Abstract

Background

The donation of multiple allografts from a single living donor is a rare practice, and the patient characteristics and outcomes associated with these procedures are not well described.

Methods

Using the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, we identified 101 living multiorgan donors and their 133 recipients.

Results

The 49 sequential (donations during separate procedures) multiorgan donors provided grafts to 81 recipients: 21 kidney-then-liver, 15 liver-then-kidney, 5 lung-then-kidney, 3 liver-then-intestine, 3 kidney-then-pancreas, 1 lung-then-liver, and 1 pancreas-then-kidney. Of these donors, 38% donated 2 grafts to the same recipient and 15% donated 2 grafts as non-directed donors. Compared to recipients from first-time, single organ living donors, recipients from second-time living donors had similar graft and patient survival. The 52 simultaneous (multiple donations during one procedure) multiorgan donors provided 2 grafts to 1 recipient each: 48 kidney-pancreas and 4 liver-intestine. Donors had median of 13.4 years (interquartile range, 8.3-18.5 years) of follow-up. There was one reported death of a sequential donor (2.5 years after second donation). Few postdonation complications were reported over a median of 116 days (interquartile range, 0-295 days) of follow-up; however, routine living donor follow-up data were sparse. Recipients of kidneys from second-time living donors had similar graft (P = 0.2) and patient survival (P = 0.4) when compared with recipients from first-time living donors. Similarly, recipients of livers from second-time living donors had similar graft survival (P = 0.9) and patient survival (P = 0.7) when compared with recipients from first-time living donors.

Conclusions

Careful documentation of outcomes is needed to ensure ethical practices in selection, informed consent, and postdonation care of this unique donor community.

Living donors provide nearly 18% of the organs used for transplantation in the United States each year.1 Kidney and liver donations are the most common and well-studied forms of living organ donation, but living donors in the United States can donate a lung lobe, partial intestine, and even a segment of pancreas with varying degrees of success.2,3 Given the scarcity of organs and the growing transplant waitlist, transplanting multiple grafts from a single living donor might be a potentially useful strategy for a subset of transplant candidates such as pediatric or lower-risk left liver lobe recipients.4 This rare practice is a topic of both clinical and ethical interest; however, there are very few published studies to inform these discussions (Table S1, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B524).

Case series and case reports have documented living multiorgan donation involving a variety of organ pairs, including documentation of simultaneous and sequential liver-kidney, pancreas-kidney, liver-small bowel, and lung-liver living donor transplants from single donors.4–13 Most case series focus on the recipient, with minimal documentation of donor outcomes. In general, recipients of living donor organs experience advantages, including decreased waiting time, decreased cold ischemia time, increased opportunities for immunological matching, and increased graft survival. However, the paucity of data on the outcomes of living multiorgan donors prevents weighing of risks and benefits for the donor candidate, which is important to comprehensive informed consent.14

The goal of this study was to characterize the landscape of living multiorgan transplantation in the United States. Using national registry data, we characterized living multiorgan donors and their recipients and examined outcomes associated with the practice of living multiorgan donation. This study may inform future discussions regarding donor selection, informed consent, and patient education practices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) external release made available in June 2017. The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, waitlisted candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and has been described elsewhere.15 The Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services, provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.

Study Population

The study population consisted of 101 living multiorgan donors and their 133 recipients. Sequential living multiorgan donors were defined as individuals who donated grafts on separate dates (ie, separate procedures). Simultaneous living multiorgan donors were defined as individuals who donated 2 grafts on the same day, presumably during the same procedure. We studied 49 sequential living multiorgan donors with 81 unique recipients and 52 simultaneous living multiorgan donors with 52 unique recipients between March 1994 and January 2017. We compared recipients of the second graft from sequential living multiorgan recipients with recipients of a graft from first-time living donors. For these analyses, we included 140 501 recipients of first-time single-organ living donor kidneys, 6056 recipients of first-time living donor livers, 22 recipients of first-time living donor pancreas, and 38 recipients of first-time living donor intestine transplants recorded in the SRTR registry in the same period.

