Abstract

The availability of high-throughput genomic assays and rich electronic medical records allows us to identify cancer subtypes with greater accuracy and resolution. The integration of multiplatform, heterogenous, and high dimensional data remains an enormous challenge in using big data in bioinformatics research. Previous methods have been developed for patient stratification, however, these approaches did not incorporate prior knowledge and offer limited biology insight. New computational methods are needed to better utilize multiple types of information to identify clinically meaningful subtypes. Recent studies have shown that many immune functional genes are associated with cancer progression, recurrence and prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Therefore, we developed a novel immune signaling based Cascade Propagation (CasP) subtyping approach to stratify HNSCC patients. Unlike previous stratification methods that use only patient genomic data, our approach makes use of prior biological information such as immune signaling and protein-protein interactions, as well as patient survival information. CasP is a multi-step stratification procedure, composed of a dynamic network tree cutting step followed by a mutational stratification step. Using this approach, HNSCC patients were first stratified into clinically relative subgroups with different survival outcomes and distinct immunogenic features. We found that the good outcome of a subgroup of HNSCC patients was due to an enhanced immune response. The gene sets were characterized by a significant activation of T cell receptor signaling pathways, in addition to other important cancer related pathways such as PI3K and JAK/STAT signaling pathways. Further stratification of patients based on somatic mutation profiles detected three survival-distinct subnetworks. Our newly developed CasP subtyping approach allowed us to integrate multiple data types and identify clinically relevant subtypes of HNSCC patients.

Keywords: Patient stratification, Cascade Propagation subtyping, Immune signaling

1. Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a group of biologically similar cancers which develops from the mucosal lining of the upper aerodigestive tract [1,2]. It is the sixth most common malignancy in the world, with more than 550,000 cases annually worldwide [3,4]. The five-year survival rate of patients with HNSCC is about 60% and has not markedly improved over the past few decades [3,5]. The severe heterogeneity among HNSCC patients makes it difficult to detect useful biomarkers for clinical outcome prediction and treatment [6,7]. To better understand HNSCC development and recurrence, new computational modeling is needed to stratify patients into biologically meaningful subtypes with different clinical outcomes. However, the heterogeneity of data source and high dimensionality characteristics of big data makes it difficult to work with [8]. Various genomics and the second generation sequencing technologies have generated numerous heterogeneous data. All these data are available on TCGA, TARGET, CGCI, and ICGC consortiums [9,10]. The number of samples and sequencing reads stored in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and Sequence Read Archive (SRA) databases increased exponentially in the past few years. As of March 2016, GEO contains 1,768,216 samples and SRA has 1,352,046 samples of sequencing data. Different omics data such as transcriptome data, whole genome sequencing data, SNP array data, DNA methylation data, reverse phase protein array data are generated from different labs and different platforms. How to mine the heterogeneity and achieve dimension reduction are the challenges of big data analysis.

To deal with both the challenges of big data and the challenge of patient stratification, effective integrative methods are urgently required to fully utilize public data. Advancement in big data analysis will allow us to properly stratify patients and guide treatment and disease subtyping, as well as reveal disease mechanism and discover new targets. The standard approach for integrating multiple cancer genomic datasets, such as Constructing Optimal Cluster Architecture or “COCA”, is to perform cluster analysis on each cancer data type individually and then integrate the diverse platform-specific cluster assignments to group tumors into subtypes that shared features across multiple datasets [11]. Unfortunately, this approach is not bi-clustering, which means that it does not cluster samples and signatures to patterns simultaneously [12,13]. Another recent clustering approach, called integrative cluster (iCluster), can capture the associations among different data types and variance-covariance structures within data types in one model. However, despite various studies that have used genomic data to stratify cancer patients, most did not take into account prior knowledge and clinical phenotypes in their patient stratification and some of the identified pathways were not druggable [14–16].

Accumulating evidence indicates the importance of the immune system in controlling the progression of tumors. The immune system has been recognized as an extrinsic tumor-suppressor that can detect and destroy abnormal cells and prevent the development of HNSCC [17–20]. Immune cells and other normal cells make up the HNSCC microenvironment and they can communicate with cancer cells and affect their development and progression [21,22]. The difference in immune responses between patients may explain the mechanism of cancer resistance and progression, and may provide new treatment strategies. Therefore, we developed a novel Cascade Propagation (CasP) subtyping approach to investigate co-dependent immune signaling pathways involved in HNSCC. CasP is a two-stage subtyping approach with a dynamic network tree cutting step followed by a somatic mutational stratification step. Distinct from molecular-based approaches, the dynamic network tree cutting method uses signaling interaction information to explain immune responses within HNSCC patients. Because somatic mutation profiles of cancers can also stratify cancer patients, we employed a non-negative matrix factorization-based clustering to further stratify HNSCC patients based on their somatic mutation profiles [16,23]. Network propagation was applied to smooth the network profile for each patient since mutations were not frequent. IPA was used to identify enriched pathways in the subtypes of HNSCC patients.

