Abstract

Organic acids play a key role in the troposphere, contributing to atmospheric aqueous-phase chemistry, aerosol formation, and precipitation acidity. Atmospheric models currently account for less than half the observed, globally averaged formic acid loading. Here we report that acetaldehyde photo-tautomerizes to vinyl alcohol under atmospherically relevant pressures of nitrogen, in the actinic wavelength range, λ = 300–330 nm, with measured quantum yields of 2–25%. Recent theoretical kinetics studies show hydroxyl-initiated oxidation of vinyl alcohol produces formic acid. Adding these pathways to an atmospheric chemistry box model (Master Chemical Mechanism) demonstrates increased formic acid concentrations by a factor of ~1.7 in the polluted troposphere and a factor of ~3 under pristine conditions. Incorporating this mechanism into the GEOS-Chem 3D global chemical transport model reveals an estimated 7% contribution to worldwide formic acid production, with up to 60% of the total modeled formic acid production over oceans arising from photo-tautomerization.

The concentration of formic acid in Earth’s atmosphere is under-predicted by atmospheric models. Here the authors show that acetaldehyde photo-tautomerizes to vinyl alcohol under tropospheric conditions, with subsequent oxidation via OH radicals supplying up to 60% of total modeled formic acid production over oceans.

Introduction

Organic acids are ubiquitous in Earth’s atmosphere and are detected in urban, rural, polar, tropical, and marine environments. They are present in the gas phase, and in clouds and aerosols where they substantially impact rainwater acidity1,2 and aqueous-phase chemistry. The high oxygen content of organic acids dramatically reduces volatility compared to less oxidized molecules of similar molar mass and the larger organic acids are believed to be key species in the nucleation and growth of atmospheric particles3–6, which have significant impacts on human health, local pollution, and global climate7.

Over the last decade, improved measurement techniques8,9 have repeatedly shown significantly higher organic acid concentrations than predicted by atmospheric models10. This disagreement, which is particularly marked in the daytime, implies missing or underestimated photochemical source terms, or overestimated organic acid sinks. The smallest organic acids, formic (HCOOH, FA) and acetic (CH3COOH, AA) acid, dominate global tropospheric organic acids, comprising >60% of free acidity in pristine rainwater and >30% in polluted areas10. Although fossil fuel combustion emits organic acids directly, 14C/12C isotope ratios show atmospheric HCOOH is mainly modern carbon, with fossil fuel sources making only minor contributions11. The majority of atmospheric organic acids are believed to be produced via photochemical oxidation of biogenic and anthropogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The largest global source of FA is thought to be photochemical production, though the magnitude of this is highly uncertain10. Plants emit FA directly12 but also reabsorb it, complicating determinations of the net effect, although Schobesberger et al. report recently that forests might be a net source13. Forest fires14,15 and photochemical oxidation of organic aerosols16 have also been proposed as important sources of FA. A recent study10 noted FA concentrations in Earth’s boundary layer of several parts per billion, which are 2–3 times larger than predicted from currently known production and consumption pathways. They concluded that photochemical biogenic sources are dominant but currently underestimated, and that there must be widespread sources of FA from a variety of precursor species.

One potential source of FA is the photo-tautomerization of acetaldehyde (CH3CHO, AC) to its enol form, vinyl alcohol (CH2=CHOH, VA). Archibald et al.17 first suggested that enols, emitted directly from combustion sources, would oxidize in the atmosphere to produce organic acids. Andrews18 subsequently postulated, based on isotopic scrambling studies of AC, that even larger sources of atmospheric enols could arise from sunlight-driven tautomerization of carbonyl compounds. Clubb19 provided the first experimental evidence of AC → VA photo-tautomerization, albeit for neat AC at low pressure under non-atmospheric conditions. Da Silva20 then used electronic structure and master equation calculations to conclude that oxidation of VA by the hydroxyl radical (OH) is a fast reaction that produces mainly FA. Given this background, Millet10 evaluated the global importance of the keto-enol photo-tautomerization hypothesis, and concluded that this new AC photo-tautomerization mechanism constitutes ~15% of global FA sources, but suggested its impact is limited because FA itself catalyzes the reverse tautomerization, VA → AC, effectively buffering its own production21. However, Peeters22 found the rate of gas-phase reverse tautomerization to be six orders of magnitude slower than the value reported by da Silva21, which was used previously by Millet et al.10, and concluded that gas-phase reverse tautomerization was unimportant in the atmosphere22.

In this contribution, we report direct experimental evidence under atmospheric conditions that AC does indeed photo-tautomerize to VA. We provide pressure- and wavelength-dependent quantum yields for VA production in up to 1 atm of N2 in the actinic wavelength range of λ = 300–330 nm. To evaluate the impact on FA sources, we implement photo-tautomerization, VA oxidation, and acid-catalyzed gas-phase reverse tautomerization into two atmospheric models: (i) a detailed chemistry box model which uses the Master Chemical Mechanism23, and (ii) the GEOS-Chem 3D chemical transport model (CTM)24. These simulations allow us to determine, on a global basis, that the photo-tautomerization mechanism contributes an estimated 7% to worldwide formic acid production, and up to 60% of the total modeled formic acid production over oceans.

