Abstract

The adult human skeleton is a multifunctional organ undergoing constant remodeling through the opposing activities of the bone-resorbing osteoclast and the bone-forming osteoblast. The exquisite balance between bone resorption and bone formation is responsible for bone homeostasis in healthy adults. However, evidence has emerged that such a balance is likely disrupted in diabetes where systemic glucose metabolism is dysregulated, resulting in increased bone frailty and osteoporotic fractures. These findings therefore underscore the significance of understanding the role and regulation of glucose metabolism in bone under both normal and pathological conditions. Recent studies have shed new light on the metabolic plasticity and the critical functions of glucose metabolism during osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation. Moreover, these studies have begun to identify intersections between glucose metabolism and the growth factors and transcription factors previously known to regulate osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Here we summarize the current knowledge in the nascent field, and suggest that a fundamental understanding of glucose metabolic pathways in the critical bone cell types may open new avenues for developing novel bone therapeutics.

Keywords: Glycolysis, Glucose, Metabolism, Oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), Mitochondria, Osteoblast, Osteoclast, Bone, Osteoporosis, Diabetes

1. Introduction

Bone fractures associated with osteopenia and osteoporosis pose a major health threat especially among the aging population. Despite the recent progress in therapies such as denosumab and abaloparatide, additional safe and effective strategies are necessary to improve bone mass and quality to treat osteoporosis. Because osteoblasts and osteoclasts are the chief cell types regulating bone homeostasis, elucidating the mechanisms that regulate their differentiation and activity is critical not only for understanding bone physiology but also for designing effective bone therapeutics. Extensive studies in the area during the past several decades have mostly focused on the regulation of cell-type-specific marker genes by endocrine or paracrine signals or transcriptional factors [1–4]. A critical aspect of cell differentiation is the acquisition of specific cellular functions, these including bone matrix deposition by the osteoblast or protease and acid secretion by the osteoclast. However, the bioenergetics in support of the cell-specific physiological activity is just beginning to be explored [5]. This review summarizes the current understanding about the role of glucose metabolism in osteoblasts and osteoclasts.

2. Glucose metabolism in mammalian cells

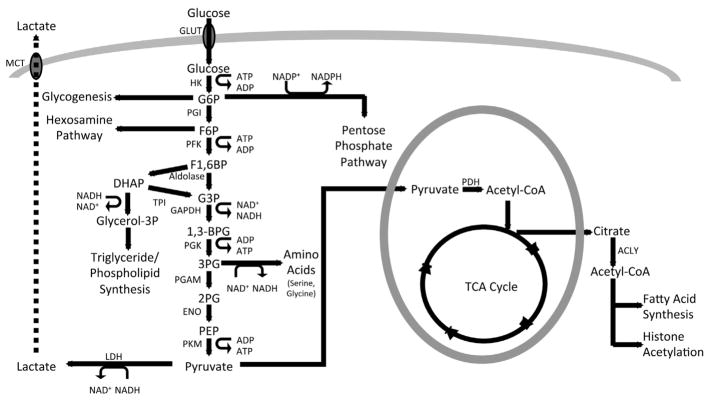

Glucose is a major energy source for most mammalian cell types. Upon transport into the cell via the Glut family of transporters down a concentration gradient independent of ATP, glucose is metabolized in the cytoplasm through glycolysis to produce two pyruvate molecules, 2 ATP, and two reducing equivalents in the form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) [5–7] (Fig. 1). The first stage of glycolysis culminates in the generation of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (F1,6 BP), which is then cleaved to form two interconvertible three carbon molecules glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P) and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP). During the final stage of glycolysis, G3P is eventually converted to pyruvate, producing ATP in the process. In addition to the core glycolysis pathway, glycolytic intermediates can enter other metabolic pathways in the cell. For example, G6P can be converted to glycogen for storage or be metabolized via the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). The PPP is important for generating not only ribose 5-phosphate, the backbone of nucleic acids, but also the reducing equivalent nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) essential for reductive biosynthetic reactions and for redox homeostasis via glutathione (GSH) and thioredoxin (TRX) [8]. In addition, Fructose-6-P (F6P) derived from G6P can enter the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP) which produces uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDPGlcNAc) for protein glycosylation. Finally, 3-Phosphoglycerate (3PG) can be metabolized via the serine biosynthetic pathway to produce serine and subsequently glycine, a process integral to one-carbon metabolism required for methylation of DNA and histones, NADPH production as well as GSH biosynthesis [8–10]. Overall, glycolysis produces numerous intermediate metabolites critical for various biosynthetic pathways.

Fig. 1.