The etiology and pathogenesis of HNSCC are also influenced by environmental factors. Although consumption of alcohol and tobacco are known to be primary risk factors for HNSCC [24,25], recent studies of epidemiology have found that infection with human papilloma viruses (HPVs) is also an important risk factor for HNSCC cancer. Oncogenic HPV types, especially HPV-16 and HPV-18, have been found to be the cause of up to 70% HNSCC [26–28]. We further investigated the clinical characteristics of our subtypes. EGFR overexpression has been associated with poor survival of HNSCC patients; however, EGFR inhibition as a monotherapy has not been very successful in the past [29–31]. Given the cytotoxic and non-specific nature of standard cancer therapies and the limited efficacies of EGFR treatments, there is a tremendous need for development of effective targeted therapies with minimal negative effects on the quality of life of individuals. The incorporation of important signaling information in our new CasP stratification approach will offer more insights and generated biologically interpretable results that can explain the mechanisms of HNSCC progression.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient clinical and genomic data

Clinical data were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data portal in June 2014. Surviving time for each patient is determined by the date of death or last time of visit. Only 377 patients had survival information. The HPV status of this cohort was also extracted from TCGA clinical dataset for further survival analysis. Level 3 normalized RNA-Seq data and level 2 somatic mutation data were also obtained from TCGA. Only RNA-Seq data generated using the IlluminaHiSeq_RNAseqV2 platform was used. Based on clinical data, we retained 377 patients with 19,978 genes from the cohort. For somatic mutation data, we only used data created by the Illumina GA platform. Screening the mutation data, we constructed a binary matrix with rows representing genes and columns representing the bit vectors for each patient mutation status. Excluding the patients with fewer than 10 mutations, we obtained 369 patients with 16,610 corresponding mutated genes.

2.2. Immune signaling interaction database

We employed publicly available database InnateDB (http://www.innatedb.com, download in May 2014) for immune protein interactions. InnateDB is a knowledge resource for innate immunity which contains more than 196,000 human, mouse, and bovine experimentally validated molecular interactions. Considering only uniquely-validated interactions for humans, we have identified 11,378 immune-related protein-protein interactions (PPIs) among 1043 proteins.

2.3. Statistical analysis of gene interaction on survival

To associate gene expression level with patient survival status, we fitted a Cox proportional hazards regression model using the R survival package [32]. A likelihood-ratio test and corresponding p-value was calculated to evaluate the association between gene and survival time. To convert gene-level expression values to interaction-level, or ‘network-level’, only protein coding genes that can be mapped to InnateDB were considered. The PPIs in the high-quality immune signaling network were converted to gene-gene interactions. We defined the expression values of gene-gene interaction across patient samples as the combination of the expression levels of a pair of genes and the corresponding P-value in survival analysis. For an interaction genei ↔ genej, its expression value for patient k is defined as:

where p value is the statistical p-value of Cox regression between gene with patient survival time, and Egi and Egj represent the gene expression levels of gene gi and gj in patient k.

2.4. Clustering patients by dynamic network tree cutting

We developed dynamic network tree cutting approach based on Dynamic Tree Cut algorithm [33] to separate immune signaling interactions into functional networks. A Dynamic Tree Cut algorithm cuts a tree structure into branches [33]. Each branch contains a number of gene-gene interactions (corresponding to PPIs after mapping genes to proteins). The roles of gene-gene interactions in both the classification of patients and regression of patients’ survival time were evaluated for every branch. Patients in each branch were clustered into groups based on the expression values of the gene-gene interactions. More specifically, we used the Dynamic Tree Cut algorithm to cut the clustering tree of patients into three groups. If the sample number in a group was lower than a threshold of 30, it would be combined with another group to generate a total of two groups. Otherwise, we would iteratively take one branch as one group and the other two branches as another group. The two groups were then assigned a network status: the patient group with higher average expression values was called Network-positive and the one with lower average expression values was called Network-negative. Next, the performance of each branch in survival analysis was evaluated by Cox proportional-hazards regression model between patients’ network statuses and patients’ survival time.

2.5. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) information

Human PPIs were downloaded from the BioGrid Database in May 2014. BioGrid contains manually curated PPIs from literature. The PPI data set used in this study had 137,506 protein interactions among 13,588 unique proteins.

2.6. Smoothing somatic mutations network

Somatic mutation data are binary, which makes it different from gene expression data. The mutation profiles were mapped to protein interaction networks. Because of the sparse nature of mutations, network propagation was applied to smooth the mutation profile for each patient [34]. The mutated genes were the source nodes in a gene-gene interaction network and the mutation information were propagated to neighboring genes along the edge of the network. The node in each network pumped flow to its neighbors while simultaneously received flow from them. The propagation function is defined as:

where S is a patient-by-gene matrix and W is an adjacent matrix of the gene interaction network. Y is a patient-by-gene matrix representing the initial information. The parameter a is set as 0.5 in iteration which weighs the relative contribution of neighborhoods. This parameter provides the relative importance between the initial information of one gene and the contributing information of other genes. We have tested the value of parameter a within the interval (0.3–0.9) and found that the specific value of parameter a seems to only have a minor effect on the results. Our method can give similar results within a sizable range. The propagation process was run iteratively until the mean square deviation between two consecutive steps was less than 1 × 10−4. The smoothed mutation profiles were normalized by quartile method and used as the input matrix to cluster patients into predefined number of subnetworks.

2.7. Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF)-based clustering

The NMF method was iterated to minimize the objective function:

where F represents the smoothed patient-by-gene matrix that is factorized into two non-negative matrices called subtype prototypes matrix W and mutation prototypes matrix H [23]. The consensus clustering method was employed to get robust results by randomly selecting ninety percent of the patients from the entire dataset for classification. This was repeated 1000 times and the results were put into a co-occurrence matrix. Each number in the matrix indicated the frequency of a pair of patients belonging in the same cluster. Finally, the patients were stratified to different subtypes by using the complete linkage hierarchical clustering approach.

