Abstract

Aims

To describe processes and outcomes of a priority setting partnership to identify the ‘top 10 research priorities’ in Type 2 diabetes, involving people living with the condition, their carers, and healthcare professionals.

Methods

We followed the four‐step James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership process which involved: gathering uncertainties using a questionnaire survey distributed to 70 000 people living with Type 2 diabetes and their carers, and healthcare professionals; organizing the uncertainties; interim priority setting by resampling of participants with a second survey; and final priority setting in an independent group of participants, using the nominal group technique. At each step the steering group closely monitored and guided the process.

Results

In the first survey, 8227 uncertainties were proposed by 2587 participants, of whom 18% were from black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. Uncertainties were formatted and collated into 114 indicative questions. A total of 1506 people contributed to a second survey, generating a shortlist of 24 questions equally weighted to the contributions of people living with diabetes and their carers and those of healthcare professionals. In the final step the ‘top 10 research priorities’ were selected, including questions on cure and reversal, risk identification and prevention, and self‐management approaches in Type 2 diabetes.

Conclusion

Systematic and transparent methodology was used to identify research priorities in a large and genuine partnership of people with lived and professional experience of Type 2 diabetes. The top 10 questions represent consensus areas of research priority to guide future research, deliver responsive and strategic allocation of research resources, and improve the future health and well‐being of people living with, and at risk of, Type 2 diabetes.

What's new?

We describe the largest research prioritization process for Type 2 diabetes to date and the first to consult extensively with healthcare professionals, people living with the condition and their carers in partnership.

The process provides an authoritative resource to the academic community to guide research that has the potential to make a meaningful difference to people living with Type 2 diabetes and healthcare professionals.

What's new?

We describe the largest research prioritization process for Type 2 diabetes to date and the first to consult extensively with healthcare professionals, people living with the condition and their carers in partnership.

The process provides an authoritative resource to the academic community to guide research that has the potential to make a meaningful difference to people living with Type 2 diabetes and healthcare professionals.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is a chronic, complex condition increasingly affecting the global population, with high morbidity and mortality from microvascular and macrovascular complications 1, and high economic burden on health systems 2. In the UK, 3.8 million people (8.6% of the population) are thought to be living with Type 2 diabetes, and the condition is twice as common in people from black, Asian and minority ethnic groups 3. A further 10.7% of the UK population are thought to be in a pre‐diabetic state 4. The UK's National Health Service (NHS) is estimated to spend £8.8 bn on treating Type 2 diabetes per year, and this is expected to nearly double in the next 20 years 5. The care and prevention of Type 2 diabetes involves multiple agencies, sectors and professional groups, aiming to deliver high‐quality care 6; however, there is an unmet and urgent need to fill knowledge gaps with research to better understand its cause and complications, deliver prevention, improve care and treatment, and reduce impact on people living with the condition, their families and health services. Currently, UK research spend on diabetes is only £60 m per year, in contrast to £165 m for cardiovascular disease and £500 m for cancer 7.

Historically, health research has been thought of as biased towards certain domains, for example, pharmaceutical treatments 8, and research funding has been poorly representative of the disease burden and lived experience 9. Others have described a mismatch between patient, clinician and research community priorities for research, highlighting that, whilst research funding prioritizes drug trials, patients prioritize research into non‐drug treatments 10. The James Lind Alliance was established to bring patients, carers and clinicians together on an equal basis in a ‘priority setting partnership’ to define the uncertainties relating to a specific condition, and prioritize them to guide future funding and investment from a wide range of research funders. The priority setting partnership process offers a systematic and transparent approach to design, process and outcomes. It forms part of a widening approach to patient and public involvement in research, and is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the INVOLVE national advisory group 11.

To date, research prioritization exercises for Type 2 diabetes in the UK appear to be few and limited in scope and scale, none appear to have taken place recently, and none have extensively consulted people living with the condition and health professionals 12, 13. As the leading charity for people affected by diabetes, Diabetes UK has multiple roles as a major UK research funder, supporting policy‐makers, and acting as advocate for high‐quality diabetes care and prevention. As such, Diabetes UK is ideally placed to undertake a priority setting partnership to reach its 110 000 diverse members and multi‐professional networks, including people living with Type 2 diabetes and carers, and healthcare professionals. Diabetes UK has previously supported a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership for Type 1 diabetes, led by the Insulin‐Dependent Diabetes Trust and, whilst successful in generating a set of research priorities for the condition 14, has been criticized for being an unequal partnership between people living with diabetes and their carers and healthcare professionals, leading to missed opportunities 15. This, and some other priority setting partnerships have been limited by modest participant numbers and low representation of black and minority ethnic groups.

