Abstract

Objectives

Bone loss is a well-established consequence of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). To date, bone disease in RA is exclusively characterised by bone density measurements, while the functional properties of bone in RA are undefined. This study aimed to define the impact of RA on the functional properties of bone, such as failure load and stiffness.

Methods

Micro-finite element analysis (µFEA) was carried out to measure failure load and stiffness of bone based on high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT data from the distal radius of anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-positive RA (RA+), ACPA-negative RA (RA−) and healthy controls (HC). In addition, total, trabecular and cortical bone densities as well as microstructural parameters of bone were recorded. Correlations and multivariate models were used to determine the role of demographic, disease-specific and structural data of bone strength as well as its relation to prevalent fractures.

Results

276 individuals were analysed. Failure load and stiffness (both P<0.001) of bone were decreased in RA+, but not RA−, compared with HC. Lower bone strength affected both female and male patients with RA+, was related to longer disease duration and significantly (stiffness P=0.020; failure load P=0.012) associated with the occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. Impaired bone strength was correlated with altered bone density and microstructural parameters, which were all decreased in RA+. Multivariate models showed that ACPA status (P=0.007) and sex (P<0.001) were independently associated with reduced biomechanical properties of bone in RA.

Conclusion

In summary, µFEA showed that bone strength is significantly decreased in RA+ and associated with fractures.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, bone strength, fracture, micro-finite element analysis

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory joint disease associated with bone destruction and increased fracture risk.1 2 While traditionally most attention in RA-related bone disease is drawn to periarticular bone erosions forming, the development of generalised bone loss in RA is of no less importance as it precipitates the increased fracture risk immanent to patients with RA.3 4 Accumulating evidence suggests that bone loss in RA is driven to a large extent by the presence of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA), which enhance osteoclastogenesis and thereby accelerate skeletal disease.5–11 In support of this concept, there is good clinical evidence that local bone disease is more pronounced in patients with RA with ACPA9 11 and also some evidence for more severe systemic bone loss.10

Although several studies have documented the loss of bone mass in patients with RA and some studies provided evidence for both cortical and trabecular bone loss in RA,11 the functional impact of these structural changes for the stability of bone in RA are yet unknown. Hence, while we perceive that fracture risk is increased in RA, we do not really know whether the morphological changes of bone recorded in radiographic studies are indeed impacting the stability of bone. Micro-finite element analysis (µFEA) is a novel technique, which is increasingly used to characterise the biomechanical properties of bone and relate them to its microstructure.12–14 This technique has been developed based on the availability of high-quality bone structure analyses in humans in vivo using high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT (HR-pQCT) scanners.15–18 µFEA uses these data and mathematically models stiffness and failure load of the radius during a fall on the outstretched hand. Studies performed in healthy individuals have shown that µFEA accurately predicts bone strength and also allows better identification of individuals with fragility fractures than it can be achieved by the measurement of bone density.14

Hence, µFEA constitutes an attractive technology to better characterise the impact of bone changes in patients with systemic inflammatory diseases. ACPA-positive RA represents a paradigm disease to study µFEA as it is associated by changes in the bone microstructure and complicated by increased fracture risk. To characterise the mechanical properties of bone in RA, we applied µFEA in a cohort of patients with ACPA-positive RA (RA+) and ACPA-negative RA (RA−) and compared bone strength and stiffness of the distal radius of patients with RA+ and RA− with healthy controls. Furthermore, we aimed to define the demographic, disease-related and bone structural factors that are associated with bone strength in ACPA-positive RA. Finally, µFEA results were also related to fragility fractures in patients with ACPA-positive RA.

Methods

Patients with RA and controls

Healthy controls (HC) and patients with RA were part of the Erlangen Imaging Cohort (ERIC), which prospectively assesses bone composition in healthy individuals and patients with inflammatory arthritis.19 In ERIC, 225 patients with RA were imaged in 2015 and 2016, 180 of them (80%) had motion grades 1–3 allowing proper analysis of bone structural parameters (16). The 180 analysed patients were representative for the entire cohort with similar sex, age and disease-specific parameters. All participants were recruited at the Department of Internal Medicine 3 of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and were clinically examined by an experienced rheumatologist (AK, JR, AJH). Patients with RA+ and RA− fulfilling the 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria were recruited. HC had to have (1) no signs of joint pain or swelling, (2) no presence of inflammatory or other chronic diseases, (3) no documented osteopaenia, osteoporosis or low-impact fracture or present/past use of bisphosphonates or prednisolone and (4) no positive test for autoantibodies such as ACPA or rheumatoid factor.19 Demographic (age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status) and disease-specific (disease duration, disease activity by Disease Activity Score-28, physical function by Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), prednisolone and bisphosphonates, ACPA positivity and rheumatoid factor positivity) data were recorded. Fracture status was documented differentiating high-impact (sport injuries and accidents) from low-impact fractures (spontaneous or fall from walking or standing position). The study was conducted on approval of the local ethics committee of the University Clinic of Erlangen and with the authorisation of the National Radiation Safety Agency (Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz). Each individual provided informed consent.