3. Results

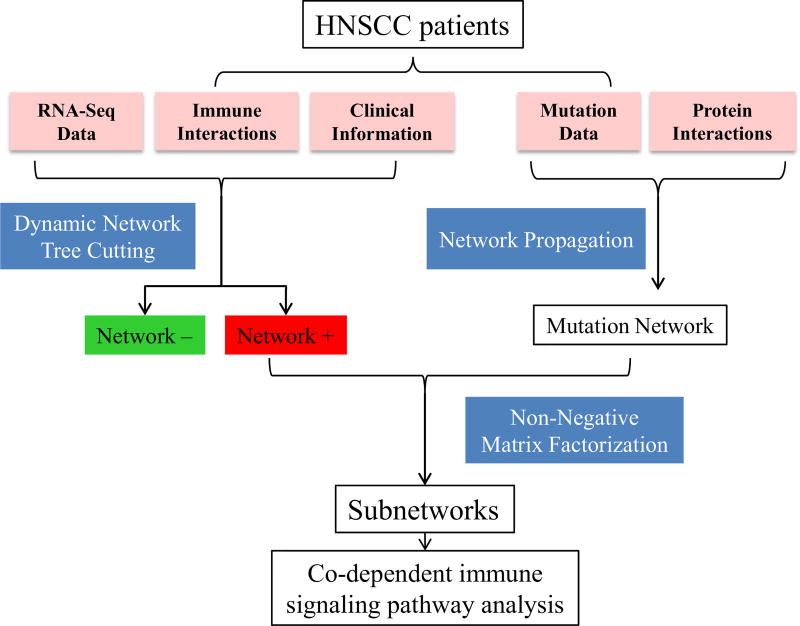

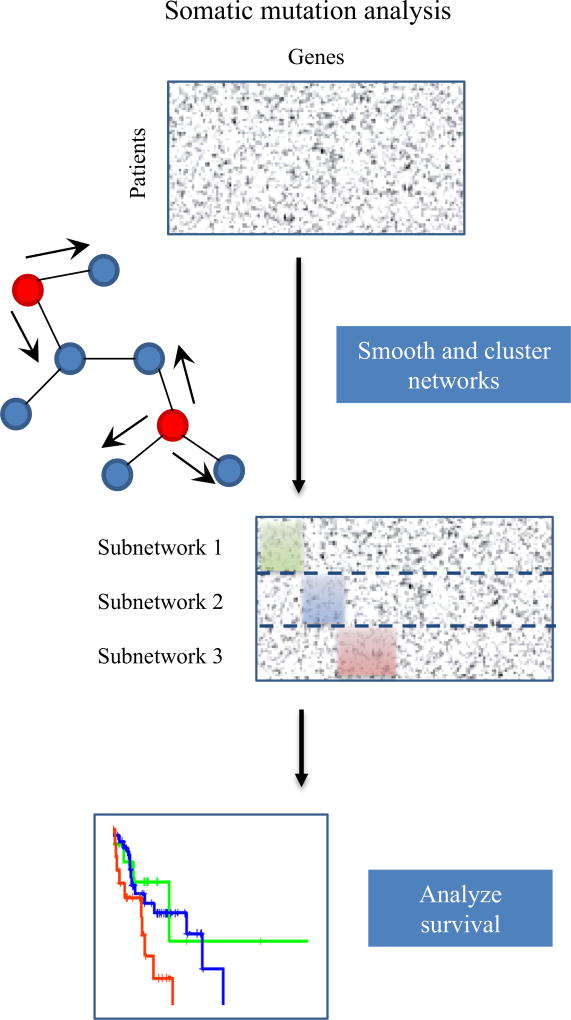

Detection of signaling patterns from gene expression or somatic mutation information was critical to stratify HNSCC patients and identify co-dependent signaling pathways important for HNSCC progression. We developed a novel two-stage subtyping approach called Cascade Propagation (CasP), which is composed of a dynamic network tree cutting followed by mutation propagation and non-negative matrix factorization (NMF)-based clustering, to stratify HNSCC. First, immune protein-protein interactions (PPIs) from InnateDB, and gene expression and clinical information from TCGA are used to cluster patients into two distinct network statuses. Then, mutation data also from TCGA and human PPIs from BioGRID are used to further stratify the networks into subnetworks. Survival analysis showed that these subgroups are associated with different clinical outcomes and functional analysis identified enriched co-dependent immune pathways (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overview of CasP subtyping approach. HNSCC patients are stratified with network-based clustering and further stratified with mutation propagation. Immune signaling information from InnateDB, and gene expression and clinical data from TCGA are used to cluster HNSCC patients into functional networks with two statuses: positive and negative. PPIs from BioGRID and mutational data from TCGA are used to further stratify HNSCC patients. Co-dependent immune signaling pathways are identified in the different subgroups.

