Highlights

-

•

Siliconomas of the breast develop as a result of implant rupture and present with many of the signs and symptoms of breast cancer.

-

•

MRI is the preferred study for diagnosis and a preoperative tissue sample should be attempted.

-

•

We present a patient with a giant breast siliconoma and perform a comprehensive literature review.

-

•

Our patient underwent a modified radical mastectomy with delayed closure.

-

•

The majority of patients should undergo surgery due to symptoms or the inability to rule out cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Siliconomas, Surgical resection, Case report, Literature review

Abstract

Introduction

Silicone prosthetics are widely used for breast augmentation and reconstruction. These devices may extrude free silicone into surrounding tissue, stimulating a granulomatous foreign body reaction. The resulting mass can mimic breast cancer.

Presentation of Case

71 year old female with a history of a ruptured silicone implant presents with an enlarging left breast mass. Exam demonstrated and ulcerated, fungating mass with active infection. CT scan demonstrated a 23 × 15 cm mass involving the breast and chest wall with axillary lymphadenopathy. Preoperative biopsies were inconclusive and the patient underwent a modified radical mastectomy. Pathology demonstrated a siliconoma.

Discussion

While benign, silicone granulomas of the breast can present similarly to malignancy and are an important differential in the diagnosis of a breast or axillary mass for appropriate patients. MRI is the study of choice and core needle biopsies cannot always establish the diagnosis preoperatively. PET scans can be falsely positive and the diagnosis requires an extensive workup to rule out cancer.

Conclusion

Siliconomas develop as a result of implant rupture and present with many of the signs and symptoms of breast cancer. The majority of patients should undergo surgery for symptom relief or to rule out cancer.

1. Introduction

Since their introduction in the 1960s, silicone prosthetics have been a mainstay in breast augmentation and reconstruction procedures. These devices carry the potential complication of rupture from either trauma or time-related decay. Silicone liquid can escape as the prosthetic shell weakens affecting the surrounding breast tissue. It has a tendency to spread and migrate due to its high fat solubility. The exact prevalence of rupture is unknown, but is likely underestimated as it can be asymptomatic [1]. Silicone granuloma (or siliconoma) describes the inflammatory physiological response to free liquid silicone that occurs in some patients. Winer et al. first described the histopathology of a siliconoma as [2]:

“degenerated anuclear stroma resembling necrobiosis of fibrous connective tissue surrounded by many irregular, oval, clear spaces or cavities. In other areas, this intervening stroma is invaded by a dense infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes. Some of the clear spaces are lined by a single layer of nucleated cells, which are syncytial giant cells. Other clear spaces contain foreign body giant cells.”

This description came from a patient who received cosmetic injections of liquid silicone. Legitimate medical providers abandoned this practice shortly after its complications came to light, though cosmetic injection is still performed illicitly in some countries. While silicone prosthetics are much safer, the pathological response following implant rupture is identical. Siliconomas can occur locally, manifest as lymphadenopathy, or present at a distant site due to migration of free. If neglected, siliconomas can create a firm mass, cause local tissue destruction, ulceration, scarring, and nerve damage [1].

This reaction to free silicone has been described in various types of prosthetic devices. However, involvement of breast implants brings up significant concern due to the burden of breast cancer in the modern healthcare environment. Any new breast mass causes modest to severe concern for cancer depending on the clinical context. While silicone granulomas have characteristic diagnostic features on imaging, their appearance may also mimic malignancy [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]].

We present a case report of a large breast siliconoma and perform a comprehensive review of the English literature. We highlight the diagnostic challenges related to this uncommon presentation.

The work has been done in line with the SCARE criteria [9].

2. Case report

In 2012, a 66-year-old female presented for mammographic evaluation of a left breast mass that had been growing and hardening over years. She described a history of breast augmentation with silicone implants in the 1980s as well as bilateral re-implantation with saline prosthetics years later due to previous implant rupture. Her mammogram revealed an abnormal density superior to her left breast implant, but the study was limited due to motion. A concurrent ultrasound exam was inconclusive, and a follow up MRI study was recommended to the patient.

