Abstract

We developed a quantitative risk assessment model using a discrete event framework to quantify and study the risk associated with norovirus transmission to consumers through food contaminated by infected food employees in a retail food setting. This study focused on the impact of ill food workers experiencing symptoms of diarrhea and vomiting and potential control measures for the transmission of norovirus to foods. The model examined the behavior of food employees regarding exclusion from work while ill and after symptom resolution and preventive measures limiting food contamination during preparation. The mean numbers of infected customers estimated for 21 scenarios were compared to the estimate for a baseline scenario representing current practices. Results show that prevention strategies examined could not prevent norovirus transmission to food when a symptomatic employee was present in the food establishment. Compliance with exclusion from work of symptomatic food employees is thus critical, with an estimated range of 75–226% of the baseline mean for full to no compliance, respectively. Results also suggest that efficient handwashing, handwashing frequency associated with gloving compliance, and elimination of contact between hands, faucets, and door handles in restrooms reduced the mean number of infected customers to 58%, 62%, and 75% of the baseline, respectively. This study provides quantitative data to evaluate the relative efficacy of policy and practices at retail to reduce norovirus illnesses and provides new insights into the interactions and interplay of prevention strategies and compliance in reducing transmission of foodborne norovirus.

Keywords: Discrete event model, microbial risk assessment, norovirus, retail food establishment

1. INTRODUCTION

Noroviruses are often spread through person‐to‐person contact; however, foodborne transmission can cause widespread exposures and presents important prevention opportunities.1 Norovirus is the leading cause of foodborne illness globally and within the United States.2, 3, 4 Restaurants are the most common setting (64%) of food preparation reported in outbreaks in the United States.1 Most foodborne norovirus outbreaks linked to food establishments are traced to contamination of food that is not cooked or otherwise treated before consumption (“ready‐to‐eat” [RTE] food).4, 5, 6, 7

The disease is characterized by a sudden onset of vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps, with a duration of one to three days before reaching a full resolution of symptoms.8 Large numbers of virus are shed in the vomit and stools of infected individuals, primarily during the period of active symptoms, with as much as 1012 genome equivalent copies of norovirus (GEC NoV) per gram of feces in symptomatic individuals with diarrhea,9 and 8 × 105 GEC NoV per milliliter in vomit.10 Duration of viral shedding in adults lasts 20–30 days,11 with a gradual decline in the amount shed during asymptomatic period.12

The lack of availability of a single effective prevention strategy for controlling norovirus has led to the adoption of a combination of prevention strategies used by many jurisdictions.7, 13, 14 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has included a combination of prevention strategies focused on reducing viral contamination of food and surfaces from infected food employees in the FDA Food Code14 and the FDA Employee Health and Personal Hygiene Handbook.15 Current prevention strategies involve the restriction or exclusion of infectious food employees from work, proper hand hygiene, food contact surface (FCS) sanitation, and eliminating barehand contact with RTE food.14

While individual prevention strategies have been studied, the relative impact of each of these strategies, their level of compliance, and the interplay of combinations of these strategies on norovirus transmission in food establishments have not been well studied. This study was conducted specifically to evaluate these impacts on the mean number of contaminated food servings and infected customers. Additional prevention strategies such as increasing the current efficacy of handwashing or preventing hand contact with faucets and doors in the restrooms were also tested to identify effective ways to reduce the risk associated with norovirus in a food establishment.

2. BACKGROUND AND METHODS

2.1. Food Establishment Setting

The model was developed to study the spread of norovirus in a food establishment. A discrete event model was selected as the most suitable model framework to describe the series of consecutive tasks undertaken by food employees. A main advantage of the discrete event model framework is its flexibility, which allows for the inclusion of additional events or the modification of event sequences. This flexibility facilitates comparison of different situations or scenarios such as the impact of new regulations or a change in level of compliance in the quantitative risk assessment.16

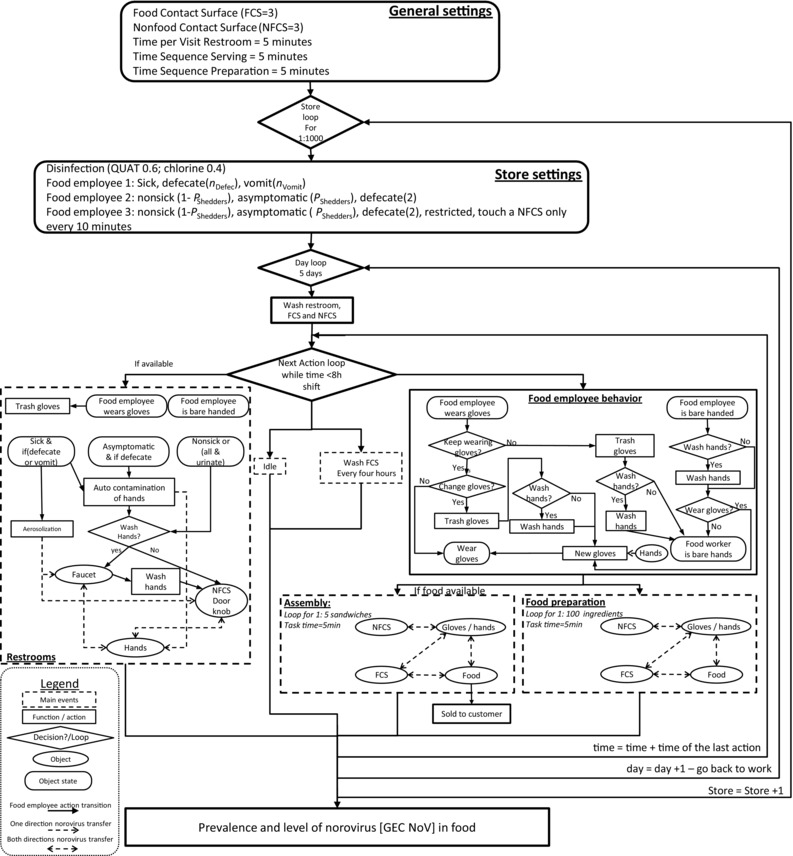

The conceptual model developed is presented in Fig. 1. The shift (work period) of a food employee was represented as a chronological sequence of events occurring at discrete instants in time. The main tasks (events) of the food employees are: (i) prepare food (sequence of five minutes), (ii) assemble food (sequence of five minutes), (iii) wash and sanitize FCS, (iv) use the restrooms, or (v) do nothing (idle). At any time (t), food employees executed one of the five different main events (tasks—dashed rectangle), each task including sequences of actions (e.g., wash hands, change gloves, touch an FCS, etc.) described with function/action, decision/loop, objects, and object states. Solid and dashed arrows represent action transition and norovirus transfer between the objects, respectively.

Figure 1.

General algorithm of the model for the transmission of norovirus in food establishment.

Three employees, referred as FE‐1, FE‐2, and FE‐3, working together during one eight‐hour shift per day for five consecutive days, were considered. FE‐1 and FE‐2 prepared food and touched FCS and nonfood contact surfaces (NFCS), while FE‐3 did not prepare food but sporadically touched NFCS. One type of food, consisting of a three‐item sandwich (e.g., bacon, lettuce, and tomato sandwich), was served to the customers. The two employees FE‐1 and FE‐2 both prepare a total of 200 sandwiches per shift. It is assumed that the food ingredients are initially free of norovirus. The food establishment included two different areas: a food preparation and sandwich assembly area and the restrooms. The food preparation and assembly area included three generic FCS (e.g., knife, cutting board, stainless work surface, etc.) and three generic NFCS (e.g., refrigerator door handle, microwave handle, etc.) (Fig. 1). The restrooms, the FCS, and NFCS were washed and sanitized before the beginning of each shift. The FCS were additionally washed and sanitized every four hours, as recommended by the Food Code.14

2.1.1. Restrooms

The restrooms included three potentially contaminated objects: the door handle, the faucet, and the air environment. The number of visits in the restroom for each employee was related to their health status (symptomatic or not) (Table I) and will be further discussed (Section 2.2). The visits to the restrooms were randomly distributed within the shift. The level of compliance with required handwashing after using the restroom was assumed to be 100% after emesis and 65% and 90% after urination and defecation, respectively.17 Table I describes other parameters regarding the norovirus concentration in feces and vomit, as extracted from the literature.

Table I.

