INTRODUCTION

North America has experienced an overdose epidemic linked across countries related to increased opioid pharmaceutical marketing, opioid prescribing, prescribed and illicit opioid use, and opioid trafficking.1 As a result, greater than 2 million United States inhabitants met criteria for opioid use disorder (OUD) and nearly 5% of US adults reported nonmedical use of opioids in 2013.2 US opioid advertising campaigns and prescribing patterns have spread to Canada.3 In 2012 it was estimated 75,000 to 125,000 Canadians injected drugs, and another 200,000 had OUDs because of pharmaceutical opioids.4 In Mexico, estimates suggest that 100,000 people use illicit opioids and an increasing number of those use heroin.1

In the United States, a large proportion of individuals who use illicit pharmaceutical opioids (68%) report they received the prescription drug from a friend or family member who was prescribed it by their doctor.5 Those that reported heavy, nonmedical opioid use reported that their primary source was direct physician prescribing.6 Thus, physicians have the responsibility to prevent the potential harms of opioids by using sound preventive strategies.

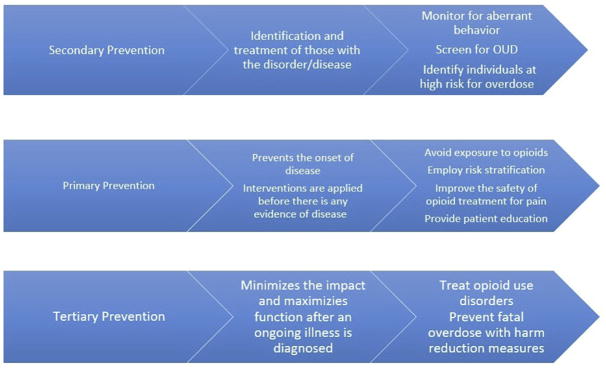

This article describes opioid overdose preventive strategies for medical providers (Fig. 1), with a particular focus on special populations, such as youth and pregnant women. Opioid overdose can occur in any point along the continuum of use, from opioid naivety to long-term opioid use for pain to OUD (Box 1). Furthermore, overdose is caused by a range of factors, including drug interactions, use via injection route, and intentional overdose. We summarize current preventive strategies medical providers in primary care may use to reduce risk throughout the continuum of opioid use and across a range of contributing factors.

Fig. 1.

Levels of overdose prevention.

Box 1. Definitions.

Chronic opioid use: “Daily or near-daily use of opioids for at least 90 days, often indefinitely.”12 Chronic opioid use should be distinguished from an OUD; although it may be associated with tolerance and/or physiologic withdrawal, it does not necessarily involve the other social, behavioral, and compulsive characteristics of an OUD.

Nonmedical use of opioids (or misuse): “Use of a medication (for a medical purpose) other than as directed or as indicated, whether willful or unintentional, and whether harm results or not.”12 Nonmedical use may occur in individuals with or without an OUD.

Aberrant use: “A behavior outside the boundaries of the agreed on treatment plan which is established as early as possible in the doctor-patient relationship.”12 Aberrant use by someone prescribed opioids does not necessarily define an OUD but may raise a provider’s concerns that that individual is developing an OUD.

Diversion: “The intentional transfer of a controlled substance from legitimate distribution and dispensing channels.”12 Individuals with and without OUDs may engage in diversion.

We highlight opioid prescribing guidelines from the Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Canadian Guidelines, last updated February 2017, March 2016, and 2017, respectively.7–9 The recommendations within these guidelines are largely based on observational data; hence the quality of the evidence supporting many recommendations is still moderately weak.10 In addition, overdose prevention research is evolving and recommendations may change based on results from ongoing and new studies. Importantly, existing guidelines focus heavily on limiting prescribing, but a one-size-fits-all approach may not be appropriate or feasible, nor address other facets of the opioid epidemic, such as increasing heroin and nonprescribed fentanyl use. Furthermore, we acknowledge that counseling patients about overdose risk and meeting all opioid prescribing guidelines may be difficult in busy primary care practices, particularly in the face of other competing demands.11