Statistical Analysis

Groups of living multiorgan donors were compared with the Mann-Whitney rank-sum test (continuous variables) or χ2 test (categorical variables). All-cause graft loss and mortality for recipients of living donor organs were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in patient and graft survival were assessed using the log-rank test of equality. We used a 2-sided alpha of 0.05 to indicate a statistically significant difference. All analyses were performed using Stata 14.2/MP for Linux (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Sequential Living Multiorgan Donation

Sequential Donor Characteristics and Outcomes

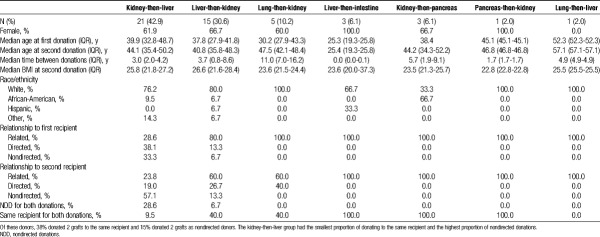

Among the 49 living multiorgan donors who underwent sequential multiorgan donation operations, 21 donated a kidney-then-liver, 15 donated a liver lobe-then-kidney, 5 donated a lung lobe-then-kidney, 3 donated a liver lobe-then-intestine, 3 donated a kidney-then-pancreas segment, 1 donated a lung lobe-then-liver, and 1 donated a pancreas segment-then-kidney (Table 1). These procedures occurred in all 11 United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) regions. The majority of sequential living multiorgan donors were women (65.3%) and white (77.6%), with a median age at first donation of 38 years (interquartile range [IQR], 28-44 years). Median time between donations was 3.7 years (IQR, 1.8-7.0). Sequential liver-then-intestine donors had the shortest time between donations (IQR, 2-40 days). With respect to donor-recipient relationships, there were 17 (34.7%) donors who donated both grafts to the same recipient. There were a total of 22 nondirected donations, of which 59% were liver, and the remainder were kidney. Of these nondirected donations, 8 were from donors who donated 1 organ to a known recipient and 1 in a nondirected manner. Fourteen recipients received grafts in a nondirected manner from 7 sequential donors, who each donated 2 grafts.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of living donors who underwent sequential living multiorgan donation. There were 49 donors who donated organs during separate procedures

Sequential living donors had a median (IQR) 8.3 (3.1-11.5) years of follow-up for patient survival after their second donation. There was 1 reported death in a sequential donor (kidney-liver) 2.5 years after their second donation. Sequential living donors had median 382 (137-741) days of follow-up for other clinical outcomes, as captured by OPTN reporting. There were no reported intraoperative complications for sequential living multiorgan donors in our study. Although follow-up data in the national registry is limited, one kidney-then-liver donor and one liver-then-kidney donor had liver-related complications after their liver graft donations. Four (8.1%) of 49 sequential living multiorgan donors were readmitted between their first donation and their 6-month follow-up, 4 (8.1%) donors were readmitted between their 6-month and 1-year follow-up visit after their first donation, and 2 (4%) donors were readmitted between their second donation and 6-month follow-up visit. Similar to national trends of missing living donor follow-up data,16 sequential living multiorgan donors had high rates of missing follow-up data. Of the 21 donors who donated a kidney second, follow-up data were complete for 52.4% at 6 months, 33.3% at 6 and 12 months, and 4.8% at 6, 12, and 24 months. None of the 22 living donors who donated a liver lobe second had complete 6- or 12-month follow-up.

