Abstract

INTRODUCTION: The coexpression of pIGF-1R and MMP-7 (double-positive phenotype, DP) correlates with poor overall survival (OS) in KRAS wild-type (WT) (exon 2) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients treated with irinotecan-cetuximab in second/third line. METHODS: We analyzed two prospective biomarker design trials of newly diagnosed RAS-WT mCRC patients treated with panitumumab-FOLFOX6 (PULSE trial; NCT01288339) or cetuximab plus either FOLFOX6/FOLFIRI (POSIBA trial; NCT01276379). The main exposure was DP phenotype (DP/non-DP), as assessed by two independent pathologists. DP cases were defined by immunohistochemistry as >70% expression of moderate or strong intensity for both MMP-7 and pIGF-1R. Primary endpoint: progression-free survival (PFS); secondary endpoints: OS and response rate. PFS and OS were adjusted by baseline characteristics using multivariate Cox models. RESULTS: We analyzed 67 patients (30 non-DP, 37 DP) in the PULSE trial and 181 patients in the POSIBA trial (158 non-DP, 23 DP). Response rates and PFS were similar between groups in both studies. DP was associated with prolonged OS in PULSE (adjusted HR: 0.23; 95%CI: 0.11-0.52; P=.0004) and with shorter OS in POSIBA (adjusted HR: 1.67; 95%CI: 0.96-2.90; P=.07). CONCLUSION: A differential effect of anti-EGFRs on survival by DP phenotype was observed. Panitumumab might be more beneficial for RAS-WT mCRC patients with DP phenotype, whereas cetuximab might improve OS in non-DP.

Introduction

The doublets of FOLFIRI or FOLFOX plus cetuximab or panitumumab are effective as first-line therapies for patients with RAS wild-type (WT) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) [1], [2], [3]. However, certain patients do not fully benefit from these EGFR-targeted antibodies, requiring additional biomarkers to tailor their use.

The type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R) is a transmembrane glycoprotein composed of two extracellular and two cytoplasmic subunits acting as a receptor-tyrosine kinase [4], [5], [6], [7]. IGF-1R is activated in colorectal cancer, mediating key processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis resistance, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [8]. The signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is also constitutively activated in colorectal cancer [9] by growth factor receptors (EGFR and IGF-1R) through AKT/mTORC/RAC1 [10], or induced by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) through IL-6-JAK1/2 [11], [12]. Regardless of this intrinsic or extrinsic activation, STAT3 signaling enforces matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7) expression [13].

Recently, IGF-II was shown to activate IGF-1R and STAT3 more effectively than IGF-I and to induce SLUG transcriptional activity and EMT in CRC [14]. Feedback activation has been also demonstrated between MMP-7 and IGF-1R. MMP-7 plays a crucial role in IGF-I and IGF-II bioavailability through the insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) degradation [15], [16], [17], which in turn mediates IGF-1R–dependent [18] but also IGF-1R–independent NF-kB activation [19]. The blockade of IGF-1R is also involved in the suppression of cancer cell invasion through downregulation of MMP-7 [20]. Therefore, IGF-1R and MMP-7 contribute by multiple pathways to activate the two more critical transcription factors: STAT3 and NF-kB.

Our group has previously shown that coexpression of p-IGF-1R and MMP-7 (double positivity phenotype, DP) correlates with poor prognosis in KRAS WT (exon 2) patients treated with irinotecan plus cetuximab as second-/third-line therapy [21]. To validate these findings, we designed two prospective, translational trials in K-RAS (exon-2) WT mCRC patients treated with panitumumab plus FOLFOX6 (PULSE trial) or cetuximab plus either FOLFOX6 or FOLFIRI (POSIBA trial) as a first line of therapy, with the shared objective of evaluating the prognostic role of DP in this patient population.

Methods

Trials Design

Patients were eligible in both studies if they were ≥18 years old; had histologically confirmed KRAS WT (exon 2) mCRC with ≥1 radiologically measurable lesion; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) of 0-1; and adequate hepatic, renal, and bone marrow functions. Patients were ineligible if they were pregnant, had a history of treatment with anti-EGFR or chemotherapy (with the exception of adjuvant therapy), or had undergone surgery of metastatic disease.

The PULSE (GEMCAD 09-03, clinicaltrials.gov id: NCT01288339) and POSIBA (GEMCAD 10-02, clinicaltrials.gov id: NCT01276379) were both single-arm prospective biomarker design trials. Patients were recruited into the PULSE trial from November 2010 to April 2013 in 24 Spanish centers and treated with FOLFOX6 plus panitumumab (6 mg/kg). Patients were recruited into the POSIBA trial from July 2011 to May 2015 in 28 Spanish centers and treated with FOLFOX6 or FOLFIRI (at investigator’s choice) plus biweekly cetuximab (500 mg/m2). In both trials, cytotoxic drugs were administered for 6 months, followed by anti-EGFR monotherapy until progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity.

Patients were classified as DP if their tumor presented moderate or strong intensity (++/+++) and >70% expression for both MMP-7 and pIGF-1R by immunohistochemistry staining (see below). The primary endpoint for both studies was progression-free survival (PFS), defined as time from enrollment to disease progression, death, or end of follow-up, whichever came first. Secondary objectives included response rate, toxicity profile, and overall survival (OS), defined as time from enrollment to death or end of follow-up. Disease status was evaluated with abdominopelvic CT scan every 2 months in the PULSE trial and every 3 months in the POSIBA trial until progressive disease. Patients without a second CT evaluation were not assessable for response rate. Patients who underwent liver resection were not censored at the time of surgical resection and were followed until progressive disease.