HR-pQCT measurement

HR-pQCT was performed at the distal radius of the dominant hand by XtremeCT I scanner (Scanco Medical) using the manufacturer’s default protocol for in vivo patient imaging. Measurements were carried out with an offset of 9.5 mm proximal to the reference line, which was manually set.15 16 19 An anterior–posterior scout view determined the region of interest. One hundred eleven slices (82 µm nominal isotropic voxel size, 60 kVp effective energy, 900 µA) were taken. Standard analysis software (V.6.0) was used to determine the following density parameters: volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD) of total (Dtotal), trabecular (Dtrab), meta-trabecular (Dmeta), inner-trabecular (Dinn) and cortical bone (Dcomp (all in mg HA/cm³)), ratio of meta-to-inner density (Meta/Inn, %) and cross-sectional bone area (mm²).15 16 Bone microstructure was evaluated by determining trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV, %), trabecular number (Tb.N (1/mm)), thickness (Tb.Th (mm)), separation (Tb.Sp (mm)), network inhomogeneity (SD of 1/trabecular number, Tb.1/N.SD (mm)) as well as cortical thickness (Ct.Th (mm)).15 16

Micro-finite element analysis

For µFEA, finite element analysis software (FAIM, V.8.0; Numerics88 Solution, Calgary, Canada) was used. In order to generate micro-finite element models, the segmented trabecular network and cortex of the HR-pQCT images were used.20 Mesh size of the resulting models ranged from 1.5 to 3.5 million equally sized brick elements. Single linear isotropic tissue modelling was applied by assigning a tissue modulus of 6829 MPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3 homogeneously to each element.13 A linear uniaxial compression test was simulated. Nodes on the proximal bone surface were fixed in z direction but unconstrained in x and y directions. Nodes on the distal bone surface were also free in x and y direction but exposed to a displacement equivalent to 1% strain along the z-axis.13 Axial bone stiffness (kN/mm) as reaction force (RFz) divided by average displacement of the distal surface (Uz) and bone strength as estimated failure load (N) based on the Pistoia criterion was calculated.12

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed to test whether (1) groups (RA+, RA−, HC) were comparable with respect to demographic and disease-specific parameters, (2) bone strength and structural parameters differed among the groups and (3) sex and disease duration influence bone strength. In addition, we aimed to define independent factors associated with bone strength in the total population as well as in patients with RA+. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS V.21.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Categorical variables are provided as numbers and percentages, continuous variables as mean±SD. Differences in frequency distributions of categorical variables were tested using χ2 inferential tests. Assumptions of normally distributed continuous variables were tested using quantile–quantile plots as well as Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk test. Clinical, bone structural and µFEA parameters were compared by using Kruskal-Wallis test (KW) with subsequent pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests, if KW test was significant. For correlating vBMD data with bone strength, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs) was used. In order to account for multiple testing, we applied Bonferroni-Holm adjustment for subgroup comparisons. Critical P values for adjusted levels of significance are shown in the corresponding tables. For all other comparisons, P values ≤0.05 were considered significant; all inferential tests were two-tailed. The direction of differences and relations is indicated by descriptive additional information or test coefficients.

To determine factors for bone strength in patients with RA, two multiple linear regression models using forced entry method for predictor inclusion were calculated in the RA patient subgroup. In the first model, we chose failure load as dependent variable, whereas in the second model stiffness was selected to be the dependent variable. In both models, sex, age, BMI, disease duration, biological DMARD use and ACPA status were entered as independent variables. In the third and fourth linear regression models, the total sample, consisting of healthy controls and patients with RA+ and RA−, was included, whereas failure load and stiffness, respectively, were selected as dependent variables while sex, age, BMI, biological DMARD use (for healthy controls set to no) and ACPA entity (dummy coded with healthy participants being the reference) were entered as independent variables. In regression models 3 and 4, information on ACPA status is reflected by the dummy coding procedure, that is, the coding scheme for RA+ versus HC is congruent to ACPA status in models 1 and 2.

Results

Characteristics of patients and controls

A total of 276 Caucasian individuals (96 RA+, 84 RA− and 96 HC) were analysed. Age and sex distributions were not significantly different between the three groups. Smoking was more frequent among patients with RA+ (RA+: 24.0% vs HC: 7.3%, P=0.001), while BMI was higher in the RA+ (26.2±5.1; P=0.009) and RA− groups (26.8±5.8; P=0.007) than in HC (24.5±3.7). RA+ and RA− groups did not significantly differ in disease duration, disease activity, physical function and DMARD treatment. Detailed information on demographic and disease-specific characteristics are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of healthy controls and patients with rheumatoid arthritis

| HC | RA+ | RA− | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Sex (n male/n female) | 38/58 | 26/70 | 22/62 |

| Age (years; mean±SD) | 50.1±16.5 | 54.2±12.2 | 53.9±12.2 |

| BMI (mean±SD) | 24.5±3.7*† | 26.2±5.1* | 26.8±5.8† |

| Smokers (n; %) | 7 (7.3)* | 23 (24.0)* | 12 (14.3) |

| Disease-specific characteristics | |||

| Disease duration (years; mean±SD) | – | 9.7±8.9 | 7.1±7.2 |

| DAS28-ESR (units; mean±SD) | – | 3.3±1.6 | 3.2±1.3 |

| HAQ-DI (units; mean±SD) | – | 0.7±0.7 | 0.7±0.6 |

| ACPA positive (n; %) | – | 96 (100.0)‡ | 0 (0)‡ |

| RF positive (n; %) | – | 73 (76.0)‡ | 7 (8.3)‡ |

| Anti-rheumatic treatment | |||

| Glucocorticoids (n; %) | – | 34 (35.4) | 31 (36.9) |

| Methotrexate (n; %) | – | 39 (40.6) | 44 (52.4) |

| Other cDMARDs (n; %) | – | 10 (10.4) | 6 (7.1) |

| bDMARDs (n; %) | – | 44 (45.8) | 31 (36.9) |

| No current DMARD (n; %)§ | – | 22 (22.9) | 21 (25.0) |

| Anti-osteoporotic treatment | |||

| Vitamin D (n; %) | 4 (4.2)* | 36 (37.5)*‡ | 19 (22.6)‡ |

| Bisphosphonates (n; %) | 0* | 8 (8.3)* | 3 (3.6) |

*Significance between HC vs RA+.