Model Parameter Distributions and Sources

| Input | Definition [Unit] | Distribution | Mean [0.025; 0.5; 0.975 Quantiles] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inputs Associated with Food Employees in the Restrooms | ||||

| VRest | Volume of the restrooms [m3] | cste(12.1) | – | 27 |

| nD | Number of defecations per shift on day 0 of sickness, divided by 2 each day while sick | Poisson(4.5) | 4.5 [1; 4; 9] | 24 |

| Pvomit | Probability that the sick food employee vomits | cste(0.72) | 10 | |

| nV | Number of vomit events per shift minus 1 each day while sick | cste(3) | – | 57 |

| nU | Number of restroom visits to urinate per shift | cste(2) | – | Assumed |

| mH | Mass of feces on hands after defecation [log10 g] | BetaPert(min=−8;mode=−3;max=−1 | −3.5 [−6.17; −3.38; −1.44] | 58, 59 |

| SH | Hand surface [m2] | cste(0.01) | – | 19 |

| VH | Volume of vomit on hands after vomiting events [mL] | cste(10) | – | Assuming 1 mm of vomit on all hand surface SH |

| NoVv | Norovirus concentration in vomit [log10 GEC NoV/mL] | BetaPert(3; 4.5; 7 | 4.67 [3.37; 4.62; 6.16] | 43 |

| NoVsh | Shedding level of food employee [log10 GEC NoV/g] | BetaPert(4; 8; 10 | 7.67 [5.40; 7.74; 9.52] | 9, 60, 61 |

| Dsh | Time to 1 log10 reduction of NoVs in shedding food employees [minutes] (eq. one log10decrease per week) | cste(10,080) | – | 9, 60, 61 |

| TrEnv, d | Aerosol contamination during diarrhea events [NoV/m3] | lognormal(7.6820;0.468) | 2,420 [867; 2,168;5,425] | 27 |

| TrEnv,V | Aerosol contamination during vomit events [GEC Nov/m3] | lognormal(7.6820;0.468)+1,100 | 3,520 [1,967; 3,268; 6,525] | 27, 28 |

| ds | Symptom duration [minutes] | gamma(scale=1.508; rate=0.000513) | 2,940 [218; 2,321; 9,140] (eq. 49 [4, 39, 152] hours) | 24 |

| PWash;H;Rest | Probability of washing hands in the restrooms (vomit, defecate, urinate) | cste(1;0.9; 0.65) | – | 17 |

| Inputs Associated with Food Employees Characteristics and Behavior | ||||

| nHwash;NFH | Number of handwashings per shift for nonfood handling employees | cste(4) | – | Assumed |

| PShedders | Probability of asymptomatic shedders | cste(0.15) | – | 23 |

| Pwear_gloves | Probability of wearing gloves during food preparation (0; .5; .9; 1 of the time) | (0.336; 0.14; 0.12; 0.40) | – | 20 |

| Pchange_gloves | Probability of changing gloves when engaging in food preparation | cste(0.37) | 22 | |

| Pwash;H | Probability of washing hands when engaging in food preparation | cste(0.41) | 22 | |

| Pwash;H | Probability of washing hands while changing gloves | cste(0.30) | 22 | |

| Inputs Associated with Transfer of Norovirus from Surface 1 to Surface 2 (Tr1;2) | ||||

| TrH;S | Norovirus transferred from hand to surface | inv.logit(normal(−3.82,ResTrans)) | 0.02 [4.61×10−4; 0.02; 0.51] | Meta‐analysis: 51, 52, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69 |

| TrS;H | Norovirus transferred from surface to hand | inv.logit(normal (0.11,ResTrans)) | 0.53 [2.30×10−2; 0.53; 0.98] | |

| TrG;S | Norovirus transferred from glove to surface | inv.logit(normal (−2.14,ResTrans)) | 0.11 [2.47×10−3; 0.11; 0.85] | |

| TrS;G | Norovirus transferred from surface to glove | inv.logit(normal (−1.34,ResTrans)) | 0.21 [5.48×10−3; 0.21; 0.93] | |

| TrF;H | Norovirus transferred from food (nonmeat) to hand | inv.logit(normal (−3.86,ResTrans)) | 0.02 [4.43×10−4; 0.02; 0.50] | |

| TrH;F | Norovirus transferred from hand to food (nonmeat) | inv.logit(normal (−2.95,ResTrans)) | 0.05 [1.10×10−3; 0.05; 0.71] | |

| TrFm;H | Norovirus transferred from food (meat) to hand | inv.logit(normal (−2.62,ResTrans)) | 0.07 [1.53×10−3; 0.07; 0.78] | |

| TrH;Fm | Norovirus transferred from hand to food (meat) | inv.logit(normal (−0.034,ResTrans)) | 0.49 [0.02; 0.49; 0.98] | |

| TrF;G | Norovirus transferred from food (nonmeat) to glove | inv.logit(normal (0.90,ResTrans)) | 0.71 [0.05; 0.71; 0.99] | |

| TrG;F | Norovirus transferred from glove to food (nonmeat) | inv.logit(normal (−0.82,ResTrans)) | 0.31 [0.01; 0.31; 0.95] | |

| TrFm;G | Norovirus transferred from food (meat) to glove | inv.logit(normal (−0.13,ResTrans)) | 0.47 [0.02; 0.47; 0.98] | |

| TrG;Fm | Norovirus transferred from glove to food (meat) | inv.logit(normal (−0.29,ResTrans)) | 0.43 [0.02; 0.43; 0.97] | |

| TrF;S | Norovirus transferred from food (nonmeat) to surface | inv.logit(normal (−2.82,ResTrans)) | 0.06 [1.25×10−3; 0.06; 0.74] | |

| TrS;F | Norovirus transferred from surface to food (nonmeat) | inv.logit(normal (0.87,ResTrans)) | 0.70 [0.05; 0.70; 0.99] | |

| TrFm;S | Norovirus transferred from food (meat) to surface | inv.logit(normal (−0.94,ResTrans)) | 0.28 [0.01; 0.28; 0.95] | |

| TrS;Fm | Norovirus transferred from surface to food (meat) | inv.logit(normal (4.45,ResTrans)) | 0.99 [0.64; 0.99; 1.00] | |

| TrH;G | Norovirus transferred from hand to glove | inv.logit(normal (−2.78,ResTrans)) | 0.06 [1.30×10−3; 0.06; 0.75] | |

| ResTrans | Residuals of the meta‐analysis for transfer | cste(1.97) | – | |

| Meta‐analysis: | ||||

| DWH | Handwashing efficiency [log10 NoV] | BetaPert(0.17;0.45;6; shape=4) | 1.33 [0.23; 1.13; 3.47] | 55, 56, 58, 62, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81 |

| Inputs Associated with Survival of Norovirus on Surfaces | ||||

| DH | Time to 1 log reduction of GEC NoV on hands [minutes] | lognormal(6.50;ResSurv) | 1,154 [85; 665; 5,208] (eq.: 19 [1, 11, 87] hours) | Meta‐analysis: 63, 64, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95 |

| DS | Time to 1 log reduction of GEC NoV on hard surface [minutes] | lognormal(10.17; ResSurv) | 45,309 [3,334; 26,108; 204,426] (eq.: 755 [56, 435,3407] hours) | |

| DG | Time to 1 log reduction of GEC NoV on gloves [minutes] | lognormal(11.02; ResSurv) | 106,006 [7,801; 61,083; 478,285] (eq.: 1,766 [130, 1,018,7,971] hours) | |

| DF | Time to 1 log reduction of GEC NoV on food [minutes] | lognormal(9.57; ResSurv) | 24,866 [1,829; 14,328; 112,191] (eq.: 414 [30, 238, 1,870] hours) | |

| ResSurv | Residuals of the meta‐analysis for survival | cste(1.05) | – | |

| Inputs Associated with Disinfection | ||||

| Pdis | Probability of using a type of disinfectant in store (quaternary ammonium; chlorine) | (0.6;0.4) | – | |

| DisS;QUAT | GEC NoV reduction due to disinfection of hard surfaces with quaternary ammonium | log10(inv.logit(norm(−3.44, ResDis)) | −1.51 [−4.55; −1.51; −0.01] | Meta‐analysis: 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 85, 93, 94, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105 |

| DisS;QUAT | GEC NoV reduction due to disinfection of hard surfaces with chlorine | log10(inv.logit(norm(−6.02, ResDis)) | −2.61 [−5.67; −2.61; −0.13] | |

| DisS;QUAT | GEC NoV reduction due to disinfection of hands with quaternary ammonium | log10(inv.logit(norm(−6.16, ResDis)) | −2.67 [−5.73; −2.67; −0.15] | |

| DisS;QUAT | GEC NoV reduction due to disinfection of hands with chlorine | log10(inv.logit(norm(−8.74, ResDis)) | −3.80 [−6.85; −3.80; −0.81] | |

| ResDis | Residuals of the meta‐analysis for disinfection | cste(3.59) | ||

Cste: constant; BetaPert: betapert distribution with shape parameter 430; X ∼ lognormal(a, b) if ln(X) ∼ normal(mean=a, SD=b); inv.logit(x) = exp(x)/(1+exp(x)).

2.1.2. Food Preparation/Sandwich Assemblage

Food preparation and sandwich assemblage sequences were adapted from Mokhtari et al.18 and Stals et al.19 The food preparation and sandwich assemblage were considered to be two distinct events. We assumed that the food ingredients (e.g., lettuce, tomato, and bacon) were first prepared (e.g., sliced) by batch, and later assembled to make sandwiches. The objects and actions initiated during the assemblage and preparation events were similar (Fig. 1). First, an FCS for food preparation/assembly was randomly assigned to the employee. Then for each ingredient, contacts between FCS, gloves/hands, or food occurred twice in a random sequence. Contact with NFCS occurred once during each random sequence. Food employees prepared 20 pieces of one ingredient per minute (e.g., sliced 20 tomato slices). An additional cooking step was included for one of the ingredients (e.g., bacon), eliminating any norovirus present on this ingredient at the time. A pace of one sandwich assembled per minute was considered. If at least one type of food ingredient was not available, a sandwich could not be assembled; the food employee would instead prepare this type of ingredient and then return to sandwich preparation.

