Abstract

Striking faunal turnover across Asia and Australasia, most famously along the eastern edge of the Sunda Shelf or ‘Wallace's Line’, has been a focus of biogeographic research for over 150 years. Here, we investigate the origins of a highly threatened endemic lizard fauna (four species) on Christmas Island. Despite occurring less 350 km south of the Sunda Shelf, this fauna mostly comprises species from clades centred on the more distant regions of Wallacea, the Pacific and Australia (more than 1000 km east). The three most divergent lineages show Miocene (approx. 23–5 Ma) divergences from sampled relatives; and have recently become extinct or extinct in the wild, likely owing to the recent introduction of a southeast Asian snake (Lycodon capucinus). Insular distributions, deep phylogenetic divergence and recent decline suggest that rather than dispersal ability or recent origins, environmental and biotic barriers have impeded these lineages from diversifying on the continental Sunda Shelf, and thereby, reinforced faunal differentiation across Wallace's Line. Our new phylogenetically informed perspective further highlights the rapid loss of ancient lineages that has occurred on Christmas Island, and underlines how the evolutionary divergence and vulnerability of many island-associated lineages may continue to be underestimated.

Keywords: extinction, phylogenetic distinctiveness, Sunda Shelf, Wallace's Line, Wallacea

1. Introduction

For over 150 years, biogeographers have noted marked biotic turnover between the Asian and Australian regions. This is most striking at the transition between the eastern edge of the Sunda Shelf and the islands of Wallacea (the Lesser Sundas and Sulawesi) [1], now widely referred to as Wallace's Line. This turnover has been linked to the former isolation and disjunct history of the Asian and Australian continental plates [2]. However, other factors such as biotic interactions (e.g. competition and predation) or environmental gradients may also underpin spatial variation in phylogenetic and evolutionary diversity [3,4]. For instance, downstream colonizations from the Sunda Shelf and into Australasia outnumber upstream colonizations [5,6], suggesting more species-rich and stable Sunda communities have been more resistant to biotic invasion.

Christmas Island is the westernmost oceanic island in the Australasian region. This isolated seamount (135 km2) lies over 1000 km west of mainland Australia and Wallacea, and 350 km south of Java in the Indian Ocean (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Shortly after human settlement in the late 1880s, a diverse endemic fauna was documented [7], providing an exceptional baseline to study subsequent biotic change. While most endemic birds persist, the terrestrial reptile and mammal fauna have been severely depleted; four of five endemic mammals are extinct [8], as are three of the five reptiles (although two persist as ex situ captive colonies), with the reptile extinctions all occurring since 2009 [9]. Temporal and spatial patterns of decline of the reptile fauna strongly suggest the key cause was a primarily lizard eating snake (Lycodon capucinus) recently introduced from Asia, and also linked to extinctions of endemic lizard species in other islands in the Indian Ocean (see the electronic supplementary material, references). However, despite the isolation and conservation significance of this lizard fauna, its biogeographic origins remain unassessed.

Here, we show that four (of the five) endemic Christmas Island reptile species are nested within radiations centred on Wallacea, Australia or the Pacific (table 1). Phylogenetic and distributional data indicate the relevant clades have histories of persistence and/or dispersal on islands around the Sunda Shelf since the Miocene, but have been largely unable to colonize the shelf itself. Coupled with recent Lycodon driven extinctions, this suggests that biotic interactions or other environmental barriers, rather than dispersal ability, may underpin the contemporary rarity of these taxa on large landmasses west of Wallace's Line.

Table 1.

Summary of biogeographic associations and divergence times for Christmas Island endemic lizards. Preferred model = combination molecular rate and speciation models with highest marginal likelihood. Ma, millions of years ago; HPD, highest posterior density; strict, strict clock rate model; lgnm, lognormal rate model; BD, birth–death speciation model; Yule, Yule speciation model.

