Abstract

Reloading of atrophied muscles after hindlimb suspension unloading (HSU) can induce injury and prolong recovery. Low-impact exercise, such as voluntary wheel running, has been identified as a nondamaging rehabilitation therapy in rodents, but its effects on muscle function, morphology, and satellite cell activity after HSU are unclear. This study tested the hypothesis that low-impact wheel running would increase satellite cell proliferation and improve recovery of muscle structure and function after HSU in mice. Young adult male and female C57BL/6 mice (n = 6/group) were randomly placed into five groups. These included HSU without recovery (HSU), normal ambulatory recovery for 14 days after HSU (HSU+NoWR), and voluntary wheel running recovery for 14 days after HSU (HSU+WR). Two control groups were used: nonsuspended mouse cage controls (Control) and voluntary wheel running controls (ControlWR). Satellite cell activation was evaluated by providing mice 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) in their drinking water. As expected, HSU significantly reduced in vivo maximal force, decreased in vivo fatigability, and decreased type I and IIa myosin heavy chain (MHC) abundance in plantarflexor muscles. HSU+WR mice significantly improved plantarflexor fatigue resistance, increased type I and IIa MHC abundance, increased fiber cross-sectional area, and increased the percentage of type I and IIA muscle fibers in the gastrocnemius muscle. HSU+WR mice also had a significantly greater percentage of BrdU-positive and Pax 7-positive nuclei inside muscle fibers and a greater MyoD-to-Pax 7 protein ratio compared with HSU+NoWR mice. The mechanotransduction protein Yes-associated protein (YAP) was elevated with reloading after HSU, but HSU+WR mice had lower levels of the inactive phosphorylated YAPserine127, which may have contributed to increased satellite cell activation with reloading after HSU. These results indicate that voluntary wheel running increased YAP signaling and satellite cell activity after HSU and this was associated with improved recovery.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Although satellite cell involvement in muscle remodeling has been challenged, the data in this study suggest that voluntary wheel running increased satellite cell activity and suppressed Yes-associated protein (YAP) protein relative to no wheel running and this was associated with improved muscle recovery of force, fatigue resistance, expression of type I myosin heavy chain, and greater fiber cross-sectional area after disuse.

Keywords: atrophy, fatigue, muscle disuse, muscle fibers, running exercise, satellite cells, Yes-associated protein

INTRODUCTION

Muscle atrophy, whether occurring from a primary cause such as unloading (i.e., microgravity, bed rest, or inactivity) or from muscle loss that is secondary to changes in age, nutrition, or disease, results in an inherent loss of muscle function and strength that contributes to mobility impairment and decreased quality of life (8, 9, 11, 18, 30, 44). Although there is a high degree of muscle plasticity during atrophy and recovery from disuse (2, 10, 17, 22, 52), identification of therapeutic targets that improve the recovery of muscle mass and function during the reloading phase following muscle wasting has proven to be illusive.

Muscle disuse atrophy is characterized by decrements in muscle force, mass, and muscle fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) and a phenotypic shift of an oxidative myosin heavy chain (MHC) profile (type I and type IIa) to a more glycolytic composition (type IIb/x) (20, 34, 51). Aerobic exercise induces a type IIb/x-to-type I/IIa fiber type switch in muscle, identifying it as a potential rehabilitative tool for improving fatigability during recovery from disuse atrophy (22, 28, 41). However, atrophied muscles are susceptible to injury, and exercise can cause further damage and delay recovery (28, 43, 54). In contrast, 7 days of voluntary wheel running after hindlimb suspension unloading (HSU) was reported to improve muscle mass, CSA, and fatigue resistance without causing detrimental damage to the muscles compared with a no-running group, but the effects of longer-duration (e.g., 14 days) exercise on either satellite cell activation or the fiber type profile are unknown (22). Nevertheless, voluntary wheel running appears to be a viable approach for investigating exercise during reloading without causing debilitating damage.

Multiple mechanisms contribute to HSU-induced atrophy and recovery, but there is a lack of consensus on which mechanisms are the most important (14, 15, 17, 38, 40, 41). One of the proposed mechanisms is satellite cell-mediated recovery after muscle atrophy. Satellite cells are quiescent muscle stem cells that lie between the basal lamina and sarcolemma of myofibers. They are known to be essential for muscle growth and repair (53), and several studies have suggested that satellite cells might also be important in the management of unloading recovery (1, 2, 6–8, 11, 13, 33). Furthermore, HSU has been shown to inhibit satellite cell proliferation (15). However, one study reported that the initial phase of recovery is not dependent on satellite cell proliferation (26). Nevertheless, it is unknown whether elevated satellite cell proliferation would improve early recovery or if it drives later recovery from muscle disuse. As voluntary wheel running has been shown to increase satellite cell proliferation during normal loading without injury (24, 29, 31), we chose to utilize voluntary wheel running to examine the relationship between satellite cell proliferation and muscle recovery after disuse. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to determine whether voluntary wheel running activated satellite cells and enhanced functional and morphological recovery from muscle disuse following HSU in mice. As Hippo signaling is a conserved pathway that is thought to regulate cell proliferation, apoptosis, and stem cell self-renewal in many tissues and the Yes-associated protein (YAP) of this pathway is regulated by mechanical sensing in muscle (19) (perhaps loading), as a secondary aim we also sought to determine whether wheel running would regulate YAP in skeletal muscle as a means to modulate satellite cell proliferation during reloading.

In this study, we chose to examine satellite cell and YAP signaling in the largely fast myosin-containing gastrocnemius muscle. While it is true that hindlimb suspension-induced muscle loss is greater in muscles that contain a high type I fiber content, it is also true that hindlimb suspension-induced muscle loss causes significant reductions in muscle mass and function in muscles that highly express type II MHC. Furthermore, bed rest, aging, and other models of unloading or disuse show loss in muscles of both type I and type II MHC composition, and this also includes an elevation of oxidative stress (1, 2, 7, 10, 23, 46, 49, 50, 52). We have used the plantarflexor muscles to study muscle unloading because less is known about how the fast-contracting muscles respond to unloading. The plantarflexors are the most important for running, and, at least in terms of function, the gastrocnemius is the major contributor to plantarflexion both in running and in muscle functional assessments. Thus, we believe that the fast-contracting muscles such as the major plantarflexors like the gastrocnemius muscles are very relevant to the study of disuse and remodeling. Furthermore, slow muscles like the soleus have more nuclei and more satellite cells than faster-contracting muscles, and therefore it was important to know whether the fast-contracting muscles would respond in a robust manner to reloading after the unloading period even when they had fewer satellite cells than type I fibers as a baseline.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model.

Young adult (4–5 mo of age) male and female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories and housed in animal facilities at West Virginia University that were accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC). The mice were randomly assigned to five groups (n = 6/group): 14 days of normal weight bearing (Control), 14 days of HSU (HSU), 14 days of HSU + 14 days of reambulation (HSU+NoWR), 14 days of voluntary wheel running (ControlWR), or 14 days of HSU + 14 days of voluntary wheel running (HSU+WR). Although there were some small differences in body weight between males and females, this was not marked, and at this age group the animals were considered to be a homogeneous group and representative of the responses of the pooled animals. This project was not designed to evaluate sex as a separate variable, and therefore we pooled the data to provide a representative response from the muscles of both sexes. Considering that both men and women undergo disuse- and spaceflight-regulated muscle wasting, we believe that it was important to have both sexes represented in each experimental population group that was studied.

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was provided in the drinking water (0.8 mg/ml) during the final 14 days of the experiment to measure satellite cells that underwent proliferation during reloading after HSU. Mice were housed individually on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. Animal care standards were maintained by adhering to the recommendations for the care of laboratory animals advocated by the AAALAC and by following the policies and procedures detailed in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US Department of Health and Human Services and proclaimed in the Animal Welfare Act (PL89-544, PL91-979, and PL94-279). All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of West Virginia University.

Hindlimb suspension unloading.

HSU was conducted for 14 days as described previously (1–3, 7, 23, 39). Briefly, the hindlimb muscles of mice were unloaded by adhering orthopedic tape to the tail, which was attached to a metal swivel at the top of the cage, allowing for 360° of rotation and movement. The hindlimbs of mice were elevated, using tail suspension to create a maximal torso angle of 30° with respect to the floor of the cage. Mice were monitored daily. HSU+NoWR and HSU+WR mice were reloaded by removing the tail suspension and allowing normal cage ambulation. HSU+WR mice were additionally provided with a running wheel during reloading. Mice had unrestricted access to food and water throughout the HSU and recovery periods.

Voluntary wheel running.

After 14 days of normal cage activity or HSU, mice in the ControlWR and HSU+WR groups had their cages mounted with running wheels (catalog no. 0297-0050, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). Control and HSU+NoWR mice were housed in identical cages but without running wheels.

