Abstract

Aim

To describe the registry design of the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine – out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (JAAM‐OHCA) Registry as well as its profile on hospital information, patient and emergency medical service characteristics, and in‐hospital procedures and outcomes among patients with OHCA who were transported to the participating institutions.

Methods

The special committee aiming to improve the survival after OHCA by providing evidence‐based therapeutic strategies and emergency medical systems from the JAAM has launched a multicenter, prospective registry that enrolled OHCA patients who were transported to critical care medical centers or hospitals with an emergency care department. The primary outcome was a favorable neurological status 1 month after OHCA.

Results

Between June 2014 and December 2015, a total of 12,024 eligible patients with OHCA were registered in 73 participating institutions. The mean age of the patients was 69.2 years, and 61.0% of them were male. The first documented shockable rhythm on arrival of emergency medical services was 9.0%. After hospital arrival, 9.4% underwent defibrillation, 68.9% tracheal intubation, 3.7% extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 3.0% intra‐aortic balloon pumping, 6.4% coronary angiography, 3.0% percutaneous coronary intervention, 6.4% targeted temperature management, and 81.1% adrenaline administration. The proportion of cerebral performance category 1 or 2 at 1 month after OHCA was 3.9% among adult patients and 5.5% among pediatric patients.

Conclusions

The special committee of the JAAM launched the JAAM‐OHCA Registry in June 2014 and continuously gathers data on OHCA patients. This registry can provide valuable information to establish appropriate therapeutic strategies for OHCA patients in the near future.

Keywords: In‐hospital intensive care, Japanese Association for Acute Medicine, outcome, out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest, registry

Introduction

Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a leading public health problem in highly industrialized countries,1 with approximately 120,000 cases occurring every year in Japan,2 and patient survival after OHCA is still low. Since the 2000s, various important evidence on bystander interventions as well as procedures by emergency medical service (EMS) personnel at prehospital settings have been provided by the large‐scale Utstein‐based OHCA registries in Japan, such as the SOS‐KANTO Study,3 Utstein Osaka Project,4 and All‐Japan Utstein Registry.5

However, importantly, in‐hospital intensive care by medical staff after hospital arrival has not been extensively measured and evaluated in Japan, especially for OHCA patients with post‐cardiac arrest syndrome. Therefore, developing an integrated database in both pre‐ and in‐hospital OHCA treatments and understanding the actual situations of treatments among OHCA patients before and after hospital arrival will subsequently lead to improved OHCA outcomes.

The special committee that aims to improve the survival after OHCA by providing appropriate therapeutic strategies and emergency medical systems in the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) has launched a multicenter, prospective registry that enrolled OHCA patients who were transported to critical care medical centers or hospitals with an emergency care department.6 This is the first report to describe the registry design as well as its profile on hospital information, patient and EMS characteristics, and in‐hospital procedures and outcomes between June 2014 and December 2015, designated the JAAM‐OHCA Registry.

Methods

Settings and participation

The JAAM‐OHCA Registry encompasses all of Japan, which includes 288 critical care medical centers (CCMCs) certified by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare that can accept emergency and severely ill patients transported by ambulance, including OHCA patients.7 To be licensed as a CCMC, a hospital needs to have ≥20 beds and an intensive care unit (ICU) for severely ill patients, and it should be able to provide highly specialized treatments such as extracorporeal resuscitation (ECPR), targeted temperature management (TTM), or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), 24 h a day. Critical care medical centers as well as non‐CCMCs with an emergency care department can participate in this registry. Institutions that intend to participate in this registry must fill out the participation form (available from http://www.jaamohca-web.com/online-2) available on the Internet website of the JAAM‐OHCA Registry,6 and the corresponding person from each institution must be a regular member of the JAAM. The registry is ongoing and does not have a set ending of the registry period. The registry was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto University as the corresponding institution (available from http://www.jaamohca-web.com/download/), and each hospital also approved the JAAM‐OHCA Registry protocol as necessary.

Registry patients

Since June 1, 2014, the JAAM‐OHCA Registry has enrolled all patients who sustained a cardiac arrest in a prehospital setting, for whom resuscitation was attempted, and who were then transported to participating institutions. This registry excluded OHCA patients who did not receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) by physicians, those with in‐hospital cardiac arrest, or those who refused to participate in our registry, either personally or by family members. In addition, OHCA patients who were transported to the participating intuitions after receiving any procedures in another hospital were excluded. Personal identifiers were removed from the JAAM‐OHCA Registry database. To give patients or their family members the opportunity to refuse to be included in this registry, the special committee and each participating institution showed the document regarding opt‐out consent on the website and/or the board of the emergency department, and the requirement for informed consent of patients was waived.

