Abstract

Purpose

The plasminogen/plasmin system is an important extracellular protease system whose function has been implicated in male reproductive function. However, its clinical relevance to fertility in human assisted reproduction technologies has not been systematically investigated. Here, we examined whether total and active populations of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) in human seminal plasma and spermatozoa are predictive of pregnancy outcome in couples undergoing insemination or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Methods

Seminal samples from 182 men, 5 donors, 21 patients attending the clinic for infertility screening, and 156 for assisted reproduction technology (ART) treatment (insemination and ICSI), were evaluated. Total uPA in seminal plasma and spermatozoa as well as active uPA in seminal plasma were measured by ELISA. Sperm quality parameters and fertility outcomes following insemination or ICSI were correlated with the uPA values.

Results

Active uPA in seminal plasma was positively correlated to the volume of the ejaculate, total number of spermatozoa in the ejaculate, and total motility. However, these values were not prognostic of fertility outcomes. Total uPA in spermatozoa was inversely related to sperm concentration, total sperm in ejaculate, morphology, and total and progressive motility, and this measure was not related to fertility. Importantly, however, higher values of total uPA in seminal plasma were detected in cases that resulted in pregnancy compared to those that did not follow insemination and ICSI treatment.

Conclusions

Taken together, these findings lay the foundation for further understanding the mechanism by which total uPA in seminal plasma affects fertility and how this marker can be used as a predictor of ART outcomes.

Keywords: Plasminogen/plasmin system, Seminal plasma, Spermatozoa, Fertility, Assisted reproduction

Introduction

The plasminogen/plasmin system functions as one of the most important extracellular protease systems in vivo. It participates in different processes related to the degradation of protein matrix, cell migration, tissue remodeling, angiogenesis, and inflammation [1, 2]. It is activated when the zymogen plasminogen is converted into the serine protease plasmin by a complex system. This includes the tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) or the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), and it is regulated by plasminogen activator inhibitors type 1 (PAI-1), type 2 (PAI-2), and type 3 (PAI-3 or protein C), as well as the u-PA-specific receptor (u-PAR) [1, 3].

The plasminogen-plasmin system has also been implicated in male reproductive function. Plasminogen activators have been detected in different locations of the male reproductive tract, such as testis and epididymis [4–6]. Some authors have detected the presence of both plasminogen activators, tPA and uPA [7–9], as well as inhibitors of the plasminogen-plasmin system in human seminal plasma [10, 11]. Animal studies demonstrate the role of this system in spermatogenesis, sperm capacitation, and fertilization [12–17]. Recently, the use of new mice models, such as uPA-immunized male mice [18] and inducible knockout mice of uPA [19], has confirmed the importance of the uPA as a main factor necessary for normal male fertility. The downregulation of uPA decreased the fertility and sperm motility of male mice [19]. Additional animal studies have suggested the importance of uPA and plasminogen/plasmin system in sperm motility, capacitation, and acrosome reaction processes [20–22], and a chemotactic effect of uPA on mouse spermatozoa has been reported [23]. uPA also stimulates human sperm motility [24]. Using the pig model, our group has demonstrated the role of plasminogen-plasmin in the pig fertilization process, showing its activation when the spermatozoa contact the oolemma to elicit a reduction in the number of supernumerary spermatozoa bound to the zona pellucida [14–16].

The majority of the studies have evaluated total concentration of uPA in seminal plasma (ng/mL) and spermatozoa (ng/106 spermatozoa) by radioimmunoassay (RIA) and ELISA techniques [11, 25–28]. Also, plasminogen activator activity (PAA) associated with uPA can be measured in terms of international units per milliliter by spectrophotometry using a chromogenic substrate as S-2251 or Spectrozyme® uPA [27, 29, 30]. PAA is defined as the amount of enzyme needed to transform 1 μmol of plasminogen into plasmin in 1 min per volume unit.

In this study, we investigate a new way of measuring active uPA concentration with aim of identify a new parameter that could be a better biomarker than either total uPA content or enzymatic activity PAA. This method involves measuring the content of active uPA by ELISA (i.e., uPA that is not latent or not complexed), since functionally active uPA forms a covalent complex with the biotinylated PAI-1, which is bound to avidin, whereas inactive or complexed uPA will not bind to avidin and will not be detected.

Although significant amount of work has been done to elucidate the role of uPA in male reproductive function, its relationship to clinical fertility parameters has not been investigated. Although uPA content and PAA in seminal plasma and spermatozoa have been previously related to human seminal parameters [25–28], the possible direct relationship with human fertility has not been comprehensively examined and no conclusive results are available (see Table 1). The aim of this study was to evaluate the concentration of total and active uPA in human seminal plasma and spermatozoa and to determine whether a relationship exists between these values and sperm parameters and fertility outcomes of assisted reproductive treatments. This is the first report, up to our knowledge, measuring active uPA content and showing a direct relationship between total uPA content in seminal plasma and human fertility after artificial insemination with homologous semen (AIH) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and embryo transfer. These results open the possibility for exploring the prognostic value of plasminogen-plasmin system components in seminal samples as predictors of fertilization capacity.

Table 1.

Summary of the measurements of uPA in seminal plasma (SP; ng/mL) and spermatozoa (ng/106 cells) (n cases in brackets)

| Groups | uPA (ng/mL) | P value | Methodology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normozoospermia OAT Azoospermia |

32 ± 14.6 (15) 27 ± 9.2 (41) 19.4 ± 15.4 (11) |

ns | SP RIA |

[23] |

| Normozoospermia Azoospermia |

24.8 ± 11.2 (36) 5.5 ± 0.7 (2) |

< 0.05 | SP ELISA |

[25] |

| First fraction Second fraction |

27.9 ± 6.1 (12) 14 ± 3.4 (12) |

< 0.05 | SP ELISA |

[25] |

| Healthy volunters | 15.5 ± 5 (20) | – | SP ELISA |

[19] |

| First fraction Second fraction |

25 ± 8 (2) 5.1 ± 2.8 (2) |

< 0.05 | SP ELISA |

[19] |

| Normozoospermia Oligozoospermia OAT |

5.4 (44) 5.7 (38) 3.5 (10) |

ns | SP ELISA |

[20] |

| Normal volunters Patients infertility |

25.5 (10) 28.5 (10) |

ns | SP ELISA |

[22] |

| Normozoospermia A Normozoospermia B No normozoospermic |

24 (52) 25.6 (52) 22.6 (52) |

ns | Total ejaculate ELISA | [21] |

| Normozoospermia OAT Azoospermia |

26.2 ± 12.4 (124) 24.6 ± 11.4 (18) 18.4 ± 9.2 (28) |

ns | SP | [32] |

| Normozoospermia (16) Asthenozoospermia (21) |

– – |

ns | SP mRNA |

[34] |

| Normozoospermia (15) OAT (41) |

1.6 ± 0.2 (15) 7.7 ± 2.1 (41) |

< 0.05 | Spermatoza ng/106 cells |

[23] |

OAT oligoasthenoteratozoospermia, ns not significant

Material and methods

Ethics

This study was conducted with institutional approval from Instituto Valenciano de Infertilidad (Ref. 1210-MU-109JM). Couples undergoing assisted reproduction treatment in Instituto Valenciano de Infertilidad (IVI-Murcia, Spain) and sperm donors were included after signing the informed consent.

