Abstract

Three ferric dipyrromethene complexes featuring different ancillary ligands were synthesized by one electron oxidation of ferrous precursors. Four-coordinate iron complexes of the type (ArL)FeX2 [ArL = 1,9-(2,4,6-Ph3C6H2)2-5-mesityldipyrromethene] with X = Cl or tBuO were prepared and found to be high-spin (S = 5/2), as determined by superconducting quantum interference device magnetometry, electron paramagnetic resonance, and 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy. The ancillary ligand substitution was found to affect both ground state and excited properties of the ferric complexes examined. While each ferric complex displays reversible reduction and oxidation events, each alkoxide for chloride substitution results in a nearly 600 mV cathodic shift of the FeIII/II couple. The oxidation event remains largely unaffected by the ancillary ligand substitution and is likely dipyrrin-centered. While the alkoxide substituted ferric species largely retain the color of their ferrous precursors, characteristic of dipyrrin-based ligand-to-ligand charge transfer (LLCT), the dichloride ferric complex loses the prominent dipyrrin chromophore, taking on a deep green color. Time-dependent density functional theory analyses indicate the weaker-field chloride ligands allow substantial configuration mixing of ligand-to-metal charge transfer into the LLCT bands, giving rise to the color changes observed. Furthermore, the higher degree of covalency between the alkoxide ferric centers is manifest in the observed reactivity. Delocalization of spin density onto the tert-butoxide ligand in (ArL)FeCl(OtBu) is evidenced by hydrogen atom abstraction to yield (ArL)FeCl and HOtBu in the presence of substrates containing weak C–H bonds, whereas the chloride (ArL)FeCl2 analogue does not react under these conditions.

Graphical Abstract

1.0. INTRODUCTION

During the past decade, a renewed interest in late, first-row transition-metal complexes as catalysts for C–H activation has emerged.1 In many cases, high-spin states, resulting from compressed ligand fields, have been implicated as essential features for the unique reactivity observed.2 Specifically, ancillary or spectator ligands have a pronounced influence on the electronic structure, induce orbital rearrangements, and influence bonding interactions between the metal and ligands.3 Attenuated ligand field environments favor complexes with maximum multiplicity and render the resulting metal complexes highly electrophilic.4 While high-spin, electron-poor transition metals act as potent Lewis acids, accepting electron density from bound ligands, they in turn can confer radical spin density upon the ligand.5 In these cases, it is essential to understand how communication between metal center and ligand can change the electronic structure and therefore the reactivity of the complex.

We previously reported the synthesis of ferrous dipyrrinato complexes that feature compressed ligand fields, resulting in high-spin states.2a,b,6 Oxidation of the ferrous dipyrrin precursors with aryl azides resulted in the formation of high-spin (S = 2) FeIII iminyl complexes.2a,b These species are best described as high-spin ferric centers antiferromagnetically coupled to an iminyl ligand-based radical, an assignment supported by 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy and electronic structure calculations.

To better understand how the electronic structure of a high-spin metal center can influence and be influenced by ancillary ligand substitutions, we explored single electron oxidation of a selection of ferrous precursors bearing different supporting ligands. Specifically, this study intends to address the following outstanding questions: how does ancillary ligand substitution impact (1) the resulting electronic structure, (2) molecular redox behaviors, (3) excited state phenomena, (4) ligand character contribution into the frontier orbitals, and (5) the resultant molecular reactivity profiles? Herein, we report the synthesis of a family of ferric compounds supported by the dipyrrinato ligand platform with varying ancillary ligand substitution to address the foregoing questions.

2.0. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

For general procedures and methods, see the Supporting Information.

Synthesis of [nBu4N][(ArL)FeCl2] (2)

In a 20 mL vial, tetrabutylammonium chloride (82 mg, 0.31 mmol, 3.0 equiv) was suspended in 2 mL of benzene. A solution of (ArL)FeCl (1) (0.1 g, 0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in 5 mL of benzene was added while stirring. After being stirred at room temperature for 3 h, the reaction solution was filtered through Celite, and the filter cake was washed with excess benzene until the eluent was nearly colorless. The solvent was frozen and removed in vacuo to yield [nBu4N][(ArL)FeCl2] (2) as a purple powder (0.10 g, 99%). Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from a concentrated solution of toluene layered with hexanes at −35 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, 295 K, C6D6): δ 40.68, 19.71, 13.78, 12.17, 11.62, 8.55, 7.64, 7.31, 7.00, 5.11, 4.98, 4.56, 3.98, 3.70, 2.42, −7.38. χMT (295 K, SQUID) = 2.9 cm3K/mol. Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer (90 K) (δ, |ΔEQ| (mm/s)): 0.94, 3.29 (γ = 0.18 mm/s). %CHN Calcd for C82H85Cl2FeN3: C, 79.47; H, 6.91; N, 3.39; Found: C, 79.48; H, 6.97; N, 3.53.

Synthesis of (ArL)FeCl2 (4)

In a 20 mL vial, ferrocenium hexafluorophosphate (52 mg, 0.16 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was frozen in 3 mL of benzene. A just-thawed solution of [nBu4N][(ArL)-FeCl2] (2) in 5 mL of benzene (0.20 g, 0.16 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added while stirring. The mixture was thawed and stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite, and the filter cake was washed with excess benzene until the eluent was nearly colorless. The solvent was frozen and removed in vacuo to yield a brown powder. The residue was washed with hexanes (5 × 3 mL) and recrystallized at −35 °C from 12 mL of 3:1 ratio of hexanes to toluene. The following morning, the mother liquor was decanted, and the crystals were washed with 2 mL of hexanes and dried in vacuo to afford (ArL)FeCl2 (4) as green crystals (72 mg, 73%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, 295 K, C6D6): δ 91.80 (bs), 13.70 (bs). χMT (295 K, SQUID) = 4.1 cm3K/mol. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (toluene, 77 K): geff = 8.40, 5.45, 2.95. Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer (90 K) (δ, |ΔEQ| (mm/s)): 0.23, 0; Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer (4 K) (δ, |ΔEQ| (mm/s)): 0.10, 0.21. % CHN Calcd for C66H49Cl2FeN2: C, 79.52; H, 4.95; N, 2.81; Found: C, 79.56; H, 4.77; N, 2.84.

