Abstract

Objectives

The present research was motivated by providing new insight into early pregnancies with a chorionic bump diagnosis in first-trimester sonography and its impact on live birth rate.

Methods

To determine the rate of CB, first trimester sonograms of pregnant women referring to Akbarabadi Hospital, which is a treatment and training center affiliated to Iran University of Medical Sciences as well as those referring to a private center were analyzed. The total number of transvaginal sonographies performed was 1900 cases from whom 8 cases of CB were detected. The chorionic bump size and number and history of infertility or coagulation disorders were considered as our independent variables and multiple gestation with pregnancy outcome as dependent ones.

Results

Overall, the prevalence rate of CB was 0.4% (4 per 1000), with 8 patients diagnosed with CB from 1900 the first trimester pregnant women. Of 8 pregnant women, 5 showed live birth (62.5%) and 3 experienced fetal demise (37.5%). The chorionic bumps ranged in size from 0.1 cc to 1.8 cc (average, 0.73 cc). No significant relationship was found between history of smoking, coagulopathy, infertility, multiple gestation and the size of CB.

Conclusions

The main finding was that the frequency of live birth in our sample was 62.5% (5 from 8). The clinical inference is that a chorionic bump on first-trimester sonography does not definitely guarantee a secure prediction. The correlation between bump size and pregnancy outcome is not clear, which warrants further research.

Keywords: Chorionic bump, First trimester, Live birth rate, Sonography

Introduction

A Chorionic Bump (CB), which has been identified as “an irregular, convex bulge from the choriodecidual surface into the first-trimester gestational sac,” was first reported by Harris et al. in 2006 as an important finding in early first trimester pregnancy sonography as a risk factor for pregnancy loss, with live birth rate of less than 50% [1]. The cause of CB remains unclear and several assumptions have been proposed as to whether it is the cause of early demise or follows it [2]. The chorionic bump might represent the following: a hematoma, an area of hemorrhage, a non-embryonic gestation, or a demise of an embryo in a twin pregnancy [2,5]. No clear pattern is detected using color and power Doppler examination. From 2006 to 2015, several studies have been conducted on CB including Arleo et al. [3] who provided a systematic review and meta-analysis of CB in pregnant patients and associated live birth rate, Harris et al. [1] who studied a prospective cohort, Sana et al. [4] who carried out a case–control study, as well as a few case reports [5,6,7,8] and Joseph et al. [9] who published a retrospective cohort.

Although CB is an uncommon finding, its incidence rate has been reported to be 1.5–7 per 1000 [4], impressively 23 per 1000 by Joseph et al. who studied first trimester chorionic bump associated with fetal aneuploidy in a high risk population [9]. The viable pregnancy outcome rate in the first trimester is reported between less than 50% to 65% and an unexpected 83% if other factors of pregnancy are normal [2,4].

Although it is considered as a risk factor in loss of pregnancy, many radiologists and gynecologists may not be familiar with it. Thus, the present research was motivated by providing new insight into early pregnancies with a CB diagnosis in first-trimester sonography and its impact on live birth rate.

Materials and methods

This study is a retrospective report on a small case series of 8. The study is approved by Institutional Review Board. For determination of CB rate, analysis of first trimester sonograms of pregnant women referring to Akbarabadi Hospital, which is a treatment and training center affiliated to Iran University of Medical Sciences as well as those referring to a private center was conducted (≈ 5 per day). All sonogra-phies were performed by the same radiologist who is also a university lecturer.

Transvaginal sonography was performed considering such factors as confirming or rejection of intrauterine pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, vaginal bleeding and pain also dating.

Transvaginal sonography was performed for the first trimester pregnant women at Akbarabadi Hospital, 5 per day, 30 per week, 120 cases per month, amounting to a total number of 1440 plus 460 cases performed at the private center in the evening. The total number of transvaginal sonographies performed was 1900 cases from whom 8 cases of CB were identified.

Follow-up sonography once or twice a week, or more often if the gynecologist indicated, was considered for CB patients.

Patients who were at least 18 years old with diagnosis of chorionic bump in first trimester sonography were qualified as our study cases. Patients with miscarriage or nonviable pregnancy outcome, systemic diseases, coagulopathy, and multiple gestations were not excluded.