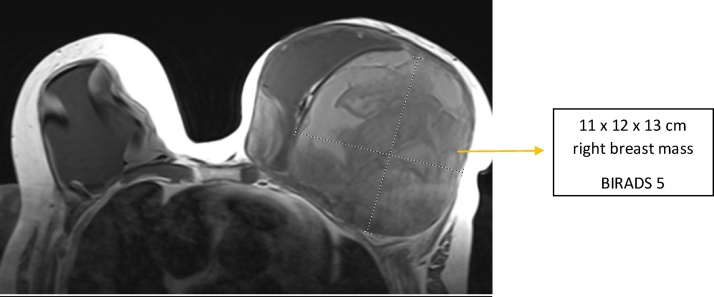

The patient received a non-contrast MRI about 9 months later due to concern for implant rupture (Fig. 1). This study showed an 11 × 12 × 13 cm mass in the outer half of her left breast that displaced her implant medially. Both implants appeared intact. She also had left axillary lymphadenopathy. The radiologist interpreted this exam as BI-RADS category 5, highly suggestive of malignancy. An ultrasound-guided biopsy of her left breast done several days later showed only benign fibrinous debris. Due to concern over discordant imaging and biopsy results, she had a repeat MRI done about a month later. This study was performed with contrast to better evaluate the presence of malignancy and need for a repeat biopsy.

Fig. 1.

Noncontract MRI of the breast on initial presentation.

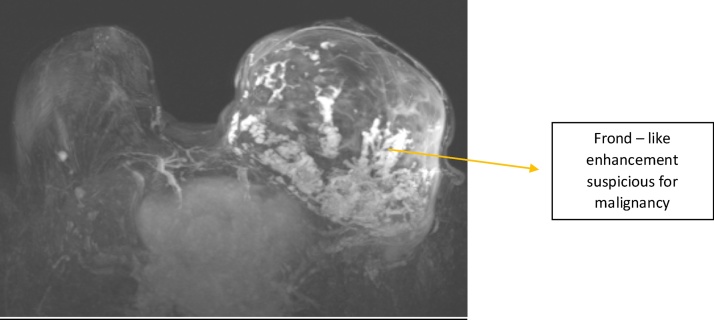

The second MRI again showed the 13 cm encapsulated complex mass in the outer half of the left breast (Fig. 2). The mass predominantly did not enhance, suggesting a large component to be hematoma. However, the posteroinferior periphery of the mass demonstrated extensive frond-like contrast enhancement highly concerning for malignancy (also BI-RADS 5). Her previously seen left axillary node was re-visualized. A re-biopsy of her left breast lesion was again recommended, however, the patient was lost to follow up for several years.

Fig. 2.

Contrast enhanced MRI of the breast.

