Abstract

p-Cresol, found at high concentrations in the serum of chronic kidney failure patients, is known to cause cell senescence and other complications in different parts of the body. p-Cresol is thought to mediate cytotoxic effects through the induction of autophagy response. However, toxic effects of p-cresol on mesenchymal stem cells have not been elucidated. Thus, we aimed to investigate whether p-cresol induces senescence of mesenchymal stem cells, and whether melatonin can ameliorate abnormal autophagy response caused by p-cresol. We found that p-cresol concentration-dependently reduced proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells. Pretreatment with melatonin prevented pro-senescence effects of p-cresol on mesenchymal stem cells. We found that by inducing phosphorylation of Akt and activating the Akt signaling pathway, melatonin enhanced catalase activity and thereby inhibited the accumulation of reactive oxygen species induced by p-cresol in mesenchymal stem cells, ultimately preventing abnormal activation of autophagy. Furthermore, preincubation with melatonin counteracted other pro-senescence changes caused by p-cresol, such as the increase in total 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase expression and decrease in the level of phosphorylated mechanistic target of rapamycin. Ultimately, we discovered that melatonin restored the expression of senescence marker protein 30, which is normally suppressed because of the induction of the autophagy pathway in chronic kidney failure patients by p-cresol. Our findings suggest that stem cell senescence in patients with chronic kidney failure could be potentially rescued by the administration of melatonin, which grants this hormone a novel therapeutic role.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, p-Cresol, Melatonin, Senescence, Autophagy

INTRODUCTION

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) experience a progressive loss of kidney function over a period of months or years. Consequently, the diseased kidneys fail to metabolize and excrete toxic metabolites and organic waste solutes, which are normally removed by healthy kidneys. It is known that such retained toxic products, commonly referred to as “uremic toxins,” are transported by the blood to other organs, causing adverse effects throughout the body (D’Hooge et al., 2003; Meijers et al., 2010). In fact, toxic metabolites or organic solutes accumulated owing to CKD are known to be directly responsible for various complications, such as cardiovascular disease, anemia, pericarditis, renal osteodystrophy, and neurological disorders (Meijers et al., 2010; Gabriele et al., 2016). To date, more than 100 different types of uremic toxins have been found. These uremic toxins can be divided into two major categories: 1) free, water-soluble substances that reversibly bind serum proteins and can be removed by dialysis; and 2) protein-bound solutes and peptides that are difficult to remove by conventional dialysis, so they can stay in the body for a long period of time (Neirynck et al., 2013). p-Cresol (PC) belongs to the second type of uremic toxins, as it binds to proteins. PC is frequently detected in the serum of CKD patients (Faure et al., 2006). PC induces cell senescence, apoptosis and immunodeficiencies in the cardiovascular system, brain, and kidneys of affected patients (Azevedo et al., 2016). However, effects of PC on adult stem cells in patients with CKD have not yet been elucidated.

When cells age or become damaged by external stimuli, they are replaced by new cells that differentiate from adult stem cells into corresponding tissue-specific cell types to maintain tissue stability (Krause et al., 2001). Such adult stem cells are divided into various types: hematopoietic stem cells (Till and Mc, 1961), mesenchymal stem cells (Phinney and Prockop, 2007), and neural stem cells (Altman and Das, 1965). Among them, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have a special self-renewal capacity with the potential to differentiate into multiple cell types, including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes, in multiple organs (Yun et al., 2009). MSCs are distributed all over the body, including bone marrow, cord blood, and adipose tissue; they are also present in large numbers in the bloodstream (Qiao et al., 2008). Owing to their ubiquitous nature, MSCs are easily exposed to uremic toxins that circulate in the blood of CKD patients. As a result, they may be vulnerable to toxin effects that can potentially complicate tissue regeneration process. Thus, it is important to evaluate possible harmful effects of uremic toxins, such as PC, on MSCs and find a way of controlling uremic toxin-induced MSC senescence.

Individuals with CKD experience disturbances of sleep, which may be linked to impaired endogenous melatonin secretion during nighttime (Maung et al., 2016). In light of known tissue regeneration problems in CKD patients, it is of interest to note that high blood melatonin levels may alleviate tissue regeneration disorders and other complications caused by CKD (Maung et al., 2016). Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxy tryptamine), secreted by the pineal gland, is a hormone that regulates sleep and wakefulness (Hardeland et al., 2006). Recently, melatonin has been used clinically, and it is available off the counter as a sleeping aid that has a strong action and few side effects. The vast potential of melatonin as a therapeutic agent is explained by its ubiquitous nature. Melatonin acts not only on the brain, but also on various locations in the whole body, such as pineal gland, reproductive organs, skin, lymphocytes, and gastrointestinal tract (Acuna-Castroviejo et al., 2014). Specifically, melatonin is known to have many beneficial effects on the body, as it improves motility, induces proliferation of MSCs, and increases the therapeutic effect of MSC transplantation (Lee et al., 2014). Thus, in our study, we sought to investigate possible effects of PC on MSCs, and consequently evaluate the potential of melatonin as a therapeutic agent with protective properties against PC-induced stem cell senescence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Human adipose tissue-derived MSCs were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). MSCs were confirmed to be pathogen- and mycoplasma-free. MSCs expressed specific cell surface markers [cluster of differentiation (CD) 73 and CD105, but not CD31]. MSCs were cultured in α-minimum essential medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. MSC cultures were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Cell proliferation assay

MSCs were exposed to PC (0, 50, 100, 500 μM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 72 h or PC (500 μM; for 72 h) with preincubation melatonin (0, 1, 10, 100 μM; for 30 min; Sigma-Aldrich) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; vehicle). Cell proliferation parameters were assessed using a cell proliferation 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) ELISA colorimetric kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). To perform ELISA, 100 μg/mL BrdU was added to cultured MSCs and incubated at 37°C for 6 h. Then, 1 M H2SO4 was added to stop the reaction. Light absorbance of the samples was measured by an ELISA reader (BMG labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) at 450 nm.