The safety population comprised all patients who received at least one dose of study treatment. Adverse events (AEs) were recorded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0. The PULSE and POSIBA trials were approved by local institutional review boards and ethics committees in accordance with national and international guidelines; all patients signed a written informed consent before study entry.

RAS and BRAF Mutational Analysis

Mutational analysis of genomic DNA of KRAS (exon 2) was performed by direct sequencing. In the PULSE trial, it was evaluated centrally at the Hospital Clínic (Barcelona, Spain), although analysis at the referring Center was also allowed. In the POSIBA trial, it was evaluated at the referring center. Extended RAS mutational analysis (including KRAS/NRAS exons 2, 3 and 4) started on 10/2013 in the PULSE trial and on 10/2015 in the POSIBA trial after protocol amendments. The BRAF V600E mutation (exon 15) was genotyped by allelic discrimination in genomic DNA using TaqMan technology (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

We used hematoxylin and eosin staining to evaluate the presence and classification of the tumor specimens. Consecutive 2- to 3-μm–thick sections were used for IHC. Removal of paraffin and heat incubation in citrate (pH=6.0) were performed to achieve antigen retrieval. The primary p-IGF-1R antibody (anti-pY1316, provided by Dr. Rubini) was used at 1:100 dilution. MMP-7 (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN) was used at 1:1500 dilution. The expression was cytoplasmatic. Detection was performed using the Dako EnVision K4011 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). In the PULSE trial, IHC evaluation was done centrally in Hospital Clínic (Barcelona, Spain), and results were given before patient inclusion to balance the number of patients in both arms. In the POSIBA trial, IHC evaluation was performed after patients’ inclusion. Thus, DP distribution represents that of the source population.

Statistical Analysis

In the PULSE trial, a recruitment of 78 patients was planned to have an 80% power to detect a difference in median PFS of 6 months between DP and non-DP patients (assuming a bilateral α error of 0.05 and the occurrence of 56 events). A screening of 270 patients was planned because only 25% of patients were expected to be DP and 40% to be KRAS mutant. Recruitment continued until both exposure groups (DP and non-DP) were filled in a 1:1 ratio. In the POSIBA trial, a recruitment of 170 RAS WT patients (after ammendent of all RAS WT analysis) was planned to detect, with a 80% of power and a bilateral alpha of 5%, a 20% difference in 12-month PFS. We assumed that the 12-month PFS of the non-DP patiens would be of 60%, and a 25% of DP patients in the source population.

Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to plot unadjusted survival curves. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to perform adjusted analyses for PFS and OS. Multivariate analysis was built deciding a priori the variables to adjust for: age, sex, p-IGF-1R/MMP-7 expression, primary tumor location, stage at diagnosis, surgery of primary tumor, number of involved organs, type of involved organ, liver-only extension, ECOG-PS, BRAF mutational status, administered therapy, and baseline levels of: leucocytes, hemoglobin, platelets, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Additionally, we performed sensitivity analyses with automated stepwise selection of variables (P value for variable entry into the model=.2, P value to stay in the model=.1) and by entering in the model those variables with a P<.1 in the univariate analysis. All the P values are two-sided. Analyses were implemented using SAS V9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