3.1. Stratification of HNSCC patients and identification of co-dependent pathways

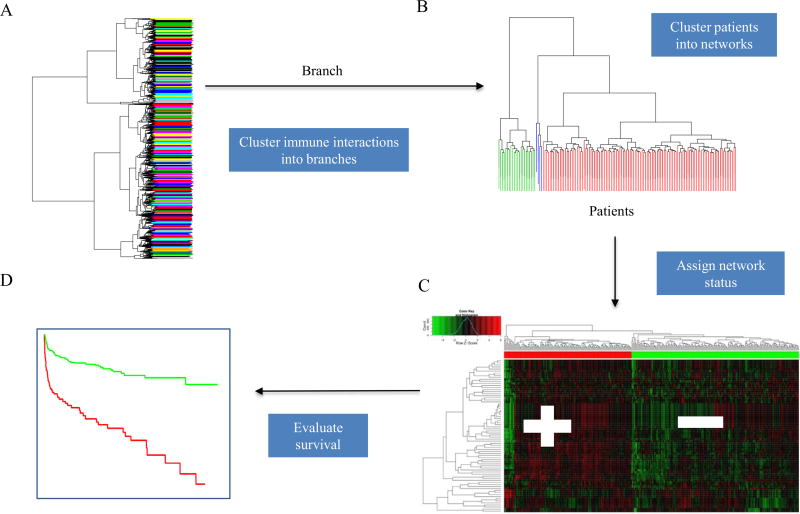

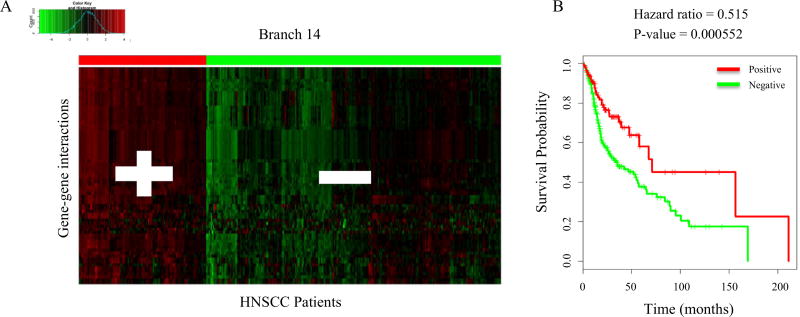

The dynamic network tree cutting method uses signaling interaction information to explain immune responses of HNSCC patients and elucidate candidate anti-tumor pathways. This novel approach is able to cut the clustering tree of immune signaling interactions into functional networks, or branches, using a Dynamic Tree Cut algorithm (Fig. 2A). For each branch, the patients are assigned to two groups with different statuses: Network-positive for higher average expression values and Network-negative for lower average expression values (Fig. 2B and C). Expression values of gene-gene interactions across patient samples were defined as the combination of gene expression levels of each pair of genes and the corresponding p-value in survival analysis. Finally, the performance of each branch in survival was evaluated by Cox proportional-hazards regression model between patients’ network statuses and survival times (Fig. 2D). The branches with Cox regression p-value < 0.05 and the associated coefficients of hazard ratios are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Branches with significantly low p-values will contain signaling interactions that are essential for predicting patients’ survival outcomes. The top ranked branches with the lowest Cox regression p-values are Branch 22, 11, and 14 (Table 1). The hazards ratios of these branches indicate that there is also a survival difference between the Network-positive and Network-negative groups. The two groups of HNSCC patients in Branch 14 and the corresponding survival curve are shown in Fig. 3A and B.

Fig. 2.

The Dynamic Network Tree Cutting Approach. (A) A dynamic tree cut algorithm is used to group immune signaling interactions into functional networks, termed branches. (B) In each branch, the patients are assigned into two groups with different status based on average expression values. (C) The patient status with higher average expression values is marked as Network-positive and the one with lower average expression values is marked as Network-negative. (D) Finally, the performance of each branch is evaluated by Cox proportional-hazards regression model.

Table 1.

Top ranking branches based on Cox regression p-values. Branches are ranked based on Cox regression p-value. The top three branches with the lowest Cox regression P values are listed. The number of genes in the branches and the coefficient of hazard ratios between the Network-positive and Network-negative groups in each branch are shown.

| Branch | Number of genes |

Cox regression P value |

Coefficient of hazard ratios |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 49 | 0.000248 | 0.3987 |

| 11 | 91 | 0.000507 | 0.3715 |

| 14 | 80 | 0.000552 | 0.5155 |

Fig. 3.

Branch 14 network and survival curve. (A) All HNSCC patients in Branch 14 are clustered into two groups based on average expression values. The groups are assigned a network status: Network-positive (Red, +) and Network-negative (Green, −). n = 304 (B) The corresponding survival curve shows the survival difference between the Network-positive and the Network-negative groups in Branch 14. The p-value is <0.05 and the hazard ratio is 0.515.

3.2. Enriched immune signaling pathway

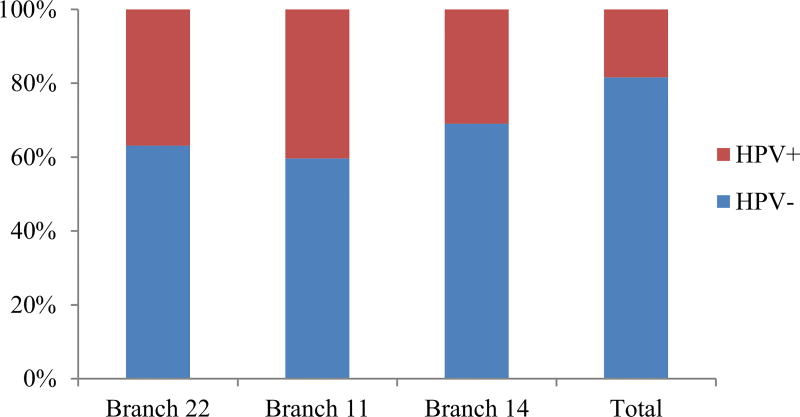

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was used to identify enriched pathways for high ranking branches. The most enriched pathway based on significant p-values was T cell receptor signaling pathway. There were 20 genes involved in T cell receptor signaling pathway in Branch 14, 10 in Branch 22, and 14 in Branch 11. HPV infection is increasingly identified as an important causative factor for HNSCC cancer [26–28]. Patients with HPV+ HNSCC have a significantly better prognosis than HPV− patients [35,36]. The Chi-squared test indicates that HPV+ patients were enriched in Network-positive group in the top three branches (p-value = 5.2E−05, 2.6E−05, and 7.4E−05) (Fig. 4). The Network-positive patients in the top three branches also had a more favorable clinical outcome. Further analysis of Branch 14 shows that more than half of the HPV+ patients were assigned to Network-positive status (Table 2). Functional analysis of the genes in Branch 14 revealed important cancer related pathways, such as P13K signaling pathway (p-value = 3.33E−13) and JAK/STAT signaling pathway (p-value = 3.93E−11), which are already reported in literature to be relevant to cancers [37–41].