Investigation of hindlimb muscles.

Much is known about the preferential atrophy of type I fibers in response to unloading, but far less is known about the impact that unloading and disuse have on type II-fibered muscles. Nevertheless, we have found that while hindlimb unloading results in marker loss of mass and function in muscles that have a high type I fiber composition, fast-contracting muscles with a high type II MHC composition are also markedly affected by disuse, aging, unloading, and reloading (see, e.g., Refs. 7, 8, 13, 14, 17, 20–23, 40). In addition, 10 days of spaceflight has been shown to induce marked atrophy in fast myosin-containing muscles (20). Furthermore, along with type I fibers, type II fibers appear to undergo significant atrophy during spaceflight in humans (24, 25), and therefore examining the ability of muscles with a high type II fiber population, such as the gastrocnemius muscle, to recover after unloading is both relevant and important.

In vivo isometric force measurements.

The effects of the treatments on muscle function were measured by in vivo plantarflexor isometric maximal force and fatigue contractions as described previously (35, 45, 46). Briefly, measurements were taken at day (D)0, D14, D21, and D28 (Fig. 1). Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of 97% oxygen and 3% isoflurane gas and placed on a plate heated to 37°C to maintain body temperature. The right hindlimb was then immobilized with the right ankle positioned at 90° flexion and secured to the footplate of the dynamometer (model 6350*358; Cambridge Technology, Aurora Scientific, Aurora, ON, Canada). Subcutaneous platinum electrodes were placed on either side of the tibial nerve to activate plantarflexor muscles. Maximal force was measured by six sequential electrical impulses (10 Hz, 25 Hz, 50 Hz, 75 Hz, 100 Hz, and 125 Hz) with 3 min of rest between each tetanic contraction. Contractile data were analyzed off-line (Dynamic Muscle Analysis software; Aurora Scientific). Previous pilot experiments in our laboratory demonstrated that stimulation of the tibial nerve in the popliteal fossa activates the plantarflexors and not dorsiflexor muscles. We have previously verified this by pilot studies that stimulated the tibial nerve before and after sectioning of the common peroneal nerve and verified that no dorsiflexion occurred with this protocol (data not shown).

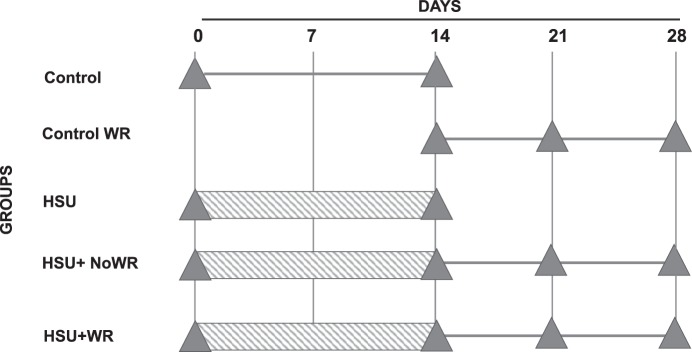

Fig. 1.

Research design: timeline of conducted experiments. Hatched bars indicate HSU. Triangles indicate when in vivo maximum force and fatigue measurements were taken. Exercised animals were introduced to running wheels on D14.

Five minutes after the final tetanic contraction, muscle fatigue was assessed with a modified Burke protocol (12). This consisted of a subsequent set of 180 contractions (40 Hz; 0.1-s duration with 200-µs pulse width). Contractile data were analyzed off-line (Dynamic Muscle Analysis software; Aurora Scientific). Force data from the fatigue test were normalized to the initial contraction force and plotted for each contraction. The slope of the linear portion of the force decline response on the fatigue curve was used to estimate the rate of muscle fatigue.

Body mass and tissue preparation.

Mice were weighed before in vivo force measurements (D0, D14, D21, and D28). Gastrocnemius muscles were removed from the left hindlimb while the animals were deeply anesthetized, and then the mice were euthanized by myocardial extraction. The gastrocnemius muscles were blotted to remove excess fluid and weighed. The left gastrocnemius muscle was mounted on cork and pinned at the optimal muscle length in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT, Tissue-Tek; Andwin Scientific, Addison, IL), frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled methylbutane, and stored at −80°C until being sectioned for immunohistochemistry. After cryosectioning, the left gastrocnemius muscle was removed from the OCT and processed for Western blotting.

Immunohistochemistry.

Frozen 10-µm sections were obtained on a cryostat (CM3050 S; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) from the midbelly of the gastrocnemius muscles. Tissue sections were placed on charged microscope slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), air-dried, and stored at −20°. For BrdU/dystrophin detection, the tissue sections were fixed in methanol-acetone (1:1) and permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X. The sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then incubated in 2 N HCl for 1 h at 37°C, and then neutralized with borate buffer. Nonspecific protein detection was blocked with 10% normal goat serum (S-1000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h before overnight incubation of primary mouse antibodies for BrdU [G3G4; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), Iowa City, IA] and dystrophin (MANDYS8; DSHB) at 4°C. After washing in PBS, tissues were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies for 2 h and mounted on coverslips. BrdU/dystrophin sections were imaged with a Nikon Eclipse E800 upright microscope. BrdU-positive nuclei that were inside the dystrophin-positive muscle fiber were counted with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

For fiber type detection, the tissue sections were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (S-1000; Vector Laboratories) for 1 h before overnight incubation of primary mouse antibodies for dystrophin (MANDYS8; DSHB) and the following MHCs: type I MHC (BA-D5; DSHB), type IIa MHC (SC-71; DSHB), and type IIb MHC (BF-F3; DSHB). Tissue sections were imaged with a VS120 Virtual Slide Microscope (Waltham, MA), and fiber number and CSA were obtained with NIS-Elements software.

As a second measurement to BrdU, satellite cell number was estimated from Pax 7-positive myonuclei. To do this, tissue cross sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in an anti-Pax 7 antibody (DSHB). The following day, the tissue was incubated in an anti-dystrophin antibody (MANDYS8; DSHB) to identify the boundaries of each fiber. Thereafter, the tissue sections were counterstained with DAPI to visualize all of the myonuclei. Satellite cells (Pax 7-positive nuclei) that were adjacent to the muscle sarcolemma were quantified and expressed as Pax 7 nuclei/fiber.

As HSU and voluntary wheel running elicit greater responses in oxidative fiber types, we identified areas within the gastrocnemius muscle cross sections that contained higher oxidative fiber compositions as described previously (21). Rather than regional selections of fibers, the entire gastrocnemius was measured in other assays.

Western immunoblots.

Tissue samples were prepared with procedures described previously (1, 2, 7, 23). Approximately 75 µg of muscle was homogenized in 200 µl of ice-cold RIPA buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris; pH 7.4) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (catalog no. P8340; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and phosphatase inhibitors (catalog nos. P2850 and P5726; Sigma-Aldrich). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and measured for protein content (catalog no. 500-0116; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Fifty micrograms of protein was loaded into each well of a 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gel (catalog no. NP0335BOX; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and separated by routine sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) for 1 h at 150 V. The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for 1.5 h at 30 V or by semidry blot transfer at 15 V for 45 min. Nonspecific protein binding was blocked by incubating the membranes in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST). The membranes were incubated (1:1,000) overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies for Pax 7 (no. ab187339; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), MyoD (no. 554130; BD PharMingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ), YAP (no. 14912; Cell Signaling), phospho-YAP (Ser127) (no. 13008; Cell Signaling), and GAPDH (no. MA5-15738, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Western blots were conducted to determine MHC protein abundance changes with type I MHC (DSHB no. BA-D5), type IIa MHC (DSHB no. SC71), and type IIb MHC (DSHB no. F-F3) antibodies. The membranes were then washed in TBST and incubated in the appropriate secondary antibodies (1:5,000; diluted in 5% nonfat milk), which were conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA).The signals were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (catalog no. 34075; Thermo Scientific), and the corresponding signals were assessed with a G:Box Bioimaging System (Syngene, Frederick, MD). Band intensity was normalized to GAPDH with ImageJ software (NIH).

Verification of antibody specificity.

All antibodies utilized in our experiments were validated before utilization. We used antibodies that were supplied from vendors that were able to provide validation, maintenance testing, and production validation to ensure that lots remained consistent over the course of our study. Additional validation included testing on appropriate positive protein controls or mouse models (deficient in gene/protein) by immunoblot and immunostaining. Western blots were conducted in each antibody to validate band sizes, and nonspecific staining was evaluated in tissue sections by immunohistochemistry. Multiple antibodies to the same protein were used to confirm staining patterns and/or location of the protein band on a Western blot. Appropriate negative controls were conducted (without the primary and subsequently without the secondary antibody) to ensure there was no cross labeling by the antibodies.