Beta-galactosidase staining assay

Senescence was assessed by measuring the percentage of cultured cells that stained positively for senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity as described previously (Cong et al., 2006). Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice and fixed with 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich). Fixed cells were incubated at 37°C (without CO2) for 12 h with a β-gal staining solution (1 mg/mL X-Gal, 40 mM citric acid-sodium phosphate buffer, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, and 5 mM potassium ferricyanide; pH 6.0; Sigma-Aldrich). Stained (blue, positive) and non-stained (negative) cells were counted by using phase contrast microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) in five independent cultures.

Catalase activity assay

MSCs were harvested from the culture dish by scraping with a rubber policeman on ice. To measure catalase activity, cell lysate protein extracts (40 μg) were incubated with 20 mM H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. Then, 50 mM Amplex Red reagent (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 0.2 U/mL of horseradish peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and incub ated for 30 min at 37°C. Changes in absorbance values associated with H2O2 degradation were measured by an ELISA reader (BMG labtech) at 563 nm.

Western blot assay

MSCs homogenates were extracted by using RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific). Cell lysates (20 μg of total protein) were separated by using 6–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Thermo Scientific). After the blots had been washed with a solution comprising 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6; Sigma-Aldrich), 150 mM NaCl (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich), the membranes were incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature and then, incubated with appropriate primary antibodies against phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), phosphorylated PI3K (p-PI3K), Akt, phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), phosphorylated 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), phosphorylated mTOR (p-mTOR), LC3, beclin 1, ATG7, p62/Sequestosome 1 (p62/SQSTM1), senescence marker protein 30 (SMP30), and β-actin (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). The membranes were then washed more than twice, and the primary antibodies were detected using a goat anti-rabbit IgG or a goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK).

Dihydroethidium staining

To measure superoxide anion levels in cultured MSCs, the cells were incubated with 10 μM dihydroethidium (DHE; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C. After washing with PBS three times, samples were visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) or analyzed by flow cytometry (Cyflow Cube 8 FACS; Sysmex Partec, Görlitz, Germany). Data were analyzed using standard FSC Express software (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Results of all experiments were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Comparisons of more than three groups were made by using the Bonferroni-Dunn test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant if p<0.05.

RESULTS

Melatonin prevents the reduction in MSC proliferation rate and MSC senescence induced by PC

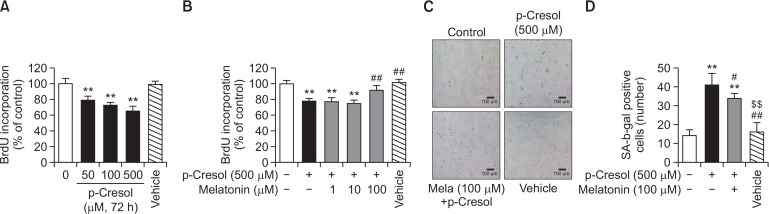

Exposure of MSCs to a range of PC concentrations (0–500 μM) for 72 h induced cell senescence as was indicated by decreased BrdU incorporation levels (Fig. 1A). At 500 μM PC, the lowest BrdU incorporation in MSCs was observed (Fig. 1A). It has been shown previously that treatment with 500 μM PC increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and inhibited cell viability, proliferation, and migration (Chang et al., 2014). To investigate the protective effect of melatonin, MSCs were pretreated with 0–100 μM melatonin before the exposure to PC for 72 h. We found that pretreatment with 100 μM melatonin reversed PC-induced decrease in BrdU incorporation (Fig. 1B), whereas incubation with lower concentrations of melatonin (1 and 10 μM) was without effect. Thus, 500 μM PC and 100 μM melatonin were used in the rest of the experiments to maximize the characteristic effects of these substances. To determine the effect of melatonin on cell senescence conferred by PC, cytochemical detection of SA-β-gal activity was performed. Melatonin was found to decrease PC-induced SA β-gal activity (Fig. 1C, 1D). These results support the notion that melatonin can counteract the reduction of MSC proliferation and induction of cell senescence caused by PC.

Fig. 1.

Effect of melatonin on p-cresol-induced cell senescence. (A) Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were exposed to 0–500 μM p-cresol (PC) or PBS (Vehicle) for 72 h, and 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation was measured by absorbance detection. The values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs). (B) MSCs were cultured in the absence of modulators or were exposed to 500 μM PC for 72 h with or without pretreatment with 1–100 μM melatonin, or PBS (Vehicle), and BrdU incorporation was measured by absorbance detection. The values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs); ##p<0.01 vs. PC alone. (C) A representative image of senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity staining is illustrated. Scale bar=100 μm. (D) Numbers of SA-β-gal-positive cells in different treatment groups are illustrated. The number of SA-β-gal-positive cells was significantly lower in PC-treated MSCs exposed to melatonin than in MSCs treated with PC only. The values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. Analysis of variance followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs); ##p<0.01 vs. PC alone, $$p<0.01 vs. melatonin+PC.

Melatonin inhibits PC-induced reactive oxygen species generation via PI3K/Akt-dependent catalase activation