Fig. 4.

HPV status in Network-positive group. Percentage of HPV+ patients in the Network-positive groups of the top three branches are shown along with the total percentage of HPV+ patients in the cohort. Red indicates the percentage of HPV+ patients and blue represents the percentage of HPV− patients in the Network-positive groups. P-value = 5.2E–05, 2.6E–05, and 7.4E–05 for Branch 22, 11, and 14, respectively.

Table 2.

Patient HPV status in Network-positive and Network-negative subgroups. Patients’ HPV statuses in the two networks in Branch 14 are shown. The values indicate the number of patients in each category.

| Network positive | Network negative | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPV+ | 35 | 34 | 69 |

| HPV− | 78 | 227 | 305 |

| Total | 113 | 261 | 374 |

3.3. Somatic mutation propagation for further stratification

Some cancers have been successfully stratified based on somatic mutation profiles [16]. Since more than half of the HPV+ patients were assigned to Network-positive status in Branch 14, we focused on this branch for further mutational analysis. In Branch 14, 168 patients had mutations in the PI3K signaling pathway, and 56 patients and 69 patients had mutations in the JAK/STAT signaling pathway and T cell receptor signaling pathway, respectively. Mutational status can provide more information to stratify HNSCC patients into different subtypes. Thus, we conducted somatic mutation analysis to further stratify HNSCC patients using a non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) approach. Briefly, this stratification process consisted of three steps which are highlighted in Fig. 5. First, a somatic mutation network was generated by mapping mutated genes to a protein interaction network. Approximately 295 patients (80%) had ≤200 gene mutations. Because mutations are not frequent, network propagation was applied to smooth the mutation profile for each patient. Then, using the NMF algorithm, patients were clustered into subtypes according to the similarity of their smoothed mutation profile. Lastly, the association between the subtypes and clinical data was evaluated using Cox proportional-hazards regression models.

Fig. 5.

Overview of somatic mutation analysis. A smoothed somatic mutation network is generated using network propagation and HNSCC patients are further stratified into three subnetworks using NMF-based approach. The survival outcomes of the three subnetworks are evaluated with Cox proportional-hazards regression model.

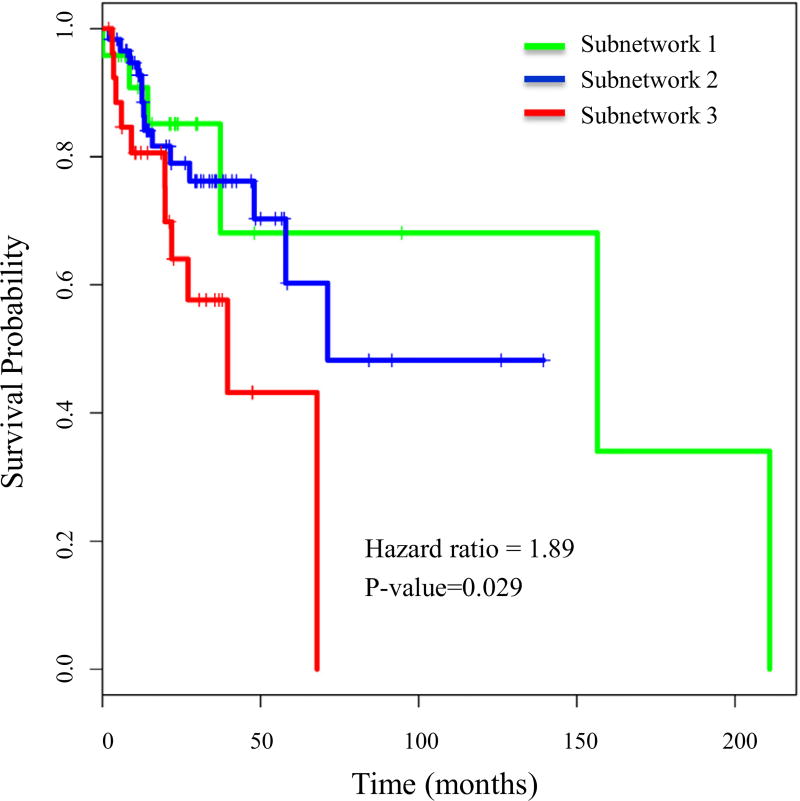

Network propagation was applied to Network-positive and Network-negative groups to further stratify them into 2–5 subnetworks. The p-value from Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to determine biologically meaningful subtypes. Branch 14′s Network-positive group was further stratified into three distinguished subnetworks with different survival distribution (p value = 0.029), whereas the Network-negative group did not further stratify into subnetworks with different survival outcomes (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Cox survival analysis of subnetworks. The Network-positive group of Branch 14 was further stratified into three subnetworks using mutation information. The survival curve, p-value, and hazard ratio are shown.

