Abstract

Many experimental protocols in rodents require the comparison of groups that are fed different diets. Changes in dietary electrolyte and/or fat content can influence food intake, which can potentially introduce bias or confound the results. Unpalatable diets slow growth or cause weight loss, which is exacerbated by housing the animals in individual metabolic cages or by surgery. For balance studies in mice, small changes in body weight and food intake and low urinary flow can amplify these challenges. Powder food can be administered as gel with the addition of a desired amount of water, electrolytes, drugs (if any), and a small amount of agar. We describe here how the use of gel food to vary water, Na, K, and fat content can reduce weight loss and improve reproducibility of intake, urinary excretion, and blood pressure in rodents. In addition, mild food restriction reduces the interindividual variability and intergroup differences in food intake and associated variables, thus improving the statistical power of an experiment. Finally, we also demonstrate the advantages of using gel food for weight-based drug dosing. These protocols can improve the accuracy and reproducibility of experimental data where dietary manipulations are needed and are especially advisable in rodent studies related to water balance, obesity, and blood pressure.

Keywords: body weight loss, diet-induced obesity, gel food, high-fat diet, metabolic cage, urine concentration

INTRODUCTION

In the fields of cardiovascular, renal, and endocrine physiology, experimental protocols in laboratory rodents often involve changes in dietary water, Na, K, and/or fat content. Alterations in these nutrients can change feeding behavior, confound results, and increase intra- and intergroup variability, which reduce statistical power. Feeding laboratory rodents diets with markedly altered Na, K, and fat content can cause large differences in food intake, which slows weight gain or even causes weight loss. Moreover, in studies of obesity, weight loss in the obese group is a prohibitive technical hurdle. These challenges are amplified in balance studies in mice because of their small size and food intake and low urine flow rate.

The aim of this paper is to present experimental data obtained with several protocols to improve both the precision and the reproducibility of results to overcome these technical challenges. We will describe several independent experiments in which we compare conventional and modified protocols and show the benefits obtained with these modifications. One protocol concerns changes in the level of hydration in rats. The others, in mice, combine changes in dietary electrolyte content with changes in dietary fat content. General information is provided in general methods. In results, we detail protocol modifications and present physiology data compared with conventional protocols.

GENERAL METHODS

We collected data from male Sprague-Dawley rats (Iffa Credo) used in previous studies (4, 13) and present them in in greater detail.

We used male 6-wk-old C57BL/6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) for all mouse experiments. We fed mice purified diets (Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ) containing either 10 [low fat (LF); cat. no. D12450B] or 60% fat/kcal [high fat (HF); cat. no. D12492] formulated as powder, pellet, or gel. Powder and pellet formulations were commercially available. Starting with pellets, we made all gel diets in our laboratory. The LF diet contained 3.845 kcal/g, 0.10% Na wt/wt, and 0.60% K wt/wt. The HF diet contained 5.243 kcal/g, 0.14% Na wt/wt, and 0.77% K wt/wt. The difference in electrolyte content (36% greater in the HF diet per unit weight) results in equivalent electrolyte intake per day because HF diets are more calorie rich and mice spontaneously eat less of the food to obtain the same calories as LF-fed mice. Similarly, high-Na diets contained 1.53% wt/wt and 2.06% wt/wt in LF and HF diets, respectively (180 µmol/kcal). High-K diets contained 5.00 and 6.63% K wt/wt in LF and HF diets, respectively (366 µmol/kcal).

Gel food.

We prepared gel diets by mixing the food with water and either agar-agar in rat experiments or a concentrated agarose solution in mouse experiments. Agar and agarose are nondigestible polysaccharides that are not absorbed and are excreted in the feces. We added powdered diet, salts, and half the intended water to a beaker, weighed it to later replace any evaporated water, then placed it in a 37°C water bath for ≥1 h. In a separate beaker, we added 105% of the remaining water and 105% of the total agarose (EZ Bioresearch, St. Louis, MO). We heated the solution until it was boiling and the agarose was dissolved. We stirred the solution at a fast speed to avoid uneven gelling of the solution until it reached 65°C. We then reweighed both the beaker with powdered food and the agarose solution, replaced any evaporative water losses, and combined the food solution with 100% of the intended agarose solution. We thoroughly mixed the combined solution with a spatula and rapidly poured it into the individual petri dishes.

We added or removed food to each dish to provide the intended mass of food to each animal. When dishes were used to feed a single mouse for a day, we poured gel into dishes set at an angle, as mice can pull off thin layers of food en masse, and drop it through the grate floor. We stored dishes of gel diet at −20°C for ≤1 mo and defrosted them 1 day before use.

Gel foods contained 2.0 and 2.7 ml water/g food in LF and HF diets, respectively. Added Na (Na chloride; Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) ranged from 0 to 1.5% wt/wt in LF diets (0–2.1% in HF diets). Added K (K chloride and tripotassium citrate; Fisher Scientific) content ranged from 0 to 5.0% wt/wt in LF diets (0–6.3% wt/wt in HF diets).

For gel diets with added Na or K salts,

Balance studies in mice.

We used single-mouse metabolic cages (Techniplast) with small modifications to employ gel diets and minimize water loss. To eliminate loss from water bottles, we secured the water bottle to its holder with velcro ties and inserted a 1-ml pipette tip between the flange of the water bottle holder and flange of its insertion slot (Fig. 1). We fed the mice gel food in 6-cm-diameter dishes by removing the standard food troughs and adhering the dish to the opening using rubber bands. To prevent the mice from scratching food in these dishes and dropping food through the grate cage floor, we modified 6-cm petri dish tops with a 5-cm hole in the center and placed this lid over the gel food dishes. With these modifications and in combination with calorie restriction, mice almost never displaced food out of the cages after 4 days of acclimation (unpublished observations). We refreshed gel food to the mice between 11 AM and 1 PM daily.