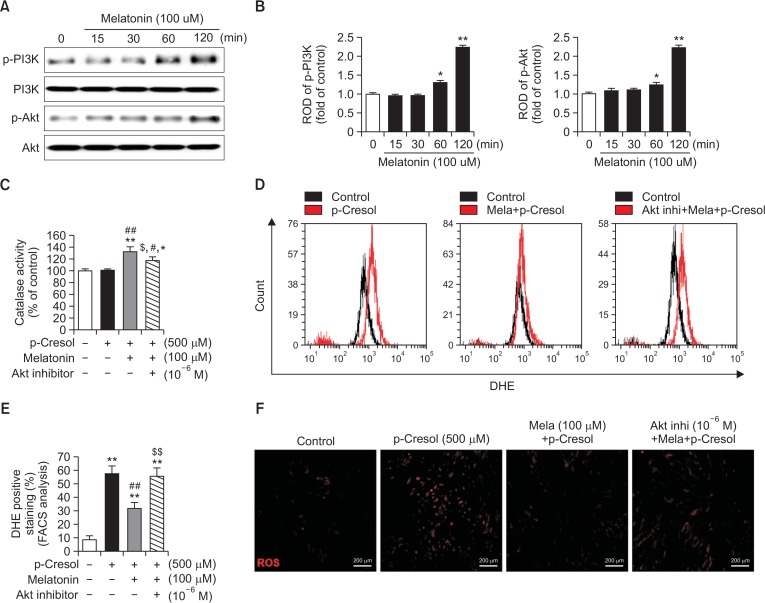

The cytoprotective effect of melatonin is thought to be mediated via its binding to melatonin receptors and subsequent activation of various signaling pathways that promote cell survival (Lee et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2017). Thus, we sought to specifically examine whether melatonin affected PI3K/Akt-dependent catalase activity and inhibited ROS generation. As shown in Fig. 2A and 2B, melatonin time-dependently increased levels of phosphorylated PI3K and Akt. Based on these results, we hypothesized that activation of the Akt signal transduction pathway by melatonin could affect catalase activity and ROS generation. Indeed, melatonin increased catalase activity, and this effect was sensitive to an Akt inhibitor (Fig. 2C). Next, to establish whether melatonin could suppress ROS generation induced by PC, we incubated MSCs with DHE, a widely used small-molecule fluorescent probe specific for O2− (Zhao et al., 2003). The reaction between O2− and DHE generates 2-hydroxyethidium, a highly specific red fluorescent product, that shifts excitation and emission peaks from 350 and 400 to 518 and 605 nm, respectively (Zielonka et al., 2008). MSCs were pretreated with melatonin in the presence or absence of an Akt inhibitor for 2 h and then exposed to PC for 12 h. Changes in DHE fluorescence excitation and emission peak intensities were quantified by using confocal microscopy and flow cytometry. We found that incubation with PC increased DHE intensity and the number of DHE-positive cells. These changes were inhibited by melatonin (Fig. 2D–2F). These results suggest that melatonin reduced PC-induced ROS generation through increased catalase activity via Akt pathway activation.

Fig. 2.

Protective effect of melatonin on p-cresol-induced changes in phospho-PI3K and phospho-Akt, and reactive oxygen species generation via Akt pathway-dependent catalase activation. (A) Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were treated with 100 μM melatonin for 0–120 min. At 120 min post melatonin, total protein extracts were prepared and immunoblotted with primary antibodies to phospho-PI3K and phospho-Akt. For normalization of band intensities, total PI3K and total Akt amounts were used as internal loading control. (B) Mean normalized levels of phospho-PI3K and phospho-Akt in the indicated samples are illustrated. The values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs). (C) MSCs were pretreated with 1 μM Akt inhibitor for 2 h before melatonin treatment. After pretreatment with the Akt inhibitor, MSCs were exposed to 100 μM melatonin for 2 h, and then, incubated for 72 h with p-cresol (PC). Next, catalase activity assays were carried out. Catalase activity values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. ANOVA followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs); #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. PC alone; $p<0.05 vs. melatonin+PC. (D) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was measured by using dihydroethidium (DHE) staining and flow cytometry. (E) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of DHE-positive cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. ANOVA followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs); ##p<0.01 vs. PC alone; $$p<0.05 vs. melatonin+PC. (F) Representative images of DHE fluorescence staining that indicated amounts of generated ROS in different treatment groups. Scale bar=200 μm.

Involvement of AMPK/mTOR pathway in the protective effect of melatonin

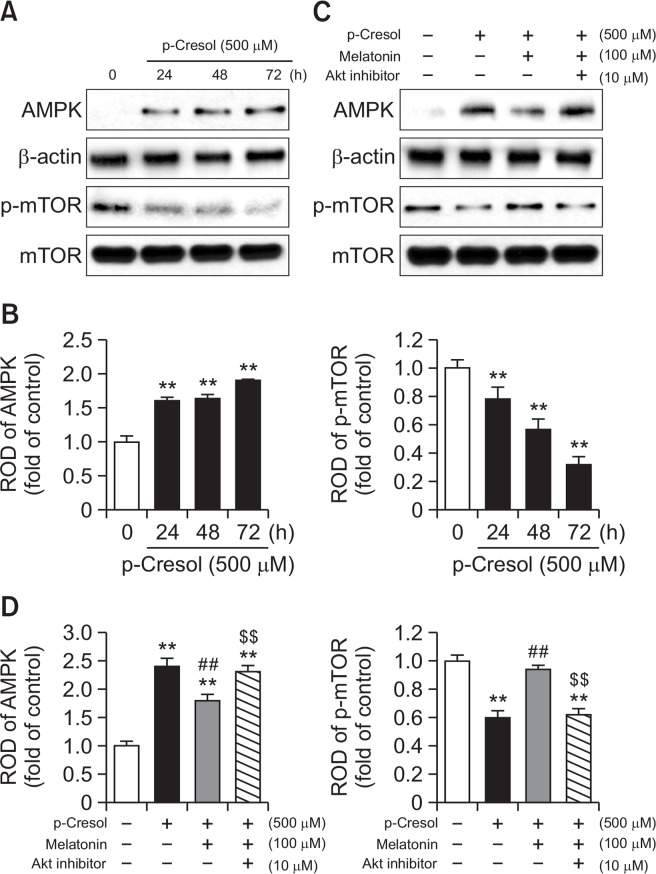

The increase in ROS is closely related to the activity of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Li et al., 2015). AMPK regulates various cellular processes, such as cell growth, apoptosis, and autophagy by modulating mTOR activity (Li et al., 2015). To investigate the involvement of AMPK and mTOR in melatonin-induced cytoprotective effect, we determined changes in AMPK expression and phosphorylation of mTOR induced by the exposure to PC or combined incubation of PC with melatonin. We observed that 500 μM PC increased total AMPK expression (Fig. 3A, 3B), but decreased mTOR phosphorylation (Fig. 3A, 3B) in MSCs in a time-dependent manner. Melatonin completely reversed these effects of PC, whereas pretreatment with an Akt inhibitor, in turn, counteracted the changes caused by melatonin (Fig. 3C, 3D). These results suggest that the protective effect of melatonin on PC-induced MSC senescence is mediated by AMPK and mTOR signaling pathways.

Fig. 3.