Sample collection and sperm assessment

This research was an observational case control study. Semen samples were obtained from 182 men: 5 donors, 21 patients attending the clinic for infertility screening, and 156 for assisted reproduction technology (ART) treatment (IAH and ICSI). The men ranged in age from 18 to 59 years, with a mean value of 36.41 ± 0.42 years. Semen samples were obtained by masturbation and collected into sterile containers, following 3–5 days of abstinence from sexual activity. After liquefaction, semen samples were examined for volume, sperm concentration, morphology and motility according to World Health Organization (WHO), fifth edition guidelines [31]. Samples were categorized into the following groups: normozoospermia (n = 145), oligozoospermia (n = 3), asthenozoospermia (n = 23), and oligoasthenozoospermia (n = 11), according to WHO criteria [31]. Oligozoospermia was considered when the total number of spermatozoa in the ejaculate was below 39 × 106 spermatozoa. Asthenozoospermia was considered when percentage of progressively motile spermatozoa was below 32% [31].

Determination of uPA concentration

Aliquots of each sample were centrifuged (3000×g for 10 min), and seminal plasma and spermatozoa were stored separately at − 80 °C until their uPA content was evaluated.

For measurements of the total and active uPA concentration in seminal plasma (ng/mL), ELISA kits from Molecular Innovation Inc. (Novi, MI, USA) were used (human uPA total antigen assay and human uPA active). Total uPA evaluation in spermatozoa (expressed as ng/106 cells) was measured in sonicated samples. Briefly, spermatozoa were resuspended in PBS and centrifuged at 3000×g twice. Sperm suspension was transferred to a beaker in ice water (0 °C) and sonicated for 15 s at 50% outpour of a sonicator (Labsonic, B. Braun Biotech International, Melsungen, Germany). In the total uPA assay, uPA present in the sample binds to the polyclonal antibody coated on the microtiter plate. Free and complexed uPA is detected by the assay in the 0.1–50 ng/mL range. The minimum detectable value was 0.043 ng/mL. A standard calibration curve was prepared along with the samples to be measured using serial dilutions of uPA. In the human uPA active assay, functionally active uPA present in samples forms a covalent complex with the biotinylated human PAI-1 which is bound to the avidin on the plate. The assay measures active uPA in the 0.1–50 ng/mL range. The minimum detectable value was 0.013 ng/mL. The presence of uPA in seminal plasma and spermatozoa was confirmed by Western blotting, using anti-uPA polyclonal antibody from goat (1:1000 v/v, AP02255SU-N, Acris antibodies GmbH, Herford, Germany) and rabbit anti-goat IgG-HRP conjugate antibody (1:10,000 v/v, AP106P, Millipore, Madrid, Spain).

Assisted reproductive treatments

According to the reproductive pathology diagnosis, the couples were treated with artificial insemination with homologous semen (AIH) or ICSI. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were different according to the corresponding ART.

AIH treatment

AIH inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for AIH included women between 18 and 39 years old undergoing ovarian stimulation with clinical criteria for AIH and confirmatory tubal patency. Women with severe endometriosis or uterine fibroids over 2 cm that disturbed the endometrial lining were excluded. Inclusion criteria for men included number of progressively motile spermatozoa (NPMS) greater than 2 million cells.

AIH procedures

Semen parameters were evaluated after liquefaction at 37 °C under 5% CO2, for 10–30 min. The samples were examined for sperm concentration and motility in a Makler® Chamber (Sefi Laboratories, Tel Aviv, Israel). All samples were processed by swim-up or density gradient methods. Briefly, in the swim up method, ejaculates were diluted 1:1 (v/v) with Sperm Medium (Global fertilization, Life global, Guilford, USA), centrifuged at 300×g for 10 min, and the supernatant eliminated. Aliquots of 0.5–1 mL of fresh medium were overlaid over the pellet and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min with the tubes inclined at an angle of 45°. After this period, the upper layer (0.5 mL), containing the sperm to be used in the treatment, was taken. In the density gradient method (90 and 45%, All grad, Life global, Guilford, USA), sperm suspension was layered gently over the 45% medium and centrifuged at 200×g for 20 min. Pellets were washed again at 300×g for 5 min after centrifugation; supernatant was removed, and the pellet, containing the sperm to be used in the treatment, was resuspended in 0.5 mL of sperm medium. Aliquots of 10 μL were used for analysis of sperm concentration, motility, and morphology. The remaining sample was loaded into the insemination catheter and delivered into the uterus.

All cycles were stimulated with recombinant FSH (Puregon; MSD, Spain). Stimulation was started on cycle day 3 with 50–75 IU of rFSH daily. Follicle maturation was monitored by serial vaginal ultrasound and plasma E2 levels. When the diameter of the leading follicle(s) was > 18 mm, the patients received 6500 IU of HCG (Ovitrelle, Merck Serono, Madrid, Spain). Inseminations were performed 12 and 36 h after the HCG injection. The luteal phase was supported by daily vaginal administration of 200 mg progesterone suppositories. Plasma β-HCG levels were measured 2 weeks after IAH to determine biochemical pregnancy. Clinical pregnancy was defined as transvaginal ultrasonographic visualization of intrauterine gestational sac(s).

ICSI treatment

ICSI inclusion and exclusion criteria

Women who were between 18 and 39 years old and undergoing ovarian stimulation were included. Men were included when the number of progressively motile spermatozoa (NPMS) was greater than 0.7 million spermatozoa. Women were excluded in cases of presence of uterine fibroids over 2 cm that disturbed the endometrial lining.

ICSI procedures

All patients were stimulated with GnRH antagonist treatments (Orgalutran, MSD) and recombinant or urinary FSH (Puregon; MSD, Gonal-F; Merck Serono or Fostipur; Angelini). Follicle maturation was monitored by serial vaginal ultrasound and plasma E2 and P4 levels. When the diameter of the leading follicle(s) was > 18 mm, the patients received 6500 IU of HCG (Ovitrelle, Merck Serono, Madrid, Spain) and transvaginal oocyte retrieval was performed 36 h later. Oocytes were inseminated by ICSI method, and oocytes were placed individually in pre-equilibrated culture dishes (EmbryoSlide; Vitrolife AB, Göteborg, Sweden) in a time-lapse incubator (EmbryoScope¸ Vitrolife AB, Göteborg, Sweden) or in a conventional incubator (Heraeus; Heracell, Madrid, Spain) under oil at 37 °C and 5.5% CO2 in air.