Glucose metabolism in mammalian cells. Protein abbreviations: GLUT – Glucose Transporter; HK – Hexokinase; PGI – Phosphoglucose Isomerase. PFK – Phosphofructokinase; TPI –Triose Phosphate Isomerase; GAPDH – Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate Dehydrogenase; PGK – Phosphoglycerate Kinase; PGAM –Phosphoglycerate Mutase; ENO – Enolase; PKM – Pyruvate Kinase, Muscle; LDH – Lactate Dehydrogenase; PDH – Pyruvate Dehydrogenase; ACLY: ATP citrate lyase; MCT – Monocarboxylate Transporter. Metabolite abbreviations: G6P – Glucose 6-phosphate; F6P – Fructose 6-phosphate; F1,6BP – Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; DHAP – Dihydroxyacetone Phosphate; G3P – Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; 1,3BPG – 1,3-Bisphosphoglycerate; 3PG – 3-Phosphoglycerate; 2PG – 2-Phosphoglycerate; PEP – Phosphoenolpyruvate.

The glycolytic end product pyruvate can be either converted to lactate or further oxidized in the TCA cycle. Pyruvate conversion into lactate is catalyzed by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) independent of oxygen and regenerates the oxidized NAD (NAD+) necessary for further glycolysis. Alternatively, pyruvate can be decarboxylated to form acetyl-CoA by the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). Pyruvate oxidation in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle produces the most ATP per glucose molecule through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Importantly, TCA intermediates are often extracted from the cycle through a process known as cataplerosis to support lipid and amino acid biosynthesis, redox regulation and epigenetic regulation of gene expression [11–13]. Thus, glucose is not only an important energy source but also a critical provider of intermediate metabolites necessary for supporting cellular homeostasis and function.

3. Glucose metabolism in osteoblasts

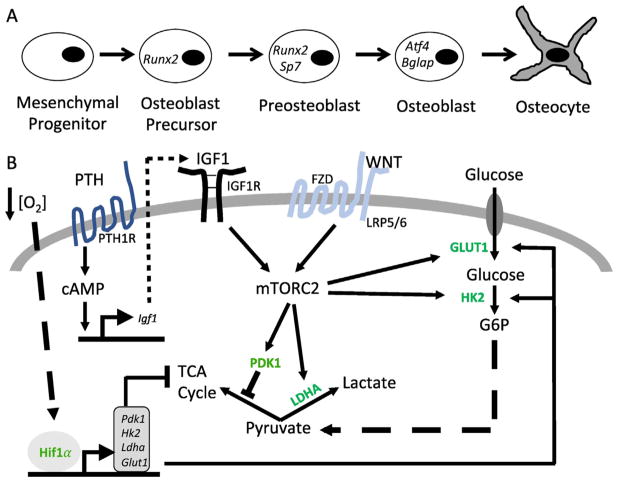

The bone-forming osteoblasts differentiate through a series of stages characterized by the expression of distinct transcription factors and marker genes [2]. Originated from the mesenchymal progenitors, early osteoblast precursors express the transcription factor Runx2 whereas the more specified preosteoblasts express osterix (Osx or Sp7) (Fig. 2A). Upon further differentiation, the mature osteoblasts activate Atf4 and upregulate the expression of collagen I as well as other matrix proteins including integrin binding sialoprotein (Ibsp) and osteocalcin (Bglap). Whereas most osteoblasts are believed to undergo apoptosis, some become entombed in the bone matrix and further differentiate to osteocytes. Although much has been learned about the transcriptional regulation of osteoblast differentiation, relatively little is understood how cellular metabolism is modulated to accommodate the active bio-synthetic activity of mature osteoblasts.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of glucose metabolism in osteoblast lineage. (A) A schematic of osteoblast differentiation. Representative marker genes are denoted at specific stages. (B) Signal pathways regulating glucose metabolism during osteoblast differentiation. PTH – Parathyroid Hormone. PTH1R – Parathyroid Hormone 1 Receptor. IGF1 – Insulin Like Growth Factor 1. IGF1R –Insulin Like Growth Factor 1 Receptor. FZD – Frizzled. LRP5/6 – Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 5 or 6. cAMP: Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate. Hif1a - Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1a. GLUT1 – Glucose Transporter 1; HK2 – Hexokinase 2; LDHA – Lactate Dehydrogenase A; PDK1 – Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 1. Bent arrows denote gene transcription. Arrows and blocked arrows indicate stimulation and inhibition, respectively.

Glucose has been long recognized as an important nutrient for the osteoblast lineages, as indicated by the early studies of either bone explants or isolated osteoblastic cells [14–16]. Consistent with their glucose consumption, the osteoblast-lineage cells have been shown to express several Glut family transporters. For instance, the rat bone-derived osteoblastic PyMS cells were reported to express Glut1, Glut3 but not Glut4 [17]. A more recent study, however, showed that Glut4 was also detectable in primary cultures of murine calvarial preosteoblasts and was up-regulated upon further differentiation towards osteoblasts in vitro, whereas Glut1 and Glut3 expression stayed relatively constant [18]. Furthermore, Glut4 appeared to be responsible for the insulin-induced glucose uptake in osteoblasts even though its deletion did not impair bone formation in the mouse [18]. On the other hand, Glut1, expressed at the highest level among the Gluts in the osteoblast lineage, has been shown to engage in a feed-forward mechanism with Runx2 to determine not only the onset of osteoblast differentiation during embryogenesis but also the extent of bone formation throughout life [19]. Future genetic studies are necessary to determine the role of Glut3 and any potential functional overlap with Glut1 in the osteoblast lineage.