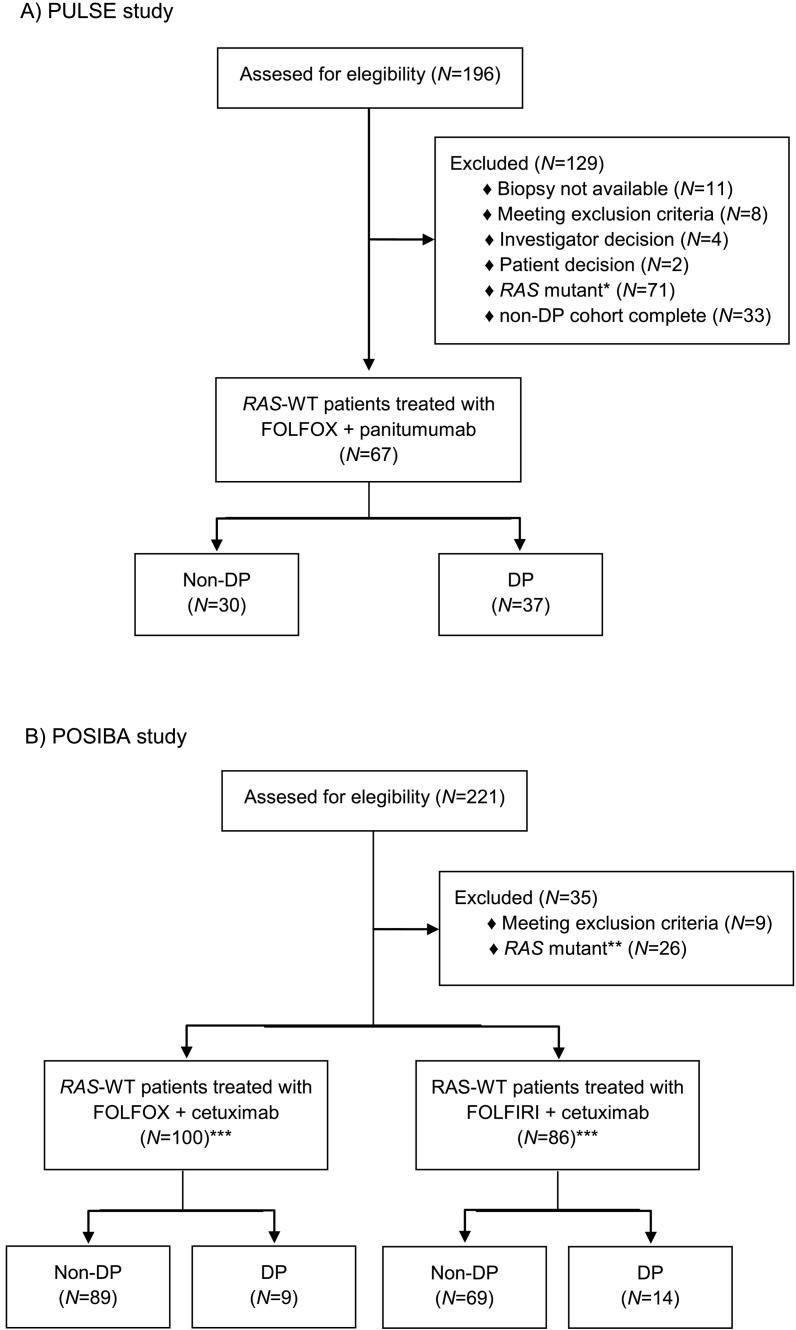

A total of 67 (PULSE) and 181 (POSIBA) RAS-WT mCRC patients were included in the analysis (Figure 1). In the PULSE trial, 30 patients were non-DP and 37 patients were DP, whereas in the POSIBA trial, 158 patients were non-DP and 23 patients were DP. Patients were followed for a median of 27 months in the PULSE trial and for a median of 26 months in the POSIBA trial. DP patients in the POSIBA trial were less likely to have PS 0 and lung metastasis and also have lower levels of hemoglobin than non-DP patients. There were no relevant differences in the baseline characteritics of both groups in the PULSE trial (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Patients’ disposition in the (A) PULSE and (B) POSIBA trials.

*RAS mutant includes mutations in KRAS (exon 2) (N=60), and KRAS mutations (exons 3 and 4) and NRAS mutations (exons 2, 3, and 4) (N=11).

**RAS mutant includes mutations in KRAS (exons 3 and 4) and NRAS mutations (exons 2, 3, and 4).

***The expression of p-IGF-1R and MMP-7 was not evaluable in five patients: two treated with FOLFOX+cetuximumab and three with FOLFIRI+cetuximab

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Trial and Double Positivity

| POSIBA |

PULSE |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-DP (N=158) | DP (N=23) | P Value⁎ | Non-DP (N=30) | DP (N=37) | P Value⁎ | |

| BRAF mutated, N (%) | 16 (10) | 4 (17) | .29 | 2 (7) | 5 (14) | .45 |

| Female, N (%) | 46 (29) | 7 (30) | .99 | 12 (40) | 10 (27) | .30 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 62 (11) | 67 (7) | .031 | 63 (8) | 64 (8) | .61 |

| Primary tumor location, N (%) | .98 | .47 | ||||

| Ascending colon | 28 (18) | 4 (17) | 2 (7) | 3 (8) | ||

| Transverse colon | 13 (8) | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | 5 (14) | ||

| Descending colon | 12 (8) | 2 (9) | 3 (10) | 3 (8) | ||

| Sigma | 65 (41) | 11 (48) | 15 (50) | 12 (32) | ||

| Rectum | 40 (25) | 5 (22) | 9 (30) | 14 (38) | ||

| Stage (at diagnosis), N (%) | .77 | .88 | ||||

| I | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| II | 12 (8) | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | ||

| III | 32 (20) | 3 (13) | 5 (17) | 4 (11) | ||

| IV | 113 (72) | 19 (83) | 24 (80) | 31 (84) | ||

| Surgery of primary tumor, N (%) | 89 (56) | 12 (52) | .82 | 20 (67) | 24 (65) | .99 |

| ECOG-PS, N (%) | .012 | .61 | ||||

| 0 | 110 (70) | 9 (39) | 16 (53) | 22 (59) | ||

| 1 | 45 (28) | 14 (61) | 13 (43) | 15 (41) | ||

| 2 | 3 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | ||

| Number of metastatic organs, N (%) | .30 | .33 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5) | ||

| 1 | 79 (50) | 15 (65) | 13 (43) | 16 (43) | ||

| >2 | 79 (50) | 8 (35) | 17 (57) | 19 (51) | ||

| Liver metastasis, N (%) | .87 | .93 | ||||

| No liver metastasis | 35 (22) | 5 (22) | 7 (23) | 10 (27) | ||

| <=3, <=5 cm | 28 (18) | 5 (22) | 3 (10) | 4 (11) | ||

| >3 or >5 cm | 95 (60) | 13 (57) | 20 (67) | 23 (62) | ||

| Node metastasis, N (%) | 50 (32) | 7 (30) | .99 | 9 (30) | 12 (32) | .99 |

| Lung metastasis, N (%) | 48 (30) | 2 (9) | .043 | 11 (37) | 14 (38) | .99 |

| Peritoneal metastasis, N (%) | 23 (15) | 4 (17) | .75 | 9 (30.0) | 8 (22) | .57 |

| Administered therapy, N (%) | .18 | |||||

| FOLFOX+cetuximab | 89 (56) | 9 (39) | NA | NA | ||

| FOLFIRI+cetuximab | 69 (44) | 14 (61) | NA | NA | ||

| FOLFOX+panitumumab | NA | NA | 30 (100) | 37 (100) | ||

| Leucocytes, mean (SD) | 8.3 (3.3) | 8.9 (3.7) | .39 | 9.8 (7.1) | 8.2 (2.5) | .23 |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD) | 13.8 (9.2) | 11.9 (1.6) | .023 | 12.9 (1.7) | 12.4 (1.5) | .15 |

| Platelets, mean (SD) | 282 (104) | 298 (140) | .60 | 298 (144) | 296 (120) | .96 |

| ALP, mean (SD) | 148 (122) | 179 (177) | .44 | 166 (208) | 219 (237) | .34 |

| LDH, mean (SD) | 465 (457) | 632 (1246) | .56 | 683 (814) | 446 (415) | .16 |

| CEA, mean (SD) | 267 (732) | 708 (1772) | .26 | 502 (1212) | 838 (3609) | .61 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; DP, double positivity; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; SD, standard deviation.

