Abstract

Background

The aim of the study was to investigate the role of von Willebrand factor (vWF), the vWF-cleaving protease, ADAMTS13, the composition of thrombus, and patient outcome following mechanical cerebral artery thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Material/Methods

A prospective cohort study included 131 patients with ischemic stroke (<6 hours) with or without intravenous thrombolysis. Interventional procedure parameters, hemocoagulation markers, vWF, ADAMTS13, and histological examination of the extracted thrombi were performed. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was used on hospital admission, after 24 hours, at day 7; the three-month modified Rankin Scale score was used.

Results

Mechanical thrombectomy resulted in a Treatment in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score of 2–3, with recanalization in 89% of patients. Intravenous thrombolysis was used in 101 (78%). Patients with and without intravenous thrombolysis therapy had a good clinical outcome (score 0–2) in 47% of cases (P=0.459) using the three-month modified Rankin Scale. Patients with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score ≥15 had significantly increased vWF levels (P=0.003), and a significantly increased vWF: ADAMTS13 ratio (P=0.038) on hospital admission. Significant correlation coefficients were found for plasma vWF and thrombo-embolus vWF (r=0.32), platelet (r=0.24), and fibrin (r=0.26) levels. In the removed thrombus, vWF levels were significantly correlated with platelet count (r=0.53), CD31-positive cells (r=0.38), and fibrin (r=0.48).

Conclusions

In patients with acute ischemic stroke, mechanical cerebral artery thrombectomy resulted in a good clinical outcome in 47% of cases, with and without intravenous thrombolysis therapy.

MeSH Keywords: Fibrinolysis, Intracranial Thrombosis, Stroke, Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, Thrombectomy, von Willebrand Factor

Background

Mechanical thrombectomy of the cerebral arteries is a method used for acute ischemic stroke therapy, with technical success rates of between 80–90% reported for large vessel occlusion recanalization following failed intravenous thrombolysis [1–8]. The most frequently used methods for mechanical intracranial thrombus extraction in large vessel occlusion include a direct aspiration first pass technique (ADAPT), stent retrievers, the Penumbra system for mechanical thrombectomy by aspiration, a direct aspiration first pass technique, or thrombo-aspiration using the Solumbra procedure [1–8]. A meta-analysis of mechanical thrombectomy clinical trials showed that the probability of recovery is twice as high in patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy compared with that in patients treated with systemic thrombolysis alone [9]. However, several other meta-analysis reports have shown that mechanical thrombectomy fails clinically in between 30–40% of treated patients [10–13]. From a clinical point of view, it is essential to determine the significant clinical, hematological, and immunological, predictors of mechanical thrombectomy success or failure, as well as the constituents of the removed thrombus, and to evaluate the clinical outcome at three months following treatment [14–16]. In some patients, achieving vessel recanalization may not be possible, and in other patients, extensive cerebral infarction can occur, despite successful mechanical recanalization.

Patients with heart rhythm disturbances that result in cerebral thrombo-embolism have been reported, in between 50–60% of cases, with prothrombotic changes and abnormalities in hemostasis, and arrhythmias lead to thrombus formation and thromboembolic occlusion of the cerebral arteries [17,18]. An impaired prognosis is associated with increased thrombus adhesion to the vessel wall and with increased levels of von Willebrand factor (vWF) and there is also a pro-thrombotic effect of the local vascular inflammatory response to a recent and occlusive embolic thrombus [19–21].

It has been shown that vWF plays a major role in platelet adhesion to damaged endothelium and directly binds extracellular DNA released from leukocytes, mediating leukocyte binding to endothelial cells, resulting in increased vascular permeability [22,23]. Large-sized vWF multimers released from damaged endothelium are cleaved into smaller, less-coagulant forms, by the metalloprotease, ADAMTS13 [24–26]. With decreased ADAMTS13 activity, these large vWF multimers may not be sufficiently lyzed, which can alter the effects of vWF in thrombus formation, adhesion of thromboembolus to the cerebral artery endothelial cells, leukocyte recruitment, and vascular permeability around an occlusive thromboembolus [24–26].

This study design aimed to determine the significance of elevated vWF, and reduced ADAMTS13 activity, in the clinical outcome of patients with acute stroke, using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Score (NIHSS) on hospital admission, length of the embolus extraction procedure, Treatment in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score for recanalization, and the three-month modified Rankin Scale and thrombus composition [27,28]. This study also was designed to investigate the potential role of the inflammatory response to thromboembolism in the acute and later stages of ischemic stroke [16,29,30]. Therefore the study included the histological examination of the extracted thromboemboli, as well as the levels of vWF (and the activity of ADAMTS13 [15,31,32].

The aim of the study was to determine the role of von Willebrand factor (vWF), and the von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease, ADAMTS13, and the composition of thrombus and patient outcome following mechanical cerebral artery thrombectomy in patients with ischemic stroke treated with and without intravenous thrombolysis.

Material and Methods

Study design

The design of this study was approved by the local ethical committee (Ref: 639/2017). All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study. A prospective cohort study included 131 consecutive patients with acute ischemic stroke, having occurred within <6 hours, with or without the use of intravenous thrombolysis using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) (Actilyse, Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany). Following a mechanical thrombectomy procedure all patients included in the study had confirmed large vessel thromboembolic occlusion, and their neurological clinical status was assessed with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) obtained on hospital admission, after 24 hours, at day 7, and finally, at three months, using the three-month modified Rankin Scale.

Time indicators of acute ischemic stroke and hospital admission included onset-to-door (OTD), door-to-needle (DTN), onset-to-needle (OTN), and onset-to-recanalization (OTR) were evaluated. Early ischemic changes and collateral circulation were assessed by the Alberta Stroke Program for Early CT Score (ASPECTS). Computed tomography angiography (CTA), or digital subtraction angiography (DSA), was used for localization of large cerebral vessel occlusion and measurement of thrombus length.

Neuro-interventional procedure data was obtained by using the Treatment in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score, number of mechanical attempts, type of procedure, and procedure duration. The thromboemboli extracted using mechanical thrombectomy were immediately placed into a transport vial containing the fixative, 10% formalin, and transferred to the laboratory for processing for light microscopy and immunohistochemistry. At the same time, 40 ml of peripheral blood was collected from each patient to examine blood levels of on Willebrand factor (vWF), the von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease, ADAMTS13, and other coagulation factors and inflammatory mediators, using routine clinical laboratory standards and techniques, prior to initiation of the mechanical interventional procedure and later on day 5±2 days from the onset of the acute ischemic stroke.

Study population

A total of 131 patients, 69 men (53%) and 62 women (47%), with a median of age 71 years (IDR, 53–82 years) underwent mechanical thrombectomy for cerebral large vessel occlusion. Intravenous thrombolysis therapy was used in 101 (78%) patients, which failed to result in vessel recanalization. The Alberta Stroke Program for Early CT Score (ASPECTS) findings were in the IDR of 6–10 points in 129 patients (99%), and the ASPECTS scoring IDR was 3–5 points in 69% of patients, with collateral circulation, analyzed from the initial CTA imaging findings. Time parameters were obtained for all patients; the median of the time from the stroke onset to the mechanical thrombectomy procedure was 160 minutes (IDR: 100–270 min), and the median of procedure duration was 45 minutes (IDR: 25–85 min). Demographic variables, risk factors, and procedure description variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and medical history.