Fig. 1.

Modifications to metabolic cages to provide gel food and reduce loss from water bottles.

In experiments where we compared powder and gel diets in rats, we added an equivalent amount of agarose powder to the powder diet so that only the water content differed between the two diets.

Mice temporarily decrease their food intake and lose weight when first housed in metabolic cages. Therefore, to permit a return to steady state, we housed mice in cages for ≥3 days before we initiated data collection. We calculated food and water intake as change in food dish and water bottle weight.

We acclimated mice to gel diets for 3 days before transferring them to metabolic cages. During metabolic cage acclimation, we washed cages every 2 days and daily during urine collections. We rinsed collection systems in tepid water to remove any gross contamination, in dilute detergent (Nalgene L500, Rochester, NY), and with deionized water and finally air-dried them overnight before use. This requires twice the collection systems as mice in an experiment. We washed the cage housing (the base holding the collection system), the water bottle holder, and the cage walls weekly.

During urine collections, we expressed urine from the urinary bladder through gentle massage of the abdominal wall before starting and upon ending a collection period. We collected urine under water-saturated mineral oil. Metabolic cages fail to capture urine voided onto the outer edge of the cage, which settles on the outer flat edge of the urine funnel and in the bottom adapter of the funnel. These two areas can hold 0.4 ml of urine (data not shown). We collected any stagnant urine from these areas using a pipette. We weighed urine and immediately froze and stored an aliquot at −20°C for future analysis.

For rat experiments, the investigators received institutional authorization to experiment with living animals and completed these experiments before formal Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees were established. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Stanford University approved all mouse experiments, and we euthanized the mice in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Mild food restriction.

To reduce day-to-day, intragroup, and intergroup variability, we imposed a mild restriction on the daily food allowance to all animals. We first evaluated the mean daily food intake at steady state by weighing food dishes on ad libitum feeding for 2–3 days. We then limited the amount of food to 90% of the mean daily food intake observed for all animals.

Measuring evaporation in gel food in metabolic cages.

Due to the water content and high surface area of gel food dishes, analysis of food and water intake should compensate for evaporative losses. We measured the evaporative water loss of several amounts of food over 8 h. We prepared gel food with either LF or HF content and 2 ml water/g food. We filled 6 cm Petri dishes with 0.25, 0.5, or 1 g of gel food and placed these into empty metabolic cages. After 8 h, we weighed the dishes again. Linear regression of these data generated the following adjustment equations:

| For LF diets, |

and for HF diets,

Regression equations were not significantly different between diets with 1.4–2.1 ml water/g dry food. We applied these equations to all experiments using gel food.

Statistics.

For pairwise comparisons, we defined significance by two-tailed t-test (P < 0.05). For comparisons of variance, we defined significance by F-test for unequal variance (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

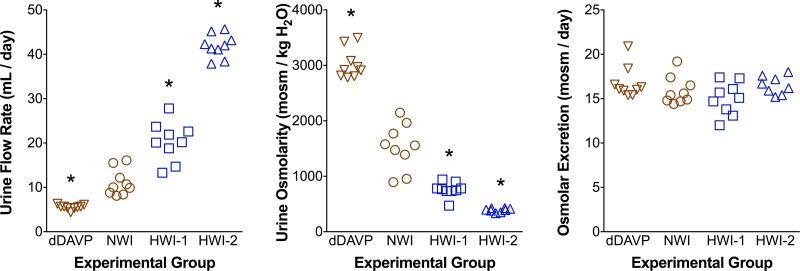

Induction of different levels of urine concentrating activity by manipulating fluid intake.

To study the influence of vasopressin on several aspects of renal function and dysfunction, endogenous secretion of vasopressin may need to be either inhibited or stimulated. In some protocols, a 3% sucrose solution is offered as the sole drinking fluid to reduce vasopressin secretion. This results in a 50% reduction of urine osmolality (and a corresponding increase in urine output) (11) but also in a significant increase in carbohydrate intake (∼1.5 g/day if rats drink 50 ml/day) that influences the secretion of hormones involved in carbohydrate metabolism. The increase in calorie intake via sucrose may also induce some reduction in food intake (and, therefore, reduce intake of protein, vitamins, electrolytes, etc.). These changes may confound any observed changes due to increased water intake. We designed a protocol (13) to manipulate urine osmolality by increasing water intake without adding sucrose by feeding the animals a gel diet with water added to the desired amount of food. All rats had access to drinking water ad libitum. All rats received the same amount of food per day, (equivalent to 18 g/day powder food), an amount slightly lower than what the control group would ingest spontaneously. If this mild restriction were not applied, gel-fed rats (similar to mice) would eat more food than the dry food-fed groups, presumably because moist food is more palatable. As depicted in Fig. 2, we fed rats either a gel diet with 2 or 4 ml water/g food plus 20 mg agar/g food (HWI-1 and HWI-2, respectively), or a dry powder food to which we added 20 mg agar/g (with no water) for 1 wk. An additional group of rats received an intraperitoneal infusion of the selective vasopressin V2 receptor agonist dDAVP (200 ng/day; Ferring, Malmö, Sweden) via an osmotic minipump. We housed rats in metabolic cages for 1 wk and collected urine from the last 3 days (14). As depicted in Fig. 2, total water intake approximately doubled and quadrupled in the HWI-1 and HWI-2 groups, respectively. Urine osmolality decreased proportionately. dDAVP reduced urine flow rate and further increased urine osmolality. Daily osmolar excretion was similar in all groups, as we controlled food intake with mild food restriction, and all animals were in steady state.

Fig. 2.