Osteoblasts appear to metabolize glucose mostly into lactate even in the presence of sufficient oxygen, a process known as aerobic glycolysis [20]. The phenomenon was documented initially in bone explants and later in isolated osteoblasts [16,21–23]. More recent studies have confirmed an increase in aerobic glycolysis in primary calvarial preosteoblasts when they further differentiate in response to ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate [24,25]. Aerobic glycolysis occurs despite the fact that mature osteoblasts possess numerous mitochondria and exhibit active OXPHOS [24,26,27]. Thus, other nutrients besides glucose, such as fatty acids and glutamine as implicated by recent studies, may be fueling the mitochondrial respiration in mature osteoblasts [28,29].

Accumulating evidence has indicated that glycolysis in osteoblast-lineage cells is directly stimulated by various bone anabolic signals. Long before parathyroid hormone (PTH) signaling was harnessed clinically to promote bone formation in osteoporotic patients, it was historically shown to stimulate glucose consumption and lactate production in bone explants [16,30,31]. More recently, a mechanistic study has demonstrated that PTH signaling enhances aerobic glycolysis indirectly through the transcriptional induction of Igf1 that in turn signals through mTORC2 to elevate various glycolytic enzymes [32] (Fig. 2B). Importantly, diminution of aerobic glycolysis with dichloacetate (DCA) that increases pyruvate entry to the TCA cycle notably suppressed the bone anabolic effect of PTH, thus demonstrating a functional link between glycolysis and bone formation [32]. In further support of the connection, stimulating glycolysis through overexpression of Hif1a known to induce the transcription of multiple glycolytic genes, increased bone formation in vivo, and the effect was effectively reversed by DCA [33] (Fig. 2B). Besides PTH, the bone anabolic Wnt proteins also promote aerobic glycolysis in osteoblast lineage cells [34]. In particular, Wnt3a-Lrp5 signaling acutely increased the levels of Glut1, Hk2, Ldha and Pdk1 downstream of mTORC2 and Akt activation while inducing osteoblast differentiation from the bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cell line ST2 [35] (Fig. 2B). Whereas upregulation of Glut1 and Hk2 is expected to stimulate the overall rate of glycolysis, increased Ldha and Pdk1 would favor lactate production from pyruvate, thus altering the metabolic profile towards that of an osteoblast. In support of the role of mTORC2 in Wnt-induced bone formation, deletion of Rictor that is uniquely required for mTORC2 signaling not only reduced physiological bone formation but also blunted the anabolic effect of an anti-sclerostin therapy designed to boost Wnt interaction with the receptors [36,37]. Finally, Hedgehog (Hh) signaling, a critical inducer of the early steps of osteoblast differentiation, has been reported to stimulate aerobic glycolysis in both muscle and brown adipose tissue through a non-canonical mechanism [38,39]. Although a similar metabolic regulation by Hh has not been described during osteoblast differentiation, Hh signaling has been shown to induce Igf2 expression via Gli2, resulting in mTORC2 activation in the osteogenic progenitors [40]. Thus, it will be of interest to examine the potential relationship between Hh signaling and glycolysis in bone formation.

Currently, it remains unclear why osteoblasts have a propensity for aerobic glycolysis. Compared to metabolism through the TCA cycle and OXPHOS, aerobic glycolysis is a far less efficient means of producing ATP from glucose. However, aerobic glycolysis may be necessary in order for osteoblasts to generate sufficient intermediate metabolites to sustain active biosynthesis. In addition, aerobic glycolysis may be beneficial for offsetting reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated from OXPHOS as ROS was shown to favor adipogenesis from mesenchymal progenitors [41,42]. Another interesting possibility is that glycolytic changes could directly affect the levels of enzymatic cofactors (e.g., alpha-ketoglutarate) or substrates (e.g., acetyl-CoA) necessary for epigenetic modifications in differentiation [11,43]. For instance, increased aerobic glycolysis in response to Wnt signaling has been correlated with reduced nuclear levels of both citrate and acetyl-CoA, which could explain the large scale decrease in histone acetylation and suppression of adipogenic and chondrogenic transcription factors in mesenchymal progenitors [44]. However, further studies are warranted to elucidate the full mechanism whereby aerobic glycolysis promotes the osteoblast phenotype.