Emergency medical service system in Japan

Details of the EMS system in Japan were previously described.2, 5 The 119 emergency telephone number is accessible anywhere in Japan; on receipt of a 119 call, an emergency dispatch center sends the nearest available ambulance to the site. Emergency services are provided 24 h every day. Each ambulance includes a three‐person unit providing life support. The most highly trained EMS personnel are called emergency life‐saving technicians. They are allowed to insert an i.v. line and an adjunct airway and use a semi‐automated external defibrillator for OHCA patients. Emergency life‐saving technicians are permitted to provide shocks without consulting a physician, and specially trained emergency life‐saving technicians are allowed to carry out tracheal intubation to administer adrenaline for OHCA patients. All EMS providers performed CPR, basically according to the Japanese CPR guidelines.8

Pre‐hospital resuscitation data were obtained from the All‐Japan Utstein Registry of the Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA) of Japan. Details of the registry were previously described.2, 5 Data were collected prospectively using the data form of the Utstein‐style international guideline for reporting OHCA.9 Collected data were as follows: prefecture, data, age, sex, witness status, bystander‐initiated CPR (chest compression only or conventional CPR), shocks by a public‐access automated external defibrillator, dispatcher instructions, first documented rhythm on EMS arrival, shocks by EMS personnel, advanced airway management (laryngeal mask airway, esophageal obturator airway, or tracheal intubation), i.v. fluid, adrenalin administration, and resuscitation time course as well as outcomes such as prehospital return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), 1‐month survival, and neurological status 1 month after OHCA.

Data collection and quality control

The JAAM‐OHCA Registry collected much information on OHCA patients after hospital arrival (available from: http://www.jaamohca-web.com/download/). During the registry period, anonymized data were fed into either the Internet form (available from: http://www.jaamohca.com/main/login) or the FAX‐OCR (electronic template provided by the registry) (Fig. S1) by physicians or medical staff in cooperation with physicians in charge of the patient. Data were logically checked by the system, and finally confirmed by the JAAM‐OHCA Registry committee, which is composed of specialists in emergency medicine and epidemiology. If the data form was incomplete, the committee member returned it to the respective institution and the data were completed as much as possible. In‐hospital data were systemically merged with the Utstein‐style prehospital data gathered from the FDMA, using the five key items: prefecture, emergency call time, age, gender, and cerebral performance category (CPC) 1 month after OHCA. The JAAM‐OHCA Registry collected data on the following three facets of in‐hospital care.

Hospital information

Each participating institution needed to enter the hospital information at the time of registration. The required information was as follows: prefecture, type of emergency department (CCMC or tertiary emergency medical facility, secondary emergency medical facility, other), total bed capacity, ICU bed capacity, pediatric ICU bed capacity, annual expected number of OHCA patients, number of physicians and nurses who treated an OHCA patient (daytime, night‐time duty), special area of physicians (yes, no) for OHCA treatments (such as acute care physicians, intensive care physicians, anesthesiologists, cardiologists, and pediatricians), use of end‐tidal carbon dioxide monitor during cardiopulmonary arrest (available, unavailable), ECPR use for an OHCA patient (unavailable, available any time, available daytime), having an ECPR protocol (yes, no), person who performed the ECPR priming (physician, clinical engineer, nurse), TTM for OHCA (available, unavailable), TTM protocol (yes, no), and other details such as target (maintenance) temperature (32, 33, 34, 35°C), duration (hours) of target (maintenance) temperature (12, 24, 48, 72 h), rewarming target temperature (°C), and duration of rewarming (h).

Baseline patient information

Baseline patient information was collected for both OHCA patient identification and entry criteria confirmation. First, information on the emergency call time from bystanders and hospital arrival, along with OHCA patient's sex and age, were included. Next, patients who met the following criteria were registered: (i) OHCA occurred in prehospital settings, (ii) was resuscitated by EMS personnel, or (iii) defibrillated by bystanders and then transported to the participating institutions, (iv) was resuscitated by physicians after hospital arrival.

In‐hospital data including treatments, arterial blood gases, and outcomes

In‐hospital data on OHCA patients after hospital arrival were prospectively collected using an original report form. The cause of arrest was defined as having cardiac (acute coronary syndrome, other heart disease, presumed cardiac cause) or non‐cardiac (cerebrovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, malignant tumors, external causes including traffic injury, fall, hanging, drowning, asphyxia, drug overdose, or any other external cause, and sudden infant death syndrome [only for children]) causes. The presumed cardiac cause category was a diagnosis by exclusion (i.e., the diagnosis was made when no evidence of a non‐cardiac cause was found). Diagnoses of cardiac or non‐cardiac origin were clinically made by the physician in charge. Other baseline information are as follows: departure of ambulance or helicopter with physicians (yes, no), body temperature upon hospital arrival (°C), ROSC status (ROSC after hospital arrival, ROSC before hospital arrival, no ROSC), and first documented rhythm upon hospital arrival (ventricular fibrillation/pulseless, ventricular tachycardia, pulseless electrical activity, asystole, and presence of pulse).