Effect of melatonin on p-cresol-induced AMPK expression and reduction of mTOR phosphorylation. (A) Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were treated with 500 μM p-cresol (PC) for 0–72 h. At 72 h after treatment with PC, total protein was extracted and immunoblotted with primary antibodies against total AMPK and phosphorylated mTOR. For normalization of band intensities, β-actin and total mTOR were used as internal loading control. (B) Mean normalized levels of AMPK and phospho-mTOR in the samples shown in (A) are illustrated. The values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs). (C) MSCs were pretreated with 1 μM Akt inhibitor for 2 h before the treatment with 500 μM for 2 h, and then incubated for 72 h with PC. Total protein extracts were then prepared and immunoblotted with primary antibodies against total AMPK and phosphorylated mTOR. For normalization of band intensities, β-actin and total mTOR were used as internal loading control. (D) Mean normalized levels of AMPK and phospho-mTOR levels in the samples shown in (C) are illustrated. The values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. ANOVA followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs); ##p<0.01 vs. PC alone; $$p<0.05 vs. melatonin+PC.

Melatonin inhibits PC-induced autophagy via Akt signaling

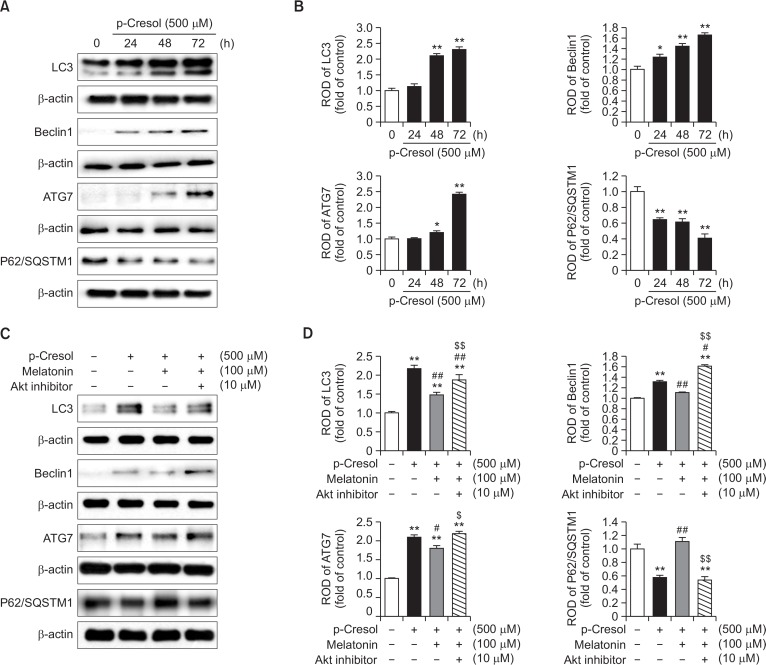

Excessive autophagy is associated with the inhibition of cell proliferation and increase in the number of senescent cells (Yang et al., 2011). To examine the effects of melatonin on PC-induced autophagy, we first determined how PC modulated the expression of autophagy-related proteins, such as LC3, beclin 1, ATG7, and p62/SQSTM1, which are key molecules in autophagosome formation. PC time-dependently increased the expression levels of LC3, beclin 1, and ATG7, but decreased the expression of p62/SQSTM1 (Fig. 4A, 4B). Correspondingly, pretreatment with melatonin counteracted PC-induced changes in LC3, beclin 1, and ATG7 expression levels, and restored p62/SQSTM1 expression reduced by PC (Fig. 4C, 4D). Finally, as in the experiments on the modulation of total AMPK and p-mTOR levels, co-application of an Akt inhibitor neutralized the effects of melatonin (Fig. 4C, 4D). Taken together, these results suggest that melatonin potentially affects expression levels of autophagy-related proteins via activation of the Akt pathway, ultimately preventing the induction of autophagy by PC.

Fig. 4.

Effect of melatonin on p-cresol-induced autophagy. (A) Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were treated with 500 μM p-cresol (PC) for 0–72 h. At 72 h after treatment with PC, total protein was extracted and immunoblotted with primary antibodies against LC3, beclin 1, ATG7, and p62/SQSTM1. For normalization of band intensities, β-actin was used as internal loading control. (B) Mean normalized levels of LC3, beclin 1, ATG7, and p62/SQSTM1 in the samples shown in (A) are illustrated. The values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs). (C) MSCs were pretreated with 1 μM Akt inhibitor for 2 h before the treatment with 500 μM melatonin for 2 h and then incubated for 72 h with PC. Total protein extracts were prepared and immunoblotted with primary antibodies against LC3, beclin 1, ATG7, and p62/SQSTM1. β-actin was used as an internal loading control. (D) Mean normalized levels of LC3, beclin 1, ATG7, and p62/SQSTM1 levels in the samples shown in (C) are illustrated. The values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. ANOVA followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs); #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. PC alone; $p<0.05 $$p<0.01 vs. melatonin+PC.

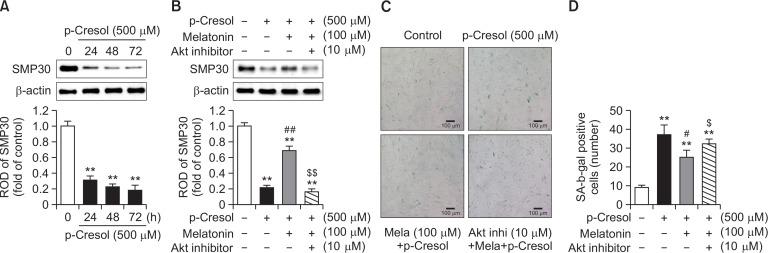

Protective effect of melatonin on PC-induced MSC senescence

Expression of senescence marker protein 30 (SMP30) decreases with age (Maruyama et al., 2010). In our experiments, PC decreased SMP30 expression in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 5A), which was in line with other senescence-related changes induced by PC. We found that pretreatment with melatonin rescued the reduction of SMP30 caused by PC, whereas protective effects of melatonin were, in turn, sensitive to the Akt inhibitor (Fig. 5B). As was shown above (Fig. 1C, 1D), melatonin prevented pro-senescence effects of PC. That effect of melatonin was also sensitive to the inhibition of the Akt pathway (Fig. 5C, 5D). These results suggest that melatonin diminished PC-induced reduction in the expression level of SMP30, which is involved in cell growth and anti-aging processes. This activity of melatonin was another manifestation of its potent restoring effects against PC-induced cell senescence.

Fig. 5.