Statistical analysis.

Results are reported as means ± SE. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) using one-way ANOVA. Tukey post hoc analyses were performed if significance was detected. Significance was established at P ≤ 0.05 unless otherwise denoted.

RESULTS

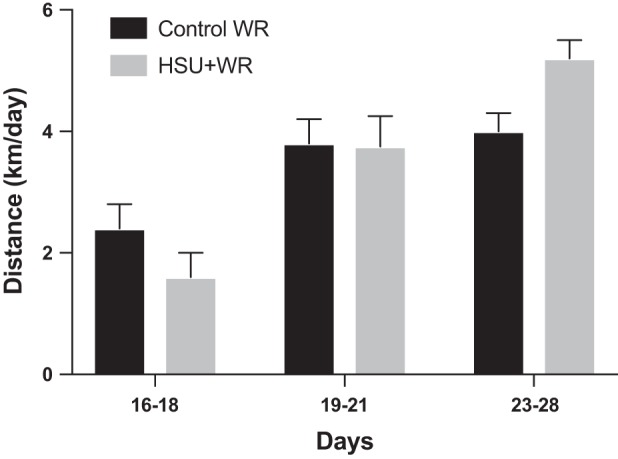

Voluntary wheel running.

Voluntary wheel running was measured daily beginning on D15 (Fig. 2). Running occurred nearly exclusively during the 12-h dark cycle. Data were excluded from D15 and D22, as in vivo maximum force and fatigue measurements were taken during the preceding light cycle (D14, D21). The HSU+WR group ran only 56% of the distance that ControlWR mice ran during D16–D18, although this difference was not statistically different between the groups (P = 0.13). This observation was consistent with other data for reloading atrophied muscles in mice (22). After the initial reloading, the HSU+WR group ran equidistant to the ControlWR group, which is consistent with other data (22).

Fig. 2.

Voluntary wheel running. Average wheel running for ControlWR and HSU+WR (n = 6/group). Mice were given access to running wheels on D15–D28 after 14 days of normal cage activity or HSU. Data are excluded from D15 and D22 because of in vivo force testing. Values are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. Significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Body and gastrocnemius mass.

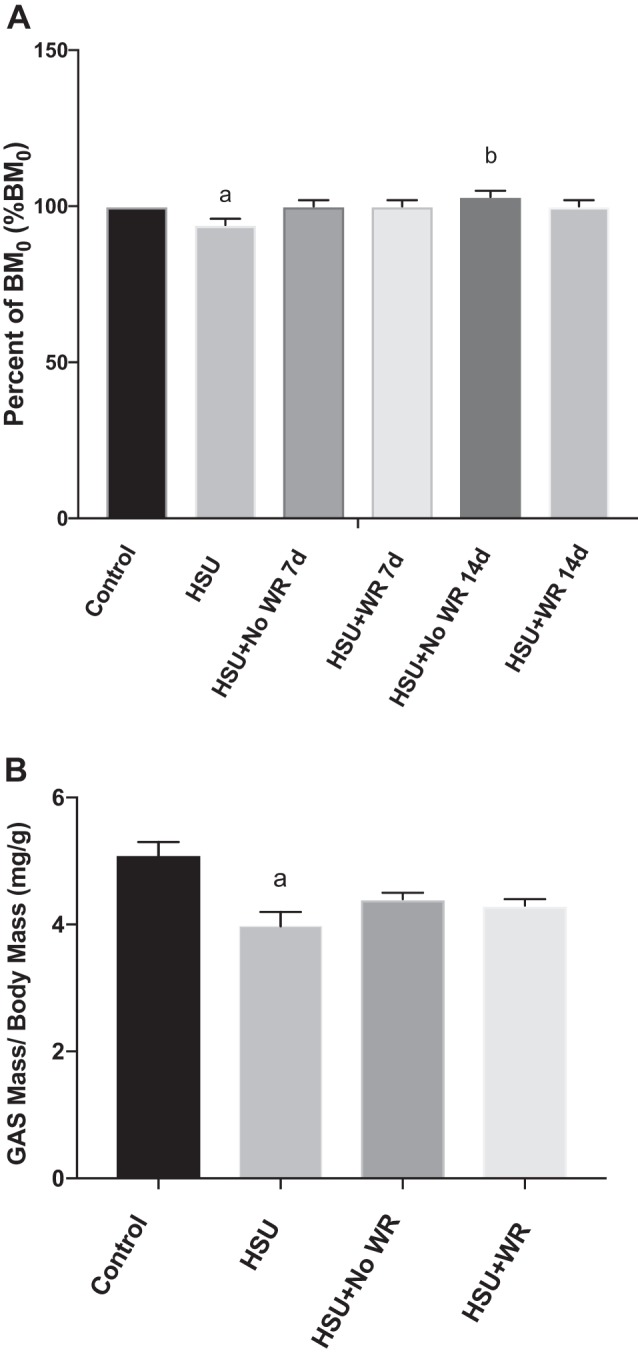

Two weeks of HSU resulted in significant decreases in body mass (BM) (Fig. 3A) and in gastrocnemius muscle weight (Fig. 3B). BM was normalized to the initial BM value, and gastrocnemius weight was normalized to terminal BM. There was no detectable change in BM or gastrocnemius muscle weight from initial values by D7 of recovery for both the HSU+NoWR and HSU+WR groups.

Fig. 3.

Body and gastrocnemius mass. A: body mass (BM) normalized to initial BM (BM0). Fourteen days of HSU resulted in a decreased BM. BM recovered by D7 in both HSU+NoWR (n = 6) and HSU+WR (n = 6). B: gastrocnemius (GAS) mass normalized to BM. Two-wk HSU resulted in decreased gastrocnemius mass that recovered by D7 in both HSU+NoWR (n = 6) and HSU+WR (n = 6). Values are presented as means ± SE. aP ≤ 0.05 vs. Control; bP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU. Statistical analysis was performed by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test.

Maximum force and fatigue rate.

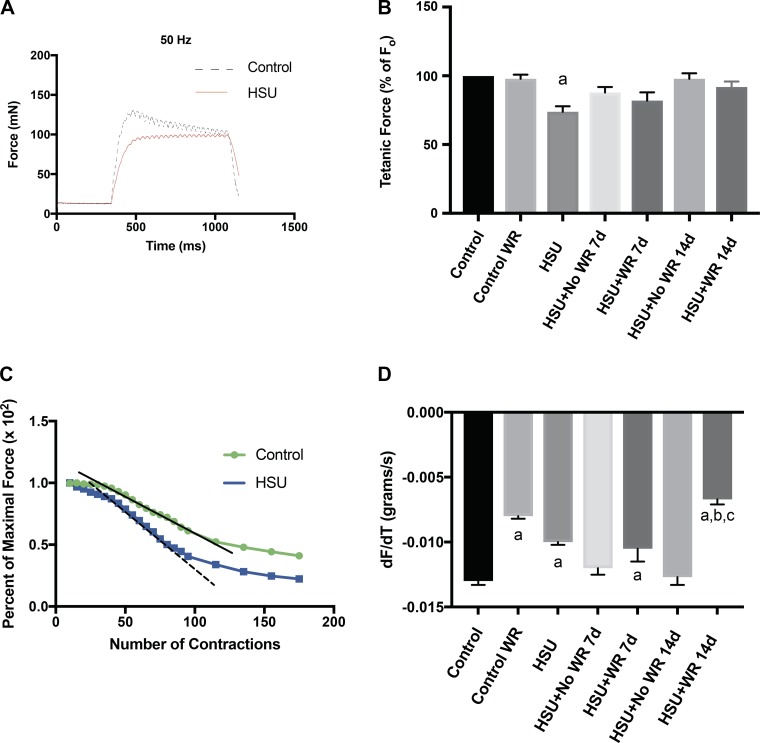

Maximum tetanic force and fatigue were measured in vivo. An example of a tetanic force record taken at 50 Hz before and after 14 days of HSU is shown in Fig. 4A. Maximum force was reported as a percentage of initial tetanic maximum force output that was obtained at 100 Hz (Fig. 4B). Maximum force decreased by 27% after 2 wk of HSU relative to the control force record, but there was no statistically significant difference between control and recovery measurements. An example of two fatigue curves for one animal is shown in Fig. 4C; the linear portion of each normalized force curve along the fatigue protocol is shown with a corresponding line. The slope of each fatigue curve was also calculated as the rate of absolute fatigue (Fig. 4D). The ControlWR group had a 32% lower rate of fatigue (slope) after 14 days of wheel running compared with slope of the control curves, showing that exercise induced an expected improvement in fatigue resistance. Interestingly, the HSU group also had a significantly lower rate of fatigue (20%, P < 0.05) compared with the cage control animals, but this was likely reflected by the lower absolute starting maximal force after HSU compared with the control muscle. The maximal plantarflexor force from the HSU+NoWR group returned to pre-HSU rates by 7 days of recovery from HSU and did not change through 14 days of recovery after HSU. The slope of the fatigue response was unchanged in the HSU+WR group after the first 7 days of reloading, but fatigue resistance improved compared with the HSU+NoWR group by D14. The data in Fig. 4D show that greater improvement in fatigue resistance after HSU was obtained by wheel running compared with no wheel running.