The reporting form also required actual detailed treatments for OHCA patients (i.e., defibrillation, tracheal intubation, ECPR, intra‐aortic balloon pumping, coronary angiography, PCI, TTM, drug administration during cardiopulmonary arrest [adrenalin, amiodarone, nifekalant, lidocaine, atropine, magnesium, and vasopressin]), and arterial blood gases measured initially on hospital arrival (pH, PaCO2 [mmHg], PaO2 [mmHg], HCO3 [mEq/L], base excess [mEq/L], lactate [mmol/L], and glucose [mg/dL]) before and after the first ROSC.

Outcome data were also prospectively collected and included the following: condition after hospital arrival (admitted to ICU/ward or death at the emergency department); and neurological status 1 month after OHCA occurrence using the Glasgow–Pittsburgh CPC scale (category 1, good cerebral performance; 2, moderate cerebral disability; 3, severe cerebral disability; 4, coma or vegetative state; and 5, death/brain death) or pediatric CPC scale (category 1, normal cerebral performance; 2, mild cerebral disability; 3, moderate cerebral disability; 4, severe cerebral disability; 5, coma or vegetative state; and 6, death/brain death) in patients aged ≤17 years. The neurological status of the survivors was evaluated by the medical staff in each institution 1 month after the event. Favorable neurological outcome was defined as a CPC of 1 or 2.9

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation for continuous values and their percentages for categorical values. All statistical analyses were carried out using STATA version 13 MP (Stata, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

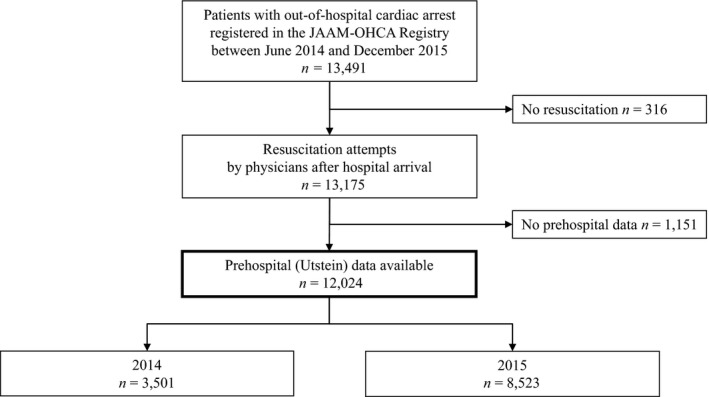

Figure 1 shows the overview of registered patients. During the study period, a total of 13,491 patients with OHCA were registered between June 2014 and December 2015. Excluding 316 patients who were not resuscitated by physicians after hospital arrival and 1,151 without the linkage of prehospital Utstein data, 12,024 patients (3,501 in 2014 and 8,523 in 2015) were eligible for the analysis. The linkage rate in this registry was 91.3% (12,024/13,175).

Figure 1.

Patient flow of the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine's out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (JAAM‐OHCA) Registry in 2014–2015.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of participating institutions as of the end of each year. The number of institutions increased from 56 in 2014 to 73 in 2015. In 2015, the institutions had a mean bed capacity of 608.0, and the annual expected number of OHCA patients transported to each institution was 152.0 per year. Among them, 60 (82.2%) institutions had ≥3 physicians treating OHCAs during the day. A total of 69 (94.5%) institutions could undertake ECPR for OHCA treatment and 71 (97.3%) could undertake TTM.

Table 1.

Hospital information for institutions that participated in the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine's out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) Registry, June 2014 to December 2015

| 2014 | 2015 (total) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of participating institutions | n = 56 | n = 73 |

| Area, n (%) | ||

| Hokkaido/Tohoku | 12 (21.4) | 13 (17.8) |

| Kanto | 11 (19.6) | 17 (23.3) |

| Tokai/Hokuriku | 5 (8.9) | 7 (9.6) |

| Kinki | 20 (35.7) | 23 (31.5) |

| Chugoku/Shikoku | 4 (7.1) | 7 (9.6) |

| Kyushu/Okinawa | 4 (7.1) | 6 (8.2) |

| Critical emergency medical center or tertiary emergency medical facility, n (%) | 40 (71.4) | 55 (75.3) |

