Abstract

Hindbrain catecholamine neurons convey gut-derived metabolic signals to an interconnected neuronal network in the hypothalamus and adjacent forebrain. These neurons are critical for short-term glycemic control, glucocorticoid and glucoprivic feeding responses, and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) signaling. Here we investigate whether these pathways also contribute to long-term energy homeostasis by controlling obesogenic sensitivity to a high-fat/high-sucrose choice (HFSC) diet. We ablated hindbrain-originating catecholaminergic projections by injecting anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-conjugated saporin (DSAP) into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) of male rats fed a chow diet for up to 12 wk or a HFSC diet for 8 wk. We measured the effects of DSAP lesions on food choices; visceral adiposity; plasma glucose, insulin, and leptin; and indicators of long-term ACTH and corticosterone secretion. We also determined lesion effects on the number of carbohydrate or fat calories required to increase visceral fat. Finally, we examined corticotropin-releasing hormone levels in the PVH and arcuate nucleus expression of neuropeptide Y (Npy), agouti-related peptide (Agrp), and proopiomelanocortin (Pomc). DSAP-injected chow-fed rats slowly increase visceral adiposity but quickly develop mild insulin resistance and elevated blood glucose. DSAP-injected HFSC-fed rats, however, dramatically increase food intake, body weight, and visceral adiposity beyond the level in control HFSC-fed rats. These changes are concomitant with 1) a reduction in the number of carbohydrate calories required to generate visceral fat, 2) abnormal Npy, Agrp, and Pomc expression, and 3) aberrant control of insulin secretion and glucocorticoid negative feedback. Long-term metabolic adaptations to high-carbohydrate diets, therefore, require intact forebrain catecholamine projections. Without them, animals cannot alter forebrain mechanisms to restrain increased visceral adiposity.

Keywords: arcuate nucleus, food efficiency, glucocorticoids, hindbrain, hypothalamus, paraventricular nucleus

INTRODUCTION

High-fat/high-sucrose choice (HFSC) diets are widely used in rodent studies as analogs of Western diets to study interactions between diet and the neural mechanisms that lead to obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Rats given an unrestricted intake choice between a high-fat food source, regular chow, and a 30% sucrose solution quickly begin to overconsume the high-calorie sources, particularly as a consequence of an increased motivation to consume sucrose (29). This leads to increased abdominal adiposity and dysregulated glycemic control.

Significant advances in understanding the brain mechanisms that lead to diet-induced obesity (DIO) have come from the pioneering work of Levin and colleagues. They showed that when male Sprague-Dawley rats are given a high-calorie diet, some animals become hyperphagic and obese (diet-sensitive), while others maintain their calorie intake at control levels and are resistant to the obesogenic effects of the diet (diet-resistant) (33). Although the brain mechanisms responsible for this heterogeneity remain unclear, a consistent finding is a disruption to hypothalamic catecholaminergic signaling in diet-sensitive, but not diet-resistant, rats (31, 32, 37). These results implicate a major role for the hindbrain catecholaminergic neurons that innervate the hypothalamus in regulation of metabolic responses to obesogenic high-calorie diets. These neurons are, therefore, well placed to provide the hypothalamus with information about vagally and spinally conveyed sensory signals from, for example, the gut, hepatic portal vein, liver, and adipose tissue. Hypothalamic neurons can then integrate this information with circulating signals such as leptin, insulin, and nutrients to enable full adaptive metabolic control when animals are presented with challenges to energy balance.

Two groups of catecholaminergic neurons provide robust innervation to an interconnected set of forebrain targets, including the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH), dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH), and arcuate nucleus (ARH). One group is located in the ventrolateral (VLM; A1 and C1) and the other in the dorsomedial (A2 and C2) medulla (9, 10, 53). A1 and C1 VLM neurons are intimately involved with driving rapid responses to physiological challenges (17, 18, 49, 53). In this way, these hindbrain catecholaminergic projections collectively mediate a broad range of feeding and adrenal counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia, cytoglucopenia, cholecystokinin, and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor stimulation (12, 21, 25, 26, 30, 46, 47, 50).

In contrast to short-term responses, the role of forebrain-projecting catecholaminergic neurons in long-term metabolic control, including the development of DIO, has not been investigated. In the present study we use male rats and an immunotoxin [anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH)-conjugated saporin (DSAP)] targeted to the PVH. DSAP specifically ablates those DBH-containing neurons that project from the hindbrain to the PVH. Because these neurons are highly collateralized, their terminal fields in other forebrain regions are also ablated. This means that, rather than exclusively removing catecholamine inputs to the PVH, DSAP removes inputs to an interconnected forebrain network that includes the PVH (3, 27, 48, 54). DSAP is highly specific, in that it leaves all resident neurons and other connections in these target areas intact and fully functional (21, 25, 30, 50). We then determine how ablation of these neurons affects the development of DIO in rats maintained on a HFSC diet consisting of food pellets containing 60% calories as fat, a 30% sucrose solution, and chow. Our hypothesis is that if catecholaminergic signaling to this DSAP-defined forebrain network is a major determinant of DIO sensitivity, then ablation of these neurons should exacerbate HFSC DIO and associated metabolic maladaptations in DSAP-lesioned animals compared with intact controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany) or Harlan (Envigo). They were singly caged in climate-controlled (21–23°C) rooms and maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with unlimited access to tap water and diets. Animals were maintained on a continuous chow diet [diet 3436 (Provimi Kliba, Kaiseraugust, Switzerland) or Teklad rodent diet 8604 (Envigo)] or a HFSC diet consisting of D12492 (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ), chow diet 8604, and a 30% (wt/vol) sucrose solution. The nutritional and calorie composition of the diets was as follows: 4.5% fat, 18.5% protein, 54% carbohydrate, and 3.85 kcal/g energy density (diet 3436); 4.7% fat, 24.3% protein, 40.2% carbohydrate, and 3.00 kcal/g energy density (diet 8604); and 60% fat, 20% protein, 20% carbohydrate (as maltodextrin 10 and sucrose), and 5.24 kcal/g energy density (D12492).

All procedures were approved by the Canton of Zürich Veterinary Office or the University of Southern California (USC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Lesions

Catecholaminergic projections to the PVH and related parts of the forebrain were lesioned as previously described (21, 25, 30). Briefly, bilateral injections, each consisting of 42 ng/200 nl DSAP or equimolar amounts of control mouse IgG-saporin conjugate (MSAP; Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA), were made with stereotaxic guidance into the PVH under ketamine-xylazine or isoflurane anesthesia. Each injection was made using a glass capillary micropipette connected with polyethylene tubing to a microinjector (Picospritzer III, Parker Hannifin, Hollis, NH). To ensure full development of the lesion, experimental manipulations did not begin until ≥14 days after surgery (50); the end of this period was designated day 0 for each group of animals. The diet change for the HFSC diet-fed animals was made at this time (day 0).

Experimental Design

Two groups of rats [n = 13 animals, 380 g target body wt at surgery (ETH Zürich); n = 27 animals, 300 g target body wt at surgery (USC)] were each injected with MSAP (n = 19) or DSAP (n = 21) into the PVH and allowed unlimited access to the 3436 or 8604 chow diet and water for up to 12 wk. A third group [n = 13 animals, 300 g target body wt at surgery (USC)] was also injected with control MSAP (n = 8) or DSAP (n = 5) and then maintained from day 0 on the HFSC diet and water for 8 wk. The study was designed so that the ETH Zürich procedures involved only DSAP- and MSAP-injected chow-fed animals, while the USC procedures involved DSAP- and MSAP-injected HFSC-fed animals and the corresponding chow-fed controls. Sprague-Dawley rats and the same lesion protocol were used for both sets of experiments.

A series of tests (calorie intake from carbohydrate, fat, and protein; fasting glucose homeostasis; visceral fat pad weight; hormone analysis; measures of glucocorticoid activity; and hypothalamic neuropeptide mRNA levels) were performed to determine the effect of the loss of forebrain catecholaminergic inputs on various energy metabolism-related end points when animals consume a low-fat chow diet and when they are offered a HFSC diet. Each test was performed on an appropriate starting body weight-matched cohort of MSAP- and DSAP-injected animals. Not all animals within each treatment group were used for all tests.

Glucose Homeostasis

Chow-fed animals were overnight-fasted on day 16 or 46, and tail blood samples were obtained for glucose and insulin determinations. The homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated from the rat-specific formula of Cacho et al. (7): HOMA-IR = fasting plasma glucose (mM) × fasting plasma insulin (µU/ml)/24.3. Venous blood samples for nonfasting glucose determinations were obtained from HFSC diet-fed animals and their chow-fed controls immediately before perfusion (see Perfusion and histology).