3.4. Distinct clinical characteristics for subnetworks

The three subnetworks have distinct somatic mutations and different survival distribution. Subnetwork 1 and Subnetwork 3 had a similar number of patients (20 and 21, respectively), however, patients in Subnetwork 1 had a better survival outcome and those in Subnetwork 3 had a poor outcome. Clinical analysis of these patients showed that there were more patients in stage 1 and stage 2 in Subnetwork 1 than in Subnetwork 3. This suggests that somatic mutation information can stratify HNSCC patients and the mutation profiles can distinguish between early and late stage patients and may also define prognosis. HPV+ status were equally distributed in the three subtypes. Smoking was still a high risk factor associated with patient survival, and there were only six smokers in the good outcome Subnetwork 1 compared to 14 smokers in poor outcome Subnetwork 3. The effect of alcohol was not significant. More patients in Subnetwork 3 were undergoing radiation or drug therapy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of Subnetworks. Clinical data of patients in Subnetwork 1 and 3 are presented. Patient tumor stage, HPV status, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, and tumor treatment information are listed.

| Subnetwork 1 | Subnetwork 3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I | 1 | 0 |

| Stage II | 8 | 5 |

| Stage III | 2 | 4 |

| Stage IVA | 11 | 16 |

| Stage IVB | 1 | 2 |

| HPV+ | 7 | 8 |

| HPV− | 16 | 19 |

| Smoker | 6 | 14 |

| Reformed smoker | 11 | 8 |

| Non-smoker | 7 | 5 |

| Alcohol | 17 | 20 |

| No alcohol | 7 | 7 |

| Chemotherapy | 6 | 9 |

| Radiotherapy | 11 | 16 |

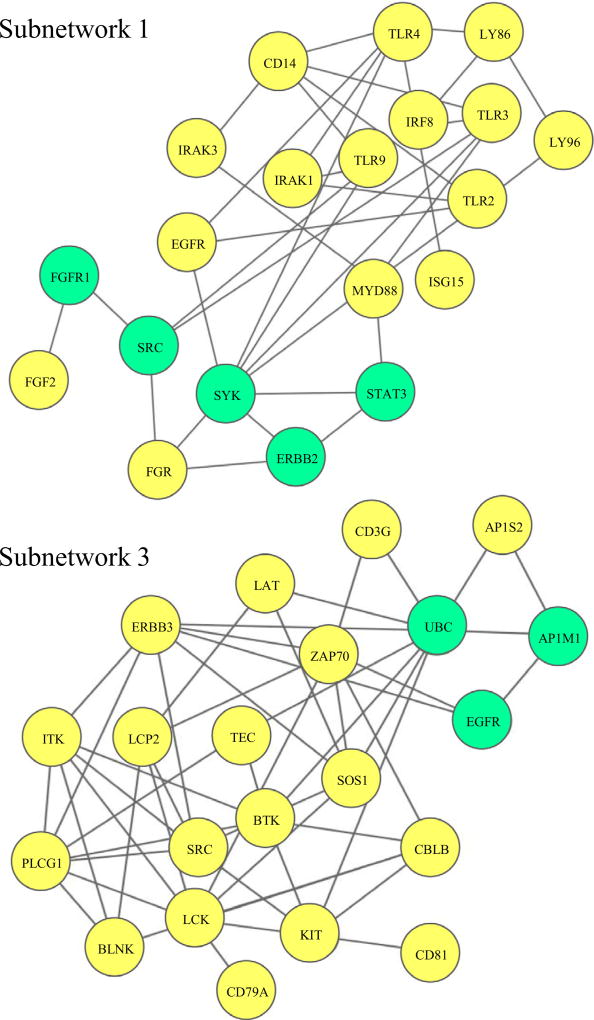

3.5. Network analysis of mutation subnetworks

The subnetworks generated after somatic mutation propagation and NMF clustering further stratified HNSCC patients into distinct groups. Using student’s t-test, three sets of significantly mutated genes were identified (Table 4). To construct a fully connected subnetwork, other related signaling pathways were investigated. Five connecting genes for Subnetwork 1, two for Subnetwork 2, and three for Subnetwork 3 were used to link the genes in a connected network (Fig. 7). Biological functional analysis of Subnetwork 1 showed that approximately 50% of identified genes belonged to Toll-like receptor (TLR)-associated signaling pathways, including CD14, IRAK1, IRAK3, IRF8, LY86, LY96, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR9, and MYD88 [42,43]. TLR is an important family of evolutionally conserved pattern recognition receptor that plays an essential role in innate immune response and the regulation of adaptive immunity [44]. Currently there are at least 11 functional TLRs identified in humans, and activation of TLRs often indicates secretion of inflammatory cytokines, activation of adaptive immunity, and maturation of dendritic cells [45–47]. The patients in Subnetwork 3 had poor survival and the genes were associated with adaptive immune pathways, such as BLNK, BTK, CBLB, CD3, CD79A, CD81, ITK, Kit, LAT, LCK, LCP2 (SLP-76), PLCγ1, SOS1, SRC, and Zap70. Many of these genes are involved in T cell receptor (TCR) signaling [48–50]. CD81 is a transmembrane protein that is highly expressed in all stages of T cell development [51]. Members of the Src family of protein tyrosine kinases, such as SRC and LCK, are responsible for T-cell activation and development [52]. Some genes are related to B cell receptor (BCR) signaling, such as BLNK, BTK, CD79A, and PLCγ1 [53,54].

Table 4.