| Bed capacity, mean (SD) | ||

| Total | 579.9 (315.4) | 608.0 (293.0) |

| Intensive care unit | 11.3 (8.1) | 12.9 (9.3) |

| Pediatric intensive care unit† | 25.7 (17.2) | 16.8 (14.7) |

| Annual expected number of OHCA cases, mean (SD) | 156.4 (119.0) | 152.0 (112.1) |

| ≥3 Physicians treated an OHCA case (daytime duty), n (%) | 44 (78.6) | 60 (82.2) |

| ≥3 Physicians treated an OHCA case (night‐time duty), n (%) | 30 (53.6) | 40 (54.8) |

| ≥3 Nurses treated an OHCA case (daytime duty), n (%) | 27 (48.2) | 32 (43.8) |

| ≥3 Nurses treated an OHCA case (night‐time duty), n (%) | 15 (26.8) | 19 (26.0) |

| Acute care physicians for OHCA treatment, n (%) | 53 (94.6) | 70 (95.9) |

| Intensive care physicians for OHCA treatment, n (%) | 43 (76.8) | 60 (82.2) |

| Anesthesiologists for OHCA treatment, n (%) | 43 (76.8) | 60 (82.2) |

| Cardiologists for OHCA treatment, n (%) | 51 (91.1) | 66 (90.4) |

| Pediatricians for OHCA treatment, n (%) | 40 (71.4) | 52 (71.2) |

| Use of ETCO2 monitor during cardiopulmonary arrest, n (%) | 31 (55.4) | 43 (58.9) |

| ECPR use for OHCA (any time or daytime), n (%) | 52 (92.9) | 69 (94.5) |

| ECPR protocol, n (%)‡ | 27 (51.9) | 37 (53.6) |

| Clinical engineer who performed ECPR priming, n (%)‡ | 45 (86.5) | 60 (87.0) |

| Targeted temperature management for OHCA, n (%) | 54 (96.4) | 71 (97.3) |

| Targeted temperature management protocol, n (%) | 34 (63.0) | 45 (63.4) |

| Target (maintenance) temperature, °C; n (%)§ | ||

| 32 (hypothermia) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| 33 (hypothermia) | 5 (14.7) | 4 (8.9) |

| 34 (hypothermia) | 26 (76.5) | 38 (84.4) |

| 35 (normothermia) | 2 (5.9) | 2 (4.4) |

| Duration of target (maintenance) temperature, h; n (%)§ | ||

| 12 | 2 (5.9) | 2 (4.4) |

| 24 | 25 (73.5) | 31 (68.9) |

| 48 | 6 (17.6) | 11 (24.4) |

| 72 | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| Rewarming target temperature, °C; mean (SD)§ | 35.0 (6.2) | 35.3 (5.4) |

| Duration of rewarming, h; mean (SD)‡ | 38.4 (18.5) | 40.8 (18.8) |

†Calculated for three (2014) and six (2015) institutions with a pediatric intensive care unit.

‡Calculated for 52 (2014) and 69 (2015) institutions with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) use.

§Calculated for 34 (2014) and 45 (2015) institutions having body temperature management protocol.

ETCO2, end‐tidal carbon dioxide; OHCA, out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of 12,024 OHCA patients. The mean age was 69.2 years, and the proportion of children aged ≤17 years and adults aged ≥65 years was 2.4% and 68.8%, respectively. Male patients accounted for 61.0% of the cohort. The proportion of OHCAs with a cardiac cause was 51.3%. In this registry, 24.4% patients had ROSC after hospital arrival, and 9.3% had already received ROSC on arrival, 4.2% had ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia, 19.7% had pulseless electrical activity, 66.9% had asystole, and 9.2% had pulse as the first documented rhythm after hospital arrival.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients registered in the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine's out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest Registry, June 2014 to December 2015

| Total (n = 12,024) | 2014 (n = 3,501) | 2015 (n = 8,523) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years; mean (SD) | 69.2 (19.7) | 68.7 (19.7) | 69.4 (19.7) |

| Age group, years; n (%) | |||

| 0–17 | 289 (2.4) | 86 (2.5) | 203 (2.4) |

| 18–64 | 3,467 (28.8) | 1,050 (30.0) | 2,417 (28.4) |

| ≥65 | 8,268 (68.8) | 2,365 (67.6) | 5,903 (69.3) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 7,331 (61.0) | 2,113 (60.4) | 5,218 (61.2) |

| Cause, n (%) | |||

| Cardiac | 6,163 (51.3) | 1,746 (49.9) | 4,417 (51.8) |

| Non‐cardiac | 5,861 (48.7) | 1,755 (50.1) | 4,106 (48.2) |

| Departure of ambulance or helicopter with physicians, n (%) | 1,523 (12.7) | 465 (13.3) | 1,058 (12.4) |