Gel food is used to vary urine osmolality over a wide range without altering osmolar excretion. Urine flow, osmolality, and osmolar excretion in 4 groups of rats: controls [normal water (NWI)], dDAVP-infused rats with conventional powder food, and rats with enhanced water intake provided by feeding them gel food with 2 or 4 ml water/g food (HWI-1 and HWI-2, respectively). All rats had water ad libitum and received an equivalent of 18 g/day powder food. Each point represents one 24-h urine sample; n = 3 rats/group, each studied on days 5–7 on the different diets. Data from dDAVP, NWI, and HWI-1 groups adapted from Bouby et. al. (4). *P < 0.05 compared with NWI group.

The consequences of an increase in vasopressin secretion have been studied after total water deprivation for 24 or even 48 h while continuing to provide food ad libitum. In such protocols, food intake decreases and fluid losses are not compensated, leading to progressive weight loss (15–20% of body weight in 48 h; see Ref. 10). Moreover, a significant rise in natriuresis is observed during the 1st day of dehydration (12). In addition to being physiologically stressed by the total lack of drinking water (with confounding humoral and sympathetic changes), the animals cannot be studied in steady state. We designed a protocol to reduce daily fluid intake while maintaining steady state (13). We provided each animal with one-third of the previously spontaneous water intake per day via a water bottle. In the example shown in Table 1, we housed adult rats in metabolic cages and provided either only 15 ml water/day for 5 days or an ad libitum water supply. This protocol leads to a new steady state in which food intake is only modestly reduced (by ∼15%) and urine osmolality is significantly increased, yet body weight remains stable. This protocol could be used for a longer duration. In contrast, chronic total water deprivation results in a loss of body weight, progressive lethargy, and leads to death in a few days, and is no longer accepted by animal welfare committees.

Table 1.

Water restriction achieved by providing a limited amount of water per day increases urine osmolality without decreasing body weight in rats

| Ad Libitum Water | Water Restriction | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 296 ± 9 | 292 ± 5 |

| Water intake, ml/day | 23.5 ± 2.0 | 14.2 ± 0.5* |

| Urine flow rate, ml/day | 13.4 ± 1.0 | 6.7 ± 3.0* |

| Urine osmolality, mosm/kg H2O | 1,728 ± 264 | 2,832 ± 180* |

Values are means ± SE of the last day after 5 days on these diets; n = 8 rats/group.

P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test.

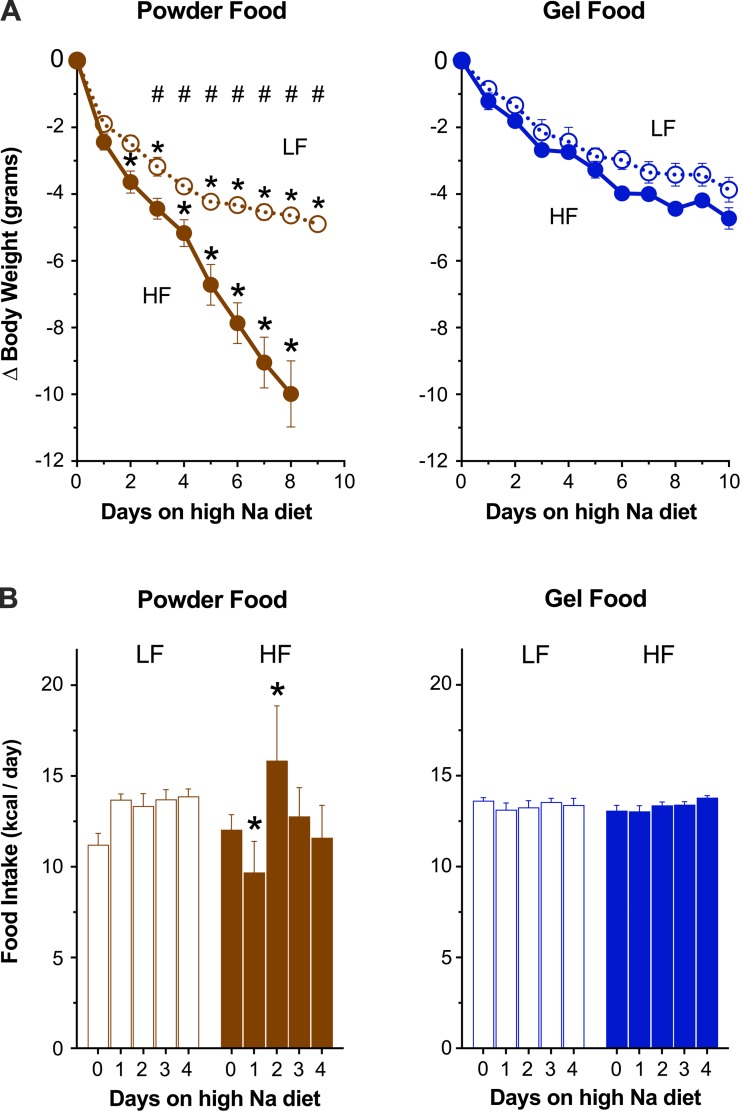

Use of a restricted gel diet in metabolic cages to minimize weight loss in LF- and HF-fed mice.

Unpalatable diets exacerbate the initial weight loss of rodents placed in metabolic cages. To minimize this weight loss, we compared daily food intake and body weight of mice housed in metabolic cages and fed identical diets formulated as powder or gel. We fed four groups diets differing by dietary fat content (LF or HF) and formulation (powder or gel) in a 2 × 2 scheme. We provided powder food ad libitum and gel food with mild food restriction daily. After acclimating the mice to metabolic cages, we transitioned them to high-Na LF or HF diets for ≥4 days. As depicted in Fig. 3, both LF- and HF-fed mice lost significantly less weight on gel food than on powder food. On high-Na diets, HF-fed mice on powder food continued to lose weight daily without evidence of recovery.