Effect of melatonin on p-cresol-induced reduction of SMP30 expression. (A) Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were treated with 500 μM p-Cresol (PC) for 0–72 h. Upper panel − at 72 h after the treatment with PC, total protein extracts were prepared and immunoblotted with a primary antibody against SMP30. For normalization of band intensities, β-actin was used as internal loading control. Lower panel − mean normalized levels of SMP30 in samples shown in the upper panel are illustrated. The values are reported as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs). (B) MSCs were pretreated with 1 μM Akt inhibitor for 2 h before the treatment with 500 μM melatonin and subsequently incubated with PC for 72 h. Upper panel − total protein extracts were prepared and immunoblotted with an anti-SMP30 antibody. For normalization of band intensities, β-actin was used as internal loading control. Lower panel − mean normalized levels of SMP30 in the samples shown in the upper panel are illustrated. The values are reported as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. ANOVA followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs); ##p<0.01 vs. PC alone; $$p<0.01 vs. melatonin+PC. (C) A representative image of senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity staining. Scale bar = 100 μm. (D) Numbers of SA-β-gal-positive cells in different treatment groups are illustrated. The values are reported as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicate dishes. Analysis of variance followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test was used for multiple group comparisons: **p<0.01 vs. control (untreated MSCs); #p<0.05 vs. PC alone; $p<0.05 vs. melatonin+PC.

DISCUSSION

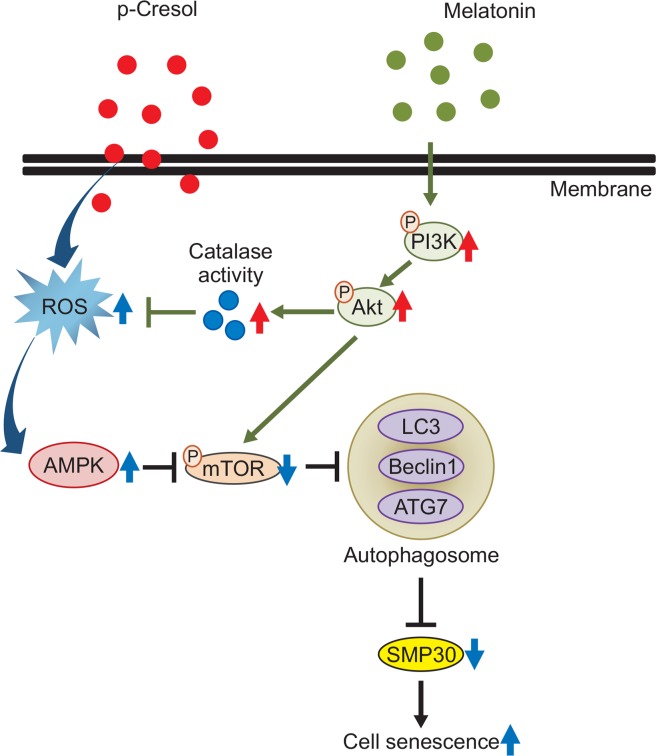

In our study, we for the first time demonstrated that the uremic toxin PC, found in individuals with CKD, caused MSC senescence. Furthermore, we demonstrated that pretreatment with melatonin prevented PC-induced senescence of MSCs by activating the PI3K and Akt pathways and by inhibiting ROS-dependent, AMPK pathway-mediated autophagy.

PC, a metabolite of environmental toxins, is a uremic toxic solute normally excreted by the kidneys. In conditions such as CKD, PC accumulates in the body (D’Hooge et al., 2003). In CKD, uremic toxins chronically stimulate renal endothelial cells. PC decreases the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules of endothelial cells and promotes monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells, thereby increasing endothelial monolayer permeability and inflammation (Dou et al., 2002; Cerini et al., 2004). Actual concentration of PC and the mechanism of its formation in several kidney diseases, including glomerulopathy, tubulointerstitial nephropathy, and acute kidney injury, still remain unclear. PC has been shown to activate caspase signaling and induce apoptosis and necrosis of renal epithelial tubular cells, producing a characteristic phenotype of CDK-related damage (Brocca et al., 2013). In addition, PC induces renal proximal tubular cell death by triggering autophagy and apoptosis (Lin et al., 2015). When not excreted properly, uremic toxic solutes adversely affect not only the kidneys, which are their primary target, but also other organs and systems (Meijers et al., 2010; Gabriele et al., 2016). Oxidative stress, DNA/mitochondrial damage, apoptosis, and the number of senescent cells were reported to increase in cardiomyocytes of mice with modeled cardiorenal syndrome in vivo (Chua et al., 2016). In addition, treatment of H9c2 cardiomyocyte cells with PC resulted in a decrease in mitochondrial ATP levels and enhanced senescence (Chua et al., 2016). With regard to physiological functions of stem cells, it has been shown that insulin promoted the differentiation of bone-marrow derived mouse MSCs into target cells in vivo by upregulating expression levels of HIF-1α, VEGF, and stromal cell-derived factor 1α via the PI3K/Akt-dependent pathway (Noh et al., 2014). PC has been previously shown to inhibit this signaling pathway and suppress mouse MSC differentiation (Noh et al., 2014). Thus, we initiated our study assuming that PC effect on mouse cells could be translated to a human model, so that normal physiological functions, such as proliferation and senescence, would be similarly affected in human MSCs. Indeed, our results showed that incubation with PC inhibited BrdU incorporation and increased the number of β-galactosidase-positive cells (Fig. 1), indicating inhibition of proliferation and induction of senescence. In an attempt to prevent MSC senescence induced by PC, we chose to pretreat MSCs with melatonin, which is an easily applied, inexpensively synthesized, natural protector with few side effects. Melatonin is an endogenous hormone secreted by the pineal gland (Hardeland et al., 2006). Its physiological blood concentrations are maintained within pM or low nM range (Reiter and Tan, 2003). In some tissues, melatonin is present at considerably higher concentrations because of tissue specificity (Reiter and Tan, 2003), and it has a precise concentration-dependent effect on stem cells. Specifically, it has been reported that at low concentrations, proliferation, differentiation, and survival of stem cells was increased by melatonin (Fu et al., 2011), whereas at higher melatonin concentrations, stem cell pluripotency became notably lower (Zhang et al., 2010). Because of this variable concentration-dependent effect on target cells, it was extremely important to find a precise concentration of melatonin that could prevent PC-induced senescence. In our study, we revealed that 100 μM melatonin restored MSC proliferation reduced by PC and partially counteracted the increase in the number of β-galactosidase positive cells, whereas at concentrations of 1 μM and 10 μM, melatonin did not have any significant effect (Fig. 1). Thus, we concluded 100 μM was the optimal concentration of melatonin for our experiments that sought to address possible signaling mechanisms of the protection against PC-induced MSC senescence.