PRIMARY PREVENTION MEASURES

Minimizing Exposure to Opioids Among People Who Are Opioid Naive or Do Not Have an Opioid Use Disorder

Prescribed opioids are associated with an overall 5.5% risk of addiction8 and a 0.2% risk of fatal overdose at a mean of 2.6 years after initial opioid prescription.13 Even opioids prescribed at hospital discharge are associated with an increased risk of chronic opioid use 1 year later.14 Avoiding exposure to opioids may reduce incidence of addiction and death from overdose, hence the first strong recommendation in all three guidelines is nonpharmacologic therapy for pain, such as physical therapy, and, when medications are needed, nonopioid pharmacotherapy, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.7–9,15

History Taking and Risk Evaluation and Mitigation

If opioids are needed for pain, then providers should conduct a thorough history and evaluate the risk of aberrant behavior and overdose (Box 2). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration5 toolkit for providers suggests including specific questions about alcohol and over-the-counter medications.5 To help evaluate the risk of aberrant behavior, commonly used tools are the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain16 and the Opioid Risk Tool.9 Prescription opioids taken in combination with benzodiazepines were found in 30% of opioid overdoses,6 and coprescribing increases the risk of fatal and nonfatal overdose.17 Thus, to mitigate risk, providers should consider alternatives to either benzodiazepines or opioids when coprescribing both medications.8,15

Box 2. Risk groups for overdose.

Chronic medical illness (pulmonary, renal, or hepatic)18

History of substance use disorder19

History of psychiatric disorder20

Controlled substance prescriptions from multiple providers21

Prescribed a combination of opioids and benzodiazepines21

High daily dosages of opioids21

Long-acting and extended-released opioid formulations22

Illicit drug use23

Recent history of incarceration24

History of prior overdose23

Patient Education and Informed Consent

If opioids are used, it is helpful to establish treatment goals, discuss risks and realistic benefits, and consider how opioids will be discontinued if benefits do not outweigh risks.8,9 This discussion should include the responsibilities of the patient and the doctor; potential side effects including sedation, addiction, motor vehicle accidents, and death; limited evidence showing long-term benefits for chronic pain; and the risk of respiratory depression when combined with sedatives.8,9

Considerations on Prescribing Practices to Reduce Overdose Risk

Both dose and duration have a dose-dependent effect on development of overdose, but duration seems to be a stronger predictor of OUD.8,25 Partially because of this, Canadian, Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense, and CDC recommend an upper limit to opioid prescribing (90-mg morphine equivalent dosing). Although research consensus is lacking, there is some evidence that extended-release or long-acting formulations may increase risk of unintentional overdose22; thus the Veterans Affairs and CDC guidelines advise against using longer acting formulations.9 A recent intervention that combined nursing care management, an electronic registry, academic detailing, and electronic decision support tools demonstrated increased adherence to opioid guidelines compared with the group receiving electronic decision support only.26

Safe Storage Practices and Reducing Household Exposure

Parents are an important source of pharmaceutical opioids to children. Exposure may occur through two routes: intentional sharing of opioids for a treatment of a child’s minor aches and pains, or by diversion of pills by an adolescent from their parent’s prescription.27 Counseling on safe storage and disposal practices when providing opioids to an adult with children in the home is also important to protect household members from risky, inadvertent, or recreational exposure.27

Educational Strategies to Prevent Risky Use in Adolescents

Brief universal preventive interventions administered during middle school have been shown to reduce prescription drug misuse among adolescents and young adults.28 The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests providers echo these clear and consistent nonuse messages and provide Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment to their adolescent patients.29 CRAFFT, an age-appropriate Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment intervention, can be used as a screener.30 In those found to be of low risk, brief negotiated interviews may be helpful to reduce risky use of opioids; those of higher risk should be referred to treatment.29