The Diabetes UK–James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership in Type 2 diabetes was established in 2015 with a commitment to address the limitations identified in previous partnerships. In the present paper, we describe the methodology used to identify and order research priorities (also known as ‘uncertainties’ and ‘unanswered questions’) in Type 2 diabetes. We also explore the feasibility of the priority setting partnership process to reach and represent equitably a wide range of patient and professional views, whilst limiting potential biases. Finally, we present future plans to disseminate the outcome of this priority setting partnership and shape the research agenda for Type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Setting up the partnership

The steering group comprised five people living with Type 2 diabetes (managing their condition in different ways), five healthcare professionals (including a dietician, diabetes specialist nurse, general practitioner and two consultant diabetologists), an information specialist, seven members of the Diabetes UK research and senior leadership team, and a James Lind Alliance senior advisor. The steering group (47% men and 53% women and 26% from black and minority ethnic groups) met 12 times during the priority setting partnership process, in person or by teleconference.

Priority setting partnership process

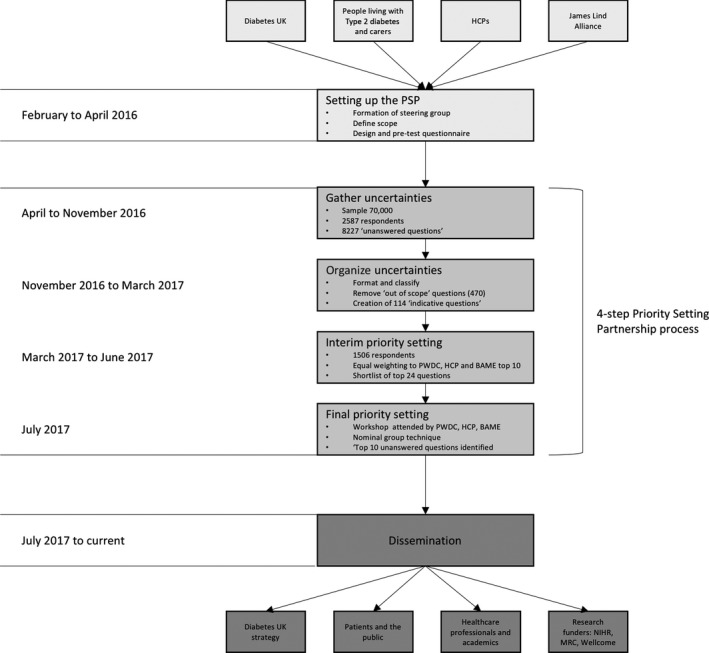

The four‐step James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership process was followed 16. This involved: (1) gathering uncertainties; (2) organizing the uncertainties; (3) interim priority setting; and (4) final priority setting (Fig. 1). The key principles of the James Lind Alliance process were followed, including transparency of process, a clear audit trial of data collected, and balanced inclusion of patients, carers and healthcare professionals. Brief descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics and results, using percentages and summary statistics.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the priority setting partnership (PSP) process, number of participants and timeline. BAME, black and minority ethnic groups; HCP, healthcare professional; NIHR, National Institute of Health Research; MRC, Medical Research Council; PWDC, people living with diabetes and their carers.

Gathering uncertainties

A questionnaire (File S1) was designed and underwent pre‐testing and optimization with a group of Diabetes UK volunteers for acceptability and ease of use. The questionnaire invited up to four answers to the question, ‘What are the questions about Type 2 diabetes you would most like to see answered by research?’, and also collected basic sociodemographic information (gender, age bracket, ethnic group, relationship to diabetes, and first three characters of the participant's postcode). Respondent postcodes were mapped using an online visualization tool (http://www.mapsdata.co.uk). The questionnaire was produced and distributed in both paper and online versions.

