Abstract

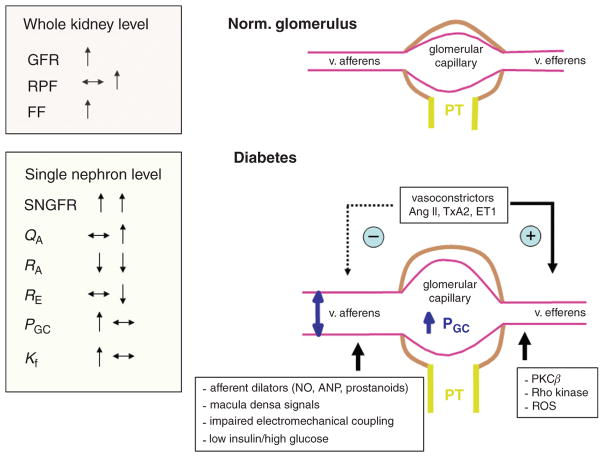

Diabetes mellitus contributes greatly to morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs. In major part, these outcomes derive from the high incidence of progressive kidney dysfunction in patients with diabetes making diabetic nephropathy a leading cause of end-stage renal disease. A better understanding of the molecular mechanism involved and of the early dysfunctions observed in the diabetic kidney may permit the development of new strategies to prevent diabetic nephropathy. Here we review the pathophysiological changes that occur in the kidney in response to hyperglycemia, including the cellular responses to high glucose and the responses in vascular, glomerular, podocyte, and tubular function. The molecular basis, characteristics, and consequences of the unique growth phenotypes observed in the diabetic kidney, including glomerular structures and tubular segments, are outlined. We delineate mechanisms of early diabetic glomerular hyperfiltration including primary vascular events as well as the primary role of tubular growth, hyperreabsorption, and tubuloglomerular communication as part of a “tubulocentric” concept of early diabetic kidney function. The latter also explains the “salt paradox” of the diabetic kidney, that is, a unique and inverse relationship between glomerular filtration rate and dietary salt intake. The mechanisms and consequences of the intrarenal activation of the renin-angiotensin system and of diabetes-induced tubular glycogen accumulation are discussed. Moreover, we aim to link the changes that occur early in the diabetic kidney including the growth phenotype, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and formation of advanced glycation end products to mechanisms involved in progressive kidney disease.

Introduction

Diabetes is the major cause of end-stage renal disease in the United States and elsewhere, and its incidence has increased by about 50% in the past 10 years (644). Notably, only about 20% of individuals with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes (T1DM; T2DM) actually develop nephropathy, indicating that specific genetic and/or environmental factors contribute to its initiation and progression. In fact, family-based studies including genome-wide scans suggest that a significant genetic component confers risk for diabetic nephropathy (73, 265, 266, 336, 553, 567). Moreover, diabetes-induced end-stage renal disease appears to be more likely to be present in African Americans (adjusted odds ratio 1.9), Hispanics (1.4), Asians (1.8), and Native Americans (1.9) than Caucasians (733). The pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy is still incompletely understood and we do not know which genes are critically involved and also can not predict which individual diabetic patient will eventually develop end-stage renal disease. It is urgent to better understand the genes and events that lead from the onset of diabetes to impairment of renal function with the goal of identifying the patients at risk and achieving effective prevention. To prevent diabetic nephropathy, it may prove more reasonable and effective to identify and understand more completely the very early molecular events that initiate the progressive disease.

High-glucose concentrations induce specific cellular effects, which in the kidney affect many types of cells including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, mesangial cells, podocytes, cells of the tubular and collecting duct system and inflammatory cells and myofibroblasts. A better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying these effects is expected to be crucial to better understand the disease. In this regard, it will be important to identify effects that are not only observed in vitro in cultured cells but that are observed in the intact organism and are functionally relevant.

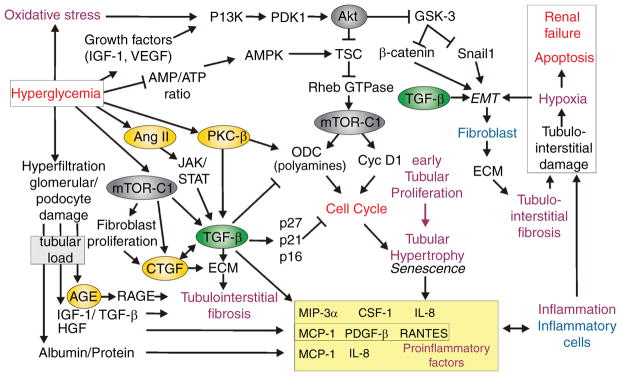

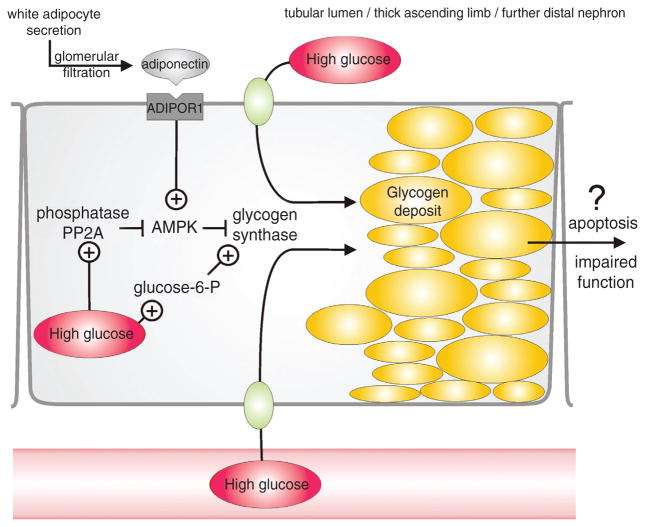

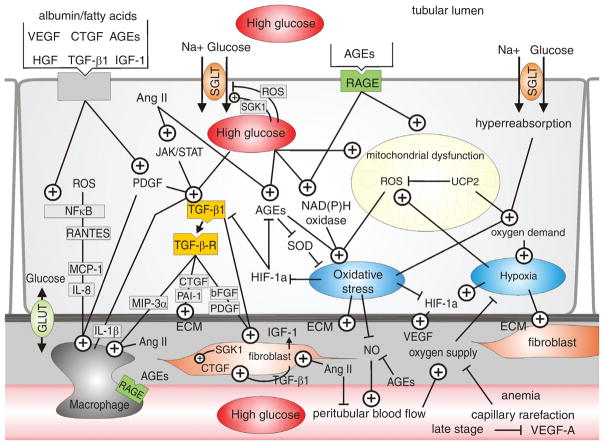

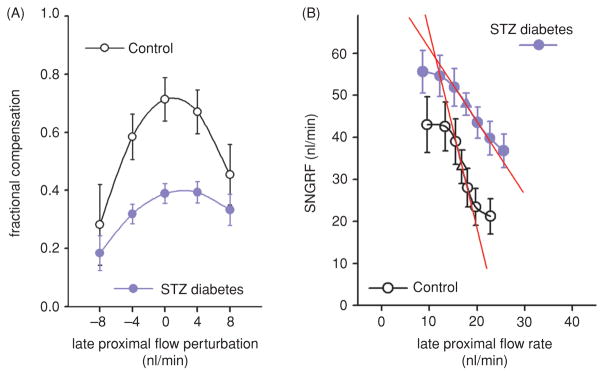

The hemodynamic phenotype in early diabetes is characterized by glomerular hyperfiltration which has been associated with progressive diabetic nephropathy (415), although this is still a matter of debate (see below for further discussion). Glomerular hyperfiltration has been attributed to abnormalities of the glomerulus and preglomerular vessels (447), which are related to changes in the metabolic milieu, vasoactive factors, alterations in signal transduction, as well as intrinsic defects in glomerular arterioles including electromechanical coupling. Albuminuria and proteinuria indicate relevant tissue damage in the diabetic kidney and, besides changes in renal hemodynamics, have been linked to specific alterations in podocyte function. Another notable phenotype of the early diabetic kidney is that it grows. This “growth” phenotype is characterized by enlargement of the kidney through both hyperplasia and hypertrophy which begin at the very onset of diabetes (512). The proximal tubule accounts for most of the cortical mass to begin with, and the proximal tubule also accounts for the greatest share of growth in diabetes (147, 571). As the tubule grows, more of the glomerular filtrate is reabsorbed and less reaches the macula densa (MD) at the end of Henle’s loop. This causes the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) to increase through the normal physiologic action of the tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) system (648). As a consequence of hyperfiltration and the diabetic milieu, the glomeruli filter increased amounts of proteins, growth factors, and advanced glycation end products (AGEs). The diabetic milieu and the prolonged interaction of these proteins and factors with the tubular system trigger renal oxidative stress and cortical interstitial inflammation (2, 3), with the resulting hypoxia and tubulointerstitial fibrosis determining to a great extent the progression of renal disease (33, 65, 126, 154, 198, 386, 396, 581, 606). Moreover, the unique molecular mechanisms involved in the early growth phenotype of the diabetic kidney may contribute to set the stage for long-term kidney failure.

This review addresses these aspects in detail and aims to link changes that occur early in the diabetic kidney to progressive kidney disease. Most of the evidence currently available on these issues has been derived from patients and experimental models with T1DM. Fewer data have been acquired on the early renal pathophysiology in T2DM. While for many aspects similar principles may apply, differences in circulating insulin levels (and C-peptide) and comorbidities are expected to modify the phenotypes in T1DM versus T2DM.

General Mechanisms of Glucose-Induced Cell Injury

The diabetic milieu affects most renal cell types and compartments, although the effects and consequences of high glucose and other components of the diabetic milieu may be specific in individual renal cells. Some cells may be more susceptible to high glucose-induced injury than others. As suggested by Brownlee (86), the cell susceptibility to glucose-induced toxicity is determined by its expression of glucose transporters that mediate cellular uptake of glucose from the extracellular compartment, allowing deleterious increases in intracellular glucose concentrations. Thus, the cell populations most susceptible to the changing milieu of diabetes are those that are unable to sufficiently downregulate glucose uptake and prevent high intracellular glucose levels in the setting of hyperglycemia. In this regard, both mesangial cells (228) and proximal tubular cells (418) are unable to decrease glucose transport rates adequately to prevent excessive changes in intracellular glucose when exposed to high glucose concentrations.

The following sections describe general mechanisms of glucose-induced cell injury that have been implicated in functional and structural changes observed in the diabetic kidney. These mechanisms often act upstream from a variety of processes discussed in the later sections dedicated to specific renal cells, compartments, and functions.

