Procedural training for fellows is an ongoing debate within the nephrology community. This Perspectives article outlines the evolution of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements for procedural training in nephrology and the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Nephrology Initial Certification Examination eligibility requirements. Also, procedural competence reporting and data about graduating nephrology fellows’ performance on the ACGME invasive procedure subcompetency are discussed. Finally, alternate approaches to conceptualizing procedural training in other specialties are described.

Which Procedures Must Nephrology Fellows Learn?

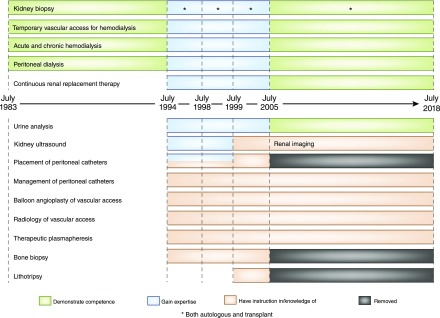

The Internal Medicine Subspecialty Milestones Project was a collaboration among the ACGME, ABIM, and subspecialty societies, including the American Society of Nephrology (ASN), to develop uniform reporting milestones for 23 subcompetencies in which all subspecialty fellows are evaluated twice yearly by clinical competence committees in their training programs. The “patient care” competency further subdivides procedural skills into invasive (PC-4a) and noninvasive (PC-4b) subcompetencies (1). Because the reporting milestones are intentionally generic, each subspecialty subsequently developed its own curricular milestones, completed by ASN in 2014. These remain in implementation draft form (2). Invasive procedures are kidney biopsy (both autologous and transplant) and placement of temporary vascular access. Noninvasive procedures are hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, continuous renal replacement therapy, and urine analysis. Over time, nephrology fellowship training requirements have changed to reflect advances in technology and practice (Figure 1) (3). Although contemporary nephrology practice has transformed considerably, the ACGME program requirements in effect since 2012 include procedural requirements unchanged since 2005 (3,4).

Figure 1.

ACGME procedural requirements for nephrology fellowship training have evolved over time (3,4).

Eligibility to take the ABIM Initial Certification Examination in nephrology requires fellows to complete 24 months in an ACGME-accredited fellowship program. In addition, training program directors must certify that graduating fellows can satisfactorily perform the aforementioned procedures, with the exception of urine analysis (5). Therefore, ABIM initial certification implies that nephrologists can competently perform these procedures.

How Is Procedural Competence Ascertained?

This multifaceted question is difficult to answer definitively. The nephrology curricular milestones rubric lists milestone elements for each of the five levels (with level one indicating critical deficiency, level two indicating appropriate for a beginning fellow, level three indicating appropriate for a midlevel fellow, level four indicating ready for unsupervised practice, and level five indicating aspirational) (1). Designating a level is not straightforward, and fellows are not required to demonstrate competency in every milestone element for each level (6). Although competency-based assessment tools such as checklists may be utilized, there are few standardized, validated tools available (4). Furthermore, overall competence includes not only technical skills, but also counseling regarding procedural indications and potential risks as well as interpretation of results, in the case of kidney biopsy. Ultimately, individual programs define the criteria for procedural competence that inform the designation of “ready for unsupervised practice.”

Moreover, the internal medicine subspecialty reporting milestones have yet to be validated. Ongoing studies seek to establish whether milestone elements are appropriately assigned, individually and in aggregate, to the levels within each subcompetency. Therefore, “ready for unsupervised practice” is not a requirement but rather a graduation target (1). In fact, a fellow may have “the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to demonstrate the appropriate competency to ensure the delivery of safe, effective, efficient, timely, equitable patient centered care” without achieving the level of ready for unsupervised practice in every subcompetency (6). ACGME data from 2015 show that only 77% of 7157 internal medicine residents attained all graduation targets within the patient care competency (7). Rather than concluding that a substantial proportion of graduating residents are not competent to provide patient care, it is essential to recognize that our systems for determining competence are imperfect, not only because of limitations of the assessment tools, but also because the current milestones framework itself may not be sufficiently accurate.

Can Graduating Nephrology Fellows Competently Perform Procedures?

The ACGME 2017 Milestones Annual Report details trainees’ competency level ratings for each subcompetency in all ACGME-accredited programs. Among 405 graduating nephrology fellows, the median rating on the invasive procedure subcompetency was at level four, with an interquartile range of 4–4.5 and overall range of 3.5–5, excluding outliers (8). In other words, 75% of fellows were rated as ready for unsupervised practice or better. However, approximately 100 fellows (25%) were rated between appropriate for midlevel fellow and ready for unsupervised practice (2,7). Importantly, the invasive procedure subcompetency reporting does not distinguish between temporary dialysis catheter placement and kidney biopsy. Hence, it is impossible to establish whether a rating below level four indicates suboptimal performance of one or both invasive procedures.

Is Procedural Competence for Fellows All or Nothing?

