Abstract

Purpose

Whole-brain high-resolution quantitative imaging is extremely encoding intensive, and its rapid and robust acquisition remains a challenge. Here we present a 3D MR fingerprinting (MRF) acquisition with a hybrid sliding-window (SW) and GRAPPA reconstruction strategy to obtain high-resolution T1, T2 and proton density (PD) maps with whole brain coverage in a clinically feasible timeframe.

Methods

3D MRF data were acquired using a highly under-sampled stack-of-spirals trajectory with a steady-state precession (FISP) sequence. For data reconstruction, kx-ky under-sampling was mitigated using SW combination along the temporal axis. Non-uniform fast Fourier transform (NUFFT) was then applied to create Cartesian k-space data that are fully-sampled in the in-plane direction, and Cartesian GRAPPA was performed to resolve kz under-sampling to create an alias-free SW dataset. T1, T2 and PD maps were then obtained using dictionary matching.

Results

Phantom study demonstrated that the proposed 3D-MRF acquisition/reconstruction method is able to produce quantitative maps that are consistent with conventional quantification techniques. Retrospectively under-sampled in vivo acquisition revealed that SW + GRAPPA substantially improves quantification accuracy over the current state-of-the-art accelerated 3D MRF. Prospectively under-sampled in vivo study showed that whole brain T1, T2 and PD maps with 1 mm3 resolution could be obtained in 7.5 min.

Conclusions

3D MRF stack-of-spirals acquisition with hybrid SW + GRAPPA reconstruction may provide a feasible approach for rapid, high-resolution quantitative whole-brain imaging.

Keywords: MR fingerprinting, Quantitative imaging, High resolution, GRAPPA

1. Introduction

Quantitative imaging facilitates quantification of the biochemical and biophysical properties of tissues such as T1, T2 and proton density (PD), which have been demonstrated to be sensitive biomarkers for detecting diseases such as multiple sclerosis, epilepsy and cancer (Barbosa et al., 1994; Eis et al., 1995; Martin et al., 2015). However, due to the prohibitively long acquisition time of conventional quantitative imaging methods (e.g., multi-TI inversion-recovery for T1 mapping and multi-TE spin echo for T2 mapping) (Deoni, 2011), these quantification methods are rarely applied in clinical environments. A number of rapid quantitative imaging methods (Deoni et al., 2005; Dregely et al., 2016) are now available, but their reproducibility needs to be improved.

MR fingerprinting (MRF) (Ma et al., 2013) is a novel acquisition and reconstruction strategy that has shown great potential to simultaneously and efficiently obtain multiple parameter maps including T1, T2 and PD. A typical MRF procedure includes the following components: (i) a highly under-sampled dataset acquired with randomized TRs and Flip Angles (FAs) that create temporal and spatial incoherence, (ii) a dictionary containing the signal evolution of relevant T1 and T2 values obtained from extended phase graphs (EPG) (Weigel, 2015) or Bloch equation simulations (Ma et al., 2013), and (iii) a dictionary matching process where parameter maps are generated by a pixel-wise template matching between the acquired data and the dictionary.

Since the reconstructed image at each time point in MRF is heavily aliased, the use of a large number of time points (tps) is still needed to achieve robust quantification. This can result in relatively long acquisition time, particularly for 3D volumetric imaging. Recent studies that utilized sliding-window (SW) reconstruction (Cao et al., 2016), and sparse and/or low-rank models (Assländer et al., 2017; Davies et al., 2014; Liao et al., 2016; Mazor et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017, 2016) can mitigate this aliasing issue, and accelerate 2D MRF acquisition by reducing the number of acquisition time points. On the other hand, applications of Simultaneous Multi-Slice (SMS) to MRF (Jiang et al., 2016; Ye et al., 2016a, 2016b) have also improved the time-efficiency of MRF by simultaneously encoding multiple slices and accelerate the data acquisition process.

A challenge that emerges as the encoding efficiency of MRF improves and the target imaging resolution increases is the limited signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for high resolution imaging with small voxels. Recent studies (Buonincontri and Sawiak, 2016; Ma et al., 2016b) demonstrated that 3D MRF acquisitions enjoy large SNR efficiency benefit over their 2D MRF counterparts, and could help achieve high SNR at high resolutions. However, high resolution imaging with whole-brain coverage can lead to lengthy scans which effects motion sensitivity of 3D MRF. Unlike 2D MRF, where data for each imaging slice are acquired sequentially each over a short time frame, 3D MRF acquires data for all imaging slices together over the whole acquisition period. This improves SNR efficiency but also increases motion sensitivity. To mitigate the lengthy scans at high resolutions, a recent 3D MRF work (Ma et al., 2016a) utilizes highly under-sampled stack-of-spirals acquisition that combines highly under-sampled variable density spiral with 3 × through-partition acceleration that uniformly under-samples the partitions in an interleaved fashion. This acquisition creates a dataset with incoherent aliasing across the temporal and all spatial dimensions, which can then be reconstructed using standard gridding and dictionary matching approach. Such accelerated acquisition has resulted in a 2.6-min scan time for 1.2 × 1.2 × 5 mm3 resolution parameter mapping with 12 cm slice coverage.

In this work, we propose an approach to further accelerate 3D stack-of-spiral MRF using a hybrid SW and 3D GRAPPA reconstruction. Here, SW and gridding are used to remove in-plane aliasing and create a Cartesian dataset that is fully sampled in-plane. This then allows a direct application of parallel imaging through Cartesian GRAPPA (Griswold et al., 2002), to resolve kz under-sampling and create an alias-free SW dataset for the dictionary matching process. We demonstrated that such approach can enable a 3-fold acceleration in the partition direction while reducing the number of required TRs for pattern matching by 3.6-fold (using 420 instead of 1500 TRs as in (Ma et al., 2016a)). Our phantom study demonstrated that the results obtained by the SW + GRAPPA approach are in a good agreement with conventional quantitative methods. The utility of the proposed method is then demonstrated in vivo by both retrospective and prospective under-sampling of stack-of-spirals 3D MRF acquisitions. This allows whole-brain parameter mapping at 1 mm isotropic resolution with a whole brain coverage (260 × 260 × 192 mm3) in 7.5 min.

2. Methods

2.1. Pulse sequence development

3D slab-selective fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP) sequence (Jiang et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2016b) and stack-of-spirals acquisition (Thedens et al., 1999) was implemented for MRF. Fig. 1(a) shows the diagram of this partition-by-partition sampled 3D FISP pulse sequence. For each partition, the sequence can be separated into 2 compartments: i) a 5 s FISP acquisition with variable TRs and FA, and ii) a 2 s wait time for signal recovery, which is also being used to efficiently acquire low-flip-angle training data for GRAPPA reconstruction. The total acquisition time for each partition is 7 s. Before acquiring 3D MRF data, a 7-s dummy scan (5-s MRF plus 2-s wait time) was employed to achieve steady-state longitudinal magnetization.