SECONDARY PREVENTION MEASURES

Urine Drug Test

Substance misuse has been shown to be 30% or greater in patients prescribed long-term opiates.31 Although urine drug testing has not been robustly shown to reduce opioid misuse as a stand-alone intervention,31 urine toxicology at initiation of opioids and periodically throughout treatment with appropriate confirmatory testing can help identify patients who warrant further education about opioid safety, evaluation for a substance use disorder (SUD), and referral for treatment.32 Barriers to use of urine toxicology include provider discomfort discussing results, lack of access to testing, inadequate knowledge on how to interpret results, and belief that one’s patients are not at risk of misuse or illicit use.31 In addition, misinterpretation of results or lack of confirmatory testing may lead to falsely accusing patients of diversion or illicit use, hence restricting care to patients and breaking down the therapeutic alliance.31

Prescription Monitoring Programs

Evidence on state-wide prescription monitoring programs (PMP) suggests that they have potential to change prescribing behaviors and identify patients at risk for overdose.15 Although it is still not known if implementation or use decreases overdose deaths, research has suggested some positive effects in isolated states.33–35 Thus, the CDC guidelines suggest checking PMP at the initiation of opioid therapy and at intervals of no greater than 3 months while on treatment.9 The utility of PMPs can be limited. Providers may be unaware of their existence and have difficulty accessing data from other states. In addition, reporting to these systems can be limited.36 These systems also have the potential to lead to inadequate pain care. For example, providers may inappropriately label patients as “doctor shoppers” or become uncomfortable prescribing opioids because they are required to access the system and face risks of criminal sanctions for overprescribing.36

Identifying Nonmedical Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorders

Aberrant behavior has an estimated prevalence of 11.5% among patients prescribed chronic opioid therapy,37 but patients on chronic opioid therapy may be reluctant to disclose risk behavior to their prescribing providers.38 Integrating loved ones into follow-up can bring the provider’s attention to worrisome behaviors and medication use practices. Two screeners have been shown to help identify potential nonmedical use, the Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool and the Current Opioid Misuse Measure.39,40 Providers should evaluate those patients identified with nonmedical or aberrant use for OUD and refer those with OUD to treatment, or initiate OUD treatment in their practices.

Continued Evaluation of Opioid Risk/Benefit Profile and Considering Tapering

The CDC suggests that the marker of clinical improvement is a 30% improvement in both pain and function.9 If these milestones are not achieved with opioid treatment optimization, the physician may consider opioid discontinuation.9 These functional outcomes can be measured with the Pain Average, Interference with Enjoyment of Life41 and Interference with General Activity Assessment Scale.42

When the risks of long-term opioid therapy outweigh benefits, opioid tapering may be considered. Although there are concerns about patients transitioning to heroin after being discontinued or rapidly tapered from opioids,43 several strategies are successful in tapering opioids, such as weekly dose reductions of 10% to 50% of total daily dose.9 To address patients’ concerns of increased pain and withdrawal, support from a trusted health care provider and social support can facilitate a successful opioid taper.44 One review suggested improvement in pain severity, function, and quality of life after dose tapering.45

TERTIARY PREVENTION

Naloxone

Naloxone is an effective, short-acting opioid antagonist that is used for overdose reversal. Based on the successful experience of community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution programs,18,46 which have traditionally targeted people using heroin and other illicit opioids, naloxone is increasingly being prescribed to patients at risk in medical settings. There is evidence to support community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution programs.18 For example, in Massachusetts, communities with high concentrations of naloxone distribution to lay bystanders seemed to have reduced overdose rates.47 Studies have shown that educating lay bystanders about naloxone increases knowledge about how to identify and treat an opioid overdose, with scores that were similar to those of medical experts.48,49 Trained individuals have been able to successfully diffuse this information within their communities.50 Outside of community settings, naloxone has been feasibly implemented in community emergency department settings51 and primary care.41,52