Luteal phase was supported by daily vaginal administration of 400 mg progesterone suppositories. Plasma β-HCG levels were measured 2 weeks after embryo transfer to determine biochemical pregnancy. Clinical pregnancy was defined as transvaginal ultrasonographic visualization of intrauterine gestational sac(s).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. and analyzed by ANOVA, considering the specific group as the main variable. When ANOVA revealed a significant effect, values were compared by the least significant difference pair wise multiple comparison post hoc test (Tukey). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Pearson correlation was used to explore the possible relationships between uPA concentration and seminal parameters. Correlations were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Logistic regression was used for comparing the sperm parameters values between pregnant and non-pregnant cases.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was applied to evaluate the predictive value of the fertility (pregnancy rate %) of the uPA concentration in seminal plasma. Sensitivity, specificity and cutoff value was calculated. Finally, the positive and negative likelihood ratios are defined respectively as follows: LR+ = probability of positive test given the presence of pregnancy/probability of positive test given the absence of pregnancy = sensitivity/1 − specificity. LR− = probability of negative test given the presence of pregnancy/probability of negative test given the absence of pregnancy = 1 − sensitivity/specificity.

Systat 13 and SigmaPlot 13 software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) were used for the statistical analysis and graphical presentation.

Limitations of the study

Due to logistical issues, it was not possible to measure all the parameters in each seminal sample (details in Table 2). The number of samples evaluated for every parameter is shown in the tables and pairwise comparison was done in correlation studies.

Table 2.

Sperm parameters evaluated and reproductive outcomes

| Sperm parameters | N of cases | Mean ± SEM | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (mL) | 182 | 3.52 ± 0.14 | 0.60–9.20 |

| Sperm concentration (106/mL) | 182 | 47.97 ± 2.89 | 2.50–180 |

| Total sperm in ejaculate (106) | 182 | 166.38 ± 12.18 | 8.80–770 |

| Motility (%) | 182 | 53.93 ± 1.25 | 11–84 |

| Progressive motility (%) | 182 | 44.27 ± 1.15 | 5–76 |

| Normal morphology (%) | 154 | 3.96 ± 0.25 | 0–22 |

| Total uPA seminal plasma (ng/mL) | 66 | 22.34 ± 0.77 | 7.08–36.75 |

| Active uPA seminal plasma (ng/mL) | 150 | 1.64 ± 0.12 | 0.04–7.64 |

| Total uPA spermatozoa (ng/106 cells) | 68 | 1.21 ± 0.19 | 0.04–8.21 |

| Pregnancy rate after AIH (%) | 78 | 20.51 | |

| Pregnancy rate after ICSI (%) | 51 | 50.98 |

Results

uPA in seminal plasma and spermatozoa

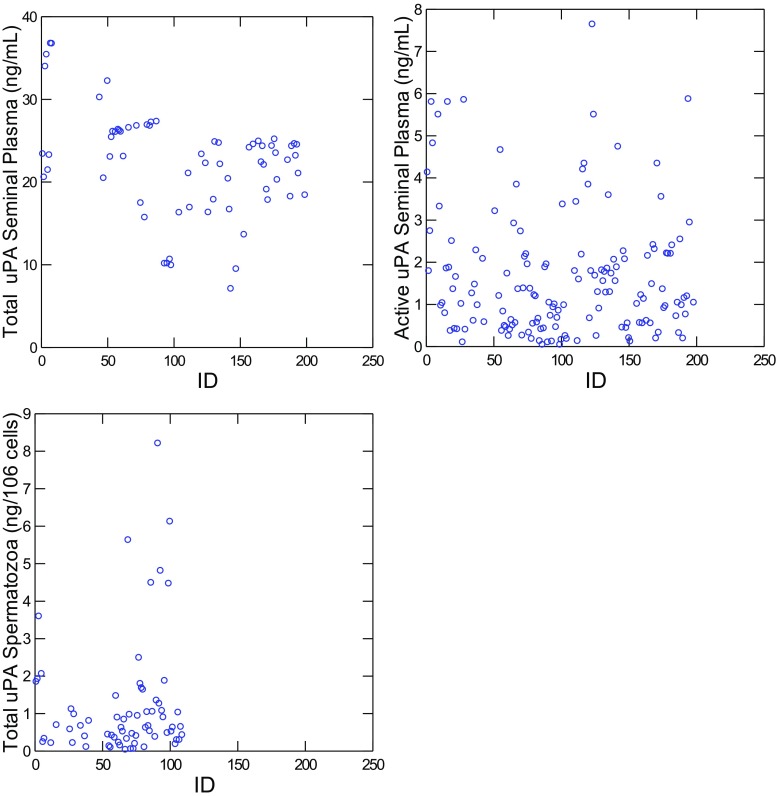

Sperm parameters (sperm concentration, total sperm in ejaculate, morphology and total and progressive motility) and total uPA concentration in seminal plasma (ng/mL), active uPA concentration in seminal plasma (ng/mL), and total uPA concentration in spermatozoa (expressed as ng/106 spermatozoa) are shown in Table 2. Mean values for total and active uPA in seminal plasma were 22.34 ± 0.77 and 1.64 ± 0.12 ng/mL, respectively (Table 2) with a heterogeneous distribution of the samples (Fig. 1). The mean value for total uPA in spermatozoa was 1.21 ± 0.19 ng/106 spermatozoa.

Fig. 1.

Values for uPA total (n = 66) and active uPA (n = 150) concentration in seminal plasma (ng/mL), uPA total in spermatozoa (n = 68; ng/106 cells) for seminal samples. ID: patient clinical number (n = 182)

In 54 cases, it was possible to evaluate total and active uPA in seminal plasma from the same sample with values of 21.91 ± 0.75 ng/mL total uPA and 1.74 ± 0.21 ng/mL of active uPA. These parameters were not significantly related (Pearson correlation (r = 0.13, P > 0.05). The active uPA represented, in most of the cases, less than 10% of the total uPA present in the seminal plasma (mean value 8.27 ± 1.02%).

In 59 cases, it was possible to evaluate active uPA in seminal plasma and uPa content in spermatozoa from the same sample with values of 1.38 ng/mL of active uPA and 1.23 ng/106 spermatozoa. These parameters were not significantly related (Pearson correlation; r = − 0.17, P > 0.05).

Relationship between uPA content and sperm parameters

Total uPA content in seminal plasma was not related to the seminal parameters (P > 0.05; Table 3), whereas active uPA in seminal plasma was positive and significantly related to the volume of the ejaculate, total number of spermatozoa in the ejaculate (× 106) and total motility (%, P < 0.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation between uPA concentration in seminal plasma or spermatozoa and the seminal parameters

| Total uPA seminal plasma (ng/mL) | Active uPA seminal plasma (ng/mL) | Total uPA spermatozoa (ng/106 cells) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (mL) | 0.06 (64) | 0.18* (148) | − 0.04 (68) |

| Concentration (106/mL) | 0.16 (64) | 0.10 (148) | − 0.48** (68) |

| Total sperm in ejaculate (106) | 0.19 (64) | 0.19* (148) | − 0.39** (68) |

| Motility (%) | 0.08 (64) | 0.22* (148) | − 0.35** (68) |

| Progressive Motility (%) | 0.16 (64) | 0.10 (148) | − 0.31* (68) |

| Normal morphology (%) | − 0.01 (51) | 0.16 (126) | − 0.27* (59) |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

For total uPA in spermatozoa, an inverse and significant relationship was found to most of the seminal parameters (concentration, total sperm in ejaculate, morphology, and total and progressive motility) (P < 0.05; Table 3).

