Abstract

Background:

Alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by patchy loss of hair from scalp, beard, eyebrows, or rarely even body hair. Rarely, the disease can be widespread and severe leading to loss of entire scalp and body hair causing apprehension and psychological stress in patients. Management of such cases is equally difficult with the available options of topical and systemic immunosuppressant. Tofacitinib, JAK3 inhibitor, is emerging as a promising drug for the management of severe and resistant cases of AA/totalis/universalis.

Objective:

Our study aims to show the effectiveness of oral tofacitinib in the treatment of alopecia universalis (AU).

Methods:

Six patients diagnosed with AU/alopecia totalis duration of disease 6 months–15 years refractory to other treatments were selected and were started on oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily up to 10 mg BID and were followed up every 4 weeks. The efficacy was measured by hair regrowth using photographic assessment, Severity of Alopecia Tool score, and physical examination. Patients will be followed up for 6 months after stopping treatment for assessing disease relapse.

Results:

All our six patients showed dramatic response to oral tofacitinib. Patients were followed up every 4 weeks, and results were assessed. Significant hair regrowth was evident in all the patients by the end of 12 weeks. Currently, four of our patients are on oral tofacitinib 10 mg BID and are under follow-up. There was no relapse in one patient after stopping drug for 4 months. Another patient started developed AA patches in the eyebrows within 2 months of stopping tofacitinib. Acneiform eruptions were seen in two patients which were managed with topicals.

Conclusion:

In our patients, tofacitinib successfully alleviated AU in the absence of significant adverse side effects. We recommend that further controlled studies be required to establish safety and confirm efficacy.

Key words: Alopecia universalis, Janus kinase inhibitors, tofacitinib

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease with a lifetime prevalence of 2%.[1] Loss of immune privilege leads to arrest of hairs in the anagen phase resulting in nonscarring hair loss. AA is characterized by small patches of hair loss within normal hair-bearing skin. The variants of AA include alopecia totalis (AT), characterized by complete loss of scalp hair; alopecia universalis (AU), characterized by complete loss of scalp and other body hair; and ophiasis pattern AA, characterized by hair loss localized to the temporal and occipital scalp. Loss of hair is considered as an autoimmune process leading to chronic inflammation due to the presence of organ-specific CD8+ T-cell-dependent response mainly affecting hair follicles.[2] Various triggers such as infections, trauma, hormones, and stress are known to worsen the disease.[3] Genetic component plays an important role with likelihood of severe symptoms seen in first-degree relative.[4] Association with other autoimmune diseases such as vitiligo, lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, thyroid disease, allergic rhinitis, pernicious anemia, diabetes mellitus, and rheumatoid arthritis is known.[5] Topical/intralesional steroids and various immunosuppressants had been tried with varying rate of success. AT and universalis are often resistant to such therapies and are prone to frequent relapses.

AA occurs as a result of breech in the immune privilege of anagen hair follicles. It is mediated by the suppression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Class I and shutdown of pro-inflammatory mechanisms including action of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), mast cells, and natural killer cells. Disruption in these mechanisms leads to collapse of immune privilege leading to onset and progression of AA. The immune mechanism is mediated by CD8+ NKG2D+ T-cells through interleukin (IL)-15-positive feedback loop within follicular epithelial cells, mediated through Janus kinase (JAK) signaling pathway.[6] There is an accumulation of CD8+/CD4+ lymphocytes and APC around hair follicles, and increase in the substance P mediates transition from anagen phase to catagen phase resulting in characteristic nonscarring hair loss. Hair loss is induced due to arrest of growth phase leading to premature senescence rather than direct immune-mediated follicular destruction.[7] Selective involvement of black hairs suggests that the autoantigen displayed by MHC I is both anagen and melanogenesis associated. The treatment of AA is challenging, and there is no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapy.[8] While a variety of therapies are commonly used, none of them are reliably effective, especially for the treatment of severe AA, AT, and AU.[8] An important therapeutic insight was the discovery that blockade of common signaling pathways downstream of cytokine receptors, in particular JAK/STAT, could reverse AA in mice.[9]

METHODS

Six patients diagnosed with AU/AT refractory to immunosuppressants and with rapidly progressing disease were selected. Detailed history regarding the disease process, previous treatments, and associated comorbidities was recorded. Complete hemogram, liver function test, renal parameters, ultrasound abdomen, chest X-ray, and Mantoux test were done. Herpes zoster vaccination was given for all the patients before starting the therapy. Severity of AA was assessed using the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score. A patient was initially started on oral tofacitinib 5 mg BID for 4 weeks later, and the dose was increased up to 10 mg BID. Treatment response was assessed based on physical assessment, photographic evaluation, dermoscopic changes, and SALT score analysis. Adverse reactions were monitored by blood investigations done at 2 monthly interval. All the patients will be followed up for at least 6 months after stopping the therapy to assess any relapse.