Calorie Intake

The total 24-h intake of each calorie source was measured in groups of MSAP- and DSAP-injected animals fed chow (8604) or HFSC for 6 days starting on day 50. These data were used to calculate total calorie intake and calorie intake from fat, protein, total carbohydrate, and sucrose alone and food efficiency [body wt gain (g)/kcal intake] during that time (34, 43). The calorie content of each diet source was derived from manufacturer specifications.

Analytical Methods

Perfusion and histology.

At the end of the experiments, all animals were anesthetized with isoflurane 3–4 h after lights-on. For animals maintained on the HFSC diet and their chow-fed controls, single 1-ml blood samples were quickly taken from the external jugular vein for plasma leptin, glucose, and insulin determinations. Animals were immediately perfused transcardially with buffered 4% paraformaldehyde, and brains were removed from the skull and postfixed as previously described (21, 30). Brains were frozen with dry ice and stored at −80°C until they were processed for immunohistochemistry and, for some animals, in situ hybridization (ISH).

After the brain was removed, the following tissues were dissected from perfused animals, blotted dry, and weighed: thymus gland, both adrenal glands (combined weights), the bilateral retroperitoneal/perirenal fat pad, and the adipose tissue adhering to the mesenteric, superior mesenteric, and hepatic portal veins, which together were designated mesenteric fat. Serial 1:8 30-µm frozen coronal sections were cut through the hypothalamus and hindbrain and either saved in cryoprotectant (for immunohistochemistry) or immediately mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (for ISH), as previously described (67). One series from each animal was stained with thionin for determination of local cytoarchitectonics.

DBH immunohistochemistry.

The extent of the lesions was assessed by examination of loss of DBH-immunoreactive (ir) fibers in the PVH as well as loss of DBH-ir cell bodies in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and the VLM. Sections containing the hypothalamus and hindbrains of all MSAP- and DSAP-injected animals were stained using an antibody against DBH (1:10,000 dilution, mouse anti-DBH; catalog no. MAB308, Millipore, Temecula, CA). Specific staining was visualized using a streptavidin-HRP-diaminobenzidine chromagen or Cy3 immunofluorescence, as previously described (21, 25, 30). Only animals with a bilateral loss of ≥80% of DBH fibers in the PVH were included in the analysis. Briefly, the mean area of each PVH that was occupied by DBH-ir fibers in MSAP-injected animals was measured and designated 100% innervation. The mean area occupied by DBH-ir fibers in each DSAP-injected animal was similarly measured. A complete lesion was assigned if this value was ≤20% of the mean MSAP value for both PVH of an animal [see Khan et al. (25) for more details].

Corticotropin-releasing hormone immunohistochemistry and image analysis.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)-ir in the PVH was assessed using a well-characterized rabbit polyclonal CRH antibody [C-70 (24)] and the mouse monoclonal DBH antibody described above. Specific staining was visualized in sections containing the PVH using appropriate Cy3- and Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibodies and then imaged using previously described two-channel confocal methods (25, 27). The specific mean gray level (MGL) of the CRH-ir in the PVH was quantified as previously described (25, 27).

In situ hybridization.

Sections for the ISH analyses were prepared as previously described (67). Neuropeptide Y (NPY), agouti-related peptide (AgRP), and proopiomelanocortin (POMC) mRNA levels in the ARH and the posterior part of the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus were detected by radioisotopic (35S) ISH using cRNA probes [NPY (65), AgRP (62), and POMC (65)], as previously described (67).

MGLs of the RNA hybridization signals in the ARH and DMH were measured from images acquired from Agfa Mamoray HDR-C X-ray film and iVision imaging software (v4.5, BioVision Technologies, Exton, PA). Signal quantitation is described elsewhere (66, 67), except the MGL was calculated on a signal segmented at 2× SD above the mean background value. Hybridization signal values were expressed on a 0–255 gray scale after subtraction of background values.

Blood/plasma assays.

Plasma glucose was measured using an AccuChek (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) or an AlphaTrak (Abbott Laboratories) glucose meter with no. 7 test strips calibrated for rats. Insulin was measured using an immunoassay [single spot for mouse/rat (catalog no. K152BZC, Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD)] or a rat insulin ELISA (Alpco, Salem, NH), which had a lower detection limit of 4 µU/ml (140 pg/ml). Plasma leptin concentrations were measured with a double-antibody 125I-labeled antigen radioimmunoassay (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) that had a lower sensitivity limit of 0.5 ng/ml. All samples were run in a single assay.

CT scans for analysis of body composition.

Body composition was analyzed 12 wk after the beginning of the experiment (day 0) using a computerized tomography system (La Theta LCT-100, Aloka) with previously validated methodology (19). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed supine in a cylindrical holder (120 mm inner diameter). An initial whole body sagittal image was obtained to ensure proper placement of the animal. Scans were made from vertebrae L1–L6 with a 2-mm pitch. Volumes of adipose tissue (fat mass), bone, air, and the remainder (lean mass) were detected by the Aloka software based on their X-ray absorption. Fat mass and lean mass were computed using the density factors 0.92 and 1.10 g/cm3, respectively.

Statistics

Statistical significance between group means was determined by one-way ANOVA, Student’s t-test, or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test or Student’s t-test where appropriate using GraphPad Prism (version 6.05 for Windows) or JMP Pro 12 (Mac OS). Regression analyses, outlier exclusion (Cook’s distance >1), and slope comparisons (analysis of covariance) were performed using JMP Pro 12 (SAS Institute) and Microsoft Excel. Statistical analyses were restricted to comparisons within experiments performed at ETH Zürich or USC.

RESULTS

DSAP Injected Into the PVH Denervates Catecholaminergic Projections to the Mediobasal Hypothalamus

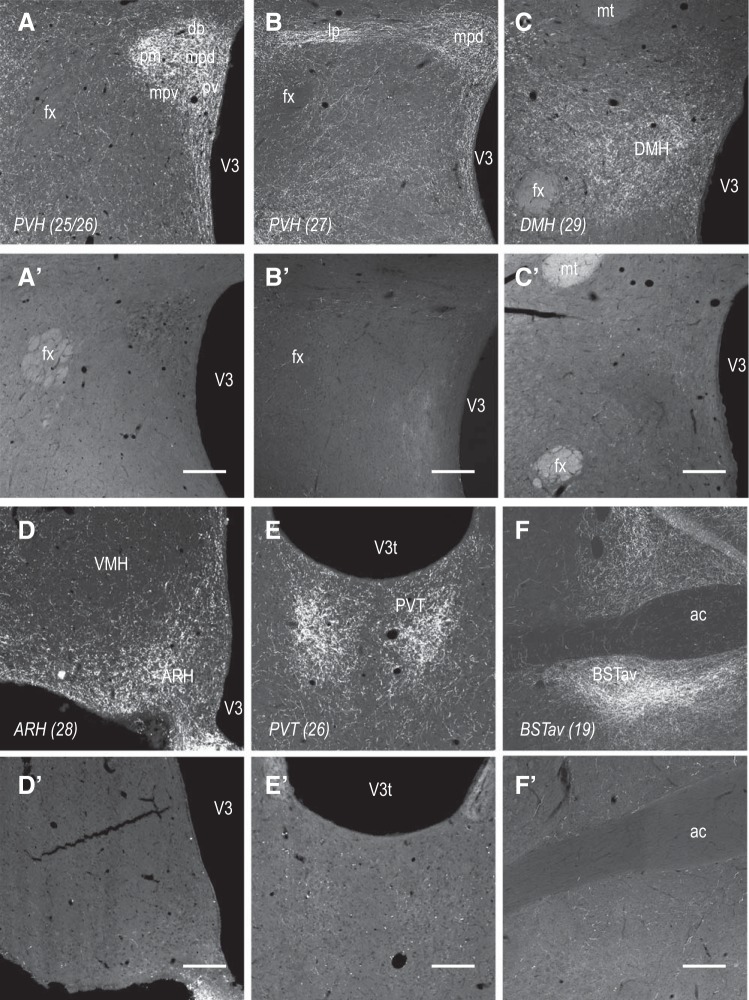

Figure 1 shows effects of MSAP and DSAP injections into the PVH on DBH-ir fibers in various forebrain regions. Because of extensive collateralization, when DSAP is delivered to a single target, in this case, the PVH, there is also an almost complete loss of DBH-ir fibers in the DMH, ARH, PVT, and anteroventral part of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTav), as well as parts of the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) (data not shown), as reported previously. As we and others have described elsewhere (3, 6, 21, 30, 48), these lesions primarily result in significant loss of DBH-ir neurons in the VLM and in the more caudal parts of the NTS.

Fig. 1.

Anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH)-conjugated saporin (DSAP) injected into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) denervates catecholaminergic projections to the mediobasal hypothalamus. Bilateral injections of DSAP (A′–F′), but not mouse IgG-saporin conjugate (MSAP; A–F), into the PVH eliminate catecholaminergic innervation in all parts of the PVH (A, B, A′, and B′), dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH; C and C′), arcuate nucleus (ARH; D and D′), paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT; E and E′), and anteroventral part of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTav; F and F′). Photomicrographs show coronal sections through each of these regions immunohistochemically stained with an anti-DBH mouse monoclonal antibody and visualized using a Alexa 488-labeled secondary antibody. Numbers in parentheses indicate rat atlas level of Swanson (58). Medial is to the right for all panels. Scale bars = 200 μm, except for D and D′, where scale bar = 100 μm. Abbreviations: ac, anterior commissure; dp, PVH dorsal parvicellular part; fx, fornix; lp, PVH lateral parvicellular part; mpd, PVH dorsal zone of the medial parvicellular part; mpv, PVH ventral zone of the medial parvicellular part; mt, mammilothalamic tract; pm, PVH posterior magnocellular part; pv, PVH periventricular part; V3, 3rd ventricle; V3t, 3rd ventricle, thalamic part; VMH, ventromedial nucleus.

DSAP Increases HFSC-Induced Body Weight Gain

All animals lost some body weight immediately after surgery but recovered their presurgery weights within 2–3 days. Thereafter, they very quickly gained weight, with no difference between MSAP- and DSAP-lesioned animals at day 0. Table 1 shows that, for MSAP- and DSAP-lesioned animals maintained on the chow diet for 8 wk from day 0 (MSAP-chow and DSAP-chow), there were no significant differences in either starting and terminal body weights or percent change in body weight. MSAP- and DSAP-lesioned animals fed the HFSC diet (MSAP-HFSC and DSAP-HFSC) had significantly increased body weights at the end of the experiment compared with the corresponding MSAP-chow and DSAP-chow animals. DSAP-HFSC animals were significantly heavier than MSAP-HFSC animals.

Table 1.

DSAP increases HFSC-induced body weight gain

| Body Weight, g |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Surgery | Diet change | Terminal | %Change From Diet Change | |

| Chow | |||||

| MSAP | 5 | 292 ± 6 | 338 ± 6 | 434 ± 7 | 28.4 ± 1.7 |

| DSAP | 9 | 295 ± 2 | 351 ± 7 | 461 ± 8 | 31.5 ± 1.3 |

| HFSC | |||||

| MSAP | 8 | 299 ± 4 | 350 ± 7 | 493 ± 13† | 40.9 ± 2.0 |

| DSAP | 5 | 308 ± 4 | 367 ± 3 | 625 ± 29*‡ | 69.1 ± 8.8 |

Values are means ± SE (n = number of animals) of body weight at surgery, diet change (day 0), and termination in animals injected with mouse IgG-saporin conjugate (MSAP) or anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-conjugated saporin (DSAP) into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and then fed chow or a high-fat/high-sucrose choice (HFSC) diet for 56 days.

P < 0.02 vs. MSAP-chow;

P < 0.0002 vs. DSAP-chow;

P < 0.01 vs. MSAP-HFSC.

DSAP Increases HFSC Total Calorie Intake and Blunts Adaptations in Food Efficiency

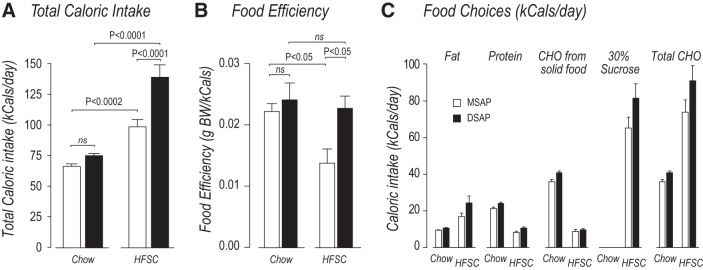

DSAP had no significant effect on the mean daily calorie intake of animals maintained on a chow-only diet (Fig. 2A). However, significantly more calories were consumed by DSAP-HFSC than MSAP-HFSC animals (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-conjugated saporin (DSAP) increases high-fat/high-sucrose choice (HFSC) total calorie intake and blunts adaptations in food efficiency. A–C: effects of mouse IgG-saporin conjugate (MSAP; open bars) and DSAP (solid bars) injections on total daily calorie intake, food efficiency, and food component choices on days 50–55 for animals fed chow or HFSC diet. A: DSAP had no effect on total chow calorie intake compared with MSAP animals. DSAP-HFSC animals increased their calorie intake compared with MSAP-HFSC animals. B: MSAP-HFSC animals reduced their food efficiency compared with MSAP-chow animals, whereas DSAP-HFSC animals did not reduce their food efficiency compared with DSAP-chow animals. C: DSAP lesions had no effect on food component choices made by HFSC animals. CHO, carbohydrate; ns, not significant. Values are means ± SE; n = 5 MSAP-chow and DSAP-HFSC and n = 8 DSAP-chow and MSAP-HFSC.

Figure 2B shows that DSAP and MSAP animals used the same number of calories to increase body weight when each group ate the chow-only diet (food efficiency). MSAP-HFSC animals adapted in a way that significantly reduced their body weight increases per kilocalorie eaten. However, this adaptation did not occur in DSAP animals, which used the same number of kilocalories per gram of body weight increase when they consumed the HFSC and the chow-only diet.

When MSAP and DSAP animals were given the HFSC diet, both groups obtained ~65% of their total calories from the 30% sucrose solution, 25% from the high-fat pellets, and 10% from chow. This meant that they obtained ~20% more of their total calories from all carbohydrate sources than those eating the chow diet (Fig. 2C). Despite the opportunity for animals given the HFSC diet to eat the high-fat pellets, they increased the percentage of fat in their total calorie intake by only ~5% compared with chow-fed animals (Fig. 2C). Within each calorie source, there were no significant differences between the calorie intakes of MSAP and DSAP animals (Fig. 2C); that is, the absence of catecholaminergic projections did not alter the animals’ preference for a particular calorie source.

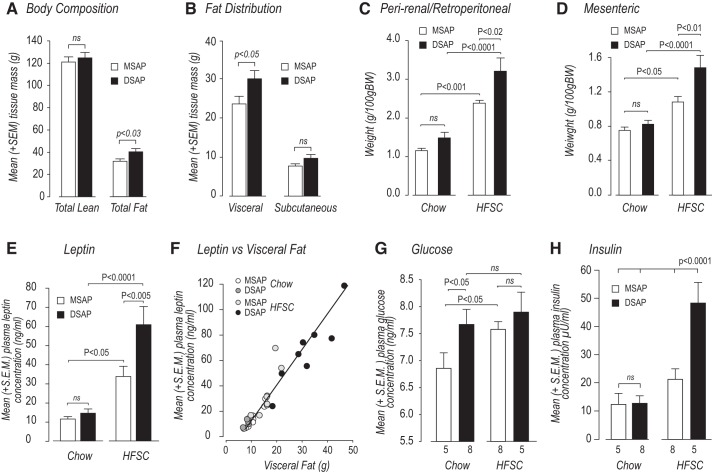

DSAP Alters Body Composition and Fat Distribution With Chow and HFSC Feeding

Figure 3A shows that DSAP had no significant effect on lean body mass of chow-fed animals 12 wk after the start of the experiment. However, total fat mass was significantly greater in DSAP-chow than MSAP-chow animals (Fig. 3A). The increased adipose tissue mass in DSAP animals was accounted for by a significant increase in visceral, rather than subcutaneous, fat, which was unaffected by DSAP (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-conjugated saporin (DSAP) increases adiposity with high-fat/high-sucrose choice (HFSC) diet and alters glucose homeostasis with chow and HFSC. A and B: effects of mouse IgG-saporin conjugate (MSAP) and DSAP injections on body composition and fat distribution of animals fed chow diet for 84 days. C–E: weight of perirenal/retroperitoneal and mesenteric fat and plasma leptin concentrations of animals fed chow or HFSC diet for 56 days. Although the weight of visceral fat pads was increased with the HFSC diet, it was significantly greater in DSAP-HFSC than MSAP-HFSC animals. F: plasma leptin concentrations were tightly correlated with total weight of visceral (perirenal/retroperitoneal + mesenteric) fat (y = 2.5615x – 10.934, R2 = 0.91, F = 283.5, df 1,11, P < 0.0001). G and H: plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in MSAP and DSAP animals fed chow or HFSC diet at 56 days. Values are means ± SE; n = 5 MSAP-chow and DSAP-HFSC and n = 8 DSAP-chow and MSAP-HFSC. ns, Not significant.