When samples were grouped by normozoospermia (n = 145), oligozoospermia (n = 3), asthenozoospermia (n = 23), and oligoasthenozoospermia (n = 11), according to WHO criteria [31], no differences were found for total and active uPA in seminal plasma between groups (P = 0.53 and P = 0.36, respectively; Table 4). However, higher values for uPA in spermatozoa (ng/106 cells) were detected in non-normozoospermic than normozoospermic samples (P < 0.01; Table 4). This result is consistent with the inverse relationship between uPA in sperm (ng/106 cells) and sperm parameters (P < 0.05; Table 3).

Table 4.

uPA concentration and sperm parameters in samples grouped in normozoospermic and no-normozoospermic (n)

| Sperm parameters | Normozoospermia | Oligozoospermia | Asthenozoospermia | Oligoasthenozoospermia | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (mL) | 3.59 ± 0.12 (123) |

3.07 ± 0.97 (3) |

3.40 ± 0.29 (23) |

2.99 ± 0.39 (11) |

0.52 |

| Sperm concentration (106/mL) | 53.22 ± 2.55a (145) |

7.67 ± 2.67b (3) |

38.78 ± 4.04ª (23) |

8.93 ± 1.74b (11) |

< 0.01 |

| Total sperm in ejaculate (106) | 186.45 ± 10.70a (145) |

21.20 ± 5.70b (3) |

127.65 ± 15.72a (23) |

23.37 ± 13.07b (11) |

< 0.01 |

| Motility (%) | 57.59 ± 0.90a (145) |

62.33 ± 7.22a (3) |

38.48 ± 3.21b (23) |

35.82 ± 4.38b (11) |

< 0.01 |

| Progressive motility (%) | 48.94 ± 0.76a (145) |

48.67 ± 7.33a (3) |

24.74 ± 1.59b (23) |

22.45 ± 1.83b (11) |

< 0.01 |

| Normal morphology (%) | 4.20 ± 0.32 (122) |

2 ± 1 (2) |

3.60 ± 0.63 (23) |

2.20 ± 0.63 (10) |

0.24 |

| Total uPA seminal plasma (ng/mL) | 22.79 ± 0.89 (49) |

24.55 (1) |

21.24 ± 2.05 (10) |

18.38 ± 3.82 (4) |

0.53 |

| Active uPA seminal plasma (ng/mL) | 1.75 ± 0.15 (117) |

1.64 ± 1.09 (2) |

1.13 ± 0.19 (20) |

1.37 ± 0.31 (9) |

0.36 |

| Total uPA spermatozoa (ng/106 cells) | 0.95 ± 0.15a (56) |

3.30 ± 2.33b (2) |

1.12 ± 0.38a (8) |

6.51 ± 1.70b (2) |

< 0.01 |

a,b Numbers within columns with different letters differ (P < 0.05)