Sequential Recipient Characteristics and Outcomes

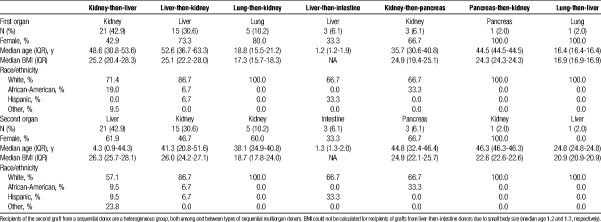

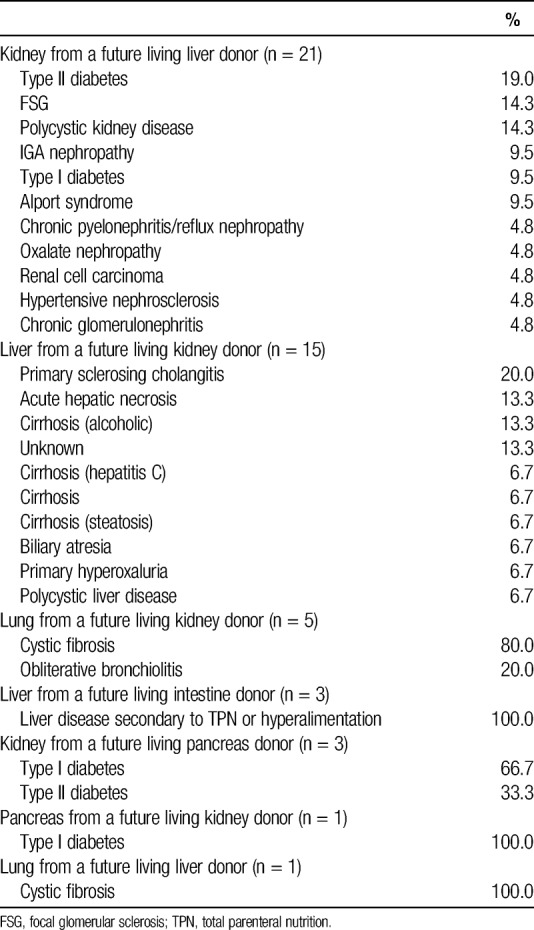

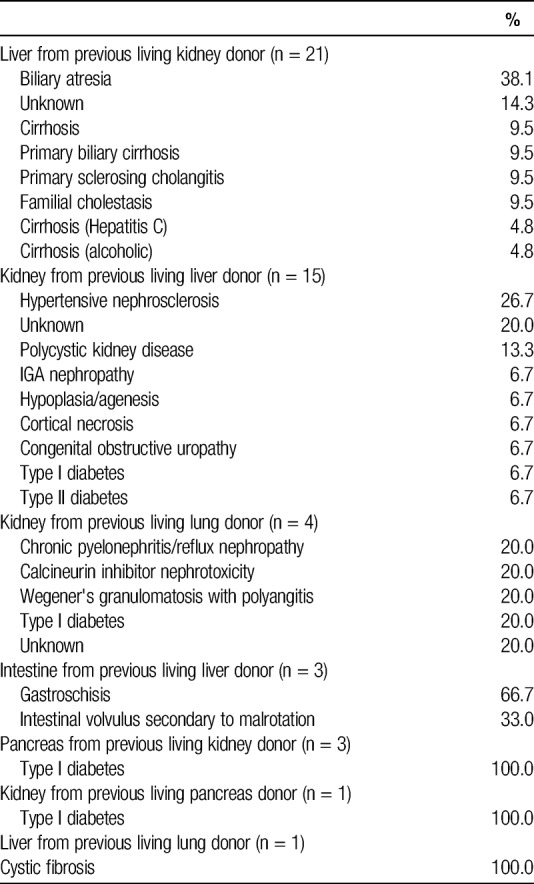

Among recipients of grafts from sequential living multiorgan donors, 57.2% were women and 76.5% were white, with a median age of (39.5) years (IQR, 32-46.5), although recipient characteristics varied by type of sequential donation (Table 2). For example, each liver-then-intestine donor donated two grafts to the same recipient. These recipients were pediatric patients between 1 and 2 years of age whose indication for liver transplantation was liver failure secondary to total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or hyperalimentation (Table 3); their indication for intestinal transplantation was gastroschisis (66.6%) or intestinal volvulus secondary to malrotation (33.3%) (Table 4). In contrast, only 9.5% of kidney-then-liver sequential living multiorgan donors donated two grafts to the same recipient. The recipients of the first graft (kidney) were 42.9% female and 71.4% white, with median age 48.6 (IQR, 30.8-53.6), whereas recipients of the second graft (liver) were 61.9% female and 86.7% white, with median age 4.3 (IQR, 0.9-44.3) (Table 2). There were 6 kidney-then-liver donors (28.6%) who donated both grafts in a nondirected manner (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of recipients who received grafts from sequential living multiorgan donors

TABLE 3.

Principal diagnosis of recipients who received the first graft donated by a sequential multiorgan donor

TABLE 4.

Principal diagnosis of recipients who received the second graft donated by a sequential multiorgan donor

