Abstract

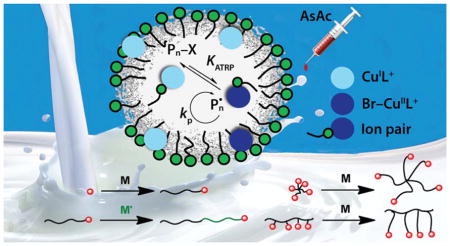

It was recently reported that copper catalysts used in atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) can combine with anionic surfactants used in emulsion polymerization to form ion pairs. The ion pairs predominately reside at the surface of the monomer droplets, but they can also migrate inside the droplets and induce a controlled polymerization. This concept was applied to activator regenerated by electron transfer (ARGET) ATRP, with ascorbic acid as reducing agent. ATRP of n-butyl acrylate (BA) and n-butyl methacrylate (BMA) was carried out in miniemulsion using CuII/tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (TPMA) as catalyst, with several anionic surfactants forming the reactive ion-pair complexes. The amount and structure of surfactant controlled both the polymerization rate and the final particle size. Well-controlled polymers were prepared with catalyst loadings as low as 50 ppm, leaving only 300 ppb of Cu in the precipitated polymer. Efficient chain extension of a poly(BMA)-Br macroinitiator confirmed high retention of chain-end functionality. This procedure was exploited to prepare polymers with complex architectures such as block copolymers, star polymers, and molecular brushes.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Reversible-deactivation radical polymerizations (RDRPs) in heterogeneous media are characterized by good heat transfer, low environmental impact, low viscosity, and low toxicity,1 which are important advantages for commercial applications.2 Moreover, polymerization in dispersed media, including microemulsion, miniemulsion, emulsion, and dispersion, can be used to prepare nanoparticles with various morphologies (e.g. core–shell, microcapsules and multilayered particles) for specific applications in biomedical, pharmaceutical, drug delivery, or diagnostic areas.1,3–6

RDRPs provide well-defined polymers with low dispersity (Đ), limited amount of radical termination, and predetermined architecture and molecular weight (MW).7–9 The most often used RDRP methods are atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), reversible addition–fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization, and nitroxide-mediated polymerization (NMP), which have been successfully developed in both homogeneous and heterogeneous media.9–15 Moreover, heterogeneous systems additionally limit radical termination through radical segregation and compartmentalization.16–18 Despite the benefits offered by dispersed media, the vast majority of RDRPs are still performed in homogeneous systems.

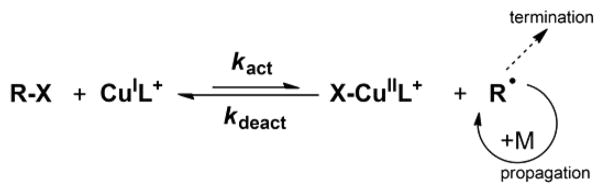

A promising technique for heterogeneous polymerization is ATRP, which is based on radical generation by an active catalyst, generally a copper–amine complex in its lower oxidation state, i.e., CuIL+ (Scheme 1).19 The CuIL+ complex activates an alkyl halide initiator (R–X) or dormant chain end (Pn–X), forming a propagating radical and a higher oxidation state deactivator complex X–CuIIL+. A small fraction of chains is active at one time and initiation can be fast; therefore, all chains grow homogeneously and termination reactions are minimized.20

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of ATRP

During the past decade, catalyst loading was reduced by the development of “low-ppm” ATRP techniques. These methods comprise activators regenerated by electron transfer (ARGET) ATRP,21,22 initiators for continuous activator regeneration (ICAR) ATRP,23 supplemental activator and reducing agent (SARA) ATRP,24–28 electrochemically mediated ATRP (eATRP),29–33 photoATRP,34,35 and mechanoATRP.36,37 Nevertheless, for some applications, residual catalyst should be removed, using column filtration, electrodeposition, or more complex methods, depending on the desired degree of purity.38–43

The biphasic nature of heterogeneous polymerizations can simplify catalyst removal. Indeed, in miniemulsion systems, the large surface area of the organic/water interface helps mass transport of the catalyst from the polymer particles to the aqueous phase, if a sufficiently hydrophilic catalyst is used. The catalyst, however, should be also sufficiently hydrophobic to enter the hydrophobic monomer droplets, where it starts and controls the miniemulsion polymerization.1,44

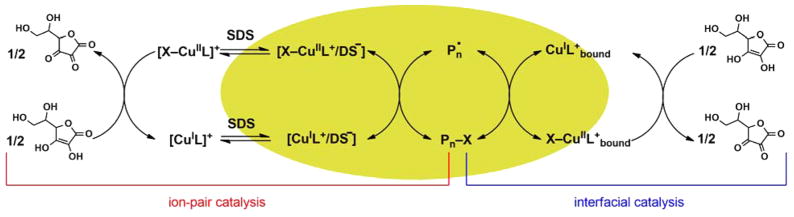

In this context, we recently developed a novel catalytic system for eATRP, based on a strongly hydrophilic complex, Br–CuIITPMA+. Despite its insoluble nature in n-butyl acrylate (BA), the catalyst enters hydrophobic BA droplets when combined with an anionic surfactant, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).45 The interaction between catalyst and SDS formed neutral ion pairs, Br–CuIITPMA+/DS−, that resided either at the surface or inside the BA droplets. This concept could be considered as a paradigm shift for miniemulsion ATRP, which previously required very hydrophobic catalysts that were predominately confined to the organic phase.46–50 With the Br–CuIITPMA+/SDS system, only ~1% of the catalyst was inside the hydrophobic droplets as ion pairs, 95% was bound at the monomer/water interface, and ~4% was in the aqueous phase. Therefore, such a combination of ion-pair and interfacial catalysis (cf. Scheme 2) allowed for the successful eATRP of BA. Relevant for industrial application, ≤1% of total Cu was detected inside the final latex after centrifugation.

Scheme 2.