After the animals had received the HFSC diet for 8 wk, we measured the effects of DSAP on the weight of two visceral fat locations: perirenal/retroperitoneal fat and mesenteric fat (i.e., fat adhering to the mesenteric, superior mesenteric, and hepatic portal veins). These two locations collectively were designated visceral fat. MSAP-HFSC and DSAP-HFSC animals had significantly more fat in both locations than MSAP-chow and DSAP-chow animals, respectively (Fig. 3, C and D). Although DSAP had no significant effect on visceral fat accumulation in animals maintained on chow, significantly more fat was found in both locations in DSAP-HFSC than MSAP-HFSC animals. It is also notable that DSAP-chow animals accumulate significantly more visceral fat than MSAP-chow animals when measured at 12 wk (Fig. 3B). Similarly, leptin concentrations were significantly higher in DSAP-HFSC than MSAP-HFSC animals (Fig. 3E). Leptin concentrations were tightly correlated with visceral adiposity for all MSAP and DSAP animals, irrespective of their diet (Fig. 3F).

DSAP Alters Glucose Homeostasis With Chow and HFSC Feeding

Although DSAP did not alter fasting plasma glucose concentrations in chow-fed animals on day 16, it significantly increased fasting plasma insulin concentrations and the HOMA-IR, indicating mild insulin resistance at this time (Table 2). On day 46, fasting plasma insulin, glucose, and the HOMA-IR were significantly increased in DSAP-chow animals (Table 2). At termination (day 56), plasma glucose concentrations were significantly higher in DSAP-chow animals, but surprisingly not DSAP-HFSC animals, than in their intact controls (Fig. 3G). However, DSAP-HFSC animals showed severe hyperinsulinemia compared with all other groups (Fig. 3H).

Table 2.

DSAP alters glucose homeostasis with chow feeding

| MSAP | DSAP | %MSAP | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 16 | ||||

| Glucose, mM | 5.62 ± 0.18 | 6.00 ± 0.26 | 107.1 ± 5.5 | NS |

| Insulin, µU/ml | 8.95 ± 1.02 | 16.89 ± 2.96 | 188.8 ± 13.1 | <0.05 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.087 ± 0.298 | 4.131 ± 0.670 | 197.9 ± 32.1 | <0.05 |

| n | 6 | 7 | ||

| Day 46 | ||||

| Glucose, mM | 5.76 ± 0.17 | 6.46 ± 0.07 | 112.2 ± 1.3 | <0.02 |

| Insulin, µU/ml | 5.39 ± 0.65 | 11.99 ± 2.44 | 229.8 ± 44.0 | <0.05 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.287 ± 0.182 | 3.286 ± 0.610 | 255.3 ± 47.4 | <0.05 |

| n | 4 | 5 | ||

Values are means ± SE (n = number of animals) of fasting plasma glucose and insulin in animals injected with mouse IgG-saporin conjugate (MSAP) or anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-conjugated saporin (DSAP) into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and then fed a chow diet for 16 or 46 days. Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated according to Cacho et al. (7). NS, not significant.

DSAP Decreases the Number of Carbohydrate- But Not Fat-Derived Calories Needed to Increase Visceral Fat Mass With Chow and HFSC Feeding

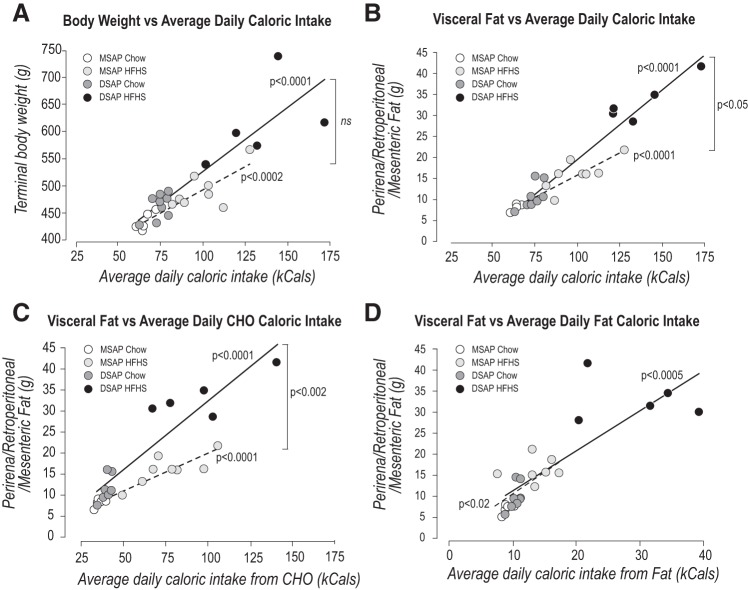

To determine how the absence of forebrain catecholaminergic projections affected the degree to which calorie intake increases body weight and visceral adiposity, we examined the relationships between these two dependent variables and 1) the average daily calorie intake during the 6 days immediately preceding termination and 2) the average calorie intake of carbohydrate or fat during the same period in animals fed the chow or HFSC diet.

We found significant positive correlations between average daily calorie intake and terminal body weight (Fig. 4A) in MSAP and DSAP animals but no significant difference between the slopes of the two regression lines. We also found significant positive correlations between average daily calorie intake and the terminal weight of visceral fat (Fig. 4B) in MSAP and DSAP animals. For these variables, there was a significant difference between the slopes of the two regression lines.

Fig. 4.

Anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-conjugated saporin (DSAP) alters distribution of carbohydrate, but not fat, calories. A: average daily calorie intake and terminal body weight were significantly correlated in mouse IgG-saporin conjugate (MSAP; dashed line; y = 1.698x + 321.84, R2 = 0.741, F = 31.43, df 1,11, P < 0.0002, n = 12) and DSAP (solid line; y = 2.352x + 290.37, R2 = 0.790, F = 49.02, df 1,11, P < 0.0001, n = 12) animals. Slopes of the two regression lines were not significantly different. B: average daily calorie intake and visceral fat mass were significantly correlated in MSAP (dashed line; y = 1.70x + 321.84, R2 = 0.741, F = 31.43, df 1,11, P < 0.0002, n = 12) and DSAP (solid line; y = 2.352x + 290.37, R2 = 790, F = 49.02, df 1,11, P < 0.0001, n = 12) animals. Slopes of the two regression lines were significantly different (P < 0.05). C: average daily intake of total carbohydrate (CHO) and visceral fat mass were tightly correlated in MSAP (dashed line; y = 0.03x + 2.18, R2 = 0.852, F = 63.34, df 1,11, P < 0.0001, n = 12) and DSAP (solid line; y = 0.056x − 1.24, R2 = 0.861, F = 67.98, df 1,11, P < 0.0001, n = 12) animals. Slopes of the two regression lines were significantly different (P < 0.002). D: average daily fat intake and terminal weight of visceral fat were significantly correlated in MSAP (dashed line; y = 1.018x + 1.199, R2 = 0.456, F = 8.41, df 1,10, P < 0.02, n = 11) and DSAP (solid line; y = 0.153x + 3.197, R2 = 0.688; F = 24.28, df 1,11, P < 0.0005. n = 12) animals. Slopes of the two regression lines were not significantly different. ns, Not significant.

When we examined which diet components were responsible for these correlations, we found highly significant correlations between the terminal weight of visceral fat and average daily total carbohydrate calorie intake (Fig. 4C) in MSAP and DSAP animals. Furthermore, there was a significant difference between the slopes of the two regression lines. However, this was not the case with the average daily fat calorie intake. While there were significant correlations between the terminal weight of visceral fat and the average daily fat intake in MSAP and DSAP animals, the two regression lines were not significantly different (Fig. 4D).

DSAP Produces Glucocorticoid Resistance in the PVH of HFSC-Fed Animals

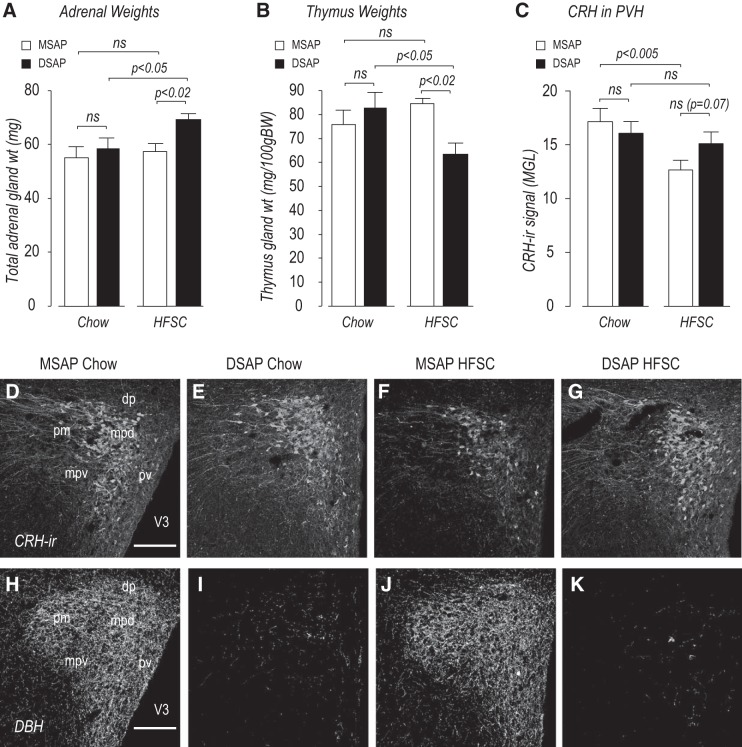

Because of pronounced episodic and daily excursions in corticosterone secretion (65, 66), single blood samples do not have sufficient temporal resolution to determine long-term changes in the glucocorticoid environment (59). We therefore examined the effects of DSAP on adrenal and thymus weights (Fig. 5, A and B), which respond to changes in ACTH and circulating corticosterone, respectively, over extended periods (1, 42, 68). We also examined PVH CRH-ir in these same animals.