Distribution of the questionnaire was managed by Diabetes UK under the guidance of the steering group, and was disseminated through their existing networks, community champions, wider professional networks, opinion leaders (e.g. the NHS England National Clinical Director for Obesity and Diabetes), social media, publications, at conferences, and specific target groups. A summary of all groups approached is reported in File S2. The steering group regularly reviewed respondent numbers and inclusion of individuals from specific target groups (e.g. black, Asian and minority ethnic groups, and all multidisciplinary professional groups) and their active involvement directed purposive sampling to ensure underrepresented target groups were reached.

In addition, uncertainties were identified from existing research (File S3) and from research recommendations in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Protocols and research reports published by Diabetes UK and the South Asian Health Foundation. These were included in the prioritization setting.

Organizing uncertainties

Answers to the question, ‘What are the questions about Type 2 diabetes you would most like to see answered by research?’ were formatted to population, intervention, comparison and outcome standards and, where appropriate, were classified using a Health Research Classification System 17. Similar questions and uncertainties were then collated and grouped into lists by the steering group to form indicative summary questions ready for the next stage of the process. Submitted questions considered to be ‘out‐of‐scope’ were removed at this stage.

Interim priority setting

A second survey was carried out using the indicative summary questions. Respondents from the original survey who provided contact details were invited by email to complete an online second survey using an embedded survey link. The second survey was distributed through the same networks that were used for the first survey (File S2). Participants were asked to select the ‘10 questions that matter to them the most’ from the list of indicative questions, using a three‐stage process which involved: (1) selecting the questions where they thought more research was needed; (2) selecting the top 10 that were most important and (3) putting the top 10 in rank order.

The final top 10 research priorities chosen and ranked by participants were checked and collated for each target group: people living with diabetes and carers, and healthcare professionals. In addition, the priorities of black, Asian and minority ethnic groups were identified and reviewed by the steering group to ensure adequate representation. Research priorities identified by each participant were scored as follows: a research priority ranked 1 was given 10 points, rank 2 was given 9 points, and so on down to rank 10 which was given 1 point. Total points per research priority were calculated based on all responses and then research priorities were re‐ordered from highest to lowest (using joint ranking where points were equal). This scoring process was undertaken for each of the three groups, (1) people living with diabetes and carers; (2) healthcare professionals; and (3) black, Asian and minority ethnic groups, for the steering group to produce a final shortlist of 25 questions following guidance from the James Lind Alliance.

Final priority setting

People living with diabetes, carers and multidisciplinary healthcare professionals who had not previously been involved in the process were identified through an open call and invited to attend a final workshop. The steering group reviewed the attendee invitation list to ensure adequate and equitable representation from all stakeholder groups. Observers at the workshop included representatives from Diabetes UK, the steering group and the NIHR. The workshop was facilitated by trained James Lind Alliance advisors, using the nominal group technique 18 to build consensus on the final top 10 priorities through group discussion and ranking. The steering group gave final consideration to the wording of each of the priorities before finalizing them.

Dissemination

A dissemination strategy was planned during the course of the priority setting partnership, and in advance of the final priority setting workshop. This included a lay report, publication of a brief letter summarizing the findings of the priority setting partnership, preparation of a detailed manuscript describing the methodology and recommendations of the priority setting partnership, social media campaigns and press releases on publication of findings, and planned activities at the 2018 Diabetes UK Professional Conference. Diabetes UK will also be responsible for leading the implementation of this research prioritization by, for example, focused funding calls, supported by their newly formed Clinical Studies Groups 19. The results of the priority setting partnership will also be disseminated by Diabetes UK to other major funding agencies (e.g. the NIHR, Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust) and diabetes charities (Diabetes Research and Wellness Foundation). The impact of the priority setting partnership on future research investment will be monitored and reported on by Diabetes UK. The priority setting partnership outcomes will influence the work of the Clinical Studies Groups.

Ethics statement

The James Lind Alliance methodology has public and patient involvement in research. The people who take part in the survey and priority setting stages of the work are not research participants. The UK Health Research Authority decision aid identified no need for research ethics approval.

Results

The timeline, process and outcomes of the priority setting partnership are summarized in Fig. 1 and the results are discussed below for each of the four steps of the James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership methodology.