Fisher’s exact test

Efficacy According to DP Status

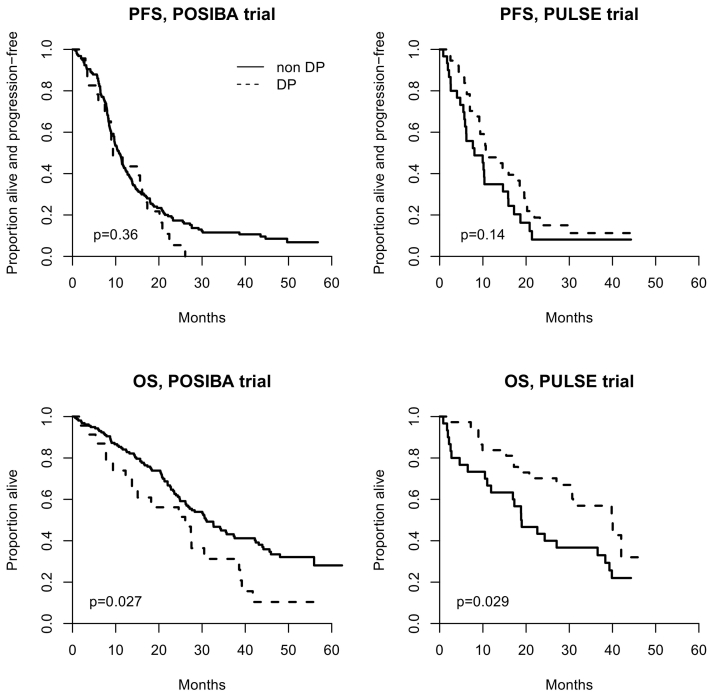

Median PFS (95% CI) was 11.2 months (9.2-18.5) for DP patients and 8.0 months (5.5-14.7) for non-DP patients in the PULSE trial (P=.14). Median PFS (95% CI) was 9.4 months (7.5-16.1) for DP patients and 10.8 months (9.5-12.2) for non-DP patients in the POSIBA trial (P=.36, Figure 2). Adjusted HR for PFS was 0.33 (0.17-0.66) in the PULSE trial and 1.39 (0.84-2.31) in the POSIBA trial (Table 2). Sensitivity analysis did not change results substantially (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival and overall survival according to DP status in the (A) PULSE and (B) POSIBA trial.

Table 2.

Progression-Free Survival; Cox Regression Analysis

| POSIBA |

PULSE |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| DP | 1.24 (0.79-1.94) | .36 | 1.39 (0.84-2.31) | .20 | 0.68 (0.40-1.14) | .14 | 0.33 (0.17-0.66) | .0017 |

| ECOG-PS >0 | 2.02 (1.46-2.79) | <.0001 | 1.77 (1.24-2.54) | .0017 | 1.19 (0.70-2.02) | .52 | 1.33 (0.71-2.509) | .37 |

| Age >65 years | 1.18 (0.87-1.61) | .30 | 0.99 (0.69-1.42) | .97 | 1.43 (1.85-2.41) | .18 | 1.65 (0.79-3.43) | .18 |

| BRAF mutated | 2.33 (1.44-3.79) | .0006 | 2.09 (1.16-3.77) | .014 | 1.77 (0.75-4.17) | .19 | 1.77 (0.34-9.03) | .49 |

| Surgery of primary tumor | 1.62 (1.19-2.22) | .0024 | 1.60 (1.12-2.28) | .0099 | 0.56 (0.32-0.98) | .041 | 0.45 (0.22-0.94) | .034 |

| Left-sided primary tumor | 1.02 (0.74-1.39) | .92 | 0.92 (0.63-1.32) | .64 | 0.65 (0.33-1.30) | .22 | 0.41 (0.14-1.18) | .10 |

| CEA (logarithmic term) | 0.55 (0.39-0.78) | .0008 | 0.55 (0.37-0.81) | .0029 | 1.10 (0.97-1.25) | .13 | 1.04 (0.88-1.23) | .65 |

| LDH (logarithmic term) | 1.03 (0.96-1.10) | .40 | 1.03 (0.94-1.14) | .49 | 1.14 (0.78-1.67) | .49 | 1.65 (0.98-2.77) | .058 |

| Liver metastasis | 1.04 (0.82-1.31) | .74 | 1.02 (0.78-1.33) | .88 | ||||

| 0 | Ref. | |||||||

| <=3, <=5 cm | Ref. | 0.99 (0.38-2.63) | .99 | 0.83 (0.24-2.84) | .76 | |||

| >3 or >5 cm | 0.63 (0.38-1.03) | .065 | 0.95 (0.54-1.69) | .87 | 1.11 (0.59-2.09) | .74 | 0.86 (0.35-2.01) | .74 |

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CI, confidence interval; DP, double positivity; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; WT, wild-type.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analyses for Progression-Free Survival; Cox Regression Analysis

| POSIBA |

PULSE |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate S1 |

Multivariate S2 |

Multivariate S1 |

Multivariate S2 |

|||||

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| DP | 1.13 (0.71-1.81) | .61 | 1.13 (0.71-1.81) | .61 | 0.59 (0.35-1.02) | .058 | 0.35 (0.18-0.67) | .0015 |

| ECOG-PS >0 | 1.75 (1.25-2.45) | .0011 | 1.75 (1.25-2.45) | .0011 | ||||

| Age >65 years | ||||||||

| BRAF mutated | 2.04 (1.24-3.34) | .0048 | 2.04 (1.24-3.34) | .0048 | ||||

| Surgery of primary tumor | 1.43 (1.04-1.97) | .029 | 1.43 (1.04-1.97) | .029 | 0.50 (0.28-0.88) | .017 | 0.45 (0.22-0.90) | .023 |

| Left-sided primary tumor | 0.35 (0.15-0.83) | .0165 | ||||||

| CEA (logarithmic term) | 0.58 (0.41-0.84) | .0032 | 0.58 (0.41-0.84) | .0032 | ||||

| LDH (logarithmic term) | 1.12 (0.99-2.33) | .057 | ||||||

| Liver metastasis | ||||||||

| 0 | ||||||||

| <=3, <=5 cm | ||||||||

| >3 or >5 cm | ||||||||

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CI, confidence interval; DP, double positivity; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; WT, wild-type.

