Abstract

The IL-6 cytokine family activates intracellular signaling pathways through glycoprotein-130 (gp130), and this signaling has established regulatory roles in muscle glucose metabolism and proteostasis. Although the IL-6 family has been implicated as myokines regulating the muscles’ metabolic response to exercise, gp130’s role in mitochondrial quality control involving fission, fusion, mitophagy, and biogenesis is not well understood. Therefore, we examined gp130’s role in basal and exercise-trained muscle mitochondrial quality control. Muscles from C57BL/6, skeletal muscle-specific gp130 knockout (KO) mice, and C2C12 myotubes, were examined. KO did not alter treadmill run-to-fatigue or indices of mitochondrial content [cytochrome-c oxidase (COX) activity] or biogenesis (AMPK, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α, mitochondrial transcription factor A, and COX IV). KO increased mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS-1) while suppressing mitofusin-1 (MFN-1), which was recapitulated in myotubes after gp130 knockdown. KO induced ubiquitin-binding protein p62, Parkin, and ubiquitin in isolated mitochondria from gastrocnemius muscles. Knockdown of gp130 in myotubes suppressed STAT3 and induced accumulation of microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3B (LC3)-II relative to LC3-I. Suppression of myotube STAT3 did not alter FIS-1 or MFN-1. Exercise training increased muscle gp130 and suppressed STAT3. KO did not alter the exercise-training induction of COX activity, biogenesis, FIS-1, or Beclin-1. KO increased MFN-1 and suppressed 4-hydroxynonenal after exercise training. These findings suggest a role for gp130 in the modulation of mitochondrial dynamics and autophagic processes.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Although the IL-6 family of cytokines has been implicated in the regulation of skeletal muscle protein turnover and metabolism, less is understood about its role in mitochondrial quality control. We examined the glycoprotein-130 receptor in the regulation of skeletal muscle mitochondria quality control in the basal and exercise-trained states. We report that the muscle glycoprotein-130 receptor modulates basal mitochondrial dynamics and autophagic processes and is not necessary for exercise-training mitochondrial adaptations to quality control.

Keywords: endurance training, IL-6, mitochondria, STAT3

INTRODUCTION

The interleukin-6 (IL-6) cytokine family has been widely investigated for its role in the regulation of muscle remodeling, growth, and metabolism (54, 63, 67). The IL-6 family initiates cellular signaling through interactions with specific cytokine receptors and glycoprotein-130 (gp130; 13). Although several intracellular pathways can be activated by gp130 signaling, STAT3 activation is often regarded as the canonical pathway (13). Plasma IL-6 has been associated with muscle oxidative metabolism alterations that occur with disease and exercise (17, 65). Chronically elevated plasma IL-6 in tumor-bearing mice can negatively regulate muscle mass and oxidative metabolism (3, 65). Alternatively, exercise-induced increases in plasma IL-6 have been implicated in the acute metabolic response to exercise (17), and contracting muscles are a major producer of IL-6 (14, 15). Although exercise can alter systemic and local intracellular signaling that regulates muscle metabolic homeostasis (11, 22, 48, 70), our understanding of the importance of IL-6 signaling for exercise-induced mitochondrial adaptations has proven to be challenging. A role for IL-6 and muscle STAT3 in the regulation of lipid, glucose, and oxidative metabolism during exercise has been previously established (9, 30, 44, 65, 69). However, the direct involvement of muscle gp130 in IL-6 signaling’s mediation of skeletal muscle mitochondrial quality control has yet to be determined.

Mitochondrial quality control includes several processes, such as mitochondrial biogenesis, dynamics, and autophagy/mitophagy (57). These processes are critical for allowing mitochondria to perform essential functions that impact skeletal muscle metabolic health (6, 70). Mitochondrial biogenesis plays an important role in metabolic health and plasticity (23, 24). Acutely, exercise increases mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) by the activating adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK; 12, 70). The mitochondrial remodeling process known as “dynamics” occurs via constant fission and fusion of mitochondria in response to metabolic stressors (11, 12). Various stimuli, including exercise and IL-6, have been demonstrated to regulate the coordinated process of mitochondrial fission and fusion (10, 26, 27). Mitochondrial dynamics are regulated by the expression and function of mitofusion proteins MFN-1 and MFN2 and fission proteins mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS-1) and dynamin-related protein-1 (DRP-1; 50, 61). Altered fission and fusion are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, which can alter the acute metabolic response to exercise training (10, 25). Another critical aspect of mitochondrial quality control is the removal of dysfunctional and damaged mitochondria through autophagy, termed “mitophagy” (19, 28, 60). This process is critical for maintaining a healthy mitochondrial network (35), and the dysregulation of any of these processes can lead to the accumulation of protein aggregates and dysfunctional organelles and the loss of muscle metabolic homeostasis (34). Thus, coordination between biogenesis, dynamics, and autophagy/mitophagy processes is critical for skeletal muscle metabolic quality and plasticity (5, 26, 34), and further examination of this cellular synchronization through IL-6/gp130 signaling is warranted (28).

Evidence suggests that IL-6 signaling can regulate muscle mitochondrial quality control (8, 65, 66). The collective results from global IL-6 knockout mice have established a role for IL-6 in the acute exercise response (14, 68). Systemic IL-6 knockout mice exhibit normal growth and mitochondrial respiration (42). Additionally, run time to fatigue following an acute bout of exercise is not altered when compared with wild-type controls (42). However, treadmill exercise training-induced improvements to muscle cytochrome-c oxidase (COX) activity and citrate synthase activity were impaired in mice lacking IL-6, suggesting a role for IL-6 signaling in the response of metabolic plasticity to exercise training (68). Consistent with the involvement of IL-6 during exercise, muscle STAT3 signaling is transiently increased by acute exercise (37). Although there is mounting evidence for a regulatory role of systemic IL-6 in the metabolic adaptation to exercise, further mechanistic research is needed to understand the muscle-specific signaling involved. Therefore, we examined the necessity of muscle gp130 signaling and its effects on mitochondrial quality control in basal and exercise-trained states. We used a muscle-specific gp130 knockout mouse, which generates a functional knockout model for all members of the IL-6 family of cytokines, while the endogenous production of these cytokines remains intact. We hypothesized that muscle gp130 receptor loss and downstream STAT3 inhibition would disrupt basal muscle mitochondrial quality control through mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy/mitophagy. We also hypothesized that muscle-specific loss of gp130 would attenuate the treadmill training-induced improvements in skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism. To accomplish this, we examined muscle-specific loss of the gp130 receptor in sedentary and treadmill exercise-trained mice. We also performed additional mechanistic studies that examined downstream gp130 signaling (STAT3) in C2C12 myotubes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male mice on a C57BL/6 background were bred with gp130-floxed mice provided by Dr. Colin Stewart’s laboratory [Laboratory of Cancer and Developmental Biology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Frederick, MD] in collaboration with Dr. Lothar Hennighausen (Laboratory of Genetics and Physiology, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 27) as previously published (45). Male gp130-floxed mice were bred with Cre-expressing mice driven by the myosin light chain (mlccre) promoter from Dr. Steven Burden (New York University, New York, NY) to generate gp130flfl; mlccre/cre mice, which have skeletal muscle deletion of gp130 (hereinafter referred to as KO). Mice containing floxed gp130 but lacking mlccre were used as controls [hereinafter referred to as C57BL/6 (B6)]. Mice were genotyped by PCR using a tail snip taken at weaning to verify the presence or absence of gp130 flox and mlccre (45). Additionally, DNA was isolated from quadriceps, heart, and spleen tissue and amplified using PCR to verify muscle specificity (45). Mice were housed four to five per cage for each genotype in all experiments. All experiments and methods performed were done in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations at the University of South Carolina. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of South Carolina approved all experiments.

Experiments used for this study were conducted separately, and sample sizes were chosen on the basis of expected outcomes from previous studies utilizing the KO mouse (45). For the treadmill exercise we used eighteen 12-wk-old B6 mice (n = 7 cage control, n = 11 exercise training) and twelve 12-wk-old mice with skeletal muscle-specific deletion of gp130 receptor (skm-gp130 KO; n = 5 cage control, n = 7 exercise training). An additional cohort consisting of ten 16-wk-old mice (B6, n = 5; skm-gp130 KO, n = 5) were selected to complete a run-to-fatigue test and to determine muscle function. For the mitochondrial isolation, an additional set of 16-wk-old B6 (n = 6) and skm-gp130 KO mice (n = 6) were euthanized, and mitochondria were isolated from fresh gastrocnemius muscle. For succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) enzyme activity a final cohort of 14-wk-old mice (B6, n = 5; skm-gp130 KO, n = 5) were euthanized, and the tibialis anterior muscle was cryosectioned. A total of 62 male mice were used in this study.

Treadmill exercise protocol.

At 6 wk of age, B6 and KO mice were randomly assigned to either cage control or exercise training. After 3 days of acclimation, which consisted of running at a 5% grade for a total of 20 min with a gradual increase in speed starting at 10 m/min and increasing to 18 m/min, mice began exercise training. The training regimen consisted of 6 days/wk for a total of 6 wk as previously described (2). The individual training sessions consisted of a 5-min warm-up at 10 m/min at 5% grade, followed by 55 min of running at 18 m/min at 5% grade. All mice completed the exercise-training regimen. Mice (12 wk of age) were euthanized 48 h following the last exercise session.

Run-to-fatigue test.

At 16 wk of age, B6 and KO mice were subjected to a run-to-fatigue test. The test began at 5 m/min at 5% grade, and the speed was then increased after 5 min to 10 m/min, followed by 15 m/min after another 5 min. Thirty minutes into the test the speed was adjusted to a maximum of 25 m/min. The maximum time, in seconds, that the mice could run with gentle prods during the entire trial was recorded as the run-to-fatigue time (46). Mice were encouraged to run by gentle prods, as needed. Exercise was conducted at the beginning of the dark cycle (1900).

Muscle function.