Gathering uncertainties

The questionnaire is estimated to have reached 50 000 people living with Type 2 diabetes and their carers, and an additional 20 000 healthcare professionals. There were 2587 respondents to the questionnaire, from whom 7978 ‘research priorities’ were proposed. A total of 470 ‘out‐of‐scope’ questions were removed. These included comments on personal healthcare issues, statements which were not questions, and questions which have already been fully answered through research. Respondent characteristics are summarized in File S4, including people living with diabetes (n=1857), their carers (n=79), and healthcare professionals (n=611). Respondents were from across the UK (File S5a). Eighteen per cent of all respondents were from black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. The steering group recommended that responses from persons living with diabetes and carers were considered together because of the small number of carer respondents. Healthcare professional respondents were representative of the multidisciplinary nature of diabetes care and included nurses (diabetes specialist, practice, district, research and psychiatric nurses), doctors (diabetologists, general practitioners, renal physicians, obstetricians, public health physicians, ophthalmologists), and allied healthcare professionals (health visitors, dieticians, podiatrists, midwives, optometrists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychologists and healthcare assistants). The steering group reviewed the response throughout the uncertainty gathering process and, where necessary, made recommendations to further publicize the survey to low response groups or encourage activity in specific Diabetes UK network regions.

An additional 249 research recommendations were added to the ‘research priorities’, from the following sources: National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidance (n=94), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (n=31), Cochrane Protocols (n=37), ongoing trials (n=13), Diabetes UK and South Asian Health Foundation reports on research priorities (n=74).

Organizing uncertainties/data processing

The 8227 respondent questions and additional research recommendations were formatted, and 470 out‐of‐scope questions were removed. After formatting and classification using the UK Clinical Research Collaboration health research classification system research activity code (Table 1), the remaining 7757 questions were collated by the steering group into 114 ‘indicative questions’.

Table 1.

Respondent questions and indicative questions classified using the UK Clinical Research Collaboration health research classification system

| UKCRC health research classification system research activity code | Number of respondent questions (% of total) | Number of indicative questions (% of total) |

|---|---|---|

| Aetiology | 1157 (15) | 11 (9) |

| Prevention and promotion of well‐being | 623 (8) | 11 (9) |

| Detection, screening and diagnosis | 278 (4) | 4 (3) |

| Development of treatments | 110 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Evaluation of treatments | 2162 (28) | 14 (12) |

| Management of disease | 2160 (28) | 79 (66) |

| Health services | 1101 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Unclassified | 166 (2) | 0 (0) |

UKCRC, UK Clinical Research Collaboration.

Interim priority setting

There were 1506 respondents to the second survey asking participants to rank their top 10 research priorities from the 114 indicative questions. Respondents (of whom 10% were from black, Asian and minority ethnic groups) to this survey included people living with diabetes and their carers (78%) and healthcare professionals (19%), and participants were drawn from across the UK (File S5b). Indicative questions and their full rankings, reported by participant group, are included in File S6.

The interim priority setting resulted in clear differences in priorities set by people living with diabetes and their carers and healthcare professional respondents: only two of the top 10 ranked questions were common to people living with diabetes and their carers and healthcare professionals groups, identifying the need to give equal weighting to responses from both groups. By selecting the top 10 questions identified by either (or both) people living with diabetes and their carers and healthcare professionals groups, a shortlist of 23 questions was generated. The steering group then discussed the need to support the black, Asian and minority ethnic voice in this priority setting partnership and decided to shortlist questions that were also ranked in the top 10 priorities by black, Asian and minority ethnic respondents, leading to the inclusion of one additional question that was not already included. This left 24 questions in the final shortlist. Most of the top 10 research priorities identified by people living with diabetes and their carers, healthcare professionals and black, Asian and minority ethnic groups fall into the UK Clinical Research Collaboration classification ‘management of disease’ (Table 2). There was no significant difference in how the people living with diabetes and their carers, healthcare professionals and black, Asian and minority ethnic group top 10 priorities fell into UK Clinical Research Collaboration classification groupings (chi‐squared test P = 0.49, df = 7.4).

Table 2.