Results

Experimental

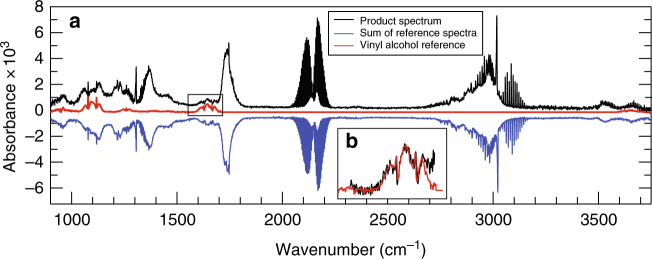

Acetaldehyde (AC) at a pressure of 1–10 Torr, mixed with 0–750 Torr of N2, was placed in a static Teflon-coated gas cell. The mixture was irradiated with a tunable, pulsed laser at wavelengths in the actinic UV range of λ = 300–330 nm (AC does not absorb significantly for λ > 330 nm). We detected primary and secondary photochemical products and the depletion of the precursor using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Sequential infrared spectra were averaged in 30 s periods before, during, and after 7 min of UV irradiation. Figure 1 shows a representative spectrum following 315 nm irradiation at 760 Torr total pressure. The signal due to unreacted AC has been subtracted to yield a spectrum solely due to photochemical reaction products. The amount of subtracted signal provides directly the concentration of AC that has been photolyzed (1–4% across various experiments).

Fig. 1.

Fourier transform infrared spectra of the photolysis products. a Infrared spectrum (black) following 7 min of 315 nm irradiation of a mixture of 10 Torr acetaldehyde in 750 Torr nitrogen. The remaining acetaldehyde has been subtracted from the spectrum. The inverted blue trace shows the sum of scaled reference spectra of photochemical products. The red trace is an infrared reference spectrum of vinyl alcohol, a portion of which, between 1550 and 1700 cm–1, is expanded in the inset b

We identify and quantify photolysis products by fitting a library of reference spectra, calibrated and measured on the same apparatus, to the spectrum obtained after photolysis of AC. An example of such a fit is shown in Fig. 1 (blue curve). All detected compounds are stable, formed either as direct products of AC irradiation (CO and CH4), or from secondary reaction of primary radical products with each other or the parent AC. Vinyl alcohol (VA) is assigned unambiguously by its characteristic spectral features19, most prominent near 1100, 1650, and 3650 cm−1, as shown in the red reference spectrum in Fig. 1. Other than VA, all other identified products are consistent with the known photochemistry of AC.

The assignments and fitting of reference spectra of all species are described in more detail in Supplementary Note 1. Typical reference spectra used throughout are shown in Supp. Fig. 1. The mass yields (mass of products formed/mass of CH3CHO lost) are plotted in Supp. Fig. 2, showing they are close to unity throughout, except at 330 nm. At this wavelength there are unassigned features (Supp. Fig. 3), indicating at least one unidentified product at long wavelengths. Generally, however, we have accounted for all the products from irradiation of AC. All products are stable with respect to time, except for VA itself, which undergoes a wall-catalyzed reverse tautomerization to AC. We record the time-dependence of VA pressure and compensate for this loss as explained in Supp. Note 1 and Supp. Fig. 4.

The quantum yield (QY) of each product was calculated from the known UV absorption cross-section of AC25 and the measured photon flux, as described in Methods and Supp. Fig. 5. An example calculation is shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Attributing each observed product to a primary photolysis event allows us to determine the primary quantum yields for AC irradiation as a function of wavelength and pressure.

The primary photochemistry of AC has been studied in detail because of its importance in atmospheric pathways25,26, its role as a prototypical carbonyl27–29, and as a target for studies of fundamental new reaction mechanisms30–32. There are three primary bond-breaking processes that feature in the near ultraviolet photochemistry of AC:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