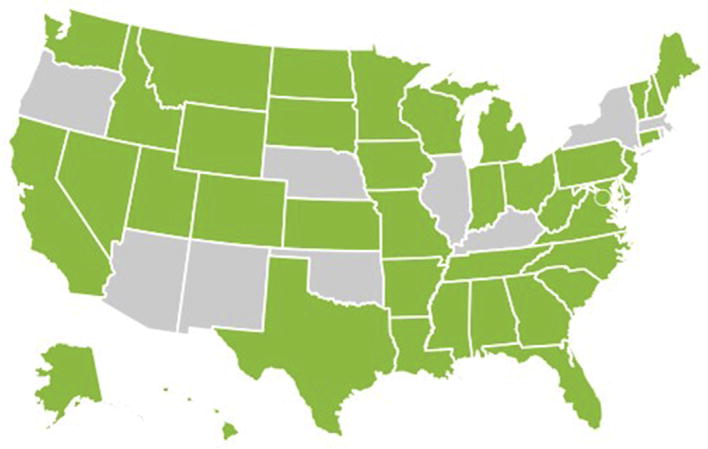

Although the optimal patient groups for naloxone prescription have not yet been determined, naloxone may be considered for patients started on chronic opioid therapy and those who are in the process of tapering or have recently discontinued opioid therapy. Providers may opt to prescribe naloxone to individuals with risk factors for opioid overdose (see Box 2). Table 1 shows groups suggested for naloxone by recent guidelines. In US states where laws allow for it, physicians may prescribe naloxone to family members and lay persons (Fig. 2). For medical providers, the liability risks of prescribing naloxone seem limited.53 Furthermore, some states have implemented standing orders, under which individuals can obtain naloxone from a pharmacy without getting an individual prescription from their provider.

Table 1.

Patient groups to consider for naloxone prescribing, by guidelines

| CDC9 | Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense7 | Canadian8 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Fig. 2.

States that give immunity to prescribers for prescribing naloxone to lay persons (in green) as of July 1, 2017. This figure was created under a Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License. (Adapted from Prescription drug abuse policy system (PDAPS). Legal Science, LLC. Naloxone overdose prevention laws. Available at: http://j.mp/2hDyf2N. Accessed September 30, 2017; with permission.)

Providers may be concerned about increasing risk behavior as a result of naloxone prescribing,11 whereas patients may be concerned about the stigma associated with receiving naloxone.38 In one study, coprescribing naloxone with chronic opioid therapy for noncancer pain was associated with reduced opioid-related emergency department visits.52 Although the reasons for this reduction are unknown, it may be partially caused by the education provided with naloxone, because overdose education combined with motivational interviewing has been shown to reduce self-reported opioid overdose risk behaviors and nonmedical use of prescription opioids.54

Naloxone is available in different formulations. Although the auto-injector and nasal spray are easy to use and avoid the risk of needle stick injuries, the auto-injector is costly and both have variable insurance coverage.55 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has issued an Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit56 and Prescribe to Prevent (prescribetoprevent.org) provides Continuing Medical Education for medical providers.

Treatment of Opioid Use Disorders

Opioid agonist treatment (including methadone and buprenorphine) effectively decreases opioid use and reduces the risk of overdose and death in those with OUDs.57 However, these modalities are vastly underused.58 For buprenorphine, management may occur in primary care settings. In the United States, a buprenorphine Drug Enforcement Administration28 waiver is required for health care practitioners. In Canada, specialized training is suggested but not required.59 Buprenorphine provided in primary care has been shown to be safe and effective.60 In the United States, providers have to refer to specialized methadone treatment centers for their patients to access methadone for addiction.61 Primary care providers can prescribe the opioid antagonist naltrexone in daily oral or monthly injectable form without special licenses, although evidence for reduced overdose rates with naltrexone is currently lacking.

