Abstract

Physical activity (PA) and cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) are associated with successful brain and cognitive aging. However, little is known about the effects of PA, CRF, and exercise on the brain in the oldest-old. Here we examined white matter (WM) integrity, measured as fractional anisotropy (FA) and WM hyperintensity (WMH) burden, and hippocampal volume of Olga Kotelko (1919–2014). Olga began training for competitions at age of 77 and as of June 2014 held over 30 world records in her age category in track-and-field. We found that Olga’s WMH burden was larger and the hippocampus was smaller than in the reference sample (58 healthy low-active women 60–78 years old), and her FA was consistently lower in the regions overlapping with WMH. Olga’s FA in many normal-appearing WM regions, however, did not differ or was greater than in the reference sample. In particular, FA in her genu corpus callosum was higher than any FA value observed in the reference sample. We speculate that her relatively high FA may be related to both successful aging and the beneficial effects of exercise in old age. In addition, Olga had lower scores on memory, reasoning and speed tasks than the younger reference sample, but outperformed typical adults of age 90–95 on speed and memory. Together, our findings open the possibility of old-age benefits of increasing PA on WM microstructure and cognition despite age-related increase in WMH burden and hippocampal shrinkage, and add to the still scarce neuroimaging data of the healthy oldest-old (> 90 years) adults.

Keywords: physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, white matter, diffusion tensor imaging, fractional anisotropy, white matter hyperintensities, leukoaraiosis, aging, maximum oxygen consumption, accelerometry, sedentary, sedentariness, genu corpus callosum, oldest-old, athlete, cognitive performance, speed, memory, fluid intelligence, hippocampus, volume, Freesurfer

Introduction

Participation in aerobic exercise and higher cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) have protective effects on brain structure and function, and may act against age-related cognitive decline (Hillman, Erickson, & Kramer, 2008). Disruption of axons and myelin in white matter (WM) is considered one of the primary mechanisms underlying typical age-related cognitive decline (Madden et al., 2012), and loss of hippocampal volume is predictive of cognitive decline in both non-demented and demented older adults (Lopez et al., 2014; Mungas et al., 2005). Therefore, maintaining healthy WM and hippocampal structure and function is key for maintaining cognitive and functional independence into old age.

Previous studies demonstrated that regular participation in exercise and greater CRF is related to lower volume of WM hyperintensities (WMH) and higher WM microstructural integrity in healthy non-athletic older adults (Burzynska et al., 2014; Gow et al., 2012; Johnson, Kim, Clasey, Bailey, & Gold, 2012), in highly fit older adults (Marks et al., 2007), as well as older Master’s athletes (Tseng et al., 2013). Greater CRF is associated with greater hippocampal volume (Erickson et al., 2009; Erickson, Gildengers, & Butters, 2013; Voss, Vivar, et al., 2013), and 1-year aerobic training increased hippocampal volume and memory in healthy older adults (Erickson et al., 2011). Still, it is unknown whether starting an exercise routine after the age of 75 can elicit positive effects on the brain.

There is some evidence that greater PA at 85 years and older is related to lower risk of dementia (S. Wang, Luo, Barnes, Sano, & Yaffe, 2013), reduction in mortality and survival benefit (Stessman, Hammerman-Rozenberg, Cohen, Ein-Mor, & Jacobs, 2009), while greater PA at 70 increases the chance of becoming a nonagenarian (Edjolo et al., 2013). Together, PA in old age can increase chances of longevity and a dementia-free life. Still, it is unknown about how PA, CRF, and exercise are associated with brain health in the oldest old (>85).

In this study, we compared the WM health, hippocampal volume, and cognitive performance of Olga Kotelko, a world-famous nonagenarian track-and-field athlete, to a sample of 58 low-active community-dwelling women of age 60–78 (reference sample). Olga started training for track-and-field not before age 77. At the time of her death in June 2014 she held over 30 world records in her age category for the Masters competition (90–95; http://world-masters-athletics.org/records/outdoor-women). By examining her brain we take a first step towards understanding the possible links between brain health and initiating an exercise regime in very old age.

We collected Olga’s neuroimaging data at age of 93, after 16 years of track-and-field exercise training, and over 20 years of her post-retirement increased PA. The mean age of the reference sample thus represents approximately the age when Olga started her above-average active lifestyle.

We considered alternative predictions about Olga’s brain health. Her advanced age should be related to high volume of WMH, smaller hippocampus and low microstructural integrity when compared to the reference sample, as WM microstructure and hippocampal volume decrease accelerates in late adulthood. Conversely, it could be possible that engaging in exercise from the age of 65 onwards decelerated the age-related changes in Olga’s brain, and there could be negligible differences in her WMH burden, hippocampal volume, and microstructural integrity compared to the younger reference sample of older women.

Methods

Olga Kotelko (1919–2014)

In Olga’s youth, her only athletic activity was playing pick-up baseball at school. When she retired as a schoolteacher in 1984 at age of 65, she returned to slow-pitch softball. At age 77, she started training for tract-and field competitions, and since 1980 she trained with a coach. The training sessions were intense, up to 3 times per week and 3-hours long, which she continued until her mid 80s. Since then, her training sessions were less intensive, but she had been doing Aquafit classes three times a week and trained more intensively before competition season. In 2010, at age 91, her performance far surpassed that of many competitors’ two age brackets younger. In addition, she engaged in many every day life activities ((Grierson, 2014); http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/28/magazine/28athletes-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0). Olga reported no diagnosis or symptoms of hypertension.

Reference sample

The participants were 58 community dwelling, non-exercise trained but healthy older females (age range 60–78, M=65.7±4.2 SD, years of education 12–26, M=16.5±3.2) recruited from the greater Champaign-Urbana area. Eligible participants met the following criteria: (1) were between the ages of 60 and 80 years old, (2) were free from psychiatric and neurological illness and had no history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, (3) scored 27 or higher on the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) and >21 on Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS-M) questionnaire, (4) scored < 10 on the geriatric depression scale (GDS-15), (5) were right-handed, (6) demonstrated normal or corrected-to-normal vision of at least 20/40 and no color blindness, and (7) were cleared for suitability in the MRI environment.

The Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Illinois approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants received financial reimbursement. All participants obtained individual physician’s approval to engage in CRF testing.

CRF assessment

The PA was quantified with accelerometry (Burzynska et al., 2014) and CRF was measured as peak oxygen consumption [VO2max, ml/kg/min] during a modified Balke graded maximal exercise test. Both PA and CRF measures defined them as low-active, low-fit, but otherwise healthy group, representative for their age. Two women with extremely high CRF values (> ±2.5 SD) were considered outliers and data of one participant was not recorded properly, resulting in a sample of 55 for CRF data. Olga’s CRF was measured at the Montreal Chest Institute, McGill University in Montreal, Canada, in 2010, using the same standard methods. One participant’s accelerometry data was not recorded correctly and therefore the sample size for accelerometry was 57.