| Body temperature at hospital arrival, mean (SD)† | 35.2 (2.2) | 35.3 (2.0) | 35.2 (2.3) |

| ROSC status, n (%) | |||

| ROSC after hospital arrival | 2,933 (24.4) | 861 (24.6) | 2,072 (24.3) |

| ROSC at hospital arrival | 1,116 (9.3) | 322 (9.2) | 794 (9.3) |

| No ROSC | 7,975 (66.3) | 2,318 (66.2) | 5,657 (66.4) |

| First documented rhythm at hospital arrival, n (%) | |||

| VF/pulseless VT | 501 (4.2) | 165 (4.7) | 336 (3.9) |

| PEA | 2,372 (19.7) | 696 (19.9) | 1,676 (19.7) |

| Asystole | 8,046 (66.9) | 2,330 (66.6) | 5,716 (67.1) |

| Presence of pulse | 1,105 (9.2) | 310 (8.9) | 795 (9.3) |

†Calculated for patients having measured body temperature.

PEA, pulseless electrical activity; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; SD, standard deviation; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular fibrillation.

Table 3 shows the prehospital characteristics of patients based on the Utstein‐style data from the FDMA. Of all OHCA, 36.4% were witnessed by bystanders and 53.3% were not. Approximately 42.6% of patients received bystander‐initiated CPR, and 1.8% received shocks using a public‐access automated external defibrillator. First documented shockable rhythm at EMS arrival was 9.0%. Regarding the prehospital treatment by EMS personnel, 12.9% of patients received shocks, 43.5% received advanced airway management, and 25.1% received adrenaline. The mean time interval from the 119 call to CPR started by EMS at the scene, and from the 119 call to hospital arrival, were 10.2 and 34.5 min, respectively.

Table 3.

Prehospital characteristics of patients registered in the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine's out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest Registry, June 2014 to December 2015

| Total (n = 12,024) | 2014 (n = 3,501) | 2015 (n = 8,523) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Witness status, n (%) | |||

| Witnessed by bystanders | 4,379 (36.4) | 1,303 (37.2) | 3,076 (36.1) |

| Family member | 2,469 (20.5) | 733 (20.9) | 1,736 (20.4) |

| Non‐family member | 1,910 (15.9) | 570 (16.3) | 1,340 (15.7) |

| Witnessed by EMS personnel | 1,097 (9.1) | 303 (8.7) | 794 (9.3) |

| Not witnessed | 6,410 (53.3) | 1,841 (52.6) | 4,569 (53.6) |

| Unknown | 138 (1.1) | 54 (1.5) | 84 (1.0) |

| Bystander‐initiated CPR, n (%) | 5,127 (42.6) | 1,463 (41.8) | 3,664 (43.0) |

| Shock by a public‐access AED, n (%) | 211 (1.8) | 58 (1.7) | 153 (1.8) |

| Dispatcher instructions, n (%) | 5,791 (48.2) | 1,598 (45.6) | 4,193 (49.2) |

| VF/pulseless VT as the first documented rhythm at EMS arrival, n (%) | 1,088 (9.0) | 335 (9.6) | 753 (8.8) |

| Shocks by EMS personnel, n (%) | 1,552 (12.9) | 477 (13.6) | 1,075 (12.6) |

| Advanced airway management, n (%) | 5,227 (43.5) | 1,551 (44.3) | 3,676 (43.1) |

| Intravenous fluid, n (%) | 4,537 (37.7) | 1,274 (36.4) | 3,263 (38.3) |

| Adrenaline administration, n (%) | 3,021 (25.1) | 885 (25.3) | 2,136 (25.1) |

| Call to CPR started by EMS personnel, min; mean (SD)† | 10.2 (5.9) | 10.1 (5.8) | 10.3 (5.9) |

| Call to hospital arrival, min; mean (SD)† | 34.5 (11.8) | 34.7 (11.9) | 34.5 (11.7) |

| Prehospital ROSC, n (%) | 1,465 (12.2) | 457 (13.1) | 1,008 (11.8) |

†Calculated only for patients having measured data.

AED, automated external defibrillator; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMS, emergency medical service; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; SD, standard deviation; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Table 4 presents in‐hospital data of OHCA patients. After hospital arrival, 9.4% received defibrillation, 68.9% tracheal intubation, 3.7% ECPR, 3.0% intra‐aortic balloon pumping, 6.4% coronary angiography, 3.0% PCI, 6.4% TTM, and 81.1% adrenaline. Regarding the arterial blood gases measured initially at hospital arrival after the first ROSC, the mean values were as follows: pH, 7.003; PaCO2, 69.7 mmHg; PaO2, 191.8 mmHg; HCO3, 15.8 mEq/L; base excess, −15.1 mEq/L; lactate, 12.0 mmol/L; and glucose, 261.7, mg/dL.