Generation and effects of advanced glycation end products

Prolonged hyperglycemia, but also dyslipidemia and oxidative stress in diabetes result in the production and accumulation of AGEs in the kidney, and at other sites of diabetic complications (86, 92, 591, 612). AGEs are formed by nonenzymatic Maillard or “browning” reaction between carbonyl groups of reducing sugars, like glucose, and amino groups on proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids at a rate determined by a number of factors including intracellular glucose concentrations, pH, and time. The first stable adduct between glucose and protein is fructose-lysine or the Amadori product (see Fig. 1). In addition, the glycation of intracellular proteins is initiated by the elevation of intracellular glucose degradation products (such as glyoxal resulting from glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle), which occurs more rapidly than with glucose itself. These AGEs can be generated from intra-cellular auto-oxidation of glucose to glyoxal, decomposition of early glycation (Amadori) products to 3-deoxyglucosone, and fragmentation of metabolites of the pentose phosphate pathway such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate to the reactive carbonyl methylglyoxal (13). Subsequent rearrangement and fragmentation reactions lead to the formation of AGEs. Under physiological conditions, these reactions are slow. However, in diabetes, persistent hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and oxidative stress all act to hasten the formation of AGEs (86, 87) and modification of both long-lived as well as short-lived proteins (86).

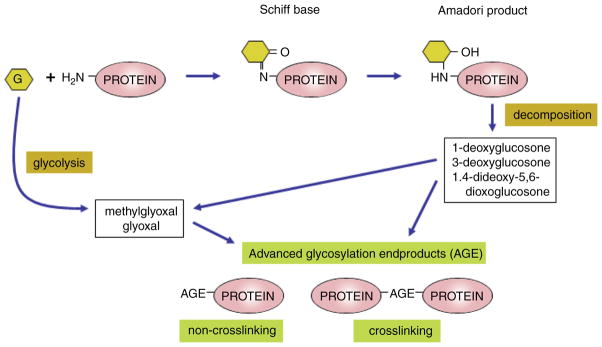

Figure 1.

Simplified biochemistry of advanced glycation end-product formation. Prolonged hyperglycemia, but also dyslipidemia and oxidative stress in diabetes result in the production and accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in the kidney, and at other sites of diabetic complications. AGEs are formed by nonenzymatic Maillard or “browning” reaction between carbonyl groups of reducing sugars, like glucose, and amino groups on proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids. The first stable adduct between glucose and protein is the Amadori product. In addition, the glycation of intracellular proteins is initiated by the elevation of intracellular glucose degradation products or decomposition of early glycation products leading to formation of intermediates such as glyoxal or methylglyoxal. Subsequent rearrangement and fragmentation reactions lead to the formation of AGEs. Under physiological conditions these reactions are slow. However, in diabetes, persistent hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and oxidative stress all act to hasten the formation of AGEs.

AGEs are a chemically heterogeneous group of compounds. The biochemistry of AGEs is remarkably complex and beyond the scope of this article [see (13, 614) for further details]. In brief, Ne-(carboxymethyl)lysine is the simplest and best characterized AGE, derived predominantly from the carbonyl modification of lysine. Tissue Ne-(carboxymethyl)lysine concentrations are increased in diabetes, and elevated levels are associated with the presence of vascular complications in patients with diabetes (47). Other more complex AGEs form “cross-links” both between and within modified proteins, such as pentosidine, MOLD (methylglyoxal lysine dimer) and GOLD (glyoxal lysine dimer). Once AGEs are formed, they are nearly irreversible, although enzymes, such as glyoxalase-1, have the ability to detoxify AGE precursors and inhibit AGE production (579). AGEs induce cell injury and contribute to diabetic complications by changing protein structure and function, such as the formation of cross-links between key molecules of basement membranes and the extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (see Fig. 2). Importantly, AGEs also interact with a receptor (RAGE) on the cell surface thereby altering cellular function (see below).

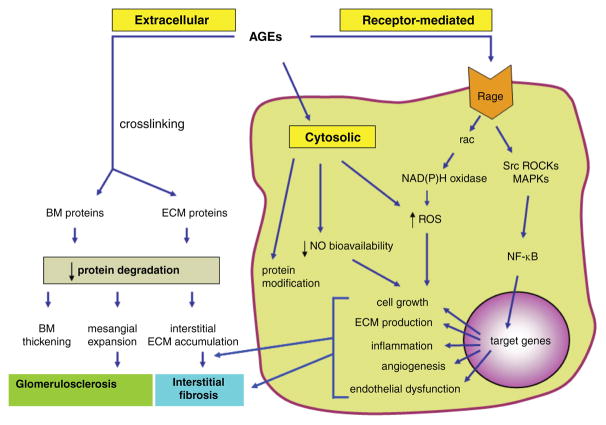

Figure 2.

Consequences of accelerated formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in the diabetic kidney. The schematic shows major mechanisms whereby AGEs exert their harmful effects in the diabetic kidney. AGEs typically crosslink and alter protein structure and function in extracellular compartment, modify cytosolic molecules and exert receptor-mediated effects that lead to activation of multiple signaling pathways and genes implicated in a variety of pathophysiological mechanisms in the diabetic kidney. RAGE, receptor for AGEs; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MAPKs, mitogen-activated protein kinases; ROCKs, Rho kinases; NO, nitric oxide; BM, basement membrane; ECM, extracellular matrix; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B.

Formation of AGEs in the ECM occurs on proteins with a slow turnover rate. Accumulation of AGEs on large matrix proteins such as collagens, fibronectin, and laminin through AGE-AGE intermolecular covalent bonds or cross linking increases collagen stiffness, reduces thermal stability, and causes resistance to digestion by metalloproteinases (MMPs) [reviewed in (614)]. In the kidney, this phenomenon is manifested by expansion of mesangial ECM (580), one of the hallmarks of diabetic nephropathy. In the vascular system, the process results in increased stiffness of the vasculature (300). The physiological relevance of these mechanisms has been validated in experimental studies showing nephroprotective effects of inhibitors of AGE formation (155, 306, 592) or by applying “cross-link breakers,” compounds that dissolve the above-mentioned cross-links between the ECM molecules in experimental diabetic nephropathy (178).

Glycation of extracellular lipids, as evidenced by the increased lipid-linked AGEs in low-density lipoproteins (LDL) samples from persons with diabetes, may also play a role in pathophysiology. For example, glycated LDL can contribute to endothelial dysfunction by reducing nitric oxide (NO) production and suppressing uptake and clearance of LDL through its receptor on endothelial cells (502).

Receptor-mediated effects of advanced glycation end products and their consequences

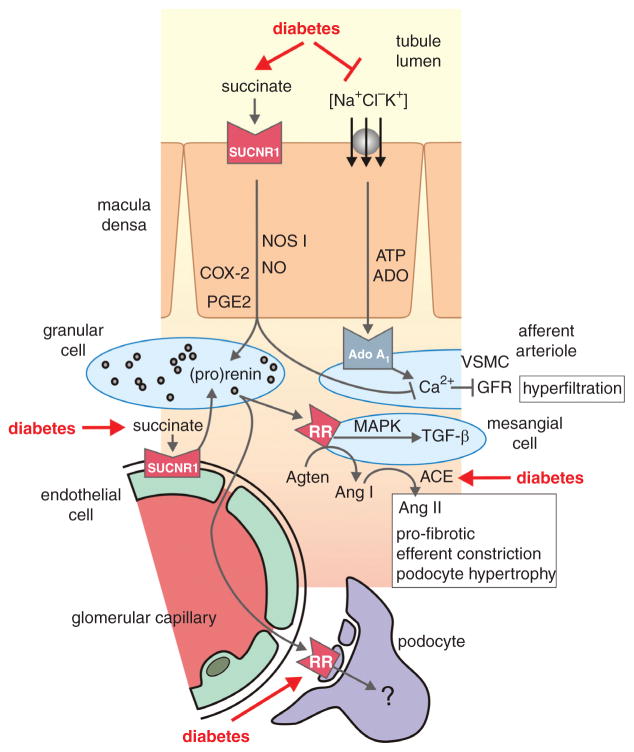

Several different receptors for AGEs have been discovered. The best studied AGE receptor, termed RAGE, initiates the intracellular signaling mechanisms that impair cellular function following the binding of AGEs (see Fig. 2). RAGE is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of receptors involved in inflammatory response (556). Upregulation of RAGE in diabetes occurs in the kidney, vasculature, and mononuclear phagocytes (557, 591). RAGE ligands include AGEs of at least two varieties: Ne-(carboxymethyl)lysine adducts (313), and hydroimidazolones derived from methylglyoxal and 3-deoxyglucosone. AGE-RAGE interaction stimulates multiple signals and activates important players in the pathophysiology of nephropathy, such as NAD(P)H oxidase, p21 ras, the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), extracellular signal-regulated kinase ERK 1/2 and p38, Src, and the GTPases Cdc42 and Rac, resulting in activation and translocation of nuclear transcription factors, including NF-κB (57,58, 515). Target genes of NF-κB include genes for endothelin-1 (ET-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), inter-cellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), tissue factor, thrombomodulin, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and likely, proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukins 1 and 6 (IL-1, IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), as well as RAGE itself (57, 313, 515). Moreover, RAGE has been implicated in diabetes-induced mitochondrial superoxide formation in renal cells (123). Blockade of RAGE with anti-RAGE IgG, soluble RAGE (sRAGE), the extracellular ligand that mediates the clearance of AGEs and RAGE knockout all inhibit NF-κB activation, the production of mitochondrial superoxide, and protect the kidney against deleterious effects of the diabetic milieu in experimental settings (57,58, 123, 515). More recent studies in mice indicated that blockade of RAGE may exert its renoprotective effects in the diabetic kidney in part via induction of the angiotensin (Ang) II type 2 (AT2) receptor (593).