Fig. 3.

Gel food improves intake and reduces weight loss in metabolic cages. Influence of food type on cumulative weight loss (A) and food intake (B) in low-fat (LF)- and high-fat (HF)-fed mice when transitioned from normal to high-Na diet in metabolic cages (n = 8 mice/group). *P < 0.05, powder (brown) vs. gel (blue) food; #P < 0.05, LF- vs. HF-fed mice within a diet formulation.

In addition to minimizing weight loss, restricted gel food resulted in more consistent Na intake. Despite identical dietary Na content between gel and powder diets, Na intake differed between LF and HF powder-fed groups but was equivalent in LF and HF gel-fed groups. Intragroup Na intake was less variable in HF gel-fed than in HF powder-fed mice (coefficient of variance 18.1 vs. 2.3% in powder and gel diets, respectively; P = 0.002 by F-test for unequal variance). In summary, gel diets reduce weight loss, reduce intra- and intergroup intake variability, and permit experiments using three combined manipulations: housing in metabolic cages, high dietary fat, and Na content.

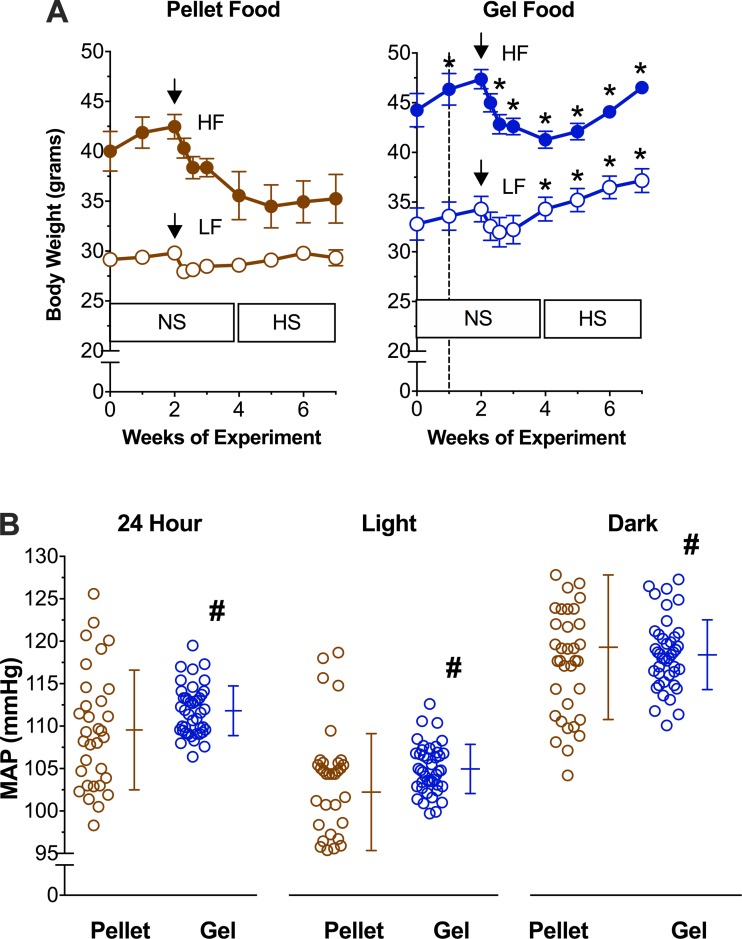

Use of restricted gel diet to reduce weight loss and blood pressure variability in mice.

The stress of surgery results in temporary weight loss and decreased food intake. Variability in food intake may influence blood pressure, particularly on high-Na diets (14). In an attempt to improve recovery from surgery and measure the influence of intake variability on blood pressure, we compared the body weight and mean arterial pressure of mice after radiotelemetric blood pressure catheter implantation (PA-C10; Data Sciences International, New Brighton, MN) when they were fed identical diets formulated as pellets or gel. We fed four groups diets differing by dietary fat content (LF or HF) and diet formulation (pellet or gel) in a 2 × 2 scheme. We fed all groups a normal Na diet before and 2 wk after surgery, and then we transitioned all groups to high-Na diets (data from some of the gel food-fed mice and radiotelemeter implantation protocols were published previously; see Ref. 14). We housed mice in individual standard cages. We measured food intake in gel food-fed mice (dyed blue to contrast with bedding; FD & C Blue Dye No. 1, 0.05% added by Research Diets) but not in pellet-fed mice (pellets can break apart and fall into the bedding). Seven days after telemeter implantation, we sampled mean arterial pressure for 1 min every 10 min for 7 days on a normal Na diet and averaged over each day according to previously published protocols (14). In both LF- and HF-fed mice, gel diets resulted in less weight loss after surgery and more weight gain on a high-Na diet compared with pellet-fed mice (Fig. 4). Importantly, HF-fed mice recovered postsurgical weight loss on a gel diet but not a pellet diet. Four weeks after surgery, pellet HF-fed mice had lost significantly more body weight than gel HF-fed mice (6.3 ± 1.0 vs. 1.1 ± 1.3 g respectively, P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Gel food improves recovery of body weight after surgery and reduces blood pressure variability. A: body weight of mice after surgery and after initiating a high-Na diet on either pellet (brown) or gel (blue) food in LF- (open circles) or HF-fed (solid circles) mice. NS, normal diet; HS, high-Na diet. Dashed line denotes the start of gel food. Black arrow denotes time of surgery. B: mean arterial pressure (MAP) on high-Na diet in pellet- and gel food-fed mice averaged over 24 h and during light and dark periods. Each circle represents the average mean arterial pressure over each of 7 days of recording; n = 7 mice/group. *P < 0.05 pellet vs. gel with each group; #P < 0.05, F-test for unequal variance.