Table 4.

In‐hospital advanced treatments, drug administration, and arterial blood gases among patients registered in the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine's out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest Registry, June 2014 to December 2015

| Total (n = 12,024) | 2014 (n = 3,501) | 2015 (n = 8,523) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defibrillation, n (%) | 1,131 (9.4) | 345 (9.9) | 786 (9.2) |

| Tracheal intubation after hospital arrival, n (%) | 8,290 (68.9) | 2,439 (69.7) | 5,851 (68.6) |

| Extracorporeal life support, n (%) | 445 (3.7) | 136 (3.9) | 309 (3.6) |

| Intra‐aortic balloon pumping, n (%) | 366 (3.0) | 123 (3.5) | 243 (2.9) |

| Coronary angiography, n (%) | 767 (6.4) | 235 (6.7) | 532 (6.2) |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | 365 (3.0) | 117 (3.3) | 248 (2.9) |

| Targeted temperature management, n (%) | 770 (6.4) | 237 (6.8) | 533 (6.3) |

| Drug administration during cardiac arrest (multiple choice) | |||

| Adrenaline, n (%) | 9,749 (81.1) | 2,883 (82.3) | 6,866 (80.6) |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 500 (4.2) | 147 (4.2) | 353 (4.1) |

| Nifekalant, n (%) | 60 (0.5) | 31 (0.9) | 29 (0.3) |

| Lidocaine, n (%) | 78 (0.6) | 27 (0.8) | 51 (0.6) |

| Atropine, n (%) | 214 (1.8) | 69 (2.0) | 145 (1.7) |

| Magnesium, n (%) | 136 (1.1) | 42 (1.2) | 94 (1.1) |

| Vasopressin, n (%) | 54 (0.4) | 22 (0.6) | 32 (0.4) |

| Arterial blood gases at hospital arrival, mean (SD)† | |||

| Before first ROSC | |||

| pH | 6.867 (0.200) | 6.866 (0.201) | 6.867 (0.200) |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 91.9 (38.1) | 91.1 (37.9) | 92.2 (38.2) |

| PaO2, mmHg | 55.2 (71.3) | 56.6 (74.9) | 54.7 (69.7) |

| HCO3, mEq/L | 15.4 (5.9) | 15.3 (5.7) | 15.5 (6.0) |

| Base excess, mEq/L | −18.3 (8.4) | −18.2 (8.5) | −18.3 (8.4) |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 14.2 (6.0) | 14.1 (6.2) | 14.2 (6.0) |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 226.3 (142.9) | 228.1 (147.4) | 225.6 (141.1) |

| After first ROSC | |||

| pH | 7.003 (0.223) | 6.995 (0.215) | 7.007 (0.226) |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 69.7 (33.3) | 70.2 (31.7) | 69.5 (34.0) |

| PaO2, mmHg | 191.8 (152.0) | 194.4 (152.9) | 190.7 (151.7) |

| HCO3, mEq/L | 15.8 (6.1) | 15.8 (6.4) | 15.8 (5.9) |

| Base excess, mEq/L | −15.1 (8.6) | −15.2 (8.8) | −15.1 (8.5) |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 12.0 (6.1) | 12.0 (5.6) | 11.9 (6.3) |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 261.7 (118.7) | 266.3 (122.8) | 259.7 (116.9) |

| Implementation of 12‐lead ECG after ROSC, n (%) | 8,750 (72.8) | 2,544 (72.7) | 6,206 (72.8) |

| ST‐elevation | 740 (6.2) | 214 (6.1) | 526 (6.2) |

†Calculated only for patients having measured data.

ECG, electrocardiogram; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; SD, standard deviation.

Table 5 shows the outcomes of 12,024 OHCA patients. The proportions of admission to ICU/ward and 1‐month survival after OHCA were 25.4% and 7.2%, respectively. The proportions of CPC 1 or 2 at 1 month after OHCA were 3.9% among adult patients and 5.5% among pediatric patients.

Table 5.