Synthesis of (ArL)FeCl(OtBu) (5)

In a 20 mL vial, (ArL)FeCl (1) (0.11 g, 0.11 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was frozen in 4 mL of benzene. A just-thawed solution of di-tert-butyl peroxide (42 mg, 0.29 mmol, 2.5 equiv) in 4 mL of benzene was added while stirring. The mixture was thawed and stirred at room temperature for 12 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite, and the filter cake was washed with excess benzene until the eluent was nearly colorless. The solvent was frozen and removed in vacuo to yield a purple powder. The residue was recrystallized at −35 °C from a 3:1 ratio of hexanes to toluene. The following morning, the mother liquor was decanted, and the crystals washed with 2 mL of hexanes and dried in vacuo to afford (ArL)FeCl(OtBu) (5) as purple crystals (78 mg, 66%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, 295 K, C6D6): δ 93.2 (bs), 39.4 (bs), 17.7 (bs). χMT (295 K, SQUID) = 3.96 cm3K/mol. EPR (toluene, 77 K): geff = 6.77, 5.87, 5.12, 1.96. Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer (4 K) (δ, |ΔEQ| (mm/s)): 0.32, 1.31 (γ = 0.45 mm/s). %CHN Calcd for C70H58ClFeN2O: C, 81.27; H, 5.65; N, 2.71; Found: C, 81.24; H, 5.77; N, 2.95.

Synthesis of K[(ArL)Fe(OtBu)2] (3)

In a 20 mL vial, potassium tert-butoxide (35 mg, 0.31 mmol, 3.0 equiv) was suspended in 4 mL of benzene. A solution of (ArL)FeCl (1) in 6 mL of benzene (0.1 g, 0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added while stirring. After being stirred at room temperature for 3 h, the reaction mixture was filtered through Celite, and the filter cake was washed with excess benzene until the eluent was nearly colorless. The solvent was frozen and removed in vacuo to yield K[(ArL)Fe(OtBu)2] (3) as an orange-red powder (0.12 g, quant.) Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from a concentrated solution of toluene layered with hexanes at −35 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, 295 K, C6D6): δ 27.16, 15.86, 12.73, 11.95, 11.21, 9.17, 7.75, 7.52, 6.43, 6.30, 5.98, 5.37, 3.59, 2.38, 2.00, 1.67, 1.42, 1.21. 0.00, −2.30. Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer (90 K) (δ, |ΔEQ| (mm/s)): 0.97, 1.72 (γ = 0.21 mm/s). %CHN Calcd for KC74H67FeN2O2: C, 79.98; H, 6.08; N, 2.52; Found: C, 79.85; H, 5.97; N, 2.50.

Synthesis of (ArL)Fe(OtBu)2 (6)

In a 20 mL vial, K[(ArL)Fe(OtBu)2] (3) (0.12 g, 0.11 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was frozen in 4 mL of THF. A just-thawed solution of silver tetrafluoroborate in 4 mL of THF (0.20 g, 0.22 mmol, 2.0 equiv) was added while stirring. The mixture was thawed and stirred at room temperature for 10 min. The reaction mixture was concentrated, dissolved in benzene, and filtered through Celite, and the filter cake was washed with excess benzene until the eluent was nearly colorless. The solvent was frozen and removed in vacuo to yield a red-pink powder. The filtration in benzene was repeated to remove traces of silver. The residue was washed with 3 mL of hexanes and recrystallized at −35 °C from a 4:1 ratio of hexanes to benzene. The following morning, the mother liquor was decanted, and the crystals were dried in vacuo to afford (ArL)Fe(OtBu)2 (6) as metallic-red crystals (75 mg, 65%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, 295 K, C6D6): δ 89.9 (bs), 39.9 (bs), 25.3 (bs), 11.1 (bs). χMT (295 K, SQUID) = 3.93 cm3K/mol. EPR (toluene, 77 K): geff = 7.48, 5.73, 4.25, 1.81. Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer (4 K) (δ, |ΔEQ| (mm/s)): 0.33, 1.53 (γ = 0.63 mm/s). %CHN Calcd for C74H67FeN2O2: C, 82.90; H, 6.30; N, 2.61; Found: C, 82.68; H, 6.44; N, 2.64.

3.0. RESULTS

3.1. Synthesis of Fe Complexes

The ferrous precursor (ArL)FeCl (1) [ArL = 1,9-(2,4,6-Ph3C6H2)2-5-mesityldipyrromethene] was synthesized according to literature procedures.2a Two oxidation procedures were attempted: (a) anion coordination followed by outer-sphere oxidation and (b) inner-sphere oxidation using an appropriate oxidant. The addition of excess tetrabutylammonium chloride (3 equiv) to 1 in a benzene solution at room temperature affords the four-coordinate ferrous salt [nBu4N][(ArL)FeCl2] (2) following filtration to remove excess tetrabutylammonium chloride. Red crystals of 2 were isolated upon crystallization from toluene/hexanes at −35 °C, and the structure was obtained by single crystal X-ray crystallography (Figure S-22). Paramagnetic 2 was analyzed by 1H NMR and displays shifts consistent with those of other four-coordinate ferrous dipyrrin complexes.2a,b Oxidation of 2 with one equivalent of ferrocenium hexa-fluorophosphate at room temperature in benzene results in an instantaneous color change from red to dark brown. Isolation from the ferrocene byproduct yielded a green solid. Recrystallization of the solid from a mixture of toluene and hexanes afforded green crystals of the ferric complex (ArL)FeCl2 (4) in 73% yield (Scheme 1). The 1H NMR spectrum of 4 exhibits only two very broad peaks at 91.8 and 13.7 ppm.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of FeIII Complexes Supported by a Dipyrrinato Ligand

The addition of excess potassium tert-butoxide (3 equiv) to 1 in a benzene solution at room temperature affords the four-coordinate salt K[(ArL)Fe(OtBu)2] (3) as an orange powder after filtration and lyophilization. The solid state molecular structure shows that the potassium counterion is coordinated to two of the dipyrrin-flanking phenyl rings (Figure S-25).7 Reaction of 3 with a just-thawed solution of silver tetrafluoroborate (1 equiv) in THF precipitates a silver mirror over the course of 10 min. The solid byproducts were removed by repeated filtration, and the remaining product was purified via recrystallization from benzene/hexanes to afford orange-red crystals of (ArL)Fe(OtBu)2 (6) in 65% yield.

The reaction of 1 with potassium tert-butoxide leads to rapid oversubstitution of alkoxide, making the mixed ancillary anion [(ArL)FeCl(OtBu)]− inaccessible. Gratifyingly, treatment of 1 with di-tert-butyl peroxide at room temperature in benzene afforded a dark purple solution distinct from 1, as ascertained by 1H NMR. Crystallization of the new material from toluene/hexanes provides analytically pure (ArL)FeCl(OtBu) (5) as purple crystals.