| Variable | Categories | n (%) | OR (95% CI)* | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 62 (47) | 0.95 (0.44–2.05) | 0.999 |

| Male | 69 (53) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | No | 99 (79) | 2.62 (0.98–6.98) | 0.064 |

| Yes | 27 (21) | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | No | 55 (44) | 0.58 (0.27–1.27) | 0.237 |

| Yes | 71 (56) | |||

| Hypertension | No | 27 (21) | 3.33 (1.17–9.52) | 0.026 |

| Yes | 99 (79) | |||

| Smoking | No | 101 (80) | 1.18 (0.46–2.99) | 0.815 |

| Yes | 25 (20) | |||

| Alcohol abuse | No | 124 (98) | NA | NA |

| Yes | 2 (2) | |||

| Arrhythmia | No | 75 (60) | 1.09 (0.50–2.37) | 0.846 |

| Yes | 51 (40) | |||

| Previous TIA | No | 121 (96) | 0.87 (0.12–6.42) | 0.999 |

| Yes | 5 (4) | |||

| Previous stroke | No | 106 (84) | 1.95 (0.67–5.68) | 0.300 |

| Yes | 20 (16) | |||

| Variable | Units | Median (IDR) | P** | |

| Age | Years | 71 (53–82) | <0.001 | |

| Systolic BP | mmHg | 151 (120–184) | 0.100 | |

| Diastolic BP | mmHg | 85 (70–107) | 0.471 | |

| Glycemia | mmol/l | 6.8 (5.3–9.2) | 0.832 | |

| Cholesterol | mmol/l | 4.4 (3.4–6.1) | 0.469 | |

| BMI | kg/cm2 | 27.7 (22.9–35.2) | 0.187 | |

| Inception to IVT | min | 92 (62–152) | 0.022 | |

| Inception to DSA | min | 160 (100–270) | 0.561 | |

| Arrival to IVT | min | 25 (17–40) | 0.140 | |

| Arrival to DSA | min | 58 (20–90) | 0.493 | |

| Procedure duration | min | 45 (25–85) | 0.139 | |

| Recanalization | min | 200 (130–330) | 0.432 | |

Odds ratios for achieving better clinical status were computed (where possible), together with 95% confidence intervals and p-values of Chi-square test of independence (or Fisher’s exact test where necessary);

P-values of Mann-Whitney U test were computed to compare patients with three-month modified Rankin Scale (3M-mRS) score of 0–2 and patients with a three-month modified Rankin Scale score of 3–6.

Intravenous thrombolysis (IVT); digital subtraction angiography (DSA).

Mechanical interventions

Mechanical thrombectomy with a stent retriever, Penumbra aspiration device, or combination techniques was performed in the University Hospital Ostrava, Interventional Neuroradiology and Angiology Department, Czech Republic. A GE-Innova IGS 630 biplane system (GE Healthcare, Buc, France) was used for brain and vascular imaging of mechanical intervention and post-procedure three-dimensional (3D) X-ray angiography reconstruction.

Large vessel occlusions were recanalized with a pRESET thrombectomy device (Phenox GmbH, Bochum, Germany), Catch retriever (Balt Extrusion, Montmorency, France), Solitaire stent retriever (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland), or Penumbra aspiration system (Penumbra, Inc., Alameda, CA, USA). Cerebral vessels were accessed using a Flexor 6-7 F/90 cm guiding sheath (Cook Medical, Bjaeverskov, Denmark) or Terumo Destination guiding catheter (Terumo Medical Corp., Elkton, MD, USA). Large vessel occlusions were traversed with the Prowler Select Plus microcatheter (Codman & Shurtleff Inc., Raynham, MA, USA) over several types of 0.014” microwires. For the thrombus aspiration technique, ACE64 and 3MAX Penumbra catheters were used with the original suction pump. The type of anesthesia was recorded during the procedure, intravenous analgosedation with a laryngeal mask, or general anesthesia.

Analysis of hemostasis

Blood samples were collected from all patients before commencing the mechanical endovascular procedure and before the use of intra-arterial administration of heparin. Blood samples were analyzed for complete blood count (CBC) and reticulocytes using a Sysmex XN 9000 (Sysmex Corporation, Norderstedt, Germany). The coagulation tests, prothrombin time (PTT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), thrombin time (TT), fibrinogen, and Factor VIII (FVIII), were measured on a fully automated blood analyzer (Siemens CS-5100) with Dade Innovin for PT, Pathromtin SL for APTT, Thromboclotin for TT, Dade Thrombin Reagent for fibrinogen, and Coagulation Factor VIII Deficient Plasma for FVIII. Immunoassay methods for D-dimers and vWF were conducted using Innovance D-dimers and Siemens vWF/Ag (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Erlangen, Germany). ADAMTS13 activity was determined in citrated double-spun, platelet-poor plasma using the commercial Technozym® ADAMTS13 chromogenic enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method (Technoclone, Vienna, Austria), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Blood and serum analysis

The following parameters were determined prior to the mechanical interventional procedure and 5±2 days after the procedure. White blood cell (WBC) count and a differential were performed on the Sysmex XN2000 analyzer with Sysmex diagnostics. Lymphocyte subpopulations in peripheral blood were analyzed using a Navios flow cytometer and Beckman-Coulter diagnostic antibody cocktail Tetrachrome 45/56/19/3 (Ref: 66070703), CD8 PC7 (Ref: 737661), CD4-Alexa Fluor 750 (Ref: A94682), CD16-RPE (Ref: A07766), CD3-FITC/anti-HLA-DR-PE (Ref: A07737), CD45-PC5 (Ref: A07785), and anti-HLA-DR-PC7 (Ref: B49180). Serum calprotectin concentrations were determined using a CalproLab ELISA kit (Calpro AS).

Histopathology

Thrombus material obtained during mechanical thrombus extraction was fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin. Formalin-fixed specimens were embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned at 4 μm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Primary antibodies against vWF and CD31 were used to identify neutrophils and monocytes; anti-CD15 was used to identify neutrophils, eosinophils, and some monocytes; and Carstairs’ histochemical method was used to identify platelets and fibrin.

Histological examination was performed without knowledge of the clinical findings and was based on detection analysis of vWF, platelet and fibrin accumulation, as well as neutrophil and monocyte deposits and erythrocyte-rich areas. The percentages of platelets, vWF-stained areas, fibrin, and CD31-positive cells were quantitatively determined. Histological sections were photographed with an Olympus BX41 microscope with an attached QuickPHOTO CAMERA (PROMICRA, Prague, Czech Republic). The positive immunostained results were quantified digitally using scanning digital photomicroscopy and processing with QuickPHOTO CAMERA software as a percentage of the total area of the digital image. Objective images were evaluated at ×4 and ×10 objective magnification for the measurement of positively immunostained stained areas in square centimeters, with the average of five measurements from different sample areas within the sections.

Statistical analysis

For univariate description of variables, the median and the interdecile range (IDR) was used, because of the occurrence of several outliers that could have affected the analysis. For graphical representation, boxplots were used, which were useful for exploring the structure of selected variables and effective graphical comparison of several groups of interest. Depending on the nature of the data, the Mann-Whitney U test, paired sign test, or Kruskal-Wallis test were used to evaluate statistically significant differences between groups.

The assessment of relationships between two variables used computation of the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, with correlograms used to display better the relationships evaluated (significance level 0.05). The odds ratio (OR), a widely used measure of the association between the presence of a risk factor and outcome, was used and the Chi-square test of independence or Fisher’s exact test were used, where relevant.