Outcomes of patients registered in the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine's out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) Registry, June 2014 to December 2015

| Total (n = 12,024) | 2014 (n = 3,501) | 2015 (n = 8,523) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition after hospital arrival, n (%) | |||

| Admitted to ICU/ward | 3,058 (25.4) | 921 (26.3) | 2,137 (25.1) |

| Death at the ED | 8,966 (74.6) | 2,580 (73.7) | 6,386 (74.9) |

| 1‐month survival, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 871 (7.2) | 252 (7.2) | 619 (7.3) |

| Hospitalized | 454 (3.8) | 128 (1.1) | 326 (2.7) |

| Discharge to survival | 372 (3.1) | 102 (0.8) | 270 (2.2) |

| Unknown | 45 (0.4) | 22 (0.2) | 23 (0.2) |

| No | 11,153 (92.8) | 3,249 (92.8) | 7,904 (92.7) |

| CPC 1 month after OHCA (adults aged ≥18 years), n (%) | (n = 11,735) | (n = 3,415) | (n = 8,320) |

| CPC 1 | 352 (3.0) | 96 (2.8) | 256 (3.1) |

| CPC 2 | 104 (0.9) | 28 (0.8) | 76 (0.9) |

| CPC 3 | 124 (1.1) | 41 (1.2) | 83 (1.0) |

| CPC 4 | 259 (2.2) | 81 (2.4) | 178 (2.1) |

| CPC 5 | 10,896 (92.9) | 3,169 (92.8) | 7,727 (92.9) |

| PCPC 1 month after OHCA (children aged 0–17 years), n (%) | (n = 289) | (n = 86) | (n = 203) |

| PCPC 1 | 14 (4.8) | 2 (2.3) | 12 (5.9) |

| PCPC 2 | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) |

| PCPC 3 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| PCPC 4 | 5 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.5) |

| PCPC 5 | 10 (3.5) | 3 (3.5) | 7 (3.4) |

| PCPC 6 | 257 (88.9) | 80 (93.0) | 177 (87.2) |

CPC, cerebral performance category; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; PCPC, pediatric cerebral performance category.

Discussion

The special committee of the JAAM has launched a multicenter, prospective registry (the JAAM‐OHCA Registry) that focuses on OHCA patients who were transported by EMS personnel to participating institutions (either CCMCs or hospitals with an emergency care department) since June 2014. This report describes this registry's profile and briefly presented the characteristics of 12,024 OHCA patients registered between June 2014 and December 2015.

To improve the survival after OHCA, the JAAM‐OHCA Registry established the following purposes. First, and most importantly, the JAAM established a framework for the multicenter registry that can include CCMCs or hospitals with an emergency care department across Japan. Second, the special committee developed a standard registry form to capture both in‐hospital procedures by medical staff and the emergency systems of the receiving institutions in order to understand the actual situations and treatments for OHCA patients after hospital arrival. Finally, findings from the JAAM‐OHCA Registry can provide useful evidence to improve systematic therapeutic strategies and neurological outcomes among OHCA patients after hospital arrival. They can also contribute to revisions of the CPR guidelines by evaluating the effects of various in‐hospital treatments, such as advanced procedures and drug therapies. Importantly, the effectiveness of these treatments for OHCA patients is still under debate.10 Therefore, by obtaining data of a large number of OHCA patients across Japan, this nationwide registry can assist considerably in solving these problems in the future.

In Japan, prehospital emergency care systems are well developed.2 The All‐Japan Utstein Registry of the FDMA, a nationwide prospective, population‐ and Utstein‐based registry, enabled us to evaluate the effectiveness of continuous chest compressions and defibrillation by lay‐rescuers5 and the importance of continuously improving the chain of survival at the population level.11 In the JAAM‐OHCA Registry, the special committee has systemically merged in‐hospital databases and the All‐Japan Utstein Registry database by focusing on the use of key items in all data sources. As a result, the JAAM‐OHCA Registry obtained high‐quality prehospital resuscitation data and reduced the need for multiple data input by medical staff in each institution. The linkage rate in this registry was 91.3%, which is higher than the 80.5% linkage rate in the Out‐of‐Hospital Cardiac Arrest Outcomes project with the national database in the UK;12 however, further efforts to improve the linkage rate (e.g., communication between EMS personnel and medical staff in key items or the development of personal identification systems) are need for the accuracy of the JAAM‐OHCA Registry database.

Recently, several studies such as PAROS13 in Asia, EuReCa14 in Europe, and CARES15 and ROC16 in the USA have been launched as large‐scale OHCA registries, because of the great need for high‐quality data collection that can be used for improving OHCA outcomes, like the JAAM‐OHCA Registry. In our registry, the number of participating CCMCs or tertiary emergency medical facilities was 73 during this registry period, and further efforts to increase the number of participating institutions are needed. In a previous report in Japan,17 nearly 30% of OHCA patients were transported to CCMCs, and the JAAM‐OHCA Registry is planning to enroll ≥30,000 OHCA patients from all 288 CCMCs per year. To increase the registered OHCA patients and enhance the generalizability of this database, the special committee must also reinforce activities to raise awareness for the dissemination of the JAAM‐OHCA Registry through its website, annual and/or regional meetings, and mass media. Furthermore, by receiving suggestions regarding user‐friendly system revisions as well as item additions that can bridge knowledge gaps in resuscitation science from investigators in each participating institution, the special committee will continue to revise the JAAM‐OHCA Registry system to maintain a high‐quality database.