| preferred models | sister lineage/nearest relatives | posterior support | location of nearest relative | mean split (Ma) | 95% HPD (Ma) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyrtodactylus sadleiricombined datacombined no 3rds | lgnm + Yule | Cyrtodactylus sp. Bali | 0.99 | Bali | 1 | 1–2 |

| lgnm + BD | Cyrtodactylus sp. Bali | 0.71 | Bali | 2 | 1–3 | |

| Lepidodactylus listericombined datacombined no 3rdsnuclear data only | strict + BD | Lepidodactylus lugubris group + Luperosaurus joloensis | 0.77/07a | Philippines | 23–26a | 19–32a |

| lgnm + BD | Lepidodactylus lugubris group | 0.95 | Philippines | 26 | 21–31 | |

| lgnm + BD | Lepidodactylus lugubris group | 1.00 | Philippines | 28 | 22–34 | |

| Emoia nativitatismtDNA | strict + Yule | Emoia boettgeri | 1.00 | Micronesia | 13 | 9–18 |

| Cryptoblepharus egeriaemtDNA | strict + Yule | Cryptoblepharus metallicus group | 1.00 | Australia | 7 | 5–10 |

aBasal relationships poorly supported, posterior support and divergence estimates spanning two most closely related lineages shown.

2. Methods

We compiled sequence data for four (out of five) endemic reptile species from Christmas Island; two skinks Cryptoblepharus egeriae (Extinct in the Wild) and Emoia nativitatis (Extinct), and two geckos Cyrtodactylus sadleiri (Endangered) and Lepidodactylus listeri (Extinct in the Wild) (status from 2017 IUCN assessments). Tissues are not available for a very rare endemic blindsnake Ramphotyphlops exocoeti (Data Deficient) and from the Christmas Island population of the other native reptile, the non-endemic skink Emoia atrocostata, whose Christmas Island population was recently extirpated. For each genus, alignments included recognized species and divergent but taxonomically unrecognized lineages, mostly from published studies [10–12] (electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S4). Dated phylogenies were estimated using Bayesian approaches [13] run for 20 000 000 generations, sampling every 20 000, with the first 20% of trees discarded as burn-in.

Gecko analyses used secondary age priors for intrageneric nodes (electronic supplementary material, table S2) derived from a fossil-calibrated five nuclear gene alignment spanning gekkotans (electronic supplementary material, figure S2), and were run on combined datasets with, and without, third codons. One gecko lineage (Lepidodactylus) showed a very deep split from other sampled taxa, so additional nuclear gene analyses were run to assess robustness of age inference. A reliable and dated overall family level tree for skinks is not available [14], so we combined (a) broad mitochondrial rate-based calibrations and (b) age priors from a rate-smoothed chronogram for the relevant clade (the Eugongylus group) (electronic supplementary material, methods). Alignments and .xml files are available online [15].