2.1.3. Food Employee Practices

The behavior of food employees was included in the model using data from surveys.17, 20, 21, 22 Frequency of handwashing when engaging in food preparation was based on data from CDC,22 which reported that food employees washed their hands in 27% of activities in which they should have. Regarding glove‐use frequency when touching RTE food (Table I), food employees reported that they never (33%), sometimes (6%), almost always (14%), or always (40%) wore gloves. Food employees changed gloves 37% of the time when engaging in food preparation, based on a CDC report.21 We note that use of food contact utensils such as spatulas or tongs instead of gloves were not modeled because of limitations in data on the frequency of use and efficiency of transfer to and from these objects.

Some individuals infected with norovirus will develop asymptomatic infection, while others will develop symptoms of vomiting and diarrhea. In the model, two food employees (FE‐2 and FE‐3) were not sick but had an independent probability to be asymptomatic shedders of 15%.23 Only one employee (FE‐1) was assumed to be symptomatic. The duration of the symptoms was modeled using a gamma distribution so that the mean duration was 49 hours with a standard deviation of 40 hours.24 We assumed that a symptomatic food employee (FE‐1) always experienced diarrhea. The number of defecations per day was assumed to be 4.5 on average per shift at the onset of the symptoms,24 and this average was reduced by two each day until the end of the symptomatic illness. Seventy‐two percent of symptomatic cases experienced vomiting,10 with three vomiting events on the first day, two vomiting events on the second day, and one vomiting event on the third day, if still sick. Other parameters regarding the concentration of norovirus in feces and vomit are described in Table I.

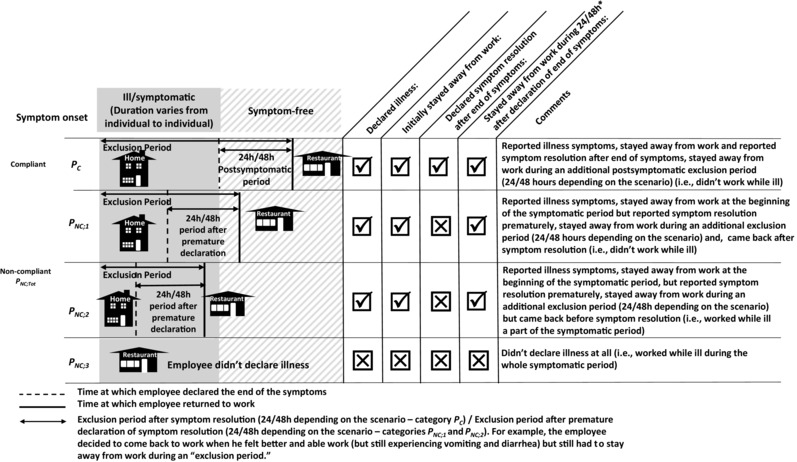

In order to protect consumers from symptomatic food employees that may have an undiagnosed norovirus infection (which represent the majority of norovirus cases since most will not be specifically diagnosed), the FDA Food Code recommends an exclusion period of food employees from work when they are experiencing vomiting and/or diarrhea symptoms and for at least 24 hours after the symptoms resolve in the absence of confirmation of the norovirus infection.14 However, food employees do not always comply with this exclusion period. Surveys have shown that, for various reasons, some food employees have worked while ill.25 A survey by Sumner et al.26 reported that 20% of food employees declared having experienced vomiting or diarrhea while working during the year preceding the interview. We included a rate of compliance Pc in the model to account for ill employees (FE‐1) who reported illness and complied with the exclusion period and food employees who did not report or did not comply with the exclusion period and may have worked while ill. We considered that FE‐1 was ill and could belong to four categories (“compliant,” “noncompliant 1,” “noncompliant 2,” and “noncompliant 3”) to accurately represent compliance with the exclusion guidance, as presented in Fig. 2:

Compliant ill food employee: Reported illness symptoms, stayed away from work and reported symptom resolution after end of symptoms, stayed away from work during an additional postsymptomatic exclusion period (24/48 hours depending on the scenario) (i.e., did not work while ill).

Noncompliant ill food employee; type 1 (“noncompliant 1”): Reported illness symptoms, stayed away from work at the beginning of the symptomatic period but reported symptom resolution prematurely, stayed away from work during an additional exclusion period (24/48 hours depending on the scenario) and came back after symptom resolution (i.e., did not work while ill).

Noncompliant ill food employee; type 2 (“noncompliant 2”): Reported illness symptoms, stayed away from work at the beginning of the symptomatic period, but reported symptom resolution prematurely, stayed away from work during an additional exclusion period (24/48 hours depending on the scenario) but came back before symptom resolution (i.e., worked while ill a part of the symptomatic period).

Noncompliant ill food employee; type 3 (“noncompliant 3”): Did not declare illness at all (i.e., worked while ill during the whole symptomatic period).

Figure 2.

Graphical illustration of food employee behavior regarding declaration of illness/symptom resolution and compliance with the exclusion period. Note that the duration of the sickness (from symptom onset to symptom resolution) varies from one simulation to the other in the model.

Each category is represented by a proportion with:

| (1) |

where PNC is the proportion of noncompliant food employees, PC is the proportion of compliant food employees, and PNC;i is the proportion of noncompliant food employees of type i. We assumed that the category “noncompliant 3” represented 50% of the proportion of total noncompliant:

| (2) |

Food employees of categories “noncompliant 1” and “noncompliant 2” declared premature symptom resolution within 24 hours after symptom onset, according to a uniform distribution Uniform(0;24)(hours), with an average of 12 hours. The values of PNC;2 and PNC;3 are determined from the exclusion period time and the cumulative function of the gamma distribution of symptom duration. For an exclusion period of 24 hours, food employees will come back to work at time 12 + 24 = 36 hours on average. According to the gamma distribution used to model the duration of symptoms, the symptoms are resolved for 46% of food employees at 36 hours. Then:

| (3) |

where pasymp;36h = 0.46 is the proportion of asymptomatic food employees at t ≥ 36 hours according to the considered gamma distribution and

| (4) |

This dynamic of symptomatic illness leads to a reduction of symptoms (diarrhea, vomiting) with time, and thus as a function of the exclusion period. As an example, for an extended exclusion period of 48 hours, food employees will come back to work at time 12 + 48 = 60 hours on average and pasymp;60h = 70%.

2.2. Norovirus Transfer in the Retail Environment

2.2.1. Sources of Contamination

Initial transfer of norovirus from infected food employees to the retail environment takes place in the restrooms via defecation (symptomatic and asymptomatic food employees) and vomiting events (symptomatic food employees). Hand contamination during defecation was considered for symptomatic and asymptomatic food employees. The level of norovirus on hands NoVH after defecation and vomit were calculated using:

| (5) |

| (6) |

where NoVSh is the level of norovirus shed by the food employee at that time, mH is the mass of feces on hands, NoVV is the level of norovirus in vomit, and VH the volume of vomit on hands after vomit.

In addition, for symptomatic employees, norovirus aerosolization within restrooms, and subsequent contamination of the environment (NoVEnv,t=0) within the restrooms, was considered for toilet flushing of diarrheal events and during vomiting, using data extracted from Barker et al.27 and Tung‐Tompson et al.,28 respectively.

| (7) |

| (8) |

where VR is the restroom volume and TrEnv;d and TrEnv;V are the transfer rate of norovirus to the restroom environment during diarrheal and vomiting events, respectively. The aerosol contaminated the door handle and the faucet handle through sedimentation of suspended norovirus on those surfaces. A sedimentation rate of 1 log10 of norovirus per Dsed = 30 minutes is used in the model.27 The total amount of norovirus during a sedimentation time (minutes) was simulated with:

| (9) |

The amount of norovirus on the faucet handle NoVf was calculated using a binomial distribution:

| (10) |

where Sf is the surface of the faucet handle (assumed equal to the hand surface SH) and SR is the surface of the restrooms. The same methodology was used for the contamination of the door handle. Self‐contamination of hands and transfer between hands, faucet, and door handle were also considered (Table I).

2.2.2. Norovirus Transfer and Survival

For each physical contact between two objects/surfaces, the quantities of norovirus transferred from surface S1 to surface S2, , and from surface S2 to surface S1, , were calculated using a binomial distribution:

| (11) |

| (12) |

where NoVS1;t and NoVS2;t are the respective levels of norovirus on surface S1 and S2 at the time t of the contact and TrS1;S2 is the transfer probability of norovirus. The levels of norovirus NoVS1;t+1 and NoVS2;t+1 on surfaces S1 and S2 after the contact were calculated with:

| (13) |

| (14) |

The survival on surfaces during a time step was calculated using a log linear reduction model:

| (15) |

where Δt (minutes) is the time step and DS1 is the time (minutes) for a 1 log10 reduction of norovirus on the surface S1.