Results

Study population

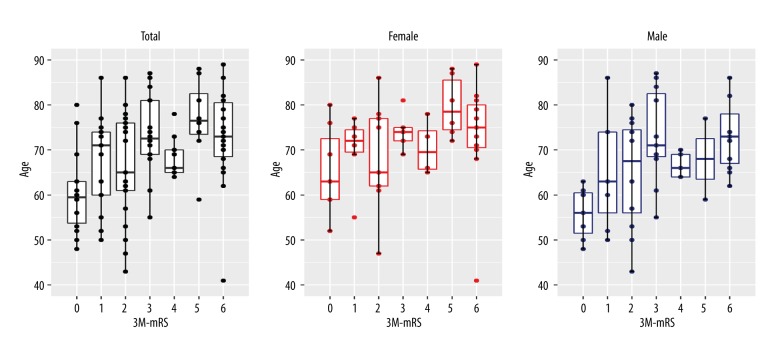

Of the 131 patients included in the study, men and women did not differ in terms of age distribution (P=0.239), or three-month modified Rankin Scale score (P=0.706), but younger patients fared better on the three-month modified Rankin Scale score (P=0.007) (Figure 1). The right hemisphere was involved in acute ischemic stroke in 49 patients, the left hemisphere in 63 patients, and the posterior cerebral circulation was involved in 17 patients. Hypertension was clinically diagnosed in 99 patients (79%), and patients without hypertension had significantly increased odds of achieving a better clinical outcome (OR 3.33; 95% CI, 1.17–9.52; P=0.026) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Age comparison of clinical outcome. Age by three-month modified Rankin Scale score Multiple boxplots show whether patients with better three-month modified Rankin Scale score (3M-mRS) were younger or older than patients with worse three-month modified Rankin Scale score. There was a significant difference in terms of the age of all patients with reference to the three-month modified Rankin Scale score (P=0.007).

Mechanical thrombectomy

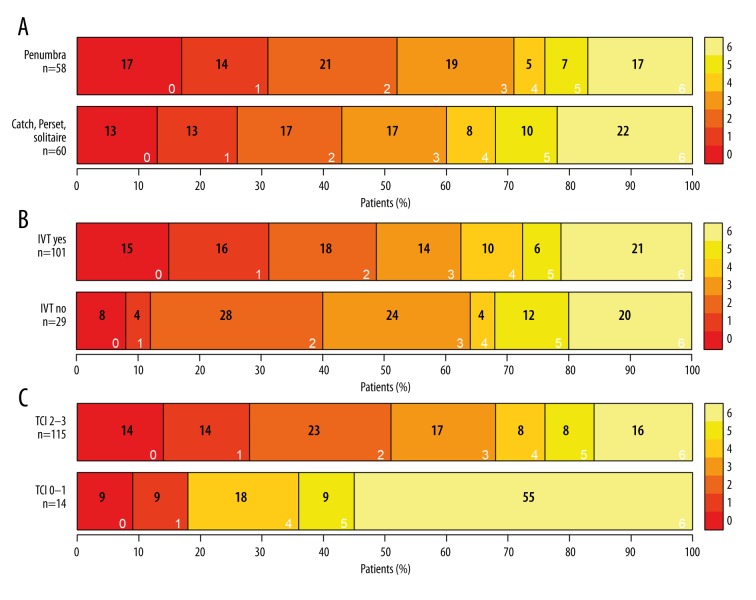

A mechanical thrombectomy procedure was carried out in acute ischemic stroke patients with large vessel occlusion, with or without previous intravenous thrombolysis before hospital admission. The selected time parameters after stroke inception to interventional procedures were reported in minutes (Table 1). The three-month modified Rankin Scale scores did not differ with different mechanical thromboembolism extraction devices (stent retrievers or aspiration devices) (P=0.98) (Figure 2A). Intravenous thrombolysis was used prior to the mechanical interventional procedure in 101 (78%) patients, and intravenous thrombolysis was not used in 29 (22%) patients; these groups did not differ in terms of the three-month modified Rankin Scale scores for clinical outcome (P=0.459) (Figure 2B). Treatment resulted in a Treatment in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score of 2–3 for recanalization in 115 (89%) of patients, while a TICI score of 0–1 was found in 14 (11%) patients, and these groups differed significantly in terms of the three-month modified Rankin Scale scores (P=0.027) (Figure 2C) (Table 2). Patient overall mortality rate was 21% (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Patient outcome following mechanical thrombectomy. (A) Extraction devices and three-month modified Rankin Scale (3M-mRS) score: three months after the procedure, no significant difference was observed between the extraction devices used (P=0.98). (B) Intravenous thrombolysis: no significant difference in the three-month modified Rankin Scale score (P=0.459) between the groups of patients with and without intravenous thrombolysis before the interventional procedure. (C) Treatment in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score for recanalization: significantly better clinical outcomes (P=0.027) were observed in patients with TICI score of 2–3 for recanalization of the large vessel occlusion (LVO) than in patients with a TICI score of 0–1 for recanalization.

Table 2.

Thrombectomy procedure and clinical outcome.

| Procedure description | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Categories | n (%) | OR (95% CI)* | P* |

| Intravenous thrombolysis (IIVT) | No | 29 (22) | 0.70 (0.28–1.75) | 0.497 |

| Yes | 101 (78) | |||

| Alberta Stroke Program for Early CT Score (ASPECTS) | 0–5 | 1 (1) | NA | NA |

| 6–10 | 129 (99) | |||

| Alberta collateral scoring | 0–2 | 40 (31) | 0.17 (0.06–0.46) | <0.001 |

| 3–5 | 89 (69) | |||

| SICH | No | 122 (97) | NA | NA |

| Yes | 4 (3) | |||

| Non-SICH | No | 103 (82) | 1.81 (0.66–4.99) | 0.321 |

| Yes | 23 (18) | |||

| Decompression | No | 125 (99) | NA | NA |

| Yes | 1 (1) | |||

| Type of used anesthesia | Local anesthesia | 10 (7) | ||

| IV sedation | 69 (51) | 0.70 (0.32–1.57) | 0.388 | |

| General anesthesia | 52 (39) | |||

| Previous statin medication | No | 50 (40) | 0.53 (0.24–1.17) | 0.166 |

| Yes | 76 (60) | |||

| Previous antithrombotic medication | No | 57 (45) | 2.39 (1.09–5.26) | 0.032 |

| Yes | 69 (55) | |||

| Clinical outcome | ||||

| Variable | Categories | n (%) | ||

| The thrombolysis in cerebral infarction grading system | (0) – no perfusion | 8 (6) | ||

| Treatment in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score | (1) – minimal perfusion | 6 (5) | ||

| (2) – partial perfusion | 36 (28) | |||

| (3) – complete perfusion | 79 (61) | |||

| NIH Stroke Scale at the time of arrival to the hospital (NIHSS-entry) | Minor | 2 (2) | ||

| Moderate | 41 (33) | |||

| Moderate to severe | 53 (42) | |||

| Severe | 30 (23) | |||

| NIH Stroke Scale 24 hours after the mechanical thrombectomy procedure (NIHSS-24 h) | Minor | 28 (23) | ||

| Moderate | 66 (54) | |||

| Moderate to severe | 18 (15) | |||

| Severe | 11 (8) | |||

| NIH Stroke Scale 7 days after the mechanical thrombectomy procedure (NIHSS-7 d) | Minor | 43 (36) | ||

| Moderate | 57 (48) | |||

| Moderate to severe | 12 (10) | |||

| Severe | 7 (6) | |||

| Modified Rankin Scale 3 months after the mechanical thrombectomy procedure (three-month modified Rankin Scale) | 0–2 | 49 (47) | ||

| 3 | 17 (16) | |||

| 4–5 | 17 (16) | |||

| 6 | 22 (21) | |||

Odds ratios for achieving better clinical status were computed (where possible), together with 95% confidence intervals and p-values of Chi-square test of independence (or Fisher’s exact test where necessary).

