Abstract

Background:

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune characterized by nonscarring loss of scalp and/or body hairs. Topical PUVA has been reported to have good effect in AA. The modification of topical PUVA which we call, “Turban PUVA-sol,” is a method of localized immunotherapy using psoralen solution followed by sun exposure.

Aims:

We aim to study the therapeutic role and side effect profile of turban PUVA in the treatment of advanced and refractory AA.

Methodology:

Fifteen consecutive patients of alopecia subtotalis (at least 70% of scalp hair loss), totalis, and universalis, attending the dermatology outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital in eastern India were subjected to “Turban PUVA-sol” after duly signed consent. Alternate day therapy was given.

Results:

At the end of 10 months of study, 2 (13%) out of fifteen patients were lost to follow-up for some unknown reasons. The severity of alopecia tool scores showed a significant (P = 0.0002) decrease posttreatment. Correlation between the severity of alopecia and grade of improvement showed a rho value of −0.453. In the remaining thirteen patients, using physician global assessment (PGA), 4 (26%) showed good response, 4 (26%) showed moderate response, 3 showed mild (20%) response, and 2 patients (13%) showed negligible response. Three out of four patients who showed good improvement in PGA showed more than 80% of new hair growth. Side effects are minimal with some patients complaining of mild irritation and scaling.

Conclusion:

We found topical Turban PUVAsol to be a very cost-effective and safe treatment option for AA.

Key words: Alopecia areata, alopecia subtotalis, alopecia totalis, photochemotherapy, psoralen, severity of alopecia tool score, turban PUVAsol

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by nonscarring loss of scalp and/or body hairs.[1] Not many successful treatment options are available especially in advanced cases of scalp AA which has quite a poor prognosis.[2] Phototherapy is a well-recognized method in treating many T–cell-mediated disease including psoriasis, vitiligo, and AA. When sunlight (solar) is used as a source of UV rays, this modality of therapy is known as PUVAsol.[3] Avoiding oral psoralen and using it topically over scalp in a turban fashion creates a modified modality of therapy reported as Turban PUVAsol. There had been a few publications in the world literature where it was shown to be effective and safe in AA.[4,5,6] The facilities of phototherapy unit targeting the scalp are expensive and largely unavailable in a developing country like India. If this modified form localized immunotherapy, which we refer from here on as Turban PUVAsol, is found effective and safe then it would give a very simple, inexpensive, treatment options in an otherwise unrewarding condition of advanced AA.

Aim

This study aims to study the therapeutic role and side effect profile of turban PUVAsol in the treatment of advanced and refractory cases of AA.

METHODOLOGY

Consecutive patients of alopecia subtotalis (at least 70% of scalp hair loss), totalis, and universalis refractory to at least two forms of conventional therapies, attending the dermatology outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital in eastern India were subjected to Turban PUVAsol after duly signed consent. The patients recruited were treated by at least one localized (topical steroids, intralesional steroids, topical minoxidil, topical calcineurin inhibitors) and one systemic agent (systemic steroids, cyclosporine, methotrexate, or any other immunosuppressive drug) and were refractory to those treatments.

Patients were asked to mix 1 ml of 8-methoxypsoralen solutions in 2 liters of water. A cotton towel of sufficient length was dipped and soaked in the prepared solution. After wringing out the excess solution, the towel was wrapped around the patient's head like a turban so as to cover the alopecia zone. After keeping the solution soaked turban for 30 minutes, sunlight exposure was given preferably in a time range of 10.00 am to 12:00 noon, in a graded fashion starting with a lower exposure time and gradually increasing the duration but keeping the maximum limit of sun exposure up to 15 min after which no further increment was done. Alternate day therapy (3 days/week) was given with an advice of use of sunscreen over other parts of the body. Patients were assessed at monthly intervals for improvement and possible side effects. Even after the complete course of treatment, we the patients for follow-up for 6-month post-treatment. Patients who showed minimal response or no response even after 3 months of treatment were described as failure and were taken off the treatment.

RESULTS

At the end of recruitment, fifteen patients were included in the study who had at least 70% involvement of the scalp with no response to treatment with two modalities of standard therapeutics. These patients were explained regarding the study and the treatment procedure and were included in the study after duly signing an informed consent.