A crucial question is whether every nephrology fellow must achieve competence in either or both temporary dialysis catheter placement and kidney biopsy. Through extensive discussions in recent years, including during multiple ASN Training Program Director annual retreats, it seems clear that some fellows are not interested in performing invasive procedures and/or do not anticipate performing these procedures during their careers. Others, however, are attracted to nephrology at least partly because of the opportunity to perform procedures. Moreover, depending on their practice settings, some nephrologists perform invasive procedures often enough to maintain competence, whereas others perform these rarely or not at all. A one-size-fits-all solution seems unlikely to succeed.

Other internal medicine subspecialties approach procedural competence differently. For instance, the ABIM Certification policy in hematology includes the statement, “Training programs are strongly encouraged to make additional training and experiences available for their trainees who anticipate the need to perform specified procedures in their post‐training careers.” (5). On the other hand, cardiology developed the Core Cardiovascular Training Statement, recently published in its fourth iteration, which defines training in terms of three levels (9). Level I comprises “the basic training required of all trainees to be competent cardiologists,” expected during a standard 3-year fellowship. Level II denotes optional additional training in performance or interpretation of specific tests and procedures or providing care to certain types of patients with defined conditions. On the basis of individual career goals, in addition to completing all level I core requirements, some fellows may elect to pursue level II training in various area(s) during a standard fellowship. Notably, a nationally accepted benchmark must exist (9). In nephrology, for example, the American Society for Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology has defined explicit criteria for obtaining certification in ultrasound, peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion, and hemodialysis vascular access (10). The Core Cardiovascular Training Statement level III training denotes additional specialized training beyond the scope of a general cardiology fellowship, analogous to the 1-year Kidney Transplant Fellowship accredited by the American Society of Transplantation. Future conversations related to procedural competence in nephrology could explore whether these or other similar solutions might fit our circumstances.

In summary, no universal standard for measuring competence to perform the invasive procedures required for nephrology fellowship training exists. Although competency-based rubrics designed to document progression of nephrology fellows’ skill acquisition are not yet validated, ACGME data suggests that 25% of fellows completing training in 2017 were not considered ready to perform temporary dialysis catheter placement and/or kidney biopsy without supervision. As we continue the conversation about procedural requirements in nephrology, a formidable opportunity exists to shape the future of our specialty, and it is our responsibility to consider a variety of possibilities to ultimately reach an optimal decision.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Henry Schultz for his inimitable mentorship in graduate medical education, as well as past and present Mayo Clinic nephrology fellows for their continuous inspiration.

The content of this article does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (CJASN). Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related articles, “Training Nephrology Fellows in Temporary Hemodialysis Catheter Placement and Kidney Biopsies is Needed and Should be Required,” “Training Nephrology Fellows in Temporary Hemodialysis Catheters and Kidney Biopsies Is Not Needed and Should Not Be Required,” and “Kidney Biopsy Training and the Future of Nephrology: What about the Patient?,” on pages 1099–1101, 1102–1104, and 1105–1106, respectively.

References

- 1.The Internal Medicine Subspecialty Milestones Project: A Joint Initiative of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Internal Medicine, 2015. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineSubspecialtyMilestones.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2018

- 2.American Society of Nephrology Training Program Directors: Nephrology Curricular Milestones: Implementation Draft, 2014. Available at: https://www.asn-online.org/education/training/tpd/ASN_Nephrology_Curricular_Milestones.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018

- 3.American Medical Association: Graduate Medical Education Handbooks (Archived), 1983–2006. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publications-and-Resources/AMA-Green-Books. Accessed February 13, 2018

- 4.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Nephrology (Internal Medicine), 2017. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/148_nephrology_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018

- 5.American Board of Internal Medicine: Policies and Procedures for Certification, 2018. Available at: http://www.abim.org/∼/media/ABIM%20Public/Files/pdf/publications/certification-guides/policies-and-procedures.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2018

- 6.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: Internal Medicine Subspecialty Reporting Milestones Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs), 2015. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineSubspecialtyMilestonesFAQs.pdf?ver=2015-11-06-120527-423. Accessed February 14, 2018.

- 7.Edgar L, Hamstra S: ACGME Milestones Project: Lessons Learned and What's Next, 2015. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Webinars/Milestones%20Lessons%20Learned%20Webinar%20_%20August%2018.pdf?ver=2015-11-06-120542-227. Accessed February 14, 2018

- 8.Hamstra S, Edgar L, Yamazaki K, Holmboe E: Milestones Annual Report, October 2017. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/MilestonesAnnualReport2017.pdf?ver=2018-02-09-074057-013. Accessed February 15, 2018

- 9.Halperin JL, Williams ES, Fuster V: COCATS 4 introduction. J Am Coll Cardiol 65: 1724–1733, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology: Certification, 2017. Available at: http://www.asdin.org/?page=2. Accessed February 18, 2018