Mechanism of Ion-Pair and Interfacial Catalysis in ARGET ATRP in Miniemulsion with Ascorbic Acid as Reducing Agent

In the present work, the concept of ion-pair and interfacial catalysis was exploited in miniemulsion ARGET ATRP of BA and n-butyl methacrylate (BMA), with ascorbic acid (AsAc) as reducing agent (Scheme 2). Several hydrophilic ligands and anionic surfactants were evaluated (Scheme 3). The effect of SDS concentration on particles size, polymerization kinetics, and degree of control was studied, providing some mechanistic insights. Cu concentration was reduced to minimize contamination in the final product. Both low and high degrees of polymerization (200–1200) were targeted. The livingness of the process was confirmed by chain-extending a poly(n-butyl methacrylate)–Br macroinitiator (PBMA-MI) with both acrylic and methacrylic monomers, confirming the high retention of chain-end functionality. Synthesis of polymers with complex architecture, such as stars and brushes, was successful.51

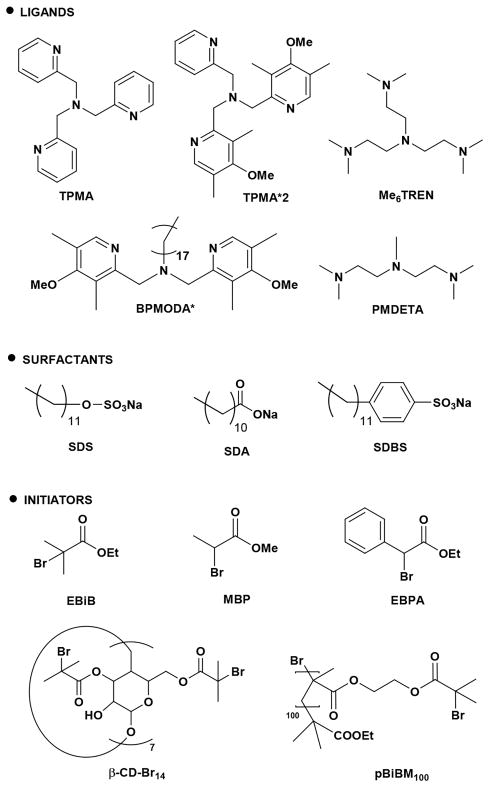

Scheme 3.

Chemical Structures of Copper Ligands, Surfactants, and Initiators Used in This Work

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effect of Ligand Structure on Miniemulsion ATRP of BA

Different copper complexes were tested in ARGET ATRP with 20 vol % BA in water, using ultrasonication to form a miniemulsion with the composition reported in Table 1. NaBr (0.1 M) was added to increase the stability of the Br–CuIIL+ deactivator, which could otherwise dissociate to CuIIL2+ + Br− in aqueous media.52,53 The appropriate amount of AsAc was injected dropwise during the first 3 min of the reaction, considering that reduction of all CuII requires [AsAc]/[CuII] = 0.5.46

Table 1.

Composition of Organic and Aqueous Phases in a Typical Miniemulsion ARGET ATRPa

| component | weight (g) | comments |

|---|---|---|

| organic phase | ||

| monomer | 1.79 | 20 vol % (18 wt %) |

| R–Xb,c | 0.0098 (EBiB), 0.0109 (EBPA) | [monomer]/[R–X] = 280/1 |

| hexadecane | 0.19 | 10.8 wt % to monomer |

| aqueous phase | ||

| water | 8 | deionized water |

| SDSc | 0.082 | 4.6 wt % to monomer |

| NaBr | 0.103 | [NaBr] = 0.1 Md |

| CuIIBr2 | 2.2 × 10−3 | 1 mMd |

| TPMAc | 2.4 × 10−3 | 1.1 mMd |

| AsAc | varied | cf. Tables 2–5 |

Conditions: T = 65 °C, Vtot = 10 mL. The miniemulsion was prepared by ultrasonication as described in the Supporting Information.

[R–X] was varied to target different degrees of polymerization (DPs).

Chemical structures of surfactants, initiators, and ligands are presented in Scheme 3.

With respect to the total volume.

The Cu complexes with pyridinic ligands, Br–CuIITPMA+ and Br–CuII(TPMA*2)+, provided well-controlled PBA with Đ ≈ 1.2 and experimental MW (Mn,app) close to theoretical values (Table 2, entries 1–3). The obtained latex was stable for several months, and particle size varied less than 15% before and after polymerizations, as measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS). Comparable results were obtained using either NaBr or Et4NBr as a source of Br− to stabilize Br–CuIITPMA+ (Table 2, entry 1 vs 2). Et4NBr, however, formed larger monomer droplets, indicating that Et4N+ can slightly destabilize latex formation.

Table 2.

Effect of Various Ligand–Surfactant Combinations in ARGET ATRP Miniemulsion Polymerization of BAa

| entry | ligand | surfactant | t (h) | conv (%) | kpapp b (h−1) | Mn,app (×10− 3) | Mn,th (×10−3) | Đ | dZc (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TPMA | SDS | 6 | 66 | 0.25 | 30.9 | 24.4 | 1.17 | 117 ± 2 |

| 2 | TPMAd | SDS | 5 | 70 | 0.31 | 24.1 | 25.5 | 1.14 | 152 ± 1 |

| 3 | TPMA*2 | SDS | 3 | 40 | 0.21 | 10.0 | 14.5 | 1.24 | 114 ± 1 |

| 4 | PMDETA | SDS | 2 | 79 | 1.42 | 38.5 | 28.8 | 5.02 | 161 ± 1 |

| 5 | Me6TREN | SDS | 1.1 | 89 | 2.21 | 32.4 | 32.2 | 2.65 | 152 ± 2 |

| 6 | TPMA | SDBS | 3 | 84 | 0.63 | 29.8 | 30.4 | 1.32 | 153 ± 1 |

| 7 | TPMA | SDS + SDAe | 5 | 74 | 0.31 | 27.4 | 27.0 | 1.25 | 273 ± 3 |

General conditions as in Table 1. [AsAc]/[CuII] = 0.5, AsAc injected dropwise at t = 0 h.

The slope of the ln([M]0/[M]) vs time plot.

Z-average particles diameter, measured by DLS.

Et4NBr replaced NaBr.

[SDS] = 4.6 wt % and [SDA] = 0.5 wt % relative to BA.

The polymerization rates were almost the same with Br–CuIITPMA+ and Br–CuII(TPMA*2)+, despite the much higher redox activity of the latter catalyst. On the other hand, the interactions between SDS and either Br–CuII(TPMA*2)+ or Br–CuIITPMA+ were similar.45 This indicates that the intrinsic catalyst activity, catalyst interaction with the surfactant, and the partitioning of the catalyst between the organic and aqueous phases are all important parameters.