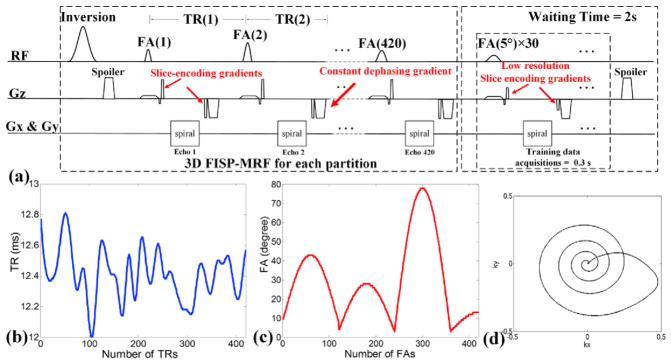

Fig. 1.

(a) Pulse sequence of 3D-MRF with partition-segmented GRAPPA training data acquisition. The TRs and FAs of 420 time points per each partition are shown in (b) and (c), respectively. (d) One interleaf of normalized variable density spiral trajectory.

For FISP-MRF acquisition in each partition, a total of 420 time-points were acquired, with the number of time-points chosen based on our previous SW 2D MRF work (Cao et al., 2016). The TRs of the acquisition varied between 12 and 13 ms with a Perlin noise pattern, and the FAs varied sinusoidally from 5° to 80°, as shown in Fig. 1(b) and (c). TE was fixed to 2.7 ms for all time-points. Variable density spiral (VDS) k-space sampling trajectory (Kim et al., 2003), which consisted of 30 interleaves with zero-moment nulling, was utilized for acquisition (Fig. 1(d)). Interleaves were rotated by 12° for each TR to create full-sampling for every 30 TRs. In each TR, a pair of encoding and rewinder gradients was utilized for slice-encoding at each partition, and a constant dephasing gradient was used to provide a constant phase shift required for the FISP acquisition.

Partition-segmented GRAPPA training data acquisitions were embedded into the sequence during the 2-s waiting periods. To fully-sample k-space for each kz partition of the training data, 30 spiral interleaves were acquired across a 0.3-s time-period at the end of each MRF partition acquisition using a constant TR of 10 ms and a FA of 5°. Since the 3D MRF acquisition is Rz-fold under-sampled, which indicates that every Rz partition is sampled along the slab dimension, the fully-sampled GRAPPA training data are acquired at Rz-fold lower partition resolution to maintain uniform full Δkz sampling. Subsequent to the GRAPPA training acquisition, a spoiler gradient was applied to eliminate the residual transverse magnetization, and the remaining 1.7 of the 2 s wait period was used for T1 recovery prior to the next MRF partition acquisition, to improve SNR.

2.2. Sliding-window reconstruction

The SW approach (Cao et al., 2016) with a window width of 30 frames was applied along the temporal dimension in each partition of the under-sampled MRF data, as shown in Fig. 2(a). The window width of 30 can fully cover the k-space so that after SW combination and the application of non-uniform fast Fourier transform (NUFFT) (Fessler, 2007), the images are fully sampled in-plane, and the remaining aliasing is only from the under-sampling along kz. Fig. 2(a) shows the aliased 3D images after SW processing. This combined data can then be Fourier transformed to 3D Cartesian k-space, to allow kz under-sampling to be resolved using conventional Cartesian parallel imaging methods.

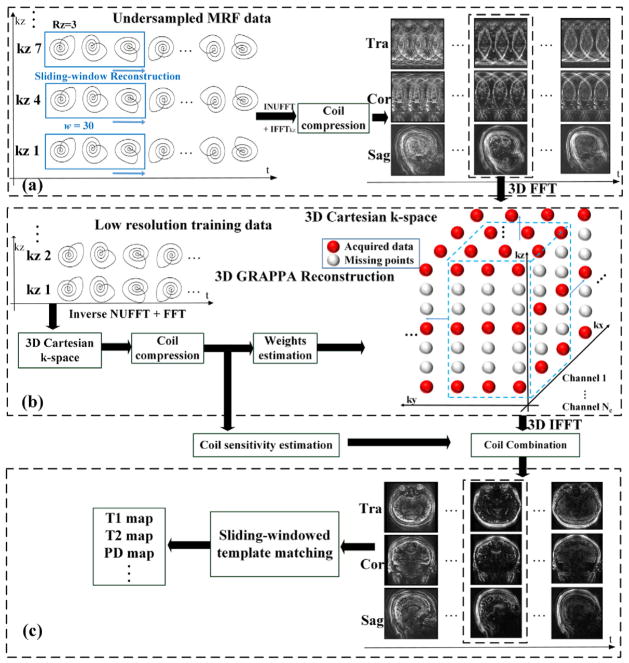

Fig. 2.

Hybrid of sliding-window and 3D GRAPPA reconstruction strategy. (a) sliding-window reconstruction was used for every partition of under-sampled MRF data, and transformed to Cartesian k-space after geometry coil compression. (b) 3D GRAPPA reconstruction. The acquired training data were utilized for coil sensitivity and 3D GRAPPA kernel estimations. Then the trained GRAPPA weights were applied on under-sampled Cartesian k-space and the sensitivity maps were used for coil combination. (c) The final T1, T2 and PD maps were obtained by sliding-windowed dictionary recognition from aliasing-free volumes.

2.3. 3D GRAPPA reconstruction

We utilized GRAPPA reconstruction (Griswold et al., 2002) to eliminate the aliasing along z. As shown in Fig. 2(b), both kx and ky are fully-sampled (red points) and the missing points (white) are along kz. To reconstruct the missing points, a 3D GRAPPA kernel was used, which has been shown to provide improved reconstruction over the conventional 2D approach (Blaimer et al., 2006). The flow chart of 3D GRAPPA reconstruction is shown in Fig. 2(b), which includes following steps:

Coil compression to accelerate GRAPPA reconstruction. Geometric-decomposition coil compression (Zhang et al., 2013) was used to compress the acquired 32-channel head coil data to 12 virtual channels to achieve (32/12)2 = 7.1 × faster reconstruction.

GRAPPA kernels estimation from the center fully-sampled k-space region of the training data. A 3D kernel size of 3 × 3 × 3 was used.