At 16 wk of age, B6 and KO mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane inhalation for muscle force analysis in situ. The right distal tibialis anterior tendon was attached to a force transducer (Aurora Scientific, Aurora, ON, Canada) using 5-0 silk sutures. The sciatic nerve was exposed proximal to the knee and subjected to a single stimulus to determine the optimal length-tension relationship (Lo). Once Lo was obtained, a force-frequency curve was generated, and maximal tetanic force was determined (62). Following a 5-min rest period, the fatigability of the tibialis anterior muscle was assessed as previously described with minor modifications (52). The tibialis anterior muscle was subjected to repeated submaximal stimuli, 120 Hz, every second for 3 min followed immediately by repeated maximal stimuli, 250 Hz, every second for 3 min to elicit moderate and severe fatigue, respectively (52, 62).

Tissue collection.

Mice were given a subcutaneous injection of ketamine-xylazine-acepromazine cocktail (1.4 ml/kg body wt), and tissues were dissected, weighed, and then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C as previously described (38).

Quadriceps membrane fractionation.

Approximately 60 mg of quadriceps muscles were homogenized in chilled lysis buffer (10 mmol/l HEPES, 2 mmol/l EDTA, 1 mmol/l MgCl2, 10 mmol/l Na4P2O7, 500 µmol/l Na3VO4, 5 µg/ml leupeptin, 5 µg/ml pepstatin, 5 µg/ml aprotinin, 1 mmol/l DTT, and 1 mmol/l PMSF) with glass-on-glass tissue homogenizer (Kontes Glass, Vineland, NJ). Crude soluble and insoluble fractions were separated by centrifugation (5 min at 1,000 g). The insoluble fraction was discarded, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min at 37,000 g to generate membrane and cytosolic fractions. The membrane pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) and stored at −80°C.

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed using membrane fractions, crude whole muscle homogenates, and isolated mitochondria from quadriceps and gastrocnemius muscle as previously described (20). Briefly, 10–40 µg of protein homogenate were fractionated on 7–15% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes overnight at 4°C. Equal protein loading of the gels was assessed by Ponceau staining, and then membranes were blocked in 5% milk-Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST) for 1–2 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies for COX I–V, FIS-1 (Abnova), gp130 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE; ECM Biosciences), MFN-1, microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3B (LC3)-I and LC3-II, Beclin-1, phospho-STAT3Y705, STAT3, Total OXPHOS Cocktail (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), and GAPDH were incubated at 1:2,000 to 1:10,000 dilutions in 5% milk-TBST for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Secondary anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG-conjugated antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) were incubated with membranes at a 1:2,000 dilution in 5% milk-TBST for 1 h at room temperature. After several washes, enhanced chemiluminescence was used to visualize the antibody-antigen interaction and developed by digital imaging (G-Box; Syngene, Frederick, MD). Immunoblots were analyzed by measuring the integrated optical density of each band using ImageJ imaging software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). For exercise comparisons, common samples were run on two different gels at the same time and exposed for the same duration.

Skeletal muscle-isolated mitochondria.

Mitochondrial isolation from the left gastrocnemius muscle was performed in six B6 and six KO mice following a previously described protocol (4). Briefly, freshly dissected gastrocnemius muscles were minced and digested for 30 min in isolation buffer 1 (2 M Tris·HCl, 1 M KCl, and 0.5 M EDTA/Tris) containing 0.05% trypsin solution. The digested solution was spun at 200 g for 3 min, and the pellet was resuspended and homogenized using a Teflon pestle. The homogenate was spun at 700 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected and spun at 8,000 g for another 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of isolation buffer 1 and spun again at 8,000 g for 10 min. The resulting pellets were gently resuspended in 50 μl of isolation buffer 2 (0.1 M EGTA/Tris and 1 M Tris·HCl) and contained the isolated mitochondrial suspension. The Bradford method was used to determine total mitochondria protein concentration in the purified mitochondrial fraction.

Cytochrome-c oxidase activity.

Cytochrome-c oxidase (COX) activity was assessed in isolated mitochondria and whole muscle homogenates from the gastrocnemius muscle. For whole muscle analysis, gastrocnemius tissues were homogenized in extraction buffer (0.1 M KH2PO4/Na2HPO4 and 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.2). Mitochondria were isolated in buffer as described above. COX enzyme activity was determined by measuring the rate of oxidation of fully reduced cytochrome c at 550 nm as previously described (26).

Tibialis anterior cryosectioning and succinate dehydrogenase enzyme activity.

Serial transverse muscle sections (10 μm) were cut from the midbelly of the tibialis anterior on a cryostat at −20°C and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) enzyme activity was performed as previously described to determine myofiber oxidative capacity (36). Frozen sections were air dried at room temperature for 10 min, followed by incubation in a solution containing 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 0.1 M MgCl2, 0.2 M succinic acid, and 2.4 mM nitroblue tetrazolium at 37°C for 45 min. Sections were then washed in distilled water for 3 min, dehydrated in 50% ethanol for 2 min, and mounted for viewing with mounting media. Digital images were acquired as previously described (36). The percentage of SDH-positive fibers was determined at ×20. The SDH staining intensity was determined by subtracting the background from each slide to create an integrated optical density for each myofiber. The percentages of dark stain (high SDH activity) were quantified and expressed as percentage of total muscle fibers.

C2C12 myotube cell culture.

C2C12 myoblasts (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (45). At >90% confluency, C2C12 myoblasts were incubated in differentiation medium (DMEM supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated horse serum, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin) for 72 h to induce differentiation, and experiments were performed.

Bafilomycin A1 autophagy assay.

Bafilomycin A1 (100 nM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), a lysosomal autophagy inhibitor, was dissolved in DMSO at a working concentration of 100 µM (55). Bafilomycin A1 was then added to culture medium at a concentration of 100 nM for a duration of 3 h (55). Following 3 h, myotubes were collected for protein analysis (53).

STAT3 RNA interference and inhibitors.

C2C12 myotubes were transfected with scramble siRNA (GE Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO), STAT3 siRNA, and gp130 siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) 3 days postdifferentiation using Dharmafect 3 transfection reagent (GE Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, siRNA and transfection reagent were separately diluted in serum-free and antibiotics-free DMEM and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The diluted transfection reagent was then added to the siRNA mixture and allowed to complex with siRNA for 20 min. siRNA-transfection reagent complexes were then added to the antibiotics-free differentiation medium, and myotubes were incubated for 24 h in transfection-containing medium (100 nM siRNA concentration). Transfection efficiency was validated by cotransfecting 20 nM (final concentration) of siGLO RISC-Free Control siRNA (GE Dharmacon). Fluorescence was visualized by Cy3 filter to determine transfection efficiency. Validated transfected myotubes were collected for protein analysis.

Four days postdifferentiation, STAT3 inhibitors C188-9 (10 μM) and LLL12 (100 µM; BioVision, Milpitas, CA) were added to culture medium for a duration of 2 h. Following 2 h, myotubes were collected for Western blot analysis (71). All analysis included six replicates per control and treatment groups.

Statistical analysis.

Results are reported as means ± SE. Analysis was completed using either a standard two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student’s t-test when appropriate. Post hoc analyses were performed with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test when appropriate. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (La Jolla, CA).

Data availability.

All protocols used and data generated from this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

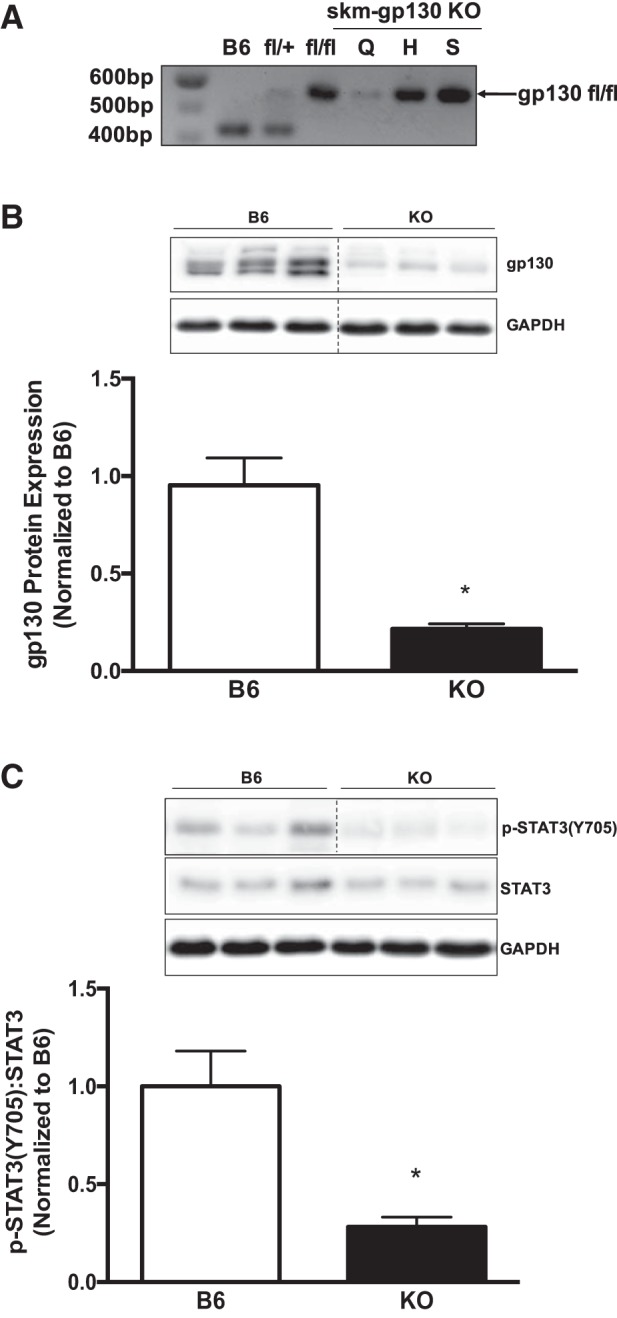

Skeletal muscle-specific loss of gp130.