4. Glucose metabolism in osteoclasts

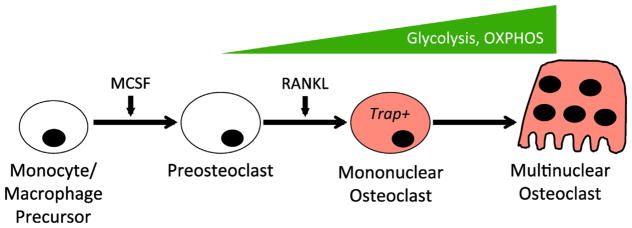

Osteoclasts are giant, multinucleated cells responsible for resorbing the bone matrix and maintaining mineral homeostasis. Osteoclasts form by differentiation and fusion of monocytic precursors of the macrophage lineage in response to macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) [1,4]. During RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation from murine bone marrow macrophages, both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) as well as lactate production were found to increase [45] (Fig. 3). The increase in OXPHOS is consistent with a substantial increase in the number, the size and the cristae abundance of mitochondria with osteoclast differentiation [46]. Interestingly, osteoclastogenesis appeared to be optimal with glucose at approximately 5 mM in the in vitro differentiation system, whereas high levels of glucose such as 20 mM were less effective even though cell proliferation was maximally stimulated. Furthermore, pyruvate was found to synergize with 5 mM glucose to stimulate osteoclast differentiation while reducing glucose consumption and lactate production, but inhibition of mitochondrial OXPHOS retarded osteoclastogenesis [45]. These results indicate that osteoclast differentiation is coupled with increased mitochondrial respiration that is at least partially fueled by the increased glycolysis. In support of the importance of glycolysis, depletion of Ldha or Ldhb was shown to reduce both glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration, resulting in suppression of osteoclastogenesis [47]. Remarkably however, limiting glycolysis by either omission of glucose in the culture media or knockdown of Hif1a did not impair osteoclastogenesis in vitro, indicating that alternative energy substrates were activated in those settings to support the differentiation process [48]. Indeed, glutamine was shown to be required for osteoclast differentiation, but whether it alone could compensate for the lack of glucose was not investigated [48]. Alternatively, pyruvate and fatty acids typically present in the culture medium may fuel OXPHOS to support osteoclast differentiation in the absence of glucose metabolism. Regardless of the exact fuel substrate, it is interesting that the compensatory mechanism was activated by glucose removal but apparently not by Ldh depletion. Future studies are necessary to decipher how fuel plasticity between glucose and the other substrates is regulated during osteoclastogenesis.

Fig. 3.

Metabolic regulation during osteoclast differentiation. Both glycolysis and OXPHOS increase during osteoclastogenesis. MCSF: macrophage colony stimulating factor; RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand.

The importance of mitochondrial respiration in osteoclasts has been demonstrated genetically. Disruption of mitochondrial complex I through deletion of Ndufs4 impaired osteoclast differentiation and function resulting in osteopetrosis in the mouse [49]. Deletion of the mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam) with cathepsin K-Cre in the mouse reduced intracellular ATP levels in osteoclasts and accelerated their apoptosis [50]. Molecularly, Rankl has been shown to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis via upregulation of the Pparg coactivator Ppargc1b during osteoclast differentiation [51]. Moreover, Asxl2, a regulator of histone methylation, appears to act upstream of Pparg1b to control mitochondrial biogenesis [52]. However, alternative NF-kb signaling via RelB and NIK is also required for mitochondrial biogenesis in response to Rankl, and this requirement is likely independent of Ppargc1b [53]. Therefore, further studies are necessary to elucidate the precise mechanism for Rankl to activate mitochondrial biogenesis integral to the osteoclastogenic program.

Glucose appears to be a major nutrient for mature osteoclasts. Earlier studies with chicken osteoclasts demonstrated that glucose, instead of fatty acids or ketone bodies, was the principle energy source for bone resorption, and that attachment to the bone surface greatly simulated glucose consumption by osteoclasts [54]. Glucose was further shown in chicken osteoclasts to stimulate both protein and mRNA levels of the vacuolar-type H+-ATPases (V-ATPase) essential for the resorptive activity of osteoclasts [55]. Similarly, limiting glucose metabolism by either omission of glucose in the culture media or knockdown of Hif1a reduced bone resorption by murine osteoclasts in vitro [48]. More recently, human osteoclasts were shown to rely on glycolysis for bone resorption, as reducing the rate of glycolysis with galactose significantly impaired collagen I degradation whereas suppression of the mitochondrial complex I with a non-cytotoxic dose of rotenone enhanced osteoclast activity [46]. Interestingly, immunostaining experiments revealed that some of the key glycolytic enzymes were localized to the actin ring of polarized osteoclasts attached to bone surface [46]. Therefore, in contrast to osteoclastogenesis that requires mitochondrial OXPHOS fueled by both glucose and potentially other substrates, the mature osteoclasts appear to rely heavily on active aerobic glycolysis to support bone resorption. Further studies however are necessary in this regard, as a study of osteoclasts in human osteophytes from osteoarthritis patients indicated active fatty acid oxidation and TCA metabolism in situ [56]. Whether these findings reflect the normal or a pathological state of metabolism in osteoclasts in vivo is not clear at present.