Fig. 4.

Maximum tetanic force and fatigue rate. A: example of tetanic force record from mouse before (control) and after 14 days of hindlimb suspension (HSU). B: tetanic force presented as % of initial tetanic maximum force output (Fo) for each experimental condition (n = 6). C: example of a force record from 1 mouse before (Control) and after 14 days of HSU. The slope of the linear portion of the fatigue curve is shown for control (black solid line) and HSU (black dashed line). D: fatigue presented as the rate of change (slope) of loss of force along the linear portion of the fatigue curve and obtained as shown in C. Data in B and D (n = 6/group) are presented as means ± SE. aP ≤ 0.05 vs. Control; bP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU; cP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU+NoWR. Statistical analysis was performed by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test.

Myosin heavy chain composition, fiber type frequency, and cross-sectional area.

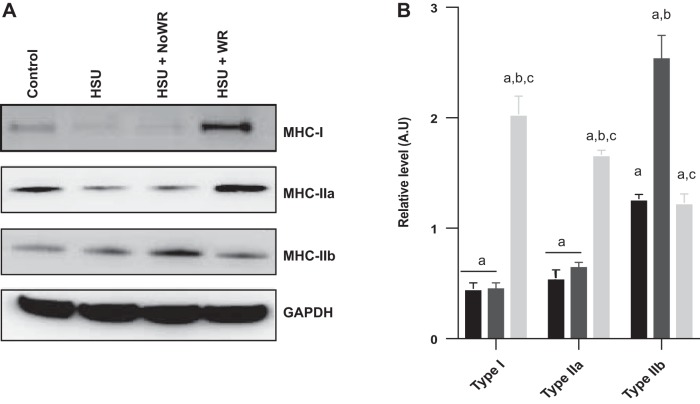

HSU has been reported to cause oxidative-to-glycolytic fiber type switching as well as targeted atrophy of oxidative fibers (18). These effects were evaluated through Western blot analysis (Fig. 5) and via immunohistochemical staining of MHC (Fig. 6). Western blot analysis showed that type IIa MHC decreased and type IIb MHC increased after HSU. The percentage of type I MHC abundance increased and type IIb MHC decreased in reloading conditions in muscles exposed to wheel running. However, the abundance of type I MHC decreased with HSU and did not recover with loading only. MHC IIa protein abundance increased in muscles that underwent wheel running during the reloading period (Fig. 5B). We next examined the change in MHC expression by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 6, A–E). The data suggest that the frequency of type 1 fibers was significantly reduced (−73%) at the end of the second week of recovery in the HSU+NoWR group (Fig. 6F). The type I fiber frequency in the HSU+WR mice recovered to control values by 14 days after HSU. ControlWR mice had significant increases in type IIa fiber frequency (+66%) compared with the Control group at the end of the study. Furthermore, the HSU+WR and ControlWR groups had significantly elevated frequencies of type IIa fibers compared with the HSU group (+95% and +139%, respectively) and the HSU+NoWR group (+60% and +97%, respectively) after 14 days of recovery after HSU. Type IIb/x fiber frequencies were inversely related to type IIa changes. The ControlWR and HSU+WR groups had significantly fewer type IIb/x fibers than Control (−41% and −24%, P < 0.05 respectively), HSU (−54% and −41%, P < 0.05 respectively), and HSU+NoWR (−49% and −38%, respectively) groups after the 14-day recovery period.

Fig. 5.

Myosin heavy chains. A: representative Western blots for type I MHC and type II MHC in gastrocnemius muscles from control (Control), 14 days of hindlimb suspension (HSU), HSU + 14 days of cage control activity (HSU+NoWR), and HSU followed by 14 days of wheel running (HSU+WR). n = 6/group. B: myosin heavy chain data were normalized to the GAPDH signal for that lane and expressed in arbitrary units (AU) for HSU (black bars), HSU+ NoWR (dark gray bars), and HSU+WR (light gray bars). Data are presented as means ± SE. aP ≤ 0.05 vs. Control; bP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU; cP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU+NoWR. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test.

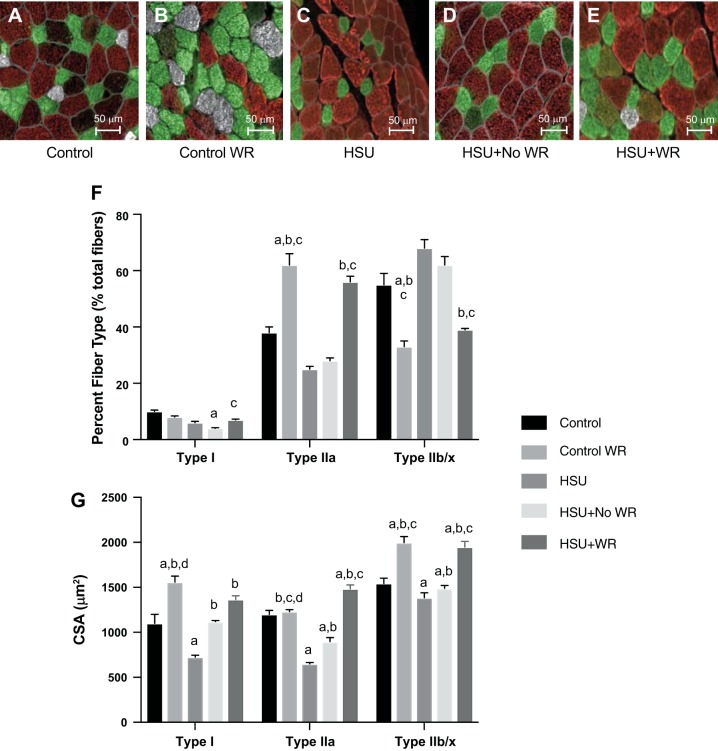

Fig. 6.

Fiber type distribution. A–E: representative images of gastrocnemius muscle cross sections from animals that were cage controls, control animals that were exposed to a wheel and voluntary wheel running (Control/WR), 14 days of hindlimb suspension (HSU), HSU + 14 days of cage control activity (HSU+NoWR), and HSU followed by 14 days of wheel running (HSU+WR) immunohistochemically stained for myosin heavy chain (MHC): MHC type I (white), MHC type IIa (green), MHC type IIb (red), and MHC type IIx (unstained/black). F: quantification of relative fiber frequency. Percentages are expressed as number per muscle; n = 6/group. G: quantification of cross-sectional area (CSA); n = 6/group. Data are presented as means ± SE. aP ≤ 0.05 vs. Control; bP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU; cP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU+NoWR; dP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU+WR. Statistical analysis was performed by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test.

Compared with the Control group, unloading-induced atrophy resulted in a significant decrease of type I (−39%), IIa (−43%), and IIb/x (−21%) fiber CSA (Fig. 6G). Normal ambulation during recovery (HSU+NoWR) significantly improved the CSA in all fiber types, but both IIa and IIb/x fibers remained significantly smaller (P < 0.05) than Control fibers. The wheel running control (ControlWR) group had significantly greater type I (31%, P < 0.05) and IIb/x (23%, P < 0.05) fiber CSA compared with Control mice. Of particular interest is that the HSU mice with 2 wk of voluntary wheel running (HSU+WR) had significantly larger type IIa (43%, P < 0.05) and type IIb/x (34%, P < 0.05) fiber CSA compared with mice that did not have access to wheel running during recovery (HSU+NoWR).

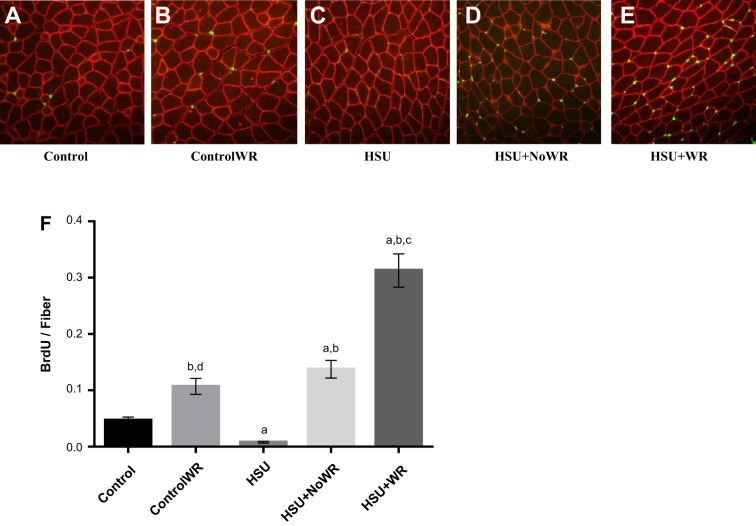

Satellite cells.