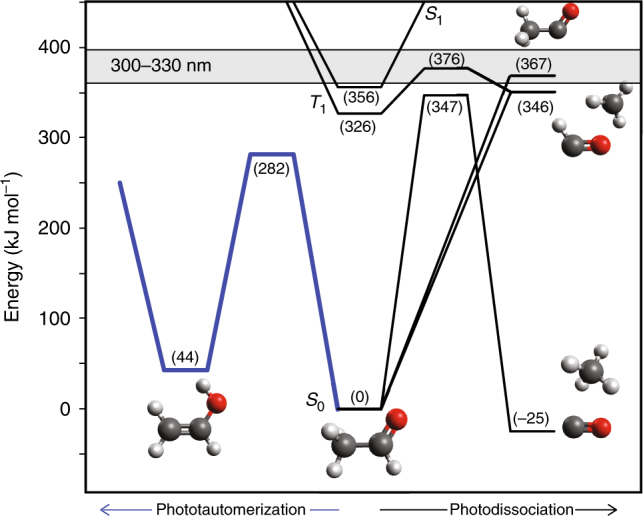

These are shown schematically in Fig. 2, where energies of stable species were obtained from Active Thermochemical Tables33, excited state energies from spectroscopic studies34,35, and transition state energies from ab initio calculations36,37. Absorption of a UV photon in the actinic range excites AC to the lowest lying excited singlet state, S1, which is bound at these energies. Intersystem crossing (ISC) rapidly populates the lowest triplet state, T1, where the lowest energy photochemical pathway produces CH3 + HCO (Eq. (1)) when λ < 318.5 nm28,38. At longer wavelength (λ > 318.5 nm), a barrier on the T1 surface prevents dissociation, and AC eventually reaches the ground electronic state, S0, by sequential ISC (S1 → T1 → S0). Although it is often assumed that internal conversion is responsible for transfer to S0 in AC, both recent experiments39 and theoretical evidence40 suggest S1/S0 conical intersections are too high in energy to provide a valid pathway at actinic UV energies.

Fig. 2.

Simplified potential energy diagram. Stationary points describing photochemical pathways of acetaldehyde following excitation at actinic wavelengths of 300–330 nm (gray band). Energies obtained from refs. 33–37, isomerization of acetaldehyde to vinyl alcohol indicated in blue

On S0, there are a number of primary photodissociation processes, including Eqs (1) – (3) above. In addition, AC can readily isomerize prior to dissociation, as evidenced by observation of H/D exchange in photoproducts of selectively deuterated AC18,37. The intermediate isomers can be stabilized by collision with a “bath gas”, M. Of particular importance, the keto-enol tautomerization barrier lies well below the photon energy (see Fig. 2) and below any other isomerization barrier. The enol isomer of CH3CHO, CH2=CHOH, is therefore the most likely isomerization product:

| 4 |

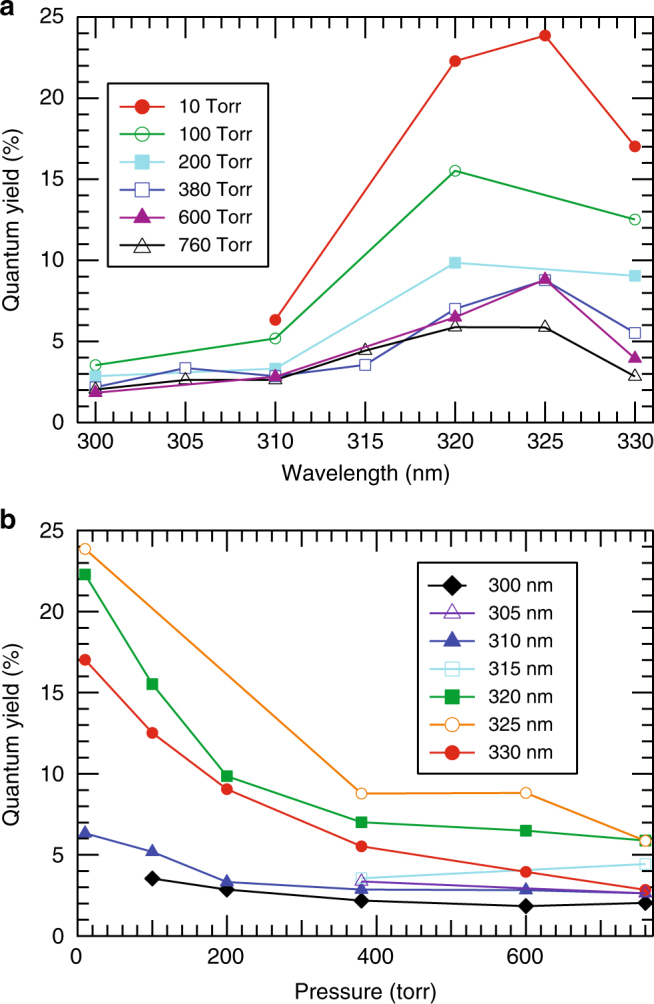

Experimental QYs for VA formation are shown in Fig. 3, and display significant variation with N2 pressure and excitation wavelength. At shorter wavelengths (λ < 318.5 nm) the T1 pathway to HCO + CH3 dominates (shown in Fig. 2) and the photo-tautomerization QY is small (Fig. 3). Collisions compete with photodissociation at higher pressures, removing internal energy until the molecule has insufficient energy to surmount the T1 barrier. The total photodissociation QY therefore drops with increasing N2 pressure and decreasing photolysis energy. As described in more detail in Supp. Note 1, our results are in good agreement with previous work25,26, as shown in Supp. Fig. 6. The QY for VA production, however, generally increases as photolysis energy decreases, with a steeper rise once the kinetically favored dissociation on the T1 surface becomes energetically inaccessible (Fig. 3). Like the total photodissociation QY, the QY for VA production decreases with increasing pressure, as AC is collisionally quenched below the S0 barrier to tautomerization.

Fig. 3.