5. Clinical relevance

Systemic dysregulation of glucose metabolism due to the deficiency in either producing (type I) or responding to insulin (type II) is the hallmark of diabetes. Type I Diabetes in particular is associated with a variety of bone complications including reduced bone mineral density, increased fracture risk and poor fracture healing in both humans and rodent models [57,58]. Historically, the effects of diabetes on the skeleton have been primarily attributed to deleterious effects on osteoblasts and bone formation, but more recent data suggests that bone resorption is also affected [59–64]. The increased osteoclast numbers and bone resorption in several diabetic models may not be due to a direct effect of systemic glucose elevation as hyperglycemia has been shown to inhibit osteoclast differentiation and function in vitro [45,60,65–67]. Instead, increased osteoclastogenesis in diabetes could be secondary to hypoxia-induced acidosis in the bone marrow [68]. In addition, advanced glycation end products (AGEs) of lipids or proteins caused by hyperglycemia in diabetes may signal through the membrane RAGE to enhance bone resorption [69,70]. Mechanistically, AGEs dependent RAGE activation stimulates the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that may stimulate osteoclastogenesis through RANKL signaling [71,72]. Increased ROS may also impair bone formation by inhibiting osteoblast differentiation and promoting apoptosis [73–76]. Despite the progress, a clear and mechanistic understanding of the deleterious effects of diabetes on bone mass and quality awaits further studies. In particular, it is not clear whether and how glucose metabolism in osteoblasts or osteoclasts is altered in vivo under diabetic conditions, and more importantly whether such potential changes contribute to the pathology in bone.

The effects of insulin signaling on glucose metabolism in osteoblasts or osteoclasts also warrant further studies. Osteoblasts express the insulin receptor (IR) but whether or not insulin stimulates glucose uptake in osteoblasts has been a matter of debate [18,19]. Nonetheless, IR deletion in osteoblasts recapitulates the bone phenotypes present in diabetic mouse models, namely reduced osteoblast numbers, bone formation and bone mass [77]. IR signaling deficiency in osteoblasts is likely relevant to both types of diabetes as emerging evidence supports insulin resistance in osteoblasts in type II diabetes models [78,79]. In addition to low systemic insulin, type I diabetes is associated with decreased serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1) in both humans and rodent models [80,81]. As IGF1 signals through the IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) to directly stimulate osteoblast differentiation, matrix production and mineralization, IGF1 deficiency likely contributes to the bone formation deficit in diabetes [82–84]. Future studies are necessary to determine whether deficiency in IR or IGF1R signaling alters glucose metabolism in osteoblasts or osteoclasts to cause bone pathology associated with diabetes.

6. Conclusions

We have highlighted the major findings to date regarding the role and molecular regulation of glucose metabolism in osteoblasts and osteoclasts. A notable knowledge gap exists about the metabolic profile of osteocytes, the predominant cell type in bone. Although one might infer from the historical studies employing bone slices that osteocytes metabolize glucose mainly to lactate, a direct assessment of glucose metabolism in osteocytes is clearly necessary. Nonetheless, the existing literature supports a multifaceted role of glucose metabolism during physiological bone formation and bone resorption. The metabolic plasticity observed during osteoblast or osteoclast differentiation is particularly intriguing. Metabolic rewiring is likely to be integral to cell differentiation, but the mechanisms through which the metabolic changes contribute to the differentiated phenotype are undoubtedly complex and warrant further investigation. Genetic studies will be necessary to clarify the physiological roles of specific metabolic pathways in the various bone cell types. It is tempting to speculate that metabolic dysregulation at the cellular level might be involved in the bone pathology associated with diabetes. Although the mechanisms for diabetes-related bone fragility are undoubtedly complex, pharmaceutical targeting of cellular glucose metabolism may be a promising direction towards developing novel therapies to improve bone quality in diabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