Me6TREN and PMDETA were also tested as ligands under otherwise identical conditions. These aliphatic-amine ligands led to 6–9 times faster polymerizations than with TPMA, but poorly controlled (Table 2, entries 3 and 4). Similar poor control was previously observed in eATRP with Me6TREN and attributed to a much weaker interaction between SDS and Br–CuIIMe6TREN+ than with Br–CuIITPMA+. Moreover, previous electrochemical studies showed that the interaction between Cu/Me6TREN and SDS was stronger for CuI than CuII species. Abundant CuIMe6TREN+/DS− explains the faster polymerization, while scarce Br–CuIIMe6TREN+/DS− suggests that insufficient deactivator was present at the polymerization loci.45 In fact, GPC traces revealed a sharp peak followed by a broad signal at high MWs, indicating the presence of droplets with very low deactivator concentration (Figure S1).

Under homogeneous conditions, CuI/Me6TREN+ is 1 order of magnitude more reactive than CuI/TPMA+. Therefore, in miniemulsion the following strategies were attempted to slow down the reaction and improve control with CuIMe6TREN+: (i) reduce catalyst and/or ascorbic acid loadings, (ii) use of NaCl instead of NaBr, and (iii) replace the EBiB initiator by MBP, with a secondary less reactive alkyl structure.54 Nevertheless, all polymerizations were fast and polymers with high Đ were obtained (Table S1).

The CuIPMDETA+ catalyst is much less active than either CuIMe6TREN+ or CuITPMA+.55,56 Therefore, the poor control observed with Br–CuIIPMDETA+ suggests that the interaction of this complex with SDS is very weak. In conclusion, pyridinic ligands, such as TPMA, are better suited for miniemulsion ARGET ATRP due to the specific interactions between catalyst and surfactant, which enable both CuI and CuII species to enter the hydrophobic droplets and tune the polymerization process.

Effect of Structure and Amount of Surfactant on Miniemulsion ATRP of BA

Several anionic surfactants were evaluated to form ion-pair complexes (Scheme 3): SDS, sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (SDBS), and sodium dodecanoate (SDA).

SDBS provided a fast polymerization (Table 2, entry 6, and Figure S2), reaching 84% conversion in 3 h, but polymers with Đ = 1.32, higher than with SDS under identical conditions, were obtained. The higher polymerization rate and the decreased control may be caused by a weaker interaction between Br–CuIITPMA+ and SDBS, leading to a lower amount of the CuII species inside the droplets.

SDA alone could not stabilize the BA miniemulsion; therefore, a combination of SDS and SDA was tested (4.6 wt % SDS + 0.5 wt % SDA relative to BA, Table 2, entry 7, and Figure S2). The obtained miniemulsion was stable, but particle size increased to ca. 270 nm (almost twice larger than with other surfactants). Polymerization was slightly faster than with SDS alone, yielding polymers with Đ = 1.25 and suggesting the presence of a different CuI/CuII ratio. SDA seemed to slightly destabilize the system, while SDS ensured the effective interaction with the Cu complex. Therefore, SDA can be used in combination with SDS to tune the particle size but preserving most of the polymerization control and the latex stability.

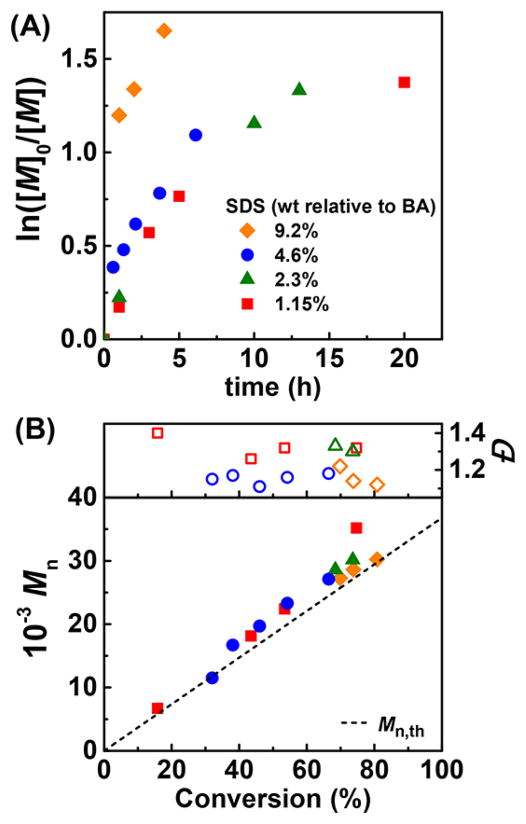

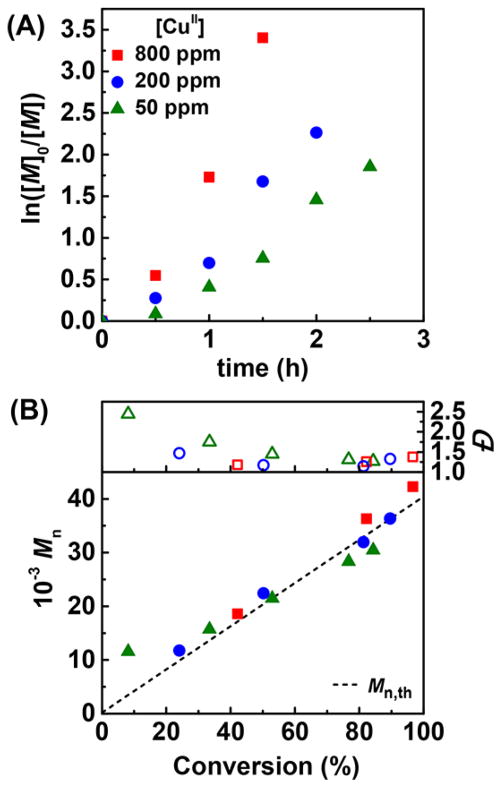

Finally, the amount of SDS was varied to change latex properties and polymerization kinetics (Table 3 and Figure 1). By lowering [SDS], decreased and first-order kinetics deviated from linearity. A controlled polymerization was even obtained with [SDS] as low as 1.15 wt % relative to monomer, which is below the critical micellar concentration (cmc) of the surfactant in the polymerization media (cmc = 8.9 mM for SDS in water + 0.1 M NaBr, T = 65 °C, which corresponds to 1.46 wt % relative to BA).45 Reducing [SDS] resulted in decreased control because less ion pairs were formed and less catalyst was bound to the surface of the droplets. Polymerization rate decreased because the droplets size increased, lowering the overall interfacial area, which slowed down the kinetics of mass transport. Nevertheless, the process remained controlled (Đ = 1.1–1.3) and the final latexes were stable, meaning that the amount of SDS can be varied to tune particles dimensions.

Table 3.