Quantum yields of vinyl alcohol. Quantum yields for vinyl alcohol production as a function of a wavelength and b pressure at room temperature. Uncertainty ±25% of the stated value

Atmospheric modeling

In the troposphere, da Silva calculated that OH will add to either end of the enol C=C double bond with negative activation energy21:

| 5a |

| 5b |

where formation of the α-substituted product (Eq. (5a)) is favored. These radicals react rapidly with O2, forming peroxy radicals:

| 6a |

| 6b |

The peroxy radical from (Eq. (6a)) undergoes a 1,5 H-shift followed by decomposition to OH + CH2O + HCOOH, whereas the radical from (Eq. (6b)) dissociates to gylcolaldehyde:

| 7a |

| 7b |

To test the importance of AC photo-tautomerization in the atmosphere, we need to consider both the detailed atmospheric chemistry, as well as global transport mechanisms. We have used a complementary approach, incorporating the quantum yields measured in this work (Fig. 3), along with Eqs (5a)–(7b), into two atmospheric models: a zero-dimensional atmospheric chemistry box model utilizing the Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM) version 3.223, and a global chemical transport model (GEOS-Chem 3D CTM)24. The first is state-of-the-art in terms of chemical complexity, but as a box model lacks transport effects and regional or global context. The second provides fully resolved transport and global context but as a global model cannot be as chemically explicit.

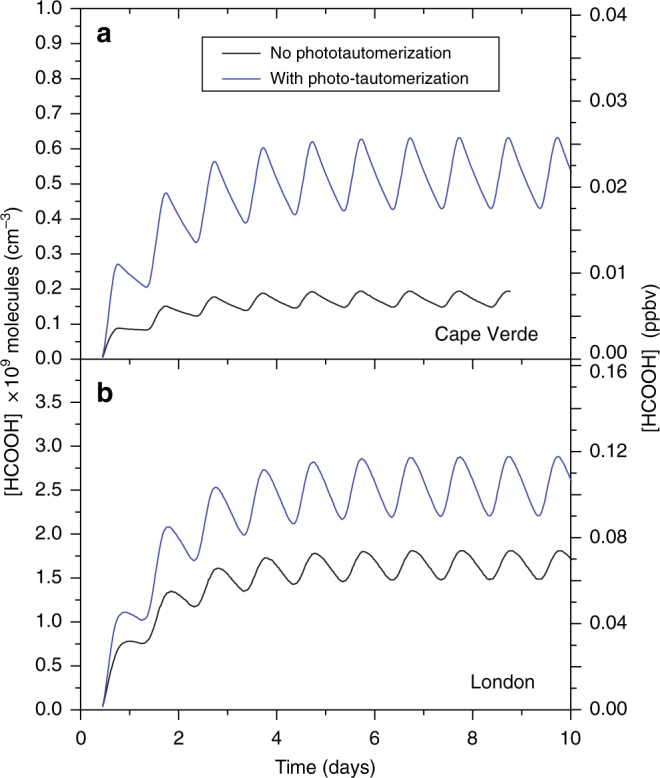

Two MCM box model simulations were run to test the importance of photo-tautomerization in clean and polluted regions of the atmosphere. The first simulation was constrained with gas-phase data, including observed AC mixing ratios, photolysis rates, and meteorological parameters from the 2007 RHaMBLe project at the Cape Verde Atmospheric Observatory41. The second simulation was constrained with field data from the summer 2012 ClearfLo project42 that took place at an urban background site in London. At Cape Verde, HCOOH was detected with a reported median value of 128 pptv43; in London concentrations were much higher, with a peak concentration of 6.7 ppbv44.

In both simulations, the time-dependent photo-tautomerization rate was calculated by integrating the product of the AC absorption cross-section45, the 760 Torr experimental quantum yield (this work) and the time-dependent photon flux as a function of wavelength. We used da Silva’s total rate coefficient for pathway 5a + 6a of 3.8×10−11 cm3 molecule−1 s−1 21.

We also investigated the impact of the recently reported acid-catalyzed gas-phase reverse tautomerization of VA back to AC. Two additional simulations were run with the two acid-catalyzed gas-phase reverse tautomerization rate coefficients (i) 1.3×10−14 cm3 molecule−1 s−1 at 298 K as used in ref. 21 or (ii) 2.0×10−20 cm3 molecule−1 s−1 as reported in ref. 22. Using the larger rate coefficient for gas-phase reverse tautomerization, the modeled FA concentrations were reduced by ~6% in both clean and polluted model scenarios whereas the smaller rate coefficient had no observed effect; that is, we conclude gas-phase reverse tautomerization had no observed effect on FA yields.

The application of the MCM to clean air and polluted conditions is shown in Fig. 4, with and without the photo-tautomerization mechanism. Including photo-tautomerization in the MCM gives a factor of ~1.7 increase in FA in London, and a factor of ~3 increase in Cape Verde, showing that this mechanism represents a major change relative to the known photochemical sources of FA in these environments. However, we also see in Fig. 4 that it is still not enough to explain the observed concentration of FA in these two locations. The MCM box model considers only photochemical sources of FA, while omitting direct emissions and any transport effects that may also contribute to the observed concentrations. We therefore apply the GEOS-Chem 3D global CTM to assess the global impact of the photo-tautomerization mechanism in a manner that accounts for not only the photochemical production and loss of FA, but also non-photochemical sources, transport, and deposition.