To confirm skeletal muscle-specific loss of gp130 in KO mice, we isolated DNA from quadriceps, heart, and spleen tissue (Fig. 1A). Our results demonstrate that loss of the gp130 receptor in KO mice was specific to skeletal muscle and did not affect cardiac muscle or spleen tissue. In addition, we assessed the protein expression of gp130 in the membrane fraction of quadriceps muscle and confirmed reduced gp130 protein expression (Fig. 1B). We next addressed whether skeletal muscle gp130 loss would affect basal STAT3 phosphorylation, a downstream target of gp130. We observed a significant reduction of STAT3 phosphorylation in the quadriceps muscle of KO mice compared with B6 mice (Fig. 1C). Additionally, there was no alteration in IL-6 mRNA expression in the gastrocnemius of KO mice compared with B6 (data not shown). Thus, we demonstrate effective knockdown of gp130 and downstream signaling in mature muscle fibers.

Fig. 1.

Muscle glycoprotein-130 (gp130) knockout (KO) characterization. To validate our treatment, we examined multiple tissues for DNA and the gastrocnemius for protein analysis in our KO animal. A: representative DNA gel of floxed (fl) and wild-type gp130 PCR product from quadriceps (Q), heart (H), and spleen (S) tissues of mice with skeletal muscle-specific deletion of gp130 receptor (skm-gp130 KO). B, top: representative immunoblot of membrane gp130 protein expression in C57BL/6 (B6) and KO mice. Bottom: quantification of membrane gp130 protein expression. Dashed lines indicate that blot was cropped for representative purposes. C, top: representative immunoblots of phospho (p)-STAT3Y705, total STAT3, and GAPDH in B6 and KO mice. Bottom: quantification of p-STAT3Y705 and total STAT3 in B6 and KO mice. Total n = 7 B6 mice and 5 KO mice. All values are reported as means ± SE. All values were normalized to B6. Analyses were conducted using unpaired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. *Statistically different from B6.

Effect of gp130 loss and exercise on body weight, food intake, gastrocnemius mass, and tibia length.

To examine whether KO mice have phenotypical characteristics similar to those of B6 mice, we assessed body weight, food intake, gastrocnemius mass, and tibia length. In accordance with previous reports from our group (45), KO and B6 mice had similar body weight, gastrocnemius mass, and tibia length for either genotype or exercise treatment (Table 1). In addition, there was a main effect of exercise training to increase daily food intake regardless of skeletal muscle gp130 loss. These results demonstrate that neither skeletal muscle gp130 loss nor exercise training affected body weight, muscle mass, or tibia length.

Table 1.

Effect of glycoprotein-130 and exercise on body weight, gastrocnemius mass, food intake, and tibia length

| C57BL/6 |

KO |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cage Control | Exercise Trained | Cage Control | Exercise Trained | |

| n | 7 | 11 | 5 | 7 |

| Body weight, g | 25 ± 0.5 | 25 ± 0.7 | 24 ± 1.1 | 23 ± 0.8 |

| Gastrocnemius mass, mg | 126 ± 3.0 | 125 ± 2.0 | 128 ± 3.0 | 125 ± 4.0 |

| Food intake, g/day | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.8* | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 5.2 ± 0.6* |

| Tibia length, mm | 17 ± 0.1 | 17 ± 0.2 | 17 ± 0.1 | 17 ± 0.1 |

Values are means ± SE. KO, skeletal muscle-specific knockout of glycoprotein-130.

Main effect of exercise, P = 0.005.

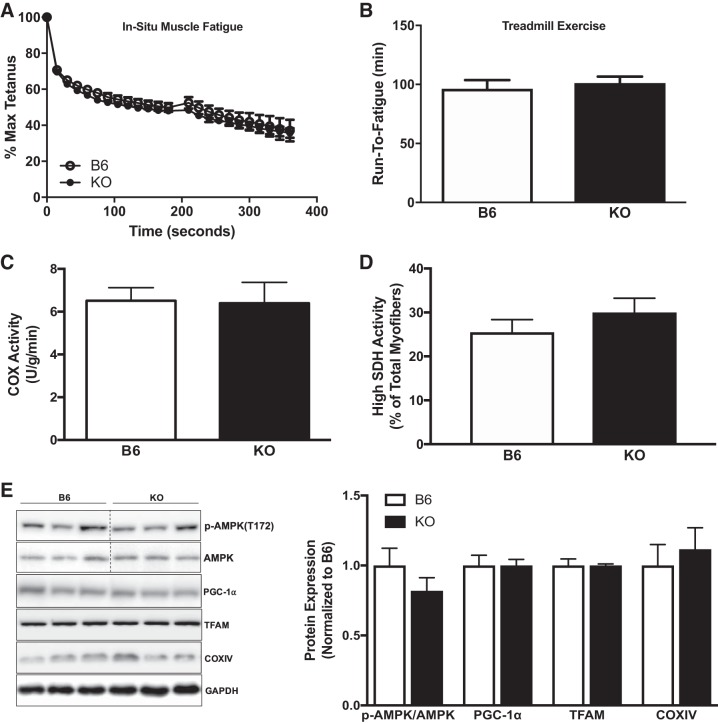

Effects of skeletal muscle-specific gp130 loss on fatigue and mitochondrial content.

To examine the potential role of gp130 in skeletal muscle function and fatigue, we performed whole body and in situ fatigue tests. No differences in either whole body treadmill run-to-fatigue time or tibialis anterior fatigability were observed between KO and B6 mice (Fig. 2, A and B). Interestingly, peak isometric torque was significantly different between B6 (1,674.8 ± 35.2 mN) and KO (1,272.6 ± 35.6 mN) mice (P = 0.004, data not shown). Subsequently, we found no alteration in the COX enzyme activity of crude gastrocnemius homogenate in KO mice (Fig. 2C). In addition, muscle gp130 loss did not alter the percentage of high SDH activity in tibialis anterior myofibers (Fig. 2D). We then investigated the role of gp130 in mitochondrial biogenesis regulation. Muscle gp130 loss did not alter the activation of AMPK, PGC-1α, mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), or COX IV expression (Fig. 2E). These results demonstrate that skeletal muscle gp130 loss does not alter in situ fatigue or indexes of mitochondrial biogenesis and content.

Fig. 2.

Muscle glycoprotein-130 (gp130) loss effects on mitochondrial biogenesis and content. We next examined mitochondrial biogenesis and content in the gastrocnemius muscle of C57BL/6 mice (B6) and mice with skeletal muscle-specific deletion of gp130 receptor (KO). A: in situ muscle fatigue test of tibialis anterior muscle in B6 (n = 5) and KO (n = 5) mice. B: whole body treadmill run time to fatigue in B6 (n = 5) and KO (n = 5) mice. C: cytochrome-c oxidase (COX) enzymatic activity in crude gastrocnemius homogenate from B6 and KO mice. D: high-succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity myofibers expressed as a percentage of total myofibers in B6 and KO mice. E, left: representative immunoblots of phospho (p)-AMPKT172, AMPK, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), COX IV, and GAPDH in B6 and KO mice. Right: quantification of immunoblots. Max, maximum. Total n = 7 B6 mice and 5 KO mice for C–E. All values are reported as means ± SE. All values were normalized to B6. Analyses were conducted using unpaired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

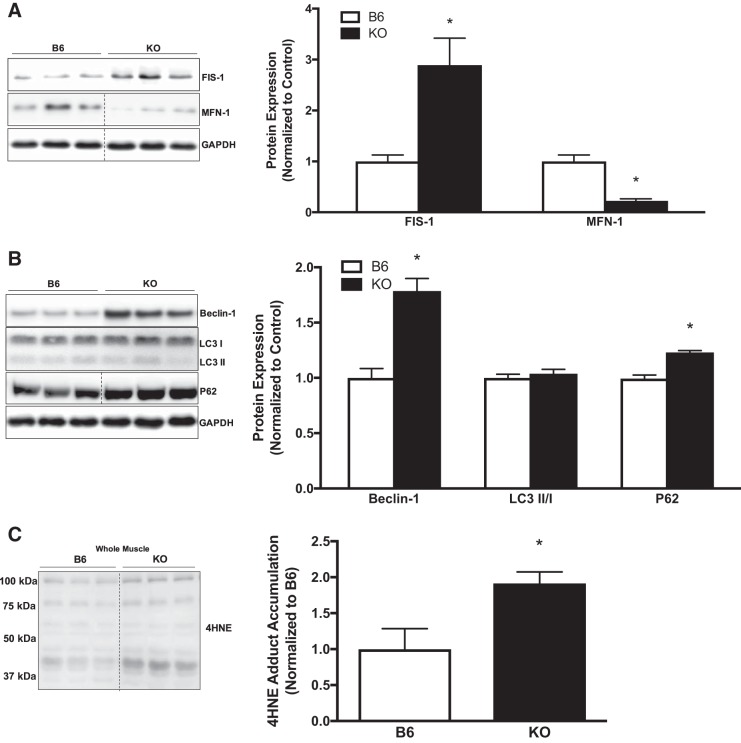

Role of gp130 in skeletal muscle mitochondrial remodeling and autophagy.

To examine a role for gp130 in mitochondrial remodeling, we examined dynamics and autophagy. We examined FIS-1 and MFN-1 protein expression in the crude gastrocnemius muscle of B6 and KO mice. Muscle gp130 loss increased FIS-1 protein expression, whereas MFN-1 protein expression was decreased, which coincides with protein analysis in isolated mitochondria (Fig. 3A). To assess the role of gp130 in skeletal muscle autophagosome formation, we examined upstream regulatory protein Beclin-1, as well as adaptor proteins LC3-I and LC3-II and ubiquitin-binding protein p62 (p62). Muscle gp130 loss induced Beclin-1 protein expression (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, there was no alteration in the ratio of LC3-II protein expression to LC3-I protein expression (LC3-II/I) between B6 and KO mice. Whereas LC3-II was unaltered, there was increased p62 protein expression in KO mice, which is indicative of dysfunctional autophagic clearance or resolution at the whole muscle level (Fig. 3B). In light of these findings we next examined 4-HNE adduct accumulation in B6 and KO mice as a marker of oxidative stress. KO increased 4-HNE protein adduct accumulation (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these results demonstrate a role for gp130 in mitochondrial remodeling through disrupted fission/fusion events, dysfunctional clearance of the autophagosome, and the induction of oxidative stress.