Satellite cell proliferation was assessed by measuring BrdU incorporation into myonuclei (Fig. 7). BrdU is a thymidine analog that is used to detect cell proliferation. When activated, satellite cells can proliferate, differentiate, and fuse with existing myofibers, leading to myonuclear accretion (36). Hindlimb suspension decreased cell proliferation, and BrdU incorporation into satellite cells was rarely found. Reloading the muscle after hindlimb suspension significantly increased BrdU levels compared with the Control group (HSU+NoWR: 3-fold increase, P < 0.05; HSU+WR: 6-fold increase, P < 0.05). The HSU+WR group had the greatest incorporation of nuclear BrdU, with sixfold increase (P < 0.05) compared with the Control group and twofold increase (P < 0.05) compared with the HSU+NoWR group.

Fig. 7.

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-labeled nuclei. A–E: representative images of gastrocnemius muscle cross sections. Sections were immunohistochemically stained for BrdU (green) and dystrophin (red). F: quantification of BrdU per fiber. Only BrdU-labeled nuclei that lie fully within the dystrophin border were counted (n = 6/group). Data are presented as means ± SE. aP ≤ 0.05 vs. Control; bP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU; cP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU+NoWR; dP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU+WR. Statistical analysis was performed by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test.

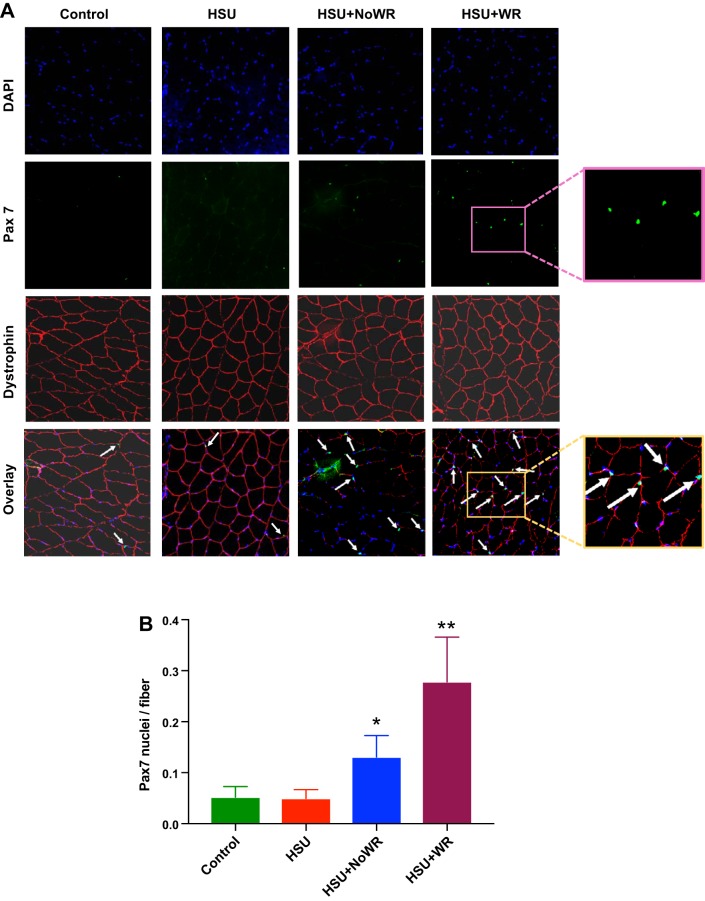

As it is possible that some nuclei that had taken up the BrdU may not have been from myogenic origins, we also examined and quantified Pax 7-positive nuclei in tissue sections because Pax 7 is only found in satellite cells in muscles. Pax 7 is expressed by quiescent and nondifferentiating satellite cells, and for this reason it is an effective marker for satellite cell quantity. Furthermore, Pax 7 is essential for satellite cell function (48). Examples of Pax 7 labeling are shown in Fig. 8A. Quantification of satellite cells (Pax 7-positive nuclei) was obtained per fiber by using the dystrophin boundary to count nuclei inside the fiber. The data show that Pax 7 labeling per fiber was very small in control muscles and after HSU. However, 14 days of reloading after HSU without wheel running increased Pax 7 nuclei per fiber by 94 ± 5% (P < 0.05) in HSU+NoWR muscles compared with control or HSU-only muscles (Fig. 8B). Satellite cell proliferation was further increased by wheel running during the reloading period after HSU because Pax 7 labeling was 4.2-fold greater in HSU+WR compared with control (P < 0.05) or HSU and 120% greater (P < 0.05) in HSU+WR than in HSU+NoWR tissue cross sections (Fig. 8B). These data show that wheel running enhanced total satellite cell proliferation following recovery from HSU.

Fig. 8.

Pax 7 labeling in satellite cells of muscle cross sections. A: representative images of Pax 7-labeled nuclei (green) in gastrocnemius muscle cross sections from muscles of cage control animals that were exposed to a wheel and voluntary wheel running (Control/WR), 14 days of hindlimb suspension (HSU), HSU + 14 days of cage control activity (HSU+NoWR), and HSU followed by 14 d of wheel running (HSU+WR). The fibers were coincubated with anti-dystrophin to identify the fiber boundaries (red) and DAPI (blue) to identify all myonuclei. Arrows indicate examples of Pax7 positive nuclei. Higher magnifications of Pax 7-positive nuclei and the overlay for the same region of Pax 7-positive nuclei are shown on right. B: quantification of relative frequency of Pax 7 nuclei, expressed as Pax 7 nuclei per fiber (n = 6 animals/group). Data are presented as means ± SE. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Control or HSU; **P ≤ 0.05 vs. Control, HSU, or HSU+NoWR.

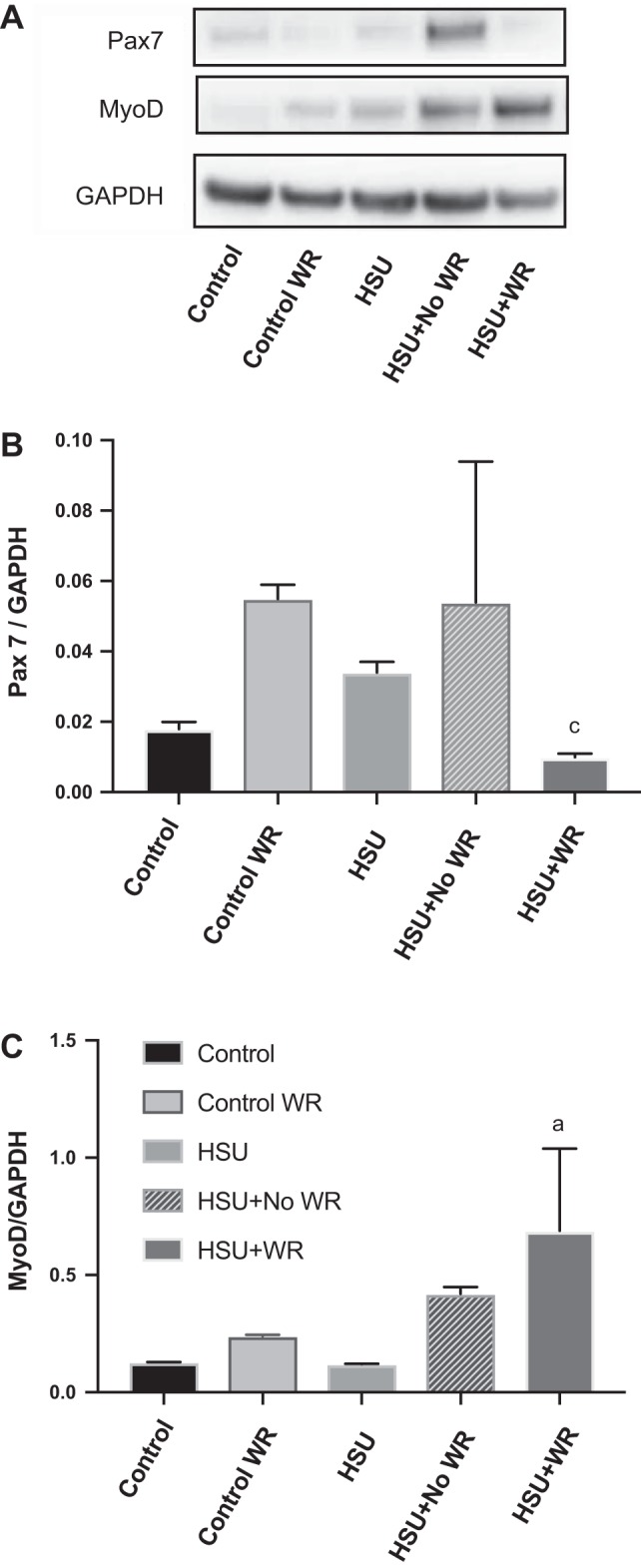

Pax 7 protein abundance (Fig. 9B) and MyoD expression (Fig. 9C) were quantified in muscle homogenates by Western blot analysis. Pax 7 has also been shown to indirectly interfere with MyoD expression (35). Because of the presence of variance in the data, a one-way ANOVA analysis did not detect any significant differences at P ≤ 0.1.