3. Results and discussion

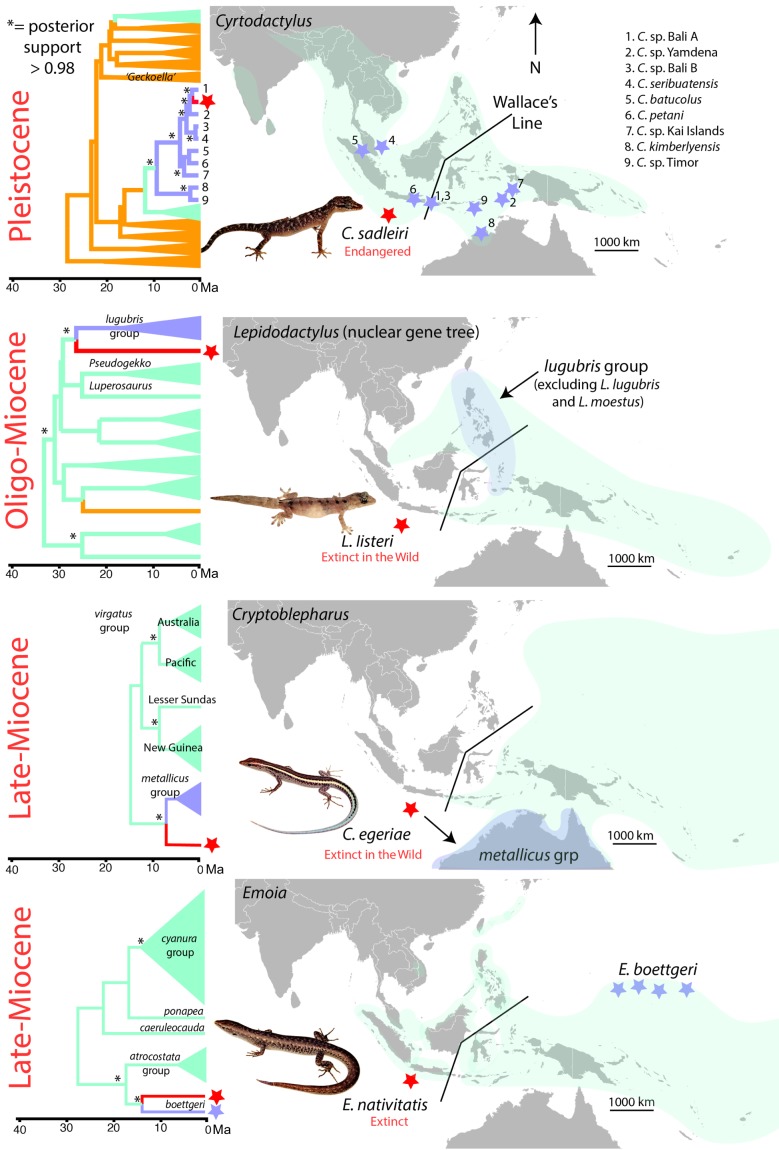

All Christmas Island endemic lizards have biogeographic affinities with radiations centred to the east of Wallace's Line (figure 1). The three extinct, or extinct in the wild, species are most genetically divergent (approx. 5–25 Myr separation from closest sampled relatives) and geographically disjunct, associating with lineages centred in mainland Australia (Cryptoblepharus; approx. 1500 km), The Philippines (Lepidodactylus; approx. 2500 km) and Micronesia (Emoia; approx. 4000 km). One species still extant in the wild, Cyrtodactylus sadleiri, is less divergent, and closely related to taxonomically unassigned populations from Bali (approx. 1000 km east) and Yamdena (approx. 3000 km east). Genetic divergences at the ND2 locus between these lineages (0.043–0.063% pairwise uncorrected) are low for gecko species [16]. These lineages sit within a broader late Miocene radiation centred on Wallacea, from which several dispersals westwards onto islands and other coastal or savannah habitats around the edge of the Sunda Shelf are inferred [17].

Figure 1.

Biogeographic relationships and temporal divergence of endemic Christmas Island lizards. Taxa from Christmas Island (red star); sister lineages or closest relatives (light blue); overall natural distribution of congeners (light green). Lineages from the Sunda Shelf or mainland Asia are orange.

As-yet-unsampled taxa could split key branches in our phylogenies and reduce the phylogenetic distinctiveness that we report for the Christmas Island endemics (electronic supplementary material, further discussion). However, very few taxa in these relevant clades are currently known from the Sunda Shelf, so the broad pattern that all Christmas Island endemics are derived from clades centred east of Wallace's Line is likely to be robust. A converse possibility that one or more of the Christmas Island taxa have anthropogenic origins seems unlikely: none is human commensal; divergences pre-date anthropogenic movement across Wallacea, and all were collected prior to or within 10 years of the island's original settlement [7].

All four lizard radiations with endemic taxa on Christmas Island have a long history in regions east (Wallacea) and south (Christmas Island and/or Australia) of the Sunda Shelf, and show evident overwater dispersal ability (three of the genera also have naturally dispersed thousands of kilometres eastwards into the Pacific, or westwards to the Malagasy region [18]). It is, therefore, striking that they are only marginally present on the Sunda Shelf (absent from rainforest, and restricted to coastal or savannah habitats) [19]. The introduction (in the 1980s) of a predatory genus (Lycodon) widespread on the Sunda Shelf is also presumed to have caused the recent loss of the three most phylogenetically divergent Christmas Island taxa [9], as well as the Christmas Island populations of the widespread insular lizard Emoia atrocostata. Other insular associated lizard [20] and bird [4] radiations that are widespread in Wallacea also show distributional boundaries along the eastern edge of the Sunda Shelf, while ranging widely into Melanesia and the Pacific. Insular distributions and biotic vulnerability are often linked to the loss of key traits subsequent to colonization of simple, isolated and benign island communities (e.g. flightlessness) [21]. Our results suggest a converse idea that along the edge of the Sunda Shelf or ‘Wallace's Line’ sharp distributional turnover linked to dispersal limitations in continental taxa [1,4] may be further reinforced by an inability of island-associated radiations to successfully penetrate (or persist in) complex continental systems.