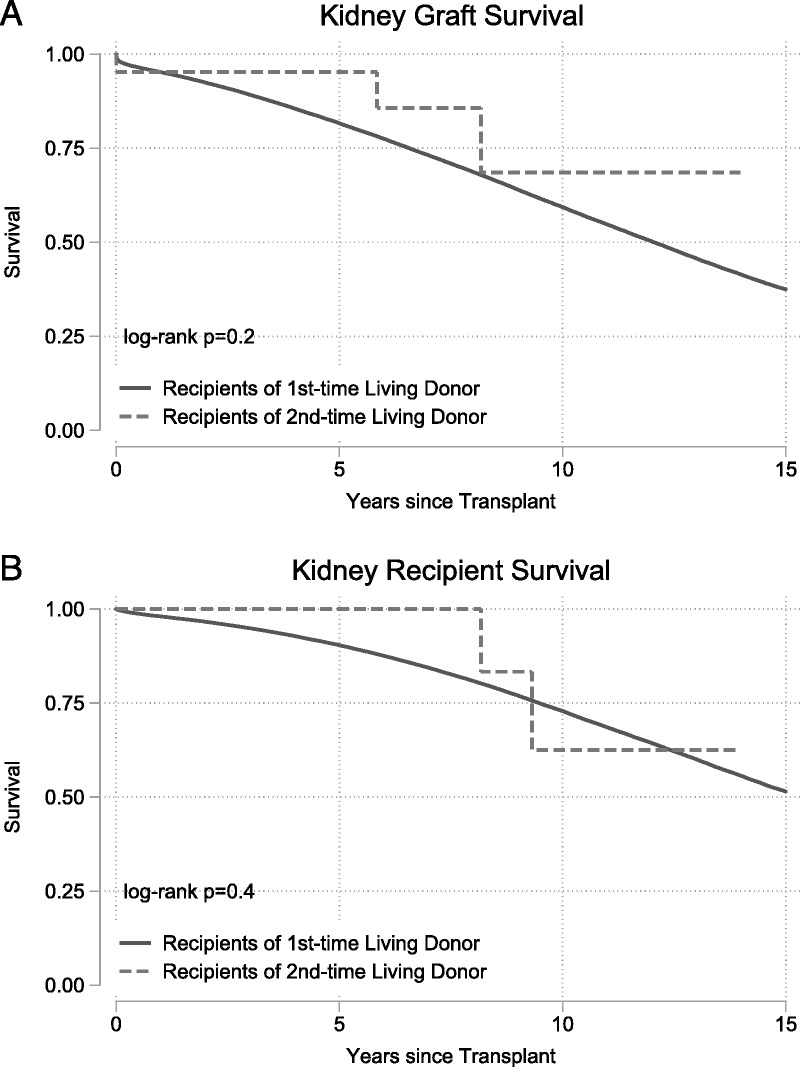

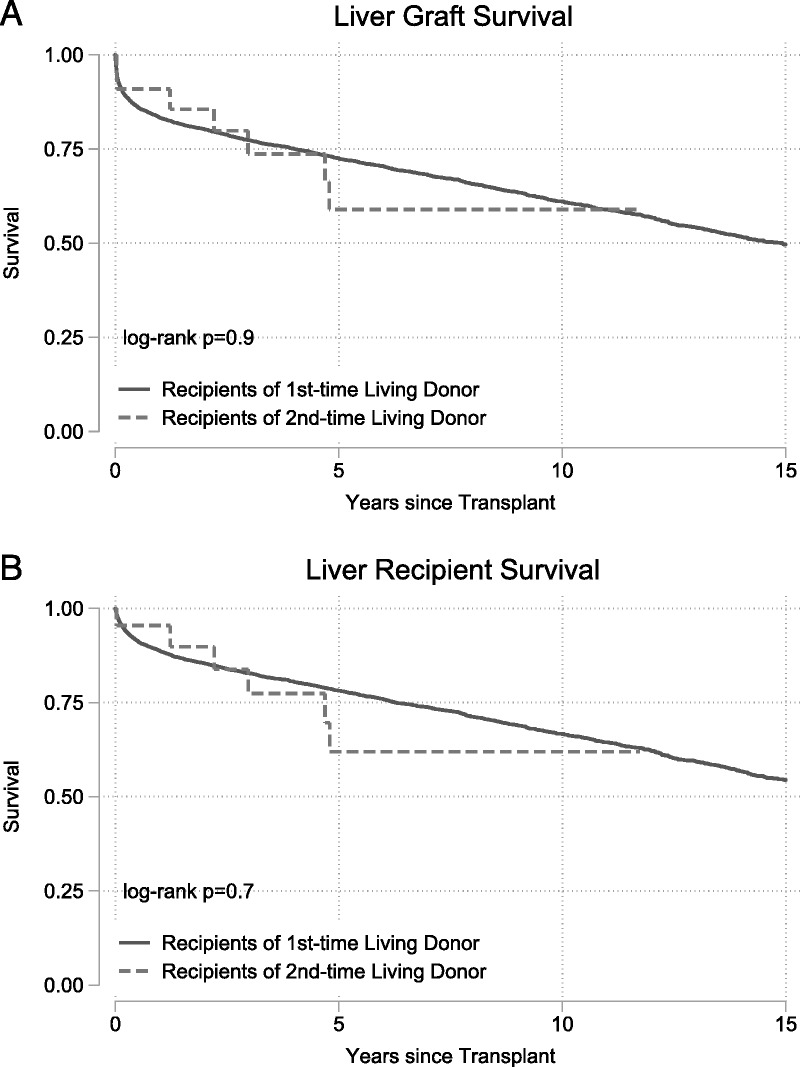

Recipients of kidneys from second-time living donors had similar graft survival (P = 0.2) (Figure 1A) and patient survival (P = 0.4) (Figure 1B) when compared to recipients of kidneys from first-time living donors. Similarly, recipients of livers from second-time living donors had similar graft survival (P = 0.9) (Figure 2A) and patient survival (P = 0.7) (Figure 2B) when compared with recipients of livers from first-time living donors.

FIGURE 1.

Outcomes for living donor kidney transplant recipients. Recipients of kidney graft from first and second time living donors had no differences in (A) death-censored graft failure (P = 0.2) or (B) mortality (P = 0.4).

FIGURE 2.

Outcomes for living donor liver transplant recipients. Recipients of a liver graft from first- and second-time living donors had no differences in (A) death-censored graft failure (P = 0.9) or (B) mortality (P = 0.7).

Simultaneous Multiorgan Donors

Simultaneous Donor Characteristics and Outcomes

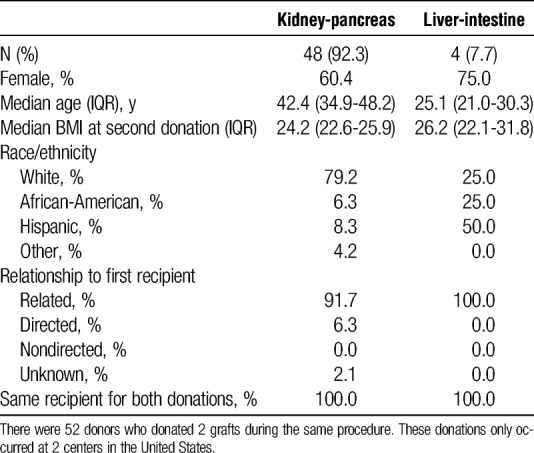

Among the 52 living multiorgan donors undergoing simultaneous donation operations, 48 donated kidney-pancreas and 4 donated liver-intestine grafts. All simultaneous living donation procedures occurred in UNOS region 7. Of these, kidney-segmental pancreas simultaneous multiorgan donors were 60.4% female and 79.2% white, with median age of 42.4 years (IQR, 34.9-48.2 years; Table 5), whereas liver-intestine simultaneous multiorgan donors were 75.0% female and 25.0% white, with median age 25.1 (IQR, 21.0-30.3; Table 6). All 52 (100%) donated both grafts to the same recipient (Table 5). The majority (51.1%) of kidney-pancreas simultaneous living multiorgan donors were siblings of the recipient; the remainder of donor-recipient relationships included both biologically related and nonbiologically related family as well as directed and nondirected donation. All liver-intestine simultaneous multiorgan donors were parents of the recipient. Only 2 transplant hospitals reported performing simultaneous multiorgan donations. One transplant hospital performed 39 kidney-segmental pancreas procedures and 1 liver-intestine procedure, and the second performed 9 kidney-segmental pancreas and 3 liver-intestine procedures.

TABLE 5.

Characteristics of living donors who underwent simultaneous organ donation

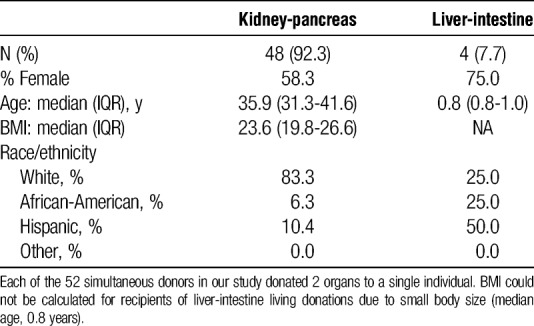

TABLE 6.

Characteristics of recipients who received grafts from a living donor who underwent simultaneous donation

Simultaneous living donors had a median of 18.3 years (IQR, 16.2-20.6 years) of follow-up for survival after their simultaneous donation. There were no simultaneous multiorgan donor deaths reported in the study period. Simultaneous donors had a median of 0 days (IQR, 0-194 days) of follow-up for other clinical outcomes. There were no reported intraoperative or follow-up complications for simultaneous living multiorgan donors. However, 4 (8.35%) of 48 of simultaneous kidney-segmental pancreas donors were readmitted between their donation and 6-month follow-up. One of these donors was also readmitted between their 1-year and 2-year follow-up visits. Like sequential donors, simultaneous living multiorgan donors had high rates of missing follow-up data. None of the 48 kidney donors or the 4 liver donors had complete 6- or 12-month follow-up data.