GRAPPA reconstruction for all time-points of SW combined MRF data. Here, image-domain GRAPPA (Breuer et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2005) was implemented to accelerate the reconstruction.

Coil sensitivity estimation and coil combination: 3D coil sensitivity profiles were estimated from the GRAPPA training data using ESPIRiT (Uecker et al., 2015, 2014), and were used for coil combination.

2.4. Dictionary generation and pattern recognition

The dictionary was generated by extended phase graph (EPG) method (Weigel, 2015) using variable TRs and FAs as shown in Fig. 1(b) and (c). The effect of the low-flip-angle GRAPPA training acquisitions and the T1 recovery during the waiting period between each partition were also included in the dictionary generation process. The initial longitudinal magnetization is at a fully relaxed state (Mz = 1) prior to the first 5-s MRF acquisition and 2-s recovery period, after which it will be in a partial recovery state (Mz = Mz_ss, with Mxy = 0). In subsequent periods right after the 5-s MRF plus 2-s recovery, the magnetization will also be in this same state (Mz = Mz_ss, with Mxy = 0), analogous to what would happen in a standard inversion recovery gradient-echo acquisition. Therefore, for given T1 and T2 values, we perform two EPG simulations to generate the dictionary. On the first simulation, we set the initial longitudinal magnetization to 1 and calculate the value of the partially recovered longitudinal magnetization (Mz_ss). On the second simulation, we use Mz_ss as the initial starting magnetization to generate the final dictionary. Correspondingly, in our acquisition, we employ a 7-s dummy scan (5-s MRF plus 2-s wait time) to achieve steady-state longitudinal magnetization before acquiring our MRF data.

T1 and T2 values ranged from 0 to 5000 ms and 0–4000 ms were sampled using 160 and 196 points respectively, with values finely sampled at 20 ms intervals of T1 and 2 ms intervals of T2 around the expected T1 and T2 values of white-matter and gray-matter (T1 = [20:20:3000, 3200:200:5000] ms and T2 = [10:2:140, 145:5:300, 310:12:1000, 1050:50:2000, 2100:100:4000] ms). Since the reconstructed images underwent SW processing with a window width of 30, the dictionary was temporally averaged accordingly as per (Cao et al., 2016). The SW + GRAPPA reconstructed 3D volumes were then normalized and pattern matched voxel-wise to the corresponding dictionary using the maximum inner product method (Fig. 2(c)) to obtain T1 and T2 maps. For 3D MRF, the PD was first reconstructed slice by slice without normalization and then scaled within the whole volume to be in the range [0, 1].

2.5. Phantom validation

The 3D stack-of-spirals MRF sequence was validated using an 8-tube phantom with different concentrations of agar and GdCl3 solutions. Sequence parameters were a slab acceleration factor of 3, 420 time points and 1 mm isotropic resolution. The FOV was 260 × 260 × 192 mm3 and the acquisition time was 7.5 min.

For quantitative comparison, T1 and T2 maps were obtained with the same resolution by multi-TI inversion-recovery spin echo (IR-SE) and spin echo (SE) sequences (one refocusing pulse) with different TE’s respectively. In the IR-SE based T1 mapping, TR/TE = 6000/20 ms and nine TIs = 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000, 1200, 1400, 2000 ms were used. For T2 mapping, the data were acquired with multi-TE SE sequence using the following parameters: TR = 1000 ms, and seven TEs = 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 200 ms. The imaging matrices used for both IR-SE and SE were 256 × 256. Both T1 and T2 values of the phantom were then fitted by solving the nonlinear least-square methods (Barral et al., 2010; Deoni, 2011), and the total acquisition time of conventional quantification methods was ~1.2 h.

2.6. Retrospectively under-sampled in vivo acquisition

To characterize the performance of our acquisition/reconstruction approach, fully-sampled whole-brain stack-of-spirals MRF datasets were acquired and retrospectively under-sampled. Imaging parameters for these acquisitions were chosen so that each can be performed in ~15 min to minimize the potential for motion corruption (even in a highly cooperative test subject). Retrospective under-sampling and reconstruction were performed using both the proposed approach and the interleaved partition under-sampling strategy in (Ma et al., 2016a). The quantitative maps obtained from these approaches were then compared with ones obtained from the fully-sampled case using standard gridding and dictionary matching. Root mean squared error (RMSE) was utilized to quantify the deviation between the reconstructed maps Irec and fully sampled maps Ifs, which is calculated by:

| (1) |

Firstly, 3D MRF data were acquired at 1.0 × 1.0 × 4.0 mm3 resolution and 40 transverse partitions. 20% slice-oversampling was used to avoid slab boundary issue and provide better partition profile, which is important for accurate quantitative mapping with MRF (Ma et al., 2017). With the slab-oversampling, a total of 48 partitions were encoded, with 1200 time points per partition (16 s for MRF acquisition and 2 s for waiting) and a total acquisition time of 14.4 min. With a relatively low partition resolution of 4 mm, Kaiser window with β parameter of 3 was applied along kz before coil combination to mitigate Gibbs ringing (Bernstein et al., 2004). These data were then retrospectively under-sampled in both partition axis and time points. With the SW + GRAPPA method, 420 out of the 1200 acquired time points were used along with a partition acceleration of 3. To compare the proposed SW + GRAPPA method with the current state-of-the-art approach, the interleaved partition under-sampling strategy in (Ma et al., 2016a) was implemented with the same partition acceleration factor of 3 and with two different scenarios of the number of time points used, at 1200 and 420.

Our 3D-MRF was also compared with conventional methods (IR-SE for T1 maps and SE for T2 maps) in vivo. In the IR-SE based T1 mapping, TR/TE = 6000/20 ms and nine TIs = 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000, 1200, 1400, 2000 ms were used. For T2 mapping, the data were acquired using a single-echo SE sequence with seven TEs = 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 200 ms. The matrix size was 256 × 256, slice thickness was 4 mm, and the in-plane resolution was 1.0 mm. For our 3D-MRF acquisition, the accelerated data were acquired with 1.0 × 1.0 × 4.0 mm3 resolution and 48 slices.

Secondly, 3D MRF data were acquired at a higher partition resolution of 2 mm and 1.3 × 1.3 mm2 in-plane. A total of 96 partitions with 600 time points per partition were acquired to cover the whole brain in 16 min, with FOV = 260 × 260 × 192 mm3 and sagittal slice direction (no slab over-sampling required). Here only 600 time points per partition were acquired to limit the total acquisition time and its corresponding motion issue. For SW + GRAPPA reconstruction, the first 420 out of 600 time points were utilized along with a total of 32 partition encodings at 3-fold partition acceleration. The center region of acquired training data was utilized for GRAPPA kernel estimation. The interleaved under-sampling strategy was also implemented with the same slab acceleration factor of 3 and 420 time points.