Reducing Risk After Nonfatal Overdose

Those with a previous overdose are commonly considered a high-risk group for repeat overdose; of those prescribed opioids, most continue to be prescribed opioids after overdose.62 The CDC recommends clinicians work with these patients to reduce opioid dosage and prescribe naloxone.9 If opioids are continued, providers should consider incorporating risk mitigation strategies and carefully considering the risks versus benefits of ongoing opioid therapy.9

SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Patients with Psychiatric Disorders

Patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders are more likely to receive an opioid for pain than those without mental health diagnoses,63 and are more likely to receive higher dose opioids, multiple opioids, and benzodiazepines with opioids.64,65 Patients with psychiatric disorders are also less likely to benefit from opioids,66 are more likely to misuse opioids and develop an OUD,67 and are more likely to attempt suicide.68 Guidelines suggest caution in prescribing opioids to those with active, uncontrolled psychiatric illness.7–9 Alternative therapies are preferred, such as tricyclic or serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitor antidepressants for patient with chronic pain and depression/anxiety. Opioid therapy in this population necessitates more frequent follow-up, monitoring, and observation.8,9 When available, consider referring patients with psychiatric conditions to addiction medicine/psychiatry or other behavioral health specialists.7 Complimentary treatment of chronic pain with movement, exercise, and cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain may help pain and mood outcomes and reduce suicide risk.69

Adolescents and Young Adults

Opioid use is common among adolescents.61,70 Adolescents prescribed opioids had a 33% increase in misuse of opiates after high school71; the earlier the exposure to opioids the higher the risk of developing misuse and dependence.7,25,72 All guidelines suggest avoiding opioids in adolescents when possible, and when it is not possible, frequent monitoring and dispensing, close monitoring for aberrancies, and tapering as early as clinically appropriate.7–9

Elderly Patients

Pain management is difficult in the elderly because of increased risks of opioid and nonopioid therapies.73 Because of physiologic changes, opioids may accumulate and increase risk of respiratory depression and overdose.74 Polypharmacy may increase risk of medication interactions and cognitive errors may lead to medication dosages beyond what is prescribed.9,59,75 In patients greater than 65 years of age, additional caution and increased monitoring is suggested when prescribing opioids.9 Prescribers might consider exercise or bowel regimes to prevent constipation, assessing for risk of falls, and monitoring for cognitive impairment.9 Suggestions to improve safety among the elderly include starting at half the starting dose of younger populations, and considering codeine or tramadol first.7,8

Women of Reproductive Age and Pregnant Women

Opioids used in pregnancy are associated with low birth weight, stillbirth, poor fetal growth, preterm delivery, birth defects, cardiac abnormalities, and neonatal abstinence syndrome.76 Severe withdrawal from opioids has been associated with premature labor and spontaneous abortion.8 If a woman is planning to become pregnant, providers may consider opioid tapering and discontinuation before pregnancy.8 For women already taking opioids and pregnant, providers may consider referral or specialized consultation before considering tapering/discontinuing opioids because of potential fetal risks. If a pregnant woman is determined to have an OUD, urgent referral to buprenorphine or methadone management is especially important because these therapies have been associated with improved outcomes.77 However, naltrexone is not recommended.9,78 Codeine is be avoided in breastfeeding mothers, because of possibility of neonatal toxicity and death,8 but breastfeeding is encouraged in mothers prescribed buprenorphine or methadone.79

Patients with Active Substance Use Disorders

Patients with untreated SUDs have significant risk of developing an OUD or experiencing and overdose, suicide, and other cause of mortality.8,19,63,80 Patients with past SUD history, especially if recent, prolonged, or severe, also have elevated risk.8,80,81 Screening for recent SUDs is as simple as a single question “How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or used a prescription medication for nonmedical reasons?”82 Other options for screening include the Drug Abuse Screening Test or the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.9,59,83,84 Guidelines strongly suggest against opioids for chronic noncancer pain in people with an active SUD7,8 because of the risk of addiction to opioids. After nonpharmacologic or nonopioid options, codeine and tramadol are first line for patients with SUD. If higher potency is required, morphine is preferred to oxycodone or hydromorphone.8,59 Referrals are encouraged for patients with continued pain despite buprenorphine and minimal counseling in the primary care setting and for those with comorbid active SUDs when available.7 Unfortunately, successful referral is difficult in clinical practice because access to these services is limited.85