Gel diets also significantly reduced the variability of mean arterial pressure compared with pellet diets. The coefficient of variance of 24-h average mean arterial pressure per mouse per day was 6.3% on the pellet diet and 2.6% on the gel diet (P < 0.05). Mean arterial pressure during light and dark periods of the diurnal cycle also had a significantly decreased coefficient of variance on the gel diet compared with the pellet diet (Fig. 4). To evaluate whether the gel diet improved recovery from surgery, we compared mean arterial pressure during the first 3 days with that during the subsequent 4 days. There was no difference in the coefficient of variance within groups between these time periods (P = 0.57 and 0.65 in pellet- and gel-fed groups, respectively).

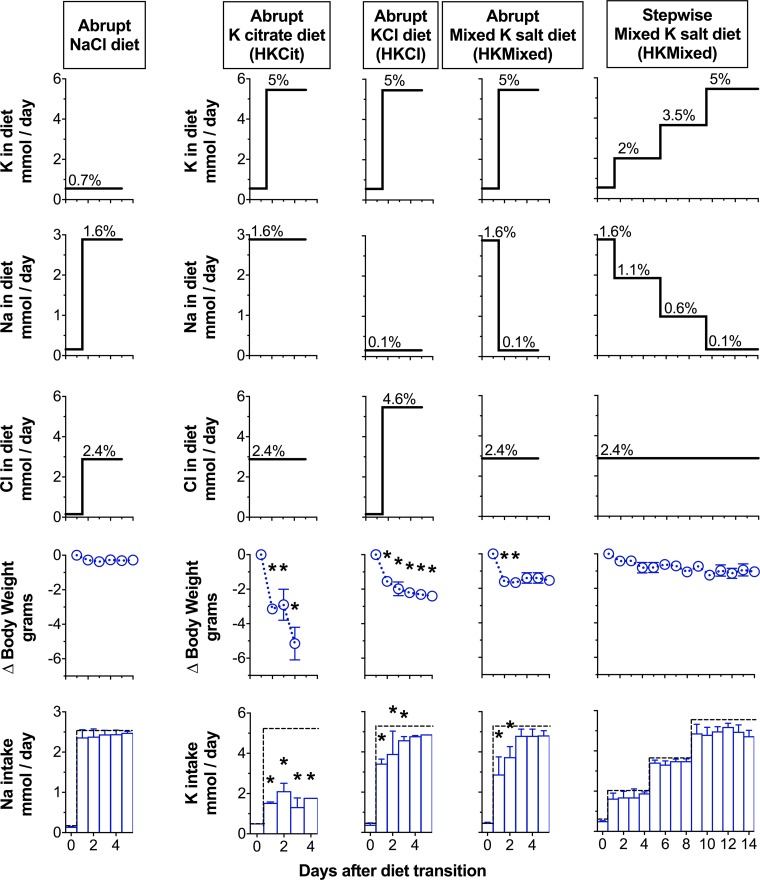

Maintaining food intake and body weight on a stepwise gel-based high-K diet.

High-K diets are commonly 5% wt/wt and occasionally as high as 10%. At such high concentrations, the associated anion (citrate or chloride) may influence acid/base or Na homeostasis, respectively (1, 5). Thus, we compared food intake and body weight in mice fed gel food with different 5% K diets to achieve a high K intake in mice previously on a high-Na chloride diet. The exclusive use of a 5% K chloride to increase the K content significantly increased the chloride content above the high-Na chloride diet that we fed the mice previously. To compare normal vs. high K without a confounding increase in chloride content, we designed diets with K citrate or with a mix of K chloride and K citrate (HKMixed) that substitutes Na chloride with K chloride in a 1:1 molar ratio (Fig. 5). In series, we acclimated four groups of mice to metabolic cages on a high-Na and normal K diet and then transitioned them to a high-K citrate and high-Na chloride (HKCit) diet, a high-K chloride and normal Na (HKCl) diet, and the HKMixed diet transitioned abruptly (Abrupt HKMixed) or with stepwise increases in K content over 8 days (Stepwise HKMixed). We provided all diets with mild food restriction. We used the same content of water (2 ml water/g powder food), K (5% wt/wt if all K added was K chloride, 366 µmol K/kcal), and a high-chloride content (2.4% in HKCit and HKMixed diets, 181 µmol chloride/kcal, and 4.4% in the HKCl diet, 328 µmol chloride/kcal).

Fig. 5.

Stepwise increases in K content improve intake and reduce weight loss on high-K diets. Dietary K (top), Na (second from top), Cl content (middle), change (∆) in body weight (second from bottom), and K intake (bottom) in mice transitioned to a 1.6% Na diet (abrupt NaCl diet; n = 8 mice), a 5% K diet using K citrate (HKCit; n = 4 mice), K chloride (HKCl; n = 4 mice), or mixed K salt diet transitioned abruptly (abrupt HKMixed; n = 6) or gradually (stepwise HKMixed; n = 8 mice). Dotted line indicates daily amount of Na or K presented to each mouse, as indicated. Percentages indicate electrolyte content wt/wt of powder food. *P < 0.05, 2-tailed t-test compared with the stepwise HKMixed group while fed a 5% K diet.