Using the second dataset, a representative g-factor map of the GRAPPA reconstruction was also calculated from the reconstruction weights (Breuer et al., 2009).

2.7. Prospectively under-sampled in vivo acquisition

To push the resolution of 3D MRF further, a protocol with prospectively under-sampled (Rz = 3) 1 mm isotropic data and whole brain coverage was used with 420 time points per partition. Acquisition was performed sagittally with a FOV of 260 × 260 × 192mm3 and a scan time of 7.5 min (The acquisition for full partition-sampled dataset at 1200 time points would have taken ~1 h). Three subjects were scanned with 1 mm isotropic resolution.

All phantom and in vivo measurements were performed on a Siemens Prisma 3T scanner with a 32-channel head coil, and all reconstruction algorithms were implemented in MATLAB R2014a (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA).

3. Results

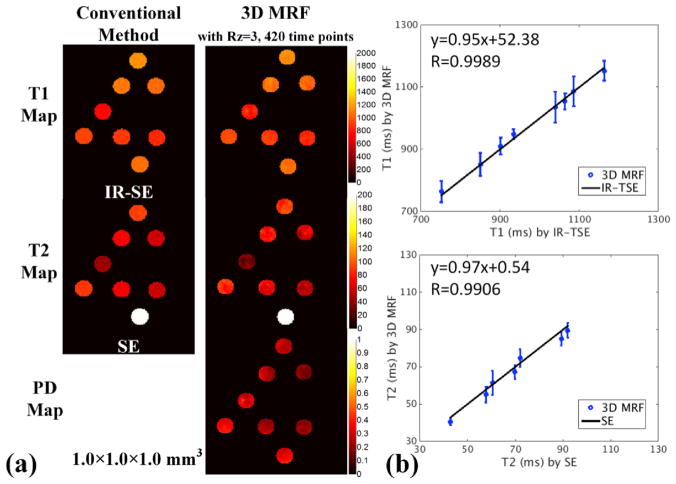

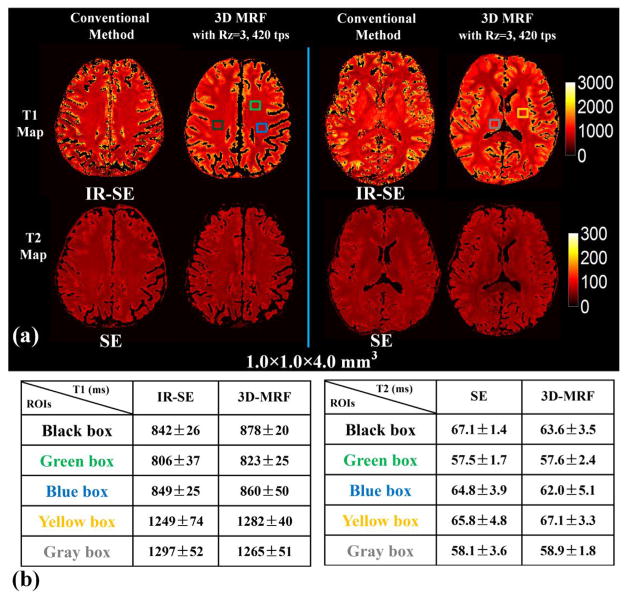

Fig. 3(a) shows high-resolution (1 mm isotropic) T1, T2 and PD maps from the phantom acquisition using conventional quantitative imaging and the proposed accelerated 3D MRF method. Fig. 3(b) shows the quantitative comparisons conducted between T1 and T2 values of phantom obtained from 3D MRF acquisition and from the conventional methods. It can be seen that T1 and T2 values obtained by the proposed 3D MRF method are consistent with the conventional quantification method with minimal bias.

Fig. 3.

(a) Phantom comparison between conventional quantitative methods and 3D MRF. (b) Quantitative evaluation of 3D MRF.

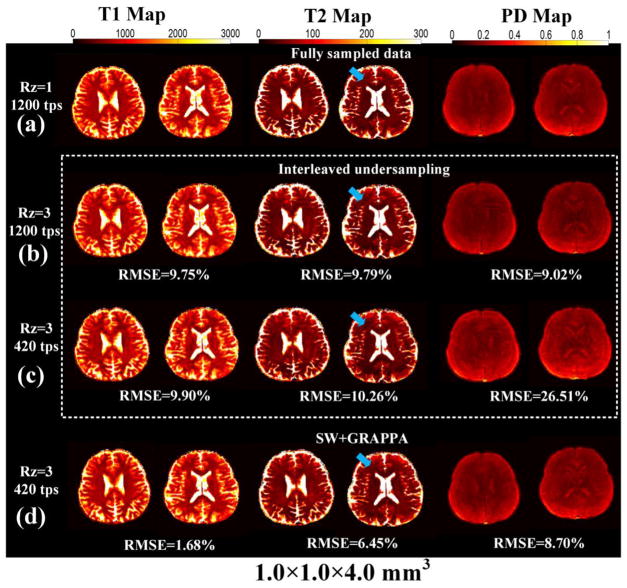

For in vivo study, Fig. 4 shows two representative slices of the reconstructed T1, T2 and PD maps from 1.0 × 1.0 × 4.0 mm3 acquisition obtained by (a) fully sampled data (Rz = 1, 1200 time points), (b) interleaved strategy with Rz = 3, 1200 time points, (c) interleaved strategy with Rz = 3, 420 time points, and (d) SW + GRAPPA with Rz = 3, 420 time points. From the calculated RMSE, when 1200 time points per partition were used in the interleaved strategy, reasonable reconstruction was achieved (Fig. 4(b)) with RMSEs less than 10%. However, when the number of time-points used in the interleaved strategy decreases to 420, significant increases in RMSE can be observed, especially for the PD maps. The blue arrows in Fig. 4 indicate that while the T2 maps obtained by the interleaved strategy contain residual aliasing, the results from the SW + GRAPPA method are consistent with fully sampled data. Furthermore, the RMSE results of T1, T2 and PD maps shown in Fig. 4 demonstrate that SW + GRAPPA method has better reconstruction performance with reduction of RMSE than interleaved strategy with Rz = 3 from both 1200 and 420 time points.

Fig. 4.

Two slices of reconstructed T1, T2 and PD maps for 1.0 × 1.0 × 4.0 mm3 data obtained by (a) fully sampled data (Rz = 1, 1200 time points), (b) interleaved strategy with Rz = 3, 1200 time points, (c) interleaved strategy with Rz = 3, 420 time points, and (d) SW + GRAPPA with Rz = 3, 420 time points. The blue arrow indicates that while T2 maps obtained by interleaved strategy contain residual aliasings, the results of SW + GRAPPA method are consistent with fully sampled data.

