Abstract

G. L. Stebbins’ most effective pollinator principle states that when pollinators are not limiting, plants are expected to specialize and adapt to the most abundant and effective pollinator species available. In this study, we quantify the effectiveness of bees, hummingbirds and hawkmoths in a Chilean population of Erythranthe lutea (Phrymaceae), and examine whether flower traits are subject to pollinator-mediated selection by the most effective pollinator species during two consecutive years. Unlike most species in the pollinator community, the visitation rate of the recently arrived Bombus terrestris did not change substantially between years, which together with its high and stable pollen delivery to flower stigmas made this species the most important in the pollinator assemblage, followed by the solitary bee Centris nigerrima. Flower traits were under significant selection in the direction expected for short-tongue bees, suggesting that E. lutea is in the initial steps of adaptation to the highly effective exotic bumblebee. Our results illustrate the applicability of Stebbins' principle for new invasive pollinators, and stress their importance in driving flower adaptation of native plant species, a critical issue in the face of biotic exchange and homogenization.

Keywords: Stebbins’ principle, invasive pollinator, pollinator-mediated selection, visitation rate, pollinator effectiveness

1. Introduction

From the early outstanding predictions including the hawkmoth with the extraordinary tongue capable of sipping nectar from the 30 cm long Malagasy star orchid tube [1], the metrical match between flower traits and suitable body parts of pollinator species has been considered as one of the most remarkable examples of fine-tuned adaptations moulded by natural selection (e.g. [2–4]). This high level of specialization is expected to evolve in plants subject to selection by abundant and effective pollinators, that is, by those pollinator species that contribute most to the mean plant population fitness. This hypothesis, known as the ‘most effective pollinator principle’ after Stebbins [5], highlights the two key components of pollinator activity that determine high levels of flower adaptation to pollinators—the frequency and effectiveness of flower visits. When these criteria are not satisfied, plants are expected to evolve generalist strategies, and lack of specialization to the most effective pollinator is expected. Most studies have hitherto examined plant adaptation and specialization in native pollination systems, where pollinators and plants have a long history of interaction [6–9]. However, the arrival and establishment of exotic pollinator species in local ecosystems may quickly shift plant traits toward new optimal states, provided exotics become more abundant and effective than native pollinators.

In this study, we examine Stebbins' principle in an Andean plant–pollinator community, where bees, hummingbirds and hawkmoths converge in the use of the Andean monkeyflower, Erythranthe lutea (Phrymaceae). In doing so, we recorded their visitation rate and the number of pollen grains deposited on virgin stigmas to estimate their effectiveness. As floral traits involved in the attraction and mechanical fit with effective pollinators are expected to be under pollinator-mediated selection, we estimated selection coefficients on flower tube length and corolla size, two floral traits often under pollinator-mediated selection [8–10].

2. Material and methods

(a). Natural history and study site

This study was performed in Juncal (32°51′ S, 70°08′ W, 2398 m elevation, Chile), during two consecutive summer seasons (2016 and 2017). Erythranthe lutea is a perennial self-compatible herb inhabiting streams and wetlands from sea level to 3650 m between 29° and 45° S. Even though E. lutea is self-compatible, pollen vectors are needed to ensure successful fertilization [10].

(b). Pollinator assemblages, pollen limitation and pollen deposition effectiveness

We recorded the mean visitation rate (VR) per pollinator species in both years. The pollen deposition effectiveness per single visit (Dv), that is, the number of pollen grains delivered by flower visitors onto virgin stigmas, was recorded by removing and storing the stigmas just visited by a pollinator in vials containing 70% ethanol. Once in the laboratory, after fixation and staining, the number of pollen grains was recorded under a binocular microscope. The pollen deposition effectiveness per unit time (Dt) for every pollinator species was calculated by multiplying VR, Dv and r, r being the proportion of flowers having receptive stigmas. All the field measurements were performed in the morning in a patch approximately 50 m2. To maximize the number of virgin stigmas, all the flowers in anthesis were removed from the patch the night before measurements, leaving only flower buds to the next morning. In consequence, we observed first-day opened flowers and the fraction of receptive flowers at the time of observation (r) was always 1 [11]. For the purposes of this study, the index Dt is appropriate as it encapsulates in one single measure the two most important factors involved in Stebbins’ principle, the frequency of visits and pollinator effectiveness.