Blood coagulation

Hemocoagulation and the associated inflammation response analysis data are shown in Tables 3–6. Patients with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score >15 had significantly increased levels of vWF antigen (%) (P=0.003) on hospital admission for acute stroke therapy (median: 216; IDR: 137–374); patients with an NIHSS ≤15 had significantly lower vWF levels (median: 175; IDR: 132–276). Also, patients with lower three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 3–6 had significantly increased levels of vWF (P<0.001) (median: 225; IDR: 160–379) compared with vWF levels in patients with three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 0–2 (median: 174; IDR: 118–298) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Hemocoagulation response and entry National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

| Variables | Status before the procedure | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIHSS ≤15 | NIHSS >15 | ||

| PLT (Platelet) | 196 (124; 313) | 201 (151; 272) | 0.948 |

| PTC (Plateletcrit) | 0.2 (0.2; 0.3) | 0.2 (0.2; 0.3) | 0.359 |

| MPV (Mean Platelet Volume) | 11.7 (10.0; 13.0) | 11.2 (10.2; 12.6) | 0.309 |

| PDW (Platelet Distribution Width) | 14.1 (11.3; 17.8) | 13.8 (11.6; 17.2) | 0.731 |

| IPF (Immature Platelet Fraction) | 3.3 (1.7; 7.7) | 3.7 (1.6; 8.4) | 0.862 |

| P-LCR (Platelet Large Cell Ratio) | 38.8 (24.1; 47.2) | 34.0 (25.5; 46.0) | 0.321 |

| WBC (White Blood Cells) | 10.0 (6.4; 12.5) | 9.1 (6.1; 14.7) | 0.531 |

| Mono (Monocytes) | 0.6 (0.3; 1.1) | 0.6 (0.4; 0.9) | 0.708 |

| Hgb (Hemoglobin) | 128 (109; 151) | 133 (107; 149) | 0.545 |

| HTC (Hematocrit) | 0.383 (0.322; 0.443) | 0.390 (0.326; 0.450) | 0.397 |

| PT-R (Prothrombin Time-Ratio) | 1.1 (1.0; 1.3) | 1.1 (1.0; 1.3) | 0.981 |

| APTT-R (Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time-Ratio) | 1.0 (0.8; 3.2) | 0.9 (0.8; 1.9) | 0.222 |

| TT (Thrombin Time) | 18 (14; 30) | 18 (14; 30) | 0.974 |

| Fbg (Fibrinogen) | 2.42 (1.44; 3.47) | 2.37 (1.28; 3.70) | 0.651 |

| D-dimers | 3.3 (0.7; 15.1) | 3.4 (0.8; 24.8) | 0.596 |

| vWF (von Willebrand Factor) | 175 (132; 276) | 216 (137; 374) | 0.003 |

| FVIII (Factor VIII) | 174 (73; 280) | 177 (70; 363) | 0.397 |

| ADAMTS13 | 74 (21; 100) | 71 (16; 98) | 0.601 |

| vWF: ADAMTS13 ratio | 2.5 (1.5; 7.9) | 3.0 (1.9; 15.9) | 0.038 |

| CRP (C-Reactive Protein) | 4.1 (1.0; 13.8) | 5.2 (1.1; 31.6) | 0.122 |

P-values of Mann-Whitney U test were computed to compare patients with different outcomes.

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

Table 4.

Hemocoagulation response and three-month modified Rankin Scale.

| Variables | Outcome after 3 months | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRS 0–2 (n=49) | mRS 3–6 (n=56) | ||

| PLT (Platelet) | 195 (147; 284) | 205 (148; 271) | 0.584 |

| PTC (Plateletcrit) | 0.24 (0.19; 0.33) | 0.23 (0.17; 0.31) | 0.987 |

| MPV (Mean Platelet Volume) | 11.6 (10.2; 12.7) | 11.2 (10.2; 12.8) | 0.529 |

| PDW (Platelet Distribution Width) | 14.1 (11.8; 17.6) | 13.8 (11.6; 17.6) | 0.497 |

| IPF (Immature Platelet Fraction) | 3.8 (1.6; 9.0) | 3.5 (1.8; 7.8) | 0.590 |

| P-LCR (Platelet Large Cell Ratio) | 37.4 (26.1; 46.4) | 34.0 (26.2; 47.1) | 0.493 |

| WBC (White Blood Cells) | 9.7 (6.1; 13.3) | 8.6 (6.1; 16.1) | 0.322 |

| Mono (Monocytes) | 0.6 (0.4; 1.2) | 0.6 (0.4; 1.0) | 0.333 |

| Hgb (Hemoglobin) | 130 (112; 152) | 130 (104; 152) | 0.489 |

| HTC (Hematocrit) | 0.386 (0.326; 0.446) | 0.390 (0.323; 0.452) | 0.987 |

| PT-R (Prothrombin Time-Ratio) | 1.07 (0.98; 1.36) | 1.10 (1.00; 1.38) | 0.430 |

| APTT-R (Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time-Ratio) | 1.0 (0.8; 3.1) | 1.0 (0.8; 2.1) | 0.365 |

| TT (Thrombin Time) | 18 (14; 32) | 19 (14; 30) | 0.912 |

| Fbg (Fibrinogen) | 2.4 (1.3; 3.5) | 2.2 (1.2; 3.8) | 0.566 |

| D-dimers | 2.6 (0.7; 10.7) | 4.4 (0.8; 26.0) | 0.029 |

| vWF (von Willebrand Factor) | 174 (118; 298) | 225 (160; 379) | <0.001 |

| FVIII (Factor VIII) | 150 (50; 320) | 190 (70; 340) | 0.267 |

| ADAMTS13 | 66 (15; 93) | 78 (20; 101) | 0.047 |

| vWF: ADAMTS13 ratio | 3.1 (1.6; 15.4) | 3.0 (1.7; 15.4) | 0.689 |

| CRP (C-Reactive Protein) | 4 (1; 24) | 5 (2; 31) | 0.078 |

P-values of Mann-Whitney U test were computed to compare patients with different outcomes.

Table 5.

Inflammatory response and clinical outcome.

| Inflammatory response 3–7 days after stroke | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Outcome 7 days after stroke | P* | |

| NIHSS ≤15 | NIHSS >15 | ||

| WBC | 8.5 (6.0–12.7) | 11.6 (6.6–14.9) | 0.019 |

| Neutrophils | 5.7 (3.8–9.0) | 9.1 (4.6–11.0) | 0.002 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.67 (1.02–2.34) | 1.19 (0.90–2.08) | 0.052 |

| Monocytes | 0.82 (0.52–1.25) | 0.88 (0.53–1.26) | 0.622 |

| Eosinophils | 0.20 (0.04–0.42) | 0.13 (0.02–0.31) | 0.136 |

| Basophils | 0.04 (0.02–0.08) | 0.03 (0.02–0.07) | 0.226 |

| T-cells | 1.16 (0.66–1.61) | 0.86 (0.59–1.25) | 0.005 |

| Helper T-cells | 0.77 (0.45–1.14) | 0.55 (0.38–0.92) | 0.013 |

| Cytotoxic T-cells | 0.37 (0.18–0.68) | 0.28 (0.16–0.39) | 0.041 |

| Natural killer cells | 0.24 (0.12–0.41) | 0.20 (0.08–0.46) | 0.264 |

| DR+ T-cells | 0.075 (0.032–0.170) | 0.054 (0.037–0.145) | 0.218 |

| B-cells | 0.19 (0.08–0.38) | 0.19 (0.08–0.44) | 0.595 |

| CD14+ cells | 0.68 (0.39–1.13) | 0.83 (0.45–1.17) | 0.308 |

| DR+ monocytes | 0.63 (0.37–0.97) | 0.62 (0.41–0.94) | 0.976 |

| CD16+ monocytes | 0.087 (0.041–0.159) | 0.107 (0.044–0.161) | 0.286 |

| Calprotectin | 6.0 (2.9–10.7) | 5.7 (3.9–12.7) | 0.383 |

| Inflammatory response 3–7 days after stroke | |||

| Variable | Outcome after 3 months | P* | |

| mRS 0–2 (n=49) | mRS 3–6 (n=56) | ||

| WBC | 8.1 (5.8–11.4) | 9.6 (6.6–13.7) | 0.061 |

| Neutrophils | 5.3 (3.1–7.9) | 6.8 (4.1–10.7) | 0.002 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.73 (1.29–2.78) | 1.47 (0.88–2.28) | 0.013 |