Simultaneous Recipient Characteristics and Outcomes

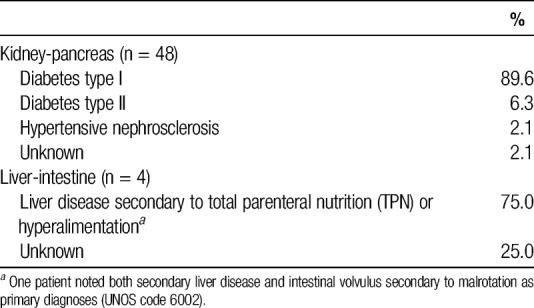

Recipients of grafts from simultaneous kidney-segmental pancreas donors were 58.3% female and 83.3% white, with median age of 35.9 years (IQR, 31.3-41.6 years; Table 6). Type I diabetes was the primary diagnosis of 89.6% of kidney-segmental pancreas recipients; the remainder of kidney-segmental pancreas recipients had type II diabetes (6.3%), hypertensive nephrosclerosis (2.1%), or an unknown primary diagnosis (Table 7). Recipients of grafts from simultaneous liver-intestine donors were 75% female and 25% white, with median age of 0.8 years (IQR, 0.8-1.0 years; Table 6). The primary diagnoses for liver-intestine recipients were liver failure secondary to TPN or hyperalimentation (75%) or unknown (25%).

TABLE 7.

Principal diagnosis for recipients who received grafts from simultaneous living donation

Recipients of kidney-pancreas simultaneous living donor grafts had a median of 14.5 years of kidney graft survival.

Comparison of Select Living Multiorgan Donor Groups

Recipients of kidney-pancreas simultaneous living multiorgan donation were similar to recipients of kidney-then-pancreas and pancreas-then-kidney serial multiorgan donation in sex (P = 0.5), race/ethnicity (P = 0.3), age at first transplant (P = 0.7), body mass index (BMI) (P = 0.9), and primary diagnosis (P = 0.4). Recipients of liver-intestine simultaneous multiorgan donation were younger than recipients of liver-then-intestine serial multiorgan donation (P = 0.03) but similar in sex (P = 0.3), race/ethnicity (P = 0.5), and primary diagnosis (P = 0.2).

DISCUSSION

In this national registry study, we identified 101 living multiorgan donors and their 133 recipients between 1994 and 2017. Among sequential living donors, 38% donated 2 grafts to the same recipient and 15% donated 2 grafts as nondirected donors. Most sequential living donors donated a kidney followed by a liver segment. Simultaneous donation was limited to 2 transplant hospitals and most simultaneous donors donated a kidney and partial pancreas. Living multiorgan donors had a median 13.4 years of follow-up after their second donation and there was one reported sequential donor death 2.5 years after their second donation. There were very few reported complications for living multiorgan donors and their recipients’ outcomes were comparable with recipients of first-time living donors.

Many disease conditions requiring multiorgan transplantation are dire, notably those in the pediatric population where waitlist mortality exceeds 25%.9 Intestinal failure followed by TPN-induced liver failure is a primary cause of disease in this population, and it is common to use deceased organs in these cases.17 In 2005, Testa et al11 reported the first use of living donors to treat this organ failure scenario, and other small series have documented further instances of this practice.

In our national study, there were only 7 cases of liver-then-intestine donation, 3 sequential and 4 simultaneous. In the available literature, provider preference favors sequential donation, providing the liver segment first to correct the coagulopathy and pathology associated with liver failure, then to provide a partial small intestinal graft of ileum into the improved host environment to allow for cessation of TPN dependence and enteral feeding.17 This logical treatment explanation does not take into consideration the risks to the donor, undergoing 2 major abdominal operations in sequence in a relatively short timeframe. It also does not allow for an appreciation of the rarity of living donor small-bowel transplant itself, let alone in the multiorgan donation setting. Despite the first living donor small-bowel transplant being performed 20 years ago, living donors account for less than 1% of small bowel transplants in the United States each year,12 with only 36 documented in the literature before 2006.18 In the case of multiple organ donations, Testa et al11 share that the donor, “underwent double operative stress and was potentially exposed to the complications of 2 major operative procedures.” Although limited by incomplete and missing follow-up data, we found no major reported complications from the 2 operative procedures in our study.