uPA concentration in seminal plasma and spermatozoa and fertility outcomes

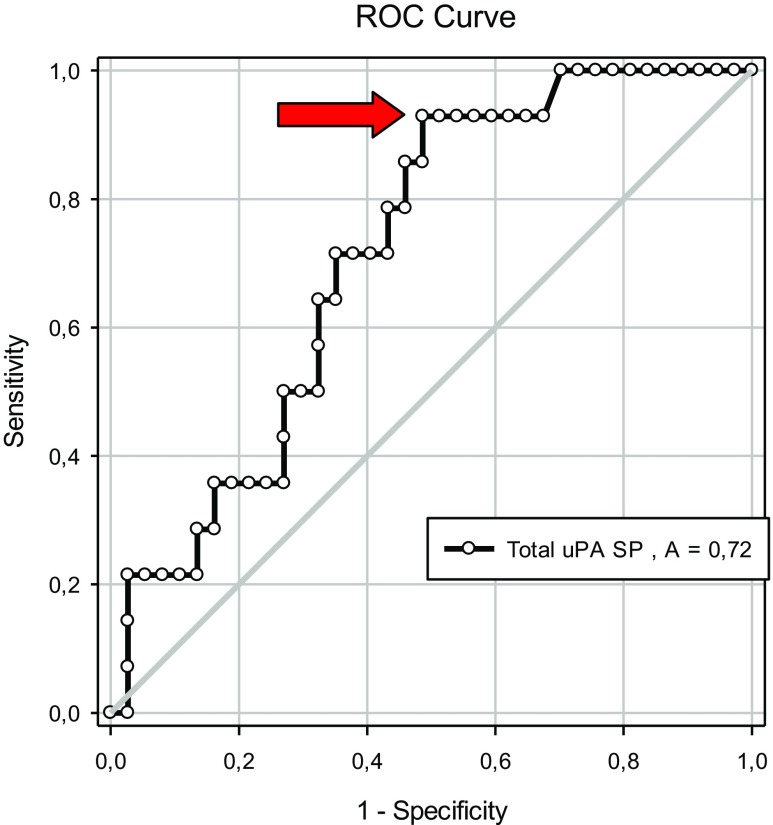

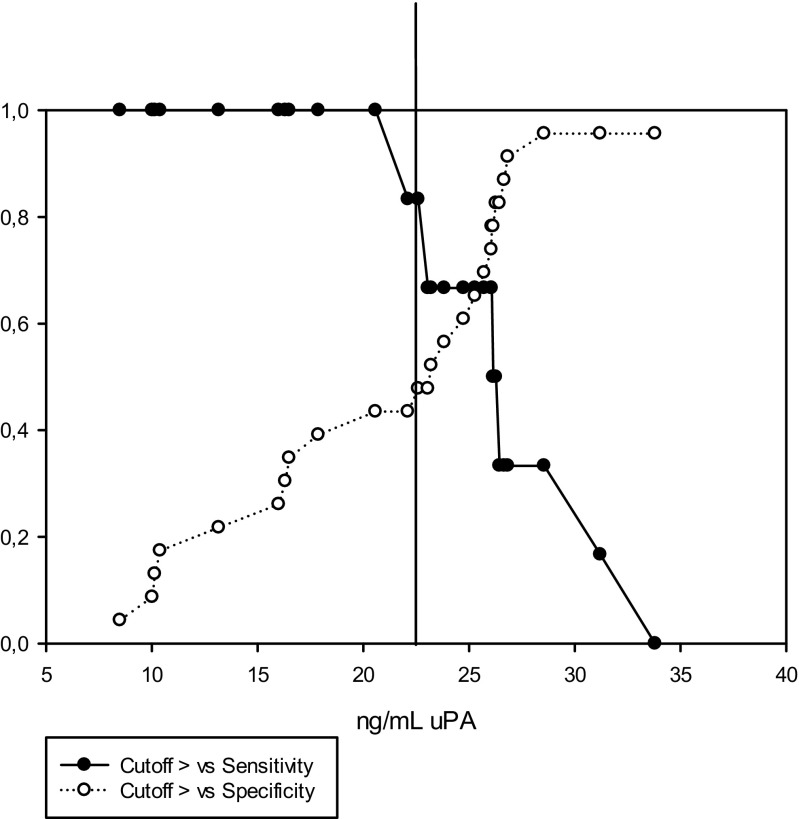

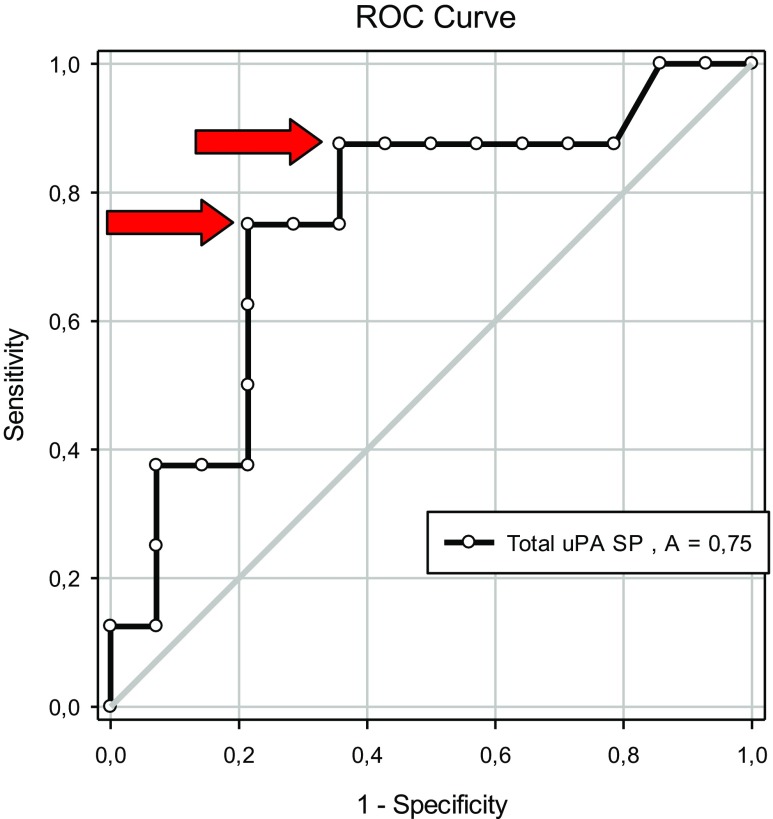

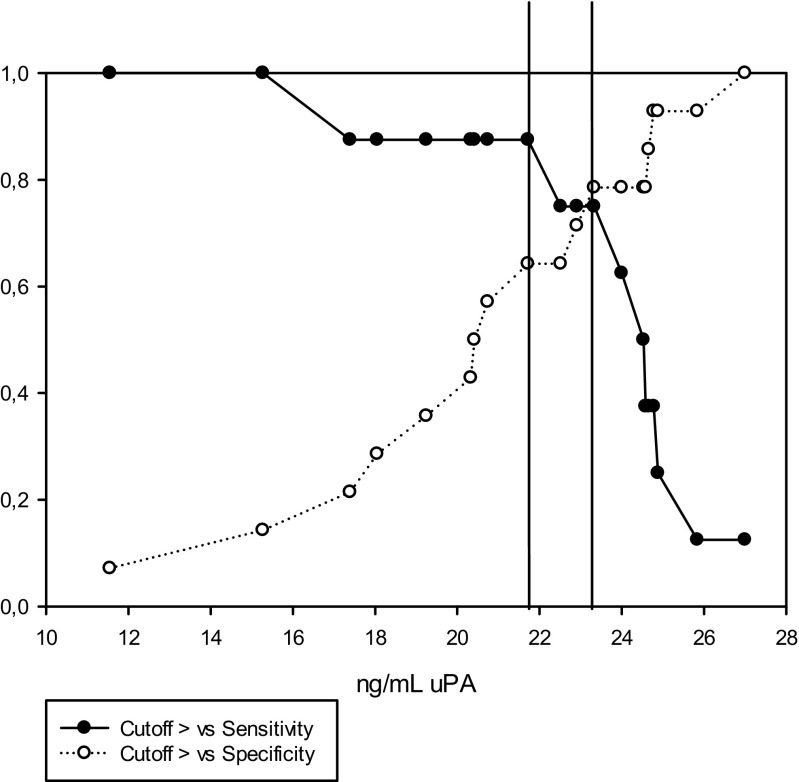

We next examined how uPA concentrations in seminal plasma and spermatozoa correlated to assisted reproduction outcomes following AIH and ICSI (Tables 5, 6, and 7). Higher values for total uPA in seminal plasma were detected (24.91 ± 0.98 vs. 20.26 ± 1.05 ng/mL, P = 0.01; Table 5) in cases that resulted in pregnancy compared to those that did not. No differences were found for the other uPA measurements (P = 0.38 and P = 0.43, respectively; Table 5). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was applied to evaluate the predictive value of the uPA concentration in seminal plasma and spermatozoa for fertility (pregnancy rate, %). The area under the curve was 0.72 for total uPa in seminal plasma (P < 0.05; Fig. 2) and 0.56 for active uPA in seminal plasma and uPA in spermatozoa. However, the later values were not significant (P > 0.05). According to the contingency table of sensitivity and “1 − specificity”, the optimal cutoff value for predicting pregnancy using the uPA concentration in seminal plasma was 21.6 ng/mL. With this value, the sensitivity was 93% and specificity was 51%, with values for positive and negative likelihood ratios LR + =1.91 and LR− = 0.14 (Fig. 3).

Table 5.

uPA concentration in seminal plasma and spermatozoa in samples grouped according to pregnancy or not after all the ART treatments

| Total uPA seminal plasma | Active uPA seminal plasma | Total uPA spermatozoa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No pregnancy | 20.26 ± 1.05 (37)* | 1.41 ± 0.16 (75) | 1.24 ± 0.27 (42) |

| Pregnancy | 24.91 ± 0.98 (14)* | 1.67 ± 0.27 (34) | 0.71 ± 0.18 (7) |

| P value | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.43 |

*P < 0.05

Table 6.

uPA concentration in seminal plasma and spermatozoa in samples grouped according pregnancy or not after AIH treatment

| Total uPA seminal plasma | Active uPA seminal plasma | Total uPA spermatozoa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No pregnancy | 20.41 ± 1.53 (23)* | 1.17 ± 0.18 (52) | 1.33 ± 0.31 (36) |

| Pregnancy | 26.66 ± 1.61 (6)* | 1.22 ± 0.27 (12) | 0.72 ± 0.26 (4) |

| P value | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.54 |

*P < 0.05

Table 7.

uPA concentration in seminal plasma and spermatozoa in samples grouped according to pregnancy or not after ICSI treatment

| Total uPA seminal plasma | Active uPA seminal plasma | Total uPA spermatozoa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No pregnancy | 20.01 ± 1.23 (14) | 1.96 ± 0.30 (23) | 0.71 ± 0.21 (6) |

| Pregnancy | 23.60 ± 1.07 (8) | 1.92 ± 0.39 (22) | 0.71 ± 0.30 (3) |

| P value | 0.05 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for total uPA concentration in seminal plasma (SP) (ng/mL) and pregnancy outcomes after application of ART treatments (AIH or ICSI)

Fig. 3.