Fig. 4.

Master Chemical Mechanism simulations. Master Chemical Mechanism box model simulations of formic acid production with (blue) and without (black) photo-tautomerization and OH + vinyl alcohol reactions. Two distinct atmospheric conditions are shown: a pristine, ocean environment at Cape Verde, Sao Vincente Island, and b urban environment at London, UK

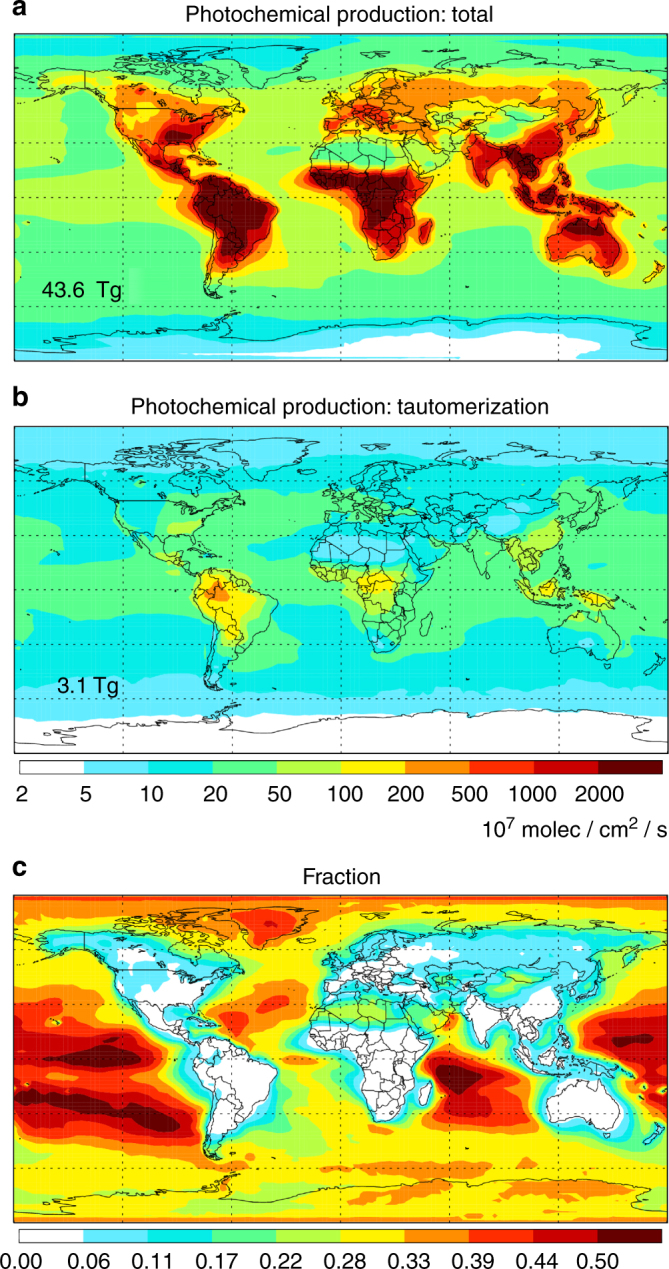

Figure 5 shows the column-integrated FA production rates from photo-tautomerization and from all photochemical sources combined as simulated by GEOS-Chem (Supp. Fig. 7 shows and Supplementary Note 2 discusses the results separately for the lower- and free-troposphere). Previous application of the GEOS-Chem 3D model used a single estimated photo-tautomerization quantum yield and an overestimate of the gas-phase reverse tautomerization rate coefficient10. Here we use our experimental pressure- and wavelength-dependent quantum yields and more realistic rate coefficients to better estimate the importance of the photo-tautomerization of AC. Using this data, we predict the photo-tautomerization pathway produces 3.1 Tg/y of FA, approximately 7% of the total simulated photochemical sources. As shown in Fig. 5, the fractional contribution of photo-tautomerization to FA production is highest over remote areas and is the dominant model source over many ocean regions. For example, Fig. 5(c) reveals that photo-tautomerization accounts for 40–60% of the column-integrated photochemical FA production in GEOS-Chem over a large part of the global oceans. FA and other carboxylic acids have long been known to be ubiquitous in the remote marine boundary layer, with uncertain origin1,46, where they can affect aqueous-phase SIV oxidation on marine aerosols47. The simulations here show that marine emissions of AC and its precursors16,48 dominate the modeled FA production in such regions. Conversely, the relative contribution of photo-tautomerization to FA production is small over continental regions where isoprene and other terrestrially emitted VOCs dominate as FA sources.

Fig. 5.