The most effective pollinator principle states that flower evolution towards the most efficient pollinator may occur when pollen is not limited in the environment. We evaluated this criterion by estimating the pollen limitation index (L): L = 1 − (C/S), where C and S are the number of seeds produced by naturally pollinated flowers, and by flowers manually supplemented with an excess of pollen, respectively. Values near to zero indicate absence of pollen limitation in the environment. Detailed information on procedures can be found in the electronic supplementary material.

(c). Phenotypic selection

We estimated the selection coefficients of putatively functional flower traits by randomly choosing 100 plants per year and recording the mean tube length (mm) and mean corolla size (mm2) from three flowers per plant (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). At the same time when flower traits were measured, we collected three capsules from the same plant and their seed number was recorded in the laboratory to have a fitness estimate through the female sex function. The strength of pollinator-mediated selection acting upon floral traits was estimated from linear selection gradients using the multiple regression approach of Lande & Arnold [12] (see electronic supplementary material for more information).

3. Results

(a). Pollinator assemblages and visitation rate

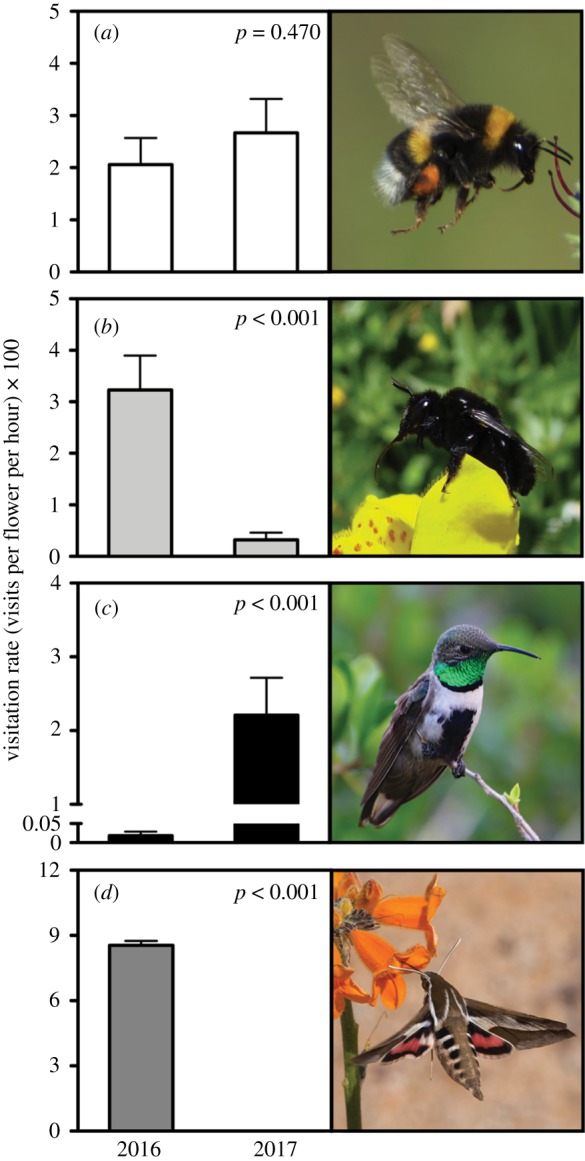

The composition of pollinator assemblages was relatively similar between years (62.5% similarity). However, when visitation rate was included in the analysis, similarity decreased to 25%, CI: 2–52% (see electronic supplementary material). This decrease was determined to a large extent by the change in visitation rate of the solitary bee Centris nigerrima, the hummingbird Oreotrochilus leucopleurus and the hawkmoth Hyles annei (figure 1 and table 1). Besides native pollinators, the exotic bumblebee Bombus terrestris has been present in the site at least since 2009, showing an increasing abundance over the years (figure 2a), as is usually observed for invasive species in the first stages of the establishment process [14,15]. This bumblebee presented a more stable pattern, making 2.06 ± 5.46 and 2.67 ± 7.31 (mean ± s.e.) visits per flower per hour in 2016 and 2017, respectively (figure 1a and table 1).