Fig. 3.

Muscle mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy. To further our analysis of mitochondrial quality control, we examined mitochondrial dynamics and indexes of autophagy in gastrocnemius muscle of C57BL/6 mice (B6) and mice with skeletal muscle-specific deletion of gp130 receptor (KO). A, left: representative immunoblots of mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS-1), mitofusin-1 (MFN-1), and GAPDH in B6 and KO mice. Right: quantification of immunoblots. B, left: representative immunoblots of Beclin-1, microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3B (LC3)-I and LC3-II, ubiquitin-binding protein p62 (p62), and GAPDH in B6 and KO mice. Right: quantification of immunoblots. C, left: representative immunoblot of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) adducts in B6 and KO mice. Right: quantification of immunoblot. LC3-II/I, ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I. Total n = 7 B6 mice and 5 KO mice. All values were normalized to B6. All values are reported as means ± SE. Analyses were conducted using unpaired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. *Statistically different from B6.

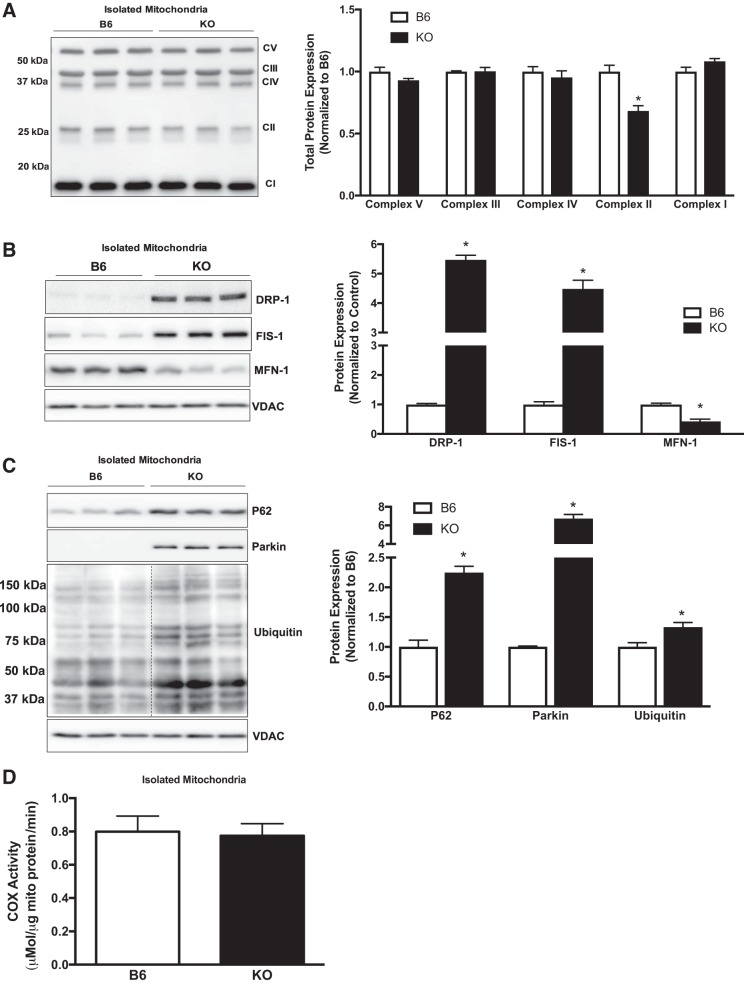

Effect of muscle gp130 loss on isolated mitochondria.

We next examined isolated mitochondria from B6 and KO mice to determine alterations in content, dynamics, and mitophagy that may not be easily detected in whole muscle. Total oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) protein expression demonstrated a decrease at complex II SDH subunit B (SDHB) in KO animals (Fig. 4A). We next examined mitochondrial dynamics proteins DFP-1, FIS-1, and MFN-1. Muscle gp130 loss induced translocation of DRP-1 to the mitochondria and induced FIS-1 (Fig. 4B). Additionally, MFN-1 protein expression was decreased in KO mitochondria (Fig. 4B). To determine mitochondria-specific autophagy (mitophagy), we examined p62, Parkin, and ubiquitin protein expression in isolated mitochondria (Fig. 4B). p62 was translocated to the KO mitochondria, and this coincided with a robust increase in ubiquitin (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, Parkin was only detected in KO mitochondria (Fig. 4C). Surprisingly, COX activity of isolated mitochondria was not altered by KO (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these results demonstrate a role for gp130 in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy and that these changes occur independently of COX activity.

Fig. 4.

Examination of isolated muscle mitochondria. Mitochondria from the gastrocnemius of C57BL/6 mice (B6) and mice with skeletal muscle-specific deletion of gp130 receptor (KO) were isolated and examined for complex protein, mitophagy, and cytochrome-c oxidase (COX) enzymatic activity. A, left: representative immunoblot of total oxidative phosphorylation protein expression in B6 and KO mitochondria. Right: quantification of immunoblot. B, left: representative immunoblots of dynamin-related protein-1 (DRP-1), mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS-1), and mitofusin-1 (MFN-1) in B6 and KO mice. Right: quantification of immunoblots. C, left: representative immunoblots of ubiquitin-binding protein p62 (p62), Parkin, and ubiquitin protein in B6 and KO mitochondria. Right: quantification of immunoblots. Dashed line indicates that blot was cropped for representative purposes. D: COX enzymatic activity in B6 and KO mitochondria. CI–V, complexes I–V; mito, mitochondria; VDAC, voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein. Total n = 6 B6 mice and 6 KO mice. All values are reported as means ± SE. All values were normalized to B6. Analyses were conducted using unpaired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. *Statistically different from B6.

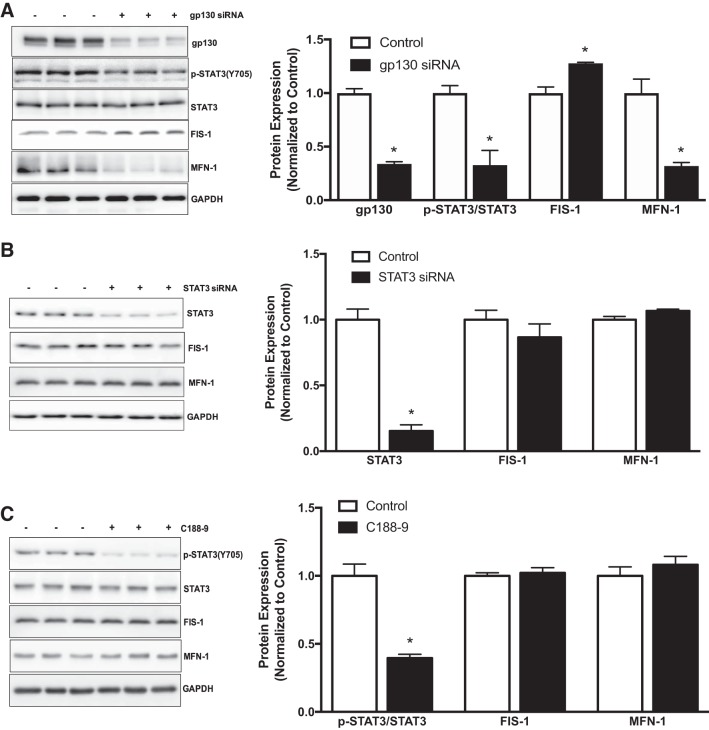

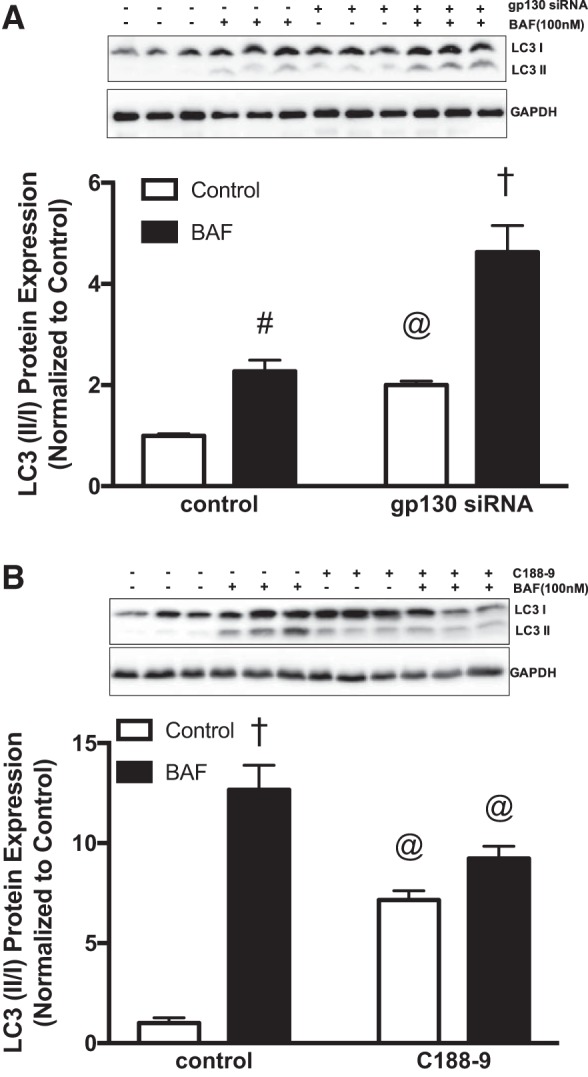

Role of gp130 and STAT3 in mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy in siRNA-transfected C2C12 myotubes.