MRI acquisition

All MRI images were acquired on a 3T Siemens Trio Tim system with 45 mT/m gradients and 200 T/m/sec slew rates (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Diffusion-weighted and T2-weighted images were obtained parallel to the anterior-posterior commissure plane with no interslice gap. T2-weighted images consisted of 35 (28 slices for Olga) 4-mm-thick slices with an in-plane resolution of 0.86 × 0.86 (256 × 256 matrix, TR/TE = 5950/63 ms, FA = 120).

Diffusion images were acquired with a twice-refocused spin echo single-shot Echo Planar Imaging sequence. The protocol consisted of a set of 30 non-collinear diffusion-weighted acquisitions with b-value = 1000s/mm2 and two T2-weighted b-value = 0 s/mm2 acquisitions, repeated two times (TR/TE = 5500/98 ms, 128 × 128 matrix, 1.7×1.7 mm2 in-plane resolution, flip angle = 90 degrees, GRAPPA acceleration factor 2, and bandwidth of 1698 Hz/Px, comprising 40 3-mm-thick slices). Olga’s diffusion data was acquired with a similar protocol that differed in the following parameters: TR/TE = 7300/97 ms, 1.875×1.875 mm2 in-plane resolution, 54 2-mm-thick slices).

Structural MR scans were acquired using a 3D MPRAGE T1-weighted sequence (TR = 1900 ms; TE = 2.32 ms; TI: 900 ms; flip angle = 9°; matrix = 256 × 256; FOV = 230mm; 192 slices; resolution = 0.9 × 0.9 × 0.9 mm; GRAPPA acceleration factor 2).

The raw images used in this study (MPRAGE, T2-WI, and DTI) are available at https://central.xnat.org under project ID “OlgaKotelko”, with the permission of Olga and her family.

DTI analysis

DTI allows inferences about WM microstructural integrity in vivo by quantifying the magnitude and directionality of diffusion of water within a tissue. Fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of the directional dependence of diffusion, reflects the level of WM integrity within a voxel (Beaulieu, 2002), in which higher FA serves as a proxy measure of faster and more reliable information transfer along axons.

Diffusion data were processed and FA maps were computed using the FSL Diffusion Toolbox (FDT) v.3.0 in a standard multistep procedure with default settings. Images were carefully inspected at each level of preprocessing, including visual inspection of each raw diffusion data volume by AZB.

We used Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (Smith et al., 2007) within FSL v5.0.1 with default settings, to create a representation of main WM tracts common to all subjects.

We averaged the FA values from all the main WM tracts for each participant to obtain global FA. In addition, for regional post-hoc analyses, we extracted FA values from 22 regions (Burzynska et al., 2013) representing core parts of main association, projection, and commissural fibers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fitness, FA, WMH, and hippocampal volume: Olga Kotelko and the 58 females.

| Variable | n | Mean±SD* | Range* | Olga’s value | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 | 65.7±4.2 | 60–78 | 93 | 49.7 | <.001 |