SUMMARY

Prescribers have an important role in prevention of OUDs and opioid overdose. These strategies include minimizing opioid exposure for opioid-naive patients, using risk-mitigation and harm-reduction strategies, and treating OUD. Given that not all interventions are universally appropriate, it is important to consider tailoring preventive efforts to match the individual’s stage of opioid involvement.

KEY POINTS.

Tailor opioid overdose preventive efforts to patients’ individual stage of opioid therapy or involvement; not all interventions are universally appropriate.

Consider risk stratification when treating pain with opioids.

Apply appropriate harm-reduction strategies, such as prescribing naloxone, to patients as risk for overdose.

Consider treatment of opioid use disorders with pharmacotherapy in your own practice.

Acknowledgments

The editors thank Antonio Quidgley-Nevares, Eastern Virginia Medical School, for providing a critical review of this article.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: Dr S.L. Peglow was supported by the Veterans Administration Mental Illness, Research, Education and Clinical Center and by Research in Addiction Medicine Scholars Program-R25DA033211. Dr I.A. Binswanger is supported by the National Institute On Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA042059. The content is solely the responsibilities of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr I.A. Binswanger is currently employed by the Colorado Permanente Medical Group.

References

- 1.Vashishtha D, Mittal ML, Werb D. The North American opioid epidemic: current challenges and a call for treatment as prevention. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0135-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, et al. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and use disorders among adults aged 18 through 64 years in the United States, 2003–2013. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1468–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Zee A. The promotion and marketing of oxycontin: commercial triumph, public health tragedy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):221–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nosyk B, Anglin MD, Brissette S, et al. A call for evidence-based medical treatment of opioid dependence in the United States and Canada. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(8):1462–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Administration SAaMHS. [Accessed August 1, 2017];SAMSHA opioid overdose prevention toolkit: opioid overdose prevention TOOLKIT: information for prescribers. 2013 Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-Opioid-Overdose-Prevention-Toolkit/SMA16-4742.

- 6.Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. [Accessed August 1, 2017];VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. Version 3.0. 2017 Feb; Available at: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/VADoDOTCPG022717.pdf.

- 8.Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189(18):E659–66. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain: United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):276–86. doi: 10.7326/M14-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Binswanger IA, Koester S, Mueller SR, et al. Overdose education and naloxone for patients prescribed opioids in primary care: a qualitative study of primary care staff. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1837–44. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3394-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplovitch E, Gomes T, Camacho X, et al. Sex differences in dose escalation and overdose death during chronic opioid therapy: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, et al. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478–85. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3539-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office of he Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; US Department of Health & Human Services. [Accessed August 1, 2017];Opioid abuse in the US and HHS actions to address opioid-drug related overdoses and death. 2015 Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/opioid-abuse-us-and-hhs-actions-address-opioid-drug-related-overdoses-and-deaths.