Cutoff value, sensitivity, and specificity for uPA content in seminal plasma for predicting pregnancy after application of ART treatments (AIH or ICSI), n = 51. Optimal cutoff value 21.6 ng/mL

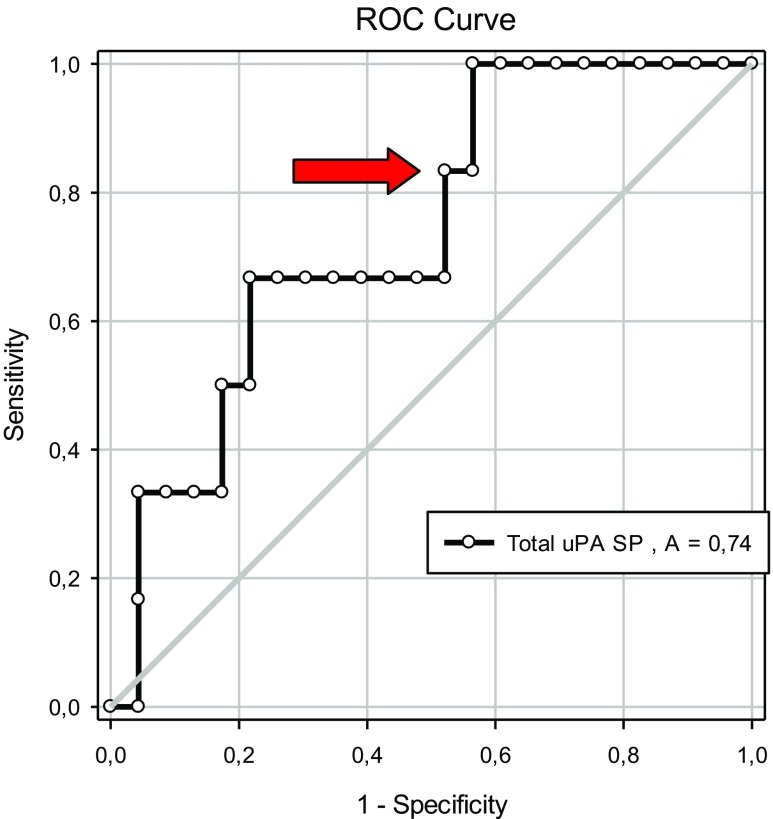

Using only the data derived from AIH cycles, higher values for total uPA in seminal plasma were detected in the cases resulting in pregnancy compared to those that did not (26.66 ± 1.61 vs. 20.41 ± 1.53 ng/mL; P = 0.02; Table 6). No differences were found for the other uPA measurements (P > 0.05; Table 6). ROC curve analysis was applied to evaluate the predictive value of the uPA concentration in seminal plasma on fertility (pregnancy rate, %). The area under the curve was 0.74, and the optimal cutoff value for predicting pregnancy using the uPA concentration in seminal plasma was 22.6 ng/mL (P < 0.05; Fig. 4). With this value, the sensitivity was 83% and the specificity was 48%, LR+ = 1.60 and LR− = 0.35 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for total uPA concentration in seminal plasma (SP) (ng/mL) and pregnancy outcomes after application of AIH treatment

Fig. 5.

Cutoff value, sensitivity, and specificity for uPA content in seminal plasma for predicting pregnancy after application of AIH treatment (n = 29). Optimal cutoff value 22.6 ng/mL

Using only the data derived from ICSI cycles, we detected higher values of total uPA in seminal plasma in cases with pregnancy (23.60 ± 1.07 ng/mL) compared to no pregnancy 20.01 ± 1.23 ng/mL) (P = 0.05; Table 7). No differences were found for the other uPA measurements (P > 0.05; Table 6). The area under the curve for total uPA in seminal plasma was 0.75 (P < 0.05; Fig. 6). Two possible cutoff values were determined for predicting pregnancy by the use of uPA concentration in seminal plasma: 23.3 ng/mL (sensitivity 75% and specificity 79%, LR+ 3.50 and LR− 0.32) and 21.7 ng/mL (sensitivity 88% and specificity 64%, LR+ 2.45 and LR− 0.19; Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for uPA concentration in seminal plasma (ng/mL) and pregnancy after ICSI treatment

Fig. 7.

Cutoff value, sensitivity, and specificity for uPA content in seminal plasma for predicting pregnancy after application of ICSI treatment (n = 22)

Discussion

The main conclusions from this study are that the concentrations of active uPA in seminal plasma is a sign or index of good sperm quality, however without prognostic value of fertility outcomes. Furthermore, total uPA content in seminal plasma is not related to sperm parameters but it is positive related to fertility after AIH and ICSI treatment. On the other hand, the presence of uPA in spermatozoa is a sign of bad quality and is not related to fertility .

Seminal plasma levels of uPA are much higher than in blood plasma [11, 29]. uPA is present in human testicular tissue [4], and some authors have suggested that the uPA present in seminal plasma is secreted by the accessory glands [27], with a significant contribution from prostatic secretions [11, 29]. Also, uPA is synthesized in epithelial cells of the epididymal caudal region, vas deferens, and seminal vesicles [5, 30].

The total uPA seminal plasma values in this study are similar to some studies in the range of 15.5–32 ng/mL [11, 26–28, 32] but higher than others [25] (see Table 1). These differences could be related to the use of different methodologies of measurement (RIA vs. ELISA) and the different efficiencies of the antibodies used. Also, sampling methodology could have an effect on results. Previously, it has been reported that the use of extrinsic inhibitors, as 1,10-phenanthroline and PPACK, could modify the measurements [11]. In addition, the first fraction of the ejaculate (prostatic fluid rich fraction) presented higher uPA content in seminal plasma than the second fraction, with a rich proportion of the secretion coming from seminal vesicles [11, 29]. According to these authors, uPA levels are associated more with prostatic secretions than those from seminal vesicles.

According to our results, total uPA in seminal plasma does not influence the quality of the ejaculate and the sperm parameters. No differences were found in total uPA concentration in seminal plasma between normozoospermic and non-normozoospermic cases (Table 4). These results are consistent with previous studies that did not find differences [25–28]. Only one study reported higher values of uPA in seminal plasma in normozoospermic (n = 36) compared to azoospermic samples which had a limited sample size of 2 [29]. No correlation was found between total uPA in seminal plasma with sperm parameters (Table 3) as previously reported [25, 26]. Recently, a study of cell free mRNA of uPA content in seminal plasma by qRT-PCR demonstrated no differences between normozoospermic individuals and asthenozoospermic patients [33].