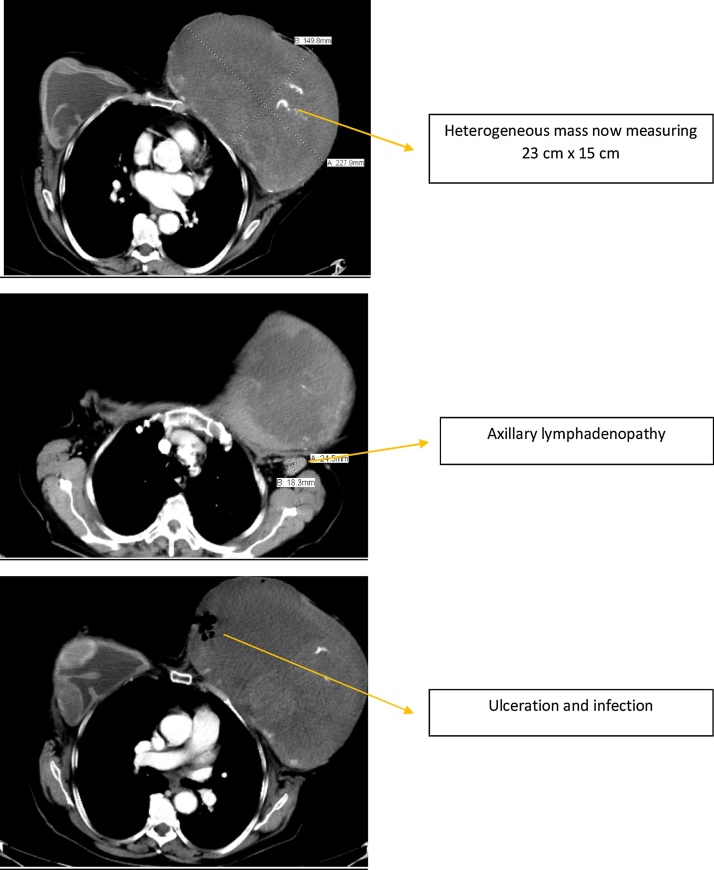

The patient presented again 5 years later to our institution, now 71 years of age. She described continued growth of her left breast over the past year with significant associated pain. She also stated that her left implant “fell out” on its own. On exam, a fungating mass with extensive ulceration occupied her medial left breast. The mass was large, firm and malodourous (Fig. 3). With a presumptive diagnosis of neglected breast cancer, she received several studies while hospitalized. A chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT with contrast showed her left breast mass to now measure 23 × 15 cm (Fig. 4). The mass was partially calcified with ulceration along its medial margin. It appeared to invade her pectoralis muscle, several intercostal muscles, and her 4th and 5th ribs. She had several prominent axillary lymph nodes on the left side. The remaining CT was largely unremarkable with no convincing evidence of distant metastases. She also had a bone scan and brain MRI around this time, neither of which had evidence of metastasis. A biopsy of her left breast yielded amorphous, acellular eosinophilic material with dystrophic calcifications interpreted as possible old necrosis or fibrin deposition. Another biopsy done about a week later had similar results, also without definitive evidence of cancer.

Fig. 3.

Presentation prior to surgery.

Fig. 4.

Current CT scan. The implant has been extruded and a large heterogeneous mass is seen.

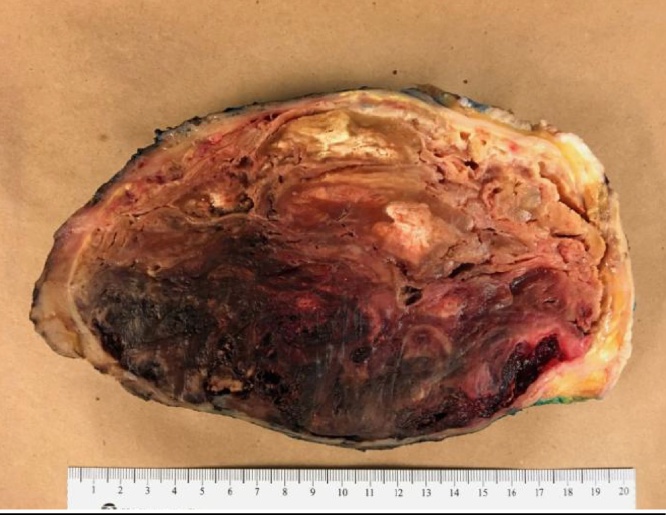

With both active infection of her breast as well as continued pain, she needed the mass removed regardless of its etiology. An extensive modified radical mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection was performed with final closure of the wound several days later. The final pathology of her breast mass (23.0 × 21.3 x 10.8 cm) demonstrated gross and microscopic changes consistent with ruptured silicone implant and subsequent hematoma, abscess, and skin ulceration; negative for malignancy (Fig. 5). Her nine dissected lymph nodes were reactive with additional soft tissue nodules and changes of silicone involvement; also negative for malignancy. The patient tolerated the procedure well and had an uneventful recovery.

Fig. 5.

Final specimen showing a predominately well-organized hematoma and a foreign body reaction.

3. Discussion

This patient’s clinical course was convoluted by her presentation to multiple providers over the years, lack of follow up, and diagnostic uncertainty towards her lesion. The mass was fungating and ulcerated with active infection resembling an advanced neglected tumor. Because fibrosis and hematoma comprised much of her breast lesion, the siliconoma aspect was missed until the final pathology results came back after surgery. The absence of metastases despite the size of the lesion and the 5-year delay in treatment makes malignancy less likely but it should not be excluded. Nevertheless, this case provides a prime example of how neglected silicone granuloma can mimic breast cancer, sparking an extensive workup with eventual surgery.