| Monocytes | 0.81 (0.48–1.18) | 0.88 (0.57–1.25) | 0.345 |

| Eosinophils | 0.20 (0.03–0.42) | 0.18 (0.04–0.35) | 0.231 |

| Basophils | 0.04 (0.02–0.08) | 0.04 (0.02–0.08) | 0.487 |

| T-cells | 1.27 (0.90–1.94) | 1.08 (0.64–1.56) | 0.006 |

| Helper T-cells | 0.81 (0.59–1.23) | 0.73 (0.36–1.06) | 0.006 |

| Cytotoxic T-cells | 0.38 (0.19–0.82) | 0.33 (0.16–0.62) | 0.090 |

| Natural killer cells | 0.25 (0.13–0.41) | 0.20 (0.10–0.38) | 0.127 |

| DR+ T-cells | 0.09 (0.04–0.19) | 0.07 (0.03–0.17) | 0.127 |

| B-cells | 0.19 (0.11–0.47) | 0.18 (0.06–0.38) | 0.243 |

| CD14+ cells | 0.66 (0.37–0.96) | 0.77 (0.48–1.17) | 0.114 |

| DR+ monocytes | 0.62 (0.35–0.92) | 0.65 (0.43–0.97) | 0.259 |

| CD16+ monocytes | 0.086 (0.036–0.198) | 0.103 (0.043–0.160) | 0.311 |

| Calprotectin | 5.8 (2.5–10.9) | 6.0 (4.3–12.6) | 0.066 |

P-values of the Mann-Whitney U test were computed to compare patients with different outcomes.

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

Table 6.

Inflammatory responses.

| Inflammatory response | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Time of measurement | P* | |

| Entry | After 3–7 days | ||

| WBC | 9.1 (6.1–13.0) | 8.8 (6.2–12.9) | 0.113 |

| Neutrophils | 6.8 (4.4–11.0) | 5.8 (3.9–9.9) | <0.001 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.23 (0.72–2.16) | 1.67 (1.01–2.57) | <0.001 |

| Monocytes | 0.58 (0.35–0.96) | 0.83 (0.52–1.27) | <0.001 |

| Eosinophils | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.2 (0.0–0.4) | <0.001 |

| Basophils | 0.04 (0.02–0.07) | 0.04 (0.02–0.08) | 0.654 |

| T-cells | 0.82 (0.43–1.50) | 1.15 (0.66–1.70) | <0.001 |

| Helper T-cells | 0.50 (0.27–1.01) | 0.75 (0.42–1.15) | <0.001 |

| Cytotoxic T-cells | 0.26 (0.11–0.54) | 0.35 (0.18–0.70) | 0.003 |

| Natural killer cells | 0.19 (0.09–0.46) | 0.23 (0.12–0.42) | 0.218 |

| DR+ T-cells | 0.061 (0.027–0.138) | 0.072 (0.033–0.173) | 0.052 |

| B-cells | 0.14 (0.06–0.29) | 0.19 (0.08–0.42) | <0.001 |

| CD14+ cells | 0.48 (0.28–0.80) | 0.71 (0.41–1.17) | <0.001 |

| DR+ monocytes | 0.45 (0.27–0.76) | 0.62 (0.38–0.95) | <0.001 |

| CD16+ monocytes | 0.039 (0.016–0.091) | 0.093 (0.039–0.162) | <0.001 |

| Calprotectin | 4.9 (2.6–9.8) | 5.8 (2.9–11.1) | 0.043 |

| Inflammatory response 3–7 days after stroke | |||

| Variable | Treatment in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score | P** | |

| 0-1 | 2-3 | ||

| WBC | 11.2 (7.3–13.7) | 8.5 (6.0–12.8) | 0.019 |

| Neutrophils | 8.3 (5.1–11.0) | 5.6 (3.8–9.3) | 0.006 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.2 (1.0–2.9) | 1.7 (1.0–2.5) | 0.307 |

| Monocytes | 0.90 (0.65–1.27) | 0.82 (0.50–1.26) | 0.426 |

| Eosinophils | 0.11 (0.03–0.27) | 0.19 (0.04–0.42) | 0.289 |

| Basophils | 0.04 (0.02–0.07) | 0.04 (0.02–0.08) | 0.454 |

| T-cells | 0.92 (0.60–1.96) | 1.15 (0.70–1.68) | 0.244 |

| Helper T-cells | 0.67 (0.39–1.14) | 0.75 (0.43–1.15) | 0.478 |

| Cytotoxic T-cells | 0.23 (0.18–0.83) | 0.37 (0.18–0.68) | 0.095 |

| Natural killer cells | 0.25 (0.06–0.42) | 0.22 (0.12–0.42) | 0.908 |

| DR+ T-cells | 0.049 (0.040–0.266) | 0.074 (0.032–0.172) | 0.490 |

| B-cells | 0.20 (0.13–0.38) | 0.19 (0.08–0.42) | 0.631 |

| CD14+ cells | 0.80 (0.55–1.18) | 0.69 (0.40–1.16) | 0.289 |

| DR+ monocytes | 0.60 (0.46–0.93) | 0.63 (0.37–0.95) | 0.694 |

| CD16+ monocytes | 0.114 (0.055–0.180) | 0.087 (0.039–0.162) | 0.242 |

| Calprotectin | 6.4 (3.4–11.3) | 5.8 (2.7–11.0) | 0.387 |

P-values of the paired sign test were computed to compare the inflammatory response at different time points;

P-values of the Mann-Whitney U test were computed to compare patients with different outcome.

In the evaluation of vWF levels, patient blood type was also a consideration [33]. In the patient study population, significantly lower vWF levels (P=0.007) were observed in patients with the O-blood type (median: 178; IDR: 117–263) compared with patients with other blood types (median: 207; IDR: 145–348). No significant difference (P=0.362) in vWF levels were found between patients with a TICI score of 0-1 (median: 197; IDR: 151–411) and patients with a TICI score of score of 2–3 (median: 198; IDR: 135–326). There was a slight, but non-significant, increase in vWF levels in patients older than 65 years (median: 203; IDR: 137–325) compared with patients younger than 65 years (median: 181; IDR: 131–342) (P=0.153). Also, no significant difference in vWF levels (P=0.62) was found between patients with arrhythmia (median: 199; IDR: 145–303) when compared with patients without arrhythmia (median: 198; IDR: 131–374). The Spearman’s correlation coefficient between vWF levels and procedure duration was not significant (r=0.02). An increased systemic inflammatory response did not explain the increased vWF levels in patients with a poorer clinical outcome, as C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were not significantly different (Tables 3, 4).

Significantly increased levels of D-dimers (P=0.029) were observed in patients with three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 3–6 (median: 4.4; IDR: 0.8–26.0) compared with patients with three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 0–2 (median: 2.6; IDR: 0.7–10.7) (Table 4). Patients older than 65 years had significantly higher D-dimer levels (P=0.022; median: 4.0; IDR: 0.9–25.1) than did younger patients (median: 2.6; IDR: 0.7–9.6). Patients with arrhythmia (n=51) had slightly diminished D-dimer values (median: 2.4; IDR: 0.8–19.3) than did those without arrhythmia (n=75; median 3.5; IDR: 0.8–19.2) (P=0.18), possibly because some patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) were on warfarin therapy.