The level of norovirus after disinfection of the surface S1 was calculated with:

| (16) |

where Dis is the norovirus reduction due to disinfection. Removal of norovirus from hands by handwashing is defined similarly with:

| (17) |

2.3. Data Sources

A meta‐analysis was conducted to collect data from peer‐reviewed articles for survival, transfer, handwashing, and disinfection through the online libraries PubMed and Web of Science in field tags “titles and abstracts” and using the Boolean logic {(norovirus OR norovirus surrogates) AND (inactivation OR persistence OR survival OR disinfection OR transfer OR wash)}. A total of 846 abstracts were studied, and 330 articles were screened according to the relevance of the abstract. Articles were selected for transfer from surface to surface (10 articles), persistence on surfaces (16 articles), handwashing (16 articles), and disinfection (18 articles) based on the quality of the data, the validity of the surrogates, and the methodology.

The inclusion criteria included a variety of surrogate viruses. These surrogates have been extensively described in the literature as having similar properties with norovirus as far as some of their morphological, cultural, genetic, and structural characteristics. In addition to norovirus genogroup I (GI) and genogroup II (GII), the surrogates used were the feline calicivirus (FCV F9 or KS20), murine norovirus (MNV‐1 or MNV99), and the most recently discovered Tulane virus (TV). Additionally, nontraditional surrogates outside the calicivirus family, such as rotavirus, poliovirus, hepatitis A virus, or even nonanimal viruses like F‐specific RNA coliphage MS2, were also included for certain studies. Particularly, the transfer and handwashing analysis data were supplemented with those from other viruses as these events are mainly physical and assumed independent of the physiology of each particular virus.

Detection through reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) is currently the only method to quantify norovirus titer, which is expressed in terms of genomic copies, or genome equivalents (RNA copies or transcripts if they were generated by real‐time system or just RT‐PCR amplifiable units for conventional platforms). Data for both norovirus genogroups GI and GII were extracted, where available, but not reported separately. For all the surrogate viruses, as they are all culturable, data generated by both RT‐PCR detection and infectivity assays (plaque assay and TCID50) were extracted. All data were expressed as genomic copy equivalents of norovirus (GCE NoV) as, currently, there are no infectivity data available for norovirus. Publications that did not adequately describe methodologies and did not include controls to justify any heterogeneity among the test viruses were excluded. Regarding disinfection, only disinfectants typically used in food service (i.e., quaternary ammonium and sodium hypochlorite) were included.

Additional information on the data collected for the meta‐analysis and fitted models is presented in Table II. Models were fitted using fixed and mixed effects linear models. The specific study from which a set of data was collected was used as a random effect in mixed models. Models were compared using the F‐test (95% confidence interval) or likelihood ratio test when nested. When two models were not nested, the Akaike information criterion (AIC)29 was used to select the preferred one. Besides handwashing, for which a BetaPert distribution30 was fitted, mixed effect models were preferred to fixed effect models because of the nonnegligible impact of the study effect (results not shown). Moreover, mixed effect models allow generalizing the results to a population of studies that were not included in the analysis.31 The factors resulting from the meta‐analysis and used in the model to predict transfer, disinfection, handwashing, and survival of norovirus are shown in Table I.

Table II.

Details of the Meta‐Analyses

| Considered Independent Variables | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta‐Analysis (Number of Selected Articles/Observations) | Dependent Variablea | Virus and Surrogates | Method | Type of Surface | Surface Characteristic | Temperature | Disinfectant | Model | Model Normalization |

| Transfer (10/420 data points) | TrS1;S2 | Norovirus(GI, GII), FCV, MNV1, MS2, Tulane, HAV | Plaque assay Real‐time RT‐PCR | Hard surface, hand, glove, nonmeat food, meat | Wet, dry | NA | NA | Mixed effect | for GEC NoV at: Wet, real‐time RT‐PCR, NoV |

| Persistence (16/138 curves) | DS | Norovirus (GI, GII), FCV, MNV1, MS2, Tulane, MS2 | Plaque assay Real‐time RT‐PCR | Hard surface, hand, gloves, nonmeat food, meat | NA | Refrigerated, room | NA | Mixed effect | for GEC NoV at: Room temperature and real‐time RT‐PCR |

| Disinfection (18/249 data points) | Dis | Norovirus (GI, GII), FCV, MNV1, MNV99, MS2, Tulane | Plaque assay Real‐time RT‐PCR TCID50 | Hard surface | Wet, dry | NA | Quaternary ammonium, chlorine | Mixed effect | for GEC NoV at: Wet, real‐time RT‐PCR, NoV |

| Handwashing (16/50 data points) | DWH | Norovirus (GI, GII), FCV, MNV1, MNV99, MS2, Tulane, HAV, Rotavirus, Poliovirus | Plaque assay Real‐time RT‐PCR TCID50 | Hand | NA | NA | NA | BetaPert (0.17;0.45;6; shape=4) | NA |

See Table I. FCV: Feline calicivirus, MNV: murine norovirus, MS2: F‐specific RNA coliphage MS2, Tulane: Tulane virus, HAV: hepatitis A virus, NA: nonavailable.

2.4. Customer Probability of Infection

A dose–response model was used to evaluate the number of infected customers and the number of illnesses resulting from the consumption of prepared sandwiches in the population. Teunis et al.32 developed a dose–response model for norovirus from experimental infection data. For a discrete number of norovirus, as considered in the model, this dose–response model can be written:33

where Γ(x) is the gamma function, NoVi is the number of ingested norovirus, α = 0.040, and β = 0.055. These parameters were estimated for a susceptible (positive secretor, Se+) population. The probability of illness given infection for an Se+ individual at random ingesting NoVi norovirus is:

where r = 2.55 × 10−3 and η = 0.086 from Teunis et al.32 We considered that 80% of the population was Se+ and that the remaining population was fully resistant to the infection.34

As an alternative to the estimate of number of infected and sick customers, we provide the proportion of servings including more than 0, 100, and 1,000 GEC NoV as an indicator of the potential of norovirus infection from consumption of sandwiches by a susceptible population prepared in the setting.

2.5. Baseline and Scenarios

A total of 22 scenarios describing specific prevention strategies (Table III) and presented in Table IV were compared to evaluate the impact of model parameters on the risk of illness associated with norovirus contamination of foods served in this setting.

Table III.

Overview of the Prevention Strategies and Factors Studied

| Preventive Strategy | Factors | Scenariosa |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusion period from work (time to stay away from work while symptomatic and after declaration of symptom resolution) | Duration (symptomatic period + 24 hours after symptom resolution, symptomatic period + 48 hours after symptom resolution) and compliance | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 15, 17 |

| Restroom cleaning | Frequency | 10 |

| No hand contact with faucet and door in restrooms | – | 13 |

| Restriction from food preparation area, no contact with food | Duration (24 hours, 48 hours) | 14, 15, 16, 17 |

| No barehand contact with food (using gloves in food preparation area) | Frequency (wear and change, compliance according to Food Code when engaging in food preparation) | 11, 18 |

| Handwashing | Frequency (compliance in restrooms and before engaging in food preparation and while changing gloves) and efficacy | 12, 18, 19, 20 |

All details of scenarios are described in Table III. All scenarios are to be compared with scenario 1 (baseline) representing existing knowledge of current practices and food employee behavior in retail food establishment.

Table IV.

Scenarios

| # | Descriptions of the Scenario | Compliance with Exclusion Time Pc/P NC;1/P NC;2 /P NC;3 (%) | Exclusion Period after Symptom Resolution | Compliance with Exclusion | Compliance with Handwashing in Restrooms | Compliance with Handwashing When Engaging in Food Preparation | Compliance with Wear Gloves When Engaging in Food Preparation | Compliance with Change Gloves When Engaging in Food Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline Scenario: FE‐1 is ill, FE‐2 and FE‐3 are asymptomatic shedders in 15% of the stores. Restrooms and NFCS are washed before shift each day. FCSs are washed every four hours. Current practices regarding level of compliance with exclusion from work of 24 hours after symptom resolution + current practice with regard to level of compliance with handwashing in restrooms, handwashing when engaging in food preparation, and glove use when engaging food preparation.a | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Currenta | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 2 | Baseline + no ill food employees, FE‐1, FE‐2, and FE‐3, are asymptomatic shedders in 15% of the stores. | – | – | – | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 3 | Baseline + no compliance with exclusion from work (all sick employees work while ill, PNC;3 = 100%). | 0 / 0 / 0 / 100 | – | None | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 4 | Baseline + full compliance with exclusion from work while symptomatic and for 24 hours after symptom resolution. | 100 / 0 / 0 / 0 | 24 hours | Full | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 5 | Baseline + full compliance with exclusion from work while symptomatic and for 48 hours after symptom resolution. | 100 / 0 / 0 / 0 | 48 hours | Full | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 6 | Baseline + exclusion from work of 48 hours after symptom resolution. | 74 / 9.1 / 3.9 / 13 | 48 hours | Current | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 7 | Baseline + slight decreased compliance with exclusion from work while symptomatic and for 48 hours after symptom resolution. | 64 / 12.6 / 5.4 / 18 | 48 hours | Decreased | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 8 | Baseline + significant decreased compliance with exclusion from work while symptomatic and for 48 hours after symptom resolution. | 54 / 16.1 / 6.9 / 23 | 48 hours | Decreased | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 9 | Baseline + increased compliance with exclusion from work while symptomatic and for 24 hours after symptom resolution. | 84 / 3.7 / 4.3 / 8 | 24 hours | Increased | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 10 | Baseline + restrooms washed every four hours. | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Current | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 11 | Baseline + employees always wearing gloves without necessarily changing gloves. | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Current | Current | Current | Full | Current |

