To the Editor: Gorham–Stout syndrome (GSS) is a rare disorder of uncertain etiology. GSS presents with lytic destruction of one or more bones, which may also include chylous effusion in the pleurae, peritoneum, and cystic lesions in visceral organs, such as the spleen. Herein, we report a brief case for Gorham–Stout syndrome of the femur with chylothorax and chyloperitoneum in a patient. No report of GSS presenting in this manner has been documented to date. Our present case emphasizes the clinical, radiological, and histological features and proper treatment of Gorham–Stout syndrome.

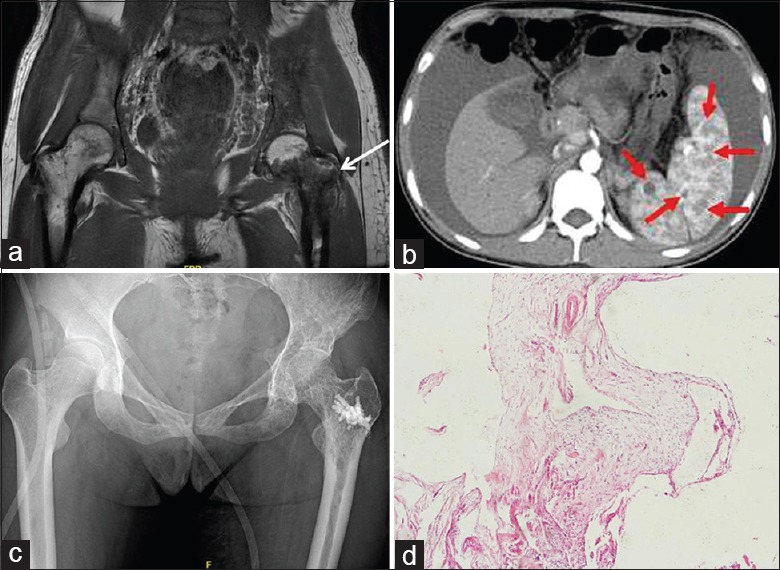

In 2012, a 27-year-old woman was admitted to another hospital with abdominal distention and hip pain of the left side. Computed tomography and ultrasonography revealed massive hydrothorax and ascites. Cavity puncture was performed, and chylothorax and chyloperitoneum were confirmed, as well as bony destruction of her left femur. She presented to our institution with worsened abdominal distention and bony destruction. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed massive bony destruction of the left femur [Figure 1a, arrow]. Computed tomography and ultrasonography demonstrated massive ascites and mild hydrothorax as well as cystic lesions in the spleen [Figure 1b, arrows]. Chest and abdominal cavity puncture were performed and the result confirmed chylothorax and chyloperitoneum, and the amount of pleural and peritoneal fluid was gradually reduced. We administered combination medical treatment consisting of interferon-α-2b and zoledronic acid, and percutaneous osteoplasty of upper femur with cement augmentation was performed [Figure 1c]. The postoperative pathology was reported to be consistent with Gorham–Stout syndrome [Figure 1d]. At a 2-year follow-up visit, the patient was doing well, with improved motion, and palliative hip pain and no evidence of local progression or distant lesions.

Figure 1.

Gorham–Stout syndrome of the left femur treated with cement augmentation in a 27-year-old female. (a) Preoperative coronal T1-weighted fat-saturated magnetic resonance imaging scan revealed the bony destruction indicated by arrows. (b) Transverse plane of the computed tomography scan revealed cystic lesions in the spleen. (c) Postoperative posteroanterior radiograph of the hip showed cement augmentation was satisfactory. (d) Histopathology revealed dilated lymphatic channels in hyperplastic fibrous connective tissue with lymphocytic infiltrate among the trabeculae (H and E staining, original magnification ×40).

Gorham–Stout syndrome is an extremely rare disorder characterized by clinical and radiological disappearance of bone by proliferation of non-neoplastic lymphatic, vascular, and fibrous tissue.[1] Few GSS cases with both chylothorax and chyloperitoneum have been documented in literature; thus, there is still short of imaging proof.[2] Even though the majority of the cases show spontaneous arrest, life-threatening complications may occur due to the involvement of the bone, viscera, chylothorax, or chyloperitoneum. Bony disease remains silent until deformity, instability, or neurological deficits develop. Hence, we recommend screening of bone in the case of GSS to discount secondary involvement.[3] Asymptomatic bony disease can be managed with radiation and bisphosphonates, while those with deformity, instability, or neurological deficits require early surgical intervention, such as osteoplasty or posterior instrumentation.[2,4] The present case highlights the importance of proper surgical treatment for patients with Gorham–Stout syndrome.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that her name and initial will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal her identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Yi Cui

REFERENCES

- 1.Nikolaou VS, Chytas D, Korres D, Efstathopoulos N. Vanishing bone disease (Gorham-Stout syndrome): A review of a rare entity. World J Orthop. 2014;5:694–8. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i5.694. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i5.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sekharappa V, Arockiaraj J, Amritanand R, Krishnan V, David KS, David SG, et al. Gorham's disease of spine. Asian Spine J. 2013;7:242–7. doi: 10.4184/asj.2013.7.3.242. doi: 10.4184/asj.2013.7.3.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellinger MT, Garg N, Olsen BR. Viewpoints on vessels and vanishing bones in Gorham-Stout disease. Bone. 2014;63:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.02.011. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carbó E, Riquelme Ó, García A, González JL. Vertebroplasty in a 10-year-old boy with Gorham-Stout syndrome. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(Suppl 4):S590–3. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-3764-x. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-3764-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]