A series of 13 patients undergoing liver-kidney sequential multiorgan donation was published, and the authors were lauded for their use of this novel technique to expand the donor pool in a country with limited access to living donation.4 More than half of the recipients in this group were pediatric, and a mean interval between surgeries was 9.6 months. This length of time between donor operations does allow for donor recovery from hepatectomy before undergoing nephrectomy, and as the authors argue, should not have increased risks above and beyond the risk of having each major operation separately. However, this small case series may underestimate the occurrence of infrequent complications or those that develop in the long-term as donor follow-up is not well described. We identified 15 liver-kidney sequential multiorgan transplants in the US registry, demonstrating that this is a relatively rare procedure nationwide.

Combined with the case series above and a few individual cases documented in other countries, the volume of liver-kidney sequential living multiorgan donation is insufficient to draw conclusions about donor risk.2,7 As one author describes, “Is the ethical issue of the risks to the donor a matter of arbitrarily defining an acceptable risk?”7 Although we agree that conceptualizing risk is often difficult, the transplant community has an ethical obligation to protect living donors from undue harm.19 These uncommon yet emerging procedures require improved and enhanced donor follow-up to build risk profiles prospectively as surgical science advances.

Kidney-pancreas donation comprised the most common form of simultaneous multiorgan donation, with 48 cases identified in the SRTR since 1994. The first living donor simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant was reported in the US in 1994.20,21 Much of the literature on donor outcomes after living pancreas-kidney donation has focused on short-term perioperative complications, rather than long-term complications. Consistent with our findings, no cases of perioperative death have been reported in available literature.20,22 Significant perioperative complications related to pancreatectomy, such as pancreatitis, abscess, or fistula, have been reported in less than 5% of living donors in case series, while reoperation and splenectomy due to bleeding, ischemia, or abscess have been noted in 5% to 20%.22–26 Data on long-term outcomes are limited, but a recent study of 45 living pancreas donors that included 69% simultaneous kidney donations found that over a mean postdonation follow-up period of 16.3 years, 26.7% filled prescriptions for diabetes treatments, compared with 5.9% of kidney-alone living donors (odds ratio, 4.13; 95% confidence interval, 1.91-8.93; P = 0.0003).27 These findings suggest a more than fourfold increase in the incidence of diabetes after living kidney-pancreas donation, a concern that warrants longer follow-up and investigation to adequately understand risks to the donor.

Our study was limited by the small sample size available in the SRTR database, which impacted our ability to measure survival postdonation. Additionally, for certain subgroups, only 2 centers nationally perform these multiorgan donation procedures, making it difficult to draw generalizable inferences. We found follow-up data on living donors to be minimal up to the required 2 years, and even sparser thereafter, which is similar to national trends.16 Particularly for living multiorgan donors who undergo 2 complex surgical procedures, the standardization of long-term follow-up nationwide would help to collect the data necessary to better describe donor risk.

We found that the donation of multiple solid organs from the same living donor is a rare practice in the United States with only 101 cases over the past 2 decades. Careful documentation and postdonation follow-up of these living donors is needed to describe donor risk, to inform appropriate informed consent, and to optimize postdonation care for this very unique community of living donors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation (MMRF) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR, UNOS/OPTN, or the US Government.

Footnotes

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grant numbers K01DK114388-01 (PI: Henderson), F32DK105600 (PI: DiBrito), 4R01DK096008-04 (PI: Segev), 5K01DK101677-02 (PI: Massie), and 5K24DK101828-03 (PI: Segev), 1F32DK109662-01 (PI: Holscher), F30DK116658-01 (PI: Shaffer), and by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) grant number K01HS024600 (PI: Purnell).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

M.L.H., S.R.D. contributed equally to this article.

M.L.H. participated in research design, writing of the article, and performance of the research. S.D.R. participated in research design, writing of the article, and performance of the research. A.G.T. participated in research design, writing of the article, and data analysis. C.M.H. participated in performance of the research and writing of the article. A.A.S. participated in data analysis and writing of the article. M.G.B. participated in data analysis and writing of the article. T.S.P. participated in the writing of the article and performance of the research. A.B.M. participated in the research design and data analysis. J.G.W. participated in the research design and writing of the article. M.M.W. participated in writing of the article. K.L.L. participated in writing of the article and performance of the research. D.L.S. participated in the performance of the research and oversaw the project.