ARGET ATRP Miniemulsion Polymerization of BA with Different Amounts of SDSa

| entry | [SDS] (wt % rel to BA) | t (h) | conv (%) | b (h−1) | Mn,app (×10−3) | Mn,th (×10−3) | Đ | dZc (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.2 | 4 | 81 | 0.50 | 30.2 | 29.4 | 1.12 | 106 ± 2 |

| 2 | 4.6 | 6 | 66 | 0.25 | 30.9 | 24.4 | 1.17 | 117 ± 2 |

| 3 | 2.3 | 13 | 74 | 0.12 | 30.2 | 26.7 | 1.30 | 161 ± 1 |

| 4 | 1.15 | 20 | 74 | 0.16 | 35.2 | 27.2 | 1.32 | 207 ± 2 |

General conditions as in Table 1. [AsAc]/[CuII] = 0.5, AsAc injected dropwise at t = 0 h.

The linear slope of the ln([M]0/[M]) vs time in the first 10 h of polymerization.

Z-average particle diameter measured by DLS.

Figure 1.

ARGET miniemulsion ATRP of BA with different amounts of SDS (Table 3). (A) Semilogarithmic kinetic plot and (B) MW and Đ evolution vs conversion. [AsAc]/[CuII] = 0.5 added dropwise at t = 0 h. Other conditions as in Table 1.

Effect of Catalyst Loading on Miniemulsion ARGET ATRP of BA and BMA

The Br–CuIITPMA+ loading was reduced from 719, to 360, and to 144 ppm in a miniemulsion ARGET ATRP of BA and resulted in maintaining comparable polymerization rates (Table 4 and Figure S4). However, the dispersity increased with decreasing catalyst loading, in agreement with eq 1:7,57

Table 4.

ARGET ATRP Miniemulsion Polymerization of BA and BMA with Different Catalyst Loadings and Targeted DPa

| entry | [Br – CuIITPMA+] (ppm) | target DP | t (h) | conv (%) | b (h−1) | Mn,app (×10−3) | Mn,th (×10−3) | Đ | dZc (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| monomer = BA, R–X = EBiBd | |||||||||

| 1 | 719 | 280 | 6 | 66 | 0.25 | 24.4 | 30.9 | 1.17 | 117 ± 2 |

| 2 | 360 | 280 | 4 | 70 | 0.34 | 25.6 | 34.1 | 1.24 | 126 ± 2 |

| 3 | 144 | 280 | 4 | 71 | 0.31 | 26.1 | 36.7 | 1.65 | 121 ± 1 |

| 4 | 719 | 1000 | 20 | 71 | 0.07 | 91.6 | 101.8 | 1.25 | 126 ± 1 |

| monomer = BMA, R–X = EBPAe | |||||||||

| 5 | 800 | 280 | 1 | 82 | 1.60 | 36.3 | 32.9 | 1.26 | 135 ± 2 |

| 6 | 200 | 280 | 2 | 90 | 1.05 | 36.3 | 36.1 | 1.33 | 132 ± 3 |

| 7 | 50 | 280 | 2 | 77 | 0.72 | 31.6 | 30.9 | 1.31 | 139 ± 3 |

| 8 | 800 | 600 | 2.5 | 82 | 0.52 | 70.0 | 70.2 | 1.20 | 138 ± 2 |

| 9 | 800 | 1200 | 4 | 76 | 0.38 | 118.6 | 129.3 | 1.42 | 131 ± 2 |

| 10f | 800 | 280 | 6 | 92 | 0.35 | 34.5 | 36.9 | 1.18 | 193 ± 1 |

General conditions as in Table 1.

The slope of the ln([M]0/[M]) vs time plot.

Z-average particles diameter by DLS before polymerization.

[AsAc]/[CuII] = 0.5, AsAc injected dropwise at t = 0 h.

[AsAc]/[CuII] = 0.4 injected dropwise every 30 min, unless otherwise noted.

Br–CuIIBPMODA*+ was used as catalyst; [AsAc]/[CuII] = 0.5 injected at t = 0 h.

| (1) |

where kp is the propagation rate constant, kdeact is the deactivation rate constant, and p is conversion.

Control over BA polymerization was lost when 144 ppm of catalyst were used, which resulted in polymers with Đ = 1.65. Conversely, 360 ppm of catalyst ensured a well-controlled polymerization, even if, based on previous analysis, less than 10 ppm of copper species were present inside the monomer droplets under these conditions.45

ARGET ATRP of BMA was similar to BA polymerization. In fact, Br–CuIITPMA+ is poorly soluble in either BA or BMA (Figure S5), and therefore it entered monomer droplets only when paired with SDS.

ARGET ATRP of BMA required careful selection of the initiator: tertiary alkyl halides, such as EBiB, are less efficient initiators for methacrylates due to the penultimate unit effect.58 Indeed, with EBiB polymerization was slow resulting in polymers with Đ = 1.35 (Figure S6). Instead, ethyl 2-bromophenylacetate (EBPA), which is much more reactive than EBiB,59,60 provided a well-controlled process, reaching 34% conversion in 2 h and polymers with Đ = 1.13 (Table S2).

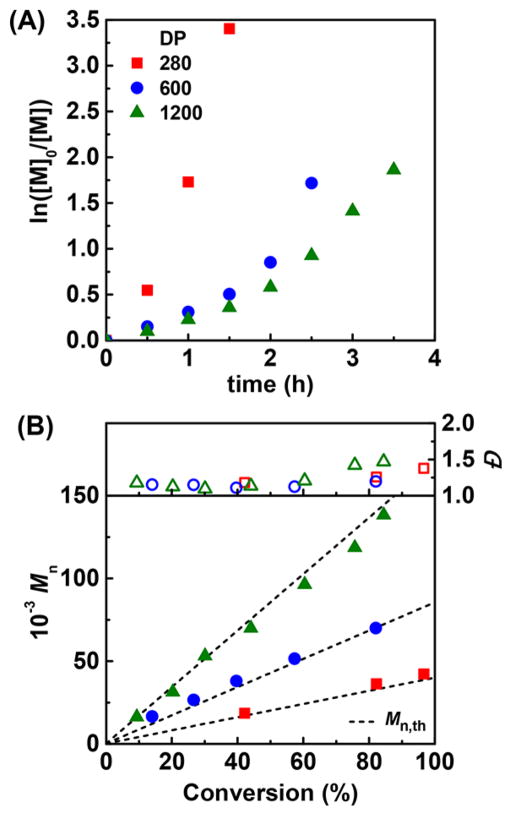

Polymerization stopped after 2 h, suggesting that the initial addition of AsAc ([AsAc]/[Br–CuIITPMA+] = 0.5) did not provide continuous regeneration of the active catalyst. Hence, the feeding of AsAc was optimized as described in the Supporting Information (Table S2 and Figure S8); a fast and well-controlled polymerization was obtained by simply injecting 0.4 equivalents of AsAc with respect to initial Br–CuIITPMA+, at t = 0 h and then subsequently every 30 min. 82% conversion in 1 h and polymers with Đ = 1.26 were obtained, with good agreement between experimental and theoretical MWs (Table 4, entry 5, and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Miniemulsion ARGET ATRP of BMA with various catalyst loadings. (A) Semilogarithmic kinetic plot and (B) MW and Đ evolution vs monomer conversion. [AsAc]/[CuII] = 0.4, injected dropwise every 30 min. Other reaction conditions are listed in Table 1.