Figure 1.

Mean visitation rate (s.e.) of (a) Bombus terrestris, (b) Centris nigerrima, (c) Oreotrochilus leucopleurus and (d) Hyles annei on the Andean monkeyflower, Erythranthe lutea, during the flowering seasons of 2016 (104 h of observation) and 2017 (138 h of observation). Credit for photograph of H. annei: J. P. de la Harpe.

Table 1.

Mean visitation rate ± s.e. (Vr), pollen deposition effectiveness per single visit (Dv) and per unit time (Dt) of every flower visitor recorded on E. lutea. The nomenclature for pollen deposition effectiveness follows [11]. Numbers in parentheses in Dv-values show the number of stigmas analysed. Dashes in Dv columns indicate lack of stigmas for pollen counting, in most cases owing to low pollinator abundance. Percentages in parentheses in Dt-values represent the contribution of each pollinator species to the total on a yearly basis. Asterisks in Dt columns indicate that estimates were calculated using the Dv-value recorded in the alternative year.

| species | visitation rate (Vr, visits per flower per hour) × 100 |

pollen deposition effectiveness |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| per single visit (Dv) |

per unit time (=Dv × Vr × r) |

||||||

| 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | mean | |

| Hymenoptera | |||||||

| Bombus dahlbomii | 0.18 ± 1.05 | 0 | 345.8 ± 404.7 (8) | — | 0.64 (4.2%) | — | 0.64 (4.3%) |

| Bombus terrestris | 2.06 ± 5.46 | 2.67 ± 7.31 | 158.1 ± 260.2 (126) | 191.3 ± 292.7 (39) | 3.26 (21.4%) | 5.10 (37.0%) | 4.18 (27.9%) |

| Centris chilensis | 0.85 ± 3.12 | 0.42 ± 1.67 | 103.2 ± 207.1 (32) | 315.6 ± 658.2 (13) | 0.88 (5.8%) | 1.32 (9.6%) | 1.1 (7.4%) |

| Centris nigerrima | 3.23 ± 7.16 | 0.32 ± 1.54 | 201.1 ± 334.8 (101) | — | 6.49 (42.6%) | 0.64* (4.6%) | 3.57 (23.9%) |

| Corynura chloris | 0 | 0.01 ± 0.07 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Hypodynerus sp. | 0.004 ± 0.04 | 0.02 ± 0.10 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Megachile saulcyi | 1.33 ± 3.61 | 0.03 ± 0.13 | 112.4 ± 246.6 (52) | — | 1.50 (9.8%) | 0.03* (0.2%) | 0.77 (5.2%) |

| Megachile semirufa | 0.06 ± 0.53 | 0.04 ± 0.25 | — | 37.0 ± 25.0 (3) | 2.22* (14.6%) | 1.48 (10.7%) | 1.85 (12.4%) |

| Svastrides melanura | 0.01 ± 0.11 | 0 | 38.4 ± 33.4 (7) | — | 0.01 (0.1%) | — | 0.01 (0.1%) |

| Lepidoptera | |||||||

| Hyles annei | 8.55 ± 22.12 | 0 | 1.3 ± 6.2 (44) | — | 0.11 (0.7%) | — | 0.11 (0.7%) |

| Pseudolucia sp. | 0 | 0.004 ± 0.03 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tatochila sp. | 0.02 ± 0.17 | 0.03 ± 0.17 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Vanessa carye | 0.01 ± 0.09 | 0.01 ± 0.04 | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diptera | |||||||

| Scaeva melanostoma | 0.01 ± 0.05 | 0.01 ± 0.12 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Bombylidae | 0.02 ± 0.23 | 0 | 4 (1) | — | 0.08 (0.5%) | — | 0.08 (0.5%) |

| Apodiformes | |||||||

| Oreotrochilus leucopleurus | 0.02 ± 0.11 | 2.21 ± 6.03 | — | 236.5 ± 433.1 (48) | 0.05* (0.3%) | 5.23 (37.9%) | 2.64 (17.6%) |