There was no significant difference in ADAMTS13 levels between patients with an NIHSS score >15 and patients with an NIHSS score ≤15 (P=0.601) (Table 3). No significant difference in ADAMTS13 levels was found in patients with TICI scores of 0–1 when compared with patients with TICI scores of 2–3 (P=0.258). However, patients with three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 3–6 had significantly increased levels of ADAMTS13 (P=0.047) (median: 78; IDR: 20–101) compared with patients with three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 0–2 (median: 66; IDR: 15–93) (Table 4). Also, patients with severe neurological deficit, who has an NIHSS >15 before starting the mechanical interventional procedure had significantly increased vWF: ADAMTS13 ratios (P=0.038) (median: 3.0; IDR: 1.9–15.9) compared with the vWF: ADAMTS13 ratio in patients who has an NIHSS ≤15 (median: 2.5; IDR: 1.5–7.9) (Table 3).

Inflammatory response

Ischemia caused vascular thrombosis or thromboembolism results in serious homeostatic disruption of the affected tissue that results in an immune response. Following removal of the thrombus from the cerebral arteries supplying the brain, the total WBC count decreased slightly from the time of the procedure (median: 9.1; IDR: 6.1–13.0) to 2–5 days after mechanical removal (median: 8.8; IDR: 6.2–12.9) because of a significant decline in neutrophil count (P<0.001) from median 6.8 (IDR: 4.4–11.0) to median 5.8 (IDR: 3.9–9.9). The cell counts of monocytes, which are antigen-presenting cells, and their activated forms progressively increased, and cell counts of lymphocytes and eosinophils modulating the adaptive and immediate hypersensitivity reaction were also increased (Table 6).

Patients with a TICI score of 2–3 had an improved outcome, and had a significantly lower neutrophil count (P=0.006) (median: 5.6; IDR: 3.8–9.3) 5 ± 2 days after the procedure, compared with patients with a TICI score of 0–1 (median: 8.3; IDR: 5.1–11.0 (Table 6). This outcome corresponded to a significantly increased neutrophil count (P=0.002) in patients with NIHSS >15, 5±2 days after the procedure (median: 9.1; IDR: 4.6–11.0) compared with patients with NIHSS ≤15 (median: 5.7; IDR: 3.8–9.0). The cell counts of total T-cells, helper T-cells, and cytotoxic T-cells were significantly lower (P=0.005, P=0.013, P=0.041, respectively) in patients with NIHSS >15 compared with those with NIHSS ≤15. The same trend was observed for cell counts of total T-cells and their subpopulation of helper T-cells between patients with three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 3–6 and three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 0–2 (P=0.006 and P=0.006, respectively) (Table 5).

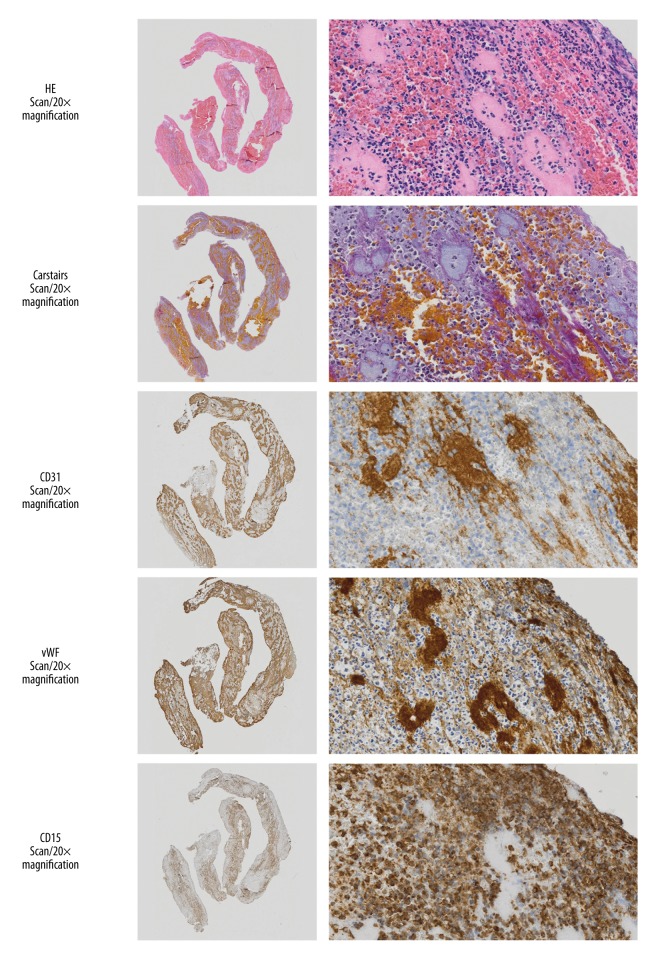

Histopathology of the thrombus

Recanalization of the cerebral artery was successful in 115/131 patients (89%) from whom, 90 samples of thrombus were extracted, fixed, sectioned and analyzed histologically by light microscopy (Figure 3). From these samples of thrombus, it was possible to analyze five different areas in 79 samples via Carstairs’ histochemical staining technique for platelets, which involved measuring the area of positive staining digitally on the image displayed on the monitor. The same method was used to analyze 84 samples (with more than three measurements from a single sample) for the immunostaining for the CD31 marker and 85 samples were analyzed immunohistochemically for the vWF marker. The analysis of the cellular composition of the extracted thrombi was done with the data from the use of intravenous thrombolysis administration prior to thrombectomy, TICI recanalization output, three-month modified Rankin Scale scores outcome, and plasma vWF measurements.

Figure 3.

Histopathology analysis. Photomicrographs in the left column show the light microscopic appearance of thrombus viewed by an Olympus dotSlide BX51 virtual microscope (×20). In the right column, photomicrographs show selected sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and show a large number of neutrophils in the surface of the thrombus. Carstairs’ histochemical staining method for fibrin and platelets shows fibrin in orange-red, and platelets in light grey. Immunohistochemistry for the endothelial cell marker, CD31, is stained light blue; positive immunohistochemistry staining for von Willebrand factor (vWF) was mainly located at the thrombus surface, with granulocytes near the vWF-stained areas. Immunohistochemical staining for CD15 is positive for myelomonocytes (neutrophils and eosinophils).

A large number of neutrophils were present in the surface layer of the extracted arterial thrombus (Figure 3). These thromboemboli also had an increased area of vWF-positive immunostaining (Figure 3). A significantly increased number of platelets were present in the mechanically extracted thrombi in patients with a TICI score of 2–3 compared with those with a TICI score of 0–1 (P=0.003). Thrombus samples from patients previously treated with intravenous thrombolysis had less fibrin (P=0.04) and fewer CD31-positive cells (P=0.056), although the reduction in CD31-positive immunostaining was not statistically significant.