Previous studies suggested that PC induced oxidative stress in CKD patients by activating catalase and NADPH oxidase (Watanabe et al., 2013; Chang et al., 2014), leading to cell cycle arrest and cytotoxicity. Melatonin, in turn, has been ascribed anti-oxidant properties and demonstrated to alleviate cell damage (Yu et al., 2017) via activation of pro-survival and proliferation-related signaling, such the Akt pathway (Mehrzadi et al., 2016). Consistent with these findings, we found that catalase activity and ROS generation were significantly increased in MSCs exposed to PC and that pretreatment with melatonin prevented these changes. In addition, pretreatment with an Akt inhibitor blocked melatonin rescuing effect against PC action, suggesting that melatonin-induced PI3K/Akt pathway activity is essential in the prevention of PC-induced catalase activation, ROS generation, and, ultimately, MSC senescence. Nevertheless, low concentrations of ROS are known to be effective for cell protection and intracellular debris elimination (Diehn et al., 2009; Park et al., 2016a). In addition, we found that melatonin counteracted increased expression of total AMPK and reduced phosphorylation of mTOR induced by PC (Fig. 3). As in the experiments that examined catalase activity, inhibition of Akt neutralized melatonin inhibitory effects on PC-induced changes in the expression of AMPK and phosphorylated mTOR (Fig. 3C, 3D). Consistent with our results, ROS-mediated AMPK up-regulation has been shown to inhibit mTOR phosphorylation, and to suppress stem cell differentiation and self-renewal (Adams et al., 2016; Riva et al., 2016). In addition, evidence suggests that the AMPK/mTOR signaling axis is important for autophagy-mediated cell senescence and aging (Michalik and Jarzyna, 2016; Ganesan et al., 2017). Despite that knowledge, PC has not been previously shown to modulate AMPK expression through the generation of ROS, and the possibility that this signaling can regulate mTOR phosphorylation has not been elucidated. Therefore, our results provide a new perspective on the mechanism of cell senescence induction by PC, implicating AMPK/mTOR signaling in this effect. Moreover, we showed that effects of PC on MSCs could be ameliorated by melatonin in an Akt pathway-dependent manner.

Next, we attempted to uncover consequences of mTOR dysregulation for other cellular responses that are important in cell senescence. PC has been shown to induce autophagy in human renal proximal tubular cells (Lin et al., 2015), whereas mTOR signaling is known to regulate autophagy during stem cell senescence and disease (Menendez et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2016; Maiese, 2016). However, whether PC can induce autophagy in MSCs and whether melatonin can prevent that effect, has not been clearly elucidated. It has been shown that PC could participate in autophagosome formation and regulate expression of autophagy-related proteins, such as ATG4, beclin 1, and LC3B-II, ultimately increasing autophagy response (Lin et al., 2015). In contrast, melatonin directly inhibited mTOR-dependent autophagy and ER stress-dependent autophagy, preventing autophagic cell death and senescence (Kang et al., 2014; Fernandez et al., 2015). In the present study, we observed that PC increased the expression levels of the autophagy marker proteins LC3, beclin-1, and ATG7 in MSCs, but decreased the expression of p62/SQSTM1. In addition, we found that preincubation with melatonin partially or completely restored changes in the expression of autophagy-related proteins altered by PC. Thus, it is plausible that protective effects of melatonin are partially mediated via the suppression of PC-induced autophagy. Furthermore, we found that pretreatment with an Akt inhibitor prevented the effect of melatonin, which highlighted the critical nature of Akt activation in downstream melatonin signaling. Melatonin has been previously characterized as an autophagy inhibitor that downregulates expression levels of autophagic proteins in myoblast and glioma cells (Kim et al., 2011, 2012; Martin et al., 2014). Therefore, we suggest that melatonin reduces autophagy and prevents MSC senescence induced by PC via activation of the Akt pathway. In support of this notion, we demonstrated that melatonin affected the expression of SMP30 (Fig. 5). SMP30 expression levels decrease with age and therefore, it is a critical marker of biological maturation and premature aging caused by pathological processes (Abbas et al., 2017; Lesniewski et al., 2017). In our experiments, PC-treated MSCs showed increased numbers of SA-β-gal-positive cells and lower levels of SMP30 expression (Fig. 5). Pretreatment with melatonin suppressed these changes, by decreasing the number of SA-β-gal-positive cells and increasing SMP30 levels (Fig. 5B-5D). Although our results do not directly provide a link between autophagy and SMP30 levels, a previous report showed that SMP30 expression was reduced by autophagy (Park et al., 2016b). Thus, our results strongly support the notion that melatonin-dependent activation of the Akt pathway counteracts PC-induced ROS/AMPK pathway-mediated autophagy and reduction in SMP30 expression, ultimately ameliorating MSC senescence caused by PC.

Overall, our experimental results highlight a considerable therapeutic potential of melatonin anti-autophagic effects that reverse PC-induced MSC senescence. By showing that the protective action of melatonin against PC-induced MSC senescence is sensitive to the incubation with an Akt inhibitor, we demonstrated key significance of the Akt signaling pathway activation in melatonin effects. Therefore, our findings reveal a novel role of melatonin and Akt pathway in autophagy and in MSC senescence associated with CKD. Although our study was performed in vitro, the results obtained suggest a way to rescue developing MSC senescence in patients with CKD. Further studies are required to examine the therapeutic effects of melatonin in detail by using a mouse model of CKD.

Fig. 6.