Activation of the hexosamine pathway and consequences

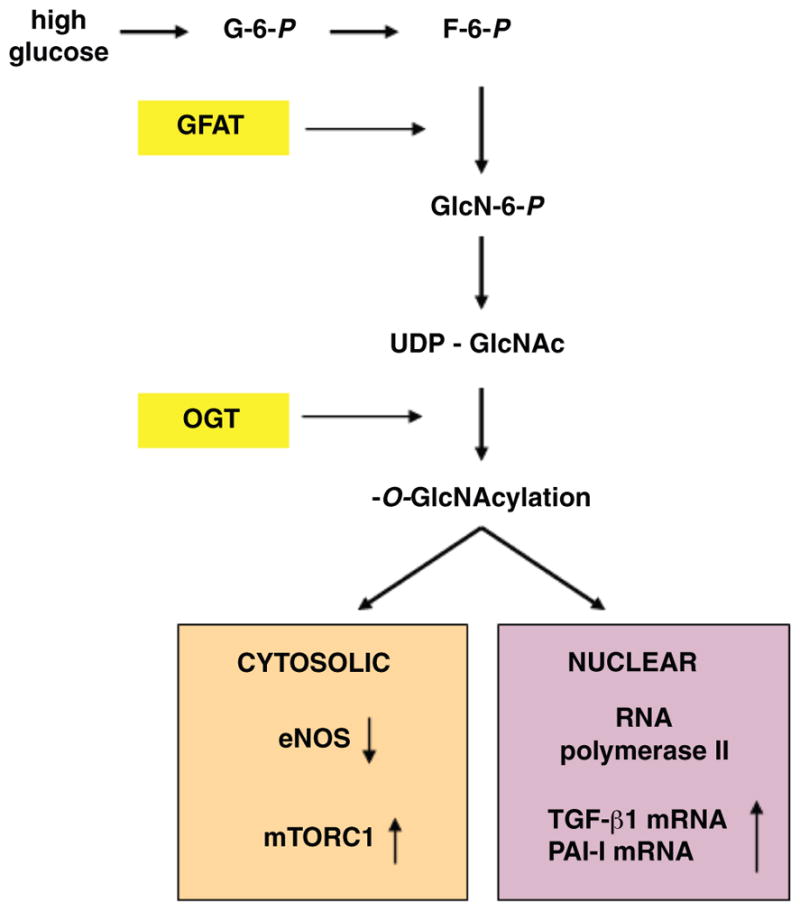

Under normoglycemic conditions, only 3% of total glucose is utilized via the hexosamine pathway. However, when the intracellular concentrations of glucose are high, fructose-6-phosphate, an intermediate in the glycolytic pathway, is partially diverted into the hexosamine pathway (see Fig. 3). Entry into the hexosamine pathway is catalyzed by the first and rate-limiting enzyme glutamine:fructose 6-phosphate (F-6-P) amidotransferase (GFAT), which converts F-6-P and glutamine to glucosamine 6-phosphate (GlcN-6-P) and glutamate. Subsequent steps metabolize GlcN-6-P to UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc). UDP-GlcNAc is a molecule of particular interest with respect to the development of diabetic complications. It serves as a substrate of O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT). This is a cytosolic and nuclear enzyme that catalyzes a reversible posttranslational protein modification, whereby GlcNAc is transferred in O-linkage to specific serine/threonine residues of numerous proteins (86, 93, 555). The sites of O-GlcNAc modification (O-GlcNAcylation) are often identical or adjacent to known phosphorylation sites, suggesting a regulatory function. Functional significance of O-GlcNAcylation has been reported for several proteins, including the transcription factors Sp1 and c-myc, as well as cytosolic and nuclear enzymes, such as glycogen synthase (GS) and RNA polymerase II [reviewed in (93)]. Sp1 was the first transcription factor identified as an O-GlcNAc-modified protein; it has multiple O-GlcNAc modification sites, and its phosphorylation on serine and threonine residues is inversely proportional to its O-GlcNAc modification (93).

Figure 3.

Activation and downstream targets of the hexosamine pathway in diabetes. When the intracellular concentrations of glucose are high, fructose-6-phosphate, an intermediate in the glycolytic pathway, is partially diverted into the hexosamine pathway. After a series of enzymatic steps glucosamine (GlcNAc) is transferred in O-linkage to specific serine/threonine residues of numerous proteins, including transcription factors as well as cytosolic and nuclear enzymes, with patho-physiological consequences in affected cells. Key enzymes in the pathway are highlighted in yellow. More detailed description is provided in the text. G-6-P, fructose-6-phosphate; F-6-P, fructose-6-phosphate; GFAT, glutamine:fructose 6-phosphate amidotransferase; GlcN-6-P, glucosamine 6-phosphate; UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase; eNOS, endothelial NO synthase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; PAI-I, plasminogen activator inhibitor-I.

The hexosamine pathway has been causally linked to up-regulation of several molecules implicated in the pathophysiology of nephropathy. Glucosamine reproduced the effect of glucose on induction of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), and blocking GFAT activity with antisense GFAT oligonucleotide or with a chemical inhibitor ameliorated high glucose/GlcN stimulation of TGF-β1 synthesis; vice versa overexpressing GFAT-induced TGF-β1 and fibronectin expression in mesangial cells incubated in 5 mM glucose (696). A more recent study (695) has suggested an ability of the hexosamine pathway to increase TGF-β1 promoter activity. Thus TGF-β1 expression seems to be dependent, at least in part, on the activity of the hexosamine pathway (see Fig. 3). The hexosamine pathway has been also implicated in diabetes-induced expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) in mesangial cells (271) and in high glucose-induced upregulation of angiotensinogen in renal tubular cells (247). Another line of evidence has shown the capability of hexosamines to activate Rho, a small GTPase protein, and its immediate downstream target, Rho kinase (ROCK), in vascular smooth muscle cells (303), a pathway recently implicated in the pathophysiology of nephropathy (316, 323, 484).

The O-linked post-translational modification has been described for endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), an enzyme responsible for endothelial NO production and essential for normal endothelial function. Du et al. (150) and Federici et al. (165) reported that hexosamine pathway-induced modification of eNOS protein interferes with its activation by phosphorylation thereby resulting in a reduced ability of eNOS to produce NO. More recent studies have also implicated the pathway in mesangial proliferation mediated by rapamycin-sensitive mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) as well as in mesangial apoptosis (272). Further studies are necessary to define the relevance of the hexosamine pathway in the diabetic kidney in vivo.

The polyol pathway

The key enzyme in this pathway, aldose reductase, catalyses reduction of toxic aldehydes in the cell to inactive alcohols. When the glucose concentration in the cell becomes too high, aldose reductase reduces glucose to sorbitol, which is later oxidized to fructose. In the process of reducing high amounts of intracellular glucose to sorbitol, the aldose reductase consumes the cofactor NADPH, which is the essential cofactor for regenerating the intracellular antioxidant, reduced glutathione. By reducing the amount of reduced glutathione, the polyol pathway increases susceptibility to intracellular oxidative stress (86). In addition, since sorbitol does not cross cell membranes, its intracellular accumulation results in osmotic stress. A small number of studies conducted in the 1990s suggested that aldose reductase inhibition could attenuate glucose-induced activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and TGF-β production in mesangial cells in vitro (261), as well as inhibit some other markers of experimental nephropathy (42, 394). Moreover, the polyol pathway has been implicated in glucose-mediated alterations in proximal tubular cell matrix generation (62, 418, 749), whereas it does not seem to contribute to tubular hypertrophy (749). Further studies are necessary to define the significance of the polyol pathway in renal pathophysiology and outcome.

Activation of protein kinase C and downstream targets

The activation of the diacylglycerol (DAG)-PKC pathway is associated with many abnormalities in retinal, cardiovascular, and renal tissues in diabetic- and insulin-resistant states (332). PKC is a family of serine/threonine kinases that consist of 12 isoforms. PKC isoforms are classified according to whether they contain domains that bind calcium or DAG, both of which positively regulate the kinase activity. Conventional PKC isoforms (α, β 1/2, and γ) bind both calcium and DAG, novel PKC isoforms (δ, ε, η, θ, and μ) bind DAG, but not calcium, and atypical PKC isoforms (ς, λ) bind neither. The activation of conventional and novel PKC isoforms require the phosphorylation of the isoforms and the presence of cofactors such as calcium and/or DAG. When phosphorylated, increases in calcium and/or DAG induce PKC translocation to the membranous compartments of the cells to elicit biological actions. Rapid and short-term increases of DAG and calcium levels are usually induced via the activation of phospholipase C. Chronic activation of conventional and novel PKC isoforms require sustained elevations of DAG, which involves the activation of phospholipase D/C or the de novo synthesis of DAG (131, 332).

In diabetes, PKC is activated via multiple mechanisms. PKC activation in diabetic tissues is linked to enhanced formation of DAG. The latter can be formed by de novo synthesis from glycolytic intermediates, dihydroxyacetone phosphate and glycerol-3-phosphate, a process stimulated by high glucose levels (86, 131). DAG can be also derived from the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositides, which are derived from the metabolism of phosphatidylcholine by phospholipase C (131). Another mechanism leading to activation of the DAG–PKC pathway involves hyperglycemia-induced increases in oxidants such as H2O2 which are known to activate PKC either directly or by increasing DAG production (442). In addition, PKC is activated as part of post-receptor signaling of vasoactive peptides known to be involved in the pathophysiology of diabetic complications, such as angiotensin (Ang) II (695) or ET-1 (141). AGEs, as another important component of the diabetic milieu, have been also shown to activate PKC, via ROS-mediated mechanisms (177). Thus, PKC activation is part of several signaling pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of the diabetic kidney.

Studies have suggested the importance of the activation of specific PKC isoforms, mainly the α, β 1/2, and δ isoforms, in causing cardiac or microvascular pathologies in diabetic animals (295, 332, 404, 489). In the kidney, activation of PKC has multiple consequences such as altered regulation of endothelial permeability, vasoconstriction, tubular transport, ECM synthesis/turnover, cell growth, angiogenesis, cytokine activation and leukocyte adhesion (156, 445). Selective inhibition of PKCβ has been shown to be nephroprotective in several models of diabetic kidney disease, which may involve effects on multiple target cells including mesangial cells, tubular cells, and antigen-presenting interstitial cells (260, 305, 308, 330, 489). First, clinical trials with a selective inhibitor of PKCβ showed beneficial short-term effects, whereas long-term kidney outcomes, assessed in patients with diabetic eye disease, were similar to placebo (638, 641). Notably, genetic variants of the PKCβ1 gene have been linked to the development of end-stage renal disease in patients with T2DM (378).

While the activation of PKC has been mostly studied as mediators of diabetes-induced cell injury, it should be noted that some isoforms, such as PKCε, may exert protective actions in the diabetic kidney (400).