| 12 | Baseline + employees always wash their hands in the restrooms. | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Current | Full | Current | Current | Current |

| 13 | Baseline + touchless faucet and door handles in restrooms. | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Current | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 14 | Baseline + FE‐3 replacing FE‐1, FE‐1 is excluded from the food preparation area (no contact with food and FCS, contact with NFCS every 10 minutes) during 24 hours, FE‐1 is not replaced when he does not declare illness at all (category noncompliant 3). | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Current | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 15 | Baseline + 48‐hour exclusion after symptom resolution + FE‐3 replacing FE‐1, FE‐1 is excluded from the food preparation area (no contact with food and FCS, contact with NFCS every 10 minutes) during 24 hours, FE‐1 is not replaced when he does not declare illness at all (category noncompliant 3). | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 48 hours | Current | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 16 | Baseline + FE‐3 replacing FE‐1, FE‐1 is excluded from the food preparation area (no contact with food and FCS, contact with NFCS every 10 minutes) during 48 hours, FE‐1 is not replaced when he does not declare illness at all (category noncompliant 3). | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Current | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 17 | Baseline + full compliance with exclusion from work + FE‐3 replacing FE‐1, FE‐1 is excluded from the food preparation area (no contact with food and FCS, contact with NFCS every 10 minutes) during 24 hours, FE‐1 is not replaced when he does not declare illness at all (category noncompliant 3). | 100 / 0 / 0 / 0 | 24 hours | Current | Current | Current | Current | Current |

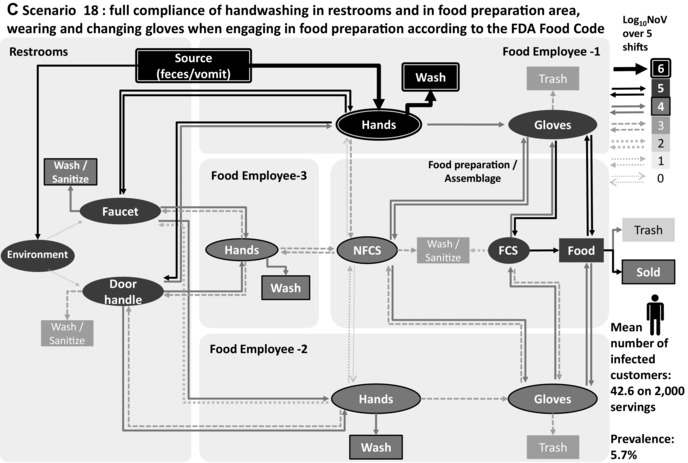

| 18 | Baseline + full compliance of handwashing in restrooms + full compliance with handwashing in food preparation area, wearing and changing gloves when engaging in food preparation according to the FDA Food Code. | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Current | Full | Full | Full | Full |

| 19 | Baseline + improved handwashing efficacy (+1 log10). | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Current | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 20 | Baseline + improved handwashing efficacy (+2 log10). | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Current | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 21 | Baseline + considering all food employees who worked while symptomatic are noncompliant type 3 (i.e., all come to work during the whole symptomatic period). | 80 / 0 / 0 / 20 | 24 hours | Equivalentb | Current | Current | Current | Current |

| 22 | Baseline + considering all food employees who worked while symptomatic are noncompliant type 3 (i.e., come to work during the whole symptomatic period) + exclusion from work of 48 hours after symptom resolution. | 80 / 0 / 0 / 20 | 48 hours | Equivalentb | Current | Current | Current | Current |

Current: Based on observational surveys; see Table I for the value of parameters; –: not used.

In the baseline and in scenarios 21 and 22, 20% of food employees came to work while symptomatic and 80% came to work after symptom resolution. In the baseline, categories PNC;2 (7%) and PNC;3 (13%) came to work while symptomatic (7+13=20%), and categories PC (74%) and PNC;1 (6%) came back to work after symptom resolution (74 + 6 =80%).

Scenario 1 is the baseline of this study in the sense that it represents existing knowledge of current practices and food employee behavior in food establishments. FE‐1 was ill and belonged to categories “compliant,” “noncompliant 1,” “noncompliant 2,” and “noncompliant 3” in 74%, 6.0%, 7.0%, and 13% of simulated stores, respectively. FE‐2 and FE‐3 were asymptomatic shedders in 15% of the stores. Restrooms, NFCS, and FCS were washed every morning before the beginning of the shift. FCS were washed every four hours. Current practices based on existing knowledge were used to describe the frequency of handwashing in restrooms, and the frequency of handwashing, wearing, and changing of gloves when engaging in food preparation (Table I).

A scenario in which FE‐1 was not ill (but could be asymptomatic shedder as FE‐2 and FE‐3; scenario 2—lower baseline) and a scenario in which FE‐1 systematically worked while ill during the whole symptomatic period (scenario 3—upper baseline) were included.

The 19 other scenarios were variations around the baseline to test the impact of different parameters of the model corresponding to specific prevention strategies and their compliance to reduce norovirus transmission (Tables III and IV). The impacts of extending the exclusion period after symptom resolution from 24 to 48 hours and associated compliance with this exclusion period was studied in scenarios 4–9. The impacts of the frequency of handwashing in restrooms (scenario 10), no barehand contact (scenario 11), compliance with handwashing and glove use when engaging in food preparation according to the Food Code recommendation (scenario 18), and handwashing efficacy were also studied (scenarios 18 and 19). The impact of food employee restriction was also evaluated (scenarios 14–17).

2.6. Implementation of the Model

This model was written in the open‐source language R version 3.2.4 (R Core Team).35 In view of the numerous scenarios and the discrete event framework of the model, the code was written to be launched on parallelized processors using high‐performance computing tools (Office of Science and Engineering Laboratories, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, FDA, Silver Spring, MD, USA). Nonetheless, the code can be run on a desktop. For each tested scenario, 1,000 stores in which the actions of the employees are different were simulated. The model was vectorized to simulate 1,000 independent teams of three food employees for each of the 1,000 stores, each team doing the same events at the same time, but, for example, with different transfer coefficients or handwashing efficacy, for each of the 1,000 stores, resulting in a total of 1,000,000 simulated stores. Variability in (asymptomatic) infection of FE‐2 and FE‐3, in different transfer coefficients sampled at each contact, as well as the probability to wear gloves and wash hands was considered for each food establishment team. A thousand stores serving 400 sandwiches per day during five days were studied. The total number of servings for each of the 22 scenarios is 2 × 109. The convergence of all output was checked graphically.

The code is available on request to the corresponding author.

3. RESULTS

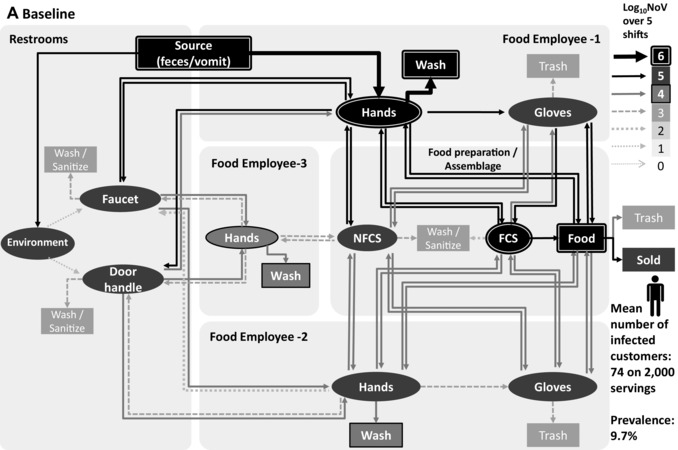

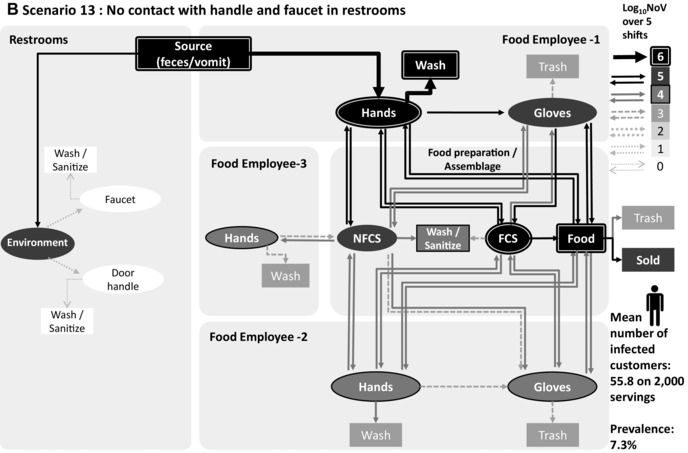

The proportion of contaminated servings (prevalence), the proportion of highly contaminated servings (>100 and >1,000 GEC NoV), and the mean number of infected and ill customers (according to the Teunis et al.32 dose response model) for each of the 22 scenarios are presented in Table V. The estimated mean number of infected customers and the proportion of highly contaminated servings (>1,000 GEC NoV) for each scenario were normalized to the scenario 1 (baseline of this study), to provide a relative measure. In addition to the mean, the 90% variability interval, i.e., the 5th and 95th percentiles of the distribution of the number of infected and sick customers over 1,000,000 stores, is presented in Table V. Fig. 3 illustrates model results on the relative amount of norovirus transmitted via each pathway in the model for three representative scenarios.