Identified genes in each subnetwork. Patients were further stratified into three subnetworks using mutational data. Significantly mutated genes and connecting genes are listed. Connecting genes are genes that link the other genes in a coherent network.

| Genes | Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Subnetwork 1 | CD14; EGFR; ERBB2; FGR; FGF2; FGFR1; IRAK1; IRAK3; IRF8; ISG15; LY86; LY96; MYD88; SRC; STAT3; SYK; TLR2; TLR3; TLR4; TLR9; | 20 |

| Subnetwork 2 | BTK; CBLB; DHX58; ERBB3; IRF8; LY86; LY96; NCF2; SOS1; TLR4; TRAF6; UBC; | 12 |

| Subnetwork 3 | AP1M1; AP1S2; BLNK; BTK; CBLB; CD3G; CD79A; CD81; EGFR; ERBB3; ITK; KIT; LAT; LCK; LCP2; PLCG1; SOS1; SRC; TEC; UBC; ZAP70 | 21 |

Fig. 7.

Fully connected subnetworks after further stratification with mutational data. The nodes in yellow are mutated genes in each subnetwork. The nodes in green are linking genes. The complete network for Subnetwork 1 and 3 are shown.

4. Discussion

The major issues in current therapies for HNSCC are disease recurrence and resistance to therapy, and current treatment regimens including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy often lead to excess morbidity and reduced patient’s quality of life. The recent advances in genomics, bioinformatics, and systems biology methods give us the opportunities to identify molecular alterations and allow us to explore the abnormalities of cancers based on large data sets from TCGA. The challenge of integrating heterogenous and high dimensional data has limited the potential of big data. Consequently, we have developed a unique and novel patient stratification method. Our approach is an immune CasP subtyping procedure, which is composed of a dynamic network tree cutting approach followed by a NMF mutation-based stratification. Unlike previous stratification methods, CasP utilizes not only genomic data, but also prior signaling and interaction information. Thus, our approach offers more insights and biologically interpretable results. HNSCC patients were stratified into clinically meaningful subtypes using multiple data types and co-dependent signaling pathways were identified. Network analysis showed that gene sets are characterized by a significant activation of T cell receptor signaling pathways, as well as other important cancer related pathways such as PI3K and JAK/STAT. Differences in gene expressions were able to separate HNSCC patients into two distinct groups. Identification of immune signaling networks that play a role in HNSCC patient survival would not be possible without the development of novel subtyping approaches.

Patient stratification using mutation data has been a challenge in the past due to the sparse nature of mutations. However mutational information can provide more information to stratify patients into different subtypes. To bypass this challenge, mutation profiles were mapped to protein interaction networks and network propagation was applied to smooth the mutation profile. Further stratification with mutation data identified three subnetworks with distinct molecular profiles and different survival outcomes. The patients in Subnetwork 1 had mutations in genes associated with TLR signaling pathways whereas those in Subnetwork 3 had mutations in genes associated with T cell receptor and B cell receptor signaling. Since TLRs primarily recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns, they play a critical role in innate immune responses, which is not extremely important for tumor cell recognition and targeting. Therefore these patients have a relatively better survival. On the other hand, patients in Subnetwork 3 have poorer survival. These patients have mutation in the T cell and B cell receptor signaling pathways, which may affect T cell or B cell activation. This suggests a functional adaptive immune system may be important for better survival outcomes for HNSCC patients. Many co-stimulatory receptors, such as CD28 and CD45, were also mutated and these regulate TCR activation. Elevated expression of EGFR was seen in over 67% HNSCC patients and it was correlated with poor prognosis. Because of EGFR’s critical role in survival and proliferation, it has been a commonly used target of anticancer treatment. Our novel CasP subtyping approach allows us to stratify HNSCC patients into subgroups using multiple types of data. Our method can facilitate the identification of co-dependent immune signaling pathways important for HNSCC progression and guide the discovery of relevant druggable targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH 1U01CA166886-01, NIH 1U54TR001420-01, and P30 CA012197. This work was also partially supported by NSFC No. 61373105. We would also like to acknowledge other members of our lab for their valuable discussions and advice.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.06.018.

