Case Report

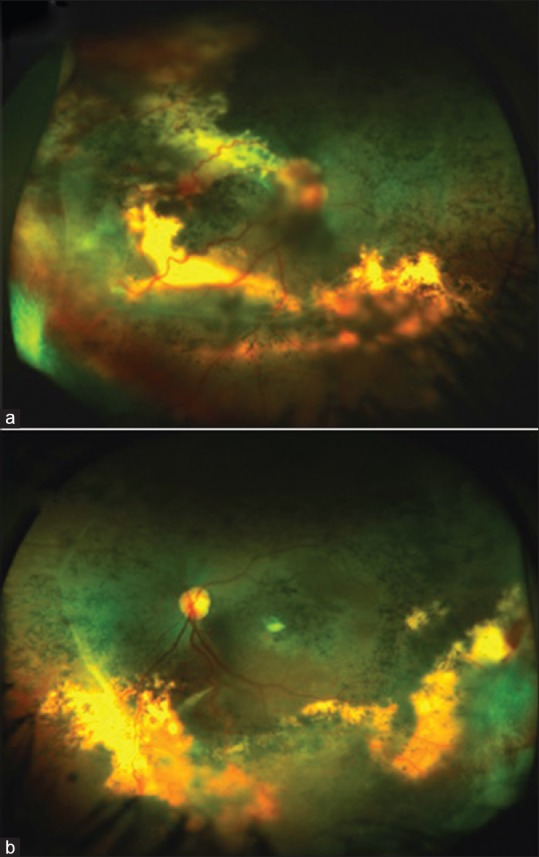

A 35-year-old female presented with gradually progressive visual loss in both eyes (OU) which started as night blindness a decade ago. Best-corrected visual acuity in OU was light perception only. Anterior segment in OU was unremarkable. Fundus revealed arteriolar attenuation and diffuse bone-spicule pigmentation involving the macula [Fig. 1a and b]. Vascular telangiectasia and lipid exudation were present in temporal and inferior retina in OU. In right eye (OD), optic disc was not evident distinctly due to prepapillary hemorhages, and exudates were present more widely and involved macula. Ultra-widefield (UWF) fluorescein angiography [Fig. 2a and b] showed patchy hypo- and hyperfluorescence corresponding to bone-spicule pigmentation, retinal sparing along the vascular arcades (especially left eye [OS]), and multiple bulb-like dilatations of vessels in inferotemporal quadrants [Fig. 2a and c]. Inferiorly steered picture in OD ([Fig. 2b] and temporally steered picture in OS [Fig. 2d] showed leakage from neovascularization in late phases. Full-field electroretinogram demonstrated extinguished responses in OU. A diagnosis with Coats’-like retinitis pigmentosa (RP) was made. The patient was explained about the prognosis.

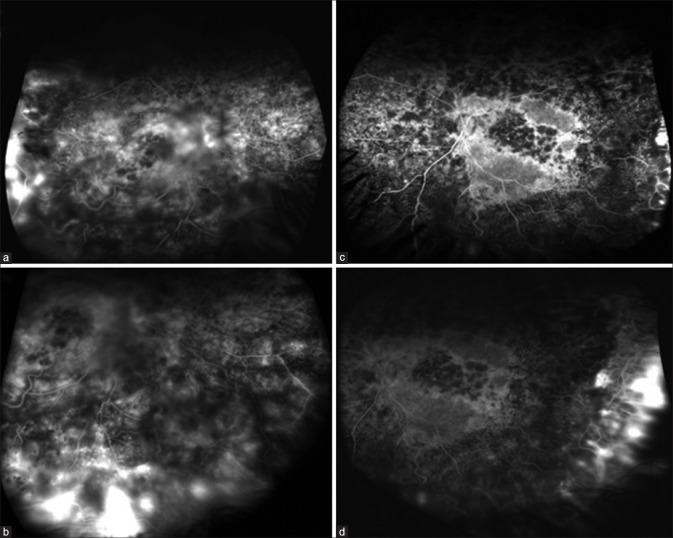

Figure 1.

Ultra-widefield pseudocolor photographs of the right (a) and left (b) eyes of a 35-year-old female showing arteriolar attenuation and diffuse bone-spicule pigmentation. Telangiectatic vessels along with intra- and subretinal exudation is present in temporal and inferior retina

Figure 2.

Ultra-widefield fluorescein angiogram of the right (a) and left (c) eyes showing retinal telangiectasia. Inferior periphery of the right eye (b) and temporal periphery of the left eye (d) showing leakage from retinal neovascularization in late phase

Discussion

Coats’-like response is seen with long-standing RP with a reported incidence of 1.2%–3.6%.[1,2] It consists of telangiectatic retinal vessels with intraretinal and subretinal exudation. In severe cases, retinal and/or choroidal neovascularization can be seen as was seen in this patient. It should not be confused with classic Coats’ disease which is an idiopathic unilateral disorder, occurs predominantly in males, and presents in the first or second decade.[3] In contrast, Coats’-type RP tends to be bilateral with slight female preponderance and presents at a later age. While Coats’ disease has a predilection for superotemporal retina, Coats’ type RP predominantly involves inferotemporal quadrant.[4]

Conclusion

UWF imaging is an excellent tool for capturing a large area of the retina in a single click. This is especially important in patients with poor vision and fixation. UWF imaging may reveal peripheral findings in addition (retinal neovascularization in this case) which may help in better documentation and characterization of the disease process.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kajiwara Y. Ocular complications of retinitis pigmentosa. Association with Coats’ syndrome. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol. 1980;34:947–55. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pruett RC. Retinitis pigmentosa: Clinical observations and correlations. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1983;81:693–735. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sigler EJ, Randolph JC, Calzada JI, Wilson MW, Haik BG. Current management of Coats disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59:30–46. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan JA, Ide CH, Strickland MP. Coats’-type retinitis pigmentosa. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32:317–32. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]