Percentage of the top 10 research priorities per UK classification theme, presented according to participant group

| UKCRC classification | People living with diabetes and their carers, % | Healthcare professionals, % | Black and minority ethnic groups, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aetiology | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| Prevention and promotion of well‐being | 0 | 9 | 10 |

| Detection, screening and diagnosis | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Development of treatments | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Evaluation of treatments | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Management of disease | 70 | 82 | 70 |

| Health services | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Unclassified | 0% | 0% | 0% |

UKCRC, UK Clinical Research Collaboration.

Chi‐squared test P =0.49, d.f. = 7.4.

Final priority setting

The final workshop for final priority setting was attended by people living with diabetes (n=14), carers (n=4) and multidisciplinary healthcare professionals (n=10), of whom 24% were from black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. The workshop was observed by Diabetes UK representatives (n=4), steering group members (n=4) and representatives from the NIHR (n=2), and facilitated by trained James Lind Alliance advisors (n=3). Following an explanation of how the workshop would be run, the process for prioritizing the 24 questions was explained. The attendees were then allocated to three pre‐arranged discussion groups to ensure a balance in membership. There were four main sessions in which facilitators encouraged all attendees to share their views and supported equal input from the different stakeholder groups. The first session included discussion of pre‐workshop ranking forms; the second was a formal attempt to create a ranking, with the three groups’ results being combined to create a shared ranking. The third session involved participants assigned to different groups to review and revise the shared ranked list. The three groups’ results were again combined, creating a new shared ranked list which was then discussed by the whole group collectively, with a particular focus on agreeing a final shortlist of ‘top 10 research priorities’ (Table 3). Discussion themes within the groups included: how to prioritize disease prevention vs treatment, the need to address both treatment as well as organization of care to deliver treatment, how to ensure the priorities of black, Asian and minority ethnic groups and other seldom‐heard groups are met, perceived ‘labelling’ and ‘stigmatization’ of Type 2 diabetes as a disease, and debate on how to prioritize research into the implementation of interventions (e.g. addressing the training of healthcare professionals) vs research into the effectiveness of the interventions being delivered. The differences in priorities between healthcare professionals and people living with diabetes, as identified in the interim priority setting survey, were discussed and considered by participants when agreeing the final ranking of priorities.

Table 3.

Top 10 research questions agreed as shared priorities, including final rank (after completing all four stages of the priority setting partnership process) and rank at interim prioritization according to target group

| Final rank | Interim priority setting rank | UKCRC classification | What questions about Type 2 diabetes would you like to see answered by research? | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWDC | HCPs | BAME | |||

| 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 | Aetiology | Can Type 2 diabetes be cured or reversed, what is the best way to achieve this and is there a point beyond which the condition can't be reversed? |

| 2 | 73 | 10 | 50 | Prevention | How do we identify people at high risk of Type 2 diabetes and help to prevent the condition from developing? |

| 3 | 62 | 2 | 40 | Management of disease | What is the best way to encourage people with Type 2 diabetes, whoever they are and wherever they live, to self‐manage their condition, and how should it be delivered? |

| 4 | 6 | 28 | 6 | Management of disease | How do stress and anxiety influence the management of Type 2 diabetes and does a positive mental wellbeing have an effect? |

| 5 | 44 | 3 | 14 | Management of disease | How can people with Type 2 diabetes be supported to make lifestyle changes to help them manage their condition, how effective are they and what stops them from working? |

| 6 | 2 | 19 | 10 | Management of disease | Why does Type 2 diabetes get progressively worse over time, what is the most effective way to slow or prevent progression and how can this be best measured? |

| 7 | 20 | 5 | 6 | Management of disease | Should diet and exercise be used as an alternative to medications for managing Type 2 diabetes, or alongside them? |

| 8 | 8 | 40 | 3 | Management of disease | What causes nerve damage in people with Type 2 diabetes, who does it affect most, how can we increase awareness of it and how can it be best prevented and treated? |

| 9 | 75 | 7 | 25 | Management of disease | How can psychological or social support be best used to help people with, or at risk of Type 2 diabetes, and how should this be delivered to account for individual needs? |

| 10 | 13 | 6 | 13 | Management of disease | What role do fats, carbohydrates and proteins play in managing Type 2 diabetes, and are there risks and benefits to using particular approaches? |

BAME, black and minority ethnic groups; HCP, healthcare professional; PWDC, people living with diabetes and their carers; UKCRC, UK Clinical Research Collaboration.