RESULTS

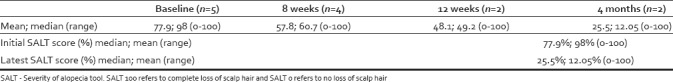

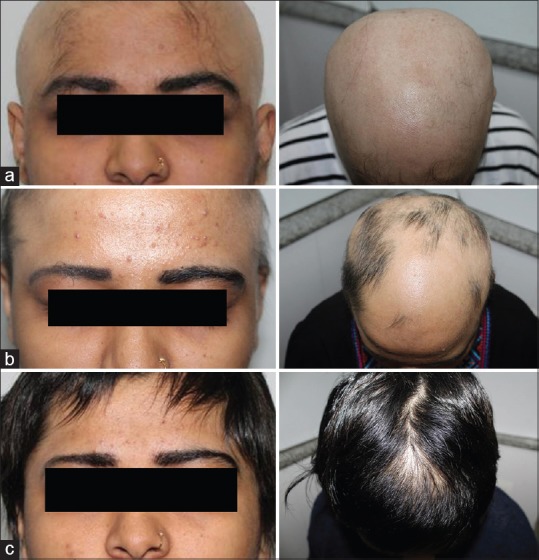

All our patients (5 patients with AU, 1 patient with AT) showed dramatic response to oral tofacitinib. The mean treatment duration was 3–6 months. Patient characteristics with treatment protocol are listed in Table 1. Baseline and subsequent SALT score analysis and median change are mentioned in Table 2. All the patients were initially reviewed after 4 weeks, and the dose was increased to 10 mg BID. By 8 weeks, there was a formation of vellus hair follicles [Figure 1]. Therapy was continued till complete regrowth of hairs. Among our patients, initial regrowth was first seen over the eyebrows and beard followed by the scalp. Our patients are currently in follow-up and one among them is under remission after stopping the drug for 4 months. One patient relapsed with loss of hair over eyebrows within 2 months of stopping the drug. Clinical representative photographs of response to the drug are presented in Figure 2. No serious adverse side effects were encountered. Two of our patients developed acneiform eruptions which were managed with topicals.

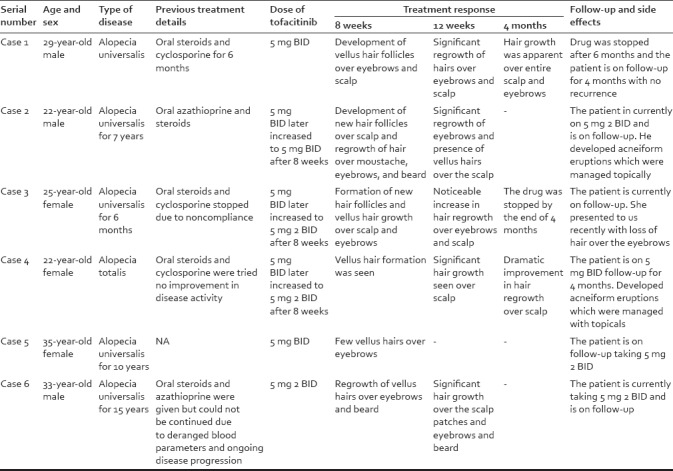

Table 1.

Patient details, drug dosage and treatment response pattern

Table 2.

Mean, median of SALT score at baseline and at subsequent visits

Figure 1.

(a) Pre- and posttreatment improvement in regrowth of eyebrows (kajal applied by the patient in pretreatment picture at 4 months. (b) Pre- and posttreatment regrowth of scalp hairs by 4 months. (c) Dermoscopy picture showing vellus hairs at 8 weeks and 12 weeks showing terminal hairs

Figure 2.

(a) Photographs taken at baseline. (b) At 12 weeks of therapy. (c) At 4 months after starting tofacitinib

DISCUSSION

JAK inhibitors (jakinibs) are groups of drugs that inhibit the JAK family of enzymes interfering with the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Tofacitinib is a selective targeted kinase inhibitor that it mainly inhibits JAK3, thus blocking the upregulation of interferon (IFN)-gamma in CD8+ lymphocytes.[9] Therapeutically, antibody-mediated blockade of IFN-γ, IL-2, or IL-15 receptor β prevented disease development, reducing the accumulation of CD8 (+) NKG2D (+) T-cells in the skin and the dermal IFN response in a mouse model of AA.[9] Systemically administered pharmacological inhibitors of JAK family protein tyrosine kinases, downstream effectors of the IFN-γ and γc cytokine receptors, eliminated the IFN signature and prevented the development of AA. There is an interruption of the feedback loop, and the hair follicles are able to return to anagen. Tofacitinib was initially FDA approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.[10] It was after a milestone paper published by Craiglow and King showing that the Renbok phenomenon of hair growth in AA patches in a psoriasis patient treated with tofacitinib provoked further research and use of this drug in AA.[11] It also currently has been investigated for its benefits in psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, and prevention of transplant rejection. Side effects of jakinibs are anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia due to JAK2 inhibition. Deranged lipid profile was seen in RA patients taking tofacitinib. Other serious adverse effects are bacterial and fungal infections. There are reports of reactivation of TB and herpes zoster in patients during Phase 3 trials. Further studies are required to establish the drug safety profile and long-term side effects.