Correspondence: Macey L. Henderson, JD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 2000 E. Monument Street, Baltimore, MD 21205. (macey@jhmi.edu).

Supplemental digital content (SDC) is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.transplantjournal.com).

The authors used SRTR data to characterize living donors who donated more than 1 organ either simultaneously or sequentially. One hundred one cases were identified over the past 2 decades, mostly performed in a small number of centers. One donor died 2.5 years after the second donation but the cause was not recorded and overall, complete follow-up was available for none of the patients. These data are not sufficient to draw conclusions about the value of these procedures. Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hart A, Smith J, Skeans M. OPTN/SRTR annual data report 2014 Am J Transplant 2016. 1611–46 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astarcioglu I, Karademir S, Gülay H. Primary hyperoxaluria: simultaneous combined liver and kidney transplantation from a living related donor Liver Transpl 2003. 9433–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Date H, Aoyama A, Hijiya K. Outcomes of various transplant procedures (single, sparing, inverted) in living-donor lobar lung transplantation J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017. 153479–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldaracena N, Selzner N, Selzner M. Living donation to the extreme: saving a life not once, but twice Liver Transpl 2017. 23288–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humar A, Gruessner RW, Sutherland DE. Living related donor pancreas and pancreas-kidney transplantation Br Med Bull 1997. 53879–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J, Zimmerman MA. Technical aspects for live-donor organ procurement for liver, kidney, pancreas, and intestine Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2015. 20133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marujo W, Barros M, Cury R. Successful combined kidney-liver right lobe transplant from a living donor. Lancet. 1999;353:641. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)05658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacheco-Moreira L, Balbi E, Enne M. One living donor and two donations: sequential kidney and liver donation with 20-years interval Transplant Proc 2005. 374337–4338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raofi V, Beatty E, Testa G. Combined living-related segmental liver and bowel transplantation for megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome J Pediatr Surg 2008. 43e9–e11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan M, Kandaswamy R, Sutherland DE. Laparoscopic donor distal pancreatectomy for living donor pancreas and pancreas-kidney transplantation Am J Transplant 2005. 51966–1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Testa G, Holterman M, John E. Combined living donor liver/small bowel transplantation Transplantation 2005. 791401–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Testa G, Panaro F, Schena S. Living related small bowel transplantation: donor surgical technique Ann Surg 2004. 240779–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zielinski A, Nazarewski S, Bogetti D. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant from living related donor: a single-center experience Transplantation 2003. 76547–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson ML, Gross JA. Living Organ Donation and Informed Consent in the United States: strategies to Improve the Process J Law Med Ethics 2017. 4566–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Segev DL. Big data in organ transplantation: registries and administrative claims Am J Transplant 2014. 141723–1730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson ML, Thomas AG, Shaffer A, et al. The National Landscape of Living Kidney Donor Follow-up in the United States. In: American Journal of Transplantation. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gangemi A, Tzvetanov IG, Beatty E. Lessons learned in pediatric small bowel and liver transplantation from living-related donors Transplantation 2009. 871027–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benedetti E, Holterman M, Asolati M. Living related segmental bowel transplantation: from experimental to standardized procedure Ann Surg 2006. 244694–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abecassis M, Adams M, Adams P. Consensus statement on the live organ donor. JAMA. 2000;284:2919. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruessner R, Kendall DM, Drangstveit MB. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation from live donors. Ann Surg. 1997;226:471. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199710000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruessner R, Leone J, Sutherland DE. Combined kidney and pancreas transplants from living donors. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:282. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)01267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynoso JF, Gruessner CE, Sutherland DE. Short-and long-term outcome for living pancreas donors J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010. 1792–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi JY, Jung JH, Kwon H. Pancreas transplantation from living donors: a single center experience of 20 cases Am J Transplant 2016. 162413–2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenmochi T, Asano T, Maruyama M. Living donor pancreas transplantation in Japan J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010. 17101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirchner VA, Finger EB, Bellin MD. Long-term outcomes for living pancreas donors in the modern era Transplantation 2016. 1001322–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutherland DE, Radosevich D, Gruessner R. Pushing the envelope: living donor pancreas transplantation Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2012. 17106–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam NN, Schnitzler MA, Segev DL. Diabetes mellitus in living pancreas donors: use of integrated national registry and pharmacy claims data to characterize donation-related health outcomes Transplantation 2017. 1011276–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Louis TA, Zeger SL. Effective communication of standard errors and confidence intervals Biostatistics 2009. 101–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]