Abstract

Background:

Alopecia areata (AA) is a T-lymphocyte-mediated disease that results in alopecia plaques or diffuses alopecia on the scalp and body. Etiologic factors include genetic and autoimmune susceptibility. Treatment modalities are usually considered according to the extent of hair loss and the patient's age. Since there is no approved treatment by the US Food and Drug Administration, treatment options and combinations available are off-label. Patients with extensive AA (including totalis and universalis) have a low rate of spontaneous remission and poor treatment response. Extensive AA is usually associated with severe emotional distress, social discomfort, bullying, and other psychological problems for the child and family. In this context, the need for new therapeutic schemes is clear.

Materials and Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed five patients (aged 2–17 years) with extensive and refractory AA who were treated with mesalazine associated or not with oral prednisolone and topical betamethasone/minoxidil.

Results:

We observed complete growth of terminal hair in all patients. No patient had abnormal laboratory results or manifested drug side effects.

Conclusions:

In extensive and refractory AA cases, the topical treatment combined with mesalazine may provide excellent results, reducing the need for extended oral corticosteroids courses. Besides that, mesalazine seems to minimize relapses on discontinuation of oral steroids. Controlled studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of this combination.

Key words: Alopecia areata, aminosalicylates, mesalazine, sulfasalazine

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) affects both adults and children with an estimated prevalence of 0.1%–0.2% in the general population and lifetime risk of 1.7%. Its pathology is classified based on the extent (plaques, total, and universal) or pattern (plaques, ophiasic, inverse ophiasic, reticular, or diffuse).[1] AA is a T-lymphocyte-mediated autoimmune disease that results in patches of hair loss on the scalp (AA plaques and total AA) or loss of all body hair (universal alopecia).[2] Etiologic factors include genetic and autoimmune susceptibility.[1,2] The treatment of AA includes topical (steroids, minoxidil, anthralin, diphencyprone, and capsaicin) and systemic (corticosteroids, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and sulfasalazine) drugs.[3] Since there is no approved treatment by the US Food and Drug Administration, all reported schemes are off-label.[4] Sulfasalazine provided good results and has been used as an alternative for refractory cases,[3,5,6,7] with hair regrowth ranging from 23% to 68%.[3,4,5,6,7] Sulfasalazine is a prodrug composed of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) linked to sulfapyridine by an azo ring. While 5-ASA is responsible for the efficacy of sulfasalazine, sulfapyridine is responsible for most of its adverse events as headache, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, that occur in 10%–45% of patients.[3,6,8] Sulfasalazine has been used for ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, rheumatoid arthritis lupus, and psoriasis.[8,9] Mesalazine (delayed-release 5-ASA), which does not contain sulfapyridine, is better tolerated than sulfasalazine.[8,9] It is a used for inflammatory bowel diseases at a dose of 30–50 mg/kg/day in children.[9] 5-ASA has both immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive functions, including inhibition of interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, tumor necrosis factor-α, lipoxygenase pathway, prostaglandin E2 release, inhibition of cellular chemotaxis, and inhibition of antibody production.[3,6] Here, we describe a series of pediatric cases where mesalazine associated or not with oral corticosteroid and topical betamethasone/minoxidil led to excellent results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

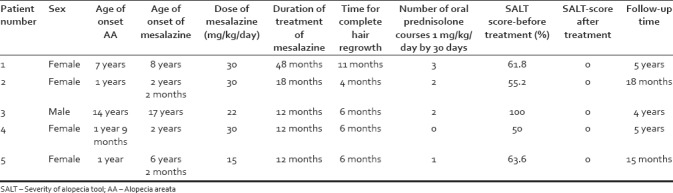

We retrospectively analyzed four girls and a boy aged 2–17 years old diagnosed with extensive AA who were refractory to multiple treatments (included 0.05% capillary betamethasone dipropionate, 5% minoxidil capillary lotion, and oral corticosteroid course) between 2012 and 2017, with a mean duration of AA of 25.4 months. Because all patients were typical cases of AA, they were diagnosed clinically (physical examination and/or dermatoscopy), and no anatomopathological study was performed. The Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, which quantifies hair loss percentage assessed severity. Scores 0 and 100 indicated no capillary loss and total loss, respectively.[10] Topical treatment (0.05% capillary betamethasone dipropionate and 2%–5% minoxidil capillary lotion) was maintained and mesalazine was added orally at 15–30 mg/kg/day in two divided doses. A few additional courses of oral prednisolone during treatment are detailed in Table 1. Blood counts, glucose-6-phosphatase dehydrogenase, hepatic and renal function, blood glucose, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and antithyroid peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO) were normal in all except patient 3. At the outpatient follow-up, blood counts and hepatic and renal function examinations were repeated monthly and were normal in all cases. Photographic control was performed before starting mesalazine and monthly thereafter. The duration of treatment including mesalazine ranged from 12 to 48 months. Sex, age of onset of AA, detailed mesalazine treatment information, SALT score before and after the treatment, and follow-up time are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients treated with mesalazine - Pediatric Dermatology Unit, Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012-2017