Work in Long lab is supported by NIH grants AR060456 and AR055923.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Teitelbaum SL. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289:1504–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long F. Building strong bones: molecular regulation of the osteoblast lineage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;13:27–38. doi: 10.1038/nrm3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karsenty G, Kronenberg HM, Settembre C. Genetic control of bone formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:629–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee WC, Guntur AR, Long F, Rosen CJ. Energy metabolism of the osteoblast: implications for osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2017;38:255–266. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueckler M. Facilitative glucose transporters. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:713–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell GI, Burant CF, Takeda J, Gould GW. Structure and function of mammalian facilitative sugar transporters. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19161–19164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan J, Ye J, Kamphorst JJ, Shlomi T, Thompson CB, Rabinowitz JD. Quantitative flux analysis reveals folate-dependent NADPH production. Nature. 2014;510:298–302. doi: 10.1038/nature13236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis SR, Stacpoole PW, Williamson J, Kick LS, Quinlivan EP, Coats BS, Shane B, Bailey LB, Gregory JF., 3rd Tracer-derived total and folate-dependent homocysteine remethylation and synthesis rates in humans indicate that serine is the main one-carbon donor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E272–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00351.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddocks OD, Berkers CR, Mason SM, Zheng L, Blyth K, Gottlieb E, Vousden KH. Serine starvation induces stress and p53-dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature. 2013;493:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature11743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR, Thompson CB. ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science. 2009;324:1076–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1164097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439:811–816. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, Rao A. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohn DV, Forscher BK. Aerobic metabolism of glucose by bone. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:615–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peck WA, Birge SJ, Jr, Fedak SA. Bone cells: biochemical and biological studies after enzymatic isolation. Science. 1964;146:1476–1477. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3650.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borle AB, Nichols N, Nichols G., Jr Metabolic studies of bone in vitro. I. Normal bone. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:1206–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoidis E, Ghirlanda-Keller C, Schmid C. Stimulation of glucose transport in osteoblastic cells by parathyroid hormone and insulin-like growth factor I. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;348:33–42. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0634-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z, Frey JL, Wong GW, Faugere MC, Wolfgang MJ, Kim JK, Riddle RC, Clemens TL. Glucose transporter-4 facilitates insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in osteoblasts. Endocrinology. 2016 doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1583. (en20161583) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei J, Shimazu J, Makinistoglu MP, Maurizi A, Kajimura D, Zong H, Takarada T, Iezaki T, Pessin JE, Hinoi E, Karsenty G. Glucose uptake and Runx2 synergize to orchestrate osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2015;161:1576–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esen E, Long F. Aerobic glycolysis in osteoblasts. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2014;12:433–438. doi: 10.1007/s11914-014-0235-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neuman WF, Neuman MW, Brommage R. Aerobic glycolysis in bone: lactate production and gradients in calvaria. Am J Phys. 1978;234:C41–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1978.234.1.C41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felix R, Neuman WF, Fleisch H. Aerobic glycolysis in bone: lactic acid production by rat calvaria cells in culture. Am J Phys. 1978;234:C51–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1978.234.1.C51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohn DV, Forscher BK. Effect of parathyroid extract on the oxidation in vitro of glucose and the production of 14CO-2 by bone and kidney. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1962;65:20–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(62)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komarova SV, Ataullakhanov FI, Globus RK. Bioenergetics and mitochondrial transmembrane potential during differentiation of cultured osteoblasts. Am J Phys Cell Phys. 2000;279:C1220–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.4.C1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guntur AR, Le PT, Farber CR, Rosen CJ. Bioenergetics during calvarial osteoblast differentiation reflect strain differences in bone mass. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1589–1595. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Passi-Even L, Gazit D, Bab I. Ontogenesis of ultrastructural features during osteogenic differentiation in diffusion chamber cultures of marrow cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:589–595. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein BY, Gal I, Hartshtark Z, Segal D. Induction of osteoprogenitor cell differentiation in rat marrow stroma increases mitochondrial retention of rhodamine 123 in stromal cells. J Cell Biochem. 1993;53:190–197. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240530303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karner CM, Esen E, Okunade AL, Patterson BW, Long F. Increased glutamine catabolism mediates bone anabolism in response to WNT signaling. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:551–562. doi: 10.1172/JCI78470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frey JL, Li Z, Ellis JM, Zhang Q, Farber CR, Aja S, Wolfgang MJ, Clemens TL, Riddle RC. Wnt-Lrp5 signaling regulates fatty acid metabolism in the osteoblast. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:1979–1991. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01343-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichols FC, Neuman WF. Lactic acid production in mouse calvaria in vitro with and without parathyroid hormone stimulation: lack of acetazolamide effects. Bone. 1987;8(2):105–109. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(87)90078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodan GA, Rodan SB, Marks SC., Jr Parathyroid hormone stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity and lactic acid accumulation in calvaria of osteopetrotic (ia) rats. Endocrinology. 