S1: multivariate model including only the variables with a P value <.1 in the univariate analysis.

S2: multivariate model adjusted via automated stepwise selection of variables (see text for details).

Median OS (95% CI) was 39.8 months (27.0-not estimable) for DP patients and 18.9 months (11.0-36.6) for non-DP patients in the PULSE trial (P=.029). Median OS (95% CI) was 26.1 months (12.3-38.6) for DP patients and 31.0 months (26.2-37.5) for non-DP patients in the POSIBA trial (P=.027, Figure 2). DP was associated with prolonged OS in the PULSE trial (adjusted HR: 0.23: 95% CI: 0.11-0.52; P=.0004) and with shorter OS in the POSIBA trial (adjusted HR: 1.67; 95% CI: 0.96-2.90; P=.07) (Table 4). Sensitivity analysis did not change results substantially (Table 5).

Table 4.

Overall Survival; Cox Regression Analysis

| POSIBA |

PULSE |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| DP | 1.73 (1.06-2.85) | .029 | 1.67 (0.96-2.90) | .070 | 0.54 (0.29-0.99) | .048 | 0.23 (0.11-0.52) | .0004 |

| ECOG-PS >0 | 2.95 (2.03-4.29) | <.0001 | 2.48 (1.63-3.77) | <.0001 | 2.20 (1.18-4.08) | .013 | 2.93 (1.30-6.62) | .0097 |

| Age >65 years | 1.24 (0.85-1.79) | .26 | 1.00 (0.65-1.53) | .99 | 1.37 (0.74-2.53) | .32 | 1.48 (0.64-3.47) | .36 |

| BRAF mutated | 3.38 (2.00-5.72) | <.0001 | 2.32 (1.23-4.36) | .0092 | 4.23 (1.17-10.48) | .0018 | 10.3 (1.08-58.3) | .0086 |

| Surgery of primary tumor | 1.60 (1.10-2.32) | .013 | 1.36 (0.90-2.07) | .15 | 0.35 (0.19-0.66) | .0010 | 0.20 (0.08-0.48) | .0003 |

| Left-sided primary tumor | 1.06 (0.73-1.53) | .78 | 0.82 (0.51-1.31) | .40 | 0.60 (0.28-1.31) | .20 | 0.47 (0.15-1.48) | .20 |

| CEA (logarithmic term) | 0.42 (0.28-0.62) | <.0001 | 0.47 (0.30-0.74) | .0012 | 1.09 (0.94-1.25) | .25 | 0.91 (0.75-1.10) | .32 |

| LDH (logarithmic term) | 0.99 (0.91-1.08) | .80 | 1.00 (0.89-1.12) | .97 | 1.30 (0.85-2.01) | .23 | 1.40 (0.79-2.43) | .25 |

| Liver metastasis | 0.95 (0.72-1.26) | .73 | 0.92 (0.66-1.27) | .61 | ||||

| 0 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| <=3, <=5 cm | 0.68 (0.39-1.21) | .19 | 1.08 (0.57-2.06) | .81 | 1.72 (0.54-5.46) | .35 | 2.49 (0.56-11.09) | .23 |

| >3 or >5 cm | 0.70 (0.45-1.10) | .12 | 0.95 (0.51-1.79) | .88 | 1.73 (0.75-3.95) | .20 | 1.64 (0.49-5.50) | .42 |

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CI, confidence interval; DP, double positivity; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; WT, wild-type.

Table 5.

Sensitivity Analysis for Overall Survival; Cox Regression Analysis

| POSIBA |

PULSE |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate S1 |

Multivariate S2 |

Multivariate S1 |

Multivariate S2 |

|||||

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| DP | 1.60 (0.96-2.67) | .072 | 1.72 (1.01-2.94) | .048 | 0.36 (0.19-0.69) | .0019 | 0.36 (0.19-0.69) | .0019 |

| ECOG-PS >0 | 2.31 (1.56-3.43) | <.0001 | 2.49 (1.65-3.76) | <.0001 | 2.16 (1.10-4.25) | .026 | 2.16 (1.10-4.25) | .026 |

| Age >65 years | ||||||||

| BRAF mutated | 2.40 (1.38-4.17) | .0019 | 2.57 (1.47-4.49) | .0010 | 3.52 (1.32-9.35) | .012 | 3.52 (1.32-9.35) | .012 |

| Surgery of primary tumor | 1.29 (0.88-1.90) | .19 | 0.33 (0.17-0.64) | .0013 | 0.33 (0.17-0.64) | .0013 | ||

| Left-sided primary tumor | ||||||||

| CEA (logarithmic term) | 0.50 (0.33-0.75) | .0008 | 0.50 (0.32-0.76) | .0014 | ||||

| LDH (logarithmic term) | ||||||||

| Liver metastasis | ||||||||

| 0 | ||||||||

| <=3, <=5 cm | ||||||||

| >3 or >5 cm | ||||||||

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CI, confidence interval; DP, double positivity; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; WT, wild-type.