Fig. 9.

MyoD and Pax 7 expression. A: representative image of Western blots for Pax 7, MyoD, and GAPDH. B: for quantification, the Pax 7 expression signal was normalized to signal for GAPDH (n = 6 animals/group). C: quantification of the signal for MyoD protein abundance was normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as means ± SE. aP ≤ 0.1 vs. Control; aP ≤ 0.1 vs. HSU+NoWR. Statistical analysis was performed by 1-way ANOVA with significance at P ≤ 0.1.

Pax 7 protein abundance was unchanged from control levels after HSU and during reloading without the use of running wheels (HSU+NoWR). Although not achieving statistical significance, the ControlWR mice increased Pax 7 expression (2-fold) in muscles from animals exposed to wheel running compared with controls, corresponding with previous studies that found wheel running increases satellite cell proliferation (29). The HSU+WR group had significantly lower (P < 0.05) expression of Pax 7 than the HSU+NoWR group, which might represent that fibers in HSU+WR muscles were further along in the differentiation process than HSU+NoWR.

The protein abundance of MyoD was significantly greater in the HSU+WR (12-fold increase from Control) group after 14 days of recovery (Fig. 9). MyoD protein abundance was significantly greater in the HSU+WR as compared with the HSU+NoWR muscles. Furthermore, the ratio of MyoD to Pax 7 protein abundance was greater in HSU+WR vs. the other groups.

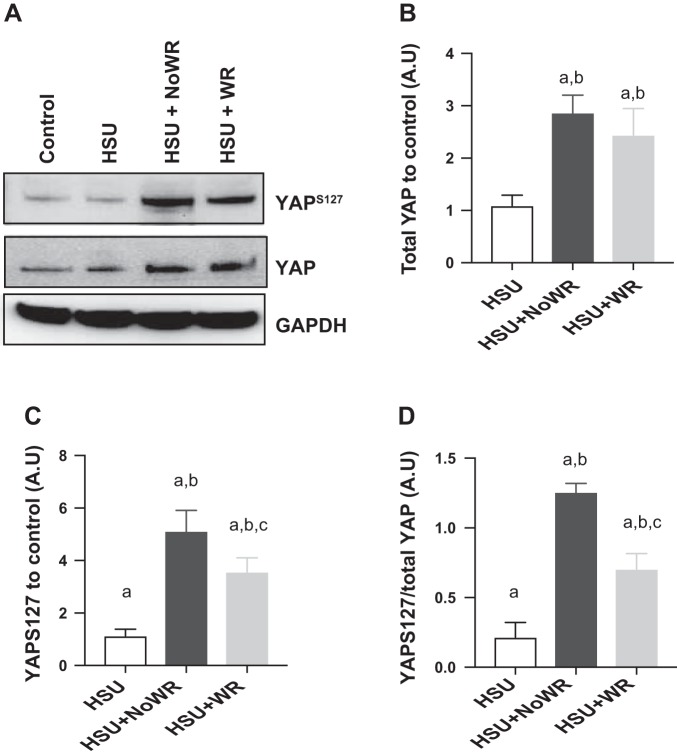

Hippo and YAP signaling.

Total YAP protein abundance was significantly lower in atrophied muscles after HSU but increased with reloading. Both reloading with and without wheel running elevated total YAP to significantly greater levels than HSU (Fig. 10). The protein abundance of YAP phosphorylated at Ser127 was significantly higher in reloaded muscles compared with HSU muscles (Fig. 10), although wheel running suppressed YAP phosphorylation.

Fig. 10.

YAP signaling in gastrocnemius muscles. A: representative Western blots are shown for total YAP and phosphorylated YAP. B: total YAP normalized to control level. C: YAP phosphorylated at Ser127 protein abundance normalized to control level. D: phosphorylation levels of YAP at Ser127 normalized to total YAP protein abundance in reloaded muscles. Data are presented as means ± SE. aP ≤ 0.05 vs. Control; bP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU; cP ≤ 0.05 vs. HSU+NoWR. Statistical analysis was performed by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated whether wheel running after muscle disuse would increase satellite cell activation and improve muscle recovery from reduced gravitational loading. Although treadmill training was shown to improve muscle function after unloading in rats, it also induced significant muscle injury (28). In contrast, voluntary wheel running appeared to improve muscle performance after hindlimb unloading to a level that was not different from nonsuspended mice that had access to voluntary wheel running for 7 days, but it was not known whether the exercise intervention increased satellite cell abundance (22). The results of the present study suggest that voluntary wheel running increased satellite cell proliferation during recovery following HSU and this was associated with improved recovery and lower YAP phosphorylation levels than no wheel running after forced disuse. In contrast, satellite cell proliferation as indicated by BrdU incorporation and Pax 7 labeling was not increased to the same extent as during passive recovery (HSU+NoWR), and this was associated with attenuated recovery after HSU compared with wheel running (HSU+WR).

Voluntary wheel running minimized damage to atrophied muscles.

A challenge during rehabilitation is to optimize strategies that elevate muscle recovery but minimize muscle injury. After HSU, mice ran less (P = 0.13) for the first 3 days of recovery than non-HSU mice (Fig. 2) and then ran distances similar to control mice. This suggests that mice initially self-regulated their activity levels, perhaps to avoid muscle damage. In contrast, forced exercise (e.g., treadmill running) may have induced muscle damage to slow recovery after HSU (28). Thus, there is no indication that there was widespread injury from wheel running, as this would have decreased the activity levels of the mice.

Voluntary wheel running improved fatigue resistance.

An important finding from the present study is that wheel running improved fatigue resistance and type I MHC content in hindlimb muscles in mice during recovery from HSU. It was recently reported that in situ fatigue resistance of the soleus muscle worsens after HSU for at least 15 days, before eventually fully recovering fatigability by 60 days of recovery via normal ambulation after HSU (18). In contrast, our results show that access to wheel running during improves fatigue resistance after 7 days of recovery, which is consistent with other published data (22), and continues to improve fatigue resistance through the 14 measured days of recovery, representing a significant improvement as compared with no wheel running after HSU.

A novel finding of our study was that wheel running during reloading improved the oxidative phenotype of the gastrocnemius muscle, providing a likely mechanism to explain the enhanced resistance to fatigue and perhaps improved muscle recovery as a result of lower death signaling during the reloading period (4). Compared with HSU+NoWR mice, the abundance of type I and IIa MHC and the percentage of type I and IIa fibers in HSU+WR mice were significantly increased while the percentage of type IIb/x fibers and type IIb MHC content decreased, favoring a fiber type shift of the muscle profile from a glycolytic to more of an oxidative phenotype (Fig. 5). Furthermore, type IIa and IIb/x fibers had significantly larger CSAs, providing additional evidence of the efficacy of voluntary wheel running as an effective rehabilitative treatment for muscle disuse (Fig. 6).

Voluntary wheel running activated satellite cells and induced functional and morphological adaptations.