As depicted in Fig. 5, mice housed in metabolic cages tolerate a gel high-Na diet without losing weight (same experiment as Fig. 3). The relative fold change in Na content was 1.7× compared with the target of a 7.1× fold increase in K content. Mice provided the HKCit diet ate less food and continuously lost weight beyond day 3. Therefore, we had to terminate the experiment early. Mice in the HKCl and abrupt HKMixed groups ate less food and lost weight initially, but after 3 days, they ate all the provided food, and further weight loss stopped. Body weights of these mice stabilized after losing an average of 2 g. Mice in the stepwise HKMixed group consistently ate nearly all of the provided food and only lost an average of 1 g of body weight after 14 days in metabolic cages. Food intake on the first day of the 5% K diet was highly consistent across all mice in this group. For all days on the high-K diets, mice fed the stepwise HKMixed diet lost significantly less weight than other high K groups (P < 0.01), and there was no significant difference in body weight or serum bicarbonate (18.6 ± 0.7 g HKMixed vs. 19.4 ± 0.6 high Na alone, P = 0.4) compared with the transition from a normal to high-Na diet.

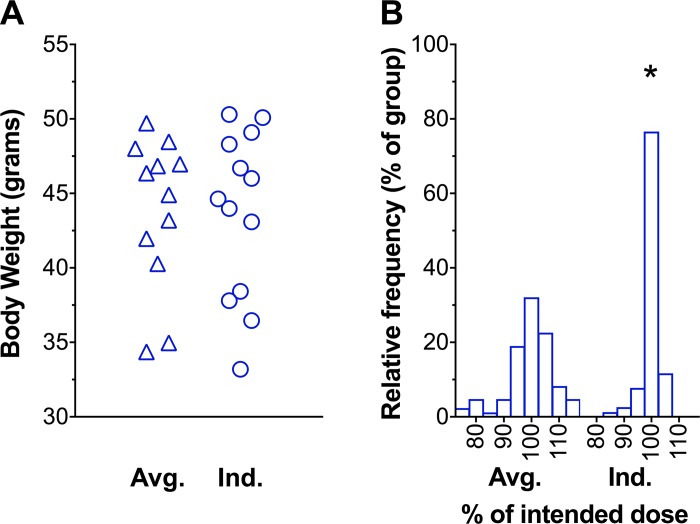

Individualized drug dosing improves precision despite a wide dispersion of body weight.

Experiments comparing blood pressure response to drugs or hormones can be confounded by acute hypertension caused by the stress of injection or gavage or acute hypotension caused by extracellular fluid shifting into the peritoneum if hypertonic solutions are administered (6). We compared two protocols for administering benzamil, an inhibitor of the epithelial sodium channel, in gel food. We fed group cage-housed mice a gel diet with mild food restriction to reduce intragroup variability and then added benzamil to the diet. We administered 1.4 mg benzamil/kg body wt by two strategies: drug concentration adjustment by body weight quartile (averaged protocol) or daily concentration adjustment (individualized protocol). In the averaged protocol, we prepared four separate gel diets, each with a benzamil concentration determined to administer the intraquartile mean body weight-based dose. In the individualized protocol, we prepared two gel diets, one with a drug concentration high enough to administer 1.4 mg benzamil/kg in the largest mouse and the other without drug to replace a fraction of gel food to adjust the total drug dose based on each mouse’s daily body weight.

We determined the drug concentration in the gel food using the following equation:

Using calorie restriction, grams of gel consumed should be the total daily food allowance. In the individualized group, we calculated the amount of food to be replaced using the following equation:

further expanding this equation,

Replaced gel food was a small fraction of the total food and placed at the center of the gel surface so that mice eat the non-drug-containing food first, and any remaining food will be drug-containing food.

We adjusted gel food daily to tailor the dose to mice with changing body weight over the period of drug administration.

At the end of each day, we calculated the administered dose by the following equation:

We then adjusted this amount of gel food consumed for evaporation of water from any uneaten food.

Figure 6A depicts the similar distribution of body weights between average and individualized protocols. Figure 6B illustrates a lower variability of delivered dose using the individualized protocol. Coefficient of variance was 8.1 and 4.4% in the average and individualized protocols, respectively (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 6.

Individualized protocol improves precision of weight-based drug administration. A: mean body weight of mice during the 7 days of drug administration. B: frequency distribution of delivered dose. Averaged protocol (Avg.), n = 12 mice; individualized protocol (Ind.), n = 13 mice. *P < 0.0001, F-test for unequal variance between protocols.

DISCUSSION

Gel food and mild food restriction.

Laboratory rodents are usually fed pellets (in group cages) or powdered food (in individual metabolic cages). These foods have a very low water content (<10%). Although pragmatic for distribution and storage, it is not possible to vary nutritional components or drugs and distribute them evenly throughout the food. A liquid diet has been marketed, but is relatively expensive and has not been widely used (18). In 1990, in experiments lasting several weeks in rats, Bouby et al. (4) introduced a gel food preparation that is based on the addition of water and a small amount of agar to the powder diet. Other authors have since used gel food in the same way (16) but have not directly compared this technique with conventional powder or pellet food.

In this series of experiments, we demonstrate that rats tolerate changes in water content and mice tolerate high-Na, high-K, and HF diets formulated as gel food that are poorly tolerated as powder or pellets. Gel foods also facilitate the more accurate control and measurement of food intake. Mice cannot eat powder food without dropping it into the bedding of standard cages or the urine collection systems of metabolic cages, preventing the control and measurement of intake. Similarly, pellet food crumbles and falls into cage bedding, presenting the same limitations. We used dyed gel food to detect any dropped food apparent within the cage bedding or urine collection system. Under mild food restriction, mice ingest the entire daily allotment of food, preventing contamination of collected urine and allowing precise control and measurement of intake. Pair feeding, consisting of measuring the weight of food eaten on one day and providing the same amount to the other group on the next day, also provides some control but is tedious and prevents the synchronous exposure of mice to treatments.