S1: multivariate model including only the variables with a P value <.1 in the univariate analysis.

S2: multivariate model adjusted via automated stepwise selection of variables (see text for details).

Response rates were similar according to DP in both the PULSE and POSIBA studies (Table 6). There were no major differences in terms of secondary resection of metastases and second-line therapies between PULSE and POSIBA trials and between DP and non-DP groups (data not shown).

Table 6.

Response Rates by Trial and Double Positivity

| POSIBA |

PULSE |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-DP | DP | P Value⁎ | Non-DP | DP | P Value⁎ | |

| Complete response | 13 (8.2) | 4 (17.4) | .17 | 3 (10.0) | 2 (5.4) | .28 |

| Partial response | 101 (63.9) | 11 (47.8) | 19 (63.3) | 25 (67.6) | ||

| Stable disease | 27 (17.1) | 4 (17.4) | 1 (3.3) | 7 (18.9) | ||

| Progressive disease | 9 (5.7) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (3.3) | 3 (8.1) | ||

| Not evaluable | 8 (5.1) | 1 (4.4) | 6 (20.0) | 0 | ||

DP, double positivity.

Fisher’s exact test.

Safety

The most common AEs (any grade) in the PULSE trial were skin toxicity (91%), fatigue (70%), and mucositis (67%) (Table 7). The most common AE (any grade) in the POSIBA trial were skin toxicity (76%), fatigue (55%), and diarrhea (50%) (Suppl. Table 1). Three patients died within 30 days of receiving protocol therapy: one patient in PULSE and two patients in POSIBA trial.

Table 7.

Summary of Adverse Events in the PULSE Trial

| Any Grade |

Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients (%) | |||

| Any event | 78 (100) | 55 (70.5) | 10 (12.8) |

| Skin toxicity | 71 (91.0) | 24 (30.8) | 0 (0) |

| Fatigue | 55 (70.5) | 12 (15.4) | 1 (1.3) |

| Mucositis | 52 (66.7) | 6 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diarrhea | 48 (61.5) | 11 (14.1) | 1 (1.3) |

| Neutropenia | 44 (56.4) | 26 (33.3) | 2 (2.6) |

| Nauseas/vomiting | 30 (38.5) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 28 (35.9) | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 23 (29.5) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.6) |

| Neurologic toxicity | 16 (20.5) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Anaemia | 10 (12.8) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Paronychia | 8 (10.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Infusion-related reaction | 7 (9.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hypokalemia | 6 (7.7) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 3 (3.9) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.6) |

Discussion

We present data from two prospective, multicenter, translational, first-line trials in WT RAS mCRC patients. Our findings suggests that there is a survival benefit in the subset of DP patients treated with upfront FOLFOX plus panitumumab schedule and in non-DP patients treated upfront with FOLFOX/FOLFIRI plus cetuximab therapy. This benefit was observed after adjustment for baseline characteristics, secondary surgery of metastases, and second-line therapies.

Recent evidence shows that RAS WT patients with right-side primary tumors have shorter overall survival than those with left-sided tumors and that left-sided tumors obtain greater benefit when treated with chemotherapy and anti-EGFR combinations [22], although the biological reasons remain obscure. Consensus molecular subtype clasification (CMS) associates the stromal-enriched mesenchymal phenotype (CMS4) [23] with poor prognosis [24], [25] and cetuximab resistance [26]. Despite data from Medema group suggesting that BRAF mutant CRC patients are enriched with CDX2−/ZEB1+ CMS4 phenotype [27], BRAF mutant mCRC patients are equally distributed between right- and left-sided, and 75% of right-sided patients treated with anti-EGFR present double WT genotype. Therefore, other CMS4 markers besides CDX2−/ZEB1+ and DP, such as CCL2 or CXCL12 (for both BRAF mutant and double WT genotypes), might be probably overrepresented in right-sided tumors. We could not rule out that, for currently unknown reasons, CMS4 phenotype might be induced by chemotherapy and anti-EGFR treatment [28] differently in both sides, influencing acquired resistance [29], [30].

We designed the PULSE trial based on retrospective data [21] hypothesizing that DP patients treated with panitumumab-based therapy could have also poor prognosis. It’s important to emphasize that the PULSE was designed in a different population (naïve) and with a different anti-EGFR exposure (panitumumab instead of cetuximab). Despite confirming our previous findings with FOLFIRI/FOLFOX plus cetuximab in the POSIBA trial, we could not confirm these results in the PULSE trial with panitumumab. In addition to inhibition of EGFR mitogenic pathways (MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and JAK/STAT), monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab and panitumumab) possess the potential advantage of recruiting immune effector mechanisms such as antibody-dependent cell mediated-cytotoxicity (ADCC) [31], although cetuximab was shown to be more effective in this mechanism than panitumumab. Although potentially cetuximab can activate ADCC also through NK cells, these cells are almost absent in colorectal cancer, and cetuximab in M2 macrophages activates anti-inflammatory IL-10 cytokines and proangiogenic factors (IL-8 and VEGF) [24]. Taking into account that: a) DP status could increase over time after chemotherapy treatment [29] and b) IGF-1R and STAT3 activation induces T-cell tolerance through TGF-B, IL-10 and VEGF [32] and also increases chemokines and cytokines such as IL-6 and CCL2 towards macrophage M2 polarization [33], we speculate that cetuximab but not panitumumab could be influenced by DP-CMS4 acquired resistance through immune evasion.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, PFS was evaluated differentialy (every 2 months in the PULSE trial and every 3 months in the POSIBA trial). Secondly, the percentage of DP positivity widely differs in both studies (33% in PULSE and 13% in POSIBA). Thirdly, the explanation on a potential biological reason for the contradictory results of our biomarker should be clarified.