It is essential to understand the utility and limitations of various imaging studies for evaluating siliconomas. Implant rupture may appear on mammography, however, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI is the optimal modality to assess for rupture and siliconoma formation. An MRI should be done for every patient with implants who presents with a breast or axillary mass (6, 10). Typical MRI findings for siliconomas include evidence of implant collapse with free silicone particles outside the prosthetic shell and in the tissue surrounding the fibrous shell that forms around the implant. These findings in the context of rupture can reliably diagnose siliconoma and exclude malignancy [10,11]. Contrast enhancement of siliconomas on MRI is atypical but occurred in our patient and another reported by Grubstein et al. [6]. Sonographic evaluation of siliconomas may reveal echogenic lesions with a “snowstorm” appearance, however, findings may be nonspecific. The use of PET CT for oncological surveillance in patients with siliconomas may yield false-positive results; the inflammatory cells of silicone granulomas have increased FDG uptake from avid glycolysis (3, 5, and 8).

Pathological tissue specimens remain the gold standard for diagnosis of siliconomas. Biopsy was the final diagnostic step for many patients in our literature review. However, sampling error is always a concern. Multiple biopsies were not sufficient to rule out cancer in our patient given her imaging results. A personal history of breast cancer may also warrant further workup for patients with a negative biopsy [12].

There are no established guidelines for management of silicone granuloma, though excluding malignancy is paramount. What to do afterwards depends on severity of symptoms and patient preferences. Surgical removal is the only definitive method of relieving symptoms and avoiding future complications. Patients may prefer to forgo surgery for minimally or asymptomatic lesions [13]. However, surgical removal of siliconomas also prevents their obfuscation of future cancer screening and workup [10]. Thus, a patient’s risk for developing breast cancer should factor into their decision. Previous literature raised the question of whether siliconomas promote carcinogenesis or other systemic inflammatory diseases, however, not enough evidence exists to conclusively address the issue [11]. While diagnosis of siliconoma requires a high index of suspicion, greater awareness of their presentations and complications may prevent unnecessary tests and interventions in appropriate patients.

A comprehensive literature review was performed using PubMed and MEDLINE to include all cases of siliconomas mimicking breast cancer (Table 1). 13 cases were identified including this one [4,[6], [7], [8],[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. Siliconomas developed 4 weeks to 16 years following rupture. The most common presentation was a breast or axillary mass (9 patients, 69.2%). The remaining patients presented with pain or were diagnosed during surveillance imaging studies. A core needle biopsy was attempted in most cases but was only successful in obtaining a histologic diagnosis two-thirds of the time. Four patients underwent a PET scan and all 4 were falsely positive.

Table 1.

xxx.

| Author | Year | Number of patients | Age | Time since implantation (years) | Time since rupture (years) | Presentation | Workup | Procedures | Suspicion for malignancy | Final Pathology | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alduk et al [4] | 2015 | 1 | 56 | Unknown | 13 | Patient with history of silicone implant rupture and removal 13 years prior presents with a palpable lump at the time of screening mammography | Mammography- BIRADS 5 spiculated lesion. MRI- suggestive of malignancy. Biopsy showed only inflammatory changes | Mass resection | Very High | SG | Appearance of SG on mammogram classic for breast malignancy |

| Ali et al [13] | 2012 | 1 | 66 | 30 | 16 | Patient with significant smoking history presents with left breast mass fixed to chest wall and weight loss. | CXR had lesion concerning for lung cancer. CT thorax, US, and mammogram revealed 2 breast lesions resembling SG, but could not exclude cancer. Core biopsy showed only SG | None | High | SG | Patient declined resection upon learning benign nature of masses |