| CRF (mL/kg/min) *** | 55 | 19.6±4.2 | 12–31 | 16 | 5.7 | <.001 |

| Daily physical activity (min) | ||||||

| Sedentary | 57 | 524±77(8.7h) | 350–678(6–11h) | ca. 1 h | 45.7 | <.001 |

| Light | 57 | 277±66 (4.6h) | 140–451(2–8h) | ca. 12h+ | 50.9 | <.001 |

| Moderate | 57 | 14±13(0.2h) | 0.83–66(<1min–1h) | ca. 2h+ | 61.0 | <.001 |

| Vigorous | 57 | 0.9±4 | 0.00–24 (0–<0.5h) | ca. 1h+ | 112 | <.001 |

| WMH volume (voxels) | 58 | 681±1179 | 1–7290 | 16313 | 100.9 | <.001 |

| Fractional anisotropy (FA) | ||||||

| Global WM | 56 | .45±.02 | .42–.49 | .47 | 7.0 | <.001 |

| PFC | 56 | .42±.02 | .38–.46 | .45 | 11.8 | <.001 |

| Whole CC | 58 | .67±.03 | .58–.74 | .75 | 17.0 | <.001 |

| CC 1 | 58 | .70±.03 | .65–.76 | .77 | 21.3 | <.001 |

| CC 2 | 58 | .63±.04 | .52–.72 | .71 | 13.3 | <.001 |

| CC 3 | 58 | .63±.06 | .49–.74 | .62 | 2.0 | .053 |

| CC 3 | 58 | .60±.07 | .42–.73 | .58 | 1.8 | .082 |

| CC 5 | 58 | .81±.02 | .75–.86 | .83 | 6.2 | <.001 |

| ALIC | 58 | .55±.03 | .47–.61 | .56 | 1.5 | .152 |

| PLIC | 58 | .69±.03 | .65–.75 | .73 | 12.6 | <.001 |

| antCING | 58 | .46±.03 | .41–.53 | .46 | 1.1 | .278 |

| vCING | 56 | .50±.06 | .40–.64 | .57 | 9.1 | <.001 |

| EC | 58 | .42±.03 | .37–.48 | .41 | 2.4 | .018++ |

| FX | 58 | .36±.06 | .20–.47 | .31 | 6.4 | <.001 |

| CP | 56 | .69±.04 | .61–.81 | .72 | 5.5 | <.001 |

| fMIN | 58 | .41±.03 | .33–.46 | .40 | 1.6 | .126 |

| fMAJ | 56 | .61±.03 | .53–.67 | .57 | 11.3 | <.001 |

| SLF | 58 | .46±.03 | .41–.52 | .46 | 0.1 | .944 |

| mPFC | 58 | .39±.02 | .33–.45 | .40 | 3.2 | .002 |

| SCR | 58 | .56±.03 | .51–.61 | .48 | 24.1 | <.001 |

| MTL | 56 | .55±.03 | .49–.60 | .53 | 4.6 | <.001 |

| OCCIP | 56 | .57±.03 | .50–.67 | .46 | 25.3 | <.001 |

| UNC | 58 | .48±.03 | .41–.58 | .53 | 11.9 | <.001 |

| TEMP | 56 | 33±.03 | .27–.41 | .40 | 17.2 | <.001 |

| pfcUNC | 58 | .33±.02 | .28–.39 | .39 | 17.0 | <.001 |

| Hippocampus Volume cm3 | ||||||

| R HIPP | 57 | 4.13±.041 | 3.28–4.94 | 3.53 | 11.1 | <.001a |

| L HIPP | 57 | 4.01±.042 | 2.62–4.82 | 3.49 | 9.2 | <.001 a |

| ICV | 57 | 1391±108 | 1238–1718 | 1420 | 2.0 | .046 |

| R HIPP adj | 57 | 4.13±.033 | 3.40–4.74 | 3.47 | 15.2 | <.001 |

| L HIPP adj | 57 | 4.01±.034 | 2.75–4.71 | 3.43 | 12.7 | <.001 |

These are the best estimates we could get based on Olga’s self report and information we had from Bruce Grierson. Prefrontal WM (PFC), FA for the whole corpus callosum (whole CC), five regions of the corpus callosum (CC 1, 2, 3, 4, 5), anterior and posterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC and PLIC), anterior dorsal (antCING) and ventral cingulum (vCING), external capsule (EC), fornix (FX), cerebral peduncles (CP), forceps major (fMAJ), forceps minor (fMIN), superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), WM of medial PFC (mPFC), superior corona radiata (SCR), medial temporal lobe WM (MTL), posterior periventricular WM containing occipital portion of inferior longitudinal fasciculi and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculi (OCCIP), WM-containing uncinate and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculi (UNC), WM of the temporal pole related to inferior longitudinal fasciculus (TEMP), and ventral prefrontal part of uncinate (pfcUNC).

Not significant after Bonferroni correction. HIPP: hippocampus, L:left, R:right, ICV: intracranial volume. adj: HIPP volume values adjusted for the ICV.

White Matter Hyperintensity (WMH) volume

We estimated WMH volume using a semi-automated procedure described and validated earlier (Burzynska et al., 2009), where AZB performed the manual masking of WMH regions. The WMH volume was expressed as number of voxels.

Hippocampal (HIPP) volume

We employed automated brain tissue segmentation and reconstruction with default settings of Freesurfer version 5.3 to estimate bilateral hippocampal volumes. This method is known to have best overlap and correlations with the gold standard for the measurement of the hippocampal structures: manual tracing (Morey et al., 2009). AZB screened all registrations and subcortical segmentations to evaluate the success of the automatically processed results. The volume of each hippocampus was measured as mm3 and then converted to cm3. One participant did not have good quality MPRAGE data, resulting in n=57 for hippocampal volume of the reference sample.

As regional brain volumes are correlated with head size, we calculated the adjusted volume of hippocampus using the estimated intracranial volume (ICV). The adjusted volume (HIPP adj) = raw volume–b × (ICV–mean ICV), where b is the slope of a regression of an ROI volume on ICV (Erickson et al., 2009; Raz et al., 2004). We used the same function for all participants (reference sample and Olga). The mean ICV was 1392 cm3 and the unstandardized b was.002 for both the L HIPP and the R HIPP. As expected, after adjustment for the ICV, the HIPP volumes were no longer correlated with the ICV.

Cognitive assessment and analysis

We administered a cognitive battery as described in the Virginia Cognitive Aging Project (Salthouse & Ferrer-Caja, 2003) to obtain measures of fluid intelligence, perceptual speed, and episodic memory (Table 2). The computer-based tasks were programmed in E-prime version 1.1 (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA) and administered on computers with 17″ cathode ray tube monitors. Due to time constraints (all MRI and cognitive data was obtained on a single visit), Olga did not complete the full cognitive battery. We compared Olga’s performance to the references sample, as well as to a group of 48 adults of age 90–95.

Table 2.

Neuropsychological measures: Olga Kotelko, 58 females (age 60–78) and 48 nonagenarians (age 90–95).

| Variable | Olga |

|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 females age 60–78 | 48 adults age 90–95* | ||||||||

| n | Mean±SD | Range | t | p-value | Mean±SD | t | p-value | ||

| Perceptual Speed | |||||||||

| Digit-Symbol Substitution | 53 | 58 | 68.1±11.8 | 46–93 | 10.2 | <.001 | 39.80±12.66 | 7.2 | <.001 |

| Pattern Comparison | 30 | 58 | 32.6±5.9 | 22–46 | 3.3 | .002 | 9.66±3.19 | 44.2 | <.001 |

| Letter Comparison | 16 | 58 | 20.5±3.9 | 11–30 | 8.7 | <.001 | 5.94±1.92 | 36.3 | <.001 |

| Memory | |||||||||

| Paired Associates | 1 | 57 | 4.1±3.0 | 0–12 | 7.7 | <.001 | 0.78±1.00 | 1.5 | .134 |

| Word Recall | 34 | 58 | 43.3±10.4 | 0–63 | 6.8 | <.001 | 20.49±7.74 | 12.1 | <.001 |

| Logical memory | 37 | 57 | 44.3±9.0 | 27–60 | 6.1 | <.001 | 29.42±8.15 | 6.4 | <.001 |

| Fluid intelligence | |||||||||

| Form Board | 3 | 58 | 5.6±3.4 | 0–14 | 5.9 | <.001 | 2.57±1.87 | 1.6 | .086 |

| Letter Set | 12 | 57 | 11.6±2.5 | 2–15 | 1.3 | .193 | 6.25±2.81 | 14.2 | <.001 |

| Matrix | 5 | 58 | 8.6±2.9 | 2–14 | 9.4 | <.001 | 2.78 ±1.70 | 9.0 | <.001 |

| Paper Folding | 1 | 58 | 5.5±2.1 | 2–9 | 16.3 | <.001 | 3.0±1.79 | 7.7 | <.001 |

| Spatial Relations | 3 | 58 | 8.1±4.5 | 0–19 | 8.7 | <.001 | 4.02±2.33 | 3.0 | .004+ |

| Shipley | 10 | 58 | 13.2±3.4 | 2–19 | 7.3 | <.001 | 7.78 ±3.70 | 6.6 | <.001 |

After Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, this result was not significant.

Data is a courtesy of Tim Salthouse. All participants MMSE>25.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (v.16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). We used one sample t-test to compare Olga to the reference samples.

Results

Olga was significantly older and had lower CRF than the reference sample (Table 1). Olga’s current PA, based on her self-report, was much higher than the reference sample, while her level of sedentariness was significantly lower that the reference sample.