1978;102:1501–1505. doi: 10.1210/endo-102-5-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esen E, Lee SY, Wice BM, Long F. PTH promotes bone anabolism by stimulating aerobic glycolysis via IGF signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2015 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regan JN, Lim J, Shi Y, Joeng KS, Arbeit JM, Shohet RV, Long F. Up-regulation of glycolytic metabolism is required for HIF1alpha-driven bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8673–8678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324290111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karner CM, Long F. Wnt signaling and cellular metabolism in osteoblasts. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:1649–1657. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2425-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esen E, Chen J, Karner CM, Okunade AL, Patterson BW, Long F. WNT-LRP5 signaling induces Warburg effect through mTORC2 activation during osteoblast differentiation. Cell Metab. 2013;17:745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J, Holguin N, Shi Y, Silva MJ, Long F. mTORC2 signaling promotes skeletal growth and bone formation in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:369–378. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun W, Shi Y, Lee WC, Lee SY, Long F. Rictor is required for optimal bone accrual in response to anti-sclerostin therapy in the mouse. Bone. 2016;85:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long F, Chung UI, Ohba S, McMahon J, Kronenberg HM, McMahon AP. Ihh signaling is directly required for the osteoblast lineage in the endochondral skeleton. Development. 2004;131:1309–1318. doi: 10.1242/dev.01006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teperino R, Amann S, Bayer M, McGee SL, Loipetzberger A, Connor T, Jaeger C, Kammerer B, Winter L, Wiche G, Dalgaard K, Selvaraj M, Gaster M, Lee-Young RS, Febbraio MA, Knauf C, Cani PD, Aberger F, Penninger JM, Pospisilik JA, Esterbauer H. Hedgehog partial agonism drives Warburg-like metabolism in muscle and brown fat. Cell. 2012;151:414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi Y, Chen J, Karner CM, Long F. Hedgehog signaling activates a positive feedback mechanism involving insulin-like growth factors to induce osteoblast differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:4678–4683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502301112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang W, Zhang Y, Lu W, Liu K. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulate adipocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in hematopoietic stress induced by arabinosylcytosine. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tormos KV, Anso E, Hamanaka RB, Eisenbart J, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial complex III ROS regulate adipocyte differentiation. Cell Metab. 2011;14:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carey BW, Finley LW, Cross JR, Allis CD, Thompson CB. Intracellular alpha-ketoglutarate maintains the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2015;518:413–416. doi: 10.1038/nature13981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karner CM, Esen E, Chen J, Hsu FF, Turk J, Long F. Wnt protein signaling reduces nuclear acetyl-CoA levels to suppress gene expression during osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:13028–13039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.708578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JM, Jeong D, Kang HK, Jung SY, Kang SS, Min BM. Osteoclast precursors display dynamic metabolic shifts toward accelerated glucose metabolism at an early stage of RANKL-stimulated osteoclast differentiation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;20:935–946. doi: 10.1159/000110454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lemma S, Sboarina M, Porporato PE, Zini N, Sonveaux P, Di Pompo G, Baldini N, Avnet S. Energy metabolism in osteoclast formation and activity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;79:168–180. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahn H, Lee K, Kim JM, Kwon SH, Lee SH, Lee SY, Jeong D. Accelerated lactate dehydrogenase activity potentiates osteoclastogenesis via NFATc1 signaling. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Indo Y, Takeshita S, Ishii KA, Hoshii T, Aburatani H, Hirao A, Ikeda K. Metabolic regulation of osteoclast differentiation and function. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:2392–2399. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin Z, Wei W, Yang M, Du Y, Wan Y. Mitochondrial complex I activity suppresses inflammation and enhances bone resorption by shifting macrophage-osteoclast polarization. Cell Metab. 2014;20:483–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyazaki T, Iwasawa M, Nakashima T, Mori S, Shigemoto K, Nakamura H, Katagiri H, Takayanagi H, Tanaka S. Intracellular and extracellular ATP coordinately regulate the inverse correlation between osteoclast survival and bone resorption. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37808–37823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.385369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ishii KA, Fumoto T, Iwai K, Takeshita S, Ito M, Shimohata N, Aburatani H, Taketani S, Lelliott CJ, Vidal-Puig A, Ikeda K. Coordination of PGC-1beta and iron uptake in mitochondrial biogenesis and osteoclast activation. Nat Med. 2009;15:259–266. doi: 10.1038/nm.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Izawa T, Rohatgi N, Fukunaga T, Wang QT, Silva MJ, Gardner MJ, McDaniel ML, Abumrad NA, Semenkovich CF, Teitelbaum SL, Zou W. ASXL2 regulates glucose, lipid, and skeletal homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1625–1637. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeng R, Faccio R, Novack DV. Alternative NF-kappaB regulates RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation and mitochondrial biogenesis via independent mechanisms. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:2287–2299. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams JP, Blair HC, McDonald JM, McKenna MA, Jordan SE, Williford J, Hardy RW. Regulation of osteoclastic bone resorption by glucose. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:646–651. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larsen KI, Falany ML, Ponomareva LV, Wang W, Williams JP. Glucose-dependent regulation of osteoclast H(+)-ATPase expression: potential role of p38 MAP-kinase. J Cell Biochem. 2002;87:75–84. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dodds RA, Gowen M, Bradbeer JN. Microcytophotometric analysis of human osteoclast metabolism: lack of activity in certain oxidative pathways indicates inability to sustain biosynthesis during resorption. J Histochem Cytochem. 1994;42:599–606. doi: 10.1177/42.5.8157931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lecka-Czernik B, Rosen CJ. Energy excess, glucose utilization, and skeletal remodeling: new insights. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:1356–1361. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Napoli N, Chandran M, Pierroz DD, Abrahamsen B, Schwartz AV, Ferrari SL, Bone IOF, Working G. Diabetes, Mechanisms of diabetes mellitus-induced bone fragility. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:208–219. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goodman WG, Hori MT. Diminished bone formation in experimental diabetes. Relationship to osteoid maturation and mineralization. Diabetes. 1984;33:825–831. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.9.