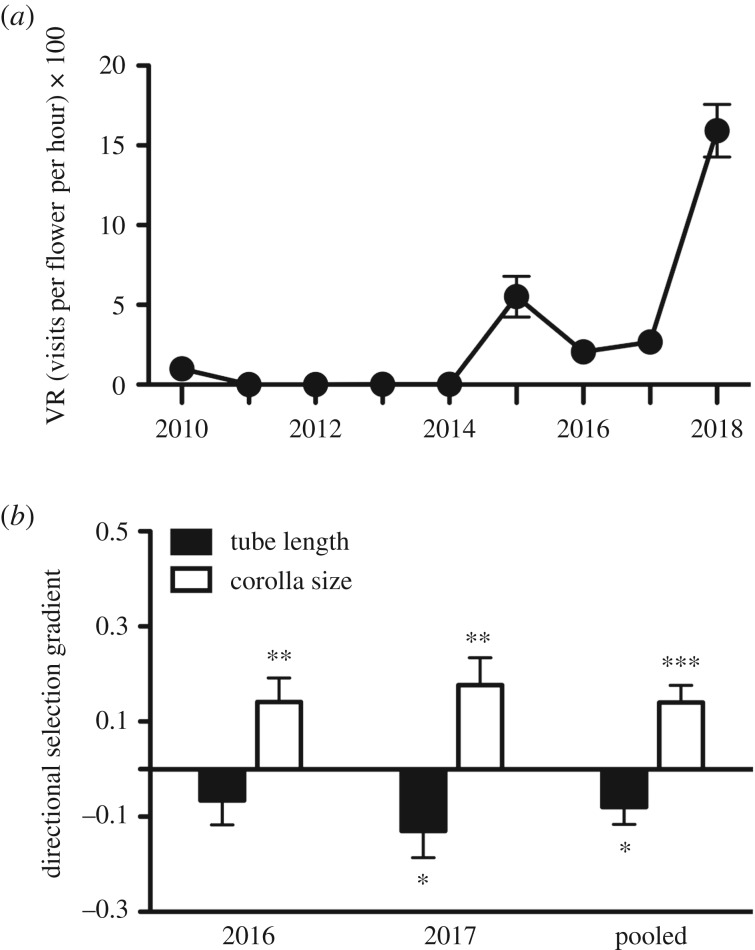

Figure 2.

(a) Pattern of temporal change in the mean (s.e.) visitation rate of Bombus terrestris during 9 consecutive years. Data from 2010 to 2012 were obtained from [13], and those from 2013 to 2018 are unpublished from a long-term research in the study site. (b) Directional selection β-coefficients (s.e.) for tube length and corolla size in 2016, 2017 and in the 2-year pooled analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(b). Pollen limitation, pollination effectiveness and natural selection

The pollen limitation index was low in the two years (2016: L = 0.28; 2017: L = 0.34) (electronic supplementary material, table S1), indicating that pollinator availability was not limiting in the study site, which satisfies an important criterion of Stebbins' principle.

The number of pollen grains delivered onto stigmas per pollinator species (Dv) and the resulting pollen deposition effectiveness (Dt) are reported in table 1. In 2016, the species with the highest Dt values were the solitary bee C. nigerrima and the exotic B. terrestris. In 2017, the most effective pollinators were the hummingbird O. leucopleurus and B. terrestris. Regarding mean effectiveness during the two years, B. terrestris was the most effective one, followed by C. nigerrima and O. leucopleurus. Likewise, the invasive bumblebee was the less variable between years (56%), followed by C. nigerrima (914%) and O. leucopleurus (19 360%), indicating that B. terrestris had not only the highest mean effectiveness but also the most stable one.

