bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:641–50. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castillo D, et al. Exploring the genomic Traits of non-toxigenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated in southern Chile. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:161. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breitbart, M., Rohwer, F. & Abedon, S. T. Phage ecology and bacterial pathogenesis in Phages: their role in bacterial pathogenesis and biotechnology (eds Waldor, M. K., Friedman, D. I. & Adhya, S. L) 66–91 (ASM Press, Washington DC, 2005).

- 29.Herold S, Karch H, Schmidt H. Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages–genomes in motion. Int J Med Microbiol. 2009;294:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyd EF, Moyer KE, Shi L, Waldor MK. Infectious CTXPhi and the vibrio pathogenicity island prophage in Vibrio mimicus: evidence for recent horizontal transfer between V. mimicus and V. cholerae. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1507–1513. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.3.1507-1513.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Louwen R, Staals RH, Endtz HP, van Baarlen P, van der Oost J. The role of CRISPR-Cas systems in virulence of pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78:74–88. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00039-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bobay LM, Rocha EP, Touchon M. The adaptation of temperate bacteriophages to their host genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:737–751. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao Y, et al. Searching for a “hidden” prophage in a marine bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:589–95. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01450-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plaza N, et al. Bacteriophages in the control of pathogenic vibrios. Electron J Biotechnol. 2018;31:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbt.2017.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalatzis PG, Castillo D, Katharios P, Middelboe M. Bacteriophage interactions with marine pathogenic vibrios: implications for phage therapy. Antibiotics (Basel). 2018;7:pii: E15. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics7010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arndt D, et al. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W16–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kearse M, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer F, et al. The metagenomics RAST server - a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:386. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gertz EM, Yu YK, Agarwala R, Schäffer AA, Altschul SF. Composition-based statistics andtranslated nucleotide searches: improving the tBLASTn module of BLAST. BMC Biol. 2006;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates C, Wass M, Sternberg M. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:845–58. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larkin MA, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.