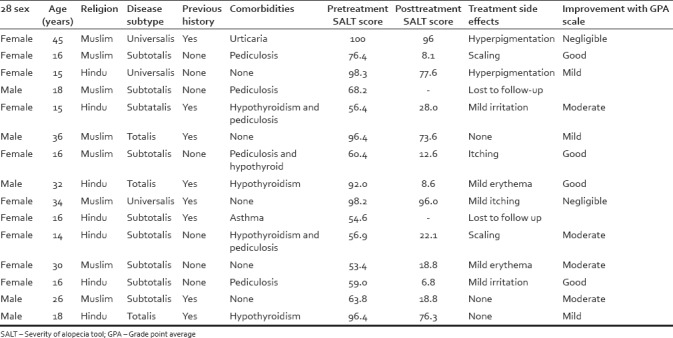

Of these 15 patients, 10 were females and 5 were males. Age distribution varied from 14 to 45 years, but majority of our patients were adolescent and young adults. Three patients were alopecia universalis, three more were alopecia totalis, and nine were subtotalis. Five patients had apparently no comorbidities; others had some comorbidities such as hypothyroid, pediculosis, urticaria, and asthma. Hypothyroid is a known comorbidity of AA and was found in 5 (33%) of our patients. However, an unusual high association of alopecia subtotalis and pediculosis was observed in our group of patients (6 out of 9 patients) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinicoepidemiological data of the patients

Two (13%) patients were lost to follow-up for some unknown reason. For the remaining thirteen patients, using physician global assessment (PGA), 4 (26%) showed good response, 4 (26%) moderate response, three mild (20%) response, and two patient (13%) showed negligible response. Three out of four patients who showed good improvement in PGA showed more than 80% of new hair growth. Side effects were minimal with some patients complaining of mild irritation, erythema, hyperpigmentation, and scaling [Table 1].

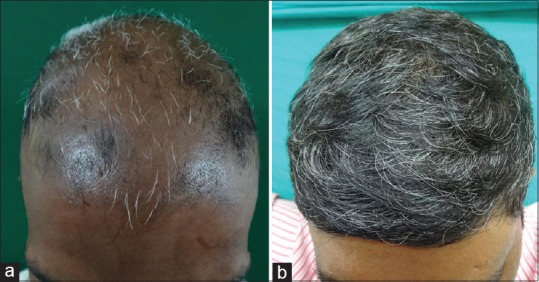

Patients showed good improvement in 3–6 months. We discontinued the treatment after 3 months, in the two patients who showed no response at all even after 3 months of therapy and shifted them to other conventional modalities of treatment [Figures 1–3].

Figure 1.

15 year old female patient with alopecia subtotalis (a) Before Turban PUVAsol. (b) After Turban PUVAsol

Figure 3.

32 year old male patient with alopecia totalis (a) Before Turban PUVAsol. (b) After Turban PUVAsol

Figure 2.

Alopecia subtotalis (a) Before Turban PUVAsol. (b) After Turban PUVAsol

We followed the patients for another 6-month posttreatment; efficacy was found to be long-term in six out of the eight patients who showed moderate-to-good improvement. Two patients showed small patches of recurrence of AA, which were treated with intralesional corticosteroids with good response.

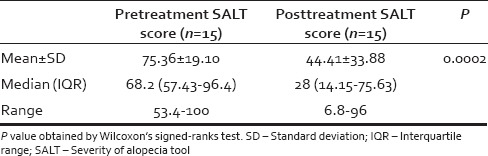

Modified intention to treat strategy was used during statistical analysis, and the last observation was carried forward in the two patients who were lost to follow-up. Pretreatment severity of alopecia tool (SALT) scores showed a mean value of 75.36 ± 19.10 and post-treatment SALT scores showed a decreased value of the mean to 44.41 ± 33.88. This decrease was statistically significant (P = 0.0002) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Pre- and post-treatment severity of alopecia tool scores of alopecia patients

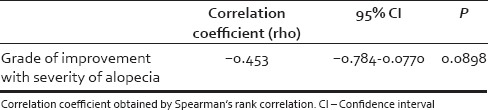

Spearman's rank correlation showed a rho value of −0.453 (95% confidence interval = −0.784 to + 0.0770), that is a negative correlation between the severity of alopecia and the grade of improvement of alopecia after treatment. Alopecia was graded as 1 = subtotalis, 2 = totalis, 3 = universalis and grade of improvement was scaled as 0 = no improvement, 1 = mild improvement, 2 = moderate improvement, 3 = very good improvement [Table 3].

Table 3.