The two flower traits of E. lutea here examined were more variable between than within plants (electronic supplementary material, table S2), and represented important targets of pollinator-mediated selection (figure 2b). Pollinators were more likely to facilitate the reproduction of plants with short flower tubes in 2017 and in the 2-year pooled data (β2017 = −0.13, βpooled = −0.08). Likewise, pollinator-mediated selection consistently favoured flowers with large corollas (β2017 = 0.14, β2018 = 0.18, βpooled = 0.14).

4. Discussion

Our aim was to examine the extent to which flower traits of E. lutea were under selection by the most efficient pollinator species as predicted by Stebbins’ principle. Combining correlational and experimental approaches, we showed that the bee C. nigerrima, the hawkmoth H. annei and the hummingbird O. leucopleurus provided variable pollination service to E. lutea, in part because of their intermittent visitation rate to flowers and low effectiveness in pollen deposition. In spite of being established only in the last few years in the study site, B. terrestris was the most important pollinator for E. lutea. This observation is consistent with the selection to reduce flower tube length in the plant population. While flowers of E. lutea have a tube length of 35.8 mm on the average (N = 100 flowers), the shorter tongue length of B. terrestris (mean = 6.3 mm, range = 5.6–7.0 mm) relative to the second most important pollinator, the solitary bee C. nigerrima (mean = 9.0 mm, range = 8.2–9.8 mm), may favour short-tubed flowers as expected for bee-pollinated species [7,16]. Likewise, large corollas had a reproductive advantage over small-sized corollas. Previous evidence in this system indicates that bees visit corollas 1.25-fold larger than the hummingbird [10], which is consistent with the idea that E. lutea is in the process of adapting its flower phenotype to the effective bee pollinators. The question whether variation in the pollinator community across years reinforces the importance of B. terrestris in moulding the floral phenotype of E. lutea stresses the need for long-term studies of phenotypic selection in this system.

One important assumption of Stebbins' principle is that pollinator effectiveness is tightly coupled to the strength of pollinator-mediated selection. This assumption has been critically examined in optimality models that restrict the generality of Stebbins’ model to cases where the marginal fitness gain of specialization exceeds the marginal fitness loss of adapting to the many less efficient pollinators [17]. The relatively depauperate Chilean pollinator assemblages (4.25 pollinators per plant species on the average, [18]) offer little gain from evolving generalized flower phenotypes, and, therefore, high marginal fitness loss can be expected relative to specialization on the most effective pollinator.

Although the arrival and establishment of exotic pollinators in new environments is often associated with ecological risks and unknown detrimental consequences for local communities [19], to our knowledge their importance in driving flower adaptation of native plants has been poorly addressed in the literature [20]. This is unfortunate, as we are just beginning to understand the ecological and evolutionary consequences of invasive species in the face of biotic exchange and homogenization [14,21]. It is likely that plant phenotypic and genetic adjustments caused by recently arrived pollinators are more common than previously thought. For instance, it is now well established that evolution can occur rapidly in response to invasive species [22–24], which implies that native plant responses to highly effective exotic pollinators may occur on a time scale of a few years after their arrival and establishment in new habitats. All these facts together indicate that invasive species may, under some circumstances, become quickly the most important ones in local communities, influencing not only ecological but also evolutionary processes. Results from this study suggest that novel functional roles adopted by invasive pollinators in new habitats may be more complex than previously thought, and need to be addressed before implementation of conservation programmes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the many students and researchers who assisted with data collection. Comunidad Cano Gallegos Los Andes provided authorization to conduct the research on their land.

Ethics

This research was in accordance with the Ethics and Biosecurity protocols of the University of Chile (1809-FCS-UCH).

Data accessibility

Data are available as electronic supplementary material and in the Dryad Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.m21q0th) [25].

Authors' contributions

R.M. planned the study and wrote the paper. All authors participated in data acquisition and contributed to the manuscript, approved the final version, and are accountable for the work.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was supported by grants FONDECYT 1150112 and 1120155.