Importantly, patient survival after OHCA is still low, and it needs to improve worldwide. Even in the JAAM‐OHCA Registry, the proportion of 1‐month survival with a favorable neurological outcome after OHCA was only ≤5% among OHCA patients. To effectively use limited medical resources, further evidence regarding transportation conditions as well as the effect of advanced treatments would lead to improving the revisions of treatment protocols and/or resuscitation guidelines for OHCA patients, especially from the large‐scale comprehensive database of both pre‐ and in‐hospital information. The JAAM‐OHCA Registry is suitable for this purpose as it collects real‐world data from Japan.

Conclusion

The special committee of the JAAM launched the JAAM‐OHCA Registry in June 2014, which continuously gathers data on OHCA patients. This registry can provide valuable information to establish appropriate therapeutic strategies for OHCA patients in the near future.

Disclosure

Approval of the research protocol: The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto University as the corresponding institution, and each hospital also approved the JAAM‐OHCA Registry protocol as necessary.

Informed consent: The requirement for informed consent of patients was waived.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: This study was not registered.

Animal Studies: N/A.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. (A–C) FAX‐OCR form developed for the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine's out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest Registry.

Acknowledgements

The special committee is deeply indebted to all members and institutions of the JAAM‐OHCA Registry for their contribution. The participating institutions of the JAAM‐OHCA Registry are listed at the following URL (http://www.jaamohca-web.com/list/). This registry was supported by research funding from the JAAM and a scientific research grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (grant nos. 16K09034 and 15H05006) and the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (grant no. 25112601), and was constructed based on the design, concept, and system of the CRITICAL Study in Osaka as well as “The establishment of data registry system for evaluating emergency medical decision regarding cardiovascular diseases (J‐ACUTE).” We also thank Ms. Narumi Funayama and Mr. Hiroki Chiba for their support of the JAAM‐OHCA Registry.

References

- 1. Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW et al Part1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2015; 132: S315–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ambulance Service Planning Office of Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan . Effect of first aid for cardiopulmonary arrest (4 April 2008). Available from: http://www.fdma.go.jp/neuter/topics/fieldList9_3.html. (in Japanese).

- 3. SOS‐KANTO study group . Cardiopulmonary resuscitation by bystanders with chest compression only (SOS‐KANTO): an observation study. Lancet 2007; 369: 920–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iwami T, Kawamura T, Hiraide A et al Effectiveness of bystander‐initiated cardiac‐only resuscitation for patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2007; 116: 2900–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kitamura T, Kiyohara K, Sakai T et al Public‐access defibrillation and out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in Japan. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016; 375: 1649–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The special committee for aiming to improve survival after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) by providing evidence‐based therapeutic strategy and emergency medical system from the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM). The website of the JAAM‐OHCA Registry. Available from: http://www.jaamohca-web.com/. (in Japanese).

- 7. The Japanese Association for Acute Medicine . The website of the JAAM. Available from: http://www.jaamohca-web.com/. (in Japanese).

- 8. Japan Resuscitation Council . 2015 Japanese guidelines for emergency care and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Tokyo: Igaku‐Shoin, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobs I, Nadkarni V, Bahr J et al Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update and simplification of the Utstein templates for resuscitation registries: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Councils of Southern Africa). Circulation 2004; 110: 3385–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hollenberg J, Svensson L, Rosenqvist M. Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: 10 years of progress in research and treatment. J. Intern. Med. 2013; 273: 572–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T et al Nationwide improvements in survival from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrests in Japan. Circulation 2012; 126: 2834–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rajagopal S, Booth SJ, Brown TP et al Data quality and 30‐day survival for out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in the UK out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest registry: a data linkage study. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e017784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ong ME, Shin SD, Tanaka H et al Pan‐Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS): rationale, methodology, and implementation. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2011; 18: 890–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grasner JT, Herlitz J, Koster RW, Rosell‐Ortiz F, Stamatakis L, Bossaert L. Quality management in resuscitation–towards a European cardiac arrest registry (EuReCa). Resuscitation 2011; 82: 989–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McNally B, Robb R, Mehta M et al Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest surveillance—Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), United States, October 1, 2005–December 31, 2010. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2011; 60: 1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis DP, Garberson LA, Andrusiek DL et al A descriptive analysis of Emergency Medical Service Systems participating in the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) network. Pre‐hosp. Emerg. Care. 2007; 11: 369–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kajino K, Iwami T, Daya M et al Impact of transport to critical care medical centers on outcomes after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2010; 81: 549–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. (A–C) FAX‐OCR form developed for the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine's out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest Registry.