3.2. Crystal Structure Analysis of 4–6

Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were typically grown from hexane-layered toluene solutions at −35 °C. The solid-state molecular structures of 4–6 are depicted in Figure 1 with the pertinent metrical parameters listed in Table 1. The Fe–N bond distances for the oxidized complexes are contracted compared to FeII precursors. For example, the Fe–N distances decrease by 5.4 and 5.8% upon oxidation of 2 to 4, respectively (2: Fe–N1 2.089(3) Å, Fe–N2 2.089(3) Å; 4: Fe–N1 1.967(2) Å, Fe–N2 1.966(2) Å). The iron center is raised above the dipyrrin ligand platform in all complexes, and the geometry is best described as between trigonal-pyramidal and tetrahedral with 2 and 4 having nearly perfect trigonal-pyramidal structures (τ4 = 0.84 for 2, τ4 = 0.86 for 4).8 The geometries of 5 and 6 are closer to tetrahedral, possibly due to steric pressure from the tert-butoxide substituents. The dipyrrin platform is nearly planar in 4 and 6, but a substantial distortion from planarity has occurred in 5. The distortion of the ligand can be described by the Cα–N–N–Cα torsion angle, which has been used as a measure of ruffling in porphyrin systems.9 The dipyrrin torsion angle in 5 is 20.48(1)° and might be due to crystal packing effects.

Figure 1.

Solid-state molecular structures for (a) (ArL)FeCl2 (4), (b) (ArL)FeCl(OtBu) (5), and (c) (ArL)Fe(OtBu)2 (6) at 100 K with thermal ellipsoids at 50% probability level for 4 and 6 and at 30% probability level for 5. Color scheme: C, gray; N, blue; Cl, green; O, red; Fe, orange. H atoms and solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity.

Table 1.

Selected Bond Distances and Angles for Compounds 2 and 4–6a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| bond (Å)/angle (deg) | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Fe1–N1 | 2.089(3) | 1.967(2) | 2.031(4) | 2.0253(18) |

| Fe1–N2 | 2.086(3) | 1.966(2) | 1.985(4) | 2.0243(19) |

| Fe1–X1 | 2.2689(11) | 2.1703(7) | 2.2258(16) | 1.7936(16) |

| Fe1–X2 | 2.3027(10) | 2.1890(7) | 1.785(3) | 1.7967(19) |

| τ4b | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| <(Cα–N1–N2–Cα) | 11.065(2) | 0.60814(4) | 20.48(1) | 1.67487(2) |

3.3. Oxidation State Determination

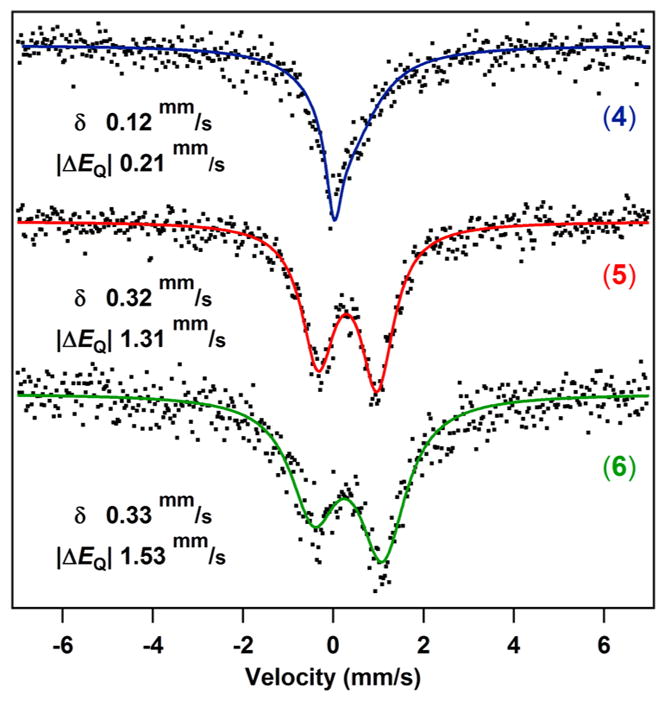

Oxidation changes from the ferrous (2 and 3) precursor to the ferric (4–6) products were ascertained using zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy. Complexes 2 and 3 exhibit single quadrupole doublets in their 57Fe Mössbauer spectra at 90 K with isomer shifts (δ) of 0.94 and 0.97 mm/s and quadrupole splittings (|ΔEQ|) of 3.29 and 1.72 mm/s, respectively (Table 2, Figures S-3 and S-4). These values are typical for four-coordinate high-spin FeII complexes.10

Table 2.

Spectroscopic Parameters Measured by 57Fe Mössbauer Spectroscopy at 90 K, χMT at Room Temperature Derived from the Magnetization Measurements with Fitting Parameters, and UV/Vis Parametersa

| δ (mm/s) | |ΔEQ| (mm/s) | Γfwhm (mm/s) | χMT (RT) (cm3K/mol) | g value | D (cm−1) | |E/D| | λmax(nm) | ε (M−1 cm−1) 103 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 556 | 64.4 | |||||||

| 2 | 0.94 (0.94) | 3.29 (3.31) | 0.18 | 2.88 | 2.13 | −12.43 | 0.3 | 530 | 71.6 |

| 3 | 0.97 (1.03) | 1.72 (1.53) | 0.21 | 531 | 67.8 | ||||

| 4b | 0.12 (0.23) | 0 (−0.40) | 0.64 | 4.07 | 1.96 | 1.82 | 0 | 469 | 19.0 |

| 5b | 0.32 (0.30) | 1.31 (−1.54) | 0.45 | 3.96 | 1.90 | 1.28 | 0 | 562 | 31.6 |

| 6b | 0.33 (0.35) | 1.53 (−1.22) | 0.63 | 3.93 | 1.89 | 0.99 | 0 | 532 | 53.4 |

Experimental (calculated).

57Fe Mössbauer spectra were recorded at 4 K.