- 16.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez K, et al. Validation of a screener and opioid assessment measure for patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2004;112(1–2):65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner BJ, Liang Y. Drug overdose in a retrospective cohort with non-cancer pain treated with opioids, antidepressants, and/or sedative-hypnotics: interactions with mental health disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1081–96. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3199-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller SR, Walley AY, Calcaterra SL, et al. A review of opioid overdose prevention and naloxone prescribing: implications for translating community programming into clinical practice. Subst Abus. 2015;36(2):240–53. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toblin RL, Paulozzi LJ, Logan JE, et al. Mental illness and psychotropic drug use among prescription drug overdose deaths: a medical examiner chart review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(4):491–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05567blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U S Department of Health And Human Services. Opioid abuse in the United States and Department of Health and Human Services actions to address opioid-drug-related overdoses and deaths. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2015;29(2):133–9. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2015.1037530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller M, Barber CW, Leatherman S, et al. Prescription opioid duration of action and the risk of unintentional overdose among patients receiving opioid therapy. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):608–15. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coffin PO, Tracy M, Bucciarelli A, et al. Identifying injection drug users at risk of nonfatal overdose. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):616–23. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison: a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Russo JE, et al. The role of opioid prescription in incident opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with chronic noncancer pain: the role of opioid prescription. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):557–64. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liebschutz JM, Xuan Z, Shanahan CW, et al. Improving adherence to long-term opioid therapy guidelines to reduce opioid misuse in primary care: a cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1265–72. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Binswanger IA, Glanz JM. Pharmaceutical opioids in the home and youth: implications for adult medical practice. Subst Abus. 2015;36(2):141–3. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.991058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spoth R, Trudeau L, Shin C, et al. Longitudinal effects of universal preventive intervention on prescription drug misuse: three randomized controlled trials with late adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):665–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy SJ, Kokotailo PK. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1330–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(6):607–14. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, et al. Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):712–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarvis M, Williams J, Hurford M, Lindsay D, Lincoln P, Giles L, Luongo P, Safarian T. Appropriate use of drug testing in clinical addiction medicine. J addict med. 2017;11(3):163–73. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown R, Riley MR, Ulrich L, et al. Impact of New York prescription drug monitoring program, I-STOP, on statewide overdose morbidity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:348–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haegerich TM, Paulozzi LJ, Manns BJ, et al. What we know, and don’t know, about the impact of state policy and systems-level interventions on prescription drug overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Desai HA. Prescription drug monitoring programs and death rates from drug overdose. Pain Med. 2011;12(5):747–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deyo RA, Irvine JM, Millet LM, et al. Measures such as interstate cooperation would improve the efficacy of programs to track controlled drug prescriptions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(3):603–13. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, et al. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2008;9(4):444–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller SR, Koester S, Glanz JM, et al. Attitudes toward naloxone prescribing in clinical settings: a qualitative study of patients prescribed high dose opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):277–83. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3895-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: diagnostic characteristics of the current opioid misuse measure (COMM) Pain. 2011;152(2):397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Whitcomb L, et al. Monitoring outcomes during long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain: results with the pain assessment and documentation tool. J Opioid Manag. 2005;1(5):257–66. doi: 10.5055/jom.2005.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spelman JF, Peglow S, Schwartz AR, et al. Group visits for overdose education and naloxone distribution in primary care: a pilot quality improvement initiative. Pain Med. 2017;18(12):2325–30. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):154–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1508490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frank JW, Levy C, Matlock DD, et al. Patients’ perspectives on tapering of chronic opioid therapy: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2016;17(10):1838–47. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frank JW, Lovejoy TI, Becker WC, et al. Patient outcomes in dose reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(3):181–91. doi: 10.7326/M17-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, et al. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(23):631–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strang J, Manning V, Mayet S, et al. Overdose training and take-home naloxone for opiate users: prospective cohort study of impact on knowledge and attitudes and subsequent management of overdoses. Addiction. 2008;103(10):1648–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Green TC, Heimer R, Grau LE. Distinguishing signs of opioid overdose and indication for naloxone: an evaluation of six overdose training and naloxone distribution programs in the United States. Addiction. 2008;103(6):979–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sherman SG, Gann DS, Tobin KE, et al. “The life they save may be mine”: diffusion of overdose prevention information from a city sponsored programme. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(2):137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dwyer K, Walley AY, Langlois BK, et al. Opioid education and nasal naloxone rescue kits in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):381–4. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.2.24909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coffin PO, Behar E, Rowe C, et al. Nonrandomized intervention study of naloxone coprescription for primary care patients receiving long-term opioid therapy for pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(4):245–52. doi: 10.7326/M15-2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davis CS, Burris S, Beletsky L, et al. Co-prescribing naloxone does not increase liability risk. Subst Abus. 2016;37(4):498–500. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1238431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bohnert AS, Bonar EE, Cunningham R, et al. A pilot randomized clinical trial of an intervention to reduce overdose risk behaviors among emergency department patients at risk for prescription opioid overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kerensky T, Walley AY. Opioid overdose prevention and naloxone rescue kits: what we know and what we don’t know. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017;12(4):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13722-016-0068-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA opioid overdose prevention toolkit. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4742. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Potter JS, Marino EN, Hillhouse MP, et al. Buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone maintenance treatment outcomes for opioid analgesic, heroin, and combined users: findings from Starting Treatment With Agonist Replacement Therapies (START) J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(4):605–13. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, et al. Medication-assisted therapies: tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kahan M, Wilson L, Mailis-Gagnon A, et al. National Opioid Use Guideline Group. Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain: clinical summary for family physicians. Part 2: special populations. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(11):1269–76. e1419–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Pakes JP, et al. Treatment of heroin dependence with buprenorphine in primary care. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28(2):231–41. doi: 10.1081/ada-120002972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Leftover prescription opioids and nonmedical use among high school seniors: a multi-cohort national study. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(4):480–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larochelle MR, Liebschutz JM, Zhang F, et al. Opioid prescribing after nonfatal overdose and association with repeated overdose. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(5):376–7. doi: 10.7326/L16-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, et al. Trends in use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b99f35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nielsen S, Lintzeris N, Bruno R, et al. Benzodiazepine use among chronic pain patients prescribed opioids: associations with pain, physical and mental health, and health service utilization. Pain Med. 2015;16(2):356–66. doi: 10.1111/pme.12594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wasan AD, Davar G, Jamison R. The association between negative affect and opioid analgesia in patients with discogenic low back pain. Pain. 2005;117(3):450–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, et al. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129(3):355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Im JJ, Shachter RD, Oliva EM, et al. Association of care practices with suicide attempts in US veterans prescribed opioid medications for chronic pain management. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):979–91. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3220-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davidson CL, Babson KA, Bonn-Miller MO, et al. The impact of exercise on suicide risk: examining pathways through depression, PTSD, and sleep in an inpatient sample of veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43(3):279–89. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mazer-Amirshahi M, Mullins PM, Rasooly IR, et al. Trends in prescription opioid use in pediatric emergency department patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(4):230–5. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, et al. Prescription opioids in adolescence and future opioid misuse. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1169–77. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McCabe SE, West BT, Morales M, et al. Does early onset of non-medical use of prescription drugs predict subsequent prescription drug abuse and dependence? Results from a national study. Addiction. 2007;102(12):1920–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology. JAMA. 1998;279(23):1877–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilder-Smith OH. Opioid use in the elderly. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(2):137–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Le Roux C, Tang Y, Drexler K. Alcohol and opioid use disorder in older adults: neglected and treatable illnesses. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(9):87. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0718-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Broussard CS, Rasmussen SA, Reefhuis J, et al. Maternal treatment with opioid analgesics and risk for birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):314.e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, American Society of Addiction Medicine. ACOG committee opinion no 524: opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1070–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256496e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Administration SAaMHS. Clinical use of extended-release injectable naltrexone in the treatment of opioid use disorder: a brief guide. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4892R. [Google Scholar]

- 79.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. [Accessed August 4, 2017];Patient education Fact Sheet: Important information about opioid use disorder and pregnancy. 2016 Available at: https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Important-Information-About-Opioid-Use-Disorder-and-Pregnancy.

- 80.Huffman KL, Shella ER, Sweis G, et al. Nonopioid substance use disorders and opioid dose predict therapeutic opioid addiction. J Pain. 2015;16(2):126–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hser YI, Evans E, Grella C, et al. Long-term course of opioid addiction. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):76–89. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13):1155–60. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yudko E, Lozhkina O, Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the drug abuse screening test. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(2):189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(2):185–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, et al. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e55–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]