A significant decline in food intake indirectly increases renal Na and K retention, potentially disrupting the steady-state assumptions between groups and introducing bias. We measured this bias by comparing LF- and HF-fed mice. HF-fed mice consume less powder food and consequently less Na. Therefore, a measurement of Na avidity in LF- vs. HF-fed mice is confounded by differences in Na intake. Use of gel food returned intake to levels comparable with LF-fed mice (14), abrogating this bias. These results are of particular relevance to studies using HF feeding for diet-induced obesity, wherein weight loss also reduces insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and inflammation.

Several considerations are warranted when using gel diets. Mice will dislodge unpalatable food from the dish, further restricting intake and causing more weight loss than in ad libitum powder or pellet diets. Dislodged food falls onto the urine collection system, which can reduce the collected urine volume and contaminate the urine. We have observed that mild food restriction and partially covering food dispensers may partially prevent this behavior. Gel food also spoils quickly at room temperature and needs to be replaced daily. Moreover, if gel food is not completely consumed, evaporation from uneaten food results in overestimation of solute intake and underestimation of water intake. A brief control experiment yields the data needed to compensate for evaporation. Additionally, heating food higher than 65°C may degrade thiamine (9), a vitamin included in all rodent diets. If agarose is given in large amounts, it can cause an osmosis-related increase in stool water content, as it remains undigested. Gel diets with >3 ml water/g food can cause watery stool and contaminate urine collections.

Water control.

In experiments designed to chronically manipulate the level of vasopressin and/or of urine concentrating activity, care must be taken to study animals in steady state and to avoid introducing confounding factors. Total water deprivation, AVP, or dDAVP infusions lead to different pathophysiological situations. Water deprivation increases vasopressin secretion but leads to a situation that worsens over hours and days and causes severe stress and Na excretion and thus may change many hormones or mediators in addition to vasopressin. The reduction in food intake associated with the lack of drinking water leads to a reduction in osmolar excretion and thus invalidates comparison of renal function between water-deprived and control groups. As described above, vasopressin secretion and the resulting urine concentrating activity achieved by a controlled water limitation provide a more satisfactory experimental condition than total water deprivation because animals reach a new balance with lower water consumption, lower urine volume, and higher urine osmolality, and can be studied in steady state for a longer period of time.

Chronic AVP or dDAVP exposure, used in a number of studies, results in different situations. Vasopressin stimulation or infusion will stimulate V1a, V1b, and V2 receptors. Renal V1a receptor-mediated effects have been shown to partially counteract the antidiuretic and antinatriuretic effects mediated by V2 receptor activation (15). This explains why AVP, above a certain threshold, becomes diuretic and natriuretic despite its known effects on ENaC and resulting Na reabsorption. dDAVP, a highly selective V2 receptor agonist, will retain water and thus reduce endogenous vasopressin secretion, thus reducing V1a and V1b receptor-mediated actions. For this reason, it is inaccurate to conflate the effects of dDAVP effects with those of vasopressin. Upon normal vasopressin release in vivo, only selective V2 receptor-mediated antidiuretic effects occur for very low concentration of the hormone (15).

To reduce vasopressin secretion and lower urine osmolality, providing sucrose as drinking fluid increases fluid intake and urine output and presumably reduces vasopressin secretion (although this has not been directly evaluated, to our knowledge). However, it also increases carbohydrate and calorie intake that undoubtedly modifies the secretion of insulin and glucagon (and possibly other hormones and gut-derived mediators). These confounding factors are usually not addressed in the interpretation of results. As described above, a more appropriate protocol is achieved, in which only the amount of water ingested is increased by adding water to gel food. The amount of water can be varied over a wide range (from 0.5 to 3 ml water/g food), thus leading to adjustable reductions in urine osmolality. Water addition via gel food can also be useful in a converse scenario. In a study of UT-B−/− mice, which have a urinary concentrating defect, the authors used gel food to administer more water to wild-type mice, so as to reduce their urine osmolality to that of UT-B−/− mice before an experimental intervention (2). We did not design the water balance experiments to compare the intra- and intergroup variability between a gel and a conventional sucrose diet. However, we believe this study demonstrates the feasibility of avoiding the confounding factors inherent in a sucrose diet while allowing precise control of food and water intake and, therefore, urine osmolality.

Blood pressure.

The use of restricted gel food resulted in less intragroup variability in mean arterial pressure. This is a critical issue given the high cost of radiotelemetry and the resistance to changes in BP seen in C57BL/6 mice compared with other mouse strains and rats (7). We observed an association between higher Na intake and blood pressure variability in pellet-fed compared with gel-fed mice. Because gel food influences intake in several ways, the responsible factors are not known but may include reduced variability of Na or food intake, increased water intake, and less stress from a more palatable diet.

Electrolyte intake.

Diets with high Na and K content can reduce food intake and influence both electrolyte excretion and body weight. In high-K diets, we observed that both the accompanying anion and the magnitude of the change in K concentration affect food intake and body weight. Several groups increase the K content in diets using a combination of K citrate and K chloride (8, 19) similar to the formulation used in the HKMixed groups in our experiments. Conventional feeding can be a source of significant confounding due to both weight loss and variable intake during the first several days of Na- or K-rich diets. For high-K diets, the specific anion used and a stepwise increase can largely attenuate these undesirable effects.

Oral weight-based drug administration using gel preparations.

The individualized protocol for precise weight-based drug dosing via gel food is useful for reducing intra- and intergroup variability and for blood pressure measurement. Administration of drugs via injection or gavage can acutely change blood pressure (17), and administration via water ad libitum does not allow for control of the dose and results in an obligatory link between drug intake and water intake. The use of gel food for orally bioavailable drugs can be custom-delivered to rodents without the production of expensive, commercially produced powder or pellets. In a similar, previously published strategy to administer a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist to rats (3), investigators used gel food with 10-fold drug concentration to replace a small amount of gel food with a drug concentration targeting the smallest animal. Our protocol is limited by the timing of food administration over the 24-h period, although the majority of the drug is consumed after 4–6 h during the dark phase of the diurnal cycle (unpublished observations).