†Significance between HC vs RA−.

‡Significance between RA+ vs RA−.

§Either treatment naïve or in drug-free remission.

ACPA, anti-citrullinated protein antibody; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; BMI, body mass index; cDMARD, conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; DAS28-ESR, Disease Activity Score 28 - Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; HC, healthy controls; RA+, anti-citrullinated protein autoantibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA); RA−, anti-citrullinated protein autoantibody-negative RA; RF, rheumatoid factor.

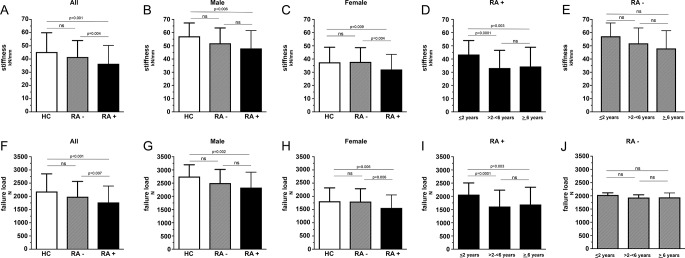

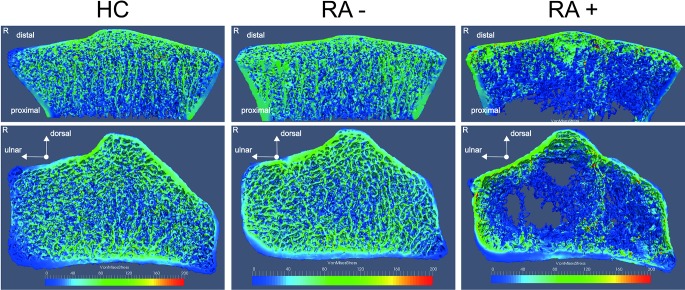

Bone strength is reduced in patients with RA+

We first analysed whether bone strength is impaired in patients with RA+ and patients with RA− compared with HC. When assessing bone biomechanical properties by µFEA, patients with RA+, but not RA−, showed significantly lower stiffness and failure load compared with HC (stiffness: 36.4±13.9 vs 45.3±14.6 kN/mm, P<0.001; failure load: 1771±619 vs 2184±667 N, P<0.001) (table 2, figure 1). Furthermore, when patients with RA+ were compared with patients with RA−, stiffness and failure load were significantly decreased in patients with RA+ (figure 1, table 2). Figure 2 shows representative images of µFEA analysis in RA+, RA− and HC.

Table 2.

Bone strength and structure in healthy controls and patients with rheumatoid arthritis

| HC | RA+ | RA− | |

| µFEA | |||

| Stiffness, kN/mm | 45.3±14.6* | 36.4±13.9*† | 41.5±12.5† |

| Failure load, N | 2184±667* | 1771±619*† | 1986±579† |

| Bone structure (HR-pQCT) | |||

| Volumetric bone mineral density | |||

| Dtotal, mg HA/cm³ | 289±56* | 256±58*† | 286±61† |

| Dtrab, mg HA/cm³ | 164±37*‡ | 130±47*† | 150±42†‡ |

| Dmeta, mg HA/cm³ | 223±37*‡ | 196±43*† | 207±41†‡ |

| Dinn, mg HA/cm³ | 124±39* | 98±44* | 110±44 |

| Dcomp, mg HA/cm³ | 786±66*‡ | 750±104*† | 814±69†‡ |

| Meta/Inn, % | 1.96±0.65* | 2.28±1.02* | 2.06±0.66 |

| Bone microstructure | |||

| BV/TV, % | 0.14±0.03*‡ | 0.12±0.04*† | 0.12±0.03†‡ |

| Tb.N, 1/mm | 2.04±0.30*‡ | 1.81±0.42*† | 1.93±0.37†‡ |

| TbTh, mm | 0.07±0.01* | 0.06±0.01* | 0.06±0.01 |

| Tb.Sp, mm | 0.44±0.11*‡ | 0.54±0.23*† | 0.49±0.21†‡ |

| Tb.1/N.SD, mm | 0.19±0.07*‡ | 0.29±0.24* | 0.23±0.15b |

| Ct.Th, mm | 0.67±0.18* | 0.59±0.21*† | 0.69±0.19† |

Bonferroni-Holm adjustment: critical P values indicating significant results for all investigated parameters were as follows: P1=0.0167, P2=0.025, P3=0.05.

*Significance between HC vs RA+.

†Significance between RA+ vs RA−.

‡Significance between HC vs RA−.

BV/TV, trabecular bone volume per tissue volume; Ct.Th, cortical thickness; Dcomp, compact (cortical) volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD); Dinn, inner trabecular vBMD; Dmeta, meta-trabecular vBMD; Dtotal, total vBMD; Dtrab, trabecular vBMD; HC, healthy controls; HR-pQCT, high-resolution peripheral CT; Meta/Inn, ratio of meta-to-inner density; RA+, anti-citrullinated protein autoantibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA); RA−, anti-citrullinated protein autoantibody-negative RA; Tb.1/N.SD, inhomogeneity of network; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; µFEA, micro-finite element analysis.

Figure 1.