57Fe Mössbauer spectra of FeIII complexes 4–6 at 90 K show very broad absorption peaks, and spectra were recollected at lower temperature (Figure 2).11 At 4 K, the FeIII complexes displayed isomer shifts (mm/s) of 0.12 for 4, 0.32 for 5, and 0.33 for 6. These isomer shifts are lower than those measured for 5- and 6-coordinate iron–porphyrin systems but fall in line with reported isomer shifts for tetrahedral high-spin FeIII ions.12 The lower isomer shift for 4 can be explained by the pronounced electron deficiency of the iron center in a weaker ligand field environment compared to that of 5 and 6. The Mössbauer spectrum for 4 shows an asymmetric singlet (|ΔEQ| = 0.21 mm/s) as would be predicted for a high-spin FeIII compound with a very small electric field gradient at the iron center. Substituting chloride for tert-butoxide increases the electric field gradient in these iron–dipyrrin complexes, which results in an increase in quadrupole splitting (|ΔEQ| = 1.31 mm/s for 5 and |ΔEQ| = 1.53 mm/s for 6).

Figure 2.

Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer spectra of 4–6 collected at 4 K.

3.4. X-Band EPR Spectroscopy on 4–6

X-band EPR spectra of complexes 4–6 were recorded at 77 K in a toluene glass (Figure 3a) and exhibit features at geff = 8.40, 5.45, and 2.95 (complex 4); geff = 6.77, 5.87, 5.12, and 1.96 (complex 5); and geff = 7.48, 5.73, 4.25, and 1.81 (complex 6). All spectra can be simulated as S = 5/2 spin systems with an isotropic g-value of 2. The complexes show small to intermediate amounts of rhombicity, with values of |E/D| of 0.13 for 4, 0.04 for 5, and 0.07 for 6. In all cases, the feature between geff = 5.5–6 originates from the ms = ±3/2 Kramers doublet, and all other features are ms = ±1/2 state transitions. No transitions originating from the ms = ±5/2 Kramers doublet are observed.

Figure 3.

(a) EPR spectra of complexes 4–6 (X-band, 9.3298 GHz) in a toluene glass at 77 K. (b) Variable-temperature magnetic susceptibility data collected for 4 under an applied dc field of 1000 Oe. (c) Low-temperature magnetization data for 4 collected between 1.8 and 10 K under various applied dc fields. Solid lines correspond to the best fits obtained with PHI.13

3.5. Magnetic Measurements on 4–6

Magnetic susceptibility data were acquired for complexes 2–6 by variable-temperature (2–300 K) magnetometry and confirmed high-spin ground states for complexes 4–6. The data show similar temperature dependencies of the magnetic susceptibility for FeIII complexes (Figure 3b for 4, Figures S-14, S-16, and S-17 for 2, 5, and 6, respectively). DC magnetic susceptibility measurements at 295 K give χMT (cm3K/mol) values for compounds 4 (4.07), 5 (3.96), and 6 (3.93) close to the spin-only value for an S = 5/2 spin ground state (4.38 cm3K/mol). Notably, the susceptibility data for 2 display a downturn at a temperature higher than that of the data for 4–6, suggestive of the presence of significant zero-field splitting (ZFS) for ferrous 2 and decreased ZFS for ferric 4–6. Further support for the ZFS is obtained from low-temperature magnetization data at various applied dc fields. The reduced magnetization plots reveal a series of nonsuperimposable isofield curves (Figure 3c for 4, Figures S-14, S-16, and S-17 for 2, 5, and 6, respectively). Fits to the data obtained using PHI13 give axial and transverse zero-field splitting parameters D and |E| (listed in Table 2): 4 (D = 1.82 cm−1), 5 (D = 1.28 cm−1), and 6 (D = 0.99 cm−1) compared to that of 2 (D = −12.43 cm−1).

3.6. Redox Behavior of Compounds 4–6

The electrochemical properties of complexes 4–6 were investigated by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV, Figures S-11, S-12, and S-13) to determine the influence of the ancillary ligands on the electronic structure of the FeIII complexes (Figure 4). All three compounds present a reversible oxidation event at E1/2 (V): 0.81 (4), 0.68 (5), and 0.61 (6) that is consistent with ligand-centered oxidation, though a FeIV/FeIII couple cannot be ruled out. Complex 4 also shows a reversible reduction at E1/2 = −0.44 V, which corresponds to a FeIII/FeII couple. In contrast, 5 and 6 present quasi-reversible reduction events at E1/2 = −1.04 and −1.63 V, respectively. Therefore, the average cathodic shift per chloride substitution for tert-butoxide is 0.6 V. The potentials obtained from the CV highlight the pronounced influence of the coordinated ancillary ligands onto metal-centered redox events. tert-Butoxide ligands stabilize the higher FeIII oxidation state and cathodically shift the attendant reduction potentials observed.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammograms of complexes 4–6 at room temperature in dichloromethane using 0.1 M nBu4NPF6 as supporting electrolyte. Working electrode: glassy carbon. Reference electrode: Ag/AgNO3. Counter electrode: Pt wire. Scan rate: 0.1 V/s.

3.7. Absorption Spectroscopy on 4–6

The UV/vis spectra (Figure 5a, Table 2) for the characteristically intense red-pink FeII complexes 1, 2, and 3 feature bands with maxima at 556 nm for 1, 530 nm for 2, and 531 nm for 3, respectively. The bands are of similar intensity (ε = 64.4 × 103 M−1 cm−1 for 1, ε = 71.6 × 103 M−1 cm−1 for 2, and ε = 67.8 × 103 M−1 cm−1 for 3) and are assigned as dipyrrin ligand-to-ligand charge transfer bands (LLCT) akin to the Soret bands in porphyrin chromophores.14 Oxidation of dichloride 2 resulted in the immediate color change from red-pink to dark green (ε = 19.7 × 103 M−1 cm−1; Figure 5a), while the oxidized 5 and 6 retain a pink color but display shifted absorption maxima (Figure 5a) and lower extinction coefficients [ε (M−1 cm−1): 30.8 × 103 (5), 53.4 × 103 (6)]. To exclude possible ligand modiffcation during the oxidation of 2 to 4, which could result in the pronounced decrease in intensity of the LLCT and the observation of additional transitions, 4 was reduced by one electron using cobaltocene to give [Cp2Co][(ArL)FeIICl2], and complete restoration of the π–π* transition was observed (Figure 5b). Consequently, permanent ligand modiffcation can be excluded, and the low intensity bands can be described as characteristic of 4.

Figure 5.

(a) UV/vis spectra for complexes 1–6. Spectra obtained at room temperature in benzene; average ε values calculated from a minimum of four concentrations. (b) Spectral change during reduction of 4 (blue) with cobaltocene to give [Cp2Co][(ArL)FeCl2] (black). (c) Spectral changes during reduction of 5 (red) to 1 (black).