Column-integrated formic acid (FA) production rates as simulated by the GEOS-Chem 3D chemical transport model as a function of latitude and longitude. a Total FA production from all chemical pathways. b FA produced via photo-tautomerization of AC. c Fraction of total FA produced via photo-tautomerization

Although photo-tautomerization of AC does provide a source of FA, it alone cannot account for the factor of two or more discrepancy seen between experimental and modeled FA concentrations worldwide10,16. However, the role of photo-tautomerization of other carbonyls has not been explored. For example, the known photochemistry of propanal49,50 and acetone51–53 is broadly similar to AC, with similar tautomerization barrier heights54. We might therefore expect photo-tautomerization efficiencies to be broadly similar in these carbonyls under atmospheric conditions. There are also a large number of short and branched chain carbonyls in the atmosphere although larger carbonyls, such as butanal55, have other photochemical pathways, e.g. the Norrish Type II mechanism which also yields enols. The relative rates and quantum yields of these processes, in comparison to tautomerization, are unknown; tautomerization kinetics should be evaluated to characterize possible formation mechanisms of larger organic acids.

Although more work on sources and sinks of enols in the atmosphere is warranted, the present results argue strongly that photo-tautomerization of carbonyl molecules plays a key role in organic acid production in Earth’s atmosphere that must be included in quantitative models.

Methods

Laser photolysis Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Pre-mixed acetaldehyde vapor and N2 gas were flowed into a Teflon-coated stainless steel gas cell using two calibrated mass flow control valves (MKS). The total pressure was measured using a calibrated capacitance manometer (MKS). The partial pressure of AC was confirmed in situ by recording an FTIR spectrum before photolysis and comparing to a reference spectrum. Gas mixtures were prepared in the range 1–20 Torr neat AC, and 10 or 20 Torr AC mixed with approximately 50, 100, 200, 380, 600, and 750 Torr N2.

The static gas mix was irradiated at wavelengths between 300 and 330 nm by the frequency doubled output of an OPO, pumped by a Nd:YAG laser. Typical laser energy was 3–6 mJ pulse−1. The laser beam was reflected through the cell four times. Laser energy was measured for each pass of the laser using an energy meter. These measurements, when taken with an empty cell, provided the losses for each optical component (mirrors and windows). When AC was admitted to the cell, the output laser energy dropped due to absorption of the laser radiation by AC, from which the number of photons absorbed can be derived. From the known path length and pressure of acetaldehyde, the absorption cross-section was calculated, which was in good agreement (±10%) with the literature value25.

FTIR spectra at 1 cm−1 resolution were recorded before photolysis and continuously during irradiation for 5–7 min. Spectra were saved every 30 s. FTIR spectra were recorded for an additional 5–7 min after laser irradiation was halted. The time profile of all stable products showed a linear rise in absorption with irradiation time, followed by constant absorption after irradiation ceased. VA, however, showed a non-linear rise in absorption, followed by a decay in intensity for up to 15 min, as shown in Supplementary Note 1, Supp. Figure 4. Measurement of the decay time provided the wall reaction rate and convolving with a linear rise provided the rate of production and hence the QY in absence of wall reactions. Measurements were acquired over three laboratory sessions and repeat measurements were acquired both within and between sessions. Reproducibility between the resulting spectra was very good, yielding an estimated uncertainty in the final quantum yields of ±25%.

Atmospheric modeling

The GEOS-Chem 3D model runs employed meteorological data from the GEOS-5 Forward Processing (GEOS-FP) Atmospheric Data Assimilation System, which have a native resolution of 0.25° latitude×0.3125° longitude and 72 vertical levels. For the present analysis we degraded the resolution to 2°×2.5° with 47 vertical levels and used a 15-min transport time step and 1-year model spinup. The model includes detailed HOx-NOx-VOC-O3-aerosol tropospheric chemistry, air-sea exchange, and deposition (wet + dry), with extensive updates for the simulation of FA as described in ref. 10. Further model details relevant to the simulations shown here (emissions, other chemical pathways leading to FA) are provided by Millet et al.10.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request; see author contributions for specific data sets.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

M.F.S., M.J.T.J., and S.H.K. acknowledge the Australian Research Council for support (DP130104326 and DP160101792). M.F.S. acknowledges the award of an Australian APA award in support of her PhD studies. L.K.W. and D.E.H. acknowledge the National Centre for Atmospheric Science, which is a distributed institute funded by the Natural Environment Research Council. B.S. acknowledges support of the National Science Foundation (NSF; CHE-1266407) and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Visiting Faculty Program. D.B.M. acknowledges support from NSF (AGS-1148951), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA; NNX14AP89G), and the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute. D.L.O. acknowledges support from the U.S. DOE, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, which also funded all the experimental apparatus in this work. Sandia National Laboratories is a multimission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC., a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International, Inc., for the U.S. DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-NA0003525.