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hie M, Shimono M, Fujii K, Tsukamoto I. Increased cathepsin K and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase expression in bone of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Bone. 2007;41:1045–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shires R, Teitelbaum SL, Bergfeld MA, Fallon MD, Slatopolsky E, Avioli LV. The effect of streptozotocin-induced chronic diabetes mellitus on bone and mineral homeostasis in the rat. J Lab Clin Med. 1981;97:231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsentidis C, Gourgiotis D, Kossiva L, Doulgeraki A, Marmarinos A, Galli-Tsinopoulou A, Karavanaki K. Higher levels of s-RANKL and osteoprotegerin in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus may indicate increased osteoclast signaling and predisposition to lower bone mass: a multivariate cross-sectional analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:1631–1643. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Verhaeghe J, Suiker AM, Visser WJ, Van Herck E, Van Bree R, Bouillon R. The effects of systemic insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I and growth hormone on bone growth and turnover in spontaneously diabetic BB rats. J Endocrinol. 1992;134:485–492. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1340485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verhaeghe J, van Herck E, Visser WJ, Suiker AM, Thomasset M, Einhorn TA, Faierman E, Bouillon R. Bone and mineral metabolism in BB rats with long-term diabetes. Decreased bone turnover and osteoporosis. Diabetes. 1990;39:477–482. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kayal RA, Tsatsas D, Bauer MA, Allen B, Al-Sebaei MO, Kakar S, Leone CW, Morgan EF, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA, Graves DT. Diminished bone formation during diabetic fracture healing is related to the premature resorption of cartilage associated with increased osteoclast activity. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:560–568. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wittrant Y, Gorin Y, Woodruff K, Horn D, Abboud HE, Mohan S, Abboud-Werner SL. High d(+)glucose concentration inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. Bone. 2008;42:1122–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu F, Ye YP, Dong YH, Guo FJ, Chen AM, Huang SL. Inhibitory effects of high glucose/insulin environment on osteoclast formation and resorption in vitro. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci. 2013;33:244–249. doi: 10.1007/s11596-013-1105-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reni C, Mangialardi G, Meloni M, Madeddu P. Diabetes stimulates osteoclastogenesis by acidosis-induced activation of transient receptor potential cation channels. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30639. doi: 10.1038/srep30639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ding KH, Wang ZZ, Hamrick MW, Deng ZB, Zhou L, Kang B, Yan SL, She JX, Stern DM, Isales CM, Mi QS. Disordered osteoclast formation in RAGE-deficient mouse establishes an essential role for RAGE in diabetes related bone loss. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:1091–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou Z, Immel D, Xi CX, Bierhaus A, Feng X, Mei L, Nawroth P, Stern DM, Xiong WC. Regulation of osteoclast function and bone mass by RAGE. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1067–1080. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goettsch C, Babelova A, Trummer O, Erben RG, Rauner M, Rammelt S, Weissmann N, Weinberger V, Benkhoff S, Kampschulte M, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Hofbauer LC, Brandes RP, Schroder K. NADPH oxidase 4 limits bone mass by promoting osteoclastogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4731–4738. doi: 10.1172/JCI67603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee NK, Choi YG, Baik JY, Han SY, Jeong DW, Bae YS, Kim N, Lee SY. A crucial role for reactive oxygen species in RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Blood. 2005;106:852–859. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, O’Brien CA, Manolagas SC. Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in osteoblast precursors by diverting beta-catenin from T cell factor- to forkhead box O-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27298–27305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bai XC, Lu D, Bai J, Zheng H, Ke ZY, Li XM, Luo SQ. Oxidative stress inhibits osteoblastic differentiation of bone cells by ERK and NF-kappaB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen CT, Shih YR, Kuo TK, Lee OK, Wei YH. Coordinated changes of mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant enzymes during osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:960–968. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mody N, Parhami F, Sarafian TA, Demer LL. Oxidative stress modulates osteoblastic differentiation of vascular and bone cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:509–519. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00610-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fulzele K, Riddle RC, DiGirolamo DJ, Cao X, Wan C, Chen D, Faugere MC, Aja S, Hussain MA, Bruning JC, Clemens TL. Insulin receptor signaling in osteoblasts regulates postnatal bone acquisition and body composition. Cell. 2010;142:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ferron M, Wei J, Yoshizawa T, Del Fattore A, DePinho RA, Teti A, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and energy metabolism. Cell. 2010;142:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wei J, Ferron M, Clarke CJ, Hannun YA, Jiang H, Blaner WS, Karsenty G. Bone-specific insulin resistance disrupts whole-body glucose homeostasis via decreased osteocalcin activation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI72323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Palta M, LeCaire TJ, Sadek-Badawi M, Herrera VM, Danielson KK. The trajectory of IGF-1 across age and duration of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014;30:777–783. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao YF, Zeng DL, Xia LG, Zhang SM, Xu LY, Jiang XQ, Zhang FQ. Osteogenic potential of bone marrow stromal cells derived from streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31:614–620. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crane JL, Zhao L, Frye JS, Xian L, Qiu T, Cao X. IGF-1 signaling is essential for differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells for peak bone mass. Bone Res. 2013;1:186–194. doi: 10.4248/BR201302007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xian L, Wu X, Pang L, Lou M, Rosen CJ, Qiu T, Crane J, Frassica F, Zhang L, Rodriguez JP, Xiaofeng J, Shoshana Y, Shouhong X, Argiris E, Mei W, Xu C. Matrix IGF-1 maintains bone mass by activation of mTOR in mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:1095–1101. doi: 10.1038/nm.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang M, Xuan S, Bouxsein ML, von Stechow D, Akeno N, Faugere MC, Malluche H, Zhao G, Rosen CJ, Efstratiadis A, Clemens TL. Osteoblast-specific knockout of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor gene reveals an essential role of IGF signaling in bone matrix mineralization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44005–44012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]