Catalyst loading was successfully reduced from 800 to 50 ppm in ARGET ATRP of BMA (Table 4, entries 5–7). Polymerization rate (Rp) decreased with decreasing amount of Cu, exhibiting a good proportionality between Rp and the square root of [Br–CuIITPMA+], as predicted from eq 2:61

| (2) |

where kred is the reduction rate constant of Br–CuIITPMA+ and kt is the termination rate constant. 50 ppm of Br–CuIITPMA+, corresponding to 6.25 × 10−5 M, provided 77% conversion in 2 h with a final polymer with Đ = 1.31. However, Đ was higher during the first hour due to the slow ATRP deactivation with very low catalyst loadings (Figure 2). The much lower propagation rate constant, kp, of BMA than of BA permitted good control and low dispersity with few ppm of catalyst (cf. eq 1).62

Interestingly, the polymerization rate of BMA varied with initial [CuII], while the polymerization rate of BA did not. This is likely due to the different extent of radical termination in the two systems. The BMA system, with high ATRP activity and lower kp, was characterized by higher radical concentration, which increased the extent of radical termination. Therefore, a large portion of CuI catalyst was regenerated, and the kinetics agreed with eq 2. In the BA system, on the contrary, radical concentration was lower and termination was almost negligible. In this case, addition of AsAc established a fixed [CuI]/[CuII] ratio, so that the kinetics did not depend on [CuII]. (Note that a constant [AsAc]/[CuII] was used in each case.)

ICP-MS measurements of the precipitated PBMA revealed residual copper contents as low as 4.5, 1.6, and 0.3 ppm, with initial catalyst loadings of respectively 800, 200, and 50 ppm (over the total amount of monomer). Less than 1% of the initial copper content remained in the final polymer after precipitation. Metal contamination in the ppb range makes the polymer suitable for some applications without any purification procedure.63

For comparison, ARGET ATRP of BMA in miniemulsion was carried out with a traditionally used hydrophobic complex (Table 4, entry 10, and Figure S7), namely BPMODA*, which was specifically designed to form a highly active and hydrophobic copper catalyst.49 BPMODA* was prepared as described in the Supporting Information. Under the same conditions used for Cu/TPMA, Cu/BPMODA* gave well-controlled polymers, but particles size was 80% larger, suggesting potential destabilization of the droplets’ surface.43 Starting from 800 ppm of Br–CuIIBPMODA*+, ICP-MS measurements determined 45 ppm of residual copper in the precipitated polymer, 10 times higher than with Br–CuIITPMA+/SDS.

Effect of Targeted DP on Miniemulsion ATRP of BA and BMA

Higher degrees of polymerization were targeted by lowering initiator concentration. PBA with DP > 700, Đ = 1.25, and good agreement between theoretical and experimental MWs was obtained. Polymerization rate decreased for lower [R–X], as expected from eq 2, due to lower amount of generated radicals (Table 4, entry 4).61

High-MW PBMA was obtained when targeting DP = 600 and 1200 (Table 4, entries 8 and 9). Once again, polymerization rates were proportional to [R–X]. By switching from targeted DP = 280 to 600, Đ diminished from 1.25 to 1.20, in agreement with eq 1. However, Đ increased to 1.42 for DP = 1200 (Figure 3A), possibly due to the high viscosity in the polymerizing droplets. An increase of viscosity, besides slowing down termination events, can hamper radical deactivation by the small amount of CuII present inside the droplets. High viscosity can be related to the “autoacceleration” of the polymerization after 2 h (Figure 3A), which was concomitant with the increase in dispersity (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Miniemulsion ARGET of BMA with different target D with different target DPs (280, 600 and 1200). (A) Kinetic plot and (B) MW and Đ vs monomer conversion. [AsAc]/[CuII] = 0.5. Other reaction conditions listed in Table 1.

Chain Extension Experiments

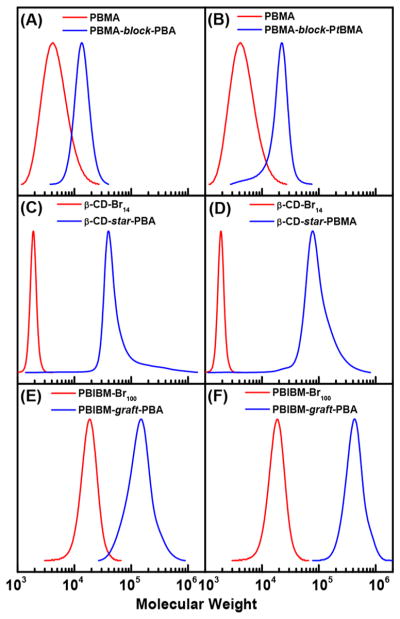

To test chain-end fidelity of the obtained polymers, a PBMA-MI was prepared by miniemulsion ARGET ATRP with Br–CuIITPMA+/SDS (see details in the Supporting Information). After purification, the macroinitiator had Mn,app = 4000 and Đ = 1.31 (Figure S10). Chain extension polymerizations were performed with both BA (Table 5, entry 1) and tert-butyl methacrylate (tBMA, Table 5, entry 2). Figures 4A and 4B show a clean shift of MWs in both cases, with monomodal MW distributions, confirming the high retention of chain-end functionality in the first block. The second block was also well-controlled, with Đ2 = 1.34 for tBMA and Đ2 = 1.15 for BA, calculated as Đ − 1 = w12(Đ1 − 1) + w22(Đ2 − 1), where w1 and w2 are the weight fractions of the first and second block, respectively.64 Thus, PBMA-MI was successfully chain-extended with both methacrylates and acrylates. High chain-end fidelity, indicating well-controlled polymerizations, motivated the synthesis of more complex structures by miniemulsion ARGET ATRP, such as star and brush-like polymers.

Table 5.