The medical records were completed in the form of questionnaire by sonographist, including details such has name, age, date of conception, the volume of CB, mean sac diameter (MSD), fetal heart rate (FHR), crown-rump length (CRL), vaginal bleeding, experience of a previous nonviable pregnancy outcome and its cause, coagulopathy or systemic diseases, smoking, diabetes, description of infertility, and finally pregnancy outcome as well as delivery mode (Vaginal delivery or Cesarean).

We have some limitations in our study. For example, due to the recent introduction of CB, and the possibility of failure to diagnose CB or mistaking it with subchorionic hemorrhage only the sonographies performed by the university lecturer were included in the data and those performed by residents were excluded. Also, it should be noted that considering low incidence in both patients and literature, studies on CB have no obvious exclusion criteria so all patients with chorionic bump with at least 18 years old were included in the study, even with previous history of abortion or misoprostol usage as our limitation in study.

Transvaginal sonography was performed with Samsung Medison SW80 at Akbarabadi Hospital and Medison V20 at the private center.3-D measurement of chorionic bump was performed with electronic calipers to access its volume (elliptical volume formula: length × width × height × 0.52), and then, if present, was registered on serial sonograms. Statistical methods used for data analyzation were as follows: To define the study patient population, averages and ranges were calculated for continuous variables, and numbers and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. The statistical analysis was performed using multivariate logistic regressions to investigate the relation between each independent variable and presence of a live birth. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

The incidence rate of CB was 0.4% (4 per 1000), with 8 patients diagnosed with CB from 1900 first trimester pregnant women. Table 1 shows the characteristics and sonog-raphy findings for these 8 patients.

Table 1.

The characteristics and sonography findings for the 8 patients.

| Patient | Age | Age of Gestation upon diagnosis | Bump volume (cc) | MSDa(mm) | CRLb(mm) | Yolk sac | Fetal embryo | FHRc | Vaginal bleeding | Prior nonviable outcome | Cause of prior poor outcome | Coagulopathy | Systemic disease | Smoking infertility | Pregnancy outcome | Type of delivery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | 8 weeks | 0.5 | 26 | 3.5 | + | Yes | NO | – | 3 | bicornuate | – | hypothyroidy | – | – | Demise at 10 weeks | – |

| 2 | 40 | 6 weeks | 0.2 | 12 | – | + | NO | NO | + | – g | – | – | – | – | – | demise at 6 weeks | – |

| 3 | 23 | 6 weeks | 0.1 | 11 | – | + | NO | NO | – | 1 | Molar pregnancy | – | – | – | – | Viable 37 weeks | NVDd |

| 4 | 33 | 5 weeks + 4 days | 0.6 | 9.5 | – | + | NO | NO | – | – | – | – | hypothyroidy | – | – | Viable 38 weeks | C/Se |

| 5 | 28 | 6 weeks 9 weeks |

1.8f | 12f | – 21 |

+ | NO Yes |

NO | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Viable 38 weeks | C/S |

| 6 | 26 | 5 weeks + 6 days 6 weeks + 6 days | 0.3 0.8 |

14.5 19 |

3 8 | + | Yes | Bradycardy Normal FHR |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | Viable 40 weeks | NVD |

| 7 | 35 | 7 weeks + 1 day | 0.9 | 20 | – | + | NO | NO | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Viable 38 weeks | C/S |

| 8 | 30 | 8 weeks + 5 days | 1.5 | 29 | 6 | + | Yes | NO | – | – | trauma | – | – | – | – | demise at 9 weeks | – |

a Mean sac diameter (MSD).

b Crown-rump length (CRL).

c Fetal heart rate (FHR).

d Natural vaginal delivery.

e Cesarean section.

f CB was not observed in Patient 5 in sonography three weeks later with the gestation age of 9 weeks.

g A second experience of nonviable pregnancy outcome, three month after our study, occurred with similar result of abortion in 8th week.

As 5 out of 8 patients were not diagnosed with fetal embryo at the time of the study so the gestational age was recorded on MSD instead CRL.

It should be noted that in normal pregnancies the embryo is definitely identifiable by TVS when the MSD is 16–18 mm or more [10] but patient 7 with MSD of 20 mm showed no fetal embryo.