3.8. Reactivity with Cyclohexadiene

To assess the influence of the ancillary ligands on the reactivity of the FeIII complexes, we investigated their activity in hydrogen atom abstraction reactions. When complex 5 was heated to 70 °C in the presence of cyclohexadiene or dihydroanthracene, complete consumption of starting material was observed. 1H NMR spectroscopy as well as UV/vis spectroscopy confirmed formation of 1 (Figure 5c). No reaction occurred upon prolonged heating in benzene in the absence of cyclohexadiene, and the observed reactivity could therefore either be explained by ejection of tert-butoxyl radical or by a direct hydrogen atom abstraction (HAA) mechanism. If the first pathway were operative, HAA from toluene should be feasible (BDE (kcal/mol): PhCH3 = 90; tBuO–H = 105),15 but substantial decay of 5 in toluene over a time-course of 24 h at 120 °C was not observed. We therefore propose a direct HAA pathway to be operative. The observed reactivity resembles the generally accepted enzymatic mechanism of lipoxygenases in which a mononuclear nonheme FeIII–OH abstracts a hydrogen atom to form a FeII–H2O species. 16 Hydrogen atom abstraction reactivity from ferric species has furthermore been demonstrated using ferric alkoxide and hydroxide model complexes.17 Heating of 6 under identical conditions did not result in decay of the FeIII species, and a temperature of 85 °C was necessary to induce HAA from cyclohexadiene. In contrast, if 4 was heated in cyclohexadiene to 70 °C, formation of 1 did not occur, and instead, a blue decomposition product formed, which is indicative of dipyrromethene ligand oxidation.

3.9.1. Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations: Ground State Electronic Structure

The electronic structure of the complexes (using the crystallographic positions of all atoms) was examined using the ORCA suite of programs.18 Single point energies were calculated using the B3LYP19 functional with TZVP as basis set on Fe, N, Cl, and O and the SVP basis set on all other atoms.20 This combination of functional and basis set was chosen because we had previously established that it accurately predicts measured Mössbauer parameters of iron–dipyrrin complexes.2a,b The Mössbauer parameters for all new compounds were calculated to correlate theory with experimental data and matched remarkably well.

The spectroscopically validated computational model indicates that the effective amount of spin at the iron center stays constant for all FeII complexes (1–3) with a calculated Mulliken spin density (MSD) on iron of 3.7 (Table 3). Upon oxidation, the MSD at iron increases as would be expected for removal of a β electron from the d-orbital manifold. However, the total MSD on iron is calculated to be 4.1 for 4–6 instead of the expected five unpaired electrons. The dipyrrin ligand MSD is calculated to be 0.34 for 4, 0.27 for 5, and 0.19 for 6, indicating a diminished contribution to the overall spin composition as the more electron-rich alkoxide ligands are substituted in. Indeed, the mixed Cl/OtBu 5 is calculated to exhibit a greater MSD on the alkoxide O (0.38) compared to that of Cl (0.23) (Table 3; illustrated in Figure 6).

Table 3.

Calculated Mulliken Spin Densities for Complexes 1–6

| iron | dipyrrin | chloride | tert-butoxide | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.72 | 0.14 | 0.13 | |

| 2 | 3.71 | 0.08 | 0.10, 0.10 | |

| 3 | 3.68 | 0.07 | 0.09, 0.12 | |

| 4 | 4.08 | 0.34 | 0.29, 0.28 | |

| 5 | 4.07 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.38 |

| 6 | 4.08 | 0.19 | 0.33, 0.33 |

Figure 6.

Mulliken spin density plot calculated for 5 (isovalue 0.01).

3.9.2. Excited State Electronic Structure Calculations

The oxidation of dichloride 2 to 4 is accompanied by a significant color change from red-pink 2 to a deep green in 4, while both 5 and 6 largely retain the color of their ferrous precursors. To interrogate this phenomenon and the nature of the excited states in general of the FeIII species, we performed time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations at the same level of theory. Single-point excited state energy calculations were used to determine the 30 lowest-energy states. The deviation between calculated and experimental optical transitions is comparable to that seen in other systems (Figures S-33, S-35, and S-42).21 All calculated transitions have multiconfigurational character, and predicted bands can be interpreted using difference densities between ground-state and excited-state orbitals. Although the exact energies of the calculated transitions do not align precisely with experiment, the predicted absorption spectra qualitatively reffect experimental observations (Figure 5a). TD-DFT analysis predicts one intense electronic transition for FeII complexes 1–3, in agreement with the single, strong absorption observed experimentally. For example, the intense band calculated for 2 at 438 nm (fosc = 0.784) has its largest contribution from dipyrrin-based π–π* (LLCT) transitions with very little metal contribution (Figures 7a and S-38) with similar observations made for 1 (Figure S-36).

Figure 7.

Electron difference density map for key predicted transition for 2 (a), 4 (b), and 6 (c). Electrons move from yellow to red areas upon excitation (isovalue 0.0025).

The predicted transitions for the symmetric ferric complexes 4 and 6 have smaller oscillator strengths than those for their ferrous precursors, which is in agreement with experimental data. The electronic absorption spectra for 4 and 6 (Figures S-33b and c) can be correlated to the calculated transitions for those complexes. One major intense band is predicted for 6 at 413 nm (fosc = 0.384), identified as mostly a LLCT band with some metal character mixed in (Figure 7c). The intense dipyrrin π–π* transition present in 1 and 2 is not predicted for 4, which is consistent with the substantial color change observed. The calculation predicts a new, low-energy transition at 645 nm (fosc = 0.028), also observed experimentally. This new, low energy transition results in the very distinct green color of 4 as opposed to the orange to pink color of all other complexes. The difference density plot shown in Figure 7b identifies the major contributor to the new band as a transition featuring significant ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT). The difference density maps for 2, 4, and 6 reveal a trend toward lower oscillator strengths with increasing metal character in the acceptor orbital, an observation that can be explained invoking configuration interaction between different transitions.14,22

4.0. DISCUSSION

The key questions we sought to address in this study are the effects of ancillary ligand substitution on structural parameters, electronic structure, and redox and spectral properties in a series of iron dipyrrinato complexes. Oxidation of the ferrous precursor 1 was achieved in one of two methods: (a) anation followed by outer-sphere oxidation in the conversion of 2 → 4 and 3 → 6, or (b) inner sphere oxidation of 1 with di-tert-butyl peroxide to give the mixed ancillary ligand complex 5. Structurally, the four coordinate complexes (ferrous 2–3 and ferric 4–6) feature the same metrical trends observed previously with iron dipyrrinato complexes.2a The complexes retain the same coordination environment throughout the series, and the structural features of the ferric complexes are consistent with metal-centered oxidations without indication of extensive dipyrrin or ancillary ligand redox being evident.2a,b