Phylogenetic analyses continue to reveal divergent endemic lineages on other relatively small islands across the Indo-Pacific [12], and elsewhere [22]. The study of such highly isolated biotas can provide an important perspective on the underlying mechanisms that explain contemporary biogeographic distributions. However, unfortunately, while—by definition—many island relicts have persisted over very long periods, many fare poorly when new competitors and predators are anthropogenically introduced [21]. In such cases, millions of years of unique evolutionary history may be lost with extraordinary rapidity. Christmas Island provides an unusually well-documented case study, and we estimate that the three recently extinct species (including the two extinct in the wild) each represented millions of years of unique evolutionary history. Therefore, maintenance and enhancement of conservation management of Christmas Island's two endemic lizard species now occurring only as captive populations should remain a priority [23]. More broadly, it seems likely that similar declines or extinctions on islands across the Indian Ocean and Pacific may have gone unrecorded, and further, that other similarly divergent and vulnerable taxa may remain extant, but undocumented. We suggest that there is a priority research need to document endemic island faunas, to understand their evolutionary significance and phylogenetic distinctiveness, and to try to enforce better biosecurity protocols to halt the ongoing spread of L. capucinus [24] and other taxa [25] that could devastate some of their most evolutionarily distinctive endemic species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Chris Austin, Rafe Brown, Steve Donnellan, Bee Gunn, Fred Kraus, Cameron Siler, Scott Travers and Andrew Hugall provided tissues and sequence data. Patrick Campbell (BMNH) provided photographs of types. The use of trade, product or firm names in this publication does not imply endorsement by the US Government. Parks Australia facilitated study and collection of material on Christmas Island.

Ethics

This work was undertaken in support of Parks Island and Biodiversity Science Branch, Department of the Environment and Energy, Canberra and in collaboration with the staff of Christmas Island National Park.

Data accessibility

Specimen details are provided in the electronic supplementary material. All supplementary material and alignments are available on Dryad (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s66p0) [15].

Authors' contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and to drafting and revising the paper, and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be held accountable for the content therein.

Competing interests

We declare no competing interests.

Funding

This project was supported by the Australian Research Council (grant no. DE140100220) DECRA fellowship to P.M.O., and Laureate Fellowship to Craig Moritz. R.N.F. and J.Q.R. thank the USGS Ecosystems Mission Area for funding and project support.