Table V.

Simplified Description and Results of the Scenarios (Scenario 1 Is Considered as the Baseline)

| Proportion of Servings (%) with | Number of (on 2,000 Servings) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Compliance with Exclusion Period Pc/PNC ;1/PNC ;2 /PNC ;3 (%) | Exclusion Period after Symptom Resolution | Simplified Description of the Scenario | > 0 NoV | > 100 NoV | > 1,000 NoV | Infected Customers, Mean [90% Variability Interval] | Sick Customers, Mean [90% Variability Interval] | %Baseline Number of Infected Customers | %Baseline Number of Servings >1,000 |

| 1 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Baseline | 9.7 | 1.7 | 0.54 | 74.0 [2.1, 233.7] | 1.7 [0.0, 7.9] | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | – | – | FE‐1 not sick, 15% asymptomatic shedder (lower baseline) | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 9.6 [0.0, 61.0] | 0.1 [0.0, 0.4] | 13 | 7 |

| 3 | 0 / 0 / 0 / 100 | – | FE‐1 always work while ill (upper baseline) | 21.5 | 4.9 | 1.76 | 167.4 [29.0, 357.7] | 5.2 [0.1, 17.2] | 226 | 324 |

| 4 | 100 / 0 / 0 / 0 | 24 hours | Full exclusion compliance, 24 hours | 7.4 | 1.0 | 0.31 | 55.8 [1.4, 176.4] | 1.0 [0.0, 4.8] | 75 | 58 |

| 5 | 100 / 0 / 0 / 0 | 48 hours | Full exclusion compliance, 48 hours | 6.8 | 0.9 | 0.26 | 51.2 [1.1, 165.5] | 0.8 [0.0, 4.1] | 69 | 48 |

| 6 | 74 / 9.1 / 3.9 / 13 | 48 hours | Exclusion extension | 8.9 | 1.5 | 0.47 | 67.9 [1.7, 222.8] | 1.5 [0.0, 7.1] | 92 | 87 |

| 7 | 64 / 12.6 / 5.4 / 18 | 48 hours | Exclusion extension, slight decrease in compliance | 9.7 | 1.7 | 0.55 | 74.2 [1.8, 240.3] | 1.7 [0.0, 8.1] | 100 | 101 |

| 8 | 54 / 16.1 / 6.9 / 23 | 48 hours | Exclusion extension, significant decrease in compliance | 10.5 | 1.9 | 0.63 | 80.5 [2.1, 255.1] | 1.9 [0.0, 9.1] | 109 | 116 |

| 9 | 84 / 3.7 / 4.3 / 8 | 24 hours | Improved compliance | 8.7 | 1.4 | 0.45 | 66.3 [1.8, 211.6] | 1.4 [0.0, 6.6] | 90 | 82 |

| 10 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Wash restrooms every four hours | 9.4 | 1.6 | 0.53 | 71.7 [2.1, 225.4] | 1.6 [0.0, 7.7] | 97 | 98 |

| 11 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | No barehand contact, 100% wear gloves, current compliance with changing gloves | 11.1 | 1.7 | 0.49 | 84.1 [1.4, 266.9] | 1.6 [0.0, 7.8] | 114 | 91 |

| 12 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Full handwashing compliance in restrooms, 100% wash hands in restrooms | 9.2 | 1.5 | 0.48 | 69.9 [1.7, 223.7] | 1.5 [0.0, 7.2] | 94 | 89 |

| 13 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Touchless faucet and door in restroom | 7.3 | 1.3 | 0.46 | 55.8 [0.7, 191.3] | 1.4 [0.0, 6.8] | 75 | 85 |

| 14 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Food handling restriction, FE‐3 replaces FE‐1 during 24 hours | 10.1 | 1.7 | 0.56 | 77.0 [2.1, 237.3] | 1.7 [0.0, 8.2] | 104 | 103 |

| 15 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 48 hours | Food handling restriction, FE‐3 replaces FE‐1 during 24 hours | 9.3 | 1.5 | 0.48 | 70.5 [1.7, 225.8] | 1.5 [0.0, 7.3] | 95 | 89 |

| 16 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Food handling restriction, FE‐3 replaces FE‐1 during 48 hours | 10.4 | 1.8 | 0.57 | 79.3 [2.1, 241.3] | 1.8 [0.0, 8.5] | 107 | 105 |

| 17 | 100 / 0 / 0 / 0 | 24 hours | Full exclusion compliance + food handling restriction, FE‐3 replaces FE‐1 during 24 hours | 7.7 | 1.1 | 0.33 | 58.5 [1.5, 181.9] | 1.0 [0.0, 5.0] | 79 | 60 |

| 18 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | 100% wear gloves, 100% change gloves, 100% wash hands while changing gloves and in restrooms | 5.7 | 0.7 | 0.17 | 42.6 [0.0, 160.0] | 0.6 [0.0, 3.1] | 58 | 31 |

| 19 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Handwashing efficacy (additional 1log10 reduction) | 6.1 | 0.8 | 0.25 | 45.9 [0.7, 152.0] | 0.8 [0.0, 3.9] | 62 | 46 |

| 20 | 74 / 6.0 / 7.0 / 13 | 24 hours | Handwashing efficacy (additional 2log10 reduction) | 5.2 | 0.7 | 0.20 | 38.9 [0.3, 133.3] | 0.7 [0.0, 3.3] | 53 | 37 |

| 21 | 80 / 0 / 0 / 20 | 24 hours | Baseline + considering only compliant and noncompliant type 3 (did not declare illness and worked while symptomatic) | 10.1 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 77.3 [2.1, 246.9] | 1.8 [0.0, 8.7] | 104 | 111 |

| 22 | 80 / 0 / 0 / 20 | 48 hours | Baseline + considering only compliant and noncompliant type 3 (did not declare illness and worked while symptomatic) + 48 hours | 9.7 | 1.7 | 0.56 | 73.9 [1.7, 243.4] | 1.7 [0.0, 8.3] | 100 | 100 |

Pc: Proportion of compliant food employees regarding the Food Code exclusion recommendation; PNC ;1: proportion of noncompliant food employee type 1, PNC 2: proportion of noncompliant food employee type 1, PNC 3: proportion of noncompliant food employee type 1 (see text and Fig. 2 for further details). FE‐1: food employee 1 (see text and Fig. 2 for further details). The 90% variability interval represents the 5th and the 95th percentiles of the distribution of the number of infected and sick customers over 1,000,000 stores.

Figure 3.

Transmission of norovirus in the retail environment for three scenarios: (A) baseline, (B) scenario 13: no contact with the faucet and the door handle in the restrooms, and (C) scenario 18: no barehand contact, 100% compliance with changing gloves and handwashing while changing gloves according to the FDA Food Code. Food employee 1 is sick and considered noncompliant 2 regarding exclusion period, food employee 2 and food employee 3 are nonshedders. Thickness and gray level of arrows and objects represent the mean value of 1,000 iterations of norovirus transmitted over five shifts.

In the baseline scenario, including an exclusion period of 24 hours after symptom resolution and a compliance rate PC of 74%, the expected proportion of contaminated servings (>0 GEC NoV) is 9.7% and the proportion of highly contaminated servings (> 1,000 GEC NoV) is 0.5%, leading to an expected number of infected and sick customers of 74 and 1.7, respectively, over a total number of 2,000 servings. In this scenario, as is true for all scenarios, a high variability in the number of contaminated servings and in the number of resulting infections and illnesses is observed from store to store, as a function of the specific set of parameters characterizing this store. As an example, the 5th, the median, and the 95th percentiles of the numbers of infected customers estimated from the 1,000,000 simulated stores are 2.1, 48, and 233.7, respectively, in the baseline. This variability reflects notably the variability in the characteristics of the sick food employee (illness duration, shedding level, compliance with exclusion period).

In the lower baseline (scenario 2), in which no food employee is sick but 15% are asymptomatic shedders, the proportion of contaminated servings was evaluated at 1.3%, the proportion of highly contaminated servings at 0.04%, and the mean number of infections and illness at 9.6 and 0.1, respectively. In the upper baseline (scenario 3), where all ill FE‐1 did not declare illness and worked while ill (“noncompliant 3”), the mean number of infected customers increased by 226% compared to the baseline scenario.