Limitations.

We used only male rats and mice in the present experiments. However, it can be assumed that the proposed protocols would work equally well in animals of both sexes.

Conclusions.

Metabolic balance and blood pressure experiments are fraught with technical complications and can be statistically underpowered if changes in feeding or other behaviors increase intra- or intergroup variability. We show here that the use of gel food feeding and additional modifications such as mild food restriction, stepwise increases in electrolytes, and individualized drug delivery overcome many of these challenges. We demonstrate the utility of these methods for precise water, Na, K, high-fat, and drug delivery and welcome the widespread adaptation of these methods for renal physiology and pathophysiology experiments.

GRANTS

J. M. Nizar received support from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK; 1-K08-DK-114567-01). J. M. Nizar was previously supported by an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (16POST27770003) and the Tashia and John Morgridge Endowed Postdoctoral Fellowship and Child Health Research Institute at Stanford University, and Stanford Clinical and Translational Science Awards (UL1-TR-001085). V. Bhalla received support from the NIDDK (1-R01-DK-091565). V. Bhalla and L. Bankir received support from the France-Stanford Center for Interdisciplinary Studies. N. Bouby has no support to declare.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M.N., N.B., L.B., and V.B. conceived and designed research; J.M.N. and N.B. performed experiments; J.M.N., N.B., L.B., and V.B. analyzed data; J.M.N., N.B., L.B., and V.B. interpreted results of experiments; J.M.N. prepared figures; J.M.N. and L.B. drafted manuscript; J.M.N., N.B., L.B., and V.B. edited and revised manuscript; J.M.N., N.B., L.B., and V.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Wuxing Dong, Ming Ming Lu, Nona Velarde, Yanli Qiao, and Elizabeth Walczak for technical assistance with experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amorim JB, Bailey MA, Musa-Aziz R, Giebisch G, Malnic G. Role of luminal anion and pH in distal tubule potassium secretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F381–F388, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00236.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bankir L, Chen K, Yang B. Lack of UT-B in vasa recta and red blood cells prevents urea-induced improvement of urinary concentrating ability. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F144–F151, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00205.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardoux P, Bruneval P, Heudes D, Bouby N, Bankir L. Diabetes-induced albuminuria: role of antidiuretic hormone as revealed by chronic V2 receptor antagonism in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1755–1763, 2003. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouby N, Bachmann S, Bichet D, Bankir L. Effect of water intake on the progression of chronic renal failure in the 5/6 nephrectomized rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 258: F973–F979, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.4.F973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castañeda-Bueno M, Cervantes-Perez LG, Rojas-Vega L, Arroyo-Garza I, Vázquez N, Moreno E, Gamba G. Modulation of NCC activity by low and high K+ intake: insights into the signaling pathways involved. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F1507–F1519, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00255.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frindt G, Palmer LG. Effects of insulin on Na and K transporters in the rat CCD. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F1227–F1233, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00675.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartner A, Cordasic N, Klanke B, Veelken R, Hilgers KF. Strain differences in the development of hypertension and glomerular lesions induced by deoxycorticosterone acetate salt in mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1999–2004, 2003. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holtzclaw JD, Cornelius RJ, Hatcher LI, Sansom SC. Coupled ATP and potassium efflux from intercalated cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F1319–F1326, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00112.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kandutsch AA, Baumann CA. Factors affecting the stability of thiamine in a typical laboratory diet. J Nutr 49: 209–219, 1953. doi: 10.1093/jn/49.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J, Williams PG. The effect of vasopressin (Pitressin) administration and dehydration on the concentration of solutes in renal fluids of rats with and without hereditary hypothalamic diabetes insipidus. J Physiol 220: 729–743, 1972. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim SW, Han KH, Jung JY, Kim WY, Yang CW, Sands JM, Knepper MA, Madsen KM, Kim J. Ultrastructural localization of UT-A and UT-B in rat kidneys with different hydration status. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R479–R492, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00512.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinley MJ, Denton DA, Nelson JF, Weisinger RS. Dehydration induces sodium depletion in rats, rabbits, and sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 245: R287–R292, 1983. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.245.2.R287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicco C, Wittner M, DiStefano A, Jounier S, Bankir L, Bouby N. Chronic exposure to vasopressin upregulates ENaC and sodium transport in the rat renal collecting duct and lung. Hypertension 38: 1143–1149, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.092641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nizar JM, Dong W, McClellan RB, Labarca M, Zhou Y, Wong J, Goens DG, Zhao M, Velarde N, Bernstein D, Pellizzon M, Satlin LM, Bhalla V. Na+-sensitive elevation in blood pressure is ENaC independent in diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F812–F820, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00265.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perucca J, Bichet DG, Bardoux P, Bouby N, Bankir L. Sodium excretion in response to vasopressin and selective vasopressin receptor antagonists. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1721–1731, 2008. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiwari S, Halagappa VK, Riazi S, Hu X, Ecelbarger CA. Reduced expression of insulin receptors in the kidneys of insulin-resistant rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2661–2671, 2007. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiwari S, Sharma N, Gill PS, Igarashi P, Kahn CR, Wade JB, Ecelbarger CM. Impaired sodium excretion and increased blood pressure in mice with targeted deletion of renal epithelial insulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 6469–6474, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711283105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verbalis JG. Hyponatremia induced by vasopressin or desmopressin in female and male rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1600–1606, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen D, Cornelius RJ, Rivero-Hernandez D, Yuan Y, Li H, Weinstein AM, Sansom SC. Relation between BK-α/β4-mediated potassium secretion and ENaC-mediated sodium reabsorption. Kidney Int 86: 139–145, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]