Author contributions

The laser photolysis FT-IR experiments were carried out by M.F.S., B.S., and S.H.K., in the laboratory of D.L.O. Analysis of this data was done by M.F.S., M.J.T.J., D.L.O., and S.H.K. Atmospheric modeling was performed by L.K.W., D.E.H., and D.B.M. The first draft of the manuscript was written by D.L.O. and S.H.K. All authors revised the manuscript. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Energy or the United States Government.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-04824-2.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

David L. Osborn, Email: dlosbor@sandia.gov

Scott H. Kable, Email: s.kable@unsw.edu.au

References

- 1.Keene WC, Galloway JN. The biogenic cycling of formic acids and acetic acids through the troposphere: an overview of current understanding. Tellus. 1988;40B:322–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0889.1988.tb00106.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stavrakou T, et al. Satellite evidence for a large source of formic acid from boreal and tropical forests. Nat. Geosci. 2012;5:26–30. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavouras IG, Mihalopoulos N, Stephanou EG. Formation of atmospheric particles from organic acids produced by forests. Nature. 1998;395:683–686. doi: 10.1038/27179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang R, et al. Atmospheric new particle formation enhanced by organic acids. Science. 2004;304:1487–1490. doi: 10.1126/science.1095139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianchi F, et al. New particle formation in the free troposphere: a question of chemistry and timing. Science. 2016;352:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tröstl J, et al. The role of low-volatility organic compounds in initial particle growth in the atmosphere. Nature. 2016;533:527–531. doi: 10.1038/nature18271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finlayson-Pitts BJ, Pitts JN., Jr. Chemistry of the Upper and Lower Atmosphere. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cady-Pereira KE, et al. HCOOH measurements from space: TES retrieval algorithm and observed global distribution. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014;7:2297–2311. doi: 10.5194/amt-7-2297-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan B, et al. Investigation of secondary formation of formic acid: urban environment vs. oil and gas producing region. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15:1975–1993. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-1975-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millet DB, et al. A large and ubiquitous source of atmospheric formic acid. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15:6283–2015. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-6283-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasius M, et al. Sources to formic acid studied by carbon isotopic analysis and air mass characterization. Atmos. Environ. 2000;34:2471–2479. doi: 10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00416-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kesselmeier J, Bode K, Gerlach C, Jork EM. Exchange of atmospheric formic acid and acetic acids with trees and crop plants under controlled chamber and purified air conditions. Atmos. Environ. 1998;32:1765–1775. doi: 10.1016/S1352-2310(97)00465-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schobesberger S, et al. High upward fluxes of formic acid from a boreal forest canopy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016;43:9342–9351. doi: 10.1002/2016GL069599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.R’Honi Y, et al. Exceptional emissions of NH3 and HCOOH in the 2010 Russian wildfires. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013;13:4171–4181. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-4171-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaliyakunnel S, Millet DB, Wells KC, Cady-Pereira KE, Shephard MW. A large underestimate of formic acid from tropical fires: constraints from space-borne measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:5631–5640. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b06385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paulot F, et al. Importance of secondary sources in the atmospheric budgets of formic and acetic acids. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:1989–2013. doi: 10.5194/acp-11-1989-2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Archibald AT, McGillen MR, Taatjes CA, Percival CJ, Shallcross DE. Atmospheric transformation of enols: a potential secondary source of carboxylic acids in the urban troposphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007;34:L21801. doi: 10.1029/2007GL031032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrews DU, et al. Photo-tautomerization of acetaldehyde to vinyl alcohol: a potential route to tropospheric acids. Science. 2012;337:1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.1220712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clubb AE, Jordan MJT, Kable SH, Osborn DL. Photo-tautomerization of acetaldehyde to vinyl alcohol is a primary process in UV-irradiated acetaldehyde. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:3522–3526. doi: 10.1021/jz301701x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.So S, Wille U, da Silva G. Atmospheric chemistry of enols: a theoretical study of the vinyl alcohol + OH + O2 reaction mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:6694–6701. doi: 10.1021/es500319q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.da Silva G. Carboxylic acid catalyzed keto-enol tautomerizations in the gas phase. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:7523–7525. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peeters J, Nguyen VS, Müller JF. Atmospheric vinyl alcohol to acetaldehyde tautomerization revisited. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:4005–4011. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone D, Whalley LK, Heard DE. Tropospheric OH and HO2 radicals: field measurements and model comparisons. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:6348–6404. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35140d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bey I, et al. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology- Model description and evaluation. J. Geophys. Res. 2001;106:23073–23095. doi: 10.1029/2001JD000807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moortgat GK, Meyrahn H, Warneck P. Photolysis of acetaldehyde in air: CH4, CO and CO2 quantum yields. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2010;11:3896–3908. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horowitz A, Calvert JG. Wavelength dependence of the primary processes in acetaldehyde photolysis. J. Phys. Chem. 1982;86:3105–3114. doi: 10.1021/j100213a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gherman BF, Friesner RA, Wong TH, Min Z, Bersohn R. Photodissociation of acetaldehyde: the CH4 + CO channel. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:6128–6133. doi: 10.1063/1.1355983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amaral GA, Arregui A, Rubio-Lago L, Rodríguez JD, Bañares L. Imaging the radical channel in acetaldehyde photodissociation: competing mechanisms at energies close to the triplet exit barrier. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;133:064303. doi: 10.1063/1.3474993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morajkar P, Bossolasco A, Schoemaecker C, Fittschen C. Photolysis of CH3CHO at 248 nm: evidence of triple fragmentation from primary quantum yield of CH3 and HCO radicals and H atoms. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;140:214308. doi: 10.1063/1.4878668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houston PL, Kable SH. Photodissociation of acetaldehyde as a second example of the roaming mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16079–16082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604441103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heazlewood BR, et al. Roaming is the dominant mechanism for molecular products in acetaldehyde photodissociation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:12719–12724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802769105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee KLL, et al. Two roaming pathways in the photolysis of CH3CHO between 328 and 308 nm. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:4633–4638. doi: 10.1039/C4SC02266A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruscic, B. Active Thermochemical Tables (ATcT) values based on Version 1.118 of the Thermochemical Network. Argonne National Laboratory https://ATcT.anl.gov (2015).