Comparison of bone strength parameters between healthy controls, patients with anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-negative (RA−) and ACPA-positive (RA+) rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and impact of disease duration. Axial stiffness (upper row) and failure load (bottom row) are shown as mean±SD. Comparison between healthy controls (HC, white bars) and RA (RA−, grey/striped bars; RA+, black bars) are shown in A and F; between healthy men and men with RA in B and G; between healthy women and RA in C and H. Mean±SD values of three different RA+ disease duration subgroups are depicted in column D and H; for RA− in E and J.

Figure 2.

Depiction of a finite element analysis-derived stress distribution image of a healthy control (HC) and anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-negative (RA−) and ACPA-positive (RA+) rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Right and middle column display the right radius of a female patient with RA+ and RA−. Left column shows a gender-comparable and age-comparable HC. For comparison, full µFEA models (bottom) and cut through the radial bone (top) are shown to reveal differences in stress distribution for cortical and trabecular network. Colour map labels the von Mises stress (MPa) for described loading scenario.

Volumetric bone mineral density and bone microstructure are reduced in patients with RA+

We next compared structural bone parameters between the groups. Total, trabecular and cortical bone mineral densities (vBMD in mg HA/cm³) were decreased in patients with RA+ compared with HC (total vBMD: 256±58 vs 289±56, P<0.001; trabecular vBMD: 130±47 vs 164±37, P<0.001; cortical vBMD: 750±104 vs 786±656, P=0.021) with statistical significance. Microstructure analysis revealed significantly lower trabecular number (1.8±0.4 vs 2.0±0.3 1/mm, P<0.001) and thickness (0.06±0.01 vs 0.07±0.01 mm, P=0.025) in RA+. In addition, also cortical thickness was lower in patients with RA+ than in HC (0.59±0.21 vs 0.67±0.18 mm, P=0.012). Bone structure in RA− was fundamentally different: First, cortical vBMD was even higher in RA− than in HC. In addition, while trabecular vBMD was decreased in RA− compared with HC, trabecular bone loss was less pronounced than in RA+. Finally, total vBMD in RA− was not reduced as compared with HC (table 2).

Correlation between bone strength and structure in RA

We hypothesised that bone strength is related to structure in patients with RA. Indeed, failure load in patients with RA+ (rs=0.65; rs=0.64), like in patients with RA− (rs=0.58; rs=0.74) and HC (rs=0.44, rs=0.62), was significantly (all P<0.001) correlated to total vBMD and trabecular vBMD, respectively. Stiffness of bone was also significantly (all P<0.001) related to total (RA+: rs=0.68, RA−: rs=0.62, HC: rs=0.47) and trabecular vBMD (RA+: rs=0.61 RA−: rs=0.75, HC: rs=0.63). Interestingly, however, only patients with RA showed a correlation between bone strength and cortical vBMD (RA+: rs=0.24, P=0.021; RA−: rs=0.28, P=0.009), while there was no significant correlation in HC.

Sex effects on bone strength in RA

We then characterised sex-dependent differences of bone strength in RA. Failure load (2331±584 vs 1563±492 n, P<0.001) and stiffness (48.0±13.5 vs 32.1±11.4 kN/mm, P<0.001) were significantly higher in men with RA+ than in women with RA+. Similar differences, although at an overall higher level, were also found in HC and RA− with men showing higher failure load and stiffness than women. Even more importantly, healthy men showed significantly stiffer (57.2±10.1 kN/mm; P=0.006) and stronger (2752±445 N; P=0.002) bones than men with RA+ (48.0±13.5 kN/mm and 2331±584 N), respectively (figure 1). Furthermore, also healthy women showed significantly stiffer (37.5±11.4 kN/mm; P=0.009) and stronger bones (1813±508 N; P=0.006) than women with RA+ (table 3). No such differences were found in RA−. Bone size (cross-sectional area) was not different between RA+ (340±56 mm2) and HC (326±86 mm2) but was related to sex in RA+ (men: 421±75 mm2 vs women: 310±87 mm2, P<0.001) and HC (men: 398±81 mm2 vs women: 279±50 mm2, P<0.001). Detailed information on density and microstructural parameters of HC and patients with RA and their relation to sex are listed in table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of bone strength and structure in male and female healthy controls and patients with rheumatoid arthritis

| Groups | HC (n=96) | RA+ (n=96) | RA− (n=84) | |||

| Male (n=38) | Female (n=58) | Male (n=26) | Female (n=70) | Male (n=22) | Female (n=62) | |

| µFEA | ||||||

| Stiffness, kN/mm | 57.2±10.1*† | 37.5±11.4† | 48.0±13.5* | 32.1±11.4‡ | 51.9±11.6* | 37.8±10.8 |

| Failure load, N | 2752±445*† | 1813±508† | 2331±584* | 1563±492‡ | 2502±517* | 1803±484 |

| Bone structure (HR-pQCT) | ||||||

| Volumetric bone mineral density | ||||||

| Dtotal, mg HA/cm³ | 301±52† | 282±57 | 259±50 | 255±61‡ | 288±56 | 286±63 |

| Dtrab, mg HA/cm³ | 185±28*† | 151±36† | 145±42 | 124±47‡ | 170±30* | 142±43 |

| Dmeta, mg HA/cm³ | 240±30*† | 211±37† | 212±3 | 191±46 | 227±25* | 200±43 |

| Dinn, mg HA/cm³ | 147±27*† | 109±38† | 116±4* | 291±43 | 131±16* | 102±44 |

| Dcomp, mg HA/cm³ | 767±51* | 799±71 | 734±91 | 756±108‡ | 776±77* | 827±62 |

| Meta/Inn, % | 1.66±0.17* | 2.15±0.7 | 2.17±1.3 | 2.32±0.93 | 1.86±0.47 | 2.14±0.70 |