The in vivo comparison between 3D MRF and conventional quantitative acquisitions are shown in Fig. 5. There were minor slice mismatches between conventional methods and MRF data due to small motion during the lengthy acquisition (~1.5 h) which were hard to avoid for such in vivo study. The CSF was also masked out in our results below because of the inaccuracy in the T1 and T2 estimates obtained through conventional methods from limited TR and TE ranges used in our protocols (chosen to keep the scan time manageable). In Fig. 5(a) it can be seen that T1 and T2 values obtained by the proposed 3D MRF method are consistent with the conventional quantification methods. Fig. 5(b) reports T1 and T2 values from five representative ROIs (black, green, blue, yellow and gray boxes shown in Fig. 5(a)) obtained by conventional methods and 3D MRF, where the estimated values are shown to be in good agreement.

Fig. 5.

(a) comparison between 3D-MRF and conventional methods (IR-SE for T1 maps and SE for T2 maps) in vivo. (b) T1 and T2 values from five representative ROIs (black, green blue, yellow and gray boxes shown in figure (a)).

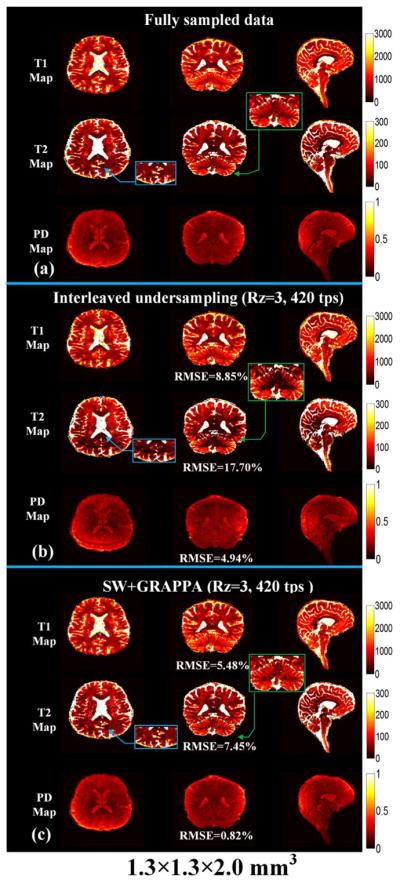

The T1, T2 and PD maps obtained from (a) fully sampled MRF data with resolution of 1.3 × 1.3 × 2.0 mm3, (b) interleaved under-sampling strategy (Rz = 3, 420 time points) and (c) the proposed SW + GRAPPA (Rz = 3, 420 time points) are displayed in Fig. 6. For T1 maps, both interleaved under-sampling and the proposed method generated results that are in a good agreement with the fully sampled data, while for T2 map, the proposed method has better consistency when compared to the interleaved under-sampling strategy. The zoomed-in views indicated by green and blue boxes in Fig. 6 illustrate that the interleaved under-sampling strategy at reduced time points of 420 can result in an underestimation of T2 values and residual aliasing. The RMSE of T1, T2 and PD maps shown in Fig. 6 also demonstrates that the proposed SW + GRAPPA reconstruction has much reduced error than the interleaved under-sampling strategy (5.48% versus 8.85% for T1 maps, 7.45% versus 17.70% for T2 maps and 0.87% versus 5.22% for PD maps).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of MRF results between (a) fully sampled data (96 partitions and 600 time points), (b) undersampled data (32 partitions and 360 time points) with interleaved strategy and (c) SW + GRAPPA reconstruction. The volume resolution is 1.3 × 1.3 × 2.0 mm3 with sagittal acquisition. The blue and green boxes are the zoomed view of T2 maps.

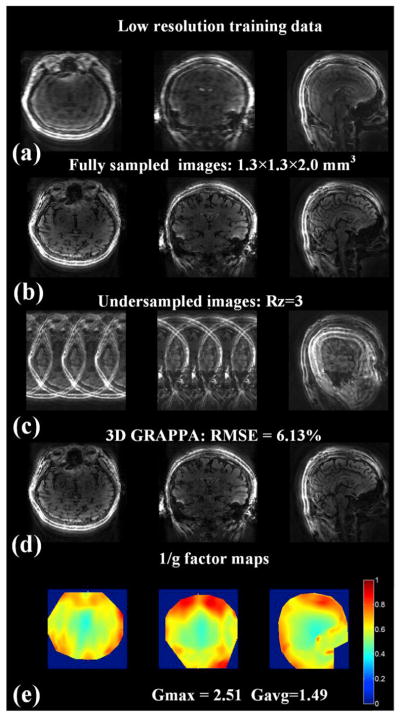

The reconstruction of SW combined data with resolution of 1.3 × 1.3 × 2.0 mm3 are displayed in Fig. 7. Fig. 7(a) and (b) show the three orthogonal views of the training data, and the fully sampled images obtained from SW operation on the 135th–164th time points. Fig. 7(c) and (d) show the corresponding images from 3-fold partition under-sampled data before and after parallel imaging reconstruction respectively. It can be seen that the 3D GRAPPA reconstruction has effectively removed the aliasing in the partition direction, with the RMSE of the reconstructed images at 6.13% when compared with the fully sampled images. Note that minor residual in-plane aliasing/ringing is present in all images (a,b,d) due to the data from the spiral interleaves not being acquired in steady-state at the same signal level. Such residual aliasing should be effectively removed by the dictionary matching process of MRF. Fig. 7(e) shows the three views of 1/g-factor maps of the proposed 3D GRAPPA reconstruction. The maximum g-factor Gmax is 2.51, and the average g-factor value Gavg is 1.49.

Fig. 7.

(a) Three orthogonal views of acquired training data with low resolution. (b) Fully sampled data from 135th to 164th time points after sliding-window combination. (c) Retrospectively under-sampled data along partition direction and (d) the corresponding results with 3D GRAPPA reconstruction. (e) 1/g factor maps in the three orthogonal orientations. The maximum and average values of g-factor were also shown in (e).