We believe that our findings would have potential clinical importance and definitively justify a prospectively enriched-biomarker design in RAS WT patients with an experimental arm based on the biomarker (DP-treated with panitumumab and non–DP-treated with cetuximab) and a control arm (without this information) treated at investigator criteria (cetuximab or panitumumab).

Conclusions

Our study suggest that panitumumab is more benefitial for those RAS WT mCRC patients with a DP phenotype and cetuximab for those without it in terms of overall survival after adjusting for all clinical and biological confounder variables in the multivariate analysis.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Summary of Adverse Events in the POSIBA Study

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authorship

J. M. and X. G.-A. concieved and designed the study; J. M., X. G.-A., and V. A. analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript; X. G.-A. performed the statistical analysis. All authors adquired the study data, revised the manuscript, and approved its final version.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Study collaborators:

PULSE trial: Carlos Pericay, Jorge Aparicio, Alberto Carmona-Bayonas, Enrique Casado, Maria Jose Safont, Ruth Vera, Monica Jorge, Pedro Salinas, Antonio Arrivi, Javier Rodriguez

POSIBA trial: Uriel Bohn, Veronica Calderero, Ana Isabel Ferrer, Joaquin Perez de Oleguer, Rosa Dueñas, Ana Leon, Pilar Vicente, Angeles Rodriguez-Jaraiz, Isabel Antón, Olvia Serra, Isabel Busquier, Adelaida Lacasta, Carlos Garcia-Girón

The authors would like to thank Juan Martin (TFS Develop) for providing editing support (funded by Amgen S.A. [Spain]).

Funding / Role of the Funding Source

Amgen supported the PULSE trial and Merck supported the POSIBA trial. Neither Amgen nor Merck had any role in the present analysis design, analysis and interpretation of data, writing the report, and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Contributor Information

Vicente Alonso, Email: alonord@gmail.com.

Pilar Escudero, Email: pescudero@salud.aragon.es.

Carlos Fernández-Martos, Email: cfmartos@fivo.org.

Antonia Salud, Email: asaluds@hotmail.com.

Miguel Méndez, Email: mendezmiguel34@gmail.com.

Javier Gallego, Email: j.gallegoplazas@gmail.com.

Jose-R. Rodriguez, Email: joraromo@gmail.com.

Marta Martín-Richard, Email: mmartinri@santpau.es.

Julen Fernández-Plana, Email: julenfernandez@mutuaterrassa.es.

Hermini Manzano, Email: hermini.manzano@ssib.es.

José-Carlos Méndez, Email: jcmendez.m@gmail.com.

Monserrat Zanui, Email: mzanui@csdm.cat.

Esther Falcó, Email: efalco@hsll.es.

Mireia Gil-Raga, Email: mir-gil@hotmail.com.

Federico Rojo, Email: frojo@fjd.es.

Miriam Cuatrecasas, Email: mcuatrec@clinic.ub.es.

Jaime Feliu, Email: jfeliu-hulp@saludmadrid.org.

Xabier García-Albéniz, Email: xabieradrian@hotmail.com.

Joan Maurel, Email: jmaurel@clinic.cat.