To assess the effect of ancillary ligand substitution on the resultant electronic structure, the series of oxidized complexes 4–6 were examined by EPR, magnetometry, 57Fe Mössbauer, cyclic voltammetry, and absorption spectroscopy. The EPR and magnetometry data suggest that 4–6 are indeed high-spin (S = 5/2). The variable-temperature magnetic susceptibility measurements display well-isolated spin-ground states throughout the temperature range examined (20–300 K). Minor electronic differences between 4–6 are manifest in zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy. The isomer shifts observed for 4–6 fall within the typical range expected for high-spin FeIII compounds,12 and the similarity in isomer shift for 5 and 6 indicates that the electronic environment at the iron center is similar. The isomer shift for 4 is lower, which could be explained by the less π-donating character of chloride ligands compared to that of tert-butoxide. Comparison of the quadrupole splittings of 4–6 depicts a pronounced lattice contribution for 5 and 6 which is not apparent for 4.23 The chemically dissimilar ligands in 5 and asymmetric orientation of the two alkoxides in 6 lead to an inhomogeneous electric field gradient, giving rise to the nonzero quadrupole splittings observed. The qualitative trend in quadrupole splitting values is also captured by the calculated electric field gradients, lending credibility to the theoretical model employed.

We previously reported the FeIII/II couples for a series of related iron–dipyrromethene complexes and found that electronic variations on the monoanionic dipyrrinato ligand scaffold (halogenation of the pyrrolic β-positions, fluorinated aryl meso substituent) can shift the redox potential up to 350 mV.10 The present work illustrates a far more dramatic effect on the observed electrochemical properties upon examination of 4–6. Substitution of the chloride ancillary ligands in 4 with the more electron-rich tert-butoxide ligands shows an increased stabilization of the FeIII oxidation state by cyclic voltammetry, where each alkoxide substitution cathodically shifts the FeIII/II couple by 600 mV. A far more modest effect is observed in the subsequent oxidative event where a separation of less than 200 mV is observed, but the oxidation is similar to those invoked for dipyrrin oxidation events24 and would, consequently, bear less influence from the ancillary ligands. Similar analyses on ferric porphyrin complexes bearing alkoxide and chloride do show an anodic shifting for the primary oxidation event (~120 mV), though the locus of oxidation remains (iron- versus porphyrin-centered) unresolved.25–27

The absorption spectra for complexes 4–6 display significant differences. Most notably, complex 2 undergoes a substantial color change upon oxidation to 4, whereas 5 and 6 largely retain their ferrous precursor colors. The absorption spectra show a broad distribution in intensity of the absorption maxima, where the experimentally measured extinction coefficients correlate remarkably well with the calculated oscillator strengths. Not unexpectedly, the TD-DFT calculations performed suggest that highest intensity absorption bands observed in 1–3 and 5–6 are largely dipyrrin-based LLCT bands akin to Soret bands observed in metal–porphyrin complexes.14 Furthermore, the results indicate that the decreasing intensity can be ascribed to increasing metal character in the acceptor orbitals invoking LMCT contributions to the excited states, which is substantial in 4. Examples of metal–porphyrin complexes exhibiting similar Soret band broadening have been observed when the porphyrin π-system is itself being oxidized (e.g., Horseradish peroxidase), thus affecting the ground state,14,28,29 or when LMCT bands mix into the excited state LLCT, as is the case with d-type hyperporphyrins.30

Comparing the calculated electronic structures of 4–6 reveals a systematic destabilization of the β-manifold with increasing alkoxide substitution (Figure 8). While the dipyrrin π and π* orbitals remain fairly constant across the series, the Fe-based orbitals are destabilized increasingly with each successive alkoxide substitution. The contributions to the iron–alkoxide orbital destabilization arise from the alkoxide being better matched in both σ and π capacities in terms of energy match to the iron 3d orbitals. Thus, the dichloride complex 4 displays the minimal β-manifold destabilization, effectively making the dipyrrin π* and Fe 3d β isoenergetic. As a result, the potential for LMCT excitations becomes competitive with the LLCT excitations that dominate the ferrous complexes and ferric 5 and 6.31 Indeed, for complex 4, the LMCT transitions can be mixed by configuration interaction with the dominant dipyrrin LLCT, which results in the observed split low-intensity bands.32 A similar observation has been made for tetraphenylporphyrinatoiron-(III) methoxide and chloride complexes.33,34 The effect is enhanced for the dipyrrin complexes with respect to the porphyrin species as a result of the lower symmetry of the former. The cumulative effect is that, while complexes 4 and 6 are nominally electronically equivalent in the ground state, the more covalent iron–alkoxide 6 features a destabilized iron 3d β manifold (as a consequence of the higher covalency of Fe(OtBu) vs FeCl), resulting in blue-shifted potential LMCT pathways in the excited state, leaving the dipyrrin LLCT band largely unaffected.

Figure 8.

MO diagram [α (red triangle) and β (blue triangle) spin manifolds] for 4–6, including dipyrrin-based HOMO and LUMO, and singly occupied d-orbitals.

As a result of the alkoxide substitution progression from 4 → 6, the alkoxides were shown to stabilize the ferric state and enhance the iron-ancillary covalency. The latter effect is evident in comparing the calculated MSDs for 4 → 6, where the accumulated spin density on the tert-butoxide is maximized on the mixed ancillary 5 (Table 3). The proposed accumulation of spin density for 5 is manifest chemically by the propensity of 5 to abstract a hydrogen atom from cyclohexadiene. The concentration of spin density is subtly manifest in that the mixed ancillary 5 undergoes H-atom abstraction reactivity under conditions milder than those for the bis-alkoxide 6, whereas the dichloride 4 was not observed to undergo H-atom abstraction in a similar way. Given the growing interest in facilitating bond activation and subsequent bond-functionalization processes, careful attention must be paid to how metal–ligand electronic properties can be tuned to elicit the desired functional profile.