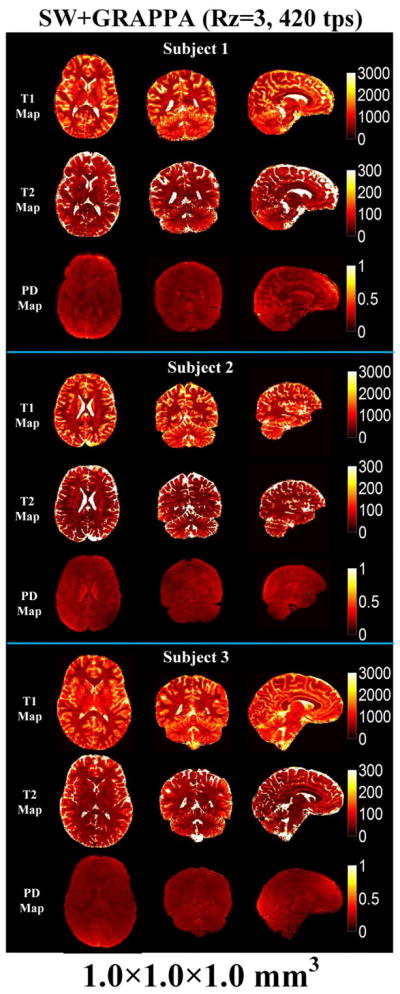

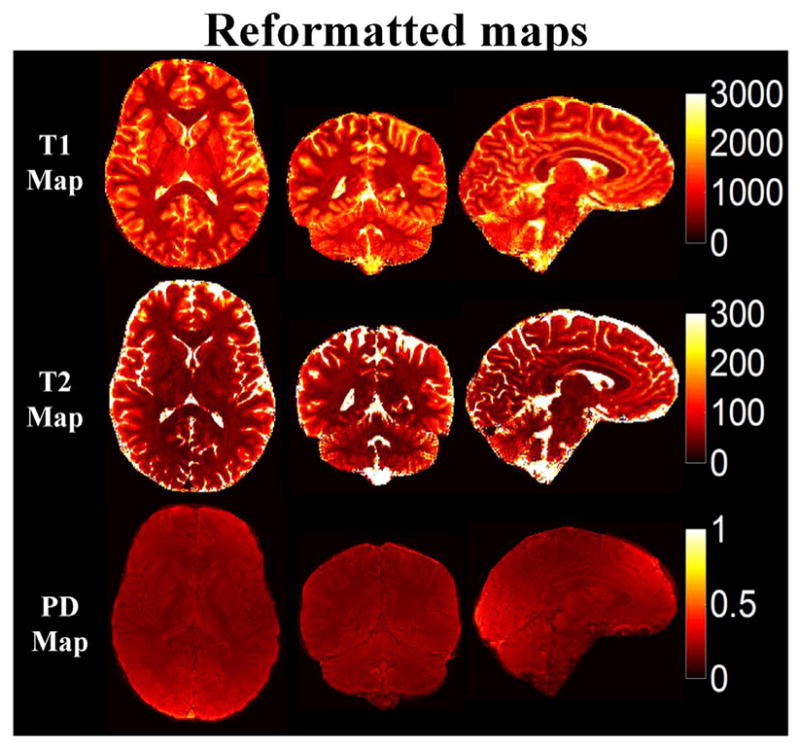

Three orthogonal views of the quantitative maps of three subjects obtained from 1 mm isotropic resolution accelerated MRF acquisition (Rz = 3, 420 time points) with SW + GRAPPA reconstruction are shown in Fig. 8. With the SW + GRAPPA approach, high quality tissue parameter maps were obtained at the high resolution with a 7.5-min acquisition. However, with such a short acquisition for high isotropic resolution quantitative imaging, SNR can be a limiting factor as indicated by the presence of some noise in the quantitative maps. Fig. 9 shows the reformatted quantitative maps of Subject 3 at 1 × 1 mm2 in-plane and 3 mm slice resolution in the same three orthogonal views. Here, the reformatting helps boost SNR and mitigates the noise corruption, allowing for the generation of high quality maps at high in-plane resolution in multiple viewing planes.

Fig. 8.

Sliding-window and GRAPPA reconstruction for 1 mm isotropic prospectively under-sampled 3D MRF data (Rz = 3, 420 time points) from 3 subjects. The reconstructed whole brain data with FOV of 260 × 260 × 192 mm3 were acquired in 7.5 min.

Fig. 9.

Reformatted T1, T2 and PD maps from 1 mm isotropic data of Subject 3 that averaged adjacent 3 slices in three dimensions respectively to obtain the SNR improved maps.

4. Discussion

In this work, accelerated stack-of-spirals 3D MRF acquisition with SW + GRAPPA reconstruction was proposed for fast high-resolution multi-parameter mapping. The temporal dimension of the acquired data was combined by SW to mitigate the in-plane aliasing and allow for a straight-forward application of Cartesian 3D GRAPPA to eliminate partition aliasing. Phantom validation results demonstrate high consistency between the proposed method and conventional quantification techniques. The results of the in vivo studies indicate that the proposed method has the potential to provide high-resolution whole brain imaging within a clinically feasible timeframe.

A major advantage of 3D over 2D acquisition is the increased SNR efficiency (Bernstein et al., 2004), which allows higher resolution imaging with more accurate quantification. The SNR benefit of our 3D MRF acquisition when compared with its 2D counterpart at same resolution can be calculated as:

| [2] |

where Nz is the number of partitions, Rz is the slice acceleration factor, g is the g-factor noise amplification, and S3D and S2D are the initial signal intensity at the beginning of each partition/slice encoding period. The factor accounts for the waiting period in the 3D acquisition, during which data are not acquired. Accordingly, Tacq denotes the data acquisition window (5 s) and Ttotal represents the entire scan duration per kz partition (Ttotal = Tacq + Twait = 5 + 2 = 7 s). This factor aims to account for the added wait time, which is not present in the 2D acquisition. For 1 mm isotropic acquisition in this work, Nz = 192, Rz = 3, g = 1.49, which is the calculated average g-factor. If we assume S2D is 1.00 since the initial longitude magnetizations of 2D acquisition is fully relaxed (assuming a long enough slice interleaving acquisition period between adjacent slices), and S3D is 0.94 after a 5-s MRF acquisition and a 2-s waiting time of the previous partition acquisition which includes the low-flip-angle training data acquisition (value calculated using EPG simulation and a representative brain tissue with T1 of 1000 ms and T2 of 60 ms). Based on these numbers, the SNR benefit of our 1 mm isotropic 3D MRF compares with 2D MRF acquisition is significant at ~4.27 fold (or equal to ~18 averages of 2D acquisition).

The proposed SW + GRAPPA reconstruction allowed both in-plane and through-plane accelerations by reducing the numbers of time points and partition-encoding steps to dramatically shorten the total acquisition time. Moreover, the acquisition of the GRAPPA training data has been efficiently incorporated at the end of each partition encoding, which does not require additional scan time. This scheme also overcomes the potential issue of motion between the training data and the under-sampled MRF data, which provides improved reconstruction robustness.