| Bone microstructure | ||||||

| BV/TV, % | 0.15±0.02*† | 0.13±0.03 | 0.13±0.03* | 0.11±0.04 | 0.14±0.03* | 0.12±0.04 |

| Tb.N, 1/mm | 2.18±0.21* | 1.95±0.32† | 1.93±0.42* | 1.76±0.41 | 2.17±0.27* | 1.84±0.37 |

| Tb.Th, mm | 0.07±0.01* | 0.06±0.01 | 0.07±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 | 0.07±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 |

| Tb.Sp, mm | 0.39±0.04* | 0.47±0.13† | 0.49±0.18 | 0.55±0.24 | 0.40±0.06* | 0.52±0.23 |

| Tb.1/N.SD, mm | 0.16±0.03 | 0.20±0.08† | 0.27±0.22 | 0.29±0.25 | 0.18±0.06 | 0.25±0.17 |

| Ct.Th, mm | 0.70±0.17 | 0.64±0.18 | 0.61±0.21 | 0.58±0.21‡ | 0.70±0.23 | 0.69±0.18 |

Bonferroni-Holm adjustment: critical P values indicating significant results for all investigated parameters were as follows: P1=0.0056, P2=0.0063, P3=0.0071, P4=0.0083, P5=0.01, P6=0.0125, P7=0.0167, P8=0.025, P9=0.05.

*Significance between men vs women in the same group.

†Significance between HC vs RA+ of same sex.

‡Significance between RA+ vs RA− of same sex.

§Significance between HC vs RA− of same sex.

BV/TV, trabecular bone volume per tissue volume; Ct.Th, cortical thickness; Dcomp, compact (cortical) volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD); Dinn, inner trabecular vBMD; Dmeta, meta-trabecular vBMD; Dtotal, total vBMD; Dtrab, trabecular vBMD; HC, healthy controls; HR-pQCT, high-resolution peripheral CT; Meta/Inn, ratio of meta-to-inner density; RA+, anti-citrullinated protein autoantibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA); RA−, anti-citrullinated protein autoantibody-negative RA; Tb.1/N.SD, inhomogeneity of network; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; µFEA, micro-finite element analysis.

Impact of disease duration on bone strength

We next analysed whether bone strength in RA is associated with disease duration. We compared stiffness and failure load in three groups of patients with RA+ and RA− with different disease durations (≤2 years: n=24; >2−<6 years: n=18; ≥6 years: n=54). In patients with RA+, stiffness of bone significantly declined with disease duration from 43.4±10.6 kN/mm (≤2 years) to 33.2±13.4 kN/mm (>2−<6 years; P=0.001) and 34.4±14.5 kN/mm (≥6 years: P=0.003). Similarly, failure load of bone declined from 2065±443 N (≤2 years) to 1615±619 N (>2−<6 years; P=0.001) and 1693±652 N (≥6 years: P=0.003) (table 4, figure 1). No such decline of stiffness and failure load was found in RA− (table 4). Furthermore, age of patients with RA+ with ≤2 years in disease duration did not differ from the ones with >2 years in disease duration. In accordance with the decline of biomechanical properties, also the volumetric and microstructural characteristics of bone declined with disease duration. Hence, especially volumetric BMD and microstructural parameters of the trabecular bone continuously decreased the longer patients with RA+ had been afflicted by disease (table 4).

Table 4.

Impact of RA disease duration on bone strength and structure

| Disease duration | RA+ | RA− | ||||

| ≤2 years | >2–<6 years | ≥6 years | ≤2 years | >2–<6 years | ≥6 years | |

| N | 24 | 18 | 54 | 43 | 21 | 20 |

| Age, years | 49.2±14.4 | 54.6±11.6 | 56.3±10.8 | 49.7±12.6*† | 57.5±11.9 | 59.0±8.3 |

| Sex, n male/n female | 9/15 | 4/14 | 13/41 | 9/34 | 7/14 | 6/14 |

| µFEA | ||||||

| Stiffness, kN/mm | 43.4±10.6*† | 33.2±13.4 | 34.4±14.5 | 42.6±12.0 | 40.2±10.2 | 40.5±16.0 |

| Failure load, N | 2065±433*† | 1615±620 | 1693±652 | 2023±542 | 1935±475 | 1942±754 |

| Bone structure (HR-pQCT) | ||||||

| Volumetric bone mineral density | ||||||

| Dtotal, mg HA/cm³ | 283±55† | 251±60 | 246±57 | 292±56 | 284±53 | 276±79 |

| Dtrab, mg HA/cm³ | 165±40† | 133±42 | 113±42 | 152±37 | 155±30 | 139±58 |

| Dmeta, mg HA/cm³ | 223±35*† | 191±41 | 186±43 | 210±34 | 213±33 | 195±58 |

| Dinn, mg HA/cm³ | 129±36*† | 95±41 | 85±42 | 112±41 | 114±30 | 100±59 |

| Dcomp, mg HA/cm³ | 772±98 | 752±100 | 740±106 | 830±63 | 802±74 | 793±74 |

| Meta/Inn, % | 1.79±0.35*† | 2.25±0.79 | 2.50±1.21 | 2.04±0.51 | 1.95±0.41 | 2.24±1.07 |

| Bone microstructure | ||||||

| BV/TV, % | 0.14±0.03*† | 0.11±0.03 | 0.11±0.03 | 0.13±0.03 | 0.13±0.03 | 0.12±0.05 |

| Tb.N, 1/mm | 2.04±0.30*† | 1.70±0.48 | 1.74±0.41 | 1.96±0.24 | 2.01±0.30 | 1.75±0.58 |

| Tb.Th, mm | 0.07±0.01† | 0.07±0.01‡ | 0.06±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 |

| Tb.Sp, mm | 0.43±0.09*† | 0.57±0.20 | 0.57±0.27 | 0.45±0.07 | 0.44±0.08 | 0.61±0.40 |

| Tb.1/N.SD, mm | 0.19±0.06*† | 0.34±0.27 | 0.31±0.28 | 0.20±0.05 | 0.19±0.06 | 0.34±0.28 |

| Ct.Th, mm | 0.61±0.20 | 0.56±0.22 | 0.59±0.21 | 0.71±0.18 | 0.66±0.18 | 0.66±0.24 |

Bonferroni-Holm adjustment: critical P values indicating significant results for all investigated parameters were as follows: P1=0.0167, P2=0.025, P3=0.05.