Correlation between grade of improvement of alopecia with the severity of alopecia

DISCUSSION

AA is a nonscarring immune-mediated alopecia with a relapsing course, having a 1.7% lifetime risk. Characterized by patchy or total loss of hair from any part of body, it is the 3rd most common form of hair loss after AGA and telogen effluvium. Erythema may or may not be present. Immunohistochemical studies in human beings and animal models have demonstrated a perifollicular accumulation of dendritic cells plus CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and isolated polymorphonuclear cells.[1] British Association of dermatologist guidelines for the management of AA postulated several treatment options AA. Few worth mentioning treatment options are corticosteroids (topical, intralesional or systemic), contact immunotherapy, minoxidil, dithranol, calcineurin inhibitors, phototherapy, immunosuppressives, and biologics such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Miscellaneous treatment options not supported by randomized controlled trial are sulfasalazine, methotrexate, isoprinosine, LASER therapy, aromatherapy, and hypnotherapy.[7] Our procedure of “ Turban PUVASOL” is a modification of the conventional phototherapy which uses UV radiation and psoralen. Phototherapy has been traditionally used for treating T-cell-linked disorders such as psoriasis, vitiligo, severe eczema, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. When phototherapy combines with an exogenous photosensitizer agent so as to augment its benefits, it is known as photochemotherapy and the most commonly used photosensitizer are psoralens. Psoralens are naturally occurring tricyclic furocoumarin compounds, and when used in combination with UVA exposure is popularly known as PUVA. Although several compounds such as trimethoxy, octamethoxy, pentamethoxy psoralens are available, we have used octa variant which rapidly penetrates the skin and can be detected in the urine after 4 h. PUVA sol is the concept of using psoralen with sunlight as a source of UVA radiation. It is a good cost effective choice in developing countries with poor infrastructure, having a better compliance as long distance travel is not required.[2] Pai and Srinivas described bath suit PUVA method and our turban PUVA can be considered a variation of the same.[8] Weissmann et al. first reported the use of PUVA with artificial UV light source in AA although Rollier and Warcewski in the year 1974 were the first to use 8-methoxypsoralen and natural sunlight to induce hair growth in a single patient of AA.[3,9] Behrens et al. in 2001 got promising results in six patients of AA while Broniarczyk-Dyla et al. in 2006 postulated turban PUVA as a well-tolerated treatment option particularly for patchy and subtotalis rather than higher variants.[10,11] However, the reports of use of topical PUVAsol in AA were few and mostly case reports, and a larger trial was necessary to evaluate the role of this simple and unique method in refractory cases of advanced AA. Our study proved that turban PUVA sol is a safe and effective option for advanced and refractory AA, especially of developing nations where expensive biologics or specialized phototherapy units are unavailable or unaffordable. The significant decrease in the SALT scores posttreatment in our study shows objectively that turban PUVA is indeed effective. We found that greater is the severity of alopecia, lesser is the improvement.

CONCLUSION

We found topical turban PUVA sol a very cheap, effective, and safe treatment option which showed dramatic response to many treatment-resistant cases of AA. Considerable therapeutic benefit was noticed and assessed by clinically growth of new hairs. Six-month follow-up showed that efficacy is long-term in most patients. However, further studies are required especially with a control group to find out the extent of risk and benefits.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cho HH, Jo SJ, Paik SH, Jeon HC, Kim KH, Eun HC, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors in early-onset alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:799–802. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.7.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vañó-Galván S, Fernández-Crehuet P, Grimalt R, Garcia-Hernandez MJ, Rodrigues-Barata R, Arias-Santiago S, et al. Alopecia areata totalis and universalis: A multicenter review of 132 patients in Spain. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:550–6. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weissmann I, Hofmann C, Wagner G, Plewig G, Braun-Falco O. PUVA-therapy for alopecia areata. An investigative study. Arch Dermatol Res. 1978;262:333–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00447370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sornakumar L, Sekar CS, Srinivas C. Turban PUVASOL: An effective treatment in alopecia totalis. Int J Trichology. 2010;2:106–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.77520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pai SB, Shetty S. Guidelines for bath PUVA, bathing suit PUVA and soak PUVA. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:559–67. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.168336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kc S, Karn D. Practical aspects in topical PUVAsol in dermatology: An experience in a teaching hospital. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2014;12:306–7. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v12i4.13741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messenger AG, McKillop J, Farrant P, McDonagh AJ, Sladden M. British association of dermatologists' guidelines for the management of alopecia areata 2012. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:916–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pai S, Srinivas CR. Bathing suit delivery of 8-methoxypsoralen for psoriasis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:576–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb02901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rollier R, Warcewski Z. Le traitement de la pelade par la meladinine. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1974;81:97. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behrens-Williams SC, Leiter U, Schiener R, Weidmann M, Peter RU, Kerscher M, et al. The PUVA-turban as a new option of applying a dilute psoralen solution selectively to the scalp of patients with alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:248–52. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.110060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broniarczyk-Dyla G, Wawrzycka-Kaflik A, Dubla-Berner M, Prusinska-Bratos M. Effects of psoralen-UV-A-turban in alopecia areata. Skinmed. 2006;5:64–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2006.04240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]