The steering group then gave final consideration to the wording of each of the identified priorities before finalizing them. For example, research priority ‘3’ had previously included the term ‘hard to reach’ (persons) and this was revised to ‘whoever they are and wherever they live’ in response to comments reported from the final workshop which indicated that ‘hard to reach’ was insufficiently inclusive and not acceptable to people living with diabetes.

The steering group and final priority setting workshop attendees discussed the content of research questions where they overlapped, for example, questions 5, 7 and 10. Whilst it was conceivable that overlapping questions could be subsumed into each other, it was felt that the collation of research questions in the pre‐workshop stages of the priority setting partnership process had been effective (reducing 8227 uncertainties into 114 indicative questions by the steering group) and that further combining of questions would have lost their authenticity and that indeed, repeated elements across questions had face value.

It is notable that the final top 10 research priorities identified in the final workshop differed considerably from those ranked at the interim priority settings. The final workshop ‘pulled up’ research question 2 on Type 2 diabetes prevention (included in the final shortlist as it was ranked 10th by healthcare professionals, although was ranked much lower by people living with diabetes and their carers and black, Asian and minority ethnic groups), whereas the top healthcare professional priority at interim shortlisting, ‘What is the most effective approach to weight loss in people with Type 2 diabetes and what factors might affect this?’, was not included in the final top 10. While the interim survey results had been generated by individuals working alone, it is likely that the opportunity provided by the workshop to exchange knowledge and opinions led to a revisions of views, allowing a consensus to emerge.

Dissemination

At the time of writing, the results of this priority setting partnership will be publically announced via a published brief correspondence 20. In addition, Diabetes UK will produce a lay report of the top 10 priorities which will be made available to the public on their website. Going forward, the results will also be presented at various conferences and disseminated to larger funding agencies and other diabetes charities.

Research priorities from both the top 10 and the 114‐question shortlist have been disseminated to the newly formed Diabetes UK Clinical Studies Groups, tasked with creating a strategic roadmap for new research via identification of priority areas and development of focused funding applications.

Discussion

This priority setting partnership, led by Diabetes UK and the James Lind Alliance, brought together over 4000 respondents across two stages of prioritization to identify the ‘top 10 research priorities’ for Type 2 diabetes. The overarching aim and achievement of this priority setting partnership is to bring together people living with Type 2 diabetes, their carers and healthcare professionals to address uncertainties and to prioritize those that require greater research attention. A final list of top 10 research priorities was identified, and included cure and reversal of Type 2 diabetes, identification of risk and prevention, and approaches to self‐management of the condition.

The priority setting partnership followed a rigorous four‐step process predefined by the James Lind Alliance, which was overseen in prespecified and transparent processes by the steering group, and is well replicated across different health conditions and diseases. This process gathered a large number of research priorities from a large and diverse range of respondents. In the first step, gathering uncertainties, we identified 8227 research priorities from people living with Type 2 diabetes, their carers and healthcare professionals. In the second step, these research priorities were classified and collated into 114 ‘indicative questions’ that were taken back, in step 3, to people living with diabetes and their carers and healthcare professionals (n=1506) for them to identify their top 10 priorities. This step led to the shortlisting of 24 research priorities equally weighted to the contributions of people living with diabetes and their carers and healthcare professionals to adequately represent their divergent priorities, and representing black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. The final workshop allowed a frank and thoughtful exchange of views between participants (from all groups) and built consensus to identify the final top 10 priorities. For example, the topic on Type 2 diabetes prevention was second in the final ranking, having been previously ranked 10th, 73rd and 50th by healthcare professionals, people living with diabetes and their carers and black, Asian and minority ethnic groups, respectively. In contrast, the top healthcare professionals’ priority at shortlisting ‘What is the most effective approach to weight loss in people with Type 2 diabetes and what factors might affect this?’ was not included in the final top 10. These changes in ranking after group discussion have been noted previously by other priority setting partnerships, and are underpinned by evidence suggesting that group (compared to individual) decision‐making overcomes biases, uses information more effectively, and finds good solutions 21. Using this methodology, the priority setting partnership was able to represent equitably the views of a wide range of people living with diabetes and their carers and professionals, and to make potential biases explicit. The broad range of experience and expertise in its steering group and the wide and effective reach of Diabetes UK members and its networks facilitated this process. The equitable inclusion of priorities set by people living with diabetes and their carers and healthcare professionals addresses the criticism levelled at the James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership for Type 1 diabetes, that the priorities identified by people living with diabetes and their carers were disadvantaged in discussion over those identified by healthcare professionals 15.