To further confirm our in vivo findings and mechanistically examine gp130’s role in mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy, we treated fully differentiated myotubes with control and gp130 siRNA. In differentiated myotubes, gp130 siRNA was sufficient to suppress gp130 protein expression and downstream STAT3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5A). We then examined mitochondrial dynamics in gp130 siRNA-transfected myotubes. In accordance with our in vivo results, gp130 siRNA increased FIS-1 protein expression while suppressing MFN-1 protein expression (Fig. 5A). Since gp130 modulated FIS-1 and MFN-1 in KO mice and gp130 siRNA-transfected myotubes, we next investigated whether these changes in mitochondrial dynamic proteins were mediated by downstream STAT3 signaling. Thus, we evaluated FIS-1 and MFN-1 protein expression in myotubes treated with two STAT3 inhibitors (STAT3 siRNA and C188-9). As expected, STAT3 siRNA and C188-9 inhibited basal STAT3 (Fig. 5, B and C). However, no changes in either FIS-1 or MFN-1 protein expression were observed in cultured C2C12 myotubes treated with STAT3 siRNA or C188-9 (Fig. 5, B and C). To mechanistically examine gp130’s role in autophagosome formation, fully differentiated myotubes were treated with bafilomycin (lysosomal inhibitor) for 3 h. In control siRNA myotubes, bafilomycin treatment increased accumulation of LC3-II/I as expected (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, LC3-II/I accumulation was further increased by gp130 in myotubes (Fig. 6A). To determine the potential involvement of STAT3 in the regulation of autophagosome formation, we next measured protein accumulation of LC3-II/I in bafilomycin-treated myotubes. Administration of bafilomycin A1 alone significantly increased protein accumulation of LC3-II/I (Fig. 6B). C188-9 treatment also induced protein accumulation of LC3-II/I; however, there was no further accumulation of LC3-II/I with the combination of C188-9 and bafilomycin (Fig. 6B). Overall, these results suggest a role for muscle gp130 in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics and autophagosome formation. The regulation of mitochondrial dynamics by gp130 occurs independently of STAT3. However, these results also suggest a role for STAT3 in regulating autophagosome formation.

Fig. 5.

Mitochondrial dynamics in C2C12 myotubes treated with glycoprotein-130 (gp130) and STAT3 inhibitors. To mechanistically investigate our mitochondrial dynamics findings in muscle, we treated C2C12 myotubes with gp130 siRNA and two STAT3 inhibitors. A, left: representative immunoblot of gp130, phospho (p)-STAT3Y705, STAT3, mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS-1), mitofusin-1 (MFN-1), and GAPDH in myotubes treated with gp130 siRNA. Right: quantification of immunoblots. B, left: representative immunoblots of STAT3, FIS-1, MFN-1, and GAPDH in myotubes treated with STAT3 siRNA. Right: quantification of immunoblots. C, left: representative immunoblots of p-STAT3Y705, STAT3, FIS-1, MFN-1, and GAPDH in myotubes treated with STAT3Y705-specific inhibitor C188-9. Right: quantification of immunoblots. All values were normalized to control. All values are reported as means ± SE. Analyses were conducted using Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. *Statistically different from control.

Fig. 6.

Autophagy in C2C12 myotubes treated with glycoprotein-130 (gp130) and STAT3 inhibitors. To investigate the role of gp130 and STAT3 in autophagosome formation, we treated C2C12 myotubes with bafilomycin A1 (BAF; 100 nM) for 3 h in the presence of gp130 siRNA and STAT3Y705-specific inhibitor C188-9. A, top: representative immunoblots of microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3B (LC3)-I, LC3-II, and GAPDH protein in myotubes treated with gp130 siRNA and bafilomycin A1. Bottom: quantification of immunoblots above. B, top: representative immunoblots of LC3-I, LC3-II, and GAPDH protein in myotubes treated with C188-9 and bafilomycin A1. Bottom: quantification of immunoblots above. LC3-II/I, ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I. All values are reported as means ± SE. Analyses were conducted using unpaired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. @Main effect of gp130 siRNA or c188-9. #Main effect of BAF. †Statistically different from all groups.

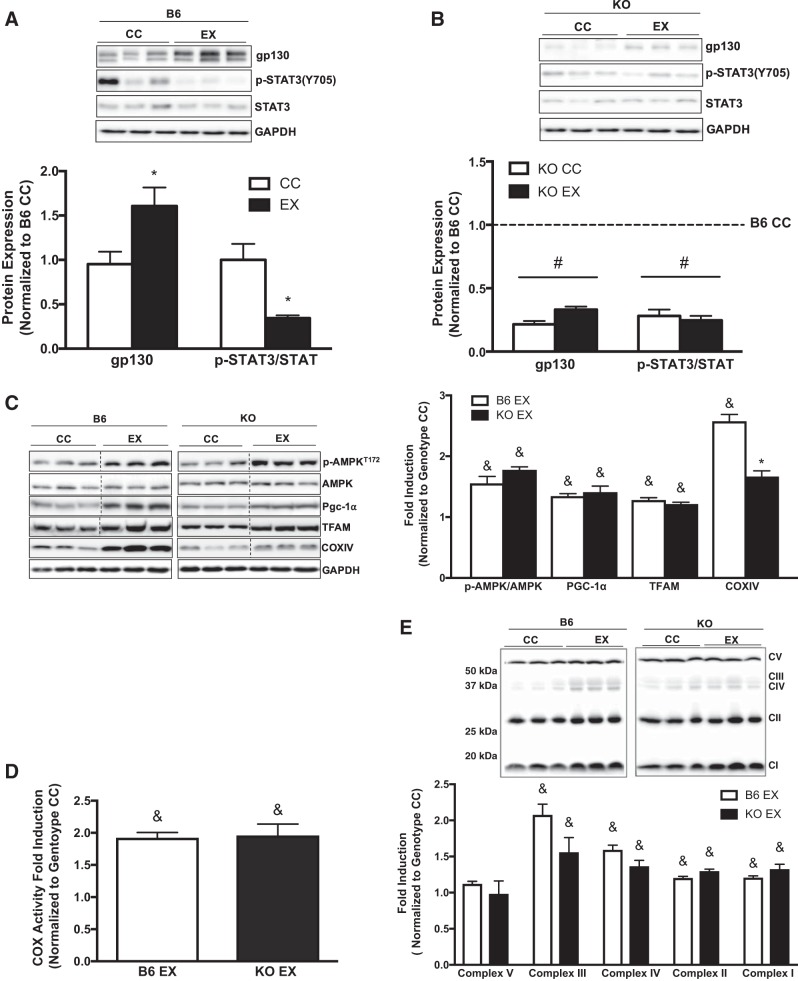

Effects of skeletal muscle-specific gp130 loss on mitochondrial biogenesis and content following exercise training.

We next examined whether skeletal muscle gp130 loss altered the adaptive response to 6 wk of treadmill exercise training. Whereas exercise training significantly increased muscle gp130 protein expression in B6 mice, STAT3 phosphorylation was significantly reduced in gastrocnemius muscle of B6 mice (Fig. 7A). In contrast, gp130 protein expression and STAT3 phosphorylation were decreased in KO muscle regardless of exercise training (Fig. 7B). Additionally, IL-6 mRNA expression was not altered by exercise training or muscle gp130 loss (data not shown). Given that exercise training increases muscle COX activity and COX IV mRNA after aerobic exercise training (7, 39), we also investigated whether muscle gp130 loss in skeletal muscle affected COX enzyme activity and protein expression related to mitochondrial biogenesis/content. Muscle gp130 loss did not alter the exercise-training induction of AMPK, PGC-1α, or TFAM (Fig. 7C). Moreover, the exercise-training increase in COX enzyme activity was not altered by gp130 loss (Fig. 7D). Surprisingly, the exercise-training induction of COX IV protein was blunted in KO mice (Fig. 7C). Additionally, we examined protein expression of total OXPHOS complex proteins in the gastrocnemius muscle of B6 and KO mice. Exercise training increased total OXPHOS protein expression for complexes I–IV in B6 mice, and this induction was not altered by muscle gp130 loss (Fig. 7E). These results suggest that skeletal muscle gp130 expression is induced during exercise training and is not required for the exercise-training induction of mitochondrial content and biogenesis.

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial biogenesis and content following exercise training. We next examined the effect of muscle glycoprotein-130 (gp130) loss on gastrocnemius mitochondrial biogenesis and content following 6 wk of treadmill exercise training. A, top: representative immunoblots of gp130, phospho (p)-STAT3Y705, STAT3, and GAPDH in C57BL/6 (B6) exercise-trained (EX) mice. Bottom: quantification of immunoblots above. B, top: representative immunoblots of gp130, p-STAT3Y705, STAT3, and GAPDH in skeletal muscle-specific gp130 knockout (KO) EX mice. Bottom: quantification of immunoblots above. C, left: representative immunoblots of p-AMPKT172, AMPK, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), cytochrome-c oxidase subunit IV (COX IV), and GAPDH in B6 and KO EX mice. Right: quantification of immunoblots. D: COX enzymatic activity in B6 and KO EX mice. E, top: representative immunoblot of total oxidative phosphorylation protein expression in B6 and KO EX mice. Bottom: quantification of immunoblot above. CC, cage control; CI–V, complexes I–V. Total n = 7 B6 CC mice and 5 KO CC mice, n = 11 B6 EX and 7 KO EX mice. All values were normalized to each genotype’s respective CC. All samples were run on common gels to directly compare samples. Analyses were conducted using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis where appropriate. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. *Statistically different from CC. #Main effect of KO. &Main effect of exercise.

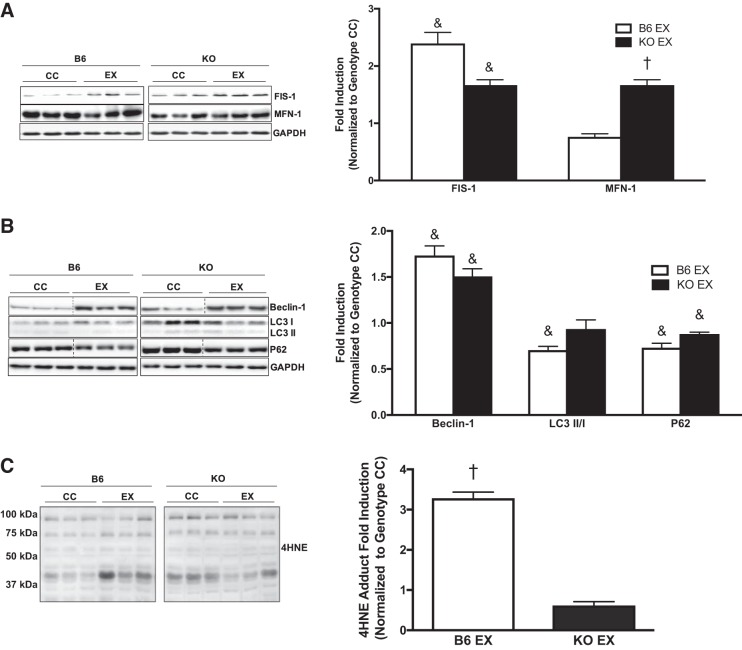

Effects of skeletal muscle gp130 loss on mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy following exercise training.