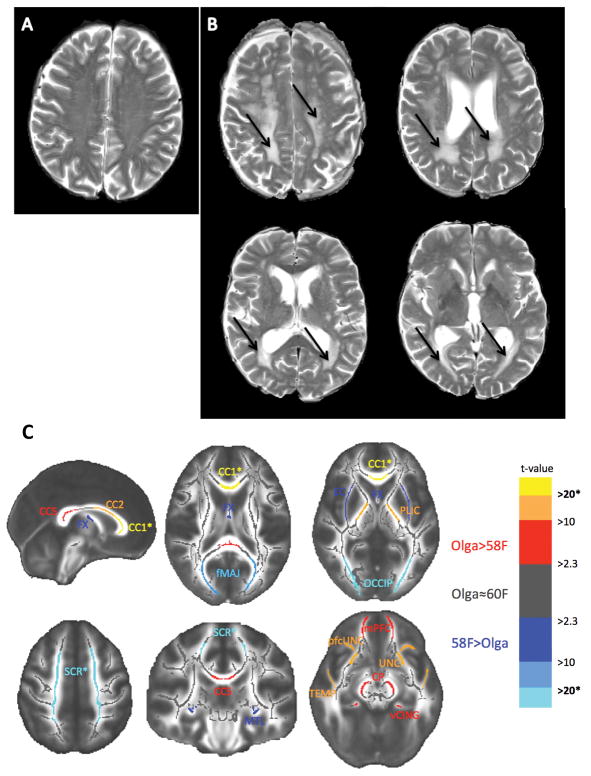

White matter

Olga Kotelko’s WMH volume was more than twice that of the person with largest WMH burden in the reference sample (Table 1). Figure 1- A shows Olga’s T2-weighted images with prominent WMH in the superior corona radiata and the posterior periventricular regions.

Figure 1.

A: Image of a female age 73 showing no WMH on T2-weighted images. B: Images of Olga’s brain. Arrows point to WMHs in centrum semiovale containing superior corona radiata and the posterior periventricular WM. C: Differences of FA between Olga Kotelko and the reference sample of 58 females (for details see Table 1). Superior corona radiata (SCR), posterior limb of the internal capsule (PLIC), external capsule (EC), fornix (FX), regions of the corpus callosum (CC 1, 2, 5), forceps minor (fMIN), ventral cingulum (vCING), posterior periventricular/occipital WM (OCCIP), prefrontal part of uncinate (pfcUNC), uncinate (UNC), medial temporal lobe WM (MTL), WM of medial PFC (mPFC), WM of the temporal pole (TEMP), and cerebral peduncles (CP).

Contrary to our predictions, Olga’s global FA was greater than the mean global FA of the reference sample. Therefore, to check whether this effect is uniform across all WM tracts or whether there is some regional variation, we performed post-hoc analysis of FA from 22 regions representing main WM tracts (Table 1). In the two regions overlapping with the WMH lesions (SCR and OCCIP), Olga’s FA was the lowest of all of our participants. In the remaining, normal-appearing WM regions (i.e. WM regions not affected by the WMHs) the results were mixed: Olga’s FA was lower than in reference sample in the fornix, external capsule, forceps major, in the parahippocampal WM. Olga’s FA did not significantly differ from the mean FA of the reference sample in the body of corpus callosum, in the anterior cingulate, anterior limb of the internal capsule, forceps minor, and the superior longitudinal fasciculus. In the remaining 10 regions, as well as in the total prefrontal WM, Olga’s FA was significantly higher than the mean FA value of the reference sample. Importantly, in the most anterior portion of the corpus callosum, the genu (CC 1), Olga had the highest FA of all participants. Figure 1-B graphically summarizes the significant FA results.

Cognitive function

Olga’s performance on all tasks was lower than the mean performance of younger-old females, and she performed comparable only on one task measuring fluid intelligence (Letter Sets, Table 2). Interestingly, Olga outperformed the typical nonagenarians on memory and speed tasks (Table 2). With regard to fluid intelligence, she showed better performance on Shipley test and Letter sets, typical performance on Form Board and Spatial Relations, but lower performance on the Matrix and Paper Folding tasks, relative to her age group.

Hippocampal volume

Olga Kotelko’s left and right raw hippocampal volumes were smaller than those of the reference sample. The difference was more robust after correcting for the ICV, as Olga’s ICV was slightly greater than the mean ICV for the reference sample, but her hippocampi were smaller (See Table 1).

Given that the adjusted hippocampal volume was negatively related to age (R HIPPadj r=-.30 p=.025; L HIPPadj r=-.20 p=.135, n=57, Olga excluded), we estimated the regression parameters to predict Olga’s hippocampal volume from the reference sample. Predicted hippocampal volumes for Olga’s bilateral hippocampus were calculated with: R HIPP adj = −15.993 * 93 + 5057.553 and L HIPP adj = −22.793 * 93 + 5626.587, which yielded 3560.204 and 3506.838, respectively. These estimated values were only slightly larger than the actual Olga’s hippocampal volume and were also significantly lower than the mean volumes for the reference sample (1-sample t-test, both p<.001).

Discussion

Olga Kotelko’s brain had significantly greater WMH burden, significantly lower FA especially in regions affected by WMH, and significantly lower hippocampal volume compared to healthy low-active females with a mean age of 66. Contrary to our prediction about accelerated WM integrity decline in very old age, Olga’s global and most of normal-appearing WM showed either same or greater FA than FA of women two decades younger. Most strikingly, Olga had the highest FA of all participants in the genu of the corpus callosum. Finally, Olga outperformed the typical nonagenarians on memory and speed tasks.

Relatively high microstructural integrity in Olga’s normal-appearing WM

Given age-related decline in WM microstructure, Olga’s comparable or greater regional and global FA relative to women 60–78 years old can be considered relatively high for age of 93. Here we consider three alternative underlying explanations:

Higher brain reserve (Satz, Cole, Hardy, & Rassovsky, 2011). Olga might have always had certain health and brain structure advantages, due to genetic, epigenetic, or developmental factors. Thus, she might have had an exceptionally high FA as a child and young adult. Later in life, despite usual age-related deterioration in WM, her FA in the normal-appearing WM might have remained higher than that characteristic of older age. The relatively large ICV of Olga suggests she might have had advantages related to larger brain size.

Successful brain aging. Olga might have had some PA and exercise-unrelated health, lifestyle, or genetic advantage that allowed her to become nonagenarian without any major health problems (i.e., she was in a hospital only twice to give birth). Disease-free aging may have had a twofold beneficial effect on the brain: a) Lack of age-related systemic diseases (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, cancer) may be associated with healthier brain structure and function in old age; b) Lack of disability allows for greater mobility and exploration of the environment. For instance, animal studies show that stimulating, enriched environments prevent spontaneous apoptosis in the brain and are neuroprotective (Young, Lawlor, Leone, Dragunow, & During, 1999).