Fig. 5.

Anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH)-conjugated saporin (DSAP) produces glucocorticoid resistance in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) of high-fat/high-sucrose choice (HFSC)-fed animals. A–G: combined adrenal weights (A), thymus weights (B), and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) immunoreactivity (ir) in the PVH (C and D–G) in mouse IgG-saporin conjugate (MSAP) and DSAP animals given chow or a HFSC diet for 56 days. MGL, mean gray level. H–K: DBH immunoreactivity in the same sections stained for CRH immunoreactivity (D–G) in MSAP (H and J) and DSAP (E and G) animals. Scale bars = 150 μm. dp, PVH dorsal parvicellular part; mpd, PVH dorsal zone of the medial parvicellular part; mpv, PVH ventral zone of the medial parvicellular part; pm, PVH posterior magnocellular part; pv, PVH periventricular part; V3, 3rd ventricle. Values are means ± SE; n = 5 MSAP-chow and DSAP-HFSC and n = 8 DSAP-chow and MSAP-HFSC. ns, Not significant.

Only in DSAP-HFSC animals were adrenal weights significantly increased, while thymus weights were significantly decreased; both findings are consistent with an elevated activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis over an extended time. PVH CRH-ir was unchanged in MSAP-chow and DSAP-chow animals (Fig. 5, C–E) but was significantly reduced in MSAP-HFSC compared with MSAP-chow animals (Fig. 5, C, D, and F). This reduction did not occur in DSAP-HFSC animals (Fig. 5, C, E, and G).

DSAP Alters Hypothalamic AgRP, POMC, and NPY mRNA Levels With HFSC Feeding

We measured NPY (Fig. 6, A and E), AgRP (Fig. 6, B and F), and POMC (Fig. 6, C and G) mRNA levels in the ARH and NPY mRNA levels in the DMH (Fig. 6, D and H). There were significant effects of the lesion and diet on all three mRNAs in the ARH, but not NPY mRNA in the DMH. ARH NPY mRNA levels were lower in MSAP-HFSC than MSAP-chow animals (Fig. 6, A and E). DSAP, however, reversed the decrease in MSAP-HFSC animals, so that their NPY mRNA level was indistinguishable from that in DSAP-chow animals (Fig. 6, A and E). Conversely, AgRP mRNA was not significantly different in any treatment group except DSAP-HFSC animals (Fig. 6, B and F), in which levels were significantly lower than in the other groups. POMC mRNA levels were not affected in DSAP-chow animals but were increased in DSAP-HFSC compared with MSAP-HFSC animals (Fig. 6, C and G).

Fig. 6.

Anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-conjugated saporin (DSAP) alters hypothalamic agouti-related peptide (AgRP), proopiomelanocortin (POMC), and neuropeptide Y (NPY) mRNA levels with high-fat/high-sucrose choice (HFSC) feeding. A–C and E–G: effects of mouse IgG-saporin conjugate (MSAP) and DSAP injections on levels of NPY (A and E), AgRP (B and F), and POMC (C and G) in the arcuate nucleus (ARH). D and H: NPY mRNA levels in the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH). Values are means ± SE; n = 5 MSAP-chow and DSAP-HFSC and n = 8 DSAP-chow and MSAP-HFSC for ARH NPY and POMC mRNAs; n = 4 MSAP-chow and DSAP-HFSC and n = 8 DSAP-chow and MSAP-HFSC for ARH AgRP mRNA; n = 4 MSAP-chow and DSAP-HFSC, n = 6 DSAP chow, and n = 7 MSAP-HFSC for DMH NPY mRNA. ns, Not significant.

DISCUSSION

Hypothalamic neurons control energy metabolism by integrating the metabolic information conveyed by two sets of inputs: 1) endocrine and nutrient signals circulating in the blood and 2) ascending projections from the hindbrain that communicate metabolic signals from the gut, adipose tissue, and liver that arrive via spinal and vagal afferents. While the impact of circulating factors on the ability of hypothalamic neurons to control energy metabolism and obesity is extremely well documented, how ascending projections contribute is unknown.

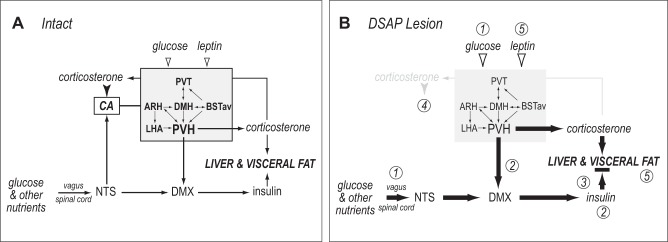

The projections of catecholaminergic neurons are part of this ascending system and are strongly implicated in the short-term control of food intake and energy expenditure (23, 30, 38, 49). The extensive collateralization of these neurons means that their effective forebrain target is a highly interconnected and interactive network, rather than a single target. This network (Fig. 7) is defined by its sensitivity to DSAP and comprises the PVH, DMH, ARH, PVT, BSTav, and parts of the LHA (3, 13, 27, 48, 54, 61, 69). Because of its extensive descending connections (16), the PVH is most likely its primary output to autonomic control systems in the hindbrain (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effects of anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-conjugated saporin (DSAP) lesion. A: in intact animals, hindbrain catecholaminergic neurons (CA) receive vagally and spinally conveyed information about glucose and other nutrients in the gut and hepatic portal vein by way of projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). Catecholaminergic projections provide collaterals to a set of highly interconnected forebrain nuclei (gray box), which also transduces information about circulating glucose and leptin levels (open arrowheads). The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) is the principal output from this network. It controls adrenocortical corticosterone secretion and, by way of projections to the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMX), β-cell insulin secretion. Corticosterone negative-feedback signals (solid arrowhead) are relayed to corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) neurons in the PVH by catecholaminergic projections. B: DSAP injections into the PVH remove catecholaminergic projections to all components in the forebrain network. Loss of these inputs has the following effects: increased glycemia (1), increased circulating insulin, possibly mediated by reduced inhibition from PVH to the DMX (2), insulin resistance (black horizontal bar) (3), and loss of negative-feedback signals from elevated circulating corticosterone to CRH neurons in the PVH (4). When DSAP animals are fed the high-fat/high-sucrose choice diet, the combination of effects 1–4 is exacerbated, leading to increased visceral adiposity and increased circulating leptin (5). ARH, arcuate nucleus; BSTav, anteroventral part of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; DMH, dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; PVT, paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus.

We now show that the loss of these projections in DSAP-lesioned animals maintained on a HFSC diet for up to 8 wk dramatically exacerbates weight gain and visceral adiposity compared with MSAP-HFSC animals. The increased adiposity in DSAP-lesioned animals is strongly associated with their inability to adapt their carbohydrate metabolism to the HFSC diet. This leads to significantly more visceral fat accumulation per kilocalorie of consumed carbohydrate in DSAP- than MSAP-lesioned animals.

Dysfunction in Chow-Fed Animals

To understand the neural mechanisms responsible for these effects, it is useful to examine how they develop in chow-fed animals. We previously reported three energy balance-related changes that occur soon after DSAP lesioning becomes effective: 1) a slowing of gastric emptying, 2) an impaired ability of moderately elevated levels of corticosterone to decrease food intake, body weight, and PVH Crh expression, and 3) increased basal activation of ARH POMC neurons and increased PVH α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone immunoreactivity (23, 27, 30). We now show that insulin resistance also develops during this same period and before any detectable increases in visceral adiposity, which occurs much later. Early-onset hyperinsulinemia stands out as a compelling mediator for some of the subsequent metabolic dysfunctions we observe in DSAP-HFSC animals, particularly as hyperinsulinemia is associated with increased glucose uptake and lipogenesis in adipocytes (41, 55, 60).