References

- 1.Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham D, Jassem J. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1023–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Cutsem E, Lenz HJ, Köhne CH, Heinemann V, Tejpar S, Melezínek I, Beier F, Stroh C, Rougier P, van Krieken JH. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:692–700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venook A.P., Niedzwiecki D., Lenz H.J., Innocenti F., Fruth B., Meyerhardt J.A., Schrag D., Greene C., O'Neil B.H., Atkins J.N. Effect of first-line chemotherapy combined with cetuximab or bevacizumab on overall survival in patients with KRAS wild-type advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:2392–2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baserga R. Customizing the targeting of IGF-1 receptor. Future Oncol. 2009;5:43–50. doi: 10.2217/14796694.5.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollak M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:915–928. doi: 10.1038/nrc2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girnita L, Girnita A, Brodin B, Xie Y, Nilsson G, Dricu A, Lundeberg J, Wejde J, Bartolazzi A, Wiman KG. Increased expression of insulin-like growth factor I receptor in malignant cells expressing aberrant p53: functional impact. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5278–5283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner H, LeRoith D. The role of the insulin-like growth factor system in human cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1996;68:183–223. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60354-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dallas NA, Xia L, Fan F, Gray MJ, Gaur P, van Buren G, II, Samuel S, Kim MP, Lim SJ, Ellis LM. Chemoresistant colorectal cancer cells, the cancer stem cell phenotype, and increased sensitivity to insulin-like growth factor-I receptor inhibition. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1951–1957. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin L, Liu A, Peng Z, Lin HJ, Li PK, Li C, Lin J. STAT3 is necessary for proliferation and survival in colon cancer-initiating cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7226–7237. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon AR, Vikis HG, Stewart S, Fanburg BL, Cochran BH, Guan KL. Regulation of STAT3 by direct binding to the Rac1 GTPase. Science. 2000;290:144–147. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rokavec M, Öner MG, Li H, Jackstadt R, Jiang L, Lodygin D, Kaller M., Horst D, Ziegler PK, Schwitalla S. IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a feedback loop promotes EMT-mediated colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1853–1867. doi: 10.1172/JCI73531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lesina M, Kurkowski MU, Ludes K, Rose-John S, Treiber M, Klöppel G, Yoshimura A, Reindl W, Sipos B, Akira S. Stat3/Socs3 activation by IL-6 transsignaling promotes progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and development of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:456–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda A, Wang SC, Morris JP, IV, Folias AE, Liou A, Kim GE, Akira S, Boucher KM, Firpo MA, Mulvihill SJ. Stat3 and MMP7 contribute to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma initiation and progression. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:441–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao C, Su L, Shan J, Zhu C, Liu L, Liu C, Xu Y, Yang Z, Bian X, Shao J. IGF/STAT3/NANOG/Slug signaling axis simultaneously controls epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stemness maintenance in colorectal cancer. Stem Cells. 2016;34:820–831. doi: 10.1002/stem.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyamoto S, Yano K, Sugimoto S, Ishii G, Hasebe T, Endoh Y, Kodama K, Goya M, Chiba T, Ochiai A. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 facilitates insulin-like growth factor bioavailability through its proteinase activity on insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3. Cancer Res. 2004;64:665–671. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura M, Miyamoto S, Maeda H, Ishii G, Hasebe T, Chiba T, Asaka M, Ochiai A. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 degrades all insulin-like growth factor binding proteins and facilitates insulin-like growth factor bioavailability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:1011–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemers E, Duval C, McCaig C, Handley M, Dockray GJ, Varro A. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 is a target of matrix metalloproteinase-7: implications for epithelial-mesenchymal signaling. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7363–7369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyamoto S, Nakamura M, Yano K, Ishii G, Hasebe T, Endoh Y, Sangai T, Maeda H, Shi-Chuang Z, Chiba T. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 triggers the matricrine action of insulin-like growth factor-II via proteinase activity on insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 in the extracellular matrix. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:685–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams AC, Smartt H, H-Zadeh AM, Macfarlane M, Paraskeva C, Collard TJ. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) potentiates TRAIL-induced apoptosis of human colorectal carcinoma cells through inhibition of NF-kappaB. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:137–145. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adachi Y, Li R, Yamamoto H, Min Y, Piao W, Wang Y, Imsumran A, Li H, Arimura Y, Lee CT. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor blockade reduces the invasiveness of gastrointestinal cancers via blocking production of matrilysin. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1305–1313. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hörndler C, Gallego R, García-Albeniz X, Alonso-Espinaco V, Alonso V, Escudero P, Jimeno M, Ortego J, Codony-Servat J, Fernández-Martos C. Co-expression of matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7) and phosphorylated insulin growth factor receptor I (pIGF-1R) correlates with poor prognosis in patients with wild-type KRAS treated with cetuximab or panitumumab: a GEMCAD study. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:177–183. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.2.13839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold D, Lueza B, Douillard JY, Peeters M, Lenz HJ, Venook A, Heinemann V, Van Cutsem E, Pignon JP, Tabernero J. Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1713–1729. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becht E, de Reyniès A, Giraldo NA, Pilati C, Buttard B, Lacroix L, Selves J, Sautès-Fridman C, Laurent-Puig P, Fridman WH. Immune and stromal classification of colorectal cancer is associated with molecular subtypes and relevant for precision immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:4057–4066. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reyniès A, Schlicker A, Soneson C, Marisa L, Roepman P, Nyamundanda G, Angelino P. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2015;21:1350–1356. doi: 10.1038/nm.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Sousa E Melo F, Wang X, Jansen M, Fessler E, Trinh A, de Rooij LP, de Jong JH, de Boer OJ, van Leersum R, Bijlsma MF. Poor-prognosis colon cancer is defined by a molecularly distinct subtype and develops from serrated precursor lesions. Nat Med. 2013;19:614–618. doi: 10.1038/nm.3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trinh A, Trumpi K, De Sousa E Melo F, Wang X, de Jong JH, Fessler E, Kuppen PJ, Reimers MS, Swets M, Koopman M. Practical and robust identification of molecular subtypes in colorectal cancer by immunohistochemistry. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:387–398. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fessler E, Drost J, van Hooff SR, Linnekamp JF, Wang X, Jansen M, De Sousa E Melo F, Prasetyanti PR, IJspeert JE, Franitza M. TGFβ signaling directs serrated adenomas to the mesenchymal colorectal cancer subtype. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:745–760. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trumpi K, Ubink I, Trinh A, Djafarihamedani M, Jongen JM, Govaert KM, Elias SG, van Hooff SR, Medema JP, Lacle MM. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy affects molecular classification of colorectal tumors. Oncogenesis. 2017;6 doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2017.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallego R, Codony-Servat J, García-Albéniz X, Carcereny E, Longarón R, Oliveras A, Tosca M, Augé JM, Gascón P, Maurel J. Serum IGF-I, IGFBP-3, and matrix metalloproteinase-7 levels and acquired chemo-resistance in advanced colorectal cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:311–317. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadal C, Maurel J, Gallego R, Castells A, Longarón R, Marmol M, Sanz S, Molina R, Martin-Richard M, Gascón P. FAS/FAS ligand ratio: a marker of oxaliplatin-based intrinsic and acquired resistance in advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4770–4774. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider-Merck T, Lammerts van Bueren JJ, Berger S, Rossen K, van Berkel PH, Derer S, Beyer T, Lohse S, Bleeker WK, Peipp M. Human IgG2 antibodies against epidermal growth factor receptor effectively trigger antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity but, in contrast to IgG1, only by cells of myeloid lineage. J Immunol. 2010;184:512–520. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trivedi S, Concha-Benavente F, Srivastava RM, Jie HB, Gibson SP, Schmitt NC, Ferris RL. Immune biomarkers of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:40–47. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez-Lopez E, Flashner-Abramson E, Shalapour S, Zhong Z, Taniguchi K, Levitzki A, Karin M. Targeting colorectal cancer via its microenvironment by inhibiting IGF-1 receptor-insulin receptor substrate and STAT3 signaling. Oncogene. 2016;35:2634–2644. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of Adverse Events in the POSIBA Study