Hypothetical model for protection effect of melatonin in PC-induced MSC senescence. PC induced MSC senescence through ROS generation, which elicited the AMPK expression but decreased mTOR phosphorylation level. Subsequently, PC decreased SMP30 expression via upregulation of mTOR dependent autophagy. Melatonin blocked the autophagy activation through Akt mediated catalase activation and scavenging the PC-induced mTOR mediated autophagy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Research Foundation grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2016R1D-1A3B01007727, NRF-2017M3A9B4032528). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abbas M, Jesel L, Auger C, Amoura L, Messas N, Manin G, Rumig C, Leon-Gonzalez AJ, Ribeiro TP, Silva GC, Abou-Merhi R, Hamade E, Hecker M, Georg Y, Chakfe N, Ohlmann P, Schini-Kerth VB, Toti F, Morel O. Endothelial microparticles from acute coronary syndrome patients induce premature coronary artery endothelial cell aging and thrombogenicity: role of the Ang II/AT1 receptor/NADPH oxidase-mediated activation of MAPKs and PI3-kinase pathways. Circulation. 2017;135:280–296. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.017513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuna-Castroviejo D, Escames G, Venegas C, Diaz-Casado ME, Lima-Cabello E, Lopez LC, Rosales-Corral S, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Extrapineal melatonin: sources, regulation, and potential functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:2997–3025. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1579-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams WC, Chen YH, Kratchmarov R, Yen B, Nish SA, Lin WW, Rothman NJ, Luchsinger LL, Klein U, Busslinger M, Rathmell JC, Snoeck HW, Reiner SL. Anabolism-associated mitochondrial stasis driving lymphocyte differentiation over self-renewal. Cell Rep. 2016;17:3142–3152. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J Comp Neurol. 1965;124:319–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo ML, Bonan NB, Dias G, Brehm F, Steiner TM, Souza WM, Stinghen AE, Barreto FC, Elifio-Esposito S, Pecoits-Filho R, Moreno-Amaral AN. p- Cresyl sulfate affects the oxidative burst, phagocytosis process, and antigen presentation of monocyte-derived macrophages. Toxicol Lett. 2016;263:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocca A, Virzi GM, de Cal M, Cantaluppi V, Ronco C. Cytotoxic effects of p- cresol in renal epithelial tubular cells. Blood Purif. 2013;36:219–225. doi: 10.1159/000356370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerini C, Dou L, Anfosso F, Sabatier F, Moal V, Glorieux G, De Smet R, Vanholder R, Dignat-George F, Sampol J, Berland Y, Brunet P. P- cresol, a uremic retention solute, alters the endothelial barrier function in vitro. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:140–150. doi: 10.1160/TH03-07-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MC, Chang HH, Chan CP, Yeung SY, Hsien HC, Lin BR, Yeh CY, Tseng WY, Tseng SK, Jeng JH. p- Cresol affects reactive oxygen species generation, cell cycle arrest, cytotoxicity and inflammation/atherosclerosis-related modulators production in endothelial cells and mononuclear cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e114446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua S, Lee FY, Chiang HJ, Chen KH, Lu HI, Chen YT, Yang CC, Lin KC, Chen YL, Kao GS, Chen CH, Chang HW, Yip HK. The cardioprotective effect of melatonin and exendin-4 treatment in a rat model of cardiorenal syndrome. J Pineal Res. 2016;61:438–456. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hooge R, Van de Vijver G, Van Bogaert PP, Marescau B, Vanholder R, De Deyn PP. Involvement of voltage- and ligand-gated Ca2+ channels in the neuroexcitatory and synergistic effects of putative uremic neurotoxins. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1764–1775. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehn M, Cho RW, Lobo NA, Kalisky T, Dorie MJ, Kulp AN, Qian D, Lam JS, Ailles LE, Wong M, Joshua B, Kaplan MJ, Wapnir I, Dirbas FM, Somlo G, Garberoglio C, Paz B, Shen J, Lau SK, Quake SR, Brown JM, Weissman IL, Clarke MF. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:780–783. doi: 10.1038/nature07733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou L, Cerini C, Brunet P, Guilianelli C, Moal V, Grau G, De Smet R, Vanholder R, Sampol J, Berland Y. P- cresol, a uremic toxin, decreases endothelial cell response to inflammatory cytokines. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1999–2009. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.t01-1-00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure V, Dou L, Sabatier F, Cerini C, Sampol J, Berland Y, Brunet P, Dignat-George F. Elevation of circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with chronic renal failure. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:566–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A, Ordonez R, Reiter RJ, Gonzalez-Gallego J, Mauriz JL. Melatonin and endoplasmic reticulum stress: relation to autophagy and apoptosis. J Pineal Res. 2015;59:292–307. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Zhao SD, Liu HJ, Yuan QH, Liu SM, Zhang YM, Ling EA, Hao AJ. Melatonin promotes proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells subjected to hypoxia in vitro. J Pineal Res. 2011;51:104–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriele S, Sacco R, Altieri L, Neri C, Urbani A, Bravaccio C, Riccio MP, Iovene MR, Bombace F, De Magistris L, Persico AM. Slow intestinal transit contributes to elevate urinary p- cresol level in Italian autistic children. Autism Res. 2016;9:752–759. doi: 10.1002/aur.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan R, Hos NJ, Gutierrez S, Fischer J, Stepek JM, Daglidu E, Kronke M, Robinson N. Salmonella Typhimurium disrupts Sirt1/AMPK checkpoint control of mTOR to impair autophagy. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006227. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeland R, Pandi-Perumal SR, Cardinali DP. Melatonin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:313–316. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JW, Cho HI, Lee SM. Melatonin inhibits mTOR-dependent autophagy during liver ischemia/reperfusion. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;33:23–36. doi: 10.1159/000356647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Kim KH, Yoo YM. Melatonin protects against apoptotic and autophagic cell death in C2C12 murine myoblast cells. J Pineal Res. 2011;50:241–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Kim KH, Yoo YM. Melatonin-induced autophagy is associated with degradation of MyoD protein in C2C12 myoblast cells. J Pineal Res. 2012;53:289–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, Neutzel S, Sharkis SJ. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369–377. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Jung YH, Oh SY, Yun SP, Han HJ. Melatonin enhances the human mesenchymal stem cells motility via melatonin receptor 2 coupling with Gαq in skin wound healing. J Pineal Res. 2014;57:393–407. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesniewski LA, Seals DR, Walker AE, Henson GD, Blimline MW, Trott DW, Bosshardt GC, LaRocca TJ, Lawson BR, Zigler MC, Donato AJ. Dietary rapamycin supplementation reverses age-related vascular dysfunction and oxidative stress, while modulating nutrient-sensing, cell cycle, and senescence pathways. Aging Cell. 2017;16:17–26. doi: 10.1111/acel.