Overall, of 8 pregnant women, 5 showed live birth (62.5%) and 3 experienced fetal demise (37.5%). The cho-rionic bumps ranged in size (maximum dimension) from 0.1 cc to 1.8 cc (average, 0.73 cc). The average age of pregnant mothers was 32 years (23–41 years) and the average gestational age was 7 weeks 0 (range, 5 weeks 4 days–8 weeks 5 days).

Despite the request for subsequent sonography, only 2 patients referred to our center for this purpose (Patient 5 and 6 in Table 1). CB was not observed in Patient 5 in so-nography three weeks later with the gestation age of 9 weeks. In Patient 6, sonography one week later showed that CB size increased from 0.3 to 0.8 ml but the pregnancy outcome was normal ending up in live birth. The other three patients from those diagnosed with CB, were contacted by telephone concerning pregnancy outcome, who reported a decreased CB size. Of the three patients with a nonviable outcome, two patients reported previous nonviable pregnancy outcome, and the third patient who was contacted by telephone reported a previous CB-related nonviable pregnancy outcome and a second experience of nonviable pregnancy outcome following a subsequent pregnancy. The last patient showed vaginal bleeding on sonography which was possibly due to taking misoprostol. As the patient reported, her physician recommended abortion due to the intake of anti-hepatitis medication and teratogenic effect of that drug. The question which arises is whether the patient who took misoprostol and was diagnosed with CB would end up experiencing nonviable pregnancy outcome without misoprostol. The first patient (number 1) reported 3 previous nonviable pregnancy outcomes due to high bicornuate uterus and the last patient (number 8) suffered nonviable pregnancy outcome due to trauma. One patient (number 3) reported the history of molar pregnancy with live birth outcome. Two patients had hypothyroidy one of whom (number 1) had nonviable fetus and the other (number 4) experienced live birth. All 5 fetuses were delivered full-term (3 Cesarean and 2 Natural vaginal delivery). None of them had a history of smoking, coagulopathy, infertility, multiple gestation. No significant relationship was found between these factors and the size of CB. All 8 patients had single CB. Figures 1–4 represent some examples. In our study, unlike Sana, the relationship between CB and umbilical cold was not considered. One patient (number 5) suffered subchorionic hemorrhage with a live birth outcome. “Sonography lacked vascularity on color or power Doppler imaging; a bump with peripheral and central hyper echogenicity with a low level echo as well as choriodecidual irregularity, focal bulging toward the center and surface irregularity was observed inside the sac” [1].

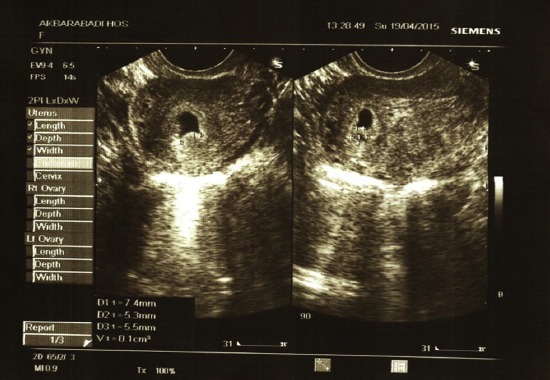

Figure 1.

Transvaginal image of a chorionic bump; age of gestation: 7 weeks, 1 day, gravid 1, para 0, which resulted in a normal pregnancy outcome in a 35-year-old woman. The bump measured 0.9 cc. The pregnancy resulted in live birth in Week 37.

Figure 4.

Transvaginal image of a chorionic bump; age of gestation: 6 weeks, gravid 3, para1 Ab1, which resulted in a normal pregnancy outcome in a 23-year-old woman. The bump measured 0.1 cc. MSD = 11 mm. The pregnancy resulted in live birth in Week 37.

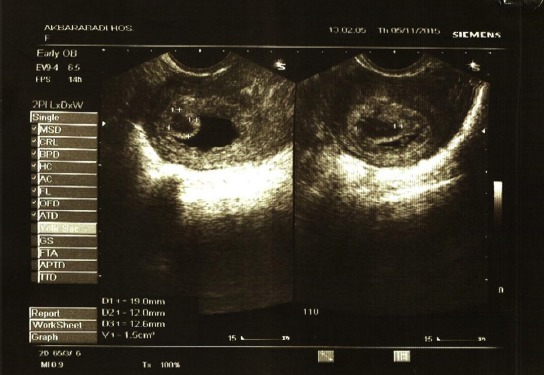

Figure 2.