Remodeling of WM microstructure as a result of PA and exercise. Olga’s WM microstructure might have been remodeled as a result of exercise and training of certain skills related to track-and-field. There is growing evidence that motor learning or cognitive training induces changes in adult white matter that can be captured non-invasively with DTI (Zatorre, Fields, & Johansen-Berg, 2012). Evidence for such plasticity in old age is currently emerging: An 8 week intensive memory training program resulted in preservation of FA in the frontal regions compared to a decrease in FA within control subjects (Engvig et al., 2012), 100 hours of multidomain cognitive training was related to an increase in FA in the anterior part of the corpus callosum (Lövdén et al., 2010), and a36-hours of training of strategic attention, integrated reasoning, and innovation tasks resulted in increased FA in the uncinate fasciculus in older subjects (Chapman et al., 2013). We have shown in two earlier studies that walking aerobic exercise interventions positively affects WM structure in older adults: greater increase in FA in frontal and temporal lobes was related to greater increase in CRF after 1-year intervention (Voss et al., 2012), while regional volume of the anterior corpus callosum increased in the walking group compared to stretching and toning control group after a 6-month intervention (Colcombe et al., 2006).

We do not have Olga’s brain data at any earlier time point and therefore cannot test directly how these three mechanisms contributed to her relatively high FA in the normal-appearing WM at 93. Previous studies on aging and exercise, however, provided rates of age-related decline and aerobic exercise-related gains in FA in older adults. Assuming an annual (quadratic) age-related decrease in FA of 0.75% in the genu of the corpus callosum (Barrick, Charlton, Clark, & Markus, 2010) or 0.24% gain in FA per year of aerobic exercise training (Voss et al., 2012), Olga’s genu FA would have been 0.90 or 0.73, respectively, at the age of 73. We could not find any reports of FA values as high as 0.90 in the genu corpus callosum, even in 3rd decade of life (when FA peaks; e.g. Westlye et al., 2009). Similarly, for the corpus callous, FA peaks at around age of 33 at a value of 0.71, then it decreases to 0.64 at age of 73 and 0.54 at age 93, according to the double polynomial function (Kochunov et al., 2012)1. While the whole corpus callosum mean FA values of 0.68–0.61 reported in this paper for age 60–80 overlap with FA of our reference sample, Olga’s value of 0.77 at age 93 is clearly larger than the estimated 0.54. In fact, her estimated genu corpus callosum FA = 0.73 at the age of 73 (assuming only PA-related gain over two decades) is similar to the values usually reported for young to middle-aged adults (Kochunov et al., 2012) and is well within the range (0.65–0.76) of our low-active reference sample. Cognitive data suggests that exercise at age >85 has an even more dramatic impact on the brain than in younger old adults (Stessman et al., 2009; Sumic, Michael, Carlson, Howieson, & Kaye, 2007). Therefore, we speculate that Olga’s high genu FA was related to both successful aging and beneficial action of PA and exercise.

Myelin integrity may underlie relatively high FA in Olga’s WM

Interestingly, normal-appearing WM regions where Olga showed relatively high FA overlap with regions showing a potential for microstructural remodeling in old age (prefrontal and temporal WM, corpus callosum, uncinate; (Chapman et al., 2013; Engvig et al., 2012; Lövdén et al., 2010; Voss et al., 2012)). Training-related changes in FA are commonly interpreted as changes in the integrity or degree of myelination. Specifically, a recent rodent study combined DTI with histology to show that increases in FA related to motor skill learning were related to increased myelin staining in task-relevant WM regions (Sampaio-Baptista et al., 2013). Therefore, we speculate that normal-appearing WM tracts showing relatively high FA in Olga’s brain have more intact myelin or higher myelin volume fraction, or both.

It is important to note that highest FA was observed in Olga’s genu of the corpus callosum. Microstructure of this region is known to be one of the regions that show the most pronounced age-related deterioration (Sullivan et al., 2001). Low oligodendrocyte-to-axon ratio (Wood P & Bunger RP, 1984), reduced rate of myelin turnover and repair (Hof, Cox, & Morrison, 1990), and high percentage of unmyelinated or thinly myelinated axons (Aboitiz, Scheibel, Fisher, & Zaidel, 1992) makes the fibers of the genu most susceptible to accumulation of metabolic damage. Thus, increased PA, CRF and exercise training may protect against usual age-related deterioration of myelin. For example, exercise in mice was shown to reduce brain oxidative stress and increase neurogenesis (Camiletti-Moirón, Aparicio, Aranda, & Radak, 2013).

Exercise training and PA has the potential to remodel WM microstructure in yet another way, such as by promoting more directional and compact organization of fiber bundles, with more restricted diffusion in the interstitial space between the axons. It is not known yet, however, how such changes would be related to brain health or to cognitive functioning. Alternatively, relatively low levels of myelination in the genu of the corpus callosum may leave more room for PA and exercise-related myelin remodeling and facilitated detection of such changes with DTI than in other, more myelinated WM tracts. Further, intervention studies on WM plasticity using multimodal WM imaging are necessary to define the mechanisms of microstructural remodeling in old and very old age that are captured by differences and changes in FA.

Finally, PA and exercise are known to reduce systemic markers of inflammation (Lakka et al., 2005), while increased inflammatory markers have been associated with lower FA, particularly in the genu (Wersching et al., 2010) of the corpus callosum in healthy non-demented older adults. Although the mechanisms of this association are not yet understood, Olga’s normal-appearing WM might have benefited from 20 years of PA and exercise-related down-regulation of inflammatory markers, which are known to be up-regulated in the aging brain (Lee, Weindruch, & Prolla, 2000).

Together, Olga’s lack of lower FA, relative to younger old females, in the normal-appearing prefrontal and association fibers typical for oldest-old may be related to pro-myelination, neuroprotective, and anti-inflammatory effects of taking up intensive exercise and PA in old age.

High WMH burden and low hippocampal volume in a healthy and active nonagenarian

Olga, despite her regular participation in exercise and no history of hypertension, had significant burden of WMH and lower hippocampal volume than the reference sample.

First, it is very likely that Olga already had WMH at the time she began track-and-field at 77, or even earlier, when she returned to softball at 65. Indeed, large cohort studies report that only less than 5% of non-demented adults older than 60 show no WMH, WMH burden severity progressively increases with advancing age, and women tend to show greater WMH burden than men (de Leeuw et al., 2001).