References

- 1.Wallace AR. 1860. On the zoological geography of the Malay archipelago. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 4, 172–184. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keast A. 1981. Origins and relationships of the Australian biota. In Ecological biogeography of Australia (ed. Keast A.), pp. 1999–2059. The Hague, The Netherlands: FW Junk. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliver PM, Skipwith P, Lee MSY. 2014. Crossing the line: increasing body size in a trans-Wallacean lizard radiation (Cyrtodactylus, Gekkota). Biol. Lett. 10, 20140479 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0479) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dekker RWRJ. 1989. Predation and the western limits of megapode distribution (Megapodiidae; Aves). J. Biogeogr. 16, 317–321. ( 10.2307/2845223) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver PM, Hugall AF. 2017. Phylogenetic evidence for mid-Cenozoic turnover of a diverse continental biota. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1896–1902. ( 10.1038/s41559-017-0355-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crayn DM, Costion C, Harrington MG. 2015. The Sahul–Sunda floristic exchange: dated molecular phylogenies document Cenozoic intercontinental dispersal dynamics. J. Biogeogr. 42, 11–24. ( 10.1111/jbi.12405) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews CW. 1900. The geographical relations of the flora and fauna of Christmas Island. In A monograph of Christmas Island (ed. Andrews C.), pp. 229–317. London, UK: British Museum of Natural History. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woinarski JCZ, Burbidge AA, Harrison PL. 2015. Ongoing unraveling of a continental fauna: decline and extinction of Australian mammals since European settlement. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 4531–4540. ( 10.1073/pnas.1417301112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith MJ, Cogger H, Tiernan B, Maple D, Boland C, Napier F, Detto T, Smith P. 2012. An oceanic island reptile community under threat: the decline of reptiles on Christmas Island, Indian Ocean. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 7, 206–218. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliver PM, Richards SJ, Sistrom M. 2012. Phylogeny and systematics of Melanesia's most diverse gecko lineage (Cyrtodactylus, Gekkonidae, Squamata). Zool. Scr. 41, 437–454. ( 10.1111/j.1463-6409.2012.00545.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blom MPK, Horner P, Moritz C. 2016. Convergence across a continent: adaptive diversification in a recent radiation of Australian lizards. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20160181 ( 10.1098/rspb.2016.0181) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein ER, Harris RB, Fisher RN, Reeder TW. 2016. Biogeographical history and coalescent species delimitation of Pacific island skinks (Squamata: Scincidae: Emoia cyanura species group). J. Biogeogr. 43, 1917–1929. ( 10.1111/jbi.12772) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. 2012. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1969–1973. ( 10.1093/molbev/mss075) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Title PO, Rabosky DL. 2017. Do macrophylogenies yield stable macroevolutionary inferences? An example from squamate reptiles. Syst. Biol. 66, 843–856. ( 10.1093/sysbio/syw102) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliver PM, Blom MPK, Cogger HG, Fisher RN, Richmond JQ, Woinarski JCZ. 2018. Data from: Insular biogeographic origins and high phylogenetic distinctiveness for a recently depleted lizard fauna from Christmas Island, Australia. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.s66p0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Oliver PM, Adams M, Lee MSY, Hutchinson MN, Doughty P. 2009. Cryptic diversity in vertebrates: molecular data double estimates of species diversity in a radiation of Australian lizards (Diplodactylus, Gekkota). Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 2001–2007. ( 10.1098/rspb.2008.1881) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood PL, Heinicke MP, Jackman TR, Bauer AM. 2012. Phylogeny of bent-toed geckos (Cyrtodactylus) reveals a west to east pattern of diversification. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 65, 992–1003. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocha S, Carretero MA, Vences M, Glaw F, James Harris D. 2006. Deciphering patterns of transoceanic dispersal: the evolutionary origin and biogeography of coastal lizards (Cryptoblepharus) in the western Indian Ocean region. J. Biogeogr. 33, 13–22. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01375.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grismer LL. 2011. Lizards of peninsula Malaysia, Singapore and their adjacent archipelagos. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Edition Chimaira. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linkem CW, et al. 2013. Stochastic faunal exchanges drive diversification in widespread Wallacean and Pacific island lizards (Squamata: Scincidae: Lamprolepis smaragdina). J. Biogeogr. 40, 507–520. ( 10.1111/jbi.12022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steadman DW. 2006. Extinction and biogeography of tropical Pacific birds. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Townsend TM, Tolley KA, Glaw F, Bohme W, Vences M. 2011. Eastward from Africa: palaeocurrent-mediated chameleon dispersal to the Seychelles islands. Biol. Lett. 7, 225–228. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0701) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrew P, et al. 2018. Somewhat saved: a captive breeding programme for two endemic Christmas Island lizard species, now extinct in the wild. Oryz 52, 171–174. ( 10.1017/S0030605316001071) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuch U, McGuire J. 2004. Range extensions of Lycodon capucinus BOIE 1827 in eastern Indonesia. Herpetozoa 17, 191–193. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reilly S, Wogan G, Stubbs A, Arida E, Iskandar D, McGuire J. 2017. Toxic toad invasion of Wallacea: a biodiversity hotspot characterized by extraordinary endemism. Glob. Chang. Biol. 23, 5029–5031. ( 10.1111/gcb.13877) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Oliver PM, Blom MPK, Cogger HG, Fisher RN, Richmond JQ, Woinarski JCZ. 2018. Data from: Insular biogeographic origins and high phylogenetic distinctiveness for a recently depleted lizard fauna from Christmas Island, Australia. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.s66p0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Specimen details are provided in the electronic supplementary material. All supplementary material and alignments are available on Dryad (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s66p0) [15].