Other studies point to a role for JAK inhibition in treating AA. In an uncontrolled retrospective study by Liu et al. of 90 adults with AT, AU, or moderate-to-severe AA, 58% had SALT scores of 50% or better after receiving 5 mg tofacitinib twice daily for 4–18 months. Patients with AA improved more than those with AT or universalis. There were no severe adverse effects although nearly a third of patients developed upper respiratory tract infections.[12] In another uncontrolled study by Craiglow et al. of 13 patients with AA, totalis, or universalis, 9 (70%) patients achieved full regrowth and there were no serious adverse effects although patients experienced headaches, upper respiratory infections, and mild increases in liver transaminase levels.[13]

Other jakinibs such as ruxolitinib and baricitinib [14] are being used for AA. In this pilot study by Mackay-wiggan et al., 9 of 12 patients (75%) treated with ruxolitinib showed significant scalp hair regrowth and improvement of AA with ruxolitinib.[15]

Recently, topical formulation of tofacitinib and ruxolitinib is available and is shown to have positive results. About 0.6% ruxolitinib cream used twice daily for 12 weeks in a case of refractory AU resulted in full eyebrow regrowth and also 10% of scalp hair regrowth.[16]

CONCLUSION

The immune pathways required for autoreactive T-cell activation in AA are not defined limiting clinical development of rational targeted therapies. There are only few studies in the literature showing the efficacy of tofacitinib and ruxolitinib in the treatment of AU.[12,16,17,18] There are no severe adverse reactions reported for the drug; till now, two of our patients had developed acneiform reactions. One of the shortcoming of the drug is a progression of disease/recurrence after stopping the drug as reported by few studies suggesting maintenance therapy for remission.[12,15] This is the first published case series of successful treatment with tofacitinib from India although the sample size was small. All our patients started with the drug responded dramatically with satisfactory regrowth of hair and arrest in disease progression. Currently, the patients are in follow-up period. Relapse of the disease following discontinuation of the drug has been reported by few studies as happened in one of our patients. Further larger clinical trials are needed to establish the safety profile, long-term side effects, and disease remission protocol.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, Moshell AN, Melton LJ., 3rd Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted county, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628–33. doi: 10.4065/70.7.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilhar A, Etzioni A, Paus R. Alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1515–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1103442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElwee KJ, Tobin DJ, Bystryn JC, King LE, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata: An autoimmune disease? Exp Dermatol. 1999;8:371–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1999.tb00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Steen P, Traupe H, Happle R, Boezeman J, Sträter R, Hamm H, et al. The genetic risk for alopecia areata in first degree relatives of severely affected patients. An estimate. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:373–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biran R, Zlotogorski A, Ramot Y. The genetics of alopecia areata: New approaches, new findings, new treatments. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;78:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang H, Wu WY, Lo BK, Yu M, Leung G, Shapiro J, et al. Hair follicles from alopecia areata patients exhibit alterations in immune privilege-associated gene expression in advance of hair loss. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2677–80. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, Cerise JE, Higgins CA, Gong W, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20:1043–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delamere FM, Sladden MM, Dobbins HM, Leonardi-Bee J. Interventions for alopecia areata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16:CD004413. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004413.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harel S, Higgins CA, Cerise JE, Dai Z, Chen JC, Clynes R, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling promotes hair growth. Sci Adv. 2015;1:e1500973. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mease PJ, Hall S, FitzGerald O, van der Heijde D, Merola JF, Avila-Zapata F, et al. OP0216 efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, an oral janus kinase inhibitor, or adalimumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (CSDMARDS): A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(Suppl 2):141–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craiglow BG, King BA. Killing two birds with one stone: Oral tofacitinib reverses alopecia universalis in a patient with plaque psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2988–90. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: A study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, Cerise JE, Ramot Y, Berkun Y, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:351–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackay-Wiggan J, Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, Clark C, Ulerio G, et al. Oral ruxolitinib induces hair regrowth in patients with moderate-to-severe alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89790. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craiglow BG, Tavares D, King BA. Topical ruxolitinib for the treatment of alopecia universalis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:490–1. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta AK, Carviel JL, Abramovits W. Efficacy of tofacitinib in treatment of alopecia universalis in two patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1373–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, Li S, Shankar G, Urban JR, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89776. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]