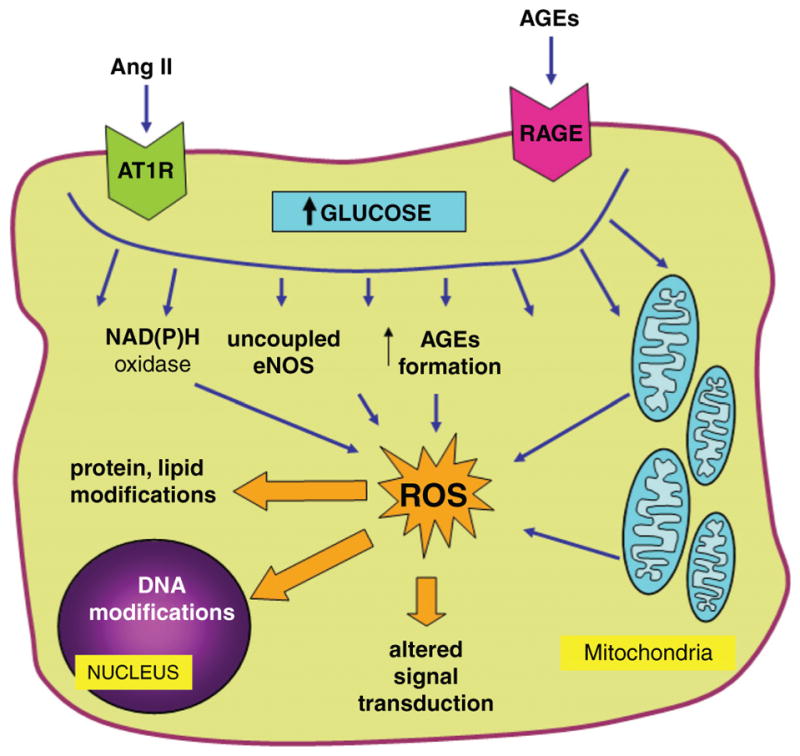

Oxidative stress

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) include free radicals such as superoxide anion (•O2−), hydroxyl anion (•OH−), and peroxyl (•RO2) and nonradical species such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydrochlorous acid (HOCl). It is important to note that there are also reactive nitrogen species produced from similar pathways, which include the radicals NO (•NO) and nitrogen dioxide (•NO2), as well as the nonradical peroxynitrite (ONOO−), nitrous oxide (HNO2), and alkyl peroxynitrates (RONOO). Of these, •O2−, •NO, H2O2, and ONOO− have been the most widely investigated in the diabetic kidney (177). Formation of ROS has been intensively studied as one of the principal mechanisms of glucose-induced cell toxicity, resulting in oxidation of important macromolecules including proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and DNA. ROS can also act as signaling molecules for growth and vasoactive factors, such as Ang II (209).

The sources of ROS in cells exposed to the diabetic milieu can be divided into mitochondrial and cytosolic, as discussed in the following and outlined in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of enhanced formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in renal cells in diabetes. High intracellular glucose, stimulation of RAGE, as well as increased activity of vasoactive and pro-growth factors, such as the renin-angiotensin system, lead to formation of cytosolic and mitochondrial ROS via multiple mechanisms. ROS alter protein, lipid and DNA structure, and act as signaling molecules in pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of diabetic complications. See text for further details. Ang II, angiotensin II; AT1R, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; AGEs, advanced glycation end products; RAGE, receptor for AGEs.

Mitochondrial source of reactive oxygen species in diabetes

Mitochondria provide energy to the cell as ATP through oxidative phosphorylation. Oxidative phosphorylation is the process by which ATP is formed as electrons are transferred from NADH or FADH2 (generated through the Krebs cycle or indirectly via glycolysis) to molecular oxygen (O2). The generation of ROS, specifically •O2−, by damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria, has been postulated as the primary initiating event in the development of diabetes complications (86, 177, 442). In diabetes, where there is an excess of fuels supplied as a result of chronic hyperglycemia feeding into the respiratory chain, it has been hypothesized that excess production of •O2− occurs via the premature collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential, which, rather than driving ATP production, leaks electrons to oxygen to form •O2−. A number of functional enzymes within the mitochondria are particularly susceptible to ROS-mediated damage, leading to altered ATP synthesis, cellular calcium dysregulation, and induction of mitochondrial permeability transition, all of which predispose the cell to necrosis or apoptosis (86, 177). However, it should be noted that these predominantly tissue culture studies (312) remain to be fully substantiated in vivo, particularly with respect to their role in nephropathy. More recent studies showed that RAGE induce cytosolic ROS and promote mitochondrial •O2− generation in diabetes. Notably, no increase in the production of mitochondrial •O2− was seen in renal cortices from gene-targeted diabetic mice lacking RAGE (123).

Cytosolic sources of reactive oxygen species in diabetes

The system of NAD(P)H oxidases seems to be, at this stage, the most important source of cytosolic ROS in the diabetic kidney. The phagocyte NADPH oxidase catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of molecular oxygen to generate superoxide anion (•O2−) which is dismuted to form H2O2 (177). The enzyme consists of two plasma membrane-associated proteins, gp91phox (the catalytic subunit) and p22phox which comprise flavocytochrome b558, and cytosolic factors, p47phox, p67phox, and the small GTPase Rac (177). Studies over the last decade have documented significant NAD(P)H-dependent ROS-producing activities, not only in phagocytes, but also in nonphagocytic cells, including kidney cells (mesangial cells, podocytes, tubular cells) (177, 604).

The family of gp91phox homologues termed Nox (for NAD(P)H oxidase) proteins consists of five members (Nox1–5), of which Nox2 is gp91phox or the neutrophil isoform (347). These oxidases are proposed to play a role in a variety of signaling events, such as cell growth, cell death or survival, oxygen sensing, and inflammatory processes. The kidney seems to be particularly susceptible to NADPH oxidase-induced oxidative damage. The isoform Nox4/Renox was cloned from the kidney and found to be highly expressed in renal tubular epithelial and mesangial cells (205). Enzyme activity and subunit expression are upregulated in response to high glucose in vascular and renal cells as well as in experimental models of diabetes and mediate diabetes-induced oxidative stress and downstream signaling, as well as renal cell structural and functional abnormalities characteristic for the diabetic state (177, 205, 235, 547, 604).

Cytosolic ROS are also formed during the formation of intracellular AGEs (177) and as a result of activation of the polyol pathway, processes discussed above in more detail. Other sources of cytosolic ROS include uncoupled eNOS (235) and xanthine oxidase (177). Further information about the individual sources of ROS and their pathophysiological roles in specific kidney compartments and cells is provided in the following sections.

In parallel with enhanced ROS generation in the diabetic environment, the cells exposed to high glucose and other components of the diabetic milieu lose their ability to fight oxidative stress. Several mechanisms of endogenous antioxidant protection have been shown to be altered in diabetic kidney as discussed in the following.

Superoxide dismutase

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is the major antioxidant enzyme for superoxide removal, which converts superoxide into H2O2 and molecular oxygen (184). The hydrogen peroxide is further detoxified to H2O by other important components of the cellular antioxidant system, catalase or glutathione peroxidase. In mammals, three SOD isoforms exist: cytoplasmic CuZnSOD (SOD1), mitochondrial MnSOD (SOD2), and extracellular CuZnSOD (SOD3, ecSOD) (177). In addition to experimental evidence, lower SOD activity has also been observed in the diabetic patients with nephropathy as compared with those without diabetic complications (177).

Overexpression of cytoplasmic Cu/ZnSOD1 in mice attenuated diabetes-induced albuminuria, glomerular hypertrophy, and ECM accumulation (142). Recent studies in mice with different susceptibility to the development of nephropathy have shown that the differences in strains may be attributable to differences in activities of SOD isoforms (189). AGE modifications could be responsible for altered activity of these enzymes in diabetic nephropathy (177).

Glutathione

The tripeptide glutathione (GSH, glutamylcysteinylglycine) is the abundant intracellular nonprotein thiol. Some 20% of intracellular glutathione is located in the mitochondria where it helps protect against mitochondrial ROS production. There are several mechanisms whereby hyperglycemia may bring about oxidative stress via changes in glutathione metabolism (86, 142, 177). Excessive glucose resulting in mitochondrial or cytoplasmic ROS generation (described above) may exhaust glutathione pool. Furthermore, as mentioned, hyperglycemia results in increased flux through the polyol pathway causing glutathione depletion.

Thioredoxin

The major thioredoxins are thioredoxin-1, a cytosolic and nuclear form, and thioredoxin-2, a mitochondrial form. Thioredoxin-1 efficiently reduces cellular ROS through thioredoxin peroxidases, which belong to a conserved family of antioxidant proteins, the peroxiredoxins. The reduced form of thioredoxin peroxidase scavenges oxidant species such as H2O2 and in the process homo- or heterodimerizes with other family members. Thioredoxin interacting protein (Txnip), also known as vitamin D3 upregulated protein-1 or thioredoxin binding protein-2, is the endogenous inhibitor of cellular thioredoxin, inactivating its antioxidative function. Hyperglycemia promotes oxidative stress, in part, through inhibition of thioredoxin activity by increased expression and activity of Txnip (566), mechanism recently demonstrated to be operating also in the diabetic kidney (12).

Detailed discussion of these exceedingly complex biochemical reactions is beyond the scope of this articles and the readers are referred to excellent reviews addressing this topic (86, 177, 475).

Glomerular Pathophysiology in Diabetes

The diabetic milieu has profound effects on glomerular function and morphology, affecting all types of glomerular cells and structures. In the following section, we will discuss diabetes-induced mechanisms of glomerular cell injury in specific cell types and their consequences for the development of proteinuria and structural changes.

Mesangial cell pathophysiology in the diabetic kidney

Although there are some exceptions to the rule, the hypertrophic phenotype prevails over the hyperplastic phenotype in diabetic glomeruli. Mesangial expansion is considered to be one of the most important structural lesions during the development of nephropathy in T1DM. The importance of mesangial expansion was proposed in seminal human biopsy studies by Mauer et al. (396) and Osterby et al. (464, 466). These studies formulated the so-called structural-functional relationship in diabetic nephropathy based on tight correlations between the degree of mesangial expansion and clinical characteristics of nephropathy, such as proteinuria, blood pressure, and the rate of decline in GFR. Mesangial expansion is determined both by mesangial cell hypertrophy and accumulation of mesangial matrix. These processes are closely related and are discussed together. Many of the following pathways are further discussed and illustrated in the section on tubular growth.

Factors driving mesangial expansion

Factors that are driving mesangial expansion are discussed in the following. We begin with growth factors and cytokines, which are stimulated by hyperglycemia, AGEs, oxidative stress, and physical forces, such as mechanical stress (211), and then discuss the role of cell-cycle regulation.

Transforming growth factor-β system

This system includes TGF-β peptides and receptors as well as Smad signaling molecules. TGF-β signals via TGF-β types I and II receptors. Upon TGF-β binding to the type II receptor on the cell surface, this complex activates the type I receptor, which then phosphorylates and activates members of the Smad family (Smad2 and Smad3). The activated Smads form oligomers with the unique co-Smad, Smad4, and rapidly translocate to the nucleus to regulate expression of target genes. Smad7 is an inhibitory Smad that regulates TGF-β signaling, preventing recruitment and phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 (364). In addition, recruitment of a complex of Smad7 with Smurf1 or Smurf2 to the type I TGF-β receptor results in receptor ubiquitination by the Smurf proteins and targets the receptor for degradation.