Preparation of Polymers with Complex Structures by ARGET ATRP in Miniemulsiona

| entry | initiator | polymer | t (h) | conv (%) | b (h−1) | Mn,app (×10−3) | Mn,th (×10−3) | Đ | dZc (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1d | PBMA-Br | PBMA-block-PBA | 2 | 30 | 0.20 | 13.0 | 11.7 | 1.10 | 118 ± 1 |

| 2e | PBMA-Br | PBMA-block-PtBMA | 1 | 30 | 0.35 | 16.1 | 12.6 | 1.19 | 119 ± 1 |

| 3e | β-CD-Br14 | β-CD-star-PBA | 2 | 73 | 0.70 | 47.7 | 65.7 | 1.39 | 118 ± 2 |

| 4e | β-CD-Br14 | β-CD-star-PBMA | 2 | 76 | 0.95 | 82.2 | 78.1 | 1.54 | 138 ± 2 |

| 5f | PBiBM100 | PBiBM100-graft-PBA | 4 | 94 | 0.44 | 357 | 125 | 1.29 | 194 ± 2 |

| 6f | PBiBM100 | PBiBM100-graft-PBA | 7 | 57 | 0.15 | 775 | 347 | 1.28 | 155 ± 1 |

General conditions: monomer 20 vol % in H2O + 0.1 M NaBr, T = 65 °C; Vtot = 10 mL, [CuIIBr2/TPMA] = 1 mM, [SDS] = 4.6 wt %, [hexadecane] = 10.8 wt % relative to monomer.

The slope of the ln([M]0/[M]) vs time plot.

Z-average particle diameter by DLS before polymerization.

AsAc feeding rate = 3 μmol/h.

AsAc feeding rate = 2 μmol/h.

AsAc feeding rate = 50 nmol/h and [SDS] = 2.3 wt % relative to monomer.

Figure 4.

GPC traces of polymers with different architectures, prepared by ARGET miniemulsion ATRP. Chain extensions of PBMA-MI with (A) tBMA and (B) BA; multiarm star polymers from β-CD-Br14 macroinitiator and (C) BA or (D) BMA; PBA molecular brushes with DP target (E) 25 and (F) 100. Detailed conditions are listed in Table 5.

Synthesis of Polymer Stars

PBA and PBMA stars were prepared by grafting from a β-cyclodextrin core that was functionalized with 14 ATRP initiators (β-CD-Br14).65 The structure of β-CD-Br14 is illustrated in Scheme 3, while its synthesis is described in the Supporting Information. A clean shift of MW was observed in the GPC traces during the “grafting from” polymerizations with both BA and BMA (Figure 4C,D). PBA star polymers were well-defined (Table 5, entry 3), with Mn,app < Mn,th, since the hydrodynamic volume of a star polymer is lower than its linear analogue with the same MW.65 The formation of the PBMA star polymer was less controlled (Table 5, entry 4).

Synthesis of Polymer Brushes

Molecular brushes were successfully prepared in a miniemulsion by grafting BA from a poly(2-(2-bromoisobutyryloxy)ethyl methacrylate) (PBiBM100) macroinitiator, comprising a methacrylate backbone functionalized with ca. 100 α-bromoisobutyrate initiating sites. The structure of PBiBM100 is illustrated in Scheme 3. Successful synthesis of molecular brushes requires minimal termination to avoid coupling between the multifunctional macromolecules. Indeed, direct injection of AsAc at the beginning of the reaction produced too many radicals and resulted in coupled chains, i.e., gelation (Figure S11A). Therefore, the concentration of radicals was lowered by (i) decreasing SDS concentration (cf. Table 3) and (ii) gradually feeding AsAc to the reaction in order to slowly reduce CuII to the activator CuI state (Table 5, entries 5 and 6). Slightly larger particles were obtained according to DLS, as expected from the lower CSDS, but the final miniemulsion was stable and no gelation was observed. Molecular brushes with side-chain length of DP = 24 and 57 were prepared. In both cases, radical termination by coupling was minimal, according to the low intensity of high MW shoulders in the GPC traces (Figure 4E,F). Again, Mn,app was lower than Mn,th due to the very compact nature of molecular brushes.

3. CONCLUSION

The interaction between hydrophilic catalysts and SDS provided ion-pair and interfacial catalysts suitable for controlled ARGET ATRP of BA, BMA, and tBMA in a miniemulsion polymerization. The setup was simple, with the use of commercially available reagents to prepare in situ a Br–CuIITPMA+/DS− ion-pair complex, followed by reduction with ascorbic acid to activate the polymerization.

The final latexes contained very low amount of residual copper, possibly avoiding the need for any further purification. Indeed, the hydrophilic Br–CuIITPMA+ complex migrated to the aqueous phase when crashing the miniemulsion by dilution. Low dispersity PBMA was obtained by lowering Cu loading to 50 ppm, which resulted in 300 ppb Cu in the final latex. Residual copper content was 10 times lower than when using traditional hydrophobic complexes.

High degrees of polymerization were successfully targeted with both BA and BMA. Moreover, chain extension of a PBMA macroinitiator showed excellent retention of chain-end functionality. Monomodal block copolymers PBMA-block-PBA and PBMA-block-PtBMA with Đ < 1.2 were formed in few hours. Well-defined star and brush polymers were also prepared, showing minimal radical termination by coupling.

Compared to traditional superhydrophobic catalysts, miniemulsion ATRP by interfacial and ion-pair catalysis employs commercially available reagents, readily affording polymers with high purity. The hydrophilic ion-pair catalysts can also potentially be used with water-soluble or amphiphilic initiating systems, opening new avenues for controlled polymerizations in dispersed media that are currently being investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The support from the National Science Foundation (CHE 1707490) and the National Institutes of Health (R01DE020843) is acknowledged. F. Lorandi acknowledges Fondazione Aldo Gini. P. Chmielarz acknowledges Kosciuszko Foundation Fellowship. The authors acknowledge Xiaoyu Gao for the kind help in ICP-MS tests and Guojun Xie for the preparation of PBiBM100 macroinitiator and useful discussions.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b01730.