Transvaginal image of a chorionic bump; age of gestation: 5 weeks, 4 days, gravid 4, para2 Ab1, which resulted in a normal pregnancy outcome in a 33-year-old woman. The bump measured 0.6 cc. MSD = 9.5 mm. The pregnancy was full term.

Figure 3.

Transvaginal image of a chorionic bump; age of gestation: 8 weeks, 5 days, gravid 1, para 0, which resulted in a normal pregnancy outcome in a 30-year-old woman. The bump measured 1.5 cc. MSD = 29 mm. The pregnancy resulted in fetal demise in Week 9.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the live birth rate of pregnancies with a diagnosis of a chorionic bump on firsttrimester sonography, and to give radiologists and gynecologists an insight into CB and its importance. The main finding was that the frequency of live birth in our sample was 62.5% (5 from 8) which is consistent with Arleo et al. who reported a livebirth rate of 62% (N = 119)and Sana etal. who observeda live birth rate of 65% (N = 57). Harris et al. reported a live birth rate of less than 50% (n = 15) [1]. This low rate has been attributed to a small sample size, but interestingly the live birth rate in our study is consistent with the live birth rate reported in recent studies. Incidence rate in the present study was found to be 0.4% which is less than that reported by Harris et al., i.e., 0.7% and Sana et al., i.e., 1.5–7 per 1000 individuals, and Arleo et al., i.e., 5–7 per 1000 individuals, which can be ascribed to the small sample size in our study. The incidence of chorionic bump was reported 23 per 1000 by Joseph et al. was prominently higherthan Sana et al. This can be explained by the fact that chorionic bump is more common among pregnant women who are subject to a higher risk for fetal aneuploidy compared to general obstetric population. Their study found that chorionic bump obviously increased the likelihood of chromosomal abnormality in high riskfetuses [9]. Results of fourpreviousstudiesare presented in Table 2 for comparison with our study.

Table 2.

Summary of 5 articles on CB.

| Our study | Harris et al. | Sana et al. | Arleo et al. | Joseph et al. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study period | 2014−2016 | 2001−2004 | 203−2010 | 2004−2007 | 2010−2015 |

| Number of patients | 1900 | 2178 | 37,798 | 7280−10,400 | 690 |

| Prevalance | 4 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 | 1.5−7 per 1000 | 5−7 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 |

| Live birth rate % | 62.5 | <50 | 62 | 65 | Not mentioned |

The main reason for the small sample size in the present study is the shorter time period compared to the time frame considered by Sana et al. and Arleo et al., and Harris et al. Secondly, Akbarabadi Hospital is a major referral center for women in Tehran and a large number of first trimester so-nographies are performed by a university lecturer in the morning and residents in the afternoon and evening.

However, due to the recent introduction of CB, and the possibility of failure to diagnose CB or mistaking it with subchorionic hemorrhage only the sonographies performed by the university lecturer were included in the data and those performed by residents were excluded. According to Harris et al. subchorionic hemorrhage appears to be venous mostly conforming to the gestational sac shape while CB tends to be more arterial, depicting hypoecho centeric or oval bleeding on the outer side of the choriodecidual reaction. It also develops intervillous space or chorionic plate, and bulges into the gestational sac [1].Considering MRI findings, CB showed T1 hypersignal intensity and hemorrhage between villus formation and a decidual in pathologic evaluation [2].