TGF-β is a prosclerotic factor considered to be crucial for the development of mesangial cell hypertrophy and production of ECM proteins. This factor not only stimulates genes for the components of ECM (68), but also inhibits the synthesis of MMPs, enzymes responsible for ECM degradation, and stimulates production of inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP). Thus, TGF-β is one of the major determinants of the dysbalance between production and degradation of ECM in the diabetic kidney (68). In addition, TGF-β influences the cell cycle as discussed below (706).

Numerous studies have shown that TGF-β plays a key role in the process of mesangial expansion and the development of glomerulosclerosis. Renal expression of TGF-β and other components of this system are increased in the kidney both in diabetic patients and in a variety of experimental models of diabetes (71, 191, 220, 263, 331, 575, 578, 723, 748). In addition to the components of the diabetic milieu discussed in the introductory part of this article (103), it is important to note that TGF-β is also activated by factors more typical for the metabolic environment in T2DM, such as leptin (220, 709).

TGF-β is also activated by Ang II and acts as one of the mediators of growth and prosclerotic effects of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system (RAS) (69, 119, 286, 707). Indeed, inhibitors of the RAS such as ACE inhibitors and Ang AT1 receptor blockers (ARB), or more recently with renin inhibitors (251) reduce TGF-β expression in the diabetic kidney, which is considered to be important for antifibrotic effects of these agents (70, 191). This phenomenon is discussed in more detail in a section devoted to the intrarenal activation of the RAS in the diabetic kidney. In addition, TGF-β has been show to operate downstream of other vasoactive and growth factors acting in the diabetic kidney such as ET-1 (231) or vasoconstrictor prostanoids (107, 430, 712).

The role of TGF-β as a mediator of diabetic glomerulosclerosis, as well as interstitial fibrosis (discussed in the following sections) has been documented in a number of studies using a variety of experimental approaches. A seminal study by Ziyadeh et al. (748) utilized long-term treatment with a neutralizing antibody to demonstrate that TGF-β inhibition ameliorated mesangial expansion and glomerulosclerosis in db/db mice, a model of T2DM. Interestingly, these protective effects were not associated with a significant reduction of proteinuria, suggesting that the glomerular pathology is driven by multiple factors acting on various cell types. More recently, the results by Ziyadeh et al. (748) were reproduced in studies with Smad3 knockout (KO) mice (686).

Several proteins from the TGF-β family act as endogenous antagonists of TGF-β and have also been implicated in the pathophysiology of nephropathy. For example, bone morphogenic protein-7 (BMP-7) prevents the development of nephropathy in streptozotocin (STZ)-diabetic rats (314). The small proteoglycan decorin is another endogenous inhibitor of TGF-β, acting at least in part downstream of the protective hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (315).

Connective tissue growth factor

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a 36 to 38 kDa cysteine-rich secreted protein, has been identified as a prosclerotic cytokine involved in the regulation of ECM accumulation by acting as a downstream mediator of TGF-β (91, 521). However, there is also evidence for TGF-β-independent regulation of CTGF by other components of the diabetic milieu (684). Exposure of mesangial cells to high glucose concentrations, mechanical strain, AGEs, or TGF-β leads to increased levels of CTGF gene expression and protein secretion (91, 525). In their seminal study, Riser et al. (525) examined cultured rat mesangial cells, kidney cortex, and microdissected glomeruli from diabetic db/db mice, a model of T2DM, and their control counterparts. Their results suggested that diabetes or hyperglycemia-induced CTGF upregulation is important for mesangial matrix accumulation and progressive glomerulosclerosis, acting downstream of TGF-β. Similarly, in STZ-diabetic mice, a model of T1DM, Roestenberg et al. (529) reported that CTGF expression coincided with the initiation of mesangial expansion and preceded increases in renal fibronectin and collagen IV expression.

Importantly, several observations have suggested that urinary CTGF may serve as an early biomarker and predictor of progression of nephropathy in diabetic patients. In patients with diabetes and microalbuminuria or overt diabetic nephropathy, urinary CTGF mRNA (10) or protein excretion are increased (197, 436, 522) and correlate with urinary albumin excretion and GFR. Moreover, a prospective study by Nguyen et al. has identified plasma CTGF as an independent predictor of end-stage renal disease and mortality in patients with diabetic nephropathy (437). Similarly to TGF-β, CTGF is present in the renal tubular fluid where it may act directly on tubular epithelial cells and mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition (91), a process discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Further support for a pathogenetic role of CTGF in nephropathy provided studies with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. This intervention was successful in reducing pro-teinuria and expression of genes involved in mesangial matrix expansion in mouse models of diabetes (212). In a first small and open-label phase 1 safety trial in microalbuminuric diabetic patients, the human monoclonal antibody to CTGF, FG-3019, rapidly and significantly lowered urine albumin to creatinine ratios, which warrant further prospective, randomized and blinded clinical trials (11).

Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor axis

Diabetes is associated with complex alterations of growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) secretion, activity and actions. Although a very detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this article, it is important to note that relatively abundant evidence has been amassed with respect to renal actions of these hormones and their possible contribution to the development of nephropathy. The kidneys are an important source for the synthesis of IGF-I, some of which is released into the circulation (670). GH and IGF-I have profound effects on renal growth, glomerular hemodynamics, and tubular function. Administration of IGF-I to animals promotes renal growth through a process of cellular hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and induces a rapid increase in renal blood flow and GFR together with a reduction in renal vascular resistance (163, 670). Subjects with diabetes and microalbuminuria present several alterations in the GH-IGF-IGF-binding proteins (IGFBP) system, with increased IGF-I renal levels and IGFBP-3 protease activity, increased excretion of bioactive GH, IGF-I, and IGFBP-3, but decreased circulating IGFBP-3 levels. Circulating levels of IGF-I are normal or reduced in patients with diabetes when compared with normal controls, but renal IGF-I production can be increased and contributes to the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy (670).

The most relevant evidence about the roles of the GH-IGF-I pathway in diabetic renal pathophysiology has been provided by studies with inhibitors of the system. Antagonists of the GH-IGF-I pathway, including somatostatin analogues or GH and IGF-I receptors antagonists, have been found to have beneficial effects on the diabetic kidney in animal models (340, 568). Landau et al. (340) investigated the effects of PTR-3173, a novel somatostatin analogue which exerts a prolonged inhibition of the GH-IGF axis without affecting insulin secretion, on markers of diabetic nephropathy in the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse. The treatment with PTR-3173 blunted renal and glomerular hypertrophy, albuminuria, and glomerular hyperfiltration in diabetic NOD mice. These effects were associated with the prevention of renal IGF-I accumulation.

Specific inhibitors of GH action [i.e., specific GH receptor antagonists (GHRAs)] represent another group of agents with nephroprotective potential in diabetes. Diabetic mice treated from the onset of diabetes with the GHRA, G120K-PEG, showed normalization of diabetes-induced renal hypertrophy, glomerular enlargement, and slower development of albuminuria (568). In addition, beneficial renal effects were reported even after late intervention with GHRA in NOD mice with manifest renal changes (568).

Platelet-derived growth factor

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is expressed mainly in glomerular mesangial and epithelial cells and it plays an important role in the production of ECM proteins in renal diseases. Several studies have suggested that PDGF may be involved in the pathogenesis of DN, and increased glomerular expression of this factor has been documented in models of diabetic nephropathy in vitro (633) and in vivo (306), as well as in renal biopsies from patients with nephropathy (345). However, the pathogenetic role of PDGF in diabetic nephropathy still remains to be tested in studies with selective inhibitors.

The role of cell-cycle regulation

Although diabetes-induced changes in cell-cycle regulation occurs in a variety of cell types, this topic is introduced in this section and further discussed in the section on tubular growth. Following activation, for example by growth factors, quiescent cells in G0 phase, progress through G1 phase and initiate DNA synthesis in S phase. During the G2 phase, cell growth continues and proteins are synthesized in preparation for entry into the M phase, where mitosis occurs. The process requires orchestrated activation of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK), which, after binding specific proteins (cyclins) form active complexes, and act as positive regulators of the cell cycle. The cyclin-CDK complexes are regulated by multiple phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events and by several proteins called CDK-inhibitors. Two classes of CDK-inhibitors have been identified: the INK4 family and the Cip/Kip family.

The transition from late G1 into the S phase determines the cell’s growth characteristics. G1 arrest results in hypertrophy, whereas G1 exit is associated with apoptosis. Transition from G1 to S phase results in DNA synthesis and proliferation. On entry into G1, cells normally undergo a physiologic increase in protein synthesis before S phase DNA synthesis. In hypertrophic cells, as in the kidney cells exposed to the diabetic milieu, this increase in protein content is not matched by a concurrent increase in DNA. Consequently, one mechanism underlying cellular hypertrophy is cell-cycle arrest at the G1/S checkpoint, leading to increased protein to DNA ratio (388, 573).

Mesangial cells respond to high glucose with an initial proliferation phase, which is followed by G1 arrest and hypertrophy (732). Hyperglycemia increases the expression of cyclin D1 and the activation of CDK4, evidence of cell-cycle entry (167). Importantly, exposure to high glucose increases the levels of both CDK-inhibitors p21 Cip1 and p27 Kip1 in cultured mesangial cells (709), and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to p21 Cip1 or p27 Kip1 reduce the hypertrophic effects of hyperglycemia (163). Further support for the roles of CDK inhibitors in diabetes-induced mesangial hypertrophy has been provided in studies with p21 or p27 KO mice. High glucose-induced mesangial hypertrophy was not observed in cells harvested from p21 KO or p27 KO mice. Moreover, the reconstitution of p27 Kip1 by transfection in p27 KO mesangial cells restored the hypertrophic phenotype (417, 710). In addition, both p21 Cip1 and p27 Kip1 are required for maximal mesangial cell hypertrophy induced by TGF-β (163) and hypertrophic effects of CTGF are at least in part mediated by increased expression p15 INK4, p21 Cip1, and p27 Kip1 (4).

The in vitro evidence discussed above has been reproduced in in vivo studies in experimental models of diabetic nephropathy. In STZ-diabetic mice, glomerular hypertrophy was associated with a selective increase in p21 Cip1 (338). Diabetic p21 KO mice are protected from glomerular hypertrophy and development of progressive renal failure (16). Diabetic p27 KO mice exhibit only mild mesangial expansion without glomerular hypertrophy, despite increases in glomerular TGF-β (32, 708). In summary, these cell culture and experimental models show that p21 Cip1 and p27 Kip1 play a critical role in mediating diabetes-associated glomerular hypertrophy and the consequential increase in matrix proteins, associated with the deterioration in renal function. These pathways are further discussed and illustrated in the section on tubular growth.