Satellite cells are known to be essential for recovery from injury (16, 53), but their role in normal ambulatory reloading after HSU has been challenged (26). While it is possible that satellite cells are not required for muscle adaptation, it is equally possible that increasing satellite cell activity could modulate and improve muscle remodeling after HSU. An important finding of this study is that voluntary wheel running during reloading provided a sufficient stimulus to activate satellite cells and this was associated with improved muscle remodeling and function after HSU. This is supported by a significant increase in BrdU-positive (Fig. 7) and Pax 7-positive (Fig. 8) nuclei along with greater protein abundance of Pax 7 in homogenates (Fig. 9) of muscles from mice exposed to HSU followed by voluntary wheel running. In the non-wheel running reloaded group, there was a modest increase in the number of BrdU-positive nuclei, coupled with more Pax 7-positive nuclei and greater Pax 7 protein abundance, which are consistent with increased proliferation of satellite cells. However, there was also a tendency for greater MyoD protein abundance in the muscles from the HSU+WR group, which would be expected to be associated with a decline in Pax 7 levels, and therefore satellite cell activation based on Pax 7 protein abundance measured after 14 days of reloading may have underestimated Pax 7 labeling over the initial reloading period. Although it has been reported that ablation of satellite cells did not reduce the initial recovery of muscle mass after HSU (26), it is still possible that the secondary adaptation in muscle recovery that begins at ~14 days of reloading (18) could be regulated, at least in part, by satellite cells. This is supported by observations that satellite cells are sensitive to loading, because 14 days of reloading after HSU increases satellite cell activation in young and old rodents (1, 4–6). While satellite cells did not show marked proliferation during passive recovery (no wheel running), manipulating their activation through low-impact exercise appeared to enhance morphological recovery and improve muscle function. Furthermore, proliferation of satellite cells occurs during the earliest phases of HSU (47), presumably in a failed attempt to initiate programming to improve muscle mass and reduce muscle wasting. The possibility that satellite cell activation regulates muscle remodeling that occurs at later periods of reloading warrants further investigation.

YAP is a transcriptional coregulator that is typically found in areas that have a high densities of progenitor cells (37), presumably as a means to control their activity (32). YAP binds primarily to enhancer elements and regulates stem cell function via mechanical signaling. This also appears to be the case in skeletal muscle, where YAP is elevated during satellite cell proliferation (27). YAP is regulated as part of the Hippo signaling cascade, where localization and binding to TEAD in the nucleus increase cell proliferation (reviewed in Ref. 36), whereas the upstream kinases and MST2 trigger phosphorylation at Ser127 and activation of the kinases LATS1 and LATS2, which in turn phosphorylates YAP at Ser381 (55) and inactivates it by inducing a cytoplasmic localization and proteolysis of YAP (reviewed in Ref. 36). We anticipated that if YAP played a role in regulation of satellite cell proliferation after muscle unloading, the increased mechanical signaling in reloaded muscle as a result of the wheel running should activate YAP and decrease its phosphorylation more than reloading without wheel running.

The data show that YAP protein abundance was similar in control and HSU conditions (Fig. 10A) but compared with control conditions, reloading increased both total YAP (Fig. 10B) and phosphorylation levels of YAP at Ser127 (Fig. 10C), which is phosphorylated by LATS1. Although total YAP was upregulated by reloading after HSU, total phosphorylated YAP at Ser127 was also upregulated even further by reloading after HSU. As phosphorylation relocates YAP to the cytoplasm, where it is inactivated, the lower YAPSer127 to total YAP in the wheel running group suggests an increased removal of the desuppression of YAP to result in a greater relative level of activated YAP by wheel running. Together, these data support the hypothesis that wheel running increases Hippo signaling via YAP activation, and this is consistent with increased satellite cell activation in conditions of reloading after HSU and wheel running. Future studies will be needed to determine whether YAP signaling is essential for wheel running-induced signaling of satellite cell proliferation or if other cofactors such as TAZ can replace YAP in this pathway.

Our data show that nuclear accrual occurred along with a glycolytic-to-oxidative fiber type shift and a corresponding transition in MHCs. This is consistent with other reports that established a relationship between myonuclear content and fiber type profile (42, 47). However, it has also been found that type IIa fiber frequency can increase after 8 wk of voluntary wheel running in satellite cell-depleted mice, although the depletion of satellite cells resulted in less distance run, slower velocities, impaired gait, and decreased grip strength (25). Thus, satellite cells have some role in modulation of adaptations to loading and unloading, and this warrants further investigation. In the present study, satellite cells may have a role in regulating hypertrophic adaptations after unloading, because fiber area of the HSU+WR group was greater after HSU compared with ControlWR animals. Hindlimb-suspended mice also appeared to have a compensatory adaptation during reloading, because HSU mice had a tendency to run 26% further (P = 0.054) and showed greater fatigue resistance than the nonsuspended mice during the second week of wheel running (Fig. 4B).

Conclusions.

This study showed that voluntary wheel running effectively improved the recovery of muscle function and morphology after HSU. Additionally, the study provided evidence that satellite cells have a role in initial reloading, but they may require an underlying “priming” stimulus such as that provided by exercise to be activated. The results provide a rationale for conducting further studies that manipulate satellite cell activation as a therapeutic treatment for muscle disuse atrophy. Future investigation will be necessary to establish the importance of Hippo/YAP signaling and satellite cells in wheel running-induced recovery of muscle force, fatigability, and mass after HSU.

Limitations.

While we utilized wheel running as a tool that would avoid causing unnecessary injury while retaining the benefits of exercise, we cannot fully rule out the possibility that wheel running did cause some minor damage to muscle fibers or their membranes, as injury would have activated satellite cells.