To further examine whether skeletal muscle loss of gp130 in exercise-trained mice altered proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy, we measured the protein expression of FIS-1, MFN-1, Beclin-1, LC3-II/I, and p62 in the gastrocnemius muscle of B6 and KO mice. Exercise training significantly increased FIS-1 protein expression irrespective of gp130 loss (Fig. 8A). Whereas exercise training did not affect MFN-1 protein expression in B6 mice, exercise training increased MFN-1 protein expression in KO mice (Fig. 8A). The exercise-training induction of Beclin-1 protein expression was not altered by gp130 receptor loss (Fig. 8B). However, the exercise-training reduction in LC3-II/I was not observed in KO mice (Fig. 8B). Exercise training decreased p62 protein expression, which was not altered by muscle gp130 loss (Fig. 8B). Additionally, 4-HNE adduct accumulation was increased in B6 mice following exercise training, and this induction was blocked by muscle gp130 loss (Fig. 8C). These results suggest that gp130 is not necessary for the exercise-training induction of mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy.

Fig. 8.

Mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy following exercise training. We examined gastrocnemius muscle mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy in C57BL/6 (B6) and skeletal muscle-specific gp130 knockout (KO) mice following 6 wk of treadmill exercise training. A, left: representative immunoblots of mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS-1), mitofusin-1 (MFN-1), and GAPDH in B6 and KO exercise-trained (EX) mice. Right: quantification of immunoblots. B, left: representative immunoblots of Beclin-1, microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3B (LC3)-I and LC3-II, ubiquitin-binding protein p62 (p62), and GAPDH in B6 and KO EX mice. Right: quantification of immunoblots. C, left: representative immunoblot of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) adducts in B6 and KO EX mice. Right: quantification of immunoblot. CC, cage control. LC3-II/I, ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I. Total n = 7 B6 CC and 5 KO CC mice, n = 11 B6 EX and 7 KO EX mice. All values were normalized to each genotype’s respective CC. All values are reported as means ± SE. Analyses were conducted using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis where appropriate. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. &Main effect of exercise. †Statistically different from all groups.

DISCUSSION

During the past 15 years, our understanding of the importance of the IL-6 cytokine family has developed rapidly (17, 43). However, complexities related to global cytokine action have limited our understanding of direct skeletal muscle regulation by this family. The IL-6 family induces many systemic effects that can indirectly regulate skeletal muscle signaling, and whole body knockout mice have provided much of our knowledge on cytokine action with exercise and disease. Although chronically elevated plasma IL-6 is associated with disrupted oxidative metabolism and metabolic plasticity (65), less evidence exists for a direct regulatory role of these cytokines on muscle mitochondrial quality in either the sedentary or the trained state. Our results suggest a role for muscle gp130 signaling in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics, autophagosome formation/clearance, and mitophagy. Interestingly, muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and content were independent of gp130 signaling in the basal and trained states. However, skeletal muscle mitochondrial dynamics, autophagosome formation/clearance, mitophagy, and oxidative stress were targets of gp130. Interestingly, STAT3 activation was not required for proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics, which implicates other signaling pathways downstream of gp130 for this regulation. However, basal STAT3 inhibition induced autophagosome formation via LC3-II/I accumulation in myotubes. Collectively, our results suggest that gp130 receptor signaling can disrupt muscle mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, and autophagosome formation/clearance during basal and exercise-trained conditions and that these processes occur independently of muscle function and mitochondrial content.

Muscle mitochondrial quality has an established role in overall systemic health (11, 24, 65). The IL-6/gp130 signaling pathway has been linked to mitochondrial function through STAT3 activation (40, 56). Although STAT3 signaling can regulate basal respiration (16), STAT3 accumulation in the mitochondria has been implicated in the formation of reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial dysfunction (64). Chronic disease and acute exercise can increase circulating plasma IL-6 and activate STAT3 (37, 48, 51), which has been associated with decreased mitochondrial content and the suppression of PGC-1α (45, 65). We have previously demonstrated that muscle-specific gp130 loss is sufficient to block STAT3 activation during cancer cachexia (45), and muscle gp130 loss suppressed basal STAT3 activity in the present study. We report the novel finding that exercise training induced muscle gp130 protein expression while attenuating muscle STAT3 activation in wild-type mice. Since exercise training can decrease circulating plasma IL-6 (12, 15), the exercise-training induction of muscle gp130 expression likely serves to increase the muscle’s cytokine sensitivity. Additionally, there was no alteration in IL-6 mRNA expression with muscle gp130 loss or exercise training. Collectively, these findings point toward indirect IL-6 action in the regulation of skeletal muscle mitochondrial dynamics and indexes of autophagy.

The examination of mice with global IL-6 loss has implicated a role for IL-6 in oxidative metabolism responsiveness to exercise (14, 37, 68). Whereas exercise training increased COX activity (22, 24), we report that muscle gp130 loss, which resulted in a reduction in STAT3 activity, had no effect on basal or exercise training-induced COX activity, AMPK, PGC-1α, or TFAM protein expression. Mitochondrial complex II (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD) is responsible for linking the Krebs cycle to the electron transport chain (18), whereas deficits in SDHA are linked to various metabolic diseases and decreased Krebs cycle activity (47). The enzymatic activity of SDH can remain intact if an alteration occurs to any subunit but SDHA (18). The iron-sulfur subunit of this complex (SDHB) is responsible for the removal of the electrons from SDHA and the transfer to ubiquinone. The disruption of this transfer process will leave the bioenergetic activity of SDH intact but induce oxidation of the reduced flavin group by O2, thus increasing production of reactive oxygen species (47). Recently, pharmacological inhibition of complex II (SDHB) has been demonstrated to increase the production of reactive oxygen species in nonmuscle cells (18). The increased production of reactive oxygen species can have important physiological ramifications. The induction of reactive oxygen species production can disrupt cellular signaling processes, alter the oxidation status of mitochondria, and increase mitophagy processes (32). In the present study, the suppression of complex II in KO mitochondria did not alter whole muscle SDH enzymatic activity and was concomitant with an accumulation of 4-HNE adducts in whole muscle, indicative of increased reactive oxygen species. However, complex II expression was rescued with exercise training, and the basal induction of 4-HNE was attenuated in KO mice, demonstrating a therapeutic effect of exercise training. Further research is warranted to explore the mechanisms linking gp130 signaling to reactive oxygen species generation in muscle, as differences could also be due to the expression of antioxidant defense pathways.

The regulated expression of proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy is critical for maintaining mitochondrial function and responsiveness to a variety of conditions (6, 11). Mitochondrial dynamics, the coordinated regulation of mitochondrial fission and fusion processes, is an essential process for the physiological response to metabolic stress (49, 50, 70). Disrupted muscle mitochondrial dynamics have been associated with increased reactive oxygen species, autophagy/mitophagy, and ubiquitin proteasome activity (33, 35, 59). We report the novel finding that gp130 signaling alters basal proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics in skeletal muscle and cultured myotubes. The induction of basal FIS-1 protein expression and the suppression of MFN-1 protein expression were found with both skeletal muscle gp130 loss and siRNA gp130 knockdown in myotubes. Additionally, these findings were corroborated in isolated mitochondria of KO animals. We also report the novel finding that muscle gp130 was not necessary for the exercise-training induction of FIS-1. Interestingly, our present study did not find STAT3 regulation of either FIS-1 or MFN-1 protein expression in cultured myotubes. This demonstrates that gp130-mediated perturbations to mitochondrial dynamics occur through a STAT3-independent mechanism in the basal state. However, further work is needed to examine FIS-1 regulation in muscle with chronically activated STAT3 signaling, which is what occurs with many wasting diseases (41, 65, 66). Although STAT3 is often described as the canonical pathway for the intracellular action of the IL-6 family of cytokines, other signaling pathways are downstream of the gp130 receptor (9, 13), such as MAPK and Akt signaling. We have previously demonstrated that gp130 loss in skeletal muscle can alter the induction of muscle p38, MAPK, NF-κB, and STAT3 signaling (45). A limitation of our analysis is that we only measured protein expression of mitochondrial dynamics machinery and were unable to visually analyze the morphology of mitochondria using electron microscopy.