*Significance between ≤2 years’ and >2–<6 years’ disease duration.

†Significance between ≤2 years’ and ≥6 years’ disease duration.

‡Significance between >2–<6 years’ and ≥6 years’ disease duration.

BV/TV, trabecular bone volume per tissue volume; Ct.Th, cortical thickness; Dcomp, compact (cortical) volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD); Dinn, inner trabecular vBMD; Dmeta, meta-trabecular vBMD; Dtotal, total vBMD; Dtrab, trabecular vBMD; HR-pQCT, high-resolution peripheral CT; Meta/Inn, ratio of meta-to-inner density; RA+, anti-citrullinated protein autoantibody positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA); RA−, anti-citrullinated protein autoantibody negative RA; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.1/N.SD, inhomogeneity of network; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; µFEA, micro-finite element analysis.

Lower bone strength in patients with RA+ with low-impact fractures

We hypothesised that bone strength in patients with RA is associated with prevalent fractures and particularly focused on low-impact fractures that occurred after the diagnosis of RA. Although the absolute number of patients with RA+ with fractures was limited (n=9), those patients had significantly lower bone stiffness (28.0±9.4 kN/mm; P=0.020) and failure load (1374±412 N; P=0.012) along with lower trabecular vBMD (99±33; P=0.012) compared with patients with RA+ without fractures (stiffness: 39.1±14.2 kN/mm; failure load: 1890±638 N; trabecular vBMD: 138±45) suggesting that poor biomechanical properties of bone are associated with fracture. In contrast, very few fractures (n=3) occurred in patients with RA− with no association to bone strength.

Factors determining bone strength in RA

In order to search for parameters that influence failure load in patients with RA, we calculated linear regression models with sex, age, BMI, disease duration, biological DMARD use and ACPA status as independent variables. The first model accounted for 31.9% of the variance of failure load. Sex (P<0.001), age (P=0.040) and ACPA status (P=0.007) were independently associated with failure load of bone in RA. We calculated a similar model for bone stiffness using the same independent variables. This model accounted for a similar amount of variance (28.3%), again showing sex (P<0.001), age (P=0.038) and ACPA status (P=0.007) to be negatively and independently associated with reduced biomechanical properties of bone in patients with RA.

Two further regression models of failure load and stiffness including the total sample accounted for 43.9% of the variance of failure load and 40.4% of the variance of stiffness. In both models, sex, age and RA+ versus HC (ie, ACPA positivity) were negatively associated with the dependent variables (all P≤0.006). All results of regression models are depicted in online supplementary table 1.

annrheumdis-2017-212404supp001.docx (35.9KB, docx)

Discussion

The vast majority of knowledge on systemic bone loss in RA comes from dual energy X-ray absorptiometry studies, which do not take into account potential changes of bone microstructure. More recent analyses supported the notion that RA is characterised by substantial impairment of bone microstructure suggesting that its biomechanical properties may indeed be significantly altered. Nonetheless, the biomechanical properties of bone in patients with RA have not been characterised. This study now clearly shows that failure load and stiffness of bone are significantly impaired in both female and male patients with RA.

We used µFEA to define the biomechanical properties of bone in RA, which is currently the most advanced method to define the functional qualities of bone. To date, µFEA has been largely applied in healthy individuals,21–29 where fracture risk association has been described,27–29 and small cohorts of various non-inflammatory diseases such as Turner syndrome,30 type 1 diabetes,31 male osteoporosis,32 idiopathic scoliosis,33 chronic obstructive lung disease34 and end-stage renal failure.35 In contrast, biomechanical properties of bone in inflammatory diseases, especially in RA, remained inadequately characterised. While one small study found reduced bone strength in patients with ankylosing spondylitis,36 another study performed in RA failed to show such changes.37 However, these latter data need to be seen with caution as they are based on a rather small number of patients, who were characterised by surprisingly high bone mass—potentially based on their ethnic background, which makes differentiation from controls challenging.38 Furthermore, the study lacked important disease characteristics of RA such as ACPA status, which is essential since ACPA have shown to play a causal role in RA-related bone loss by inducing osteoclast differentiation.5–7

In our study comprising more than 250 patients and controls, bone strength was significantly reduced in patients with RA+. Our analyses showed that only patients with RA+ but not patients with RA− had a lower failure load and stiffness underlining the concept that patients with RA+ are a distinct population with respect to genetic background, pathogenesis and clinical manifestation of the disease.1 The differences in bone strength between patients with RA+ and RA− are likely based on the previously shown functional properties of ACPA and RF in inducing osteoclast differentiation5 6 39 and provide solid clinical evidence that the bone composition and strength in patients with RA depends on the presence of autoantibodies. In accordance and reflecting our previous data total, trabecular and cortical volumetric bone mineral densities as well as microstructural parameters of bone were all reduced in patients with RA+.11 Importantly, the differences in bone strength between RA+ and HC groups were found in both women and men and were related to disease duration. Most strikingly, however, low failure load and stiffness in patients with RA+ were associated with higher prevalence of osteoporotic fractures. This latter finding suggests that measurement of bone strength identified patients with RA at risk for fragility fracture.