Second, while age is the main correlate of appearance of WMHs, it is the confluence of lesions at baseline that best predicts their progression, i.e. confluent lesions are more progressive than focal (Schmidt, Enzinger, Ropele, Schmidt, & Fazekas, 2003). Therefore, Olga’s high WMH burden at age 93 may be explained by years-long progression of initial confluent lesions. Interestingly, a large 5-year follow-up cohort study found no relationship between PA and the progression of WMH among older community dwellers (Podewils et al., 2007), or a weak association between WMH around the occipital horns of lateral ventricles and hypertension (Yoshita et al., 2006). Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that progression of WMH in the oldest-old is influenced by other mechanisms than in adults younger than 80. For example, periventricular WMH in the oldest-old may not be entirely ischemic, but related to non-neural changes such as weakening of ventricular lining and infiltration of periventricular tissue with CSF. Indeed, WMH in the very old (>85 years of age) are not necessarily related to dementia or neuropathology such as amyloid angiopathy (Tanskanen et al., 2013).

Third, although Olga’s hippocampal volumes were significantly smaller than of the females over two decades younger, her hippocampal volume could be predicted by the linear slope regressing hippocampal volume over age in the reference sample. This suggests that Olga’s hippocampus underwent steady and not accelerated decline in volume. This is characteristic of successful aging, given that hippocampus shrinkage accelerates in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (Jack et al., 1997; Mungas et al., 2005) as well as in healthy aging (Raz & Rodrigue, 2006; Raz et al., 2004). This relatively slow decline in Olga’s hippocampal volume is consistent with her age-typical or even superior cognitive functioning. It is also possible that her exercise regimen enhanced other mechanisms related to hippocampal function, such as increased neurogenesis/cell survival, increased levels of BDNF, or reduced inflammation (Cotman, 2002; Lakka et al., 2005; Voss, Erickson, et al., 2013), which do not necessarily translate to larger volume in the very old age.

In sum, future longitudinal studies following adults into their very old age are necessary to understand how WMH progression, WM microstructure, and regional brain volumes are related within the aging brain and influenced by PA and fitness. Our report lays a foundation for such studies and suggests non-linear trends between WMH, normal-appearing WM FA, hippocampal size, and cognitive performance in very old age.

Cognitive performance

Although Olga’s performance was lower than that of females almost 3 decades younger, she outperformed typical non-athlete nonagenarians on measures of memory and perceptual speed, and her fluid intelligence performance was on average typical for her age (Birren & Schaie, 2006). Although WM integrity is an important determinant of cognitive performance in aging, the current data allows us only to speculate that Olga’s relatively high (prefrontal) WM integrity and high PA over the last decades were related to her good cognitive scores.

Limitations

Our study’s design is also its main limitation (a single-case study). However, we did not have access to a larger sample of nonagenarians who took up intensive exercise in the 7th decade of life in our area. Still, we think that the description of Olga’s brain health, lifestyle, and cognitive performance adds to the understanding of brain correlates of longevity, nonagenarian brain health, and brain health of aged athletes. Moreover, non-demented and healthy nonagenarians are still underrepresented in neuroimaging studies compared to younger-old population (Yang, Slavin, & Sachdev, 2013)2. We hope that our sharing of Olga’s full images will bring more comprehensive comparisons to her less fit and active peers once such data becomes available.

Another potential limitation could be the difference in the voxel dimension in DTI acquisition between Olga and the reference group. The voxel size for the reference sample was 8.67mm3, while for Olga was 7.03mm3. Smaller voxels result in greater FA values, however, only in regions with crossing fibers (Oouchi et al.). We argue that voxel dimension cannot explain the observed differences between Olga’s and reference sample FA. First, we selected the regions of interest to minimize the overlap with regions containing primarily crossing fibers. Second, the regions were selected on the WM skeleton – the representation of main WM tracts, which minimizes the partial volume effect and restricts the analysis to the center of tracts. Third, if greater FA in Olga’s WM than the reference sample was primarily due to voxel dimension, we should observe FA differences in regions with fiber crossing (SLF), and not in CC, SCR, internal capsule, and CP. As we report Olga’s relatively high FA in CC, no difference in SLF, and consistently lower FA in SCR, which overlaps with WMHs, we conclude that our results can be only minimally affected by differences in the DTI acquisition parameters.

We interpret the meaning of CRF value with caution. Although the graded exercise test procedure is standard and straightforward, Olga’s fitness measures were not obtained on the same equipment and the same location as the reference group. In addition, there is a motivational component to the task, which may affect the result irrespective of the testing site and equipment. It is very possible that Olga (as well as some other participants) terminated the testing based on subjective level of exhaustion and the obtained CRF of 16 (mL/kg/min) is lower than her real CRF. As CRF of at least 15 is considered necessary for independent living for women (Shephard, 2009), we consider Olga’s CRF of 16 good for a nonagenarian. Importantly, age and gender norms for CRF do not cover adults 90 < years of age.

Finally, we performed all testing for Olga on a single visit, and fatigue could negatively affect some of the cognitive testing.

Conclusions

Our findings contribute unique evidence of relatively preserved WM microstructure in very old age and support the possibility of beneficial effects of lifestyle, PA, and exercise on WM, which should be followed by more systematic, longitudinal studies on the rapidly growing population of the oldest-old. The relations between WM microstructure, WMH, hippocampal volume, and cognition in the very old age need further investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Olga Kotelko for her participation in our study and her permission to use her data for scientific purposes. We were very sad to learn about her passing away on June 24th, 2014, while we were preparing this manuscript. We thank Bruce Grierson for providing us with details about Olga’s life and lifestyle. We also thank Chanheng He for help with data management, Holly Tracy and Nancy Dodge for MRI data collection, and Vineet Agarwal for help with calculations.

AZ Burzynska was supported by the Robert Bosch Foundation. The work related to the reference sample was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant (R37-AG025667) and a grant from Abbott Nutrition through the Center of Nutrition, Learning and Memory at the University of Illinois.

Footnotes

Importantly, this study used similar methods for extracting FA values (from the WM skeleton created with TBSS).

To our best knowledge, the brain imaging data from the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study, The 90+ Study, or the Georgia Centenarian Study is not made public.