Increased reactive oxygen species and altered mitochondrial dynamics can accelerate autophagy/mitophagy (58, 70). Autophagy is essential for basal metabolic homeostasis and is typically a nonselective process that has been studied extensively with acute exercise and exercise training (19, 34, 58, 60, 70). Beclin-1, involved in autophagosome formation and maturation, is increased with exercise training and chronic diseases (21, 28). Beclin-1’s importance in the autophagy process is paramount; inhibition can lead to damaged and dysfunctional organelle accumulation (21, 28, 70). A ubiquitin-binding scaffold protein, p62 is involved in autophagosome clearance/resolution (1). Upon binding to ubiquitin-tagged organelles and protein aggregates, p62 will serve to deliver the tagged cargo to the lysosomal proteasome system (31). We demonstrate that muscle gp130 loss induces both Beclin-1 and p62 protein expression in the basal state and that this occurs independently of any alterations in LC3-II/I. We also report that exercise training reduced p62 expression in B6 and KO mice, demonstrating that exercise training increased clearance of the autophagosome and may be indicative of a more efficient autophagic response. These results suggest an impairment of lysosomal activity with the accumulation of p62 in KO mice and the therapeutic effect of exercise training to correct this dysfunction (31). Surprisingly, knockdown of gp130 in myotubes induced LC3-II/I accumulation, which was further induced with bafilomycin treatment. These contradictory findings regarding LC3-II/I accumulation likely point to the distinct autophagic degradation kinetics of these substrates in mature skeletal muscle compared with cell culture (29). Interestingly, STAT3 suppression in myotubes also induced basal LC3-II/I protein accumulation. This LC3-II/I accumulation by STAT3 inhibition was not further induced with bafilomycin, likely because of an impairment of lysosomal capacity for autophagosome degradation. The apparent induction of LC3-I alone suggests that STAT3 may transcriptionally control this process. The selective turnover of mitochondria through mitophagy has recently become an interesting target of investigation in skeletal muscle biology with exercise and disease (61). Parkin is recruited by phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-induced putative kinase-1 (PINK1) and serves to ubiquinate damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria for turnover (32). In the present study, Parkin was only detected in KO mitochondria and was accompanied by the translocation of p62 and ubiquitin, suggesting that a loss of muscle gp130 signaling induces mitophagy. Collectively, these findings suggest a role for gp130/STAT3 signaling in autophagic and mitophagic processes. These processes may serve as a compensatory mechanism related to disrupted mitochondrial dynamics and increased reactive oxygen species occurring through suppression of complex II. Further work is warranted to determine whether the alterations to the autophagosomal response and mitophagy due to gp130 loss are important for the maintenance of oxidative metabolism in the skeletal muscles from gp130 knockout mice, which would enhance the removal of damaged organelles caused by elevated oxidative stress and increased mitochondrial fission.

In conclusion, our results establish a role for muscle gp130 signaling in mitochondrial quality control. Additionally, we report that muscle gp130 signaling is not necessary for the exercise-training induction of mitochondrial content and dynamics. However, basal changes in FIS-1, MFN-1, and Beclin-1 expression were regulated by skeletal muscle gp130 signaling. Interestingly, these changes occurred via a STAT3-independent mechanism in cultured myotubes. Our results also suggest that gp130 signaling may regulate skeletal muscle mitophagy. Additional studies are necessary to corroborate the effects of the gp130 receptor on FIS-1 and MFN-1 proteins with morphological changes in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Although our data establish a role for gp130 in mitochondrial quality control, a limitation of our analysis is a lack of mitochondrial respiration, and we consider this a critical future direction. Further research is also warranted to elucidate which downstream gp130 signaling, independent of STAT3, is important for skeletal muscle mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy/mitophagy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grants R01-CA-121249 (J. A. Carson) and 07S1-CA-121249 (K. T. Velázquez) and National Center for Research Resources Grant P20-RR-017698.