5.0. CONCLUSION

We synthesized a series of FeIII dipyrromethene complexes and showed that the ancillary ligand substitution affects both spectral and reactivity properties of the ferric complexes examined. In many cases, ancillary ligands such as chloride or alkoxides are thought of as spectator ligands that will not greatly influence the characteristics of the complex. However, we observe a substantial influence for high-spin species in weak-field environments. The electron-richness of the ancillary can dramatically impact the molecular redox properties, and the degree of metal–ligand covalency can in turn alter both ground state properties (redox potentials, electronic structure, frontier orbital composition) as well as excited state phenomena (blue-shifting LMCT). Beyond the excited state spectral property changes, the reactivity profiles of the different ferric complexes display the propensity to perform H-atom abstraction as a function of the residual spin density the ancillary ligand bears.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (GM-115815), the Dreyfus Foundation (in the form of a Teacher-Scholar Award), and from Harvard University. C.K. was supported by the Jacques-Emile Dubois Graduate Student Dissertation Fellowship Fund. We thank Dr. Yu-Sheng Chen at ChemMatCARS, Advanced Photon Source, for his assistance with single-crystal data. ChemMatCARS Sector 15 is principally supported by the Divisions of Chemistry (CHE) and Materials Research (DMR), National Science Foundation, under Grant NSF/CHE-1346572. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.inorg-chem.7b00525.

General procedures and methods, experimental procedures and spectral data for 2–6, 57Fe Mössbauer spectra, differential pulse voltammograms for 4–6, magneto-metry data, EPR spectra, solid state molecular structures and crystallographic data for 2 and 4–6, and a description of computational methods, calculated molecular orbitals, calculated electronic absorption spectra, and predicted transitions for 2–6 (PDF) Crystallographic information for 2 and 4–6 (CIF)