The three prevention strategies leading to the smallest numbers of infected customers included either full compliance with handwashing and glove use and no barehand contact (scenario 18, estimated as 58% of infected customers relative to the baseline) or increased handwashing efficiency (additional 1 or 2 log10 reduction during handwashing, scenarios 19 (62%) and 20 (53%), respectively).

Fig. 3 illustrates the norovirus transmission in the retail environment over five shifts for scenario 1 (baseline), scenario 13 (no contact between hands, faucet, and door in restrooms), and scenario 18 (full compliance with handwashing in restrooms, full compliance with handwashing, and wearing and changing gloves when engaging in food preparation), when FE‐1 is sick and from category “non compliant 2,” with FE‐2 and FE‐3 nonill and nonshedders. The main route of contamination is the direct contact with hands in the restrooms (during defecation and vomiting) of the ill food employee (FE‐1), with high levels of norovirus removed during handwashing (>6 log10 over five shifts) in the three scenarios. Fig. 3(a) shows a high level of norovirus transmission to FE‐2 hands (>5 log10 over five shifts) and to FE‐3 hands (>4 log10 over five shifts), while this food employee is not in contact with FCS and foods. Figs. 3(b) and 3(c) show that the level of transmission to food servings and nonill employees is reduced with prevention strategies.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Limitations of the Model/Data

Federal agencies have recommended a number of prevention strategies for mitigating the risk of foodborne illness from norovirus in the retail setting. Even though these prevention strategies are each science based,14 it is difficult not only to measure their relative and combined impacts, but also the relative impact of their level of compliance on public health. Large‐scale experiments would be the gold standard to obtain a better understanding of these impacts, but issues linked to ethics, feasibility, and costs limit the possibility of obtaining data through such experiments. Risk assessment models are a useful alternative in these situations and can inform risk managers on which prevention strategies can best reduce the considered risk of foodborne illness.36

Building a model for all these settings was out of the scope of this article. The situation modeled here is typical of what can be observed and, even though the absolute estimate of the risk may vary in different settings, the relative impact of various preventions and the conclusions of this study are expected to be generalizable. Presymptomatic shedding of the food employees,37 transmission of norovirus between food employees, presence of infected and/or ill customers contaminating the environment, emesis in the kitchen or in the dining room, and presence of contaminated incoming products38, 39, 40 were not included in this study. These features could certainly be included in this discrete event framework.

In risk assessment models, limitations rely on included data and assumptions. The main assumptions of the model are presented in Table VI in three categories: assumptions related to employee practices/behavior and retail setting; assumptions related to illness and norovirus; and assumptions related to data and statistical analysis. It is important to ensure that model results are driven by robust literature data. Our model is based on an extensive literature review and meta‐analyses regarding the survival, disinfection, and transfer of norovirus, hand hygiene, and food employee behavioral practices, including compliance with prevention strategies such as no barehand contact with RTE food. Although many efforts were made during the last decade to conduct observational studies of food employee behavior,20, 25, 26, 41 some practices are not always observable and were assumed in this model such as the number of contacts between food, hands, FCS, and NFCS during food preparation.

Table VI.

Major Assumptions of the Model

| Assumptions Related to Employee Practices/Behavior and Retail Setting |

| The food establishment includes one food preparation area and one restroom |

| Three workers are present in the food establishment, and two of these workers are food workers |

| Five shifts of eight hours were simulated, with 200 servings per food worker and per shift (total of 2,000 servings) |

| The food serving includes three ingredients, one of the ingredients is cooked |

| Food preparation and assembly tasks take place in five‐minute sequences |

| Contact between food, hands/gloves, and FCS occurs twice for each ingredient during food preparation and assembly |

| Contact between hands/gloves and NFCS occurs once for each ingredient during food preparation and assembly |

| The pace of sandwich assembly is 1 per minute |

| The pace of ingredient preparation is 20 pieces per minute |

| Restroom had two hand‐touch points: the hand sink faucet handle and the restroom door handle. |

| Settings studied in the literature used for the meta‐analyses are representative or comparable to this setting |

| Category “noncompliant 3” represents 50% of the proportion of total noncompliant |

| Assumptions Related to Illness and Norovirus |

| Ingredients are initially free of norovirus |

| Restroom, food facility, and food contact equipment are initially free of norovirus |

| Transmission of norovirus to customer only occurs through food |

| Only one employee (FE‐1) is symptomatic |

| Symptomatic employees always experience diarrhea |

| All assumptions from Teunis et al.32 dose–response models (infection and illness) |

| Assumptions Related to Data and Statistical Analysis |

| RT‐PCR data represent the number of norovirus particles in the dose–response model |

| All actions on norovirus particles (transfer, survival, washing, and disinfection) are applied independently on each particle |

| Norovirus surrogates have similar properties (up to a scaling factor) as norovirus (survival, transfer, handwashing, and disinfection) |

| Norovirus genogroup GI and GII have similar properties and infection probability |

The number of infected consumers was used as the major output of our risk assessment model. Teunis et al.’s32 dose–response model leads to a high probability of infection for a low dose that plateaus when a high dose of norovirus is ingested. Indeed, according to this model, the probability of being infected following the ingestion of exactly one norovirus is 0.42; it is 0.67 following the ingestion of 106 norovirus for an Se+ individual, for a 50% human infectious dose (HID50) of 18 norovirus. This dose–response relationship leads to almost direct proportionality between the estimated number of infected individuals and the prevalence of contaminated products (>0 GEC NoV). In contrast, according to these authors, the probability of illness once infected is low if infected with a low dose, and increases with the ingested dose. The probability of symptomatic illness once infected following the ingestion of one norovirus is 9.2 × 10−5; it is 0.33 following the ingestion of 106 norovirus. We took into account preexisting immunity of negative secretors (nonsusceptible population due to a lack of soluble blood group antigens that are believed to interact with the virus)34 but did not include immunity associated with prior episodes of norovirus infection or the fact that genetic susceptibility factors of different norovirus strains may differ from what has already been described for the prototype virus.32, 42 Actually, the accuracy and applicability of this dose–response model is still debated.42, 43, 44, 45 Atmar et al.43 suggested that the 50% human infectious dose for norovirus could be higher, i.e., 2,800 GEC NoV for Se+ individuals. We propose the prevalence of servings with more than 100 and more than 1,000 GEC NoV as an alternative output to the number of infected or sick consumers.

4.2. Discussion of the Results

4.2.1. Routes of Contamination

The contamination of hands in the restrooms, directly from the source or from objects, is the major route of norovirus transmission to the retail environment (Fig. 3). Removing hand contact in the restrooms through the installation of touchless faucets and doors (scenario 13) is much more efficient in reducing the mean number of infected customers (75% compared to the baseline) than increasing the frequency of cleaning restrooms (scenario 10, 97% compared to the baseline).

In contrast to earlier studies,18, 19 emesis in the restroom in addition to diarrhea was incorporated in our model. Vomiting has been recognized to contribute significantly to norovirus transmission, especially in confined environments such as food establishment settings.46, 47 Our analysis found that norovirus particle transfer to objects through aerosolization is much less important than direct hand contact (Fig. 3). This is because a very small number of norovirus particles are transferred through the aerosol to surfaces that the food employees touch.

4.2.2. Impact of Exclusion

Our results confirm the importance of removing symptomatic employees from food establishments as recommended by Hall et al.48 For example, the model estimates a 226% increase in the number of infected customers when ill food employees are not excluded (scenario 3) and a decrease to 75% compared to the baseline with full compliance with the exclusion period (scenario 4).

The importance of removing ill food employees from work can be further illustrated by the mean number of infected customers according to the category of ill food employee present in the store. In fact, if an ill employee was compliant with the exclusion period, or “noncompliant 1,” and hence did not work while ill (as explained in Fig. 2), the mean number of infected customers was estimated to 56 or 60 in the baseline scenario, respectively. However, for the categories “noncompliant 2” and “noncompliant 3,” who worked while ill, the mean number of infected customers was estimated to 109 and 164, respectively. The high levels of infected customers when food employees worked while ill are explained by the high level of norovirus introduced in the retail environment by the ill food employee (FE‐1) due to frequent visits to the restrooms to vomit or defecate. Those visits to the restrooms lead to hand contamination of the ill employee (FE‐1) who then directly contaminate their gloves, the FCS, the NFCS, and the food, or indirectly contaminate the hands of the other food employees, as shown in Fig. 3(a). The impact of a symptomatic food employee in contaminating RTE food items is so strong that other prevention strategies cannot prevent the norovirus contamination of RTE food if a symptomatic food employee is in the food establishment (Figs. 3(b) and 3(c)).