With the proposed accelerated acquisition/reconstruction approach, quantitative MRF maps at 1 mm isotropic resolution can be obtained in 7.5 min, but would also be of limited SNR due to the inherent limited noise averaging window of the acquisition. A natural avenue to help boost SNR would be to acquire data at higher field strength, such as at 7T, where the B1+ inhomogeneity issue of ultra high-field would also present both a challenge and an opportunity to MRF encoding (Buonincontri et al., 2017; Cloos et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2015).

In this work, 3D GRAPPA is utilized to achieve better reconstruction performance and reduced g-factor penalty. This however comes at the cost of increased reconstruction time, especially for high-resolution MRF data with large number of time points. For example, the reconstruction time of the 1 mm isotropic data with 32 channels and 420 time points is more than 5 days using MATLAB on a standard Linux server (CentOS with 16 Intel Xeon E5-2698 CPU @2.3 GHz). In this work geometric coil compression (Zhang et al., 2013), image-domain GRAPPA (Breuer et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2005) and MATLAB parallel computing toolbox were utilized to accelerate the reconstruction, to achieve a computation time of ~20 h. The reconstruction time can be further shortened through the use of GPU compatible platforms or direct virtual coil reconstruction (Beatty et al., 2008).

The existing accelerated 3D stack-of-spirals MRF strategy utilizes an interleaved uniform partition under-sampling to create a spatio-temporal incoherent aliasing along z (Ma et al., 2016a). In contrast to this, our proposed method employs a constant uniform under-sampling along kz to enable in-plane SW reconstruction in each partition. This allows a simple parallel imaging reconstruction to cleanly resolve the aliasing in the partition direction and reduce the number of time points needed for accurate dictionary matching. The results in Figs. 4 and 5 demonstrate that the proposed method obtained more robust and accurate results than the interleaved strategy, even when 1200 time points were used for the interleaved strategy.

The formation of Cartesian k-space after the SW application obviates the need for complex non-Cartesian parallel imaging reconstruction for partition unaliasing. Without Cartesian k-space, approaches such as direct-spiral slice-GRAPPA (Seiberlich et al., 2007; Ye et al., 2016a), which can operate on highly under-sampled non-Cartesian spiral data, would have to be used. Such an approach would require the estimation of a large number of GRAPPA kernels and hence a larger training dataset, as well as more complicated training/reconstruction process. Nonetheless, the benefit of such direct approach could be to enable reconstruction of more complex trajectories that more uniformly distributes the under-sampling in both slice and in-plane directions (Deng et al., 2016). This could in turn allow for higher accelerations to be achieved at low g-factors. Such an accelerated dataset could be created by applying SW to the accelerated interleaved partition under-sampling acquisition strategy. A future research direction will be in exploring such approach, to help achieve even faster 3D MRF.

One of the limitations of SW + GRAPPA is the trade-off between temporal sensitivity and image quality. While the combination of multiple interleaves can improve the SNR and eliminate in-plane aliasing, SW reduces temporal sensitivity by smoothing the signal curves of both acquired data and dictionary entries. Our previous study (Cao et al., 2016) demonstrated that when the number of time points is in the range of 300–500, the temporal sensitivity loss for normal brain tissues is between 3% and 5% for a window width of 30. This was found to be acceptable since the resulting reduction in the dictionary sensitivity is smaller than the gap between discrete entries of a typical dictionary. The noise and aliasing reduction after SW combination can compensate the potential impact of small loss of temporary sensitivity.

The generation and simulation of dictionary in this work was based on EPG formalism, which assumes a basic Bloch model containing a single uniform environment. Such a simplified dictionary may not reflect the complex bio-chemical environments in-vivo. Recent works have tried to utilize more complex models to estimate extra-/intra-cellular T1 and chemical exchange in MRF studies (Hamilton et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017).

In this work the FISP-MRF sequence was used for the acquisition, which was demonstrated to provide good T1 and T2 quantification in the presence of off-resonance variations (Jiang et al., 2015). However, the accuracy of the estimated T1 and T2 values from the FISP-MRF sequence may still suffer from B1 inhomogeneity. Recent study by Ma. et al. (Ma et al., 2017) proposed a two-step B1 correction for 2D MRF, which can be incorporated into our accelerated 3D-MRF. The incorporation of this technique along with its validation for 3D-MRF will be part of our future work.

5. Conclusion

We introduced a novel stack-of-spirals 3D MRF acquisition with hybrid SW + GRAPPA reconstruction. Phantom and in vivo studies demonstrated that the proposed method enables high-resolution, accurate multi-parameter mapping in a reasonable timeframe. The proposed method has a great potential to be translated into clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this paper was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01EB017337, R01EB020613, R01EB017219, P41EB015896, R24MH106096, and the Instrumentation Grants S10-RR023401, S10-RR023043, and S10-RR019307. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.08.030.