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Saud SM, Young MR, Chen G, Hua B. Targeting AMPK for cancer prevention and treatment. Oncotarget. 2015;6:7365–7378. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q, Luo Z, Zeng J, Chen W, Foo SS, Lee SA, Ge J, Wang S, Goldman SA, Zlokovic BV, Zhao Z, Jung JU. Zika virus NS4A and NS4B proteins deregulate Akt-mTOR signaling in human fetal neural stem cells to inhibit neurogenesis and induce autophagy. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HH, Huang CC, Lin TY, Lin CY. p- Cresol mediates autophagic cell death in renal proximal tubular cells. Toxicol Lett. 2015;234:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiese K. Targeting molecules to medicine with mTOR, autophagy and neurodegenerative disorders. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:1245–1266. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin V, Sanchez-Sanchez AM, Puente-Moncada N, Gomez-Lobo M, Alvarez-Vega MA, Antolin I, Rodriguez C. Involvement of autophagy in melatonin-induced cytotoxicity in glioma-initiating cells. J Pineal Res. 2014;57:308–316. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama N, Ishigami A, Kondo Y. Pathophysiological significance of senescence marker protein-30. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2010;10 Suppl 1:S88–S98. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maung SC, El Sara A, Chapman C, Cohen D, Cukor D. Sleep disorders and chronic kidney disease. World J Nephrol. 2016;5:224–232. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v5.i3.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrzadi S, Safa M, Kamrava SK, Darabi R, Hayat P, Motevalian M. Protective mechanisms of melatonin against hydrogen peroxide induced toxicity in human bone-marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016 doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2016-0409. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijers BK, Claes K, Bammens B, de Loor H, Viaene L, Verbeke K, Kuypers D, Vanrenterghem Y, Evenepoel P. p- Cresol and cardiovascular risk in mild-to-moderate kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1182–1189. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07971109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez JA, Vellon L, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufi S, Vazquez-Martin A. mTOR-regulated senescence and autophagy during reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency: a roadmap from energy metabolism to stem cell renewal and aging. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3658–3677. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.21.18128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalik A, Jarzyna R. The key role of AMP- activated protein kinase (AMPK) in aging process. Postepy Biochem. 2016;62:459–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neirynck N, Vanholder R, Schepers E, Eloot S, Pletinck A, Glorieux G. An update on uremic toxins. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45:139–150. doi: 10.1007/s11255-012-0258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh H, Yu MR, Kim HJ, Jang EJ, Hwang ES, Jeon JS, Kwon SH, Han DC. Uremic toxin p- cresol induces Akt-pathway-selective insulin resistance in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:2443–2453. doi: 10.1002/stem.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Lee H, Lee HJ, Kim GC, Kim DY, Han S, Song K. Non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma efficiently promotes the proliferation of adipose tissue-derived stem cells by activating NO-response pathways. Sci Rep. 2016a;6:39298. doi: 10.1038/srep39298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Choi SH, Kim H, Ji ST, Jang WB, Kim JH, Baek SH, Kwon SM. Doxorubicin regulates autophagy signals via accumulation of cytosolic Ca2+ in human cardiac progenitor cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016b;17:E1680. doi: 10.3390/ijms17101680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney DG, Prockop DJ. Concise review: mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair--current views. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2896–2902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao C, Xu W, Zhu W, Hu J, Qian H, Yin Q, Jiang R, Yan Y, Mao F, Yang H, Wang X, Chen Y. Human mesenchymal stem cells isolated from the umbilical cord. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RJ, Tan DX. What constitutes a physiological concentration of melatonin? J Pineal Res. 2003;34:79–80. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2003.2e114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva B, De Dominici M, Gnemmi I, Mariani SA, Minassi A, Minieri V, Salomoni P, Canonico PL, Genazzani AA, Calabretta B, Condorelli F. Celecoxib inhibits proliferation and survival of chronic myelogeous leukemia (CML) cells via AMPK-dependent regulation of β-catenin and mTORC1/2. Oncotarget. 2016;7:81555–81570. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till JE, Mc CE. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res. 1961;14:213–222. doi: 10.2307/3570892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Miyamoto Y, Honda D, Tanaka H, Wu Q, Endo M, Noguchi T, Kadowaki D, Ishima Y, Kotani S, Nakajima M, Kataoka K, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Tanaka M, Fukagawa M, Otagiri M, Maruyama T. p- Cresyl sulfate causes renal tubular cell damage by inducing oxidative stress by activation of NADPH oxidase. Kidney Int. 2013;83:582–592. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZJ, Chee CE, Huang S, Sinicrope FA. The role of autophagy in cancer: therapeutic implications. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1533–1541. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Gong B, Duan W, Fan C, Zhang J, Li Z, Xue X, Xu Y, Meng D, Li B, Zhang M, Bin Z, Jin Z, Yu S, Yang Y, Wang H. Melatonin ameliorates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in type 1 diabetic rats by preserving mitochondrial function: role of AMPK-PGC-1α-SIRT3 signaling. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41337. doi: 10.1038/srep41337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun SP, Lee MY, Ryu JM, Song CH, Han HJ. Role of HIF-1alpha and VEGF in human mesenchymal stem cell proliferation by 17beta-estradiol: involvement of PKC, PI3K/Akt, and MAPKs. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C317–C326. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00415.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Su P, Xu C, Chen C, Liang A, Du K, Peng Y, Huang D. Melatonin inhibits adipogenesis and enhances osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells by suppressing PPARγ expression and enhancing Runx2 expression. J Pineal Res. 2010;49:364–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Kalivendi S, Zhang H, Joseph J, Nithipatikom K, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Superoxide reacts with hydroethidine but forms a fluorescent product that is distinctly different from ethidium: potential implications in intracellular fluorescence detection of superoxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1359–1368. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielonka J, Srinivasan S, Hardy M, Ouari O, Lopez M, Vasquez-Vivar J, Avadhani NG, Kalyanaraman B. Cytochrome c-mediated oxidation of hydroethidine and mito-hydroethidine in mitochondria: identification of homo- and heterodimers. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]