Clinical cases

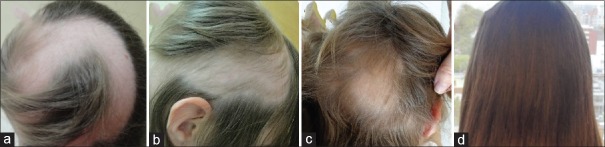

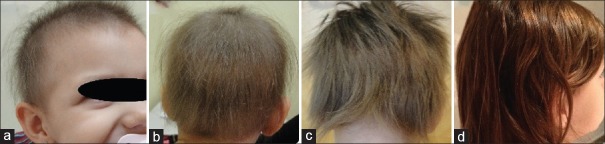

Patient 1 had a history of inverse psoriasis on the labia majora and perineum. In the first evaluation, she presented alopecia in the frontoparietal area [Figure 1a]. Hair loss stabilized 30 days after mesalazine onset [Figure 1b]. In the following years, she had three episodes of active hair loss [Figure 1c] and used oral prednisolone during these periods. Follow-up showed no further loss episodes after treatment discontinuation [Figure 1d]. Patient 2 presented alopecia plaques in the frontal, vertex, and occipital regions and positive traction test [Figure 2a and b]. She had two episodes of active hair loss and used oral prednisolone during these episodes. Mesalazine treatment was interrupted because of lost to follow-up [Figure 2c and d]. Patient 3, who had hypothyroidism, reported that AA worsened, with evolution to universal AA and 100% SALT score, 3 months prior [Figure 3a]. He had been on treatment with levothyroxine for 3 years. Blood tests were normal except an anti-TPO of 682 (up to 35 IU/ml). He underwent mesalazine treatment, resulting in partial and total regrowth of scalp hair after 3 [Figure 3b] and 6 months, respectively. He received two cycles of oral prednisolone for the purpose of eyebrow growth. Mesalazine was continued for 1 year with total regrowth of scalp hair and partial regrowth in eyebrows and eyelashes [Figure 3c and d]. Patient 4 consulted for diffuse and sudden hair loss. She had diffuse alopecia on the scalp, rarefaction of the eyebrows, and dermatoscopy showing exclamation-point hairs. We started the treatment with 0.05% capillary betamethasone dipropionate and 2% minoxidil capillary lotion. After 60 days, she continued with substantial rarefaction; their parents decided not to use oral prednisolone and mesalazine was administered [Figure 4a]. Ophiasic alopecia appeared 1 month after mesalazine onset. Scalp hair regrowth was evident 3 months after mesalazine onset [Figure 4b] and complete after 6 months [Figure 4c]. She used mesalazine for 1 year [Figure 4d]. Patient 5 had alopecia plaques in the fronto-parieto-occipital and positive traction test [Figure 5a and b] evolving throughout 5 years. Hence, we decided to initiate a course of oral prednisolone along with mesalazine at the beginning of the treatment. After 6 months of treatment, she had complete hair regrowth in the scalp [Figure 5c and d]. None of the cases presented relapses on discontinuation of oral prednisolone.

Figure 1.

Patients 1: (a) Alopecia prior to mesalazine; (b) 30 days after mesalazine; (c) relapse after 6 months; (d) end of the treatment

Figure 2.

Patients 2: (a and b) Alopecia before mesalazine; (c and d) 4 months after mesalazine

Figure 3.

Patient 3: (a) Alopecia before mesalazine; (b) 3 months after mesalazine; (c and d) total regrowth after 1 year

Figure 4.

Patient 4: (a) Alopecia before mesalazine; (b) partial regrowth 3 months after mesalazine; (c) total regrowth 6 months after mesalazine; (d) 1 year after mesalazine

Figure 5.

Patient 5: (a and b) Alopecia before treatment; (c and d) 6 months after mesalazine

DISCUSSION

Studies on mesalazine as treatment for AA have not been reported before as far as we know. In this series of cases, we present five pediatric patients with AA with significant hair loss who had a satisfactory hair regrowth response when mesalazine was added to the treatment as a repurposed drug. Although relative contribution of each agent is still unclear (oral corticosteroid in short term, topical corticosteroid, minoxidil, and mesalazine), mesalazine seems to have been helpful in reducing the oral corticosteroids courses and minimizing relapses on discontinuation of oral steroids. Mesalazine was well tolerated and controlled the emergence of new alopecic areas. These findings are in line with Bakar and Gurbuz [5] report that a similar drug (sulfasalazine) sustained the steroid-induced hair growth.

Despite the limitations of a retrospective analysis and a small sample, our results indicate that mesalazine may assist in the treatment of patients with severe or refractory AA when used as adjunctive therapy. In addition, it is a safe and painless therapeutic option, which facilitates administration to pediatric patients. Hematological and hepatic laboratory monitoring during treatment with mesalazine is recommended, as well as dose fractioning twice per day.[9] Controlled studies are needed to ensure its effectiveness.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mukherjee N, Burkhart CN, Morrell DS. Treatment of alopecia areata in children. Pediatr Ann. 2009;38:388–95. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20090511-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update: Part I. Clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:177–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update: Part II. Treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hordinsky MK. Alopecia areata: The clinical situation. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2018;19:S9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakar O, Gurbuz O. Is there a role for sulfasalazine in the treatment of alopecia areata? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:703–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rashidi T, Mahd AA. Treatment of persistent alopecia areata with sulfasalazine. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:850–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aghaei S. An uncontrolled, open label study of sulfasalazine in severe alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:611–3. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiersma H, Escher JC, Dilger K, Trenk D, Benninga MA, van Boxtel CJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of mesalazine pellets in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:626–31. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karagozian R, Burakoff R. The role of mesalamine in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3:893–903. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen EA, Hordinsky MK, Price VH, Roberts JL, Shapiro J, Canfield D, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines – Part II. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:440–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]