We previously showed that catecholaminergic neurons relay essential glucosensory information from the hindbrain and hepatic portal vein to this DSAP-defined forebrain network that drives adrenal responses to insulin-induced hypoglycemia (21, 25, 50). Therefore, a potential effector mechanism for the early-onset hyperinsulinemia we see in DSAP-chow animals is the disruption to a glucose-dependent negative-feedback signal mediated by catecholaminergic projections that normally restrains insulin secretion (20). However, in DSAP-lesioned animals, this negative feedback is absent, meaning that forebrain-mediated stimulation of insulin secretion persists longer than in MSAP-lesioned animals. Because HFSC-fed animals show dramatic increases in carbohydrate intake compared with chow-fed animals, the effects of losing feedback control are subsequently amplified in DSAP-HFSC rats. The idea that PVH neurons can moderate autonomic outflow when energy balance is altered is supported by a recent report showing that PVH preautonomic neurons that influence liver metabolism increase their firing rates in obese db/db mice compared with lean controls (15).

It seems likely that early-onset hyperinsulinemia, elevated blood glucose, and increasing insulin resistance each contribute to the eventual increase in visceral adiposity. However, an additional contributor to increased visceral adiposity is the effect of DSAP lesions on the respiratory exchange ratio (RER). Li et al. (38) reported that DSAP-lesioned animals significantly increased RER during the day and night compared with intact animals, with no alteration of the day-night differences in energy expenditure. Therefore, the shift from fat to carbohydrate in their fuel utilization was greater in DSAP-lesioned than intact animals. Li and colleagues (38) interpret their results as revealing an important role for forebrain-projecting catecholaminergic neurons in metabolic substrate selection, a conclusion that is supported by our findings. Therefore, changes in RER and glucose homeostasis, and particularly hyperinsulinemia, are well positioned to shunt more calories toward fat deposition in DSAP-lesioned than intact animals. These effects are markedly amplified when DSAP animals are offered the HFSC diet. Under these circumstances, they consume significantly more carbohydrate calories than do DSAP-chow animals.

Dysfunction in High-Fat/High-Sucrose Choice Diet-Fed Animals

We show that removal of catecholaminergic signaling in selected forebrain targets has substantial long-term metabolic consequences with obesogenic diets. Levin and colleagues reported altered catecholaminergic signaling in the hypothalamus of diet-sensitive rats. When these rats were presented with a high-calorie diet, norepinephrine turnover in the PVH, DMH, LHA, and ventromedial hypothalamus was reduced, PVH responsiveness to norepinephrine was reduced, and hypothalamic α2-adrenoceptor function and plasticity were reduced (31, 32, 35–37). Furthermore, diet-resistant, but not diet-sensitive, animals change their food efficiency in response to a high-calorie diet (31), which again is associated with impaired catecholaminergic signaling, in this case adaptive α2-adrenoceptor function (31). Therefore, impaired catecholaminergic signaling in diet-sensitive rats provides a framework to help explain why the lack of catecholaminergic signaling in DSAP-lesioned rats alters their ability to effectively partition carbohydrate and fat from a given diet (38). Our results reveal three mechanisms for mediating the effects of disrupted catecholaminergic signaling.

Altered calorie requirement from ingested carbohydrates.

Consistent with previous reports (31, 43−45, 51), MSAP-lesioned animals adapt to the HFSC diet by increasing the number of calories required to increase their per-unit body weight, i.e., by decreasing their food efficiency. This adaptation helps restrain body weight increases when animals eat more calorically dense diets. However, DSAP-lesioned animals maintain the same food efficiency they have with chow and use fewer calories to increase their per-unit body weight than their intact counterparts. Therefore, a significant contributor to the increased sensitivity of DSAP-lesioned animals to DIO is their inability to adapt their food efficiency when presented with the HFSC diet.

The obesogenic sensitivity of DSAP-lesioned animals to the HFSC diet is clearly evident when we compare the weight of their visceral fat pads with that of MSAP-lesioned animals on the same diet. While increased calorie intake, and particularly the substantially increased carbohydrate intake, must certainly contribute to this outcome, we show that increased visceral adiposity is not explained solely by increased carbohydrate intake. DSAP-HFSC animals increase their visceral adiposity beyond that in intact controls for the same calorie intake. The increased adiposity in DSAP-HFSC animals is associated with a significantly greater contribution from carbohydrate-derived calories than in MSAP animals. As with the early-onset hyperinsulinemia in DSAP-chow animals, their underlying mechanisms must involve how the forebrain controls carbohydrate metabolism, perhaps via increased insulin secretion.

We show that MSAP-HFSC and DSAP-HFSC animals ingest appreciably less fat- than carbohydrate-derived calories. Importantly, however, the impact of these fat-derived calories on visceral fat accumulation is unaffected in DSAP-lesioned animals. Therefore, unlike carbohydrate-derived calories, catecholaminergic projections to the MBH do not impact the way fat-derived calories from the HFSC diet are distributed to visceral fat. However, it remains to be determined whether these mechanisms are carbohydrate-specific or whether they apply to all ingested calories, irrespective of their dietary source.

Disrupted glucocorticoid feedback mechanisms in the PVH.

Moderate and extended elevations of corticosterone secretion suppress food intake and PVH Crh expression and restrain body weight increases in chow-fed animals (45, 68). These changes are blocked by DSAP (25). The increased corticosterone secretion in DIO animals (59) should increase negative-feedback signals to the PVH and, thereby, limit corticosterone secretion from the adrenal gland. Consistent with this mechanism, we found that PVH CRH-ir was significantly reduced in MSAP-HFSC compared with MSAP-chow animals, despite unchanged adrenal and thymus weights in these two groups. These results indicate that glucocorticoid feedback mechanisms are functioning normally in MSAP-HFSC animals and will reduce CRH drive from the PVH, limit corticosterone secretion, and help reduce the ability of corticosterone to increase visceral adiposity with HFSC feeding.

We show that the absence of catecholamine projections compromises glucocorticoid feedback to the PVH in HFSC-fed animals. Unlike MSAP-HFSC animals, DSAP-HFSC animals did not reduce their PVH CRH, despite evidence indicating higher ACTH and glucocorticoid secretion than in MSAP-HFSC animals. We previously reported this feedback deficit for CRH mRNA regulation in DSAP-lesioned rats (23). Therefore, glucocorticoid resistance in the PVH of DSAP-HFSC animals further increases circulating corticosterone and, therefore, exacerbates sucrose intake and adiposity, most likely in conjunction with hyperinsulinemia (8, 11, 45) and the increased NPY activity in the ARH and other hypothalamic sites (52, 57). Two sets of findings support this idea: 1) mifepristone, a selective glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, restrains the increases in blood glucose, body weight, and fat mass that follow a high-fat/high-sucrose diet in mice or high-fat diets in rats (2, 4, 63); and 2) glucocorticoid action in the ARH increases NPY mRNA levels and hepatic insulin resistance in a NPY1 receptor-dependent manner (70).

Disrupted ARH neuropeptide gene expression.

As effectors of hormone and circulating nutrient signaling, ARH POMC and AgRP/NPY neurons are vital contributors to energy balance control. They help control eating behavior, insulin release, energy expenditure, and carbohydrate calorie distribution (22, 40, 56). Because they receive and respond to catecholaminergic inputs (14, 27), ARH neurons are well positioned to mediate the responses of DSAP-lesioned animals to dietary challenges. We show that this control is compromised when DSAP-lesioned animals are presented with the HFSC diet.

The effects of dietary manipulations on ARH NPY are complex and macronutrient-dependent (28, 64). High-sucrose/high-carbohydrate diets reduce PVH NPY content (5) and ARH Npy expression (39). Beck proposed that this counterregulatory mechanism limits overconsumption and fat accumulation in the presence of high-calorie diets (5). Our intact MSAP-HFSC animals also reduce ARH NPY mRNA, showing that they can use this mechanism to limit their consumption and visceral fat accumulation by reducing food efficiency. However, like their food efficiency and CRH-ir responses, DSAP-HFSC animals retain the higher ARH Npy expression of DSAP-chow animals. This increased ARH NPY is well positioned to drive the higher calorie intake and increased visceral adiposity in DSAP-HFSC animals compared with MSAP-HFSC animals. These results suggest that catecholamine projections to the ARH are part of the mechanism that limits the overconsumption of the HFSC diet and the accompanying increase in visceral adiposity.