Characterization of aqueous phase catalysts and additional polymerization results (PDF)

References

- 1.Zetterlund PB, Kagawa Y, Okubo M. Controlled/Living Radical Polymerization in Dispersed Systems. Chem Rev. 2008;108:3747–3794. doi: 10.1021/cr800242x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennings J, He G, Howdle SM, Zetterlund PB. Block Copolymer Synthesis by Controlled/Living Radical Polymerisation in Heterogeneous Systems. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:5055–5084. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00253f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham MF. Controlled/Living Radical Polymerization in Aqueous Dispersed Systems. Prog Polym Sci. 2008;33:365–398. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu M, Ramirez LMF, Lozano AR, Quemener D, Babin J, Durand A, Marie E, Six JL, Nouvel C. First Multi-Reactive Dextran-Based Inisurf for Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization in Miniemulsion. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;130:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saade J, Bordes C, Raffin G, Hangouet M, Marote P, Faure K. Response Surface Optimization of Miniemulsion: Application to UV Synthesis of Hexyl Acrylate Nanoparticles. Colloid Polym Sci. 2016;294:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu L, Glebe U, Boker A. Synthesis of Hybrid Silica Nanoparticles Densely Grafted with Thermo and pH Dual-Responsive Brushes via Surface-Initiated ATRP. Macromolecules. 2016;49:9586–9596. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matyjaszewski K. Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP): Current Status and Future Perspectives. Macromolecules. 2012;45:4015–4039. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. Living Radical Polymerization by the RAFT Process - A Third Update. Aust J Chem. 2012;65:985–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicolas J, Guillaneuf Y, Lefay C, Bertin D, Gigmes D, Charleux B. Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization. Prog Polym Sci. 2013;38:63–235. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Airaud C, Heroguez V, Gnanou Y. Bicompartmentalized Polymer Particles by Tandem ROMP and ATRP in Miniemulsion. Macromolecules. 2008;41:3015–3022. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Airaud C, Ibarboure E, Gaillard C, Heroguez V. Nanostructured Polymer Composite Nanoparticles Synthesized in a Single Step via Simultaneous ROMP and ATRP Under Microemulsion Conditions. J Polym Sci, Part A: Polym Chem. 2009;47:4014–4027. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min K, Matyjaszewski K. Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization in Aqueous Dispersed Media. Cent Eur J Chem. 2009;7:657–674. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun JT, Hong CY, Pan CY. Recent Advances in RAFT Dispersion Polymerization for Preparation of Block Copolymer Aggregates. Polym Chem. 2013;4:873–881. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao J, Zhang LF, Jiang XW, Tian C, Zhao XN, Ke Q, Pan XQ, Cheng ZP, Zhu XL. Facile Iron-Mediated Dispersant-Free Suspension Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate via Reverse ATRP in Water. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2013;34:1747–1754. doi: 10.1002/marc.201300513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Chen WJ, Zhang ZB, Zhang LF, Cheng ZP, Zhu XL. A Surfactant-Free Emulsion RAFT Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate in a Continuous Tubular Reactor. Polym Chem. 2015;6:1937–1943. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagawa Y, Zetterlund PB, Minami H, Okubo M. Compartmentalization in Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP) in Dispersed Systems. Macromol Theory Simul. 2006;15:608–613. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zetterlund PB, Okubo M. Compartmentalization in Nitroxide-Mediated Radical Polymerization in Dispersed Systems. Macromolecules. 2006;39:8959–8967. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomson ME, Cunningham MF. Compartmentalization Effects on the Rate of Polymerization and the Degree of Control in ATRP Aqueous Dispersed Phase Polymerization. Macromolecules. 2010;43:2772–2779. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JS, Matyjaszewski K. Controlled Living Radical Polymerization - Atom-Transfer Radical Polymerization in the Presence of Transition-Metal Complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5614–5615. [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Paoli P, Isse AA, Bortolamei N, Gennaro A. New Insights Into the Mechanism of Activation of Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization by Cu(I) Complexes. Chem Commun. 2011;47:3580–3582. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10195a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simakova A, Averick SE, Konkolewicz D, Matyjaszewski K. Aqueous ARGET ATRP. Macromolecules. 2012;45:6371–6379. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Payne KA, D’hooge DR, van Steenberge PHM, Reyniers MF, Cunningham MF, Hutchinson RA, Marin GB. ARGET ATRP of Butyl Methacrylate: Utilizing Kinetic Modeling to Understand Experimental Trends. Macromolecules. 2013;46:3828–3840. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matyjaszewski K, Jakubowski W, Min K, Tang W, Huang JY, Braunecker WA, Tsarevsky NV. Diminishing Catalyst Concentration in Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization with Reducing Agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15309–15314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602675103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matyjaszewski K, Tsarevsky NV, Braunecker WA, Dong H, Huang J, Jakubowski W, Kwak Y, Nicolay R, Tang W, Yoon JA. Role of Cu0 in Controlled/”Living” Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules. 2007;40:7795–7806. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Wang Y, Matyjaszewski K. ATRP of Methyl Acrylate with Metallic Zinc, Magnesium, and Iron as Reducing Agents and Supplemental Activators. Macromolecules. 2011;44:683–685. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konkolewicz D, Wang Y, Krys P, Zhong MJ, Isse AA, Gennaro A, Matyjaszewski K. SARA ATRP or SET-LRP. End of controversy? Polym Chem. 2014;5:4396–4417. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams VA, Matyjaszewski K. Expanding the ATRP Toolbox: Methacrylate Polymerization with an Elemental Silver Reducing Agent. Macromolecules. 2015;48:6457–6464. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams VA, Ribelli TG, Chmielarz P, Park S, Matyjaszewski K. A Silver Bullet: Elemental Silver as an Efficient Reducing Agent for Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization of Acrylates. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1428–1431. doi: 10.1021/ja512519j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bortolamei N, Isse AA, Magenau AJD, Gennaro A, Matyjaszewski K. Controlled Aqueous Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization with Electrochemical Generation of the Active Catalyst. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:11391–11394. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magenau AJD, Strandwitz NC, Gennaro A, Matyjaszewski K. Electrochemically Mediated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Science. 2011;332:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1202357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S, Chmielarz P, Gennaro A, Matyjaszewski K. Simplified Electrochemically Mediated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization using a Sacrificial Anode. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:2388–2392. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorandi F, Fantin M, Isse AA, Gennaro A. Electrochemically Mediated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization of n-Butyl Acrylate on Non-platinum Cathodes. Polym Chem. 2016;7:5357–5365. doi: 10.1002/marc.201600237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chmielarz P, Fantin M, Park S, Isse AA, Gennaro A, Magenau AJD, Sobkowiak A, Matyjaszewski K. Electrochemically Mediated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (eATRP) Prog Polym Sci. 2017;69:47–78. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konkolewicz D, Schroder K, Buback J, Bernhard S, Matyjaszewski K. Visible Light and Sunlight Photoinduced ATRP with ppm of Cu Catalyst. ACS Macro Lett. 2012;1:1219–1223. doi: 10.1021/mz300457e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan XC, Tasdelen MA, Laun J, Junkers T, Yagci Y, Matyjaszewski K. Photomediated Controlled Radical Polymerization. Prog Polym Sci. 2016;62:73–125. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohapatra H, Kleiman M, Esser-Kahn AP. Mechanically Controlled Radical Polymerization Initiated by Ultrasound. Nat Chem. 2016;9:135–139. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang ZH, Pan XC, Yan JJ, Dadashi-Silab S, Xie GJ, Zhang JN, Wang ZH, Xia HS, Matyjaszewski K. Temporal Control in Mechanically Controlled Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization Using Low ppm of Cu Catalyst. ACS Macro Lett. 2017;6:546–549. doi: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.7b00152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tayal A, Kelly RM, Khan SA. Rheology and Molecular Weight Changes During Enzymatic Degradation of a Water-Soluble Polymer. Macromolecules. 1999;32:294–300. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paik HJ, Kickelbick G, Matyjaszewski K. Immobilization of the Copper Catalyst in Atom-Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules. 1999;32:2941–2947. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matyjaszewski K, Pintauer T, Gaynor S. Removal of Copper-Based Catalyst in Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization Using Ion Exchange Resins. Macromolecules. 2000;33:1476–1478. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gromada J, Spanswick J, Matyjaszewski K. Synthesis and ATRP Activity of New TREN-Based Ligands. Macromol Chem Phys. 2004;205:551–566. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jasinski N, Lauer A, Stals PJM, Behrens S, Essig S, Walther A, Goldmann AS, Barner-Kowollik C. Cleaning the Click: A Simple Electrochemical Avenue for Copper Removal from Strongly Coordinating Macromolecules. ACS Macro Lett. 2015;4:298–301. doi: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.5b00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei YP, Zhang Q, Wang WJ, Li BG, Zhu SP. Improvement on Stability of Polymeric Latexes Prepared by Emulsion ATRP Through Copper Removal Using Electrolysis. Polymer. 2016;106:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsarevsky NV, Matyjaszewski K. Green” Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization: From Process Design to Preparation of Well-Defined Environmentally Friendly Polymeric Materials. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2270–2299. doi: 10.1021/cr050947p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fantin M, Chmielarz P, Wang Y, Lorandi F, Isse AA, Gennaro A, Matyjaszewski K. Harnessing the Interaction between Surfactant and Hydrophilic Catalyst To Control eATRP in Miniemulsion. Macromolecules. 2017;50:3726–3732. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b00530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Min K, Gao HF, Matyjaszewski K. Preparation of Homopolymers and Block Copolymers in Miniemulsion by ATRP Using Activators Generated by Electron Transfer (AGET) J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3825–3830. doi: 10.1021/ja0429364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kagawa Y, Minami H, Okubo M, Zhou H. Preparation of Block Copolymer Particles by Two-Step Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization in Aqueous Media and Its Unique Morphology. Polymer. 2005;46:1045–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simms RW, Cunningham ME. High Molecular Weight Poly(Butyl Methacrylate) via ATRP Miniemulsions. Macromol Symp. 2008;261:32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elsen AM, Burdynska J, Park S, Matyjaszewski K. Active Ligand for Low PPM Miniemulsion Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules. 2012;45:7356–7363. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fantin M, Park S, Wang Y, Matyjaszewski K. Electrochemical Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization in Miniemulsion with a Dual Catalytic System. Macromolecules. 2016;49:8838–8847. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Min K, Yu S, Lee HI, Mueller L, Sheiko SS, Matyjaszewski K. High Yield Synthesis of Molecular Brushes via ATRP in Miniemulsion. Macromolecules. 2007;40:6557–6563. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teo VL, Davis BJ, Tsarevsky NV, Zetterlund PB. Successful Miniemulsion ATRP Using an Anionic Surfactant: Minimization of Deactivator Loss by Addition of a Halide Salt. Macromolecules. 2014;47:6230–6237. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fantin M, Isse AA, Gennaro A, Matyjaszewski K. Understanding the Fundamentals of Aqueous ATRP and Defining Conditions for Better Control. Macromolecules. 2015;48:6862–6875. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang W, Matyjaszewski K. Effect of Ligand Structures on Activation Rate Constants in ATRP. Macromolecules. 2007;40:1858–1863. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang W, Kwak Y, Braunecker W, Tsarevsky NV, Coote ML, Matyjaszewski K. Understanding Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization: Effect of Ligand and Initiator Structures on the Equilibrium Constants. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10702–10713. doi: 10.1021/ja802290a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fantin M, Isse AA, Bortolamei N, Matyjaszewski K, Gennaro A. Electrochemical Approaches to the Determination of Rate Constants for the Activation Step in Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Electrochim Acta. 2016;222:393–401. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mastan E, Zhu SP. A Molecular Weight Distribution Polydispersity Equation for the ATRP System: Quantifying the Effect of Radical Termination. Macromolecules. 2015;48:6440–6449. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nanda AK, Matyjaszewski K. Effect of Penultimate Unit on the Activation Process in ATRP. Macromolecules. 2003;36:8222–8224. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jakubowski W, Matyjaszewski K. Activators Regenerated by Electron transfer for Atom-Transfer Radical Polymerization of (Meth)Acrylates and Related Block Copolymers. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:4482–4486. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang W, Matyjaszewski K. Effects of Initiator Structure on Activation Rate Constants in ATRP. Macromolecules. 2007;40:1858–1863. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krys P, Matyjaszewski K. Kinetics of Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Eur Polym J. 2017;89:482–523. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beuermann S, Buback M, Davis TP, Gilbert RG, Hutchinson RA, Kajiwara A, Klumperman B, Russell GT. Critically Evaluated Rate Coefficients for Free-Radical Polymerization, 3. Propagation Rate Coefficients for Alkyl Methacrylates. Macromol Chem Phys. 2000;201:1355–1364. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Egorova KS, Ananikov VP. Which Metals are Green for Catalysis? Comparison of the Toxicities of Ni, Cu, Fe, Pd, Pt, Rh, and Au Salts. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:12150–12162. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fukuda T, Goto A. Gel Permeation Chromatographic Determination of Activation Rate Constants in Nitroxide-controlled Free Radical Polymerization, 2. Analysis of Evolution of Polydispersities. Macromol Rapid Commun. 1997;18:683–688. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chmielarz P, Park S, Sobkowiak A, Matyjaszewski K. Synthesis of Beta-Cyclodextrin-Based Star Polymers via a Simplified Electrochemically Mediated ATRP. Polymer. 2016;88:36–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.