- 34.Baba M, Hanazaki I, Nagashima U. The S1 (n, π*) state of acetaldehyde and acetone in supersonic nozzle beam: methyl internal rotation and C=O out-of-plane wagging. J. Chem. Phys. 1985;82:3938–3947. doi: 10.1063/1.448886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, et al. The T1 (n, π*) ← S0 laser induced phosphorescence excitation spectrum of acetaldehyde in a supersonic free jet: torsion and wagging potentials in the lowest triplet state. J. Chem. Phys. 1996;105:2547–2552. doi: 10.1063/1.472120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harding LB, Georgievskii Y, Klippenstein SJ. Roaming radical kinetics in the decomposition of acetaldehyde. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2010;114:765–777. doi: 10.1021/jp906919w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heazlewood BR, et al. Near-threshold H/D exchange in CD3CHO photodissociation. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:443–448. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heazlewood BR, Rowling SJ, Maccarone AT, Jordan MJT, Kable SH. Photochemical formation of HCO and CH3 on the ground S0 (1A′) state of CH3CHO. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;130:054310. doi: 10.1063/1.3070517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toulson BW, Kapnas KM, Fishman DA, Murray C. Competing pathways in the near-UV photochemistry of acetaldehyde. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:14276–14288. doi: 10.1039/C7CP02573D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen S, Fang WH. Insights into photodissociation dynamics of acetaldehyde from ab initio calculations and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;131:054306. doi: 10.1063/1.3196176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whalley LK, et al. The chemistry of OH and HO2 radicals in the boundary layer over the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010;10:1555–1576. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-1555-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bohnenstengel SI, et al. Meterology, air quality and health in London. B. Am. Meter. Soc. 2015;96:779–804. doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00245.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sander R, et al. Gas phase acid, ammonia and aerosol ionic and trace element concentrations at Cape Verde during the reactive halogens in the marine boundary layer (RHaMBLe) 2007 intensive sampling period. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2013;5:385–392. doi: 10.5194/essd-5-385-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bannan TJ, et al. Importance of direct anthropogenic emissions of HC(O)OH measured by a chemical ionisation mass spectrometer (CIMS) during the winter ClearfLo campaign in London, January 2012. Atmos. Environ. 2014;83:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.10.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez RD, Buitrago AA, Howell NW, Hearn CH, Jones JA. The near UV absorption spectra of several aliphatic aldehydes and ketones. Atmos. Environ. 1992;26A:785–792. doi: 10.1016/0960-1686(92)90238-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baboukas ED, Kanakidou M, Mihalopoulos N. Carboxylic acids in gas and particuate phase above the Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 2000;105:14459–14471. doi: 10.1029/1999JD900977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Erickson DJ, Seuzaret C, Keene WC, Gong SL. A general circulation model based calculation of HCl and ClNO2 production from sea salt dechlorination: reactive Chlorine Emissions Inventory. J. Geophys. Res. 1999;104:8347–8372. doi: 10.1029/98JD01384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millet DB, et al. Global atmospheric budget of acetaldehyde: 3D model analysis and constraints from in-situ and satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010;10:3405–3425. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-3405-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Y, Zhu L. The wavelength dependence of the photodissociation of propionaldehyde in the 280–330 nm region. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:9689–9696. doi: 10.1021/jp011445s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Metha GF, Terentis AC, Kable SH. Near threshold photochemistry of propanal. Barrier height, transition state structure, and product state distributions for the HCO channel. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106:5817–5827. doi: 10.1021/jp025590x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gierczak T, Burkholder JB, Bauerle S, Ravishankara AR. Photochemistry of acetone under tropospheric conditions. Chem. Phys. 1998;231:229–244. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0104(98)00006-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blitz MA, Heard DE, Pilling MJ, Arnold SR, Chipperfield MP. Pressure and temperature-dependent quantum yields for the photodissociation of acetone between 279 and 327.5 nm. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004;31:L06111. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haas Y. Photochemical α-cleavage of ketones: revisiting acetone. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2004;3:6–16. doi: 10.1039/B307997J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elango M, Maciel GS, Palazzetti F, Lombardi A, Aquilanti V. Quantum chemistry of C3H6O molecules: structure and stability, isomerization pathways, and chirality changing mechanisms. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2010;114:9864–9874. doi: 10.1021/jp1034618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tadić J, Juranić I, Moortgat GK. Pressure dependence of the photo-oxidation of selected carbonyl compounds in air: n-butanal and n-pentanal. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2001;143:169–179. doi: 10.1016/S1010-6030(01)00524-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request; see author contributions for specific data sets.