GRANTS

This project has been funded by grants from the West Virginia Stroke Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (CoBRE) P20 GM-109098 to J. S. Mohamed and the West Virginia Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (PSCoR) to S. E. Alway. Additional funding was provided to S. E. Alway by the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.J.B., J.S.M., and S.E.A. conceived and designed research; M.J.B., A.H., and J.S.M. performed experiments; M.J.B., A.H., J.S.M., and S.E.A. analyzed data; M.J.B., J.S.M., and S.E.A. interpreted results of experiments; M.J.B., A.H., J.S.M., and S.E.A. prepared figures; M.J.B. and S.E.A. drafted manuscript; M.J.B. and S.E.A. edited and revised manuscript; M.J.B., A.H., J.S.M., and S.E.A. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Pax 7 antibody was developed by Dr. A. Kawakami, the MANDYS8(8H11) antibody was developed by Dr. G. E. Morris, and the antibodies BA-D5, SC-71, and BF-F3 were developed by Dr. S. Schiaffino. These antibodies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the Department of Biology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA. We also acknowledge the West Virginia University Microscope Imaging Facility, which is supported by the Mary Babb Randolph Cancer Center and National Center for Research Resources Grants P20 RR-016440, P30 RR-032138/GM-103488, and P20 RR-016477.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alway SE, Bennett BT, Wilson JC, Edens NK, Pereira SL. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate improves plantaris muscle recovery after disuse in aged rats. Exp Gerontol 50: 82–94, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alway SE, Bennett BT, Wilson JC, Sperringer J, Mohamed JS, Edens NK, Pereira SL. Green tea extract attenuates muscle loss and improves muscle function during disuse, but fails to improve muscle recovery following unloading in aged rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 118: 319–330, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00674.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alway SE, Degens H, Lowe DA, Krishnamurthy G. Increased myogenic repressor Id mRNA and protein levels in hindlimb muscles of aged rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R411–R422, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00332.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alway SE, Mohamed JS, Myers MJ. Mitochondria initiate and regulate sarcopenia. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 45: 58–69, 2017. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alway SE, Morissette MR, Siu PM. Aging and apoptosis in muscle. In: Handbook of the Biology of Aging (7th ed.), edited by Masoro E, Austad S. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2011, p. 63–118. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alway SE, Myers MJ, Mohamed JS. Regulation of satellite cell function in sarcopenia. Front Aging Neurosci 6: 246, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alway SE, Pereira SL, Edens NK, Hao Y, Bennett BT. β-Hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB) enhances the proliferation of satellite cells in fast muscles of aged rats during recovery from disuse atrophy. Exp Gerontol 48: 973–984, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appell HJ. Skeletal muscle atrophy during immobilization. Int J Sports Med 7: 1–5, 1986. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appell HJ, Forsberg S, Hollmann W. Satellite cell activation in human skeletal muscle after training: evidence for muscle fiber neoformation. Int J Sports Med 9: 297–299, 1988. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1025026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett BT, Mohamed JS, Alway SE. Effects of resveratrol on the recovery of muscle mass following disuse in the plantaris muscle of aged rats. PLoS One 8: e83518, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodine SC. Disuse-induced muscle wasting. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45: 2200–2208, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke RE, Levine DN, Tsairis P, Zajac FE 3rd. Physiological types and histochemical profiles in motor units of the cat gastrocnemius. J Physiol 234: 723–748, 1973. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannavino J, Brocca L, Sandri M, Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA. PGC1-α over-expression prevents metabolic alterations and soleus muscle atrophy in hindlimb unloaded mice. J Physiol 592: 4575–4589, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.275545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannavino J, Brocca L, Sandri M, Grassi B, Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA. The role of alterations in mitochondrial dynamics and PGC-1α over-expression in fast muscle atrophy following hindlimb unloading. J Physiol 593: 1981–1995, 2015. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.286740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darr KC, Schultz E. Hindlimb suspension suppresses muscle growth and satellite cell proliferation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 67: 1827–1834, 1989. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.5.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumont NA, Bentzinger CF, Sincennes MC, Rudnicki MA. Satellite cells and skeletal muscle regeneration. Compr Physiol 5: 1027–1059, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egawa T, Goto A, Ohno Y, Yokoyama S, Ikuta A, Suzuki M, Sugiura T, Ohira Y, Yoshioka T, Hayashi T, Goto K. Involvement of AMPK in regulating slow-twitch muscle atrophy during hindlimb unloading in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 309: E651–E662, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00165.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng HZ, Chen X, Malek MH, Jin JP. Slow recovery of the impaired fatigue resistance in postunloading mouse soleus muscle corresponding to decreased mitochondrial function and a compensatory increase in type I slow fibers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 310: C27–C40, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00173.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer M, Rikeit P, Knaus P, Coirault C. YAP-mediated mechanotransduction in skeletal muscle. Front Physiol 7: 41, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flück M, Hoppeler H. Molecular basis of skeletal muscle plasticity—from gene to form and function. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 146: 159–216, 2003. doi: 10.1007/s10254-002-0004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guderley H, Joanisse DR, Mokas S, Bilodeau GM, Garland T Jr. Altered fibre types in gastrocnemius muscle of high wheel-running selected mice with mini-muscle phenotypes. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 149: 490–500, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanson AM, Stodieck LS, Cannon CM, Simske SJ, Ferguson VL. Seven days of muscle re-loading and voluntary wheel running following hindlimb suspension in mice restores running performance, muscle morphology and metrics of fatigue but not muscle strength. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 31: 141–153, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s10974-010-9218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao Y, Jackson JR, Wang Y, Edens N, Pereira SL, Alway SE. β-Hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate reduces myonuclear apoptosis during recovery from hind limb suspension-induced muscle fiber atrophy in aged rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R701–R715, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00840.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irintchev A, Wernig A. Muscle damage and repair in voluntarily running mice: strain and muscle differences. Cell Tissue Res 249: 509–521, 1987. doi: 10.1007/BF00217322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson JR, Kirby TJ, Fry CS, Cooper RL, McCarthy JJ, Peterson CA, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Reduced voluntary running performance is associated with impaired coordination as a result of muscle satellite cell depletion in adult mice. Skelet Muscle 5: 41, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13395-015-0065-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson JR, Mula J, Kirby TJ, Fry CS, Lee JD, Ubele MF, Campbell KS, McCarthy JJ, Peterson CA, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Satellite cell depletion does not inhibit adult skeletal muscle regrowth following unloading-induced atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C854–C861, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00207.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Judson RN, Tremblay AM, Knopp P, White RB, Urcia R, De Bari C, Zammit PS, Camargo FD, Wackerhage H. The Hippo pathway member Yap plays a key role in influencing fate decisions in muscle satellite cells. J Cell Sci 125: 6009–6019, 2012. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasper CE, White TP, Maxwell LC. Running during recovery from hindlimb suspension induces transient muscle injury. J Appl Physiol (1985) 68: 533–539, 1990. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurosaka M, Naito H, Ogura Y, Kojima A, Goto K, Katamoto S. Effects of voluntary wheel running on satellite cells in the rat plantaris muscle. J Sports Sci Med 8: 51–57, 2009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeBlanc A, Rowe R, Schneider V, Evans H, Hedrick T. Regional muscle loss after short duration spaceflight. Aviat Space Environ Med 66: 1151–1154, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li P, Akimoto T, Zhang M, Williams RS, Yan Z. Resident stem cells are not required for exercise-induced fiber-type switching and angiogenesis but are necessary for activity-dependent muscle growth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C1461–C1468, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00532.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lian I, Kim J, Okazawa H, Zhao J, Zhao B, Yu J, Chinnaiyan A, Israel MA, Goldstein LS, Abujarour R, Ding S, Guan KL. The role of YAP transcription coactivator in regulating stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev 24: 1106–1118, 2010. doi: 10.1101/gad.1903310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell PO, Pavlath GK. A muscle precursor cell-dependent pathway contributes to muscle growth after atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1706–C1715, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.5.C1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohira Y, Jiang B, Roy RR, Oganov V, Ilyina-Kakueva E, Marini JF, Edgerton VR. Rat soleus muscle fiber responses to 14 days of spaceflight and hindlimb suspension. J Appl Physiol (1985) 73, Suppl: 51S–57S, 1992. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.2.S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olguin HC, Olwin BB. Pax-7 up-regulation inhibits myogenesis and cell cycle progression in satellite cells: a potential mechanism for self-renewal. Dev Biol 275: 375–388, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panciera T, Azzolin L, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. Mechanobiology of YAP and TAZ in physiology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18: 758–770, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panciera T, Azzolin L, Fujimura A, Di Biagio D, Frasson C, Bresolin S, Soligo S, Basso G, Bicciato S, Rosato A, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. Induction of expandable tissue-specific stem/progenitor cells through transient expression of YAP/TAZ. Cell Stem Cell 19: 725–737, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pellegrino MA, Desaphy JF, Brocca L, Pierno S, Camerino DC, Bottinelli R. Redox homeostasis, oxidative stress and disuse muscle atrophy. J Physiol 589: 2147–2160, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.203232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pistilli EE, Siu PM, Alway SE. Interleukin-15 responses to aging and unloading-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C1298–C1304, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00496.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powers SK, Smuder AJ, Judge AR. Oxidative stress and disuse muscle atrophy: cause or consequence? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 15: 240–245, 2012. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328352b4c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prisby RD, Nelson AG, Latsch E. Eccentric exercise prior to hindlimb unloading attenuated reloading muscle damage in rats. Aviat Space Environ Med 75: 941–946, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Putman CT, Sultan KR, Wassmer T, Bamford JA, Skorjanc D, Pette D. Fiber-type transitions and satellite cell activation in low-frequency-stimulated muscles of young and aging rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56: B510–B519, 2001. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.12.B510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reid MB, Moylan JS. Beyond atrophy: redox mechanisms of muscle dysfunction in chronic inflammatory disease. J Physiol 589: 2171–2179, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.203356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rittweger J, Frost HM, Schiessl H, Ohshima H, Alkner B, Tesch P, Felsenberg D. Muscle atrophy and bone loss after 90 days’ bed rest and the effects of flywheel resistive exercise and pamidronate: results from the LTBR study. Bone 36: 1019–1029, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryan MJ, Jackson JR, Hao Y, Leonard SS, Alway SE. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase reduces oxidative stress and improves skeletal muscle function in response to electrically stimulated isometric contractions in aged mice. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 38–52, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan MJ, Jackson JR, Hao Y, Williamson CL, Dabkowski ER, Hollander JM, Alway SE. Suppression of oxidative stress by resveratrol after isometric contractions in gastrocnemius muscles of aged mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65: 815–831, 2010. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schultz E, Darr KC, Macius A. Acute effects of hindlimb unweighting on satellite cells of growing skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 76: 266–270, 1994. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seale P, Ishibashi J, Scimè A, Rudnicki MA. Pax7 is necessary and sufficient for the myogenic specification of CD45+:Sca1+ stem cells from injured muscle. PLoS Biol 2: E130, 2004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siu PM, Pistilli EE, Butler DC, Alway SE. Aging influences cellular and molecular responses of apoptosis to skeletal muscle unloading. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C338–C349, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00239.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siu PM, Pistilli EE, Murlasits Z, Alway SE. Hindlimb unloading increases muscle content of cytosolic but not nuclear Id2 and p53 proteins in young adult and aged rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 100: 907–916, 2006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stelzer JE, Widrick JJ. Effect of hindlimb suspension on the functional properties of slow and fast soleus fibers from three strains of mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 95: 2425–2433, 2003. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01091.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi H, Suzuki Y, Mohamed JS, Gotoh T, Pereira SL, Alway SE. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate increases autophagy signaling in resting and unloaded plantaris muscles but selectively suppresses autophagy protein abundance in reloaded muscles of aged rats. Exp Gerontol 92: 56–66, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.02.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang YX, Rudnicki MA. Satellite cells, the engines of muscle repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 127–133, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nrm3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Widrick JJ, Maddalozzo GF, Hu H, Herron JC, Iwaniec UT, Turner RT. Detrimental effects of reloading recovery on force, shortening velocity, and power of soleus muscles from hindlimb-unloaded rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1585–R1592, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00045.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao B, Li L, Tumaneng K, Wang CY, Guan KL. A coordinated phosphorylation by Lats and CK1 regulates YAP stability through SCF(beta-TRCP). Genes Dev 24: 72–85, 2010. doi: 10.1101/gad.1843810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]