Notably, an influence of the presence of ECM proteins on the response of mesangial cells to diabetes has been indicated in a recent study in STZ-diabetic mice. Using KO mice for type VIII collagen, Hopfer et al. linked mesangial expansion and cellularity, ECM expansion and albuminuria to the expression of type VIII collagen which is enhanced in this model (243).

Changes in the Glomerular Filtration Barrier in the Diabetic Kidney

The glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) is composed of glomerular endothelial cells (GEC), the glomerular basement membrane, and podocytes (glomerular epithelial cells). All three components of the barrier undergo changes in diabetes and contribute both to the structural glomerular alterations and changes in the permeability to macromolecules. In addition to other functions, the integrity of the GFB determines the extent to which albumin and other proteins will be filtered into the urinary space and, thereby, contributes to the development of albuminuria/proteinuria, a hallmark of diabetic nephropathy. Figure 5 illustrates and summarizes diabetes-induced changes in the GFB.

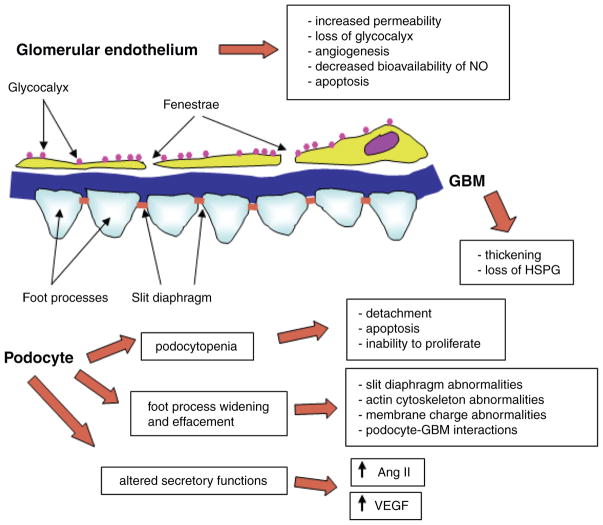

Figure 5.

Diabetes-induced alterations of glomerular filtration barrier. The schematic presentation describes major consequences of diabetes-induced changes in glomerular endothelial cells, glomerular basement membrane, and podocytes, as discussed in more detail in the text.

The GFB contributes to the impermeability to macromolecules by size and charge selectivity. Under physiological conditions, low molecular weight proteins (≤40 kDa) are essentially freely filtered, whereas, high molecular weight proteins (≥100 kDa) are almost completely restricted (125, 390). The molecular weight of albumin is 69 kDa, that is, of borderline size. In patients with diabetes and low-grade albumin excretion (microalbuminuria), no changes in size selectivity, determined mainly by the radius of glomerular endothelial pores, have been reported (550), suggesting a possible role for alterations in the charge barrier at the early stages of microalbuminuria. The charge barrier is formed by anionic sites within the GBM, on podocytes and the endothelial glycocalyx. As the disease progresses, anatomical derangements of the GFB result in gradual loss of selectivity.

Changes in the glomerular endothelium in the diabetic kidney

The changes in the glomerular endothelium are similar to the well-described generalized endothelial dysfunction in diabetes, including reduced bioavailability of NO, impaired endothelium-dependent regulation of vascular tone, upregulation of adhesion molecules, development of a pro-thrombotic phenotype and increased permeability (203, 318, 500, 551). These changes are not specific for GEC, but are applicable to the entire renal vascular tree.

Unlike other capillaries, glomerular capillaries have a high permeability to water (hydraulic conductivity), yet, like other capillaries, they are relatively impermeable to macromolecules. GEC are highly specialized cells with regions of attenuated cytoplasm punctuated by numerous fenestrae, circular transcellular pores 60 to 80 nm in diameter (36). The glycocalyx is a layer on the luminal surface of GEC, largely composed of glycoproteins and proteoglycans with adsorbed plasma proteins. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans (HSPGs) may be responsible for the negative charge characteristics of the glycocalyx (36). Relevant for the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy, ROS have been shown to disrupt the glycocalyx (230). In diabetes, a specific assessment of structural changes in GEC and the associated glycocalyx has not been performed. However, indirect evidence supports the notion that abnormalities of the glycocalyx exist and may be relevant. For example, total systemic glycocalyx volume is reduced by acute hyperglycemia in humans (440). Furthermore, patients with T1DM have decreased systemic glycocalyx volume, which correlates with the presence of microalbuminuria (439).

Impaired activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and of nitric oxide

eNOS and eNOS-derived NO are crucial molecules for endothelial function and integrity. NO acts as a potent vasodilator and as a molecule with potent anti-thrombotic and anti-growth properties in the vasculature (318). Earlier studies suggested several direct mechanisms whereby the diabetic milieu antagonizes NO bioavailability. These mechanisms include NO quenching by AGEs (89, 673) or ROS (235), and NO capture by glucose (82).

More recent studies revealed a spectrum of mechanisms related to posttranslational alterations of eNOS molecules in diabetes. To function as an endothelial NO-producing enzyme, eNOS requires a battery of co-factors, posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation and dimerization, protein-protein interactions, and subcellular targeting (207). Phosphorylation of eNOS on Ser1177 by several serine/threonine kinases, such as Akt (protein kinase B) (143, 192) or protein kinase A (PKA) (94), in response to a variety of physiological stimuli, is a critical control step for NO production by the enzyme. This process enhances the rate of electron flux from the reductase to the oxygenase domain of eNOS, and reduces the calcium requirements for the enzyme, thus increasing NO synthesis (398). Also the formation of a homodimer is crucial for NO production by eNOS (229, 350), creating high affinity binding sites for the NOS substrate L-arginine, and enabling electron transfer from the reductase domain of one NOS monomer to the oxygenase domain of the other (541). Finally, activation of eNOS is not only dependent on phosphorylation by upstream kinases and conformational changes, but is also determined by its specific subcellular localization with the activatable enzyme being localized within the plasma membrane.

As mentioned in the “General mechanisms of glucose-induced cell injury” section, hexosamine pathway-induced modification of eNOS molecule in vitro interferes with its stimulatory phosphorylation resulting in a reduced ability of eNOS to produce NO (150, 165). To address these issues in in vivo settings, Komers et al. (326) analyzed renal cortical samples from control and STZ-diabetic rats, and described impaired eNOS dimerization, membrane targeting, and stimulatory phosphorylation at Ser1177 in diabetic samples despite of similar whole cell eNOS expression in diabetic and control animals. These findings further suggest that a process called “eNOS uncoupling” operates also in the diabetic kidney. During this process, electron transfer within the active site of eNOS becomes “uncoupled” from L-arginine oxidation resulting in reduction of molecular oxygen to superoxide (669, 720). Thus, eNOS can become a ROS producing enzyme in sharp contrast to its protective role as a machinery for production of protective NO. Indeed, renal production of ROS has been shown to be attenuated by L-arginine-analogues (547) that act as NOS inhibitors. The mechanisms of uncoupling are currently being investigated, but well-described diabetes-induced deficiency in co-factors, such as tetrahydrobiopterin (402, 503), necessary for conformational changes of eNOS allowing NO production, are likely to play a role.

Moreover, as postulated by Nakagawa et al. (423) high glucose-induced posttranslational changes in eNOS may be responsible for uncoupling of VEGF actions from eNOS, allowing unhindered growth and vasoactive signaling of VEGF (discussed in detail below) without parallel activation of protective eNOS-derived NO production. VEGF normally stimulates endothelial NO release and acts in concert with elevated NO levels as a trophic factor for vascular endothelium. The increased NO derived from the endothelial cell acts as an inhibitory factor that prevents excess endothelial cell proliferation, mesangial or vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, and macrophage infiltration. In the setting of reduced NO bioavailability, high levels of VEGF lead to excessive endothelial cell proliferation, stimulation of macrophage chemotaxis, and mesangial or vascular smooth muscle cell activation.

Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in the early and later stages of the diabetic kidney

Several kidney biopsy studies have confirmed increased glomerular vascularity and endothelial cell proliferation at early stages of diabetic nephropathy (465). VEGF, a pro-angiogenic factor, is prominently produced by podocytes (122). VEGF may affect podocyte function in an autocrine fashion (via VEGFR1) (106). VEGF protein also crosses the GBM and acts on GEC (via VEGFR1 and VEGFR2) to promote endothelial cell survival and to induce the formation of fenestrae, which enhance glomerular endothelial permeability. VEGF expression is increased at early stages of nephropathy, and has been implicated in diabetic renal patho-physiology, and in accord with its actions, as a mediator of albuminuria or even structural changes (122, 134). Indeed, inhibition of VEGF by a variety of means reduces albuminuria in diabetic rodents (134, 337, 603).

However, the role VEGF and angiogenesis in the development of diabetic kidney disease, even albuminuria is more complex. VEGF may be elevated in the early phases of the diabetic kidney, but it may not be maintained as more chronic fibrotic changes occur in the kidney, and VEGF may decrease in the advanced stages of the disease. In a remnant kidney model, VEGF levels are reduced, correlating with the progression of renal damage (294). In human as well as experimental diabetic nephropathy, more advanced stages are also associated with lower VEGF expression (34, 195, 238, 372). These observations suggest that the upregulation of VEGF in early stages of diabetic nephropathy may provide a mechanism for the initial progression of the disease, leading to excessive blood vessel formation and albuminuria. The decline of VEGF in the later phase of diabetic nephropathy may reflect a loss of endogenous VEGF due to the disruption of podocytes and tubular cells in chronic kidney damage. In fact, at later stages of chronic kidney disease, VEGF is currently considered to be a protective factor with beneficial effects on glomerular endothelium, podocyte viability, and, as described in the remnant kidney models and in diabetic patients, on the peritubular network of capillaries (372), preventing the progression of interstitial fibrosis.