Limitations of this priority setting partnership may include poor representation of some specific groups, such as people living with Type 2 diabetes and end‐stage complications (e.g. blindness, amputations) and or multiple comorbidities, who may have found it difficult to access the questionnaires, and also young people living with the condition. Notably, neuropathy was the only diabetes‐associated complication represented in the final top 10, although other complications do appear in the 114 indicative questions and, as such, their importance and relevance in future research is still highlighted. Relatively low numbers of carers participated in the priority setting partnership (4% of respondents at the first stage of gathering uncertainties), which may have led to low representation of their views. Finally, whilst people living with Type 2 diabetes are able to identify themselves clearly as such, people who are ‘at risk of diabetes’ may be unaware of this risk, leading to underrepresentation and potential bias. Given the breadth of sampling and wide inclusion, however, these limitations are unlikely to be a major bias. Other limitations of the process include the criticism that some of the research priorities raised may represent a failure to articulate or communicate existing research findings, rather than an actual knowledge gap (i.e. they may represent ‘unknown knowns’); however, the steering group was careful to consider all proposed questions and their validity as unanswered research questions and removed 470 questions deemed to be ‘out‐of‐scope’ as they did not reflect true research questions.

This Diabetes UK–James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership for Type 2 diabetes provides an authoritative resource to the academic community and a focus on priority topics that have the potential to bring about a meaningful research impact on people living with Type 2 diabetes and healthcare professionals. Nevertheless, a significant challenge remains to ensure the priority setting partnership findings are taken up by the academic community and influence funding agencies. Priority topics identified through the priority setting partnership may be methodologically challenging for researchers, given their breadth and person‐focused scope; however, the final top 10 questions cover broad topics rather than highly specified research questions and this offers an opportunity for researchers to develop funding proposals that may fit both their expertise and background with the priorities set by the priority setting partnership. Concern that this perspective may detract from prioritization of topics such as basic science underpinning disease aetiology, prevention of Type 2 diabetes, or health service or population‐based approaches to care and prevention, does not seem to have been upheld in the broad scope of the final top 10, which allows interpretation to include all of these topics in the design of research studies.

Diabetes UK has tasked its new strategic Clinical Studies Groups with considering the output of the priority setting partnership in relation to identifying research gaps for future research investment, and by advocacy and promotion of priorities to external funding agencies. Suggestions for specific studies will supplement a wider process of engagement with the academic community, funders and policy‐makers to influence future research prioritization and investment. Researchers who focus their future work on these top 10 priorities will have a strong basis on which to build ongoing public involvement in research and a potential impact on the lives of people living with Type 2 diabetes.

Competing interests

None declared.

Funding sources

Diabetes UK commissioned and funded this programme of work. Andrew Farmer is a NIHR Senior Investigator and receives funding from Oxford BMRC and Chairs the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme General Funding Board.

Supporting information

File S1. Questionnaire.

File S2. Detailed methodology for surveys and workshop.

File S3. MeSH terms and search strategy.

File S4. Respondent characteristics.

File S5. Respondents map, (a) Survey 1, (b) Survey 2.

File S6. Indicative questions.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the large number of people who contributed to the survey and prioritization stages, and participated in the final workshop, as well as those who supported the project, including the National Clinical Director for Obesity and Diabetes at NHS England, Prof. Jonathan Valabhji. The authors acknowledge the work of the Type 2 diabetes Priority Setting Partnership Steering Group in supporting this project to successful completion: Leanne Metcalfe, Independent Facilitator and James Lind Alliance Facilitator (Steering Group Chair, February to August 2016), Katherine Cowan, James Lind Alliance (Chair from September 2016), Paul Robb (has Type 2 diabetes), SF, Martin Jenner (has Type 2 diabetes), Mick Browne, (has Type 2 diabetes), Angelina Whitmarsh (has Type 2 diabetes), Jenny Stevens (has Type 2 diabetes), Sarah Finer, Andrew Farmer, Ali Chakera, Desiree Campbell‐Richards, Ann Daly, Emily Burns (Diabetes UK), Davina Krakov‐Patel (Diabetes UK), Kamini Shah (Diabetes UK), Paul McArdle, Anna Morris (Diabetes UK), Simon O'Neil (Diabetes UK), Krishna Sarda (Diabetes UK), Elizabeth Robertson (Diabetes UK), Ann Daly (information specialist).