References

- 1.(a) Bauer I, Knölker HJ. Iron Catalysis in Organic Synthesis. Chem Rev. 2015;115:3170–3387. doi: 10.1021/cr500425u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gephart RT, Warren TH. Copper-Catalyzed sp3 C–H Amination. Organometallics. 2012;31:7728–7752. [Google Scholar]; (c) Miao J, Ge H. Recent Advances in First-Row-Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Coupling of C(sp3)–H Bonds. Eur J Org Chem. 2015;2015:7859–7868. [Google Scholar]; (d) Gao K, Yoshikai N. Low-Valent Cobalt Catalysis: New Opportunities for C–H Functionalization. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:1208–1219. doi: 10.1021/ar400270x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Su B, Cao ZC, Shi ZJ. Exploration of Earth-Abundant Transition Metals (Fe, Co, and Ni) as Catalysts in Unreactive Chemical Bond Activations. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:886–896. doi: 10.1021/ar500345f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) King ER, Hennessy ET, Betley TA. Catalytic C–H Bond Amination from High-Spin Iron Imido Complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4917–4923. doi: 10.1021/ja110066j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Iovan DA, Betley TA. Characterization of Iron-Imido Species Relevant for N-Group Transfer Chemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:1983–1993. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chirik PJ. Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation in a Weak Ligand Field: Leveraging Open Shell First Row Transition Metal Catalysts. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2017 doi: 10.1002/anie.201611959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fufirstner A. Iron Catalysis in Organic Synthesis: A Critical Assessment of What It Takes To Make This Base Metal a Multitasking Champion. ACS Cent Sci. 2016;2:778–789. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Léonard NG, Bezdek MJ, Chirik PJ. Cobalt-Catalyzed C(sp2)–H Borylation with an Air-Stable, Readily Prepared Terpyridine Cobalt(II) Bis(acetate) Precatalyst. Organometallics. 2017;36:142–150. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Kazaryan A, Baerends EJ. Ligand Field Effects and the High Spin–High Reactivity Correlation in the H Abstraction by Non-Heme Iron(IV)–Oxo Complexes: A DFT Frontier Orbital Perspective. ACS Catal. 2015;5:1475–1488. [Google Scholar]; (b) Eames EV, Harris TD, Betley TA. Modulation of magnetic behavior via ligand-field effects in the trigonal clusters (PhL)Fe3L*3 (L* = thf, py, PMe2Ph) Chem Sci. 2012;3:407–415. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sahoo D, Quesne MG, de Visser SP, Rath SP. Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions Trigger a Spin-Flip in Iron(III) Porphyrin Complexes. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:4796–4800. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crabtree RH. The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals. 5. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Sazama GT, Betley TA. Ligand-Centered Redox Activity: Redox Properties of 3d Transition Metal Ions Ligated by the Weak-Field Tris(pyrrolyl)ethane Trianion. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:2512–2524. doi: 10.1021/ic100028y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cheng R-J, Chen P-Y, Lovell T, Liu T, Noodleman L, Case DA. Symmetry and Bonding in Metalloporphyrins. A Modern Implementation for the Bonding Analyses of Five- and Six-Coordinate High-Spin Iron(III)–Porphyrin Complexes through Density Functional Calculation and NMR Spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6774–6783. doi: 10.1021/ja021344n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Suarez AIO, Lyaskovskyy V, Reek JNH, van der Vlugt JI, de Bruin B. Complexes with Nitrogen-Centered Radical Ligands: Classification, Spectroscopic Features, Reactivity, and Catalytic Applications. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:12510–12529. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Badiei YM, Dinescu A, Dai X, Palomino RM, Heinemann FW, Cundari TR, Warren TH. Copper–Nitrene Complexes in Catalytic C–H Amination. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:9961–9964. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King ER, Betley TA. C–H Bond Amination from a Ferrous Dipyrromethene Complex. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:2361–2363. doi: 10.1021/ic900219b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleinlein C, Betley TA. Unpublished results: K[(ArL) Fe(OtBu)2] (3): P21/c: a (Å) = 22.123(3), b (Å) = 32.131(4), c (Å) = 25.488(2), β (deg) = 121.783(8), V (Å3) = 15401(3) Harvard University; Cambridge, MA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang L, Powell DR, Houser RP. Structural variation in copper(I) complexes with pyridylmethylamide ligands: structural analysis with a new four-coordinate geometry index, τ4. Dalton T. 2007:955–964. doi: 10.1039/b617136b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cullen D, Desai L, Shelnutt J, Zimmer M. Conformational Analysis of the Nonplanar Deformations of Cobalt Porphyrin Complexes in the Cambridge Structural Database. Struct Chem. 2001;12:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scharf AB, Betley TA. Electronic Perturbations of Iron Dipyrrinato Complexes via Ligand. β-Halogenation and meso-Fluoroarylation. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:6837–6845. doi: 10.1021/ic2009539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blume M. Temperature-Dependent Spin-Spin Relaxation Times: Application to the Mössbauer Spectra of Ferric Hemin. Phys Rev Lett. 1967;18:305–308. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Scheidt WR, Cohen IA, Kastner ME. A structural model for heme in high-spin ferric hemoproteins. Iron atom centering, porphinato core expansion, and molecular stereochemistry of high-spin diaquo(meso-tetraphenylporphinato)iron(III) perchlorate. Biochemistry. 1979;18:3546–3552. doi: 10.1021/bi00583a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Edwards PR, Johnson CE. Mössbauer Hyperfine Interactions in Tetrahedral Fe(III) Ions. J Chem Phys. 1968;49:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chilton NF, Anderson RP, Turner LD, Soncini A, Murray KS. PHI: A powerful new program for the analysis of anisotropic monomeric and exchange-coupled polynuclear d- and f-block complexes. J Comput Chem. 2013;34:1164–1175. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gouterman M. Optical Spectra and Electronic Structure of Porphyrins and Related Rings. In: Dolphin D, editor. The Porphyrins. Vol. 3. Academic Press; New York: 1978. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo Y-R. Handbook of bonds dissociation energies in organic compounds. CRC Press LLC; Boca Raton: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson MJ, Seitz SP. In: Active Oxygen in Biochemistry. Valentine JS, Foote C, Greenberg A, Liebman JF, editors. Vol. 3 Blackie Academic & Professional; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsmith CR, Stack TDP. Hydrogen Atom Abstraction by a Mononuclear Ferric Hydroxide Complex: Insights into the Reactivity of Lipoxygenase. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:6048–6055. doi: 10.1021/ic060621e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Neese F. The ORCA program system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci. 2012;2:73–78. [Google Scholar]; (b) Neese F. ORCA—an ab Initio, Density Functional and Semiempirical Program Package, version 2.9. Universität Bonn; Bonn, Germany: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee CT, Yang WT, Parr RG. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B: Condens Matter Mater Phys. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Schäfer A, Horn H, Ahlrichs R. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian basis sets for atoms Li to Kr. J Chem Phys. 1992;97:2571–2577. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schäfer A, Huber C, Ahlrichs R. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian basis sets of triple zeta valence quality for atoms Li to Kr. J Chem Phys. 1994;100:5829–5835. [Google Scholar]; (c) Weigend F, Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2005;7:3297–3305. doi: 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dugan TR, Bill E, MacLeod KC, Christian GJ, Cowley RE, Brennessel WW, Ye S, Neese F, Holland PL. Reversible C–C Bond Formation between Redox-Active Pyridine Ligands in Iron Complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:20352–20364. doi: 10.1021/ja305679m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong Y-P, Lin Y-W. Synthesis, X-ray crystal structure, DFT-and TDDFT-based spectroscopic property investigations on a mixed-ligand chromium(III) complex, bis[2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-benzimidazolato]-(1,10-phenanthroline)chromium(III) isophthalate. Inorg Chim Acta. 2009;362:2167–2171. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gütlich P, Bill E, Trautwein AX. Mössbauer Spectroscopy and Transition Metal Chemistry. Springer; Heidelberg: 2011. pp. 97–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Nepomnyashchii AB, Bard AJ. Electrochemistry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of BODIPY Dyes. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:1844–1853. doi: 10.1021/ar200278b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rosenthal J, Nepomnyashchii AB, Kozhukh J, Bard AJ, Lippard SJ. Synthesis, Photophysics, Electrochemistry, and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of a Homologous Set of BODIPY-Appended Bipyridine Derivatives. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:17993–18001. doi: 10.1021/jp204487r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felton RH. Primary Redox Reaction of Metalloporphyrins. In: Dolphin D, editor. The Porphyrins. Vol. 5. Academic Press; New York: 1978. pp. 53–115. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee WA, Calderwood TS, Bruice TC. Stabilization of higher-valent states of iron porphyrin by hydroxide and methoxide ligands: electrochemical generation of iron(IV)-oxo porphyrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4301–4305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Felton RH, Owen GS, Dolphin D, Fajer J. Iron(IV) porphyrins. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:6332–6334. doi: 10.1021/ja00752a091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Phillippi MA, Goff HM. Electrochemical synthesis and characterization of the single-electron oxidation products of ferric porphyrins. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6026–6034. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Goh YM, Nam W. Significant Electronic Effect of Porphyrin Ligand on the Reactivities of High-Valent Iron(IV) Oxo Porphyrin Cation Radical Complexes. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:914–920. doi: 10.1021/ic980989e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wolter T, Meyer-Klaucke W, Müther M, Mandon D, Winkler H, Trautwein AX, Weiss R. Generation of oxoiron(IV) tetramesitylporphyrin. π-cation radical complexes by m-CPBA oxidation of ferric tetramesitylporphyrin derivatives in butyronitrile at −78 °C. Evidence for the formation of six-coordinate oxoironIV tetramesitylporphyrin π-cation radical complexes FeIV=OtmpX X=Cl−, Br−, by Mössbauer and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J Inorg Biochem. 2000;78:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rittle J, Green MT. Cytochrome P450 Compound I: Capture, Characterization, and C-H Bond Activation Kinetics. Science. 2010;330:933–937. doi: 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du P, Loew GH. Theoretical study of model compound I complexes of horseradish peroxidase and catalase. Biophys J. 1995;68:69–80. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80160-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Gouterman M, Hanson LK, Khalil GE, Leenstra WR, Buchler JW. Porphyrins. XXXII. Absorptions and luminescence of Cr(III) complexes. J Chem Phys. 1975;62:2343–2353. [Google Scholar]; (b) Anding BJ, Ellern A, Woo LK. Comparative Study of Rhodium and Iridium Porphyrin Diaminocarbene and N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes. Organometallics. 2014;33:2219–2229. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egawa T, Proshlyakov DA, Miki H, Makino R, Ogura T, Kitagawa T, Ishimura Y. Effects of a thiolate axial ligand on the. π→π* electronic states of oxoferryl porphyrins: a study of the optical and resonance Raman spectra of compounds I and II of chloroperoxidase JBIC. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6:46–54. doi: 10.1007/s007750000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parson WW. Modern Optical Spectroscopy. Springer; Berlin: 2015. pp. 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobayashi H, Higuchi T, Kaizu Y, Osada H, Aoki M. Electronic Spectra of Tetraphenylporphinatoiron(III) Methoxide. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1975;48:3137–3141. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng RJ, Latos-Grazynski L, Balch AL. Preparation and characterization of some hydroxy complexes of iron(III) porphyrins. Inorg Chem. 1982;21:2412–2418. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.