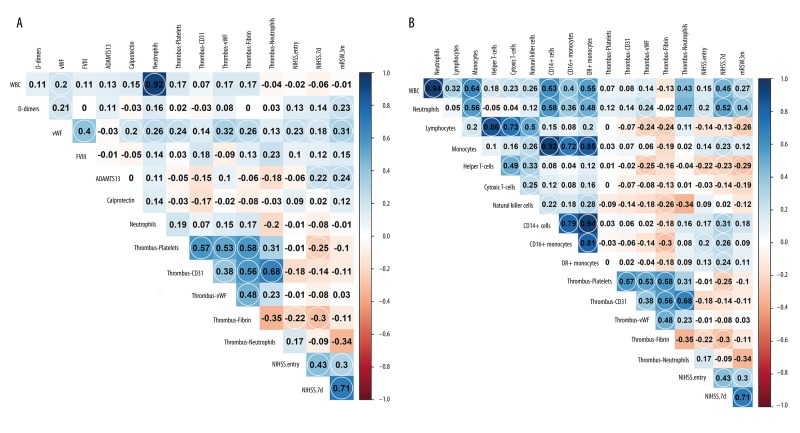

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients showed a significant relationship between plasma vWF and the vWF found in the thromboembolus (r=0.32), platelets (r=0.24), or fibrin (r=0.26). Also, in the thromboembolus structure, the area of immunostained vWF correlated with platelet count (r=0.53), CD31-positive cells (r=0.38), and fibrin (r=0.48), as did the amount of all CD31-positive cells with the number of neutrophils in the thrombus (r=0.68) (Figure 4.A). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient showed a significantly positive relationship between D-dimer levels and plasma vWF levels (r=0.21), as well as three-month modified Rankin Scale scores (r=0.23) (Figure 4A). Also, there were significant correlations between blood neutrophil levels and vWF levels within the thrombus (r=0.24), the numbers of natural killer (NK) cells and the fibrin content of the thrombus (r=−0.26), and the numbers of lymphocytes and the fibrin content of the thrombus (r=−0.24) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Correlations between hemocoagulation, immune response, histology, and clinical outcome. (A) Significant correlations between hemocoagulation analysis and histology, and between von Willebrand factor (vWF) and thrombotic parameters: platelets, vWF, and fibrin levels. These parameters are significantly correlated with each other. (B) Histology and the inflammatory response shows a significant correlation with fibrin thrombus and inflammatory response parameters. Significant correlation coefficients are circled (level of significance 0.05).

Discussion

The aim of the study was to evaluate the role of von Willebrand factor (vWF), the vWF-cleaving protease, ADAMTS13, the composition of thrombus, and patient outcome following mechanical cerebral artery thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Successful recanalization with a Treatment in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score of 2–3 of the large vessel occlusion was obtained in 89% (115/131) of patients, with a good clinical outcome as shown by three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 0–2 in 47% (49/131) of cases. There was no significant difference in clinical outcome between patients with or without previous administration of intravenous thrombolysis for large vessel cerebral artery thromboembolic occlusion treated with mechanical thrombectomy, and no significant difference in patient outcome between the types of mechanical extraction device used. The TICI score of 2–3 played an important role in the clinical evaluation of patients in this study and was associated with a significantly improved clinical outcome following mechanical cerebral artery thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

The findings of this study identified significantly increased plasma vWF in patients with worse clinical findings when assessed by the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) who had a score >15 before the mechanical thrombectomy procedure and in patients with a three-month modified Rankin Scale scores of 3–6, three months after the treatment. In addition to these findings, this study showed that an increased level of vWF in the removed thromboembolic material was significantly associated with a worse patient clinical condition before the interventional procedure and a worse clinical outcome at three months following the mechanical intervention. These findings are supported by previously published studies that have shown an increased vWF level to be an independent risk factor for thrombus formation, for example in the left atrium, and thromboembolic stroke [24,34,35].

Reduction of ADAMTS13 activity occurs because of increased consumption, which may affect the degradation of ultra-large vWF multimers, which can influence vWF behavior [25]. In connection with an elevated vWF level, the vWF: ADAMTS13 ratio in this study was significantly increased in patients with a worse clinical outcome, and an NIHSS score >15 at the time of stroke onset, compared with patients with an NIHSS score ≤15. Small changes in ADAMTS13 activity are unlikely to have affected these results, and the implication is that in patients with acute thromboembolic ischemic stroke following mechanical intervention, daily monitoring of vWF levels might be sufficient, but with consideration of the limited specificity of total vWF, which can be increased in patients with other clinical conditions, such as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension [20,36,37].

In this study, the evaluation of D-dimers was shown to be affected by patient age, which is a finding supported by previously published studies [38,39]. In this study, decreased D-dimer values in patients with arrhythmia probably resulted from warfarin therapy, at least in some cases [40,41]. D-dimer levels on hospital admission were significantly increased in patients with a three-month modified Rankin Scale score of 3–6, compared with patients with a three-month modified Rankin Scale score of 0–2. The explanation for this study finding is likely to be due to an increased prothrombotic state in the location of thrombus formation, for example, in the left atrium, damage to the vascular wall, and tissue around the occluding embolus and, of course, due to intravenous thrombolysis therapy [42].

The primary immune response is provided by cells of the myeloid cell line, including granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils), monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells, as well as megakaryocytes that release blood platelets. Innate immune responses provided by lymphoid cells and natural killer (NK) cells are also involved in the early phases of the immune and inflammatory response. Neutrophils, as an early-stage phagocyte, are activated on the surface of the newly-formed thrombus, as well as on the surface of the organising thrombus, and embolic thrombus, inducing the release of cytokines, chemokines, reactive oxygen species, as well as neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and neutrophil apoptosis or NETosis, and calprotectin, all of which have a strong antibacterial effect. Calprotectin comprises up to 60% of the cytoplasmic neutrophil content.

In this study, comparison of the plasma levels of vWF, and some selected components of the extracted thrombi, showed that plasma vWF levels were significantly correlated with the increasing vWF content of the embolic thrombi, a finding which has been previously supported in studies that have shown vWF levels to be an independent risk factor for thrombus formation and stroke [43]. Embolic vWF content has also been shown to correlate with platelet count and fibrin levels, possibly because vWF at the site of the incipient thrombus can capture larger numbers of activated platelets [43]. These findings are in agreement with reports of larger platelet-rich areas in embolized thrombi (39% versus 19% in thrombi in the left atrium) and platelet-rich emboli extracted from the cerebral arteries of stroke patients [44–47]. Previously published studies have also found a high fibrin content in peripheral artery thrombi and increased expression of platelet factor XIII (F13A1) in thrombi from the left atrium compared with embolized thrombi, confirming the role of platelets in the stabilization of fibrin thrombus [48].

Finally, in this study the amount of vWF in embolized thrombus correlated with CD31 immunopositivity, which correlated with thrombus neutrophil content. Larger amounts of vWF around the nascent thrombus could bind larger numbers of neutrophils, recruited to the activated endothelium [49,50]. Co-expression of fibrin and NETosis has previously been demonstrated in arterial thrombi in patients with ischemic stroke [51–53].

Conclusions

In this study population, with cerebral artery thromboembolic occlusion leading to acute ischemic stroke, mechanical thrombectomy resulted in an increased Treatment in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score of 2–3 for the outcome of vessel recanalization in 89% of patients, and good clinical outcome was shown by a three-month modified Rankin Scale score of 0–2 in 47% of cases. Patients with worse clinical outcome had significantly increased levels of von Willebrand Factor (vWF) and the vWF: ADAMTS13 ratio was significantly increased in patients with a worse outcome at the time of onset of ischemic stroke. Increased plasma levels of vWF were associated with vWF-rich thrombus from cerebral arteries of patients with stroke, which were also platelet-rich, fibrin-rich, and neutrophil-rich. Patients treated with or without intravenous thrombolysis did not differ in terms of the three-month modified Rankin Scale score for clinical outcome.