Also, in sonography avascular was observed with a low-level echo [1]. All the above findings can contribute to differentiation of CB and subchorionic hemorrhage. Unfortunately, except for two patients, sonographies were not examined to detect changes over time in the size of CB which is a limitation of the present study. However, the cases in our study showed a decreased size of CB observed in sonography examination performed by other centers. Arleo et al. reported that 91% of live births in their study showed absorption chorionic bump by 12 weeks suggesting the possibility that the CB can reabsorb the underlying process [2]. Vaginal bleeding was not observed in the 7 patients in our study and the only case who showed vaginal bleeding had a history of misoprostol which might be the possible cause of bleeding. Other studies have not observed a significant communication between vaginal bleeding, CB, and pregnancy outcome the same as ours. Arleo et al. noted the importance of the number of CBs rather than its size [2]. The cases in our study had no more than a single CB and we believe that the correlation between bump size and pregnancy outcome is not clear. Harris and Arleo observed no significant correlation between coagulopathy and pregnancy outcome [1,2]. None of the 5 cases in our study reported clear abnormality in the newborn or in the second trimester screening sonography based on the verbal reports by the patient. In a case report by Wegrzyn et al., CB was observed along with acrania which, due to its rarity, might be accidental and attributable to deficiency of acid folic or an extraneous factor. Whether there is a correlation between folate deficiency and CB is yet unclear and needs to be studied by future research [5]. A systematic study by Ammon et al. reported the rate of nonviable pregnancy outcome in week 5–20 to be 11 to 22 percent which obviously decreases by 2–4 percent after the development of the heart [11].Thus, even considering the first percentage above, i.e., 11 –22, the rate of nonviable pregnancy outcome in our study, i.e., 37.5 percent and the rate reported in the study conducted by Arleo (i.e., 18 percent) [2] show that CB is a major nonviability risk factor. Given that in our study, two patients had prior experience of nonviable pregnancy and one patient suffered a second nonviable pregnancy, the question which raises here is whether CB is causal to the poor outcome of their current pregnancy or whether poor pregnancy outcome would ensue even without the presence of CB especially with regard to their prior experience of nonviable pregnancy outcome given to Joseph et al. A sonographically non-isolated chorionic bump is not indicative of considerable additional aneuploidy risk, whereas a sonographically isolated chorionic bump significantly increased the possibility of aneuploidy in high-risk fetuses [9] but in the current study we did not conduct a genetic test on nonviable patients. Only, patient 1 and 2 aged 40 and 41 years with demise outcome and previous history of abortion underwent the genetic test with normal results. As mentioned above, Harris et al. and Arleo et al. did not observe a correlation between coagulopathy and live birth outcome [1,2]. However, the possible relationship between CB and maternal factor such as uterine abnormality and systemic disease reasons is still obscure, which should be considered by future research.

However, considering the low incidence in both patients and the literature of CB, further studies on chorionic bumps and the risk of demise would be helpful for full delineation of this infrequent first-trimester sonographic finding.

Acknowledgement

We thanks Iran University of Medical Science and Akbar-abadi Hospital for providing us with data and facilities to conduct this study.

Footnotes

Authorship & conflicts of interest: The two authors have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors. To the best of our knowledge, no conflict of interest, financial or other, exists.

References

- [1].Harris RD, Couto C, Karpovsky C, et al. The chorionic bump: a first-trimester pregnancy sonographic finding associated with a guarded prognosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:757. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Arleo EK, Troiano RN. Chorionic bump on first-trimester so-nography: not necessarily a poor prognostic indicator for pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;343:137. doi: 10.7863/ultra.34.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Arleo EK, Dunning A, Troiano RN. Chorionic bump in pregnant patients and associated live birth raten;a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34(4):553–7. doi: 10.7863/ultra.34.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sana Y, Appiah A, Davison A, et al. Clinical significance of firsttrimester chorionic bumps: a matched case-control study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:585. doi: 10.1002/uog.12528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wegrzyn P, Brawura-Biskupski-Samaha R, Borowski D, et al. The chorionic bump associated with acrania-case report. Ginekol Pol. 2013;84(12):1055–8. doi: 10.17772/gp/1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Stampone C, Nicotra M, Muttinelli C, et al. Transvaginal so-nography of the yolk sac in normal and abnormal pregnancy. J Clin Ultrasound. 1996;24:3–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0096(199601)24:1<3::AID-JCU1>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Makikallio K, Tekay A, Jouppila P. Yolk sac and umbil-icoplacental hemodynamics during early human embryonic development. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;14:175–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.14030175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ahmed MH, Raman V, Musa S. Chorionic bump: off the beaten path, first trimester sonographic finding [Google Scholar]

- [9].Joseph R, Angelina C, Christian L, et al. First-trimester cho-rionic bump-association with fetal aneuploidy in a high- risk population. J Clin Ultrasound. 2017;45:3–7. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rumak CM. Diagnostic ultrasound. 4th ed. Philadelphia: PA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ammon Avalos L, Galindo C, Li DK. A systematic review to calculate background miscarriage rates using life table analysis. Birth Defects Res Part A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94(6):417–23. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]