An increase of the exclusion period from 24 to 48 hours after symptom resolution leads to a relatively small decrease in estimated numbers of infected customers when compared with other prevention strategies explored in this risk assessment. This is true whether food employees are fully compliant with the exclusion requirement (8% reduction, scenarios 4 and 5) or not (8% reduction, baseline and scenario 6, or 4% reduction, scenarios 21 and 22). The small decrease in estimated numbers of infected customers when extending the exclusion period to 48 hours primarily arises via the decrease in the level of norovirus in feces during these additional 24 hours away from work, and results from recent human volunteer challenge studies suggest that this decrease is slow.9 Moreover, norovirus shedding continues long after symptoms have resolved.11 The larger impact of the exclusion period extension predicted for the 24 hours (baseline)/48 hours (scenario 6) pair compared with that for the 24 hours (scenario 21)/48 hours (scenario 22) pair arises from preventing some food employees who would have had active symptoms (returned to work too soon before symptom resolution) in the food establishment from working while ill (shift of food employees from NC‐2 to NC‐1 category). In other words, requiring food employees to stay away from work an extra 24 hours could reduce the impact of food employees prematurely declaring the end of symptoms and this is reflected in the overall 8% reduction predicted for scenario 6 as compared with the baseline. The impact of extending the exclusion period depends on the distribution of food employees working while ill among categories NC‐2 and NC‐3.

If implementation of an extended exclusion period to 48 hours after symptom resolution leads to a reduction in compliance with the exclusion, the reduction of norovirus transmission associated with the extended exclusion period shown in scenario 6 could be completely eliminated (scenario 7) or could even lead to an increase in infections and illnesses (scenario 8), depending on the magnitude of the reduction in compliance and the distribution of food employees working while ill among categories NC‐2 and NC‐3. More data are needed to quantify the impact of an extended exclusion period on food employee compliance. Previous studies suggested that as many as 60% of food employees have worked while ill and 20% while experiencing diarrhea or vomiting.25, 26 Many of the influential factors cited by food employees leading to working while ill, such as loss of pay,49 (lack) of severity of illness, and not wanting to leave co‐workers short staffed,25, 50 may become even more important when the period of exclusion is extended.

The model results indicate that a decrease in infected customers comparable to that achieved by extending the exclusion period from 24 to 48 hours could be achieved if compliance with the current 24‐hour exclusion period is increased (compare scenario 6 and 9).

4.2.3. Impact of Restriction

Restricting food employees from preparing food after being ill seems to be counterproductive (scenarios 14 and 16) in our setting. Norovirus transfers from the restricted food employee FE‐1 to hands and gloves of the other food employees FE‐2 and FE‐3 via contamination of the restroom environment and via contact with NFCS (compare scenarios 1 and 14). This result is highly sensitive to the level of interaction between the restricted food employee and the food preparation environment (our results, not shown). We modeled one contact between the hand of the restricted food employee and one NFCS every 10 minutes on average in our model. The increased risk of transmission from a restricted employee was observed because those restricted employees do not wear gloves and wash their hands much less frequently than if they were engaged in food preparation, thereby transferring more norovirus in the setting than they would while preparing food.

4.2.4. Impact of Handwashing, Glove Use, and No Barehand Contact

Our results suggest that handwashing and sanitation (scenarios 19 and 20), no barehand contact with RTE food via glove use in addition to handwashing (scenario 18), and no contact in the restrooms between faucet, door handle, and hands (scenario 13) are highly effective in reducing the transmission of norovirus compared to the baseline. However, glove wearing alone (scenario 11) with current compliance with changing gloves and handwashing when engaging in food preparation does not have a clear impact on decreasing the risk of norovirus transmission. Interestingly, our results suggest that this scenario would increase to 114% the mean number of infected customers, while reducing to 91% compared to the baseline the number of heavily contaminated products (>1,000 GEC NoV). Note that, in our model, we consider norovirus transfer from hands to gloves while the food employee is putting on gloves, as observed in Casanova et al.51 and Ronnqvist et al.52 This unexpected outcome may be explained by the higher norovirus transfer coefficients from gloves to surface and food items than from barehands (see meta‐analysis results in Table I), as shown previously for bacteria.53 This supports that wearing gloves without compliance with handwashing and changing gloves when engaging in food preparation is not enough to reduce the transmission of norovirus in retail settings and highlights the necessity to change gloves and wash hands as recommended in the FDA Food Code. Indeed, scenario 18 shows that it is highly efficient if the food employees regularly change their gloves and wash their hands when they engage in preparation and, importantly, wash their hands in the restrooms.

Interestingly, an increase in the efficiency of handwashing appears to be very successful in reducing the risk linked to norovirus transmission in the retail food service setting (scenarios 19 and 20). A typical handwashing procedure usually removes 1–2 logs of norovirus from the hands.54, 55, 56 Improving this efficiency, through better training, improved handwashing efficacy (such as through the use of soap that increases the level of friction on the hands, without damaging the skin), or other means would reduce the risk of norovirus transmission and foodborne illness in food establishments.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This risk assessment provides a better understanding of the norovirus transmission pathway from infected food employees to RTE food in food establishments and supports the importance of removing symptomatic food employees to prevent norovirus foodborne illnesses. Infected food employees who return to work too soon before full symptom resolution may continue to spread the virus and contaminate food. The effectiveness of exclusion as a preventive control depends on the level of compliance, which, in turn, depends on the reasons and motivations of why food employees may work while ill. This study evaluated the impact of extending the exclusion period after symptom resolution from 24 to 48 hours and found that (1) reduction in mean numbers of infected customers is relatively small when compared with the other prevention strategies; (2) a comparable reduction could be achieved by increasing compliance with the 24‐hour exclusion period; and (3) if compliance with the exclusion requirement is reduced as a consequence of the extension of the postsymptomatic exclusion period, the public health benefit could be reduced, eliminated, or lead to an increase in the mean number of infected customers. Whether or not a public health benefit results from the extension of the postsymptomatic exclusion period and the magnitude of that benefit/harm depend on food employee behavior and more specifically on the level of compliance with the exclusion provision and, among those not complying, the extent to which the change results in these food employees being excluded longer from the food establishment.

This risk assessment identified major areas of improvement to prevent norovirus transmission in these settings, including (1) avoiding the presence of any symptomatic food employees; (2) avoiding the transfer of norovirus from feces or vomit to the hands of food employees by using touchless faucets and eliminating hand contact with the door in restrooms; and (3) avoiding the transfer of norovirus from the hands of food employees to food through proper hand hygiene and the prevention of barehand contact with RTE food. Results of the impact of all preventive strategies on controlling norovirus foodborne illness are largely in line with what was expected in these settings such as the large impact of compliance with exclusion from work while ill, handwashing, or glove use when engaging in food preparation. This research has demonstrated that when evaluating the impact of preventive controls, level of compliance with each preventive strategy should be evaluated separately. More research is needed to identify factors influencing compliance with existing prevention strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study used the computational resources of the HPC clusters at the Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). We would like to thank Glenda Lewis, Dr. Sherri Dennis, Dr. Michael Kulka, Dr. Karl Klontz, Dr. Nega Beru, and Dr. Mickey Parish for their thoughtful reviews of this article. This work was also supported by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hall AJ, Wikswo ME, Pringle K, Gould LH, Parashar UD. Vital signs: Foodborne norovirus outbreaks — United States, 2009–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2014; 63(22):491–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahmed SM, Hall AJ, Robinson AE, Verhoef L, Premkumar P, Parashar UD, Koopmans M, Lopman BA. Global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2014; 14(8):725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lopman BA, Steele D, Kirkwood CD, Parashar UD. The vast and varied global burden of norovirus: Prospects for prevention and control. PLoS Medicine, 2016; 13(4):e1001999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel MM, Hall AJ, Vinje J, Parashar UD. Noroviruses: A comprehensive review. Journal of Clinical Virology, 2009; 44(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hall JA, Ben AL, Daniel CP, Manish MP, Paul AG, Jan V, Umesh DP. Norovirus disease in the United States. Emerging Infectious Disease, 2013; 19(8):1198–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hall JA, Mary EW, Karunya M, Virginia AR, Jonathan SY, Gould LH. Acute gastroenteritis surveillance through the national outbreak reporting system, United States. Emerging Infectious Disease, 2013; 19(8):1305–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. FAO/WHO (World Health Organization) . Viruses in food: Scientific advice to support risk management activities. Microbiological risk assessment series, no. 13, 2008. Available at: http://apps.Who.Int/bookorders/anglais/detart1.Jsp?Sesslan=1&codlan=1&codcol=15&codcch=751.

- 8. CDC (Center of Disease Control) . Norovirus symptoms, 2013. Available at: http://www.Cdc.Gov/norovirus/about/symptoms.Html, Accessed on May 13, 2016.

- 9. Atmar RL, Antone RO, Mark AG, Mary KE, Sue EC, Frederick HN, David YG. Norwalk virus shedding after experimental human infection. Emerging Infectious Disease, 2008; 14(10):1553–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kirby AE, Streby A, Moe CL. Vomiting as a symptom and transmission risk in norovirus illness: Evidence from human challenge studies. PLoS One, 2016; 11(4):e0143759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pringle K, Lopman B, Vega E, Vinje J, Parashar UD, Hall AJ. Noroviruses