Total, trabecular and cortical volumetric bone density in patients with RA+ were lower than those previously described in ankylosing spondylitis,36 40 inflammatory bowel diseases,41 psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis42 or even osteogenesis imperfecta.43 Similarl compromised bone was only described in postmenopausal women with fractures16 28 44 and for men with pathological fractures.32 Notably, however, patients with RA+ in our study were approximately 20 years younger than the participants included in the aforementioned studies. Published normative data on radial bones from healthy individuals measured by HR-pQCT also show substantially higher bone densities for comparable ages.15 45 From these normative data, it appears that bone in patients with RA+ has adopted the properties that are characteristic for the bone of a healthy individual 20 years older.

In summary, this study shows that bone strength is significantly reduced in both female and male patients with RA+ and associated with the development of osteoporotic fractures. Reduced bone strength in patients with RA+ results from profound changes in bone volumetric density and microarchitecture resembling the structural features of bone of a healthy individual 20 years older.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Contributors: FS, DS, AK, AJH and JR collected the data. AK, GS, DS, FS, KE and A-ML analysed and interpreted the data. FS, DS, AK and GS prepared and revised the manuscript. AK, DS and GS designed the study.

Funding: This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SPP1468-IMMUNOBONE; CRC1181;CRC1181-A01), the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF; project METARTHROS), the Marie Curie project OSTEOIMMUNE, the TEAM project of the European Union and the IMI-funded project RTCure.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was conducted upon approval of the local ethics committee of the University Clinic of Erlangen and with the authorisation of the National Radiation Safety Agency (Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2205–19. 10.1056/NEJMra1004965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schett G, Gravallese E. Bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis: mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8:656–64. 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Staa TP, Geusens P, Bijlsma JW, et al. Clinical assessment of the long-term risk of fracture in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3104–12. 10.1002/art.22117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen B, Cheng G, Wang H, et al. Increased risk of vertebral fracture in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2016;95:e5262 10.1097/MD.0000000000005262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harre U, Georgess D, Bang H, et al. Induction of osteoclastogenesis and bone loss by human autoantibodies against citrullinated vimentin. J Clin Invest 2012;122:1791–802. 10.1172/JCI60975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krishnamurthy A, Joshua V, Haj Hensvold A, et al. Identification of a novel chemokine-dependent molecular mechanism underlying rheumatoid arthritis-associated autoantibody-mediated bone loss. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:721–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Engdahl C, Bang H, Dietel K, et al. Periarticular bone loss in arthritis is induced by autoantibodies against citrullinated vimentin. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32:1681–91. 10.1002/jbmr.3158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathsson L, Mullazehi M, Wick MC, et al. Antibodies against citrullinated vimentin in rheumatoid arthritis: higher sensitivity and extended prognostic value concerning future radiographic progression as compared with antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:36–45. 10.1002/art.23188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Gaalen FA, Linn-Rasker SP, van Venrooij WJ, et al. Autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides predict progression to rheumatoid arthritis in patients with undifferentiated arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:709–15. 10.1002/art.20044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bugatti S, Bogliolo L, Vitolo B, et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and high levels of rheumatoid factor are associated with systemic bone loss in patients with early untreated rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:226 10.1186/s13075-016-1116-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kocijan R, Finzel S, Englbrecht M, et al. Differences in bone structure between rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis patients relative to autoantibody positivity. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:2022–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pistoia W, van Rietbergen B, Lochmüller EM, et al. Estimation of distal radius failure load with micro-finite element analysis models based on three-dimensional peripheral quantitative computed tomography images. Bone 2002;30:842–8. 10.1016/S8756-3282(02)00736-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Macneil JA, Boyd SK. Bone strength at the distal radius can be estimated from high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography and the finite element method. Bone 2008;42:1203–13. 10.1016/j.bone.2008.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engelke K, van Rietbergen B, Zysset P. FEA to measure bone strength: a review. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab 2016;14:26–37. 10.1007/s12018-015-9201-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khosla S, Riggs BL, Atkinson EJ, et al. Effects of sex and age on bone microstructure at the ultradistal radius: a population-based noninvasive in vivo assessment. J Bone Miner Res 2006;21:124–31. 10.1359/JBMR.050916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boutroy S, Bouxsein ML, Munoz F, et al. In vivo assessment of trabecular bone microarchitecture by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:6508–15. 10.1210/jc.2005-1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buie HR, Campbell GM, Klinck RJ, et al. Automatic segmentation of cortical and trabecular compartments based on a dual threshold technique for in vivo micro-CT bone analysis. Bone 2007;41:505–15. 10.1016/j.bone.2007.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. MacNeil JA, Boyd SK. Load distribution and the predictive power of morphological indices in the distal radius and tibia by high resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography. Bone 2007;41:129–37. 10.1016/j.bone.2007.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simon D, Kleyer A, Stemmler F, et al. Age- and sex-dependent changes of intra-articular cortical and trabecular bone structure and the effects of rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32 10.1002/jbmr.3025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Rietbergen B, Weinans H, Huiskes R, et al. A new method to determine trabecular bone elastic properties and loading using micromechanical finite-element models. J Biomech 1995;28:69–81. 