Role of inhibitors of angiogenesis and angiopoietins in the diabetic kidney

The pathophysiological roles of angiogenic factors in the diabetic kidney are further supported by studies focusing on endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis. These molecules originate as cleavage products of ECM proteins (tumstatin and endostatin) or plasminogen (angiostatin) and specifically target endothelial cells and inhibit their proliferation, survival, migration, and sprouting (218, 459, 460). The levels of these proteins are dramatically decreased in the kidney of STZ-diabetic rats, most likely due to decreased activity of MMPs [see section “Glomerular pathophysiology in the diabetic kidney” and (740)]. Administration of tumstatin (a cleavage product of collagen IV), endostatin (a cleavage product of collagen XVIII), or angiostatin has been shown to reduce glomerular hypertrophy, hyperfiltration, albuminuria, mesangial matrix expansion, ECM accumulation, endothelial cell proliferation, and monocyte/macrophage infiltration in STZ-induced diabetic mice (255, 724, 740) in parallel with the suppression of multiple molecular markers of nephropathy. The treatments also increased nephrin expression (255, 724) and enhanced the levels of pigment epithelium-derived factor, another endogenous antiangiogenic factor (740). Similar renoprotective effects have been observed in STZ-diabetic mice treated with vasohibin-1, an endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor that is, unlike the angiostatins discussed above, induced in endothelial cells by proangiogenic factors (428).

The studies with endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors should be also interpreted with caution. Despite impressive effects of these molecules on a variety of functional, structural and molecular markers of nephropathy, these studies were conducted only for several weeks in STZ-diabetic mice known to be relatively resistant to the development of structural changes characteristic of diabetic nephropathy. Although those studies suggest beneficial effects of angiogenesis inhibition at early stages of nephropathy, their long-term nephroprotective effects, and consequently the role of angiogenesis later in the course of the disease, remain to be established. Moreover, observed beneficial effects of angiogenesis inhibitors in mesangial cells and podocytes suggest involvement of additional, less understood, effects unrelated to modulation of angiogenesis.

Angiopoietins are another family of vascular growth factors that have been implicated in the pathophysiology of nephropathy. The best-studied are angiopoietin 1 (Ang-1) and Ang-2. During normal development, they are considered critical for vascular differentiation through angiogenesis, the process of growth and remodeling of existing vessels. In mature organisms, angiopoietins are involved in maintenance and turnover of blood vessels (715). Ang-1 causes enhanced endothelial survival and endothelial cell stabilization, whereas Ang-2 acts as a natural antagonist of Ang-1 (310). The in vivo biologic effects of the angiopoietins also depend on ambient levels of VEGF-A (715). Angiopoietins seem to be linked to nephrin expression, since Ang-2 overexpression in non-diabetic mice leads to downregulation of nephrin (132). Experimental models of T1DM are associated with altered renal expression of angiopoietins. Rizkalla et al. (527) reported that in STZ-diabetic rats whole-kidney Ang-1 and Ang-2 mRNA and protein levels rose at 4 weeks, but at 8 weeks, Ang-1 levels were lower than those in nondiabetic controls, whereas Ang-2 remained elevated. Ang-1 was immunolocalized in diabetic kidney tubules, whereas Ang-2 was prominent in glomerular endothelia and podocytes. Yamamoto et al. (724) also reported renal upregulation of Ang-2 in STZ-diabetic mice. In accordance with this in vivo evidence in models of diabetes, more recent in vitro studies in endothelial cells identified mechanisms of high glucose-induced Ang-2 expression (727). These observations suggest that a decreased ratio of Ang-1/Ang-2 might play a role in the pathobiology of glomerular disease in diabetic nephropathy. However, considering the above discussed effects of angiogenesis inhibitors in the diabetic kidney, the pathophysiological roles of Ang-1/Ang-2 remain rather murky. It is also possible, that the primary target of these molecules is not the GEC but the podocytes.

Other factors influencing glomerular endothelial permeability in diabetes

Glomerular endothelial permeability can also be increased by proinflammatory cytokines and adipokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6 and leptin, that is, factors more typical for T2DM [reviewed in (546)]. In contrast, adiponectin, unlike other adipokines, appears to have protective effects in the vasculature by reducing endothelial cell activation and inflammation, in addition to protective and antiproteinuric effects on podocytes (577).

The glomerular basement membrane in the diabetic kidney

The normal GBM is a 300- to 400-nm thick structure consisting predominantly of type IV collagen, laminin, nidogen, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). In T1DM, GBM thickening occurs early in the course of the disease, long before the development of microalbuminuria. Thickening of the capillary basement membrane has been observed in other vascular beds in patients with T1DM and does not seem to be specific for the kidney (149, 392). The thickening of the GBM is due to the accumulation of ECM, which originates most likely in the podocyte (see Fig. 6).

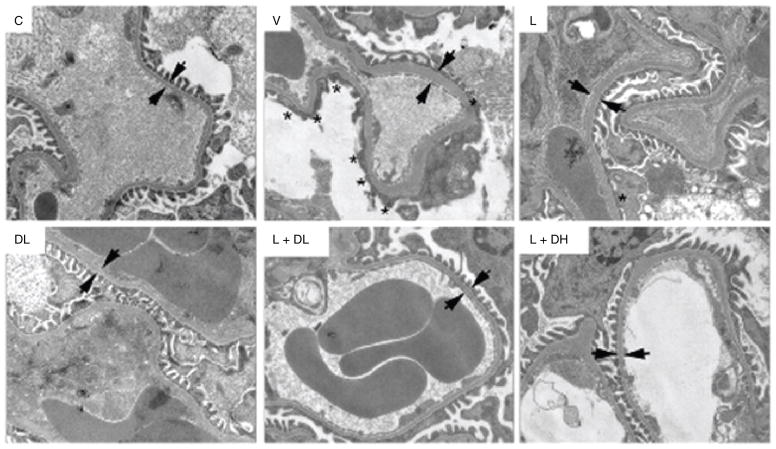

Figure 6.

Podocyte foot process effacement and glomerular basement membrane (GBM) thickening in experimental diabetes. Transmission electron microscopy was used to investigate the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) in normal (C) and STZ-diabetic DBA/2J mice (V, L, DL, L + DL, and L + DH). Compare the appearance of the GFB in normal (C) and diabetic mice (V), and the effects of nephroprotective treatments [L, DL, L + DL, and L + DH; for details on treatments see (741)]. Stars indicate the areas of podocyte foot process effacement; arrow pairs point to both sides of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). Adapted with permission from (741).

The GBM may constitute a charge barrier, due to its HSPG content. The evidence for a role of HSPG in the diabetic kidney remains controversial with equally persuasive reports supporting a role of loss of HSPG in diabetes (136, 404, 508, 586, 610) or arguing against it (666, 700, 701).

Paradoxically, diabetes-induced increases in GBM thickness might be expected to reduce protein transit, but it is associated with proteinuria. However, as postulated by Jefferson and coworkers (273), the GBM thickening occurs in an irregular manner with areas of thinned GBM with presumably enhanced permeability for proteins. Moreover, altered GBM may affect the adjacent cellular elements, reducing cell binding and promoting podocyte detachment (see below).

Podocyte pathophysiology in diabetes

Podocytes are terminally differentiated and highly specialized cells. They line the urinary side of the GBM and function as a fine filter contributing to ultimate size-selectivity and permitting permeability to molecules smaller than albumin. They also synthesize components of the GBM and counteract capillary hydrostatic pressure. The podocyte is composed of the cell body and interdigitating foot processes. The narrow gaps (30–40 nm) between neighboring processes are bridged by the glomerular slit diaphragm. This crucial structure is a highly specialized gap junction with small pores, permeable to water and solutes but relatively impermeable to plasma proteins. The shape of podocytes is supported by an actin cytoskeleton, which allows the podocyte to dynamically change its shape. Podocytes are anchored to the GBM by integrins and α- and β-dystroglycans. Similar to GEC and GBM, podocytes are also negatively charged on their apical membrane domain owing to surface anionic proteins such as podocalyxin, podoplanin, and podoendin. The negative charge helps limit passage of negatively charged molecules (like albumin). However, podocytes also serve as a size barrier to proteins, predominantly due to the properties of the slit diaphragm.

When exposed to the diabetic milieu, podocytes undergo a spectrum of changes that ultimately contribute to the development of proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. These include a reduction in podocyte number (podocytopenia), foot process widening and effacement, and altered secretory functions. These processes are closely linked, but will be, for better clarity, discussed separately and are summarized in Figure 5. Importantly, kidney biopsies from Pima Indians with type II diabetes suggested that podocyte loss contributes to the progression of diabetic nephropathy (354, 355, 468).

Reduction in podocyte number (podocytopenia)

Several mechanisms have been implicated in podocyte loss in the diabetic kidney as outlined in the following.

Podocyte detachment

The appearance of podocytes in the urine (podocyturia), which has been described in 53% of microalbuminuric and 80% of macroalbuminuric patients with T2DM, while being absent in subjects with normal albumin excretion (424, 488), has been considered to be a persuasive in vivo indicator of podocyte detachment in the diabetic kidney. It has been proposed that this abnormality occurs due to reduced expression of the α3β1 integrin, the predominant integrin tethering the podocyte to the GBM (102).

Podocyte apoptosis

There is increasing and relatively abundant evidence implicating apoptosis of podocytes as another cause of podocytopenia in diabetes. Several mechanisms might underlie podocyte apoptosis in diabetes. Studies by Susztak et al. (604) have implicated high glucose-induced oxidative stress and proapoptotic p38 MAPK signaling in this process. Importantly, this study demonstrated that apoptosis preceded podocyte depletion and coincided with the onset of albuminuria. It should be noted, however, that early activation of p38 MAPK has also been associated with maintenance of the actin cytoskeleton in diabetic podocytes, and its loss correlated with progression of proteinuria (130). Other factors operating in the diabetic kidney, such as TGF-β (554, 683) or activation of RAS (151), have also been shown to induce podocyte apoptosis. Other studies have implicated a stimulation of RAGE, which is overexpressed on podocytes in experimental T2DM, in proapoptotic signaling (699).

More recently, Isermann et al. (258) reported interesting findings implicating activated protein C (APC) formation in several alterations in the diabetic kidney. Protein C is an antithrombotic system, regulated by endothelial thrombomodulin. Plasma protein C activity is reduced in diabetic patients (682), but with no clear link to the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy. Isermann and colleagues described a lower activity of a new pathway involving thrombomodulin-dependent APC formation in the diabetic kidney, resulting in attenuated cytoprotection in renal cells and enhanced glomerular apoptosis including podocytes. APC prevented the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway via the protease-activated receptor PAR-1 and the endothelial protein C receptor EPCR in glucose-stressed cells. In vivo, maintaining high APC levels during long-term diabetes protected against diabetic nephropathy in mice (258).