The normal amount of uPA antigen but low enzymatic activity in normal seminal plasma indicated that uPA activity was under appropriate control [32]. In this study, the active uPA represented less than 10% of the total uPA in most of the cases. In this same sense, some authors reported that 93% of uPA content in the seminal plasma is linked to protein C inhibitor (PCI), so it is an inactive form [11, 34]. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the concentrations of active uPA have been reported. Although the values of active uPA were not different between normo and non-normospermic samples, they were positively related to sperm parameters (volume, motility and no spermatozoa in ejaculate; Table 3). PAA associated to uPA activity (IU/mL) has previously been measured in seminal plasma [32, 35]. Higher levels of uPA activity (20 ± 60-fold higher than control) were observed in a couple of infertile patients, where the inhibitory capacity of the protein C inhibitor (PCI) was abnormally decreased [32]. There is no other information about the possible relationship between active uPA or uPA activity and seminal parameters.

uPA concentration in spermatozoa (ng/106 spermatozoa) was lower in normozoospermic samples than oligo and oligoasthenoteratozoospermic (OAT) samples, with very similar values as previously reported when normozoospermic and OAT samples were compared (1.6 ± 0.2 (n = 15) vs. 7.7 ± 2.1 (n = 41), P < 0.05) [27]. In this study, uPA concentration in spermatozoa (ng/106 spermatozoa) was inversely related with the sperm quality parameters (concentration, motility, and morphology). No other studies have previously evaluated this relationship in human samples. However, our group has detected an inverse relationship between uPA content in pig spermatozoa and such parameters as motility and normal acrosome morphology (data not published).

The only study that directly related the plasminogen activator activity (both uPA and tPA together) in sperm cells with IVF outcome showed higher values of plasminogen activation in successful IVF cases than failure cases. However, the methodology used was not able to distinguish the role of uPA, tPA, and PA inhibitors in this relationship with fertilization rate [36]. Knock out animal models, specifically in the mouse, could be helpful in clarifying the specific plasminogen-plasmin system component involved in this effect. In fact, although it was shown years ago that single- and double-knockout uPA and tPA male and female mice could reproduce, double knockout animals were less fertile than controls [37]. Despite this interesting data, no deeper studies have been carried out subsequently, so the specific reproductive events affected in these animals or the PAs responsible remain unknown.

Improvement of fertility after AIH could be directly related to the activation in the seminal plasma of latent transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) induced by uPA, tPA, and other factors of the plasminogen-plasmin system [38]. TGF-β1 is one of the most important immunosuppressive factors present in seminal plasma [39]. However, it is difficult to understand how uPA in seminal plasma can directly improve the fertility after embryo transfer of ICSI produced embryos, without any direct connection to sperm quality. So, an indirect relationship must be implied, probably related to the interaction between a rich uPA seminal plasma and uPA receptors (uPAR) in spermatozoa, cumulus cells, and oocytes during their contact in the IVF dish. As for the ICSI situation, binding of seminal plasma uPA to uPAR in the oocyte would not be plausible, so the carrying of uPA by the fertilizing spermatozoa would be an indirect option to be explored further. In this sense, some studies offer some understanding of the role of uPA on sperm fertilizing ability in domestic animal models like pigs [14–16]. Addition of uPA to human samples has improved motility parameters [24], and uPA could be a chemotactic factor as in the mouse model [23].

On the other hand, total uPA in seminal plasma has been suggested to have a fibrinolytic activity [29] and the soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) has been reported in seminal plasma [40]. Interestingly, suPAR values in seminal plasma are inversely related to sperm motility and vitality, and it was used as predictor of male accessory gland inflammation [40]. A recent study comparing seminal parameters, suPAR values in seminal plasma and accessory gland inflammation in psoriasis patients and healthy subjects confirmed this relationship [41]. Finally, a relationship between high viscosity of seminal plasma, high values of pro-inflammatory interleukins, and male accessory gland inflammation has been reported [42]. It will be necessary to study the possible roles of uPA in the modulation of seminal plasma viscosity associated with inflammation of accessory glands or the use of uPA measurement as an indicator of subclinical process of inflammation.

This first study opens the possibility to explore in deep the role of all the activators, inhibitors, and receptors of the plasminogen/plasmin system present in seminal plasma and spermatozoa on the fertility after artificial reproductive treatments.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Prof. Bill Holt (University of Sheffield) and Prof. Francesca Duncan (Northwestern University) for their critical reviews of the manuscript and English improvement.

Funding

The study was funded by the Centre for Development of Industrial Technology (CDTI, Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness) with FEDER funds (IDI-20120531) and 20040/GERM/16 from Fundación Séneca de la Región de Murcia.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was conducted with institutional approval from Instituto Valenciano de Infertilidad (Ref. 1210-MU-109JM). Couples undergoing assisted reproduction treatment in Instituto Valenciano de Infertilidad (IVI-Murcia, Spain) and sperm donors were included after signing the informed consent.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Preliminary results have been presented to 31st Annual Meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), Lisbon (Portugal), June 14–17, 2015 and 33rd European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology Annual Meeting, Geneva (Switzerland), July2–5, 2017.