DSAP-HFSC animals had decreased levels of AgRP mRNA and increased levels of POMC mRNA; these findings are consistent with their higher calorie intake and plasma leptin concentration. Notably, our ARH NPY and AgRP mRNA results in chow-fed animals contrast with those reported by Fraley and Ritter (14), who found that DSAP increased mRNA levels of both AgRP and POMC in the absence of overt obesity. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear but could be related to the longer survival times in our experiments. However, increased NPY and AgRP mRNA levels during the early postlesion period, as reported by Fraley and Rittter (14), would be an additional contributor to the slowly developing metabolic dysfunction we see in DSAP-chow rats.

Perspectives and Significance

We show that catecholamine neurons, primarily in the VLM and NTS, convey essential feedback signals to a highly interconnected forebrain network that enables long-term adaptive control of energy metabolism when animals consume a predominantly carbohydrate diet (Fig. 7). This is the first report specifically associating this projection system with the long-term control of adiposity, rather than its better-known role in controlling rapid responses to short-term metabolic perturbations (25, 26, 30, 46, 47, 50). We show that long-term control of insulin and glucocorticoid secretion, together with disrupted ARH neuronal function, likely mediates this adaptation. Disruption of these critical feedback systems means that catecholamine targets in this network no longer adapt energy balance mechanisms when faced with the marked increase in carbohydrate calorie intake (Fig. 7). This leads to altered carbohydrate-derived calorie distribution to visceral fat and a dramatic increase in visceral adiposity. Identifying hindbrain-to-forebrain catecholamine signaling as an important determinant in the obesogenic sensitivity to foods with high carbohydrate content may have important implications for understanding how human physiology responds to the sugar-dense foods prevalent in current diets.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation Marie Heim-Vögtlin Grant PMPDP3 151360 (to S. J. Lee), Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grant 1-710-2008 (to A. G. Watts), Swiss National Science Foundation International Short Visits Grant IZK0Z3 158027, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01 NS-029728.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.J.L. and A.G.W. conceived and designed research; S.J.L., A.J.J., G.S.-W., and A.G.W. performed experiments; S.J.L., A.J.J., G.S.-W., and A.G.W. analyzed data; S.J.L., A.J.J., G.S.-W., and A.G.W. interpreted results of experiments; S.J.L. and A.G.W. prepared figures; S.J.L. and A.G.W. drafted manuscript; S.J.L., G.S.-W., and A.G.W. edited and revised manuscript; S.J.L., A.J.J., G.S.-W., and A.G.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Prof. Wolfgang Langhans (ETH Zürich) for support during the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akana SF, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Relationships among adrenal weight, corticosterone, and stimulated adrenocorticotropin levels in rats. Endocrinology 113: 2226–2231, 1983. doi: 10.1210/endo-113-6-2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asagami T, Belanoff JK, Azuma J, Blasey CM, Clark RD, Tsao PS. Selective glucocorticoid receptor (GR-II) antagonist reduces body weight gain in mice. J Nutr Metab 2011: 235389, 2011. doi: 10.1155/2011/235389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banihashemi L, Rinaman L. Noradrenergic inputs to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus underlie hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis but not hypophagic or conditioned avoidance responses to systemic yohimbine. J Neurosci 26: 11442–11453, 2006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3561-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaudry JL, Dunford EC, Teich T, Zaharieva D, Hunt H, Belanoff JK, Riddell MC. Effects of selective and non-selective glucocorticoid receptor II antagonists on rapid-onset diabetes in young rats. PLoS One 9: e91248, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck B. Neuropeptide Y in normal eating and in genetic and dietary-induced obesity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 361: 1159–1185, 2006. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bienkowski MS, Rinaman L. Noradrenergic inputs to the paraventricular hypothalamus contribute to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and central Fos activation in rats after acute systemic endotoxin exposure. Neuroscience 156: 1093–1102, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacho J, Sevillano J, de Castro J, Herrera E, Ramos MP. Validation of simple indexes to assess insulin sensitivity during pregnancy in Wistar and Sprague-Dawley rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E1269–E1276, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90207.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell JE, Peckett AJ, D’souza AM, Hawke TJ, Riddell MC. Adipogenic and lipolytic effects of chronic glucocorticoid exposure. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C198–C209, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00045.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham ET Jr, Bohn MC, Sawchenko PE. Organization of adrenergic inputs to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 292: 651–667, 1990. doi: 10.1002/cne.902920413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham ET Jr, Sawchenko PE. Anatomical specificity of noradrenergic inputs to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the rat hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol 274: 60–76, 1988. doi: 10.1002/cne.902740107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dallman MF, Warne JP, Foster MT, Pecoraro NC. Glucocorticoids and insulin both modulate caloric intake through actions on the brain. J Physiol 583: 431–436, 2007. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.136051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinh TT, Flynn FW, Ritter S. Hypotensive hypovolemia and hypoglycemia activate different hindbrain catecholamine neurons with projections to the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R870–R879, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00094.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong HW, Petrovich GD, Watts AG, Swanson LW. Basic organization of projections from the oval and fusiform nuclei of the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis in adult rat brain. J Comp Neurol 436: 430–455, 2001. doi: 10.1002/cne.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraley GS, Ritter S. Immunolesion of norepinephrine and epinephrine afferents to medial hypothalamus alters basal and 2-deoxy-d-glucose-induced neuropeptide Y and agouti gene-related protein messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the arcuate nucleus. Endocrinology 144: 75–83, 2003. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao H, Molinas AJR, Miyata K, Qiao X, Zsombok A. Overactivity of liver-related neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: electrophysiological findings in db/db mice. J Neurosci 37: 11140–11150, 2017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geerling JC, Shin JW, Chimenti PC, Loewy AD. Paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus: axonal projections to the brainstem. J Comp Neurol 518: 1460–1499, 2010. doi: 10.1002/cne.22283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grill HJ, Hayes MR. Hindbrain neurons as an essential hub in the neuroanatomically distributed control of energy balance. Cell Metab 16: 296–309, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Depuy SD, Burke PG, Abbott SB. C1 neurons: the body’s EMTs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R187–R204, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillebrand JJ, Langhans W, Geary N. Validation of computed tomographic estimates of intra-abdominal and subcutaneous adipose tissue in rats and mice Obesity (Silver Spring) 18: 848–853, 2010. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ionescu E, Coimbra CC, Walker CD, Jeanrenaud B. Paraventricular nucleus modulation of glycemia and insulinemia in freely moving lean rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 257: R1370–R1376, 1989. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.6.R1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jokiaho AJ, Donovan CM, Watts AG. The rate of fall of blood glucose during hypoglycemia determines the necessity of forebrain-projecting catecholaminergic neurons for male rat adrenomedullary responses. Diabetes 63: 2854–2865, 2014. doi: 10.2337/db13-1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joly-Amado A, Denis RG, Castel J, Lacombe A, Cansell C, Rouch C, Kassis N, Dairou J, Cani PD, Ventura-Clapier R, Prola A, Flamment M, Foufelle F, Magnan C, Luquet S. Hypothalamic AgRP-neurons control peripheral substrate utilization and nutrient partitioning. EMBO J 31: 4276–4288, 2012. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaminski KL, Watts AG. Intact catecholamine inputs to the forebrain are required for appropriate regulation of CRH and vasopressin gene expression by corticosterone in the rat paraventricular nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol 24: 1517–1526, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012.02363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay-Nishiyama C, Watts AG. Dehydration modifies somal CRH immunoreactivity in the rat hypothalamus: an immunocytochemical study in the absence of colchicine. Brain Res 822: 251–255, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan AM, Kaminski KL, Sanchez-Watts G, Ponzio TA, Kuzmiski JB, Bains JS, Watts AG. MAP kinases couple hindbrain-derived catecholamine signals to hypothalamic adrenocortical control mechanisms during glycemia-related challenges. J Neurosci 31: 18479–18491, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4785-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan AM, Ponzio TA, Sanchez-Watts G, Stanley BG, Hatton GI, Watts AG. Catecholaminergic control of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in paraventricular neuroendocrine neurons in vivo and in vitro: a proposed role during glycemic challenges. J Neurosci 27: 7344–7360, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0873-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan AM, Walker EM, Dominguez N, Watts AG. Neural input is critical for arcuate hypothalamic neurons to mount intracellular signaling responses to glycemic challenges in male rats: implications for communication within feeding and metabolic control networks. Endocrinology 155: 405–416, 2014. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.la Fleur SE, van Rozen AJ, Luijendijk MC, Groeneweg F, Adan RA. A free-choice high-fat high-sugar diet induces changes in arcuate neuropeptide expression that support hyperphagia. Int J Obes 34: 537–546, 2010. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.la Fleur SE, Vanderschuren LJ, Luijendijk MC, Kloeze BM, Tiesjema B, Adan RA. A reciprocal interaction between food-motivated behavior and diet-induced obesity. Int J Obes 31: 1286–1294, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SJ, Diener K, Kaufman S, Krieger J-P, Pettersen KG, Jejelava N, Arnold M, Watts AG, Langhans W. Limiting glucocorticoid secretion increases the anorexigenic property of Exendin-4. Mol Metab 5: 552–565, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin BE, Hamm MW. Plasticity of brain α-adrenoceptors during the development of diet-induced obesity in the rat. Obes Res 2: 230–238, 1994. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin BE, Planas B. Defective glucoregulation of brain α2-adrenoceptors in obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 264: R305–R311, 1993. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.2.R305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin BE, Triscari J, Hogan S, Sullivan AC. Resistance to diet-induced obesity: food intake, pancreatic sympathetic tone, and insulin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 252: R471–R478, 1987. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.3.R471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levin BE, Triscari J, Sullivan AC. Metabolic features of diet-induced obesity without hyperphagia in young rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 251: R433–R440, 1986. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.3.R433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levin BE. Obesity-prone and -resistant rats differ in their brain [3H]paraminoclonidine binding. Brain Res 512: 54–59, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91169-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levin BE. Reduced norepinephrine turnover in organs and brains of obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 268: R389–R394, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.2.R389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levin BE. Reduced paraventricular nucleus norepinephrine responsiveness in obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 270: R456–R461, 1996. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.2.R456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li AJ, Wang Q, Dinh TT, Wiater MF, Eskelsen AK, Ritter S. Hindbrain catecholamine neurons control rapid switching of metabolic substrate use during glucoprivation in male rats. Endocrinology 154: 4570–4579, 2013. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindqvist A, Baelemans A, Erlanson-Albertsson C. Effects of sucrose, glucose and fructose on peripheral and central appetite signals. Regul Pept 150: 26–32, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menéndez JA, McGregor IS, Healey PA, Atrens DM, Leibowitz SF. Metabolic effects of neuropeptide Y injections into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Brain Res 516: 8–14, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90890-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehran AE, Templeman NM, Brigidi GS, Lim GE, Chu KY, Hu X, Botezelli JD, Asadi A, Hoffman BG, Kieffer TJ, Bamji SX, Clee SM, Johnson JD. Hyperinsulinemia drives diet-induced obesity independently of brain insulin production. Cell Metab 16: 723–737, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munck A, Guyre PM, Holbrook NJ. Physiological functions of glucocorticoids in stress and their relation to pharmacological actions. Endocr Rev 5: 25–44, 1984. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-1-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oosterman JE, Foppen E, van der Spek R, Fliers E, Kalsbeek A, la Fleur SE. Timing of fat and liquid sugar intake alters substrate oxidation and food efficiency in male Wistar rats. Chronobiol Int 32: 289–298, 2015. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2014.971177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panchal SK, Poudyal H, Iyer A, Nazer R, Alam MA, Diwan V, Kauter K, Sernia C, Campbell F, Ward L, Gobe G, Fenning A, Brown L. High-carbohydrate, high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular remodeling in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 57: 611–624, 2011. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181feb90a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pecoraro N, Gomez F, Dallman MF. Glucocorticoids dose-dependently remodel energy stores and amplify incentive relativity effects. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30: 815–825, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rinaman L. Hindbrain noradrenergic lesions attenuate anorexia and alter central cFos expression in rats after gastric viscerosensory stimulation. J Neurosci 23: 10084–10092, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritter S, Bugarith K, Dinh TT. Immunotoxic destruction of distinct catecholamine subgroups produces selective impairment of glucoregulatory responses and neuronal activation. J Comp Neurol 432: 197–216, 2001. doi: 10.1002/cne.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ritter S, Dinh TT, Bugarith K, Salter DM. Chemical dissection of brain glucoregulatory circuitry. In: Molecular Neurosurgery with Targeted Toxins, edited by Wiley RG, Lappi DA. Totowa, NJ: Humana, 2005. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59259-896-0_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ritter S, Li AJ, Wang Q, Dinh TT. The value of looking backward: the essential role of the hindbrain in counterregulatory responses to glucose deficit. Endocrinology 152: 4019–4032, 2011. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ritter S, Watts AG, Dinh TT, Sanchez-Watts G, Pedrow C. Immunotoxin lesion of hypothalamically projecting norepinephrine and epinephrine neurons differentially affects circadian and stressor-stimulated corticosterone secretion. Endocrinology 144: 1357–1367, 2003. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roberts CK, Berger JJ, Barnard RJ. Long-term effects of diet on leptin, energy intake, and activity in a model of diet-induced obesity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 93: 887–893, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00224.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sainsbury A, Cusin I, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Jeanrenaud B. Adrenalectomy prevents the obesity syndrome produced by chronic central neuropeptide Y infusion in normal rats. Diabetes 46: 209–214, 1997. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Central noradrenergic pathways for the integration of hypothalamic neuroendocrine and autonomic responses. Science 214: 685–687, 1981. doi: 10.1126/science.7292008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schiltz JC, Sawchenko PE. Specificity and generality of the involvement of catecholaminergic afferents in hypothalamic responses to immune insults. J Comp Neurol 502: 455–467, 2007. doi: 10.1002/cne.21329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shanik MH, Xu Y, Skrha J, Dankner R, Zick Y, Roth J. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: is hyperinsulinemia the cart or the horse? Diabetes Care 31 Suppl 2: S262–S268, 2008. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shin AC, Filatova N, Lindtner C, Chi T, Degann S, Oberlin D, Buettner C. Insulin receptor signaling in POMC, but not AgRP, neurons controls adipose tissue insulin action. Diabetes 66: 1560–1571, 2017. doi: 10.2337/db16-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strack AM, Sebastian RJ, Schwartz MW, Dallman MF. Glucocorticoids and insulin: reciprocal signals for energy balance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 268: R142–R149, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.1.R142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swanson LW. Brain Maps: Structure of the Rat Brain (3rd ed). The Netherlands: Academic; (Open access available at http://larrywswanson.com/?page_id=164). 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tannenbaum BM, Brindley DN, Tannenbaum GS, Dallman MF, McArthur MD, Meaney MJ. High-fat feeding alters both basal and stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in the rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 273: E1168–E1177, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Templeman NM, Skovsø S, Page MM, Lim GE, Johnson JD. A causal role for hyperinsulinemia in obesity. J Endocrinol 232: R173–R183, 2017. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson RH, Swanson LW. Structural characterization of a hypothalamic visceromotor pattern generator network. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 41: 153–202, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(02)00232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tritos NA, Elmquist JK, Mastaitis JW, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E. Characterization of expression of hypothalamic appetite-regulating peptides in obese hyperleptinemic brown adipose tissue-deficient (uncoupling protein-promoter-driven diphtheria toxin A) mice. Endocrinology 139: 4634–4641, 1998. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.11.6308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van den Heuvel JK, Boon MR, van Hengel I, Peschier-van der Put E, van Beek L, van Harmelen V, van Dijk KW, Pereira AM, Hunt H, Belanoff JK, Rensen PC, Meijer OC. Identification of a selective glucocorticoid receptor modulator that prevents both diet-induced obesity and inflammation. Br J Pharmacol 173: 1793–1804, 2016. doi: 10.1111/bph.13477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van den Heuvel JK, Eggels L, Fliers E, Kalsbeek A, Adan RAH, la Fleur SE. Differential modulation of arcuate nucleus and mesolimbic gene expression levels by central leptin in rats on short-term high-fat high-sugar diet. PLoS ONE: 9: e87729, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watts AG, Sanchez-Watts G, Kelly AB. Distinct patterns of neuropeptide gene expression in the lateral hypothalamic area and arcuate nucleus are associated with dehydration-induced anorexia. J Neurosci 19: 6111–6121, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watts AG, Sanchez-Watts G. Physiological regulation of peptide messenger RNA colocalization in rat hypothalamic paraventricular medial parvicellular neurons. J Comp Neurol 352: 501–514, 1995. doi: 10.1002/cne.903520403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Watts AG, Tanimura S, Sanchez-Watts G. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin gene transcription in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of unstressed rats: daily rhythms and their interactions with corticosterone. Endocrinology 145: 529–540, 2004. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Watts AG. Glucocorticoid regulation of peptide genes in neuroendocrine CRH neurons: a complexity beyond negative feedback. Front Neuroendocrinol 26: 109–130, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Woulfe JM, Hrycyshyn AW, Flumerfelt BA. Collateral axonal projections from the A1 noradrenergic cell group to the paraventricular nucleus and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the rat. Exp Neurol 102: 121–124, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(88)90084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yi CX, Foppen E, Abplanalp W, Gao Y, Alkemade A, la Fleur SE, Serlie MJ, Fliers E, Buijs RM, Tschöp MH, Kalsbeek A. Glucocorticoid signaling in the arcuate nucleus modulates hepatic insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 61: 339–345, 2012. doi: 10.2337/db11-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]