Data sharing

The full list of questions/uncertainties raised by survey respondents, and the full list of priorities, identified in the Priority Setting Partnership will be published on the James Lind Alliance website.

Diabet. Med. 35, 862– 870 (2018)

References

- 1. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population‐based studies with 4·4 million participants. Lancet 2016; 387: 1513–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bommer C, Heesemann E, Sagalova V, Manne‐Goehler J, Atun R, Bärnighausen T et al The global economic burden of diabetes in adults aged 20–79 years: a cost‐of‐illness study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017; 5: 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diabetes Prevalence Model . 2016. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/diabetes-prevalence-estimates-for-local-populations. Last accessed 21 August 2017.

- 4. Public Health England . NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme (NHS DPP) Non‐diabetic hyperglycaemia. 2015. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-diabetes-prevention-programme-non-diabetic-hyperglycaemia. Last accessed 26 July 2017.

- 5. Hex N, Bartlett C, Wright D, Taylor M, Varley D. Estimating the current and future costs of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in the UK, including direct health costs and indirect societal and productivity costs. Diabet Med 2012; 29: 855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NICE . Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. Guidance and guidelines. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28. Last accessed 26 July 2017.

- 7. UKCRC . UK Health Research Analysis 2014. Available at http://hrcsonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/UK_Health_Research_Analysis_Report_2014_WEB.pdf Last accessed 6 March 2018

- 8. Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet 2000; 355: 2037–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gross CP, Anderson GF, Powe NR. The Relation between Funding by the National Institutes of Health and the Burden of Disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1881–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chalmers I, Atkinson P, Fenton M, Firkins L, Crowe S, Cowan K. Tackling treatment uncertainties together: the evolution of the James Lind Initiative, 2003–2013. J R Soc Med 2013; 106: 482–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. INVOLVE . Supporting public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. Available at http://www.invo.org.uk/. Last accessed 14 August 2017.

- 12. England, Department of Health . Research Advisory Committee on Diabetes Current and Future Research on Diabetes: a review for the Department of Health and Medical Research Council, London, 2002.

- 13. Brown K, Dyas J, Chahal P, Khalil Y, Riaz P, Cummings‐Jones J. Discovering the research priorities of people with diabetes in a multicultural community: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract 2006; 56: 206–213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gadsby R, Snow R, Daly AC, Crowe S, Matyka K, Hall B et al Setting research priorities for Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2012; 29: 1321–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Snow R, Crocker JC, Crowe S, Rippon H, Holmes K, Firkins L. Missed opportunities for impact in patient and carer involvement: a mixed methods case study of research priority setting. Res Involv Engagem 2015; 1: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. James Lind Alliance . About the James Lind Alliance. Available at http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/about-the-james-lind-alliance/. Last accessed 26 July 2017.

- 17. UKCRC . Health Research Classification System. Available at https://hrcsonline.net. Last accessed 6 March 2018.

- 18. Gallagher M, Hares T, Spencer J, Bradshaw C, Webb I. The Nominal Group Technique: A Research Tool for General Practice? Fam Pract 1993; 10: 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Diabetes Clinical Studies Groups ‐ Diabetes UK] . Available at https://www.diabetes.org.uk/research/our-approach-to-research/clinical-studies-groups. Last accessed 17 August 2017.

- 20. Finer S, Robb P, Cowan K, Daly A, Robertson E, Farmer A. Top ten research priorities for type 2 diabetes: Results from the Diabetes UK‐James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017; 5: 935–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bang D, Frith CD. Making better decisions in groups. R Soc Open Sci 2017; 4: 170193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

File S1. Questionnaire.

File S2. Detailed methodology for surveys and workshop.

File S3. MeSH terms and search strategy.

File S4. Respondent characteristics.

File S5. Respondents map, (a) Survey 1, (b) Survey 2.

File S6. Indicative questions.