DISCLAIMERS

Contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or NIH.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.A.C. conceived and designed research; D.K.F., J.P.H., S.G., B.N.V., and K.T.V. performed experiments; D.K.F., J.P.H., S.G., B.N.V., and K.T.V. analyzed data; D.K.F., J.P.H., and J.A.C. interpreted results of experiments; D.K.F. prepared figures; D.K.F. drafted manuscript; J.P.H., K.T.V., and J.A.C. edited and revised manuscript; J.A.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ryan N. Montalvo and Gaye Christmus for editorial review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aversa Z, Pin F, Lucia S, Penna F, Verzaro R, Fazi M, Colasante G, Tirone A, Rossi Fanelli F, Ramaccini C, Costelli P, Muscaritoli M. Autophagy is induced in the skeletal muscle of cachectic cancer patients. Sci Rep 6: 30340, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep30340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baltgalvis KA, Berger FG, Peña MM, Davis JM, Carson JA. Effect of exercise on biological pathways in ApcMin/+ mouse intestinal polyps. J Appl Physiol (1985) 104: 1137–1143, 2008. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00955.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baltgalvis KA, Berger FG, Peña MM, Davis JM, White JP, Carson JA. Activity level, apoptosis, and development of cachexia in ApcMin/+ mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 109: 1155–1161, 2010. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00442.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutagy NE, Pyne E, Rogers GW, Ali M, Hulver MW, Frisard MI. Isolation of mitochondria from minimal quantities of mouse skeletal muscle for high throughput microplate respiratory measurements. J Vis Exp 105: e53217, 2015. doi: 10.3791/53217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannavino J, Brocca L, Sandri M, Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA. PGC1-α over-expression prevents metabolic alterations and soleus muscle atrophy in hindlimb unloaded mice. J Physiol 592: 4575–4589, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.275545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson JA, Hardee JP, VanderVeen BN. The emerging role of skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism as a biological target and cellular regulator of cancer-induced muscle wasting. Semin Cell Dev Biol 54: 53–67, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cartoni R, Léger B, Hock MB, Praz M, Crettenand A, Pich S, Ziltener JL, Luthi F, Dériaz O, Zorzano A, Gobelet C, Kralli A, Russell AP. Mitofusins 1/2 and ERRα expression are increased in human skeletal muscle after physical exercise. J Physiol 567: 349–358, 2005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chomentowski P, Coen PM, Radiková Z, Goodpaster BH, Toledo FG. Skeletal muscle mitochondria in insulin resistance: differences in intermyofibrillar versus subsarcolemmal subpopulations and relationship to metabolic flexibility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: 494–503, 2011. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cron L, Allen T, Febbraio MA. The role of gp130 receptor cytokines in the regulation of metabolic homeostasis. J Exp Biol 219: 259–265, 2016. doi: 10.1242/jeb.129213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding H, Jiang N, Liu H, Liu X, Liu D, Zhao F, Wen L, Liu S, Ji LL, Zhang Y. Response of mitochondrial fusion and fission protein gene expression to exercise in rat skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta 1800: 250–256, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drake JC, Wilson RJ, Yan Z. Molecular mechanisms for mitochondrial adaptation to exercise training in skeletal muscle. FASEB J 30: 13–22, 2016. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-276337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egan B, Zierath JR. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell Metab 17: 162–184, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst M, Jenkins BJ. Acquiring signalling specificity from the cytokine receptor gp130. Trends Genet 20: 23–32, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fäldt J, Wernstedt I, Fitzgerald SM, Wallenius K, Bergström G, Jansson JO. Reduced exercise endurance in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Endocrinology 145: 2680–2686, 2004. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer CP, Plomgaard P, Hansen AK, Pilegaard H, Saltin B, Pedersen BK. Endurance training reduces the contraction-induced interleukin-6 mRNA expression in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E1189–E1194, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00206.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gough DJ, Corlett A, Schlessinger K, Wegrzyn J, Larner AC, Levy DE. Mitochondrial STAT3 supports Ras-dependent oncogenic transformation. Science 324: 1713–1716, 2009. doi: 10.1126/science.1171721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudiksen A, Schwartz CL, Bertholdt L, Joensen E, Knudsen JG, Pilegaard H. Lack of skeletal muscle IL-6 affects pyruvate dehydrogenase activity at rest and during prolonged exercise. PLoS One 11: e0156460, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guzy RD, Sharma B, Bell E, Chandel NS, Schumacker PT. Loss of the SdhB, but not the SdhA, subunit of complex II triggers reactive oxygen species-dependent hypoxia-inducible factor activation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol 28: 718–731, 2008. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01338-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halling JF, Ringholm S, Nielsen MM, Overby P, Pilegaard H. PGC-1α promotes exercise-induced autophagy in mouse skeletal muscle. Physiol Rep 4: e12698, 2016. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardee JP, Mangum JE, Gao S, Sato S, Hetzler KL, Puppa MJ, Fix DK, Carson JA. Eccentric contraction-induced myofiber growth in tumor-bearing mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 120: 29–37, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00416.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He C, Bassik MC, Moresi V, Sun K, Wei Y, Zou Z, An Z, Loh J, Fisher J, Sun Q, Korsmeyer S, Packer M, May HI, Hill JA, Virgin HW, Gilpin C, Xiao G, Bassel-Duby R, Scherer PE, Levine B. Exercise-induced BCL2-regulated autophagy is required for muscle glucose homeostasis. Nature 481: 511–515, 2012. [Erratum in Nature 503: 146, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nature12747.] doi:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hood DA. Mechanisms of exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 34: 465–472, 2009. doi: 10.1139/H09-045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hood DA, Tryon LD, Vainshtein A, Memme J, Chen C, Pauly M, Crilly MJ, Carter H. Exercise and the regulation of mitochondrial turnover. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 135: 99–127, 2015. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hood DA, Uguccioni G, Vainshtein A, D’souza D. Mechanisms of exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle: implications for health and disease. Compr Physiol 1: 1119–1134, 2011. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iqbal S, Hood DA. The role of mitochondrial fusion and fission in skeletal muscle function and dysfunction. Front Biosci 20: 157–172, 2015. doi: 10.2741/4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iqbal S, Ostojic O, Singh K, Joseph AM, Hood DA. Expression of mitochondrial fission and fusion regulatory proteins in skeletal muscle during chronic use and disuse. Muscle Nerve 48: 963–970, 2013. doi: 10.1002/mus.23838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jheng HF, Tsai PJ, Guo SM, Kuo LH, Chang CS, Su IJ, Chang CR, Tsai YS. Mitochondrial fission contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Biol 32: 309–319, 2012. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05603-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ju JS, Jeon SI, Park JY, Lee JY, Lee SC, Cho KJ, Jeong JM. Autophagy plays a role in skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in an endurance exercise-trained condition. J Physiol Sci 66: 417–430, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s12576-016-0440-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ju JS, Varadhachary AS, Miller SE, Weihl CC. Quantitation of “autophagic flux” in mature skeletal muscle. Autophagy 6: 929–935, 2010. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.12785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly M, Gauthier MS, Saha AK, Ruderman NB. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by interleukin-6 in rat skeletal muscle: association with changes in cAMP, energy state, and endogenous fuel mobilization. Diabetes 58: 1953–1960, 2009. doi: 10.2337/db08-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komatsu M, Ichimura Y. Physiological significance of selective degradation of p62 by autophagy. FEBS Lett 584: 1374–1378, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laker RC, Drake JC, Wilson RJ, Lira VA, Lewellen BM, Ryall KA, Fisher CC, Zhang M, Saucerman JJ, Goodyear LJ, Kundu M, Yan Z. Ampk phosphorylation of Ulk1 is required for targeting of mitochondria to lysosomes in exercise-induced mitophagy. Nat Commun 8: 548, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00520-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JY, Kapur M, Li M, Choi MC, Choi S, Kim HJ, Kim I, Lee E, Taylor JP, Yao TP. MFN1 deacetylation activates adaptive mitochondrial fusion and protects metabolically challenged mitochondria. J Cell Sci 127: 4954–4963, 2014. doi: 10.1242/jcs.157321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lira VA, Okutsu M, Zhang M, Greene NP, Laker RC, Breen DS, Hoehn KL, Yan Z. Autophagy is required for exercise training-induced skeletal muscle adaptation and improvement of physical performance. FASEB J 27: 4184–4193, 2013. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-228486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lo Verso F, Carnio S, Vainshtein A, Sandri M. Autophagy is not required to sustain exercise and PRKAA1/AMPK activity but is important to prevent mitochondrial damage during physical activity. Autophagy 10: 1883–1894, 2014. doi: 10.4161/auto.32154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mangum JE, Hardee JP, Fix DK, Puppa MJ, Elkes J, Altomare D, Bykhovskaya Y, Campagna DR, Schmidt PJ, Sendamarai AK, Lidov HG, Barlow SC, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Fleming MD, Carson JA, Patton JR. Pseudouridine synthase 1 deficient mice, a model for mitochondrial myopathy with sideroblastic anemia, exhibit muscle morphology and physiology alterations. Sci Rep 6: 26202, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep26202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGinnis GR, Ballmann C, Peters B, Nanayakkara G, Roberts M, Amin R, Quindry JC. Interleukin-6 mediates exercise preconditioning against myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H1423–H1433, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00850.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mehl KA, Davis JM, Clements JM, Berger FG, Pena MM, Carson JA. Decreased intestinal polyp multiplicity is related to exercise mode and gender in ApcMin/+ mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 98: 2219–2225, 2005. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00975.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menshikova EV, Ritov VB, Toledo FG, Ferrell RE, Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE. Effects of weight loss and physical activity on skeletal muscle mitochondrial function in obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288: E818–E825, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00322.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Narsale AA, Carson JA. Role of interleukin-6 in cachexia: therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 8: 321–327, 2014. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narsale AA, Puppa MJ, Hardee JP, VanderVeen BN, Enos RT, Murphy EA, Carson JA. Short-term pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate administration attenuates cachexia-induced alterations to muscle and liver in ApcMin/+ mice. Oncotarget 7: 59482–59502, 2016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Neill HM, Palanivel R, Wright DC, MacDonald T, Lally JS, Schertzer JD, Steinberg GR. IL-6 is not essential for exercise-induced increases in glucose uptake. J Appl Physiol (1985) 114: 1151–1157, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00946.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedersen BK. Muscular interleukin-6 and its role as an energy sensor. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44: 392–396, 2012. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31822f94ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petersen EW, Carey AL, Sacchetti M, Steinberg GR, Macaulay SL, Febbraio MA, Pedersen BK. Acute IL-6 treatment increases fatty acid turnover in elderly humans in vivo and in tissue culture in vitro. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288: E155–E162, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00257.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puppa MJ, Gao S, Narsale AA, Carson JA. Skeletal muscle glycoprotein 130’s role in Lewis lung carcinoma-induced cachexia. FASEB J 28: 998–1009, 2014. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-240580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puppa MJ, White JP, Velázquez KT, Baltgalvis KA, Sato S, Baynes JW, Carson JA. The effect of exercise on IL-6-induced cachexia in the ApcMin/+ mouse. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 3: 117–137, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s13539-011-0047-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinlan CL, Orr AL, Perevoshchikova IV, Treberg JR, Ackrell BA, Brand MD. Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. J Biol Chem 287: 27255–27264, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reihmane D, Dela F. Interleukin-6: possible biological roles during exercise. Eur J Sport Sci 14: 242–250, 2014. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2013.776640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romanello V, Guadagnin E, Gomes L, Roder I, Sandri C, Petersen Y, Milan G, Masiero E, Del Piccolo P, Foretz M, Scorrano L, Rudolf R, Sandri M. Mitochondrial fission and remodelling contributes to muscle atrophy. EMBO J 29: 1774–1785, 2010. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romanello V, Sandri M. Mitochondrial quality control and muscle mass maintenance. Front Physiol 6: 422, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sako H, Yada K, Suzuki K. Genome-wide analysis of acute endurance exercise-induced translational regulation in mouse skeletal muscle. PLoS One 11: e0148311, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saleem A, Adhihetty PJ, Hood DA. Role of p53 in mitochondrial biogenesis and apoptosis in skeletal muscle. Physiol Genomics 37: 58–66, 2009. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90346.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanchez AM, Csibi A, Raibon A, Cornille K, Gay S, Bernardi H, Candau R. AMPK promotes skeletal muscle autophagy through activation of forkhead FoxO3a and interaction with Ulk1. J Cell Biochem 113: 695–710, 2012. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serrano AL, Baeza-Raja B, Perdiguero E, Jardí M, Muñoz-Cánoves P. Interleukin-6 is an essential regulator of satellite cell-mediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell Metab 7: 33–44, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sin J, Andres AM, Taylor DJR, Weston T, Hiraumi Y, Stotland A, Kim BJ, Huang C, Doran KS, Gottlieb RA. Mitophagy is required for mitochondrial biogenesis and myogenic differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts. Autophagy 12: 369–380, 2016. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1115172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith IJ, Godinez GL, Singh BK, McCaughey KM, Alcantara RR, Gururaja T, Ho MS, Nguyen HN, Friera AM, White KA, McLaughlin JR, Hansen D, Romero JM, Baltgalvis KA, Claypool MD, Li W, Lang W, Yam GC, Gelman MS, Ding R, Yung SL, Creger DP, Chen Y, Singh R, Smuder AJ, Wiggs MP, Kwon OS, Sollanek KJ, Powers SK, Masuda ES, Taylor VC, Payan DG, Kinoshita T, Kinsella TM. Inhibition of Janus kinase signaling during controlled mechanical ventilation prevents ventilation-induced diaphragm dysfunction. FASEB J 28: 2790–2803, 2014. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-244210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suliman HB, Piantadosi CA. Mitochondrial quality control as a therapeutic target. Pharmacol Rev 68: 20–48, 2016. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vainshtein A, Hood DA. The regulation of autophagy during exercise in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 120: 664–673, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00550.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vainshtein A, Kazak L, Hood DA. Effects of endurance training on apoptotic susceptibility in striated muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 110: 1638–1645, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00020.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vainshtein A, Tryon LD, Pauly M, Hood DA. Role of PGC-1α during acute exercise-induced autophagy and mitophagy in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 308: C710–C719, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00380.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.VanderVeen BN, Fix DK, Carson JA. Disrupted skeletal muscle mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, and biogenesis during cancer cachexia: a role for inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017: 3292087, 2017. doi: 10.1155/2017/3292087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.VanderVeen BN, Hardee JP, Fix DK, Carson JA. Skeletal muscle function during the progression of cancer cachexia in the male ApcMin/+ mouse. J Appl Physiol (1985) 124: 684–695, 2018. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00897.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Washington TA, White JP, Davis JM, Wilson LB, Lowe LL, Sato S, Carson JA. Skeletal muscle mass recovery from atrophy in IL-6 knockout mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 202: 657–669, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wegrzyn J, Potla R, Chwae YJ, Sepuri NB, Zhang Q, Koeck T, Derecka M, Szczepanek K, Szelag M, Gornicka A, Moh A, Moghaddas S, Chen Q, Bobbili S, Cichy J, Dulak J, Baker DP, Wolfman A, Stuehr D, Hassan MO, Fu XY, Avadhani N, Drake JI, Fawcett P, Lesnefsky EJ, Larner AC. Function of mitochondrial Stat3 in cellular respiration. Science 323: 793–797, 2009. doi: 10.1126/science.1164551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.White JP, Baltgalvis KA, Puppa MJ, Sato S, Baynes JW, Carson JA. Muscle oxidative capacity during IL-6-dependent cancer cachexia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R201–R211, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00300.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White JP, Puppa MJ, Sato S, Gao S, Price RL, Baynes JW, Kostek MC, Matesic LE, Carson JA. IL-6 regulation on skeletal muscle mitochondrial remodeling during cancer cachexia in the ApcMin/+ mouse. Skelet Muscle 2: 14, 2012. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White JP, Reecy JM, Washington TA, Sato S, Le ME, Davis JM, Wilson LB, Carson JA. Overload-induced skeletal muscle extracellular matrix remodelling and myofibre growth in mice lacking IL-6. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 197: 321–332, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wojewoda M, Kmiecik K, Majerczak J, Ventura-Clapier R, Fortin D, Onopiuk M, Rog J, Kaminski K, Chlopicki S, Zoladz JA. Skeletal muscle response to endurance training in IL-6−/− mice. Int J Sports Med 36: 1163–1169, 2015. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1555851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wojewoda M, Kmiecik K, Ventura-Clapier R, Fortin D, Onopiuk M, Jakubczyk J, Sitek B, Fedorowicz A, Majerczak J, Kaminski K, Chlopicki S, Zoladz JA. Running performance at high running velocities is impaired but V′O2max and peripheral endothelial function are preserved in IL-6−/− mice. PLoS One 9: e88333, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yan Z, Lira VA, Greene NP. Exercise training-induced regulation of mitochondrial quality. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 40: 159–164, 2012. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3182575599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang L, Pan J, Dong Y, Tweardy DJ, Dong Y, Garibotto G, Mitch WE. Stat3 activation links a C/EBPδ to myostatin pathway to stimulate loss of muscle mass. Cell Metab 18: 368–379, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All protocols used and data generated from this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.