References

- Aboitiz F, Scheibel AB, Fisher RS, Zaidel E. Fiber composition of the human corpus callosum. Brain Research. 1992;598(1–2):143–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90178-c. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1486477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrick TR, Charlton RA, Clark CA, Markus HS. White matter structural decline in normal ageing: a prospective longitudinal study using tract-based spatial statistics. NeuroImage. 2010;51(2):565–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu C. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system - a technical review. NMR in Biomedicine. 2002;15(7–8):435–55. doi: 10.1002/nbm.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat YA, Beaulieu C. Diffusion anisotropy in subcortical white matter and cortical gray matter: changes with aging and the role of CSF-suppression. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI. 2004;20(2):216–27. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birren J, Schaie K, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 6. San Diego, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Burzynska AZ, Garrett DD, Preuschhof C, Nagel IE, Li SC, Bäckman L, … Lindenberger U. A scaffold for efficiency in the human brain. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33(43):17150–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1426-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burzynska AZ, Nagel IE, Preuschhof C, Li S-C, Lindenberger U, Bäckman L, Heekeren HR. Microstructure of Frontoparietal Connections Predicts Cortical Responsivity and Working Memory Performance. Cerebral Cortex (New York, NY: 1991) 2011 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burzynska AZ, Preuschhof C, Bäckman L, Nyberg L, Li S-C, Lindenberger U, Heekeren HR. Age-related differences in white matter microstructure: Region-specific patterns of diffusivity. NeuroImage. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burzynska, Chaddock-Heyman L, Voss MW, Wong CN, Gothe NP, Olson EA, … Kramer AF. Physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness are beneficial for white matter in low-fit older adults. PloS One. 2014;9(9):e107413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camiletti-Moirón D, Aparicio VA, Aranda P, Radak Z. Does exercise reduce brain oxidative stress? A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2013;23(4):e202–12. doi: 10.1111/sms.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman SB, Aslan S, Spence JS, Hart JJ, Bartz EK, Didehbani N, … Lu H. Neural Mechanisms of Brain Plasticity with Complex Cognitive Training in Healthy Seniors. Cerebral Cortex (New York, NY: 1991) 2013 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombe SJ, Erickson KI, Scalf PE, Kim JS, Prakash R, McAuley E, … Kramer AF. Aerobic Exercise Training Increases Brain Volume in Aging Humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(11):1166–1170. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.11.1166. Retrieved from http://biomedgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/61/11/1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman C. Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends in Neurosciences. 2002;25(6):295–301. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik F, Salthouse T. Handbook of Aging and Cognition. 2. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Achten E, Oudkerk M, Ramos LM, Heijboer R, … Breteler MM. Prevalence of cerebral white matter lesions in elderly people: a population based magnetic resonance imaging study. The Rotterdam Scan Study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2001;70(1):9–14. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.9. Retrieved from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1763449&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edjolo A, Helmer C, Barberger-Gateau P, Dartigues JF, Maubaret C, Pérès K. Becoming a nonagenarian: factors associated with survival up to 90 years old in 70+ men and women. Results from the PAQUID longitudinal cohort. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2013;17(10):881–92. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engvig A, Fjell AM, Westlye LT, Moberget T, Sundseth Ø, Larsen VA, Walhovd KB. Memory training impacts short-term changes in aging white matter: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging study. Human Brain Mapping. 2012;33(10):2390–406. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Gildengers AG, Butters MA. Physical activity and brain plasticity in late adulthood. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2013;15(1):99–108. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.1/kerickson. Retrieved from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3622473&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Prakash RS, Voss MW, Chaddock L, Hu L, Morris KS, … Kramer AF. Aerobic fitness is associated with hippocampal volume in elderly humans. Hippocampus. 2009;19(10):1030–9. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, … Kramer AF. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(7):3017–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow AJ, Bastin ME, Muñoz Maniega S, Valdés Hernández MC, Morris Z, Murray C, … Wardlaw JM. Neuroprotective lifestyles and the aging brain: activity, atrophy, and white matter integrity. Neurology. 2012;79(17):1802–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182703fd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson B. What Makes Olga Run?: The Mystery of the 90-Something Track Star and What She Can Teach Us About Living Longer, Happier Lives. 1. New York: Henry Holt and Co; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman CH, Erickson KI, Kramer AF. Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9(1):58–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof PR, Cox K, Morrison JH. Quantitative analysis of a vulnerable subset of pyramidal neurons in Alzheimer’s disease: I. Superior frontal and inferior temporal cortex. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;301(1):44–54. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Petersen RC, Xu YC, Waring SC, O’Brien PC, Tangalos EG, … Kokmen E. Medial temporal atrophy on MRI in normal aging and very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1997;49(3):786–94. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.3.786. Retrieved from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2730601&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NF, Kim C, Clasey JL, Bailey A, Gold BT. Cardiorespiratory fitness is positively correlated with cerebral white matter integrity in healthy seniors. NeuroImage. 2012;59(2):1514–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochunov, Glahn DC, Rowland LM, Olvera RL, Winkler A, Yang Y-H, … Hong LE. Testing the hypothesis of accelerated cerebral white matter aging in schizophrenia and major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;73(5):482–91. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochunov, Thompson PM, Lancaster JL, Bartzokis G, Smith S, Coyle T, … Fox PT. Relationship between white matter fractional anisotropy and other indices of cerebral health in normal aging: tract-based spatial statistics study of aging. NeuroImage. 2007;35(2):478–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochunov, Williamson DE, Lancaster J, Fox P, Cornell J, Blangero J, Glahn DC. Fractional anisotropy of water diffusion in cerebral white matter across the lifespan. Neurobiology of Aging. 2012;33(1):9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer AF, Hahn S, Cohen NJ, Banich MT, McAuley E, Harrison CR, … Colcombe A. Ageing, fitness and neurocognitive function. Nature. 1999;400(6743):418–9. doi: 10.1038/22682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakka TA, Lakka HM, Rankinen T, Leon AS, Rao DC, Skinner JS, … Bouchard C. Effect of exercise training on plasma levels of C-reactive protein in healthy adults: the HERITAGE Family Study. European Heart Journal. 2005;26(19):2018–25. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CK, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene-expression profile of the ageing brain in mice. Nature Genetics. 2000;25(3):294–7. doi: 10.1038/77046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstreth WT, Manolio TA, Arnold A, Burke GL, Bryan N, Jungreis CA, … Fried L. Clinical correlates of white matter findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging of 3301 elderly people. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke; a Journal of Cerebral Circulation. 1996;27(8):1274–82. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1274. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8711786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Klunk WE, Mathis C, Coleman RL, Price J, Becker J, … Kuller LH. Amyloid, neurodegeneration, and small vessel disease as predictors of dementia in the oldest-old. Neurology. 2014;83(20):1804–1811. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lövdén M, Bodammer NC, Kühn S, Kaufmann J, Schütze H, Tempelmann C, … Schmiedek F. Experience-dependent plasticity of white-matter microstructure extends into old age. Neuropsychologia. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden DJ, Bennett IJ, Burzynska A, Potter GG, Chen NK, Song AW. Diffusion tensor imaging of cerebral white matter integrity in cognitive aging. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2012;1822(3):386–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks BL, Madden DJ, Bucur B, Provenzale JM, White LE, Cabeza R, Huettel SA. Role of aerobic fitness and aging on cerebral white matter integrity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1097:171–4. doi: 10.1196/annals.1379.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey RA, Petty CM, Xu Y, Hayes JP, Wagner HR, Lewis DV, … McCarthy G. A comparison of automated segmentation and manual tracing for quantifying hippocampal and amygdala volumes. NeuroImage. 2009;45(3):855–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungas D, Harvey D, Reed BR, Jagust WJ, DeCarli C, Beckett L, … Chui HC. Longitudinal volumetric MRI change and rate of cognitive decline. Neurology. 2005;65(4):565–71. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172913.88973.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oouchi H, Yamada K, Sakai K, Kizu O, Kubota T, Ito H, Nishimura T. Diffusion anisotropy measurement of brain white matter is affected by voxel size: underestimation occurs in areas with crossing fibers. AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 28(6):1102–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podewils LJ, Guallar E, Beauchamp N, Lyketsos CG, Kuller LH, Scheltens P. Physical activity and white matter lesion progression: assessment using MRI. Neurology. 2007;68(15):1223–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259063.50219.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polvikoski TM, van Straaten ECW, Barkhof F, Sulkava R, Aronen HJ, Niinistö L, … Kalaria RN. Frontal lobe white matter hyperintensities and neurofibrillary pathology in the oldest old. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2071–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d6f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Gunning-Dixon F, Head D, Rodrigue KM, Williamson A, Acker JD. Aging, sexual dimorphism, and hemispheric asymmetry of the cerebral cortex: replicability of regional differences in volume. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004;25(3):377–96. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Rodrigue KM. Differential aging of the brain: patterns, cognitive correlates and modifiers. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2006;30(6):730–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA, Ferrer-Caja E. What needs to be explained to account for age-related effects on multiple cognitive variables? Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(1):91–110. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.1.91. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12641315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio-Baptista C, Khrapitchev AA, Foxley S, Schlagheck T, Scholz J, Jbabdi S, … Johansen-Berg H. Motor skill learning induces changes in white matter microstructure and myelination. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33(50):19499–503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3048-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satz P, Cole MA, Hardy DJ, Rassovsky Y. Brain and cognitive reserve: mediator(s) and construct validity, a critique. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2011;33(1):121–30. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.493151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R, Enzinger C, Ropele S, Schmidt H, Fazekas F. Progression of cerebral white matter lesions: 6-year results of the Austrian Stroke Prevention Study. Lancet. 2003;361(9374):2046–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13616-1. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12814718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shephard RJ. Maximal oxygen intake and independence in old age. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009;43(5):342–6. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.044800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Johansen-Berg H, Jenkinson M, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Miller KL, … Behrens TEJ. Acquisition and voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data with tract-based spatial statistics. Nature Protocols. 2007;2(3):499–503. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.45. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17406613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stessman J, Hammerman-Rozenberg R, Cohen A, Ein-Mor E, Jacobs JM. Physical activity, function, and longevity among the very old. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(16):1476–83. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Adalsteinsson E, Hedehus M, Ju C, Moseley M, Lim KO, Pfefferbaum A. Equivalent disruption of regional white matter microstructure in ageing healthy men and women. Neuroreport. 2001;12(1):99–104. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200101220-00027. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11201100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumic A, Michael YL, Carlson NE, Howieson DB, Kaye JA. Physical activity and the risk of dementia in oldest old. Journal of Aging and Health. 2007;19(2):242–59. doi: 10.1177/0898264307299299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanskanen M, Kalaria RN, Notkola IL, Mäkelä M, Polvikoski T, Myllykangas L, … Erkinjuntti T. Relationships between white matter hyperintensities, cerebral amyloid angiopathy and dementia in a population-based sample of the oldest old. Current Alzheimer Research. 2013;10(10):1090–7. doi: 10.2174/15672050113106660177. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24156259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng BY, Gundapuneedi T, Khan MA, Diaz-Arrastia R, Levine BD, Lu H, … Zhang R. White matter integrity in physically fit older adults. NeuroImage. 2013;82:510–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss MW, Erickson KI, Prakash RS, Chaddock L, Kim JS, Alves H, … Kramer AF. Neurobiological markers of exercise-related brain plasticity in older adults. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2013;28:90–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss MW, Heo S, Prakash RS, Erickson KI, Alves H, Chaddock L, … Kramer AF. The influence of aerobic fitness on cerebral white matter integrity and cognitive function in older adults: Results of a one-year exercise intervention. Human Brain Mapping. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hbm.22119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss MW, Vivar C, Kramer AF, van Praag H. Bridging animal and human models of exercise-induced brain plasticity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2013;17(10):525–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Xu Z, Tang J, Sun J, Gao J, Wu T, Xiao M. Voluntary exercise counteracts Aβ25-35-induced memory impairment in mice. Behavioural Brain Research. 2013;256:618–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Luo X, Barnes D, Sano M, Yaffe K. Physical Activity and Risk of Cognitive Impairment Among Oldest-Old Women. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersching H, Duning T, Lohmann H, Mohammadi S, Stehling C, Fobker M, … Knecht S. Serum C-reactive protein is linked to cerebral microstructural integrity and cognitive function. Neurology. 2010;74(13):1022–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d7b45b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlye LT, Walhovd KB, Dale AM, Bjørnerud A, Due-Tønnessen P, Engvig A, … Fjell AM. Life-Span Changes of the Human Brain White Matter: Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) and Volumetry. Cerebral Cortex (New York, NY: 1991) 2009 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood P, Bunger RP. The biology of the oligodendrocyte. In: WTN, editor. Oligodendroglia. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Slavin MJ, Sachdev PS. Dementia in the oldest old. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2013;9(7):382–93. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye SM, Johnson RW. Increased interleukin-6 expression by microglia from brain of aged mice. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1999;93(1–2):139–148. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(98)00217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshita M, Fletcher E, Harvey D, Ortega M, Martinez O, Mungas DM, … DeCarli CS. Extent and distribution of white matter hyperintensities in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology. 2006;67(12):2192–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249119.95747.1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D, Lawlor PA, Leone P, Dragunow M, During MJ. Environmental enrichment inhibits spontaneous apoptosis, prevents seizures and is neuroprotective. Nature Medicine. 1999;5(4):448–53. doi: 10.1038/7449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ, Fields RD, Johansen-Berg H. Plasticity in gray and white: neuroimaging changes in brain structure during learning. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15(4):528–36. doi: 10.1038/nn.3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]