| Grubstein et al [6] | 2011 | 3 | 51 | 18 | >2 | Patient had left mastectomy with reconstruction for carcinoma and right sided augmentation 18 years prior. Her implants were replaced 2 years prior due to leak. She presents for a PET CT for oncological follow up. | PET CT showed bilateral LAD and soft tissue mass in breast with FDG uptake. US indicated silicone infiltration. MRI unremarkable. | 2 FNAs had only benign findings consistent with SG | High | SG | Positive PET CT concerning for cancer recurrence or lymphoma |

| 67 | Unknown | Unknown | Similar history as previous patient from this article who presents for oncological follow up with PET CT. | PET CT had pathological FDG uptake from breast masses as well as axillary, mediastinal, and internal mammary chain lymph nodes. US-guided FNA revealed benign pathology consistent with SG. | None | High | SG | Positive PET CT interpreted as “a suspicious malignant process.” | |||

| 56 | 7 | 2 years | Patient with history of breast augmentation and implant replacement due to rupture presents with a palpable mass. | Mammography nonspecific. US supported SG. MRI revealed nonspecific enhancing masses around implant. US-guided core biopsy revealed SG. | None | High | SG | ||||

| El-Charnoubi et al [14] | 2011 | 1 | 60 | 13 | Unknown | Painful mass with growth over 7-8 years. Patient presents again 3 months after initial workup/surgery with new tumor and erosion of overlying breast tissue. | Biopsy confirmed SG. US and MRI confirmed implant rupture. Biopsy again showed SG in recurrent lesion 3 months later. | Capsulectomy/mass excision. Mass excision and reconstruction |

High | SG – both initial and recurrent lesion | |

| Shepard et al [8] | 2010 | 1 | 67 | Unknown | Unknown | Patient with history of bilateral breast augmentation, known rupture, and stable SGs developed DCC near a SG in her left breast. She had a left mastectomy and radiation therapy. She presents for surveillance PET CT. | PET CT showed active lesions in her right breast. Mammogram and US supported SG. Biopsy consistent with SG, no evidence of cancer. | None | Moderate | SG | |

| Adams et al [11] | 2009 | 1 | 35 | 5 | Unknown | Palpable lump with clinically intact implants. Axillary mass also appeared during the workup of her initial lesion. | US and mammography suspicious for intracapsular rupture. MRI confirmed rupture. | Excisional biopsy of axillary node and re-implantation of ruptured prosthesis | Moderate | SG | |

| Ismael et al. [15] | 2005 | 1 | 50 | 5 | Unknown | Axillary LAD 5 years after surgical excision of breast cancer with reconstruction. | none discussed in article | Surgical excision of axillary mass and replacement of expander prosthesis | High | SG | Axillary mass concerning for cancer recurrence |

| Kao et al [12] | 1997 | 1 | 56 | 4 | Implant intact | Patient had bilateral breast cancer treated with mastectomies and axillary lymph node dissections 5 years prior and reconstruction a year later. She presented with parasternal pain. | New masses seen on CXR. CT thorax showed enlarged internal mammary chain lymph nodes. MRI nonspecific for the LAD, and implants appeared intact. CT-guided aspiration consistent with SG, no cancer. Subsequent PET CT was positive. | Thoracoscopic procedure done to remove suspicious lymph nodes. | High | SG | Strong concern for cancer recurrence. Another case of false positive PET CT. |

| Rivero et al [7] | 1994 | 1 | 40 | 11 | Implant intact | The patient had a strong FH of breast cancer and underwent bilateral prophylactic mastectomies 11 years prior. She had numerous complications with her implants requiring two replacement surgeries. She presents at age 40 with a palpable breast mass. | Mammogram showed residual breast tissue and 2 solid-appearing lesions. US showed solid lesions without typical features of lymph nodes. | Both masses excised | High | SG | The masses grossly resembled lymph nodes. Path consistent with SG. First reported case of intramammary silicone LAD. |

| Savrin et al [16] | 1979 | 1 | 28 | 5 | 4 weeks | Patient with history of trauma to breasts 4 weeks prior presents with bilateral capsular contractures and palpable breast lump. | FNA yielded no fluid aspirate, inconclusive. | Surgical excision of breast mass and replacement of both implants | Low | SG | Intraoperative findings indicated rupture of implant in breast with mass. |