References

- 1.Castellino FJ, Ploplis VA. Structure and function of the plasminogen/plasmin system. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93(4):647–654. doi: 10.1160/TH04-12-0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aisina RB, Mukhametova LI. Structure and function of plasminogen/plasmin system. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2014;40(6):590–605. doi: 10.1134/S1068162014060028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espana F, Gilabert J, Estelles A, Romeu A, Aznar J, Cabo A. Functionally active protein C inhibitor/plasminogen activator inhibitor-3 (PCI/PAI-3) is secreted in seminal vesicles, occurs at high concentrations in human seminal plasma and complexes with prostate-specific antigen. Thromb Res. 1991;64(3):309–320. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(91)90002-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunnarsson M, Lecander I, Abrahamsson PA. Factors of the plasminogen activator system in human testis, as demonstrated by in-situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5(10):934–940. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.10.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang T, Guo CX, Hu ZY, Liu YX. Localization of plasminogen activator and inhibitor, LH and androgen receptors and inhibin subunits in monkey epididymis. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3(11):945–952. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.11.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang T, Zhou HM, Liu YX. Expression of plasminogen activator and inhibitor, urokinase receptor and inhibin subunits in rhesus monkey testes. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3(3):223–231. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suominen J, Eliasson R, Niemi M. The relation of the proteolytic activity of human seminal plasma to various semen characteristics. J Reprod Fertil. 1971;27(1):153–156. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0270153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Propping D, Zaneveld LJ, Tauber PF, Schumacher GF. Purification of plasminogen activators from human seminal plasma. Biochem J. 1978;171(2):435–444. doi: 10.1042/bj1710435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Astedt B, Wallén P, Aasted B. Occurrence of both urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator in human seminal plasma. Thromb Res. 1979;16(3–4):463–472. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(79)90093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liedholm P, Astedt B. Fibrinolytic inhibitors in human seminal plasma. Experientia. 1974;30(10):1113–1114. doi: 10.1007/BF01923638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espana F, Estelles A, Fernandez PJ, Gilabert J, Sanchez-Cuenca J, Griffin JH. Evidence for the regulation of urokinase and tissue type plasminogen activators by the serpin, protein C inhibitor, in semen and blood plasma. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70(6):989–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu YX. Involvement of plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in spermatogenesis, sperm capacitation, and fertilization. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2007;33(1):29–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Magueresse-Battistoni B. Serine proteases and serine protease inhibitors in testicular physiology: the plasminogen activation system. Reproduction. 2007;134(6):721–729. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coy P, Jimenez-Movilla M, Garcia-Vazquez FA, Mondejar I, Grullon L, Romar R. Oocytes use the plasminogen-plasmin system to remove supernumerary spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(7):1985–1993. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grullon LA, Gadea J, Mondejar I, Matas C, Romar R, Coy P. How is plasminogen/plasmin system contributing to regulate sperm entry into the oocyte? Reprod Sci. 2013;20(9):1075–1082. doi: 10.1177/1933719112473657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mondejar I, Grullon LA, Garcia-Vazquez FA, Romar R, Coy P. Fertilization outcome could be regulated by binding of oviductal plasminogen to oocytes and by releasing of plasminogen activators during interplay between gametes. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(2):453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrer MJ, Xu W, Shetty J, Herr J, Oko R. Plasminogen improves mouse IVF by interactions with inner acrosomal membrane-bound MMP2 and SAMP14. Biol Reprod. 2016;94(4):88. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.133496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin Y, Han Y, Xiong CL, Li HG, Hu L, Zhang L. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator: a new target for male contraception? Asian J Androl. 2015;17(2):269–273. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.143316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao K, Liu Y, Xiong Z, Hu L, Xiong C-l. Tissue-specific inhibition of urokinase-type plasminogen activator expression in the testes of mice by inducible lentiviral RNA interference causes male infertility. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2017. 10.1071/rd16477. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Taitzoglou I, Kokolis N, Smokovitis A. Release of plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor from spermatozoa of man, bull, ram and boar during acrosome reaction. Mol Androl. 1996;8:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taitzoglou IA, Chapman DA, Killian GJ. Induction of the acrosome reaction in bull spermatozoa with plasmin. Andrologia. 2003;35(2):112–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0272.2003.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taitzoglou IA, Chapman DA, Zervos IA, Killian GJ. Effect of plasmin on movement characteristics of ejaculated bull spermatozoa. Theriogenology. 2004;62(3–4):553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding X, Li H, Xiong C. Chemotactic effect of urokinase-type plasminogen activator on mouse spermatozoa in vitro. Front Med China. 2008;2(2):195–199. doi: 10.1007/s11684-008-0037-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong CY, Chiang BN, Huang JJ, Wu P. Two plasminogen activators, streptokinase and urokinase, stimulate human sperm motility. Andrologia. 1985;17(4):317–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1985.tb01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnaud A, Schved JF, Gris JC, Costa P, Navratil H, Humeau C. Tissue-type plasminogen activator level is decreased in human seminal plasma with abnormal liquefaction. Fertil Steril. 1994;61(4):741–745. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)56655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebisch IM, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Sweep FC, Zielhuis GA, Geurts-Moespot A, Thomas CM. Possible role of the plasminogen activation system in human subfertility. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(3):619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maier U, Kirchheimer JC, Hienert G, Christ G, Binder BR. Fibrinolytic parameters in spermatozoas and seminal plasma. J Urol. 1991;146(3):906–908. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)37958-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Dreden P, Audrey C, Aurelie R. Human seminal plasma fibrinolytic activity. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2007;33(1):21–28. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Dreden P, Gonzales J, Poirot C. Human seminal fibrinolytic activity: specific determinations of tissue plasminogen activator and urokinase. Andrologia. 1991;23(1):29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1991.tb02488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huarte J, Belin D, Bosco D, Sappino AP, Vassalli JD. Plasminogen activator and mouse spermatozoa: urokinase synthesis in the male genital tract and binding of the enzyme to the sperm cell surface. J Cell Biol. 1987;104(5):1281–1289. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen, 5th ed. Geneva, World Health Organization; 2010.

- 32.He S, Lin YL, Liu YX. Functionally inactive protein C inhibitor in seminal plasma may be associated with infertility. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5(6):513–519. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.6.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian Y, Li L, Zhang F, Xu J. Seminal plasma HSPA2 mRNA content is associated with semen quality. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33(8):1079–1084. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0730-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Espana F, Navarro S, Medina P, Zorio E, Estelles A. The role of protein C inhibitor in human reproduction. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2007;33(1):41–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smokovitis A, Kokolis N, Alexopoulos C, Alexaki E, Eleftheriou E. Plasminogen activator activity, plasminogen activator inhibition and plasmin inhibition in spermatozoa and seminal plasma of man and various animal species—effect of plasmin on sperm motility. Fibrinolysis. 1987;1(4):253–257. doi: 10.1016/0268-9499(87)90045-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lison D, Tas S, Gennart JP, Psalti I, De Cooman S, Lauwerys R. Plasminogen activator activity and fertilizing ability of human spermatozoa. Int J Androl. 1993;16(3):201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1993.tb01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carmeliet P, Schoonjans L, Kieckens L, Ream B, Degen J, Bronson R, et al. Physiological consequences of loss of plasminogen activator gene function in mice. Nature. 1994;368(6470):419–424. doi: 10.1038/368419a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu TM, Kawinski E. Plasmin, substilisin-like endoproteases, tissue plasminogen activator, and urokinase plasminogen activator are involved in activation of latent TGF-beta 1 in human seminal plasma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253(1):128–134. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ochsenkuhn R, O’Connor AE, Hirst JJ, Gordon Baker HW, de Kretser DM, Hedger MP. The relationship between immunosuppressive activity and immunoregulatory cytokines in seminal plasma: influence of sperm autoimmunity and seminal leukocytes. J Reprod Immunol. 2006;71(1):57–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Autilio C, Morelli R, Milardi D, Grande G, Marana R, Pontecorvi A, et al. Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor as a putative marker of male accessory gland inflammation. Andrology. 2015;3(6):1054–1061. doi: 10.1111/andr.12084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caldarola G, Milardi D, Grande G, Quercia A, Baroni S, Morelli R, et al. Untreated psoriasis impairs male fertility: a case-control study. Dermatology. 2017. 10.1159/000471849. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Castiglione R, Salemi M, Vicari LO, Vicari E. Relationship of semen hyperviscosity with IL-6, TNF-alpha, IL-10 and ROS production in seminal plasma of infertile patients with prostatitis and prostato-vesiculitis. Andrologia. 2014;46(10):1148–1155. doi: 10.1111/and.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]