10.1016/0021-9290(95)80008-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shanbhogue VV, Brixen K, Hansen S. Age- and sex-related changes in bone microarchitecture and estimated strength: a three-year prospective study using HRpQCT. J Bone Miner Res 2016;31:1541–9. 10.1002/jbmr.2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vilayphiou N, Boutroy S, Sornay-Rendu E, et al. Age-related changes in bone strength from HR-pQCT derived microarchitectural parameters with an emphasis on the role of cortical porosity. Bone 2016;83:233–40. 10.1016/j.bone.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Macdonald HM, Nishiyama KK, Kang J, et al. Age-related patterns of trabecular and cortical bone loss differ between sexes and skeletal sites: a population-based HR-pQCT study. J Bone Miner Res 2011;26:50–62. 10.1002/jbmr.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dalzell N, Kaptoge S, Morris N, et al. Bone micro-architecture and determinants of strength in the radius and tibia: age-related changes in a population-based study of normal adults measured with high-resolution pQCT. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:1683–94. 10.1007/s00198-008-0833-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hansen S, Shanbhogue V, Folkestad L, et al. Bone microarchitecture and estimated strength in 499 adult Danish women and men: a cross-sectional, population-based high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomographic study on peak bone structure. Calcif Tissue Int 2014;94:269–81. 10.1007/s00223-013-9808-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Melton LJ, Riggs BL, van Lenthe GH, et al. Contribution of in vivo structural measurements and load/strength ratios to the determination of forearm fracture risk in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:1442–8. 10.1359/jbmr.070514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vilayphiou N, Boutroy S, Sornay-Rendu E, et al. Finite element analysis performed on radius and tibia HR-pQCT images and fragility fractures at all sites in postmenopausal women. Bone 2010;46:1030–7. 10.1016/j.bone.2009.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boutroy S, Van Rietbergen B, Sornay-Rendu E, et al. Finite element analysis based on in vivo HR-pQCT images of the distal radius is associated with wrist fracture in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:392–9. 10.1359/jbmr.071108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stein EM, Silva BC, Boutroy S, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism is associated with abnormal cortical and trabecular microstructure and reduced bone stiffness in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:1029–40. 10.1002/jbmr.1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hansen S, Brixen K, Gravholt CH. Compromised trabecular microarchitecture and lower finite element estimates of radius and tibia bone strength in adults with Turner syndrome: a cross-sectional study using high-resolution-pQCT. J Bone Miner Res 2012;27:1794–803. 10.1002/jbmr.1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shanbhogue VV, Hansen S, Frost M, et al. Bone geometry, volumetric density, microarchitecture, and estimated bone strength assessed by HR-pQCT in adult patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Bone Miner Res 2015;30:2188–99. 10.1002/jbmr.2573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vilayphiou N, Boutroy S, Szulc P, et al. Finite element analysis performed on radius and tibia HR-pQCT images and fragility fractures at all sites in men. J Bone Miner Res 2011;26:965–73. 10.1002/jbmr.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cheuk KY, Zhu TY, Yu FW, et al. Abnormal bone mechanical and structural properties in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a study with finite element analysis and structural model index. Calcif Tissue Int 2015;97:343–52. 10.1007/s00223-015-0025-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Romme EA, Rutten EP, Geusens P, et al. Bone stiffness and failure load are related with clinical parameters in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:2186–93. 10.1002/jbmr.1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trombetti A, Stoermann C, Chevalley T, et al. Alterations of bone microstructure and strength in end-stage renal failure. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:1721–32. 10.1007/s00198-012-2133-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nigil Haroon N, Szabo E, Raboud JM, et al. Alterations of bone mineral density, bone microarchitecture and strength in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a cross-sectional study using high-resolution peripheral quantitative computerized tomography and finite element analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:377 10.1186/s13075-015-0873-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu TY, Griffith JF, Qin L, et al. Structure and strength of the distal radius in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a case–control study. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:794–806. 10.1002/jbmr.1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Popp KL, Hughes JM, Martinez-Betancourt A, et al. Bone mass, microarchitecture and strength are influenced by race/ethnicity in young adult men and women. Bone 2017;103:200–8. 10.1016/j.bone.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Harre U, Lang SC, Pfeifle R, et al. Glycosylation of immunoglobulin G determines osteoclast differentiation and bone loss. Nat Commun 2015;6:6651 10.1038/ncomms7651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klingberg E, Lorentzon M, Göthlin J, et al. Bone microarchitecture in ankylosing spondylitis and the association with bone mineral density, fractures, and syndesmophytes. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:R179 10.1186/ar4368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haschka J, Hirschmann S, Kleyer A, et al. High-resolution quantitative computed tomography demonstrates structural defects in cortical and trabecular bone in IBD patients. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:532–40. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kocijan R, Englbrecht M, Haschka J, et al. Quantitative and qualitative changes of bone in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis patients. J Bone Miner Res 2015;30:1775–83. 10.1002/jbmr.2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kocijan R, Muschitz C, Haschka J, et al. Bone structure assessed by HR-pQCT, TBS and DXL in adult patients with different types of osteogenesis imperfecta. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:2431–40. 10.1007/s00198-015-3156-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sornay-Rendu E, Boutroy S, Munoz F, et al. Alterations of cortical and trabecular architecture are associated with fractures in postmenopausal women, partially independent of decreased BMD measured by DXA: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:425–33. 10.1359/jbmr.061206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Burt LA, Liang Z, Sajobi TT, et al. Sex- and site-specific normative data curves for HR-pQCT. J Bone Miner Res 2016;31:2041–7. 10.1002/jbmr.2873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2017-212404supp001.docx (35.9KB, docx)