CXR – Chest X-ray, LAD – Lymphadenopathy, SG – Silicone Granuloma, US – Ultrasound, MRI – Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

4. Conclusion

Siliconomas develop as a result of implant rupture and present with many of the signs and symptoms of breast cancer. The majority of patients will develop a painless breast or axillary mass. Others will have pain or be diagnosed incidentally during surveillance imaging. MRI is the preferred study for diagnosis and to rule out cancer although this is frequently very difficult. PET scans can be falsely positive and core needle biopsies can be inconclusive. The majority of patients should undergo surgery due to symptoms or the inability to rule out cancer.

Conflicts of interest

None of the Authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

None

Ethical approval

Approval has been given by the University of Texas Northeast ethics committee.

Consent

Written consent has been given.

Author contribution

Bryce Carson – Writing the paper.

Steven Cox MD – Data review and editing.

Hishaam Ismael MD – Study concept, literature review and helping in writing the article.

Registration of research studies

None.

Guarantor

Hishaam Ismael MD.

Contributor Information

Bryce Carson, Email: Bwcarson@utmb.edu.

Steven Cox, Email: Steven.cox@uthct.edu.

Hishaam Ismael, Email: Hishaam.ismael@uthct.edu.

References

- 1.Brown S.L., Silverman B.G., Berg W.A. Rupture of silicone-gel breast implants: causes, sequelae, and diagnosis. Lancet. 1997;22(November (9090)):1531–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winer L., Sternberg T.H., Lehman R. Tissue reaction to injected silicone liquids. Arch. Dermatol. 1964;90(6):588–593. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1964.01600060054010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adejolu M., Huo L., Rohren E. False-positive lesions mimicking breast cancer on FDG PET and PET/CT. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2012;198(March (3)) doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7130. W304-W314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alduk A.M., Brcic I., Prutki M. A rare cause of spiculated breast mass mimicking carcinoma: silicone granuloma following breast implant removal. Acta Clin. Belg. 2015;70(April (4)):153–154. doi: 10.1179/2295333714Y.0000000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuangsuwanich A., Warnnissorn M., Lohsiriwat V. Siliconoma of the breasts. Gland Surg. 2013;2(February (1)):46–49. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2013.02.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grubstein A., Cohen M., Steinmetz A. Siliconomas mimicking cancer. Clin. Imaging. 2011;35(May-June (35)):228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivero M.A., Schwartz D.S., Mies C. Silicone lymphadenopathy involving intramammary lymph nodes: a new complication of silicone mammoplasty. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1994;162(May (5)):1089–1090. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.5.8165987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shepherd S.M., Makariou E. Silicone granuloma mimicking breast cancer recurrence on PET CT. Breast J. 2010;16(September-October (3)):551–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2010.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. In J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu S., Lim A.A. Evaluation and;1; Treatment of surgical management of silicone mastitis. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2012;5(July-September (3)):193–196. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.101380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams S.T., Cox J., Rao G.S. Axillary silicone lymphadenopathy presenting with a lump and altered sensation in the breast: a case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2009;10(March (3)):6442. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-6442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kao C.C., Rand R.P., Holt C.A. Internal mammary silicone lymphadenopathy mimicking recurrent breast cancer. Plast Reconstr. Surg. 1997;99(1):225–229. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199701000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali L., Mcgivern D., Teoh R. Silicon granuloma mimicking lung cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;19(July) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Charnoubi W.A., Foged Henriksen T., Joergen Elberg J. Cutaneous silicone granuloma mimicking breast cancer after ruptured breast implant. Case Rep. Dermatol.Med. 2011:129138. doi: 10.1155/2011/129138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ismael T., Kelly J., Regan P.J. Rupture of an expander prosthesis mimics axillary cancer recurrence. Br. J. Plast Surg. 2005;58(October (7)):1027–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savrin R.A., Martin E.W., Jr, Ruberg R.L. Mass lesion of the breast after augmentation mammoplasty. Arch Surg. 1979;114(December (12)):1423–1424. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1979.01370360077010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]