References

- 1.Pignon J, Bourhis J, Domenge CO, Designe L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. Lancet. 2000;355:949–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vokes EE, Weichselbaum RR, Lippman SM, Hong WK. Head and neck cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;328:184–194. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301213280306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Rosenberg PS, Bray F, Gillison ML. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:4550–4559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mroz EA, Rocco JW. MATH, a novel measure of intratumor genetic heterogeneity, is high in poor-outcome classes of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Argiris A, Karamouzis MV, Raben D, Ferris RL. Head and neck cancer. Lancet. 2008;371:1695–1709. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60728-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan J, Han F, Liu H. Challenges of big data analysis. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2014;1:293–314. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwt032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson TJ, Anderson W, Aretz A, et al. International network of cancer genome projects. Nature. 2010;464(7291):993–998. doi: 10.1038/nature08987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Cao J, Xiong J. Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS), 15th International Conference on. IEEE; 2009. Constructing optimal clustering architecture for maximizing lifetime in large scale wireless sensor networks; pp. 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- 12.C.G.A.R. Network. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoadley KA, Yau C, Wolf DM, Cherniack AD, Tamborero D, Ng S, Leiserson MD, Niu B, McLellan MD, Uzunangelov V. Multiplatform analysis of 12 cancer types reveals molecular classification within and across tissues of origin. Cell. 2014;158:929–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.C.G.A.R. Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konstantinopoulos PA, Spentzos D, Cannistra SA. Gene-expression profiling in epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2008;5:577–587. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofree M, Shen JP, Carter H, Gross A, Ideker T. Network-based stratification of tumor mutations. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1108–1115. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wanebo HJ, Jun MY, Strong EW, Oettgen H. T-cell deficiency in patients with squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Am. J. Surg. 1975;130:445–451. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(75)90482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyford-Pike S, Peng S, Young GD, Taube JM, Westra WH, Akpeng B, Bruno TC, Richmon JD, Wang H, Bishop JA. Evidence for a role of the PD-1: PD-L1 pathway in immune resistance of HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1733–1741. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:24–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L, Pang Y, Moses HL. TGF-β and immune cells: an important regulatory axis in the tumor microenvironment and progression. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee DD, Seung HS. Learning the parts of objects by non-negative matrix factorization. Nature. 1999;401:788–791. doi: 10.1038/44565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sturgis EM, Wei Q, Spitz MR. Seminars in oncology. Elsevier; 2004. Descriptive Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Head and Neck Cancer; pp. 726–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talamini R, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C, Dal Maso L, Levi F, Bidoli E, Negri E, Pasche C, Vaccarella S, Barzan L. Combined effect of tobacco and alcohol on laryngeal cancer risk: a case–control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:957–964. doi: 10.1023/a:1021944123914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione M, Symer DE. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–720. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Begum S, Cao D, Gillison M, Zahurak M, Westra WH. Tissue distribution of human papillomavirus 16 DNA integration in patients with tonsillar carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:5694–5699. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:467–475. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vermorken JB, Trigo J, Hitt R, Koralewski P, Diaz-Rubio E, Rolland F, Knecht R, Amellal N, Schueler A, Baselga J. Open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of cetuximab as a single agent in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck who failed to respond to platinum-based therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:2171–2177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen EE, Kane MA, List MA, Brockstein BE, Mehrotra B, Huo D, Mauer AM, Pierce C, Dekker A, Vokes EE. Phase II trial of gefitinib 250 mg daily in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:8418–8424. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soulieres D, Senzer NN, Vokes EE, Hidalgo M, Agarwala SS, Siu LL. Multicenter phase II study of erlotinib, an oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:77–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fox J. Cox proportional-hazards regression for survival data. An R and S-PLUS Companion to Applied Regression. 2002:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langfelder P, Zhang B, Horvath S. Defining clusters from a hierarchical cluster tree: the Dynamic Tree Cut package for R. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:719–720. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanunu O, Magger O, Ruppin E, Shlomi T, Sharan R. Associating genes and protein complexes with disease via network propagation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dayyani F, Etzel CJ, Liu M, Ho C-H, Lippman SM, Tsao AS. Meta-analysis of the impact of human papillomavirus (HPV) on cancer risk and overall survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Syrjänen S. The role of human papillomavirus infection in head and neck cancers. Ann. Oncol. 2010;21:vii243–vii245. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong K-K, Engelman JA, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K signaling pathway in cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2010;20:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lui VW, Hedberg ML, Li H, Vangara BS, Pendleton K, Zeng Y, Lu Y, Zhang Q, Du Y, Gilbert BR. Frequent mutation of the PI3K pathway in head and neck cancer defines predictive biomarkers. Cancer Discovery. 2013;3:761–769. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagpal JK, Mishra R, Das BR. Activation of Stat-3 as one of the early events in tobacco chewing-mediated oral carcinogenesis. Cancer. 2002;94:2393–2400. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai SY, Johnson FM. Defining the role of the JAK-STAT pathway in head and neck and thoracic malignancies: implications for future therapeutic approaches. Drug Resistance Updates. 2010;13:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshikawa H, Matsubara K, Qian G-S, Jackson P, Groopman JD, Manning JE, Harris CC, Herman JG. SOCS-1, a negative regulator of the JAK/STAT pathway, is silenced by methylation in human hepatocellular carcinoma and shows growth-suppression activity. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:29–35. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1-and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hemmi H, Akira S. TLR Signalling and the Function of Dendritic Cells. 2005 doi: 10.1159/000086657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arpaia E, Shahar M, Dadi H, Cohen A, Rolfman CM. Defective T cell receptor signaling and CD8+ thymic selection in humans lacking zap-70 kinase. Cell. 1994;76:947–958. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cooke MP, Abraham KM, Forbush KA, Perimutter RM. Regulation of T cell receptor signaling by a src family protein-tyrosine kinase (p59 fyn) Cell. 1991;65:281–291. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90162-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang W, Sloan-Lancaster J, Kitchen J, Trible RP, Samelson LE. LAT: the ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase substrate that links T cell receptor to cellular activation. Cell. 1998;92:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80901-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boismenu R, Rhein M, Fischer WH, Havran WL. A role for CD81 in early T cell development. Science. 1996;271:198. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palacios EH, Weiss A. Function of the Src-family kinases, Lck and Fyn, in T-cell development and activation. Oncogene. 2004;23:7990–8000. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Neill SK, Getahun A, Gauld SB, Merrell KT, Tamir I, Smith MJ, Dal Porto JM, Li Q-Z, Cambier JC. Monophosphorylation of CD79a and CD79b ITAM motifs initiates a SHIP-1 phosphatase-mediated inhibitory signaling cascade required for B cell anergy. Immunity. 2011;35:746–756. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dal Porto JM, Gauld SB, Merrell KT, Mills D, Pugh-Bernard AE, Cambier J. B cell antigen receptor signaling 101. Mol. Immunol. 2004;41:599–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.