Footnotes

Source of support: This work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Institutional Grant (DRO-FNOs/2016)

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1019–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2285–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1009–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2296–306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heshmatollah A, Fransen PSS, Berkhemer OA, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation. A MR CLEAN subgroup analysis. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:996–1002. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-16-00905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Solitaire with the intention for thrombectomy as primary endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke (SWIFT PRIME) trial: Protocol for a randomized, controlled, multicenter study comparing the Solitaire revascularization device with IV tPA with IV tPA alone in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:439–48. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kidwell CS, Jahan R, Alger JR, et al. Design and rationale of the mechanical retrieval and recanalization of stroke clots using embolectomy (MR RESCUE) Trial. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:110–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387:1723–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaidi SF, Aghaebrahim A, Urra X, et al. Final infarct volume is a stronger predictor of outcome than recanalization in patients with proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion treated with endovascular therapy. Stroke. 2012;43:3238–44. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.671594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacIsaac RL, Khatri P, Bendszus M, et al. A collaborative sequential meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomized trials of endovascular therapy and tPA vs. tPA alone for acute ischemic stroke: ThRombEctomy And tPA (TREAT) analysis: Statistical analysis plan for a sequential meta-analysis performed within the VISTA-Endovascular collaboration. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(Suppl A100):136–44. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fargen KM, Neal D, Fiorella DJ, et al. A meta-analysis of prospective randomized controlled trials evaluating endovascular therapies for acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7:84–89. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elgendy IY, Kumbhani DJ, Mahmoud A, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez-Fernandez F, Rojas-Bartolome L, Garcia-Garcia J, et al. Histopathological and bacteriological analysis of thrombus material extracted during mechanical thrombectomy in acute stroke patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40:1851–60. doi: 10.1007/s00270-017-1718-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuhmann MK, Gunreben I, Kleinschnitz C, Kraft P. Immunohistochemical analysis of cerebral thrombi retrieved by mechanical thrombectomy from patients with acute ischemic stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:298. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iadecola C, Anrather J. The immunology of stroke: From mechanisms to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17:796–808. doi: 10.1038/nm.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wysokinski WE, Owen WG, Fass DN, et al. Atrial fibrillation and thrombosis: Immunohistochemical differences between in situ and embolized thrombi. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1637–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson T, Arya A, Sulke N, Lip GY. Relationship of indices of inflammation and thrombogenesis to arrhythmia burden in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:869–76. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denorme F, Langhauser F, Desender L, et al. ADAMTS13-mediated thrombolysis of t-PA-resistant occlusions in ischemic stroke in mice. Blood. 2016;127:2337–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-662650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawecki C, Lenting PJ, Denis CV. von Willebrand factor and inflammation. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:1285–94. doi: 10.1111/jth.13696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruggeri ZM. The role of von Willebrand factor in thrombus formation. Thromb Res. 2007;120(Suppl 1):S5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bongers TN, de Maat MP, van Goor ML, et al. High von Willebrand factor levels increase the risk of first ischemic stroke: Influence of ADAMTS13, inflammation, and genetic variability. Stroke. 2006;37:2672–77. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000244767.39962.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan MM, Motto DG, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. ADAMTS13 reduces VWF-mediated acute inflammation following focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1665–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ammash N, Konik EA, McBane RD, et al. Left atrial blood stasis and Von Willebrand factor-ADAMTS13 homeostasis in atrial fibrillation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2760–66. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.232991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong JF. Cleavage of ultra-large von Willebrand factor by ADAMTS13 under flow conditions. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1710–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu H, Cao Y, Yang X, et al. ADAMTS13 controls vascular remodeling by modifying VWF reactivity during stroke recovery. Blood. 2017;130:11–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-747089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.De Meyer SF, Stoll G, Wagner DD, Kleinschnitz C. von Willebrand factor: An emerging target in stroke therapy. Stroke. 2012;43:599–606. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.628867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo GP, Ni B, Yang X, Wu YZ. von Willebrand factor: More than a regulator of hemostasis and thrombosis. Acta Haematol. 2012;128:158–69. doi: 10.1159/000339426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gragnano F, Sperlongano S, Golia E, et al. The role of von Willebrand factor in vascular inflammation: From pathogenesis to targeted therapy. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:5620314. doi: 10.1155/2017/5620314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Striz I, Trebichavsky I. Calprotectin – a pleiotropic molecule in acute and chronic inflammation. Physiol Res. 2004;53:245–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Meyer SF, Andersson T, Baxter B, et al. Analyses of thrombi in acute ischemic stroke: A consensus statement on current knowledge and future directions. Int J Stroke. 2017;12:606–14. doi: 10.1177/1747493017709671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simons N, Mitchell P, Dowling R, et al. Thrombus composition in acute ischemic stroke: A histopathological study of thrombus extracted by endovascular retrieval. J Neuroradiol. 2015;42:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2014.01.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sousa NC, Anicchino-Bizzacchi JM, Locatelli MF, et al. The relationship between ABO groups and subgroups, factor VIII and von Willebrand factor. Haematologica. 2007;92:236–39. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conway DS, Pearce LA, Chin BS, et al. Prognostic value of plasma von Willebrand factor and soluble P-selectin as indices of endothelial damage and platelet activation in 994 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;107:3141–45. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000077912.12202.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukuchi M, Watanabe J, Kumagai K, et al. Increased von Willebrand factor in the endocardium as a local predisposing factor for thrombogenesis in overloaded human atrial appendage. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1436–42. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyseni A, Kemperman H, de Lange DW, et al. Active von Willebrand factor predicts 28-day mortality in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Blood. 2014;123:2153–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-508093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groot E, de Groot PG, Fijnheer R, Lenting PJ. The presence of active von Willebrand factor under various pathological conditions. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:284–89. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3280dce531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tita-Nwa F, Bos A, Adjei A, et al. Correlates of D-dimer in older persons. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2010;22:20–23. doi: 10.1007/bf03324810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harper PL, Theakston E, Ahmed J, Ockelford P. D-dimer concentration increases with age reducing the clinical value of the D-dimer assay in the elderly. Intern Med J. 2007;37:607–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christersson C, Wallentin L, Andersson U, et al. D-dimer and risk of thromboembolic and bleeding events in patients with atrial fibrillation – observations from the ARISTOTLE trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1401–12. doi: 10.1111/jth.12638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Habara S, Dote K, Kato M, et al. Prediction of left atrial appendage thrombi in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2217–22. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahe I, Drouet L, Chassany O, et al. A characteristic of the coagulation state of each patient with chronic atrial fibrillation. Thromb Res. 2002;107:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(02)00184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brill A, Fuchs TA, Chauhan AK, et al. von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet adhesion is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mouse models. Blood. 2011;117:1400–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-287623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almekhlafi MA, Hu WY, Hill MD, Auer RN. Calcification and endothelialization of thrombi in acute stroke. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:344–48. doi: 10.1002/ana.21404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liebeskind DS, Sanossian N, Yong WH, et al. CT and MRI early vessel signs reflect clot composition in acute stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:1237–43. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marder VJ, Chute DJ, Starkman S, et al. Analysis of thrombi retrieved from cerebral arteries of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:2086–93. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000230307.03438.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niesten JM, van der Schaaf IC, van Dam L, et al. Histopathologic composition of cerebral thrombi of acute stroke patients is correlated with stroke subtype and thrombus attenuation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gosk-Bierska I, McBane RD, Wu Y, et al. Platelet factor XIII gene expression and embolic propensity in atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:75–82. doi: 10.1160/TH10-11-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Bruhl ML, Stark K, Steinhart A, et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. J Exp Med. 2012;209:819–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Downing LJ, Strieter RM, Kadell AM, et al. Neutrophils are the initial cell type identified in deep venous thrombosis induced vein wall inflammation. ASAIO J. 1996;42:M677–82. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199609000-00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Longstaff C, Varju I, Sotonyi P, et al. Mechanical stability and fibrinolytic resistance of clots containing fibrin, DNA, and histones. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6946–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.404301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oklu R, Albadawi H, Watkins MT, et al. Detection of extracellular genomic DNA scaffold in human thrombus: Implications for the use of deoxyribonuclease enzymes in thrombolysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:712–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laridan O, Denorme F, Desender L, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ischemic stroke thrombi. Ann Neurol. 2017;82:223–32. doi: 10.1002/ana.24993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]