Activation of the Notch signaling pathway has been the most recent addition to a spectrum of mechanisms underlying podocyte apoptosis in diabetes. Notch proteins and numerous components of their down-stream signaling pathway are known to play a crucial role in mammalian kidney development. However, Notch1 is practically undetectable in the mature kidney. Niranjan et al. (441) have reported the expression of genes in the Notch pathway in mature podocytes in humans with diabetic nephropathy and in mice with STZ-induced diabetes. Moreover, expression of ICN1, a Notch intracellular domain, in podocytes resulted in apoptosis in vitro and led to podocyte loss, albuminuria, and glomerulosclerosis in vivo. Conversely, genetic or pharmacological inhibition of Notch signaling prevented podocyte apoptosis and albuminuria. Most recently, Lin et al. (370) extended these observations and showed that, in addition to the antiapoptotic effect, inhibition of Notch1 abrogated high glucose-induced VEGF synthesis and nephrin loss in podocytes, with a beneficial effect on proteinuria in diabetic animals.

Inability to proliferate and restore podocyte number

In contrast to mesangial cells, mature podocytes do not actively synthesize DNA nor proliferate under normal conditions (480). In the diabetic kidney, where podocytes undergo detachment or apoptosis, the relative inability of these cells to proliferate may lead to an eventual decline in number and become a contributing factor for the reduced podocyte number. As shown in several studies, high expression of CDK inhibitors may be responsible for this phenomenon (573).

High expression of CDK inhibitors has also been linked to another diabetes-induced podocytic change, namely hypertrophy (708). Under diabetic conditions, podocytes undergo hypertrophic changes like mesangial cells, resulting in increased cell size (517). The high glucose-induced podocyte hypertrophy can be ameliorated by Ang II AT1 receptor blockade, suggesting the involvement of RAS activation (365). Downstream effectors may include parathyroid hormone-related protein, which induces hypertrophy in podocytes via TGF-β1 and p27 Kip1 (530). In addition to high glucose, cyclic mechanical stretch, as a result of elevated intraglomerular pressure and impaired autoregulation (see below), can induce podocyte hypertrophy (487). The pathophysiological consequences of the increased size of podocytes are not clear. However, as shown by Wolf et al., the protective effect against the development of nephropathy in STZ-diabetic mice by deletion of the CDK inhibitor p27 Kip1 was associated with reduced podocyte hypertrophy and collagen type IV and laminin expression (708). Additional studies indicated that exposure of podocytes in culture to AGE-modified bovine serum albumin (AGE-BSA) induces cell-cycle arrest and cell hypertrophy by a mechanism that involves upregulation of p27 Kip1 (535). More recently, Bondeva et al. exposed differentiated mouse podocytes in culture to AGE-BSA. Using differential display and real-time PCR analyses they observed a downregulation of neuropilin-1 and confirmed a reduction in neuropilin-1 expression in glomeruli of diabetic db/db mice and in renal biopsies from patients with diabetic nephropathy compared to transplant donors (66). Additional in vitro studies indicated that AGE-BSA inhibited podocyte migration by down-regulating neuropilin-1. The authors proposed that decreased podocyte migration could lead to adherence of uncovered areas of the glomerular basement membrane to Bowman’s capsule thereby contributing to focal glomerulosclerosis.

Podocyte foot process widening and effacement

Foot process effacement is a result of retraction, widening, and shortening of the podocyte foot processes (see Fig. 6). The retraction results in large areas of flattened epithelium covering the capillary loop. This leads to a decrease in slit diaphragm pores per unit of length of GBM, causing a reduction in filtration surface. However, as postulated by Jefferson et al. (273), focal epithelial defects may allow increased protein flux across these denuded areas. This may be further facilitated by defects in slit diaphragm protein composition. This phenomenon is not specific for the diabetic kidney, and proteinuria may occur without effacement (730). Conversely, effacement is not always associated with proteinuria (273). Mundel and Shankland (419) proposed that the underlying mechanisms leading to foot process effacement include (1) changes in slit diaphragm-associated proteins, (2) actin cytoskeleton abnormalities, (3) alterations in the negative apical membrane domain of podocytes, and (4) interference with podocyte-GBM interaction.

Slit diaphragm abnormalities

The slit diaphragm, which bridges adjacent foot processes derived from different podocytes, functions as the ultimate molecular size filter. Several podocyte-specific proteins, such as nephrin, NEPH1, P-cadherin, and FAT-1 have been located at this region, whereas CD2AP, podocin, and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) are found in the slit diaphragm inserted region of the foot process [reviewed in (365)]. The relevance of these proteins has been documented by detection of foot process effacements, often associated with proteinuria, in patients with mutations of these genes or experimental models with targeted deletion or administration of antibodies to some of these molecules (365).

Proteinuria is a hallmark of diabetic nephropathy. Consequently, studies have focused on the changes in slit diaphragm-associated molecules in diabetic nephropathy. Thus far, nephrin is the best studied slit diaphragm protein in the diabetic context. Bonnet et al. (67) demonstrated a reduction in nephrin mRNA and protein expression in STZ-induced diabetic spontaneously hypertensive rats at 32 weeks after diabetes induction. These experimental findings are in accord with observations in kidney biopsies derived from patients with nephropathy and T1DM or T2DM (148). These changes in nephrin expression have been linked to activation of PKCα (403) and/or the RAS (67, 323, 344). Similar changes in nephrin expression were observed in cultured podocytes exposed to glycated albumin and Ang II (148). In contrast, Aaltonen et al. (1) showed an increase in nephrin mRNA levels in STZ-diabetic rats and in nonobese diabetic mice even before the development of significant albuminuria. In another study, nephrin protein expression was increased in renal cortex of db/db mice (603), whereas others found no changes in renal cortical nephrin expression in diabetes (337). The reasons for the disparate findings may be due to differences in duration of diabetes, the possibility of a biphasic response in nephrin expression and the influence of confounding factors, like hypertension.

Compared to nephrin, there have been relatively fewer investigations on the changes of other slit diaphragm proteins. P-cadherin mRNA and protein expression were reduced in diabetic glomeruli and in podocytes exposed to high glucose, a process mediated by PKC (722). Another study revealed decreases in ZO-1 protein expression in glomeruli of animal models of T1DM and T2DM and in high glucose-stimulated podocytes (520). In comparison, the expression of CD2AP and podocin has been reported to be unchanged under diabetic conditions (51, 329).

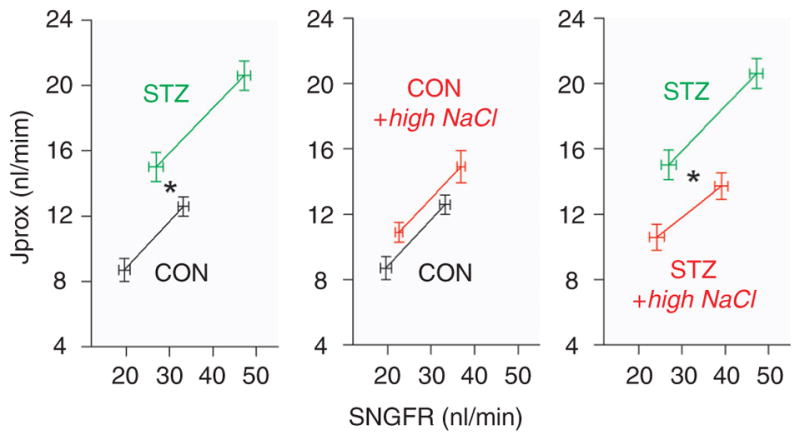

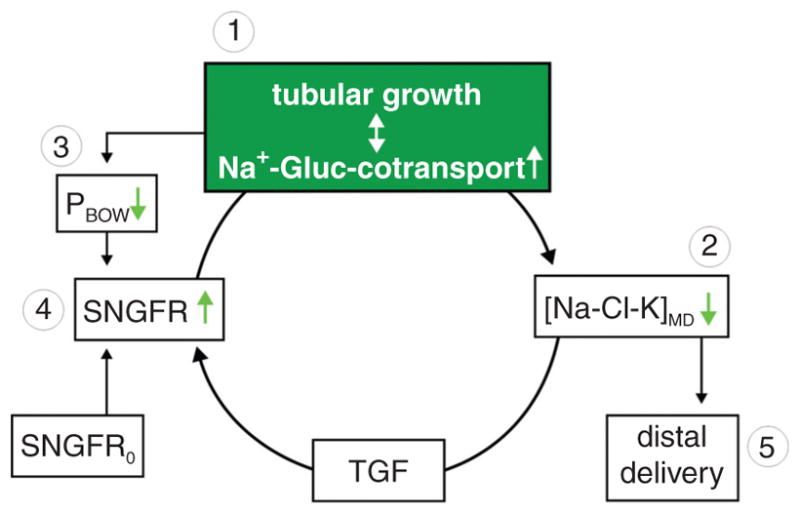

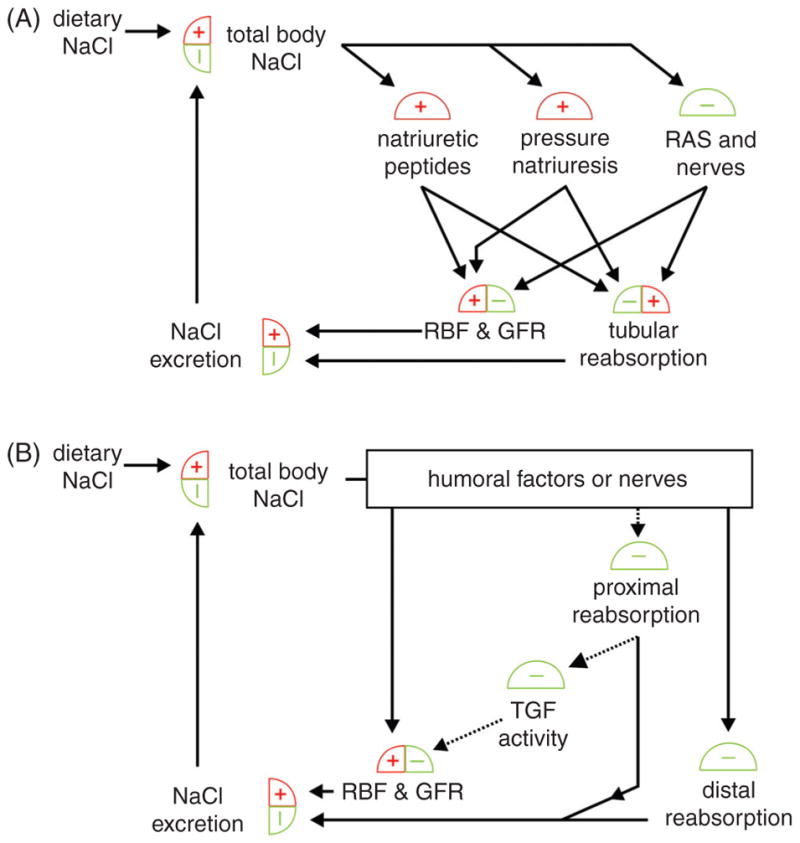

Actin cytoskeleton abnormalities