References

- Assländer J, Cloos MA, Knoll F, Sodickson DK, Hennig J, Lattanzi R. Low rank alternating direction method of multipliers reconstruction for MR fingerprinting. Magn Reson Med. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Barbosa S, Blumhardt LD, Roberts N, Lock T, Edwards RHT. Magnetic resonance relaxation time mapping in multiple sclerosis: normal appearing white matter and the “invisible” lesion load. Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;12:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(94)92350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral JK, Gudmundson E, Stikov N, Etezadi-Amoli M, Stoica P, Nishimura DG. A robust methodology for in vivo T1 mapping. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:1057–1067. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty PJ, Sun W, Brau AC. Direct virtual coil (DVC) reconstruction for data-driven parallel imaging. Proc Int Soc Mag Reson Med. 2008:16. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein MA, King KF, Zhou XJ. Handbook of MRI Pulse Sequences. Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blaimer M, Breuer FA, Mueller M, Seiberlich N, Ebel D, Heidemann RM, Griswold MA, Jakob PM. 2D-GRAPPA-operator for faster 3D parallel MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1359–1364. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer FA, Kannengiesser SAR, Blaimer M, Seiberlich N, Jakob PM, Griswold MA. General formulation for quantitative G-factor calculation in GRAPPA reconstructions. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:739–746. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonincontri G, Sawiak SJ. MR fingerprinting with simultaneous B1 estimation. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76:1127–1135. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonincontri G, Schulte RF, Cosottini M, Tosetti M. Spiral MR fingerprinting at 7T with simultaneous B1 estimation. Magn Reson Imaging. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cao X, Liao C, Wang Z, Chen Y, Ye H, He H, Zhong J. Robust sliding-window reconstruction for Accelerating the acquisition of MR fingerprinting. Magn Reson Med. 2016 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26521. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cloos MA, Knoll F, Zhao T, Block KT, Bruno M, Wiggins GC, Sodickson DK. Multiparametric imaging with heterogeneous radiofrequency fields. Nat Commun. 2016:7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M, Puy G, Vandergheynst P, Wiaux Y. A compressed sensing framework for magnetic resonance fingerprinting. SIAM J Imaging. 2014;7(4):2623–2656. [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Zahneisen B, Stenger VA. Rotated stack-of-spirals partial acquisition for rapid volumetric parallel MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76:127–135. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deoni SCL. Magnetic resonance relaxation and quantitative measurement in the brain. Magn Reson Neuroimaging Methods Protoc. 2011:65–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-992-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deoni SCL, Peters TM, Rutt BK. High-resolution T1 and T2 mapping of the brain in a clinically acceptable time with DESPOT1 and DESPOT2. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:237–241. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dregely I, Margolis DAJ, Sung K, Zhou Z, Rangwala N, Raman SS, Wu HH. Rapid quantitative T2 mapping of the prostate using three-dimensional dual echo steady state MRI at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76:1720–1729. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eis M, Els T, Hoehn-Berlage M. High resolution quantitative relaxation and diffusion MRI of three different experimental brain tumors in rat. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:835–844. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessler JA. On NUFFT-based gridding for non-Cartesian MRI. J Magn Reson. 2007;188:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Chen Y, Ma D, Jiang Y, Herrmann KA, Vincent JA, Dell KM, Drumm ML, Brady-Kalnay SM, Griswold MA, Brady-Kalnay SM, Griswold MA, Flask CA, Lu L. Preclinical MR fingerprinting (MRF) at 7 T: effective quantitative imaging for rodent disease models. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:384–394. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, Haase A. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JI, Griswold MA, Seiberlich N. MR Fingerprinting with chemical exchange (MRF-X) to quantify subvoxel T1 and extracellular volume fraction. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:W35. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-17-S1-W35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Cohen O, McMahon MT, Kim YR, Rosen MS, Farrar CT. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2017. Vol. 25. Honolulu: 2017. Quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging with magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF) p. 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Ma D, Bhat H, Ye H, Cauley SF, Wald LL, Setsompop K, Griswold MA. Use of pattern recognition for unaliasing simultaneously acquired slices in simultaneous multislice MR fingerprinting. Magn Reson Med. 2016 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jiang Y, Ma D, Seiberlich N, Gulani V, Griswold MA. MR fingerprinting using fast imaging with steady state precession (FISP) with spiral readout. Magn Reson Med. 2015;74:1621–1631. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Adalsteinsson E, Spielman DM. Simple analytic variable density spiral design. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:214–219. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C, Cao X, Ye H, Chen Y, He H, Chen S, Ding Q, Liu H, Zhong J. Acceleration of MR Fingerprinting with low rank and sparsity constraints. Proceedings of the 24th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Singapore. Singapore: 2016. p. 4227. [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Coppo S, Chen Y, McGivney DF, Jiang Y, Pahwa S, Gulani V, Griswold MA. Slice profile and B 1 corrections in 2D magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Magn Reson Med. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, Liu K, Sunshine JL, Duerk JL, Griswold MA. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Nature. 2013;495:187–192. doi: 10.1038/nature11971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Hamilton J, Jiang Y, Seiberlich N, Griswold MA. Fast 3D magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF) for whole brain coverage in less than 3 minutes. Proceedings of the 24th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Singapore. Singapore: 2016a. p. 3180. [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Pierre EY, Jiang Y, Schluchter MD, Setsompop K, Gulani V, Griswold MA. Music-based magnetic resonance fingerprinting to improve patient comfort during MRI examinations. Magn Reson Med. 2016b;75:2303–2314. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Bender B, Focke NK. Post-processing of structural MRI for individualized diagnostics. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2015;5:188–203. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.01.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor G, Weizman L, Tal A, Eldar YC. Low rank magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Eng Med. 2016:2–5. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2016.7590734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiberlich N, Breuer FA, Blaimer M, Barkauskas K, Jakob PM, Griswold MA. Non-Cartesian data reconstruction using GRAPPA operator gridding (GROG) Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1257–1265. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thedens DR, Irarrazaval P, Sachs TS, Meyer CH, Nishimura DG. Fast magnetic resonance coronary angiography with a three-dimensional stack of spirals trajectory. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:1170–1179. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2594(199906)41:6<1170::AID-MRM13>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uecker M, Lai P, Murphy MJ, Virtue P, Elad M, Pauly JM, Vasanawala SS, Lustig M. ESPIRiT - an eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel MRI: where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:990–1001. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uecker M, Ong F, Tamir JI, Bahri D, Virtue P, Cheng JY, Zhang T, Lustig M. Berkeley advanced reconstruction toolbox. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2015:2486. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.12495. [DOI]

- Wang J, Zhang B, Zhong K, Zhuo Y. Image domain based fast GRAPPA reconstruction and relative SNR degradation factor. Proceedings of the 13th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Miami. 2005. p. 2428. [Google Scholar]

- Weigel M. Extended phase graphs: dephasing, RF pulses, and echoes-pure and simple. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41:266–295. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H, Cauley SF, Gagoski B, Bilgic B, Ma D, Jiang Y, Du YP, Griswold MA, Wald LL, Setsompop K. Simultaneous multislice magnetic resonance fingerprinting (SMS-MRF ) with direct-spiral slice-GRAPPA (ds-SG ) reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2016a:0. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ye H, Ma D, Jiang Y, Cauley SF, Du Y, Wald LL, Griswold MA, Setsompop K. Accelerating magnetic resonance fingerprinting ( MRF ) using t-blipped simultaneous multislice ( SMS ) acquisition. Magn Reson Med. 2016b;2085:2078–2085. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Pauly JM, Vasanawala SS, Lustig M. Coil compression for accelerated imaging with Cartesian sampling. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:571–582. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Setsompop K, Adalsteinsson E, Gagoski B, Ye H, Ma D, Jiang Y, Ellen Grant P, Griswold MA, Wald LL. Improved magnetic resonance fingerprinting reconstruction with low-rank and subspace modeling. Magn Reson Med. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhao B, Setsompop K, Ye H, Cauley SF, Wald LL. Maximum likelihood reconstruction for magnetic resonance fingerprinting. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2016;35:1812–1823. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2016.2531640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Han P, Li D. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2017. Vol. 25. Honolulu: 2017. CEST fingerprinting: a novel approach for exchange rate quantification; p. 197. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.