References

- 1.Darwin C. 1862. On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing. London, UK: John Murray. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson LA. 1988. The evolution of flowers with deep corolla tubes. Nature 334, 147–149. ( 10.1038/334147a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson SD, Steiner KE. 1997. Long-tongued fly pollination and evolution of floral spur length in the Disa draconis complex (Orchidaceae). Evolution 51, 45–53. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb02387.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whittall JB, Hodges SA. 2007. Pollinator shifts drive increasingly long nectar spurs in columbine flowers. Nature 447, 706–709. ( 10.1038/nature05857) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stebbins GL. 1970. Adaptive radiation of reproductive characteristics in angiosperms I: pollination mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1, 307–326. ( 10.1146/annurev.es.01.110170.001515) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayfield MM, Waser NM, Price MV. 2001. Exploring the ‘Most Effective Pollinator Principle’ with complex flowers: bumblebees and Ipomopsis aggregata. Ann. Bot. 88, 591–596. ( 10.1006/anbo.2001.1500) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenster CB, Armbruster WS, Wilson P, Dudash MR, Thomson JD. 2004. Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 35, 375–403. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132347) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexandersson R, Johnson SD. 2002. Pollinator-mediated selection on flower-tube length in a hawkmoth-pollinated Gladiolus (Iridaceae). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 631–636. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1928) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nattero J, Cocucci AA, Medel R. 2010. Pollinator-mediated selection in a specialized pollination system: matches and mismatches across populations. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 1957–1968. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02060.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medel R, Botto-Mahan C, Kalin-Arroyo M. 2003. Pollinator-mediated selection on the nectar guide phenotype in the Andean monkey flower, Mimulus luteus. Ecology 84, 1721–1732. ( 10.1890/01-0688) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ne'eman G, Jürgens A, Newstrom-Lloyd L, Potts SG, Dafni A. 2010. A framework for comparing pollinator performance: effectiveness and efficiency. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 85, 435–451. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00108.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lande R, Arnold SJ. 1983. The measurement of selection on correlated characters. Evolution 37, 1210–1226. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1983.tb00236.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esterio G, Cares-Suárez R, González-Browne C, Salinas P, Carvallo G, Medel R. 2013. Assessing the impact of the invasive buff-tailed bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) on the pollination of the native Chilean herb Mimulus luteus. Arthropod Plant Interact. 7, 467–474. ( 10.1007/s11829-013-9264-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strayer D, Eviner V, Jeschke J, Pace M. 2006. Understanding the long-term effects of species invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 645–651. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lockwood JL, Hoopes MF, Marchetti M. 2013. Invasion ecology. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faegri K, van der Pijl L. 1979. The principles of pollination ecology. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aigner PA. 2001. Optimality modeling and fitness trade-offs: when should plants become pollinator specialists? Oikos 95, 177–184. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.950121.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medel R, González-Browne C, Fontúrbel FE. 2018. Pollination in the Chilean Mediterranean-type ecosystem: a review of current advances and pending tasks. Plant Biol. 20, 89–99. ( 10.1111/plb.12644) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norfolk O, Gilbert F, Eichhorn MP. 2018. Alien honeybees increase pollination risks for range- restricted plants. Divers. Distrib. 24, 705–713. ( 10.1111/ddi.12715) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanguinetti A, Singer RB.. 2014. Invasive bees promote high reproductive success in Andean orchids. Biol. Cons. 175, 10–20. ( 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.04.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mooney HA, Cleland EE. 2001. The evolutionary impact of invasive species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5446–5451. ( 10.1073/pnas.091093398) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson JN. 1998. Rapid evolution as an ecological process. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 329–332. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01378-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hairston N, Ellner S, Geber M, Yoshida T, Fox J. 2005. Rapid evolution and the convergence of ecological and evolutionary time. Ecol. Lett. 8, 1114–1127. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00812.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuart YE, Campbell TS, Hohenlohe PA, Reynolds RG, Revell LJ, Losos JB. 2014. Rapid evolution of a native species following invasion by a congener. Science 346, 463–466. ( 10.1126/science.1257008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medel R, González-Browne C, Salazar D, Ferrer P, Ehrenfeld M. 2018. Data from: The most effective pollinator principle applies to new invasive pollinators. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.m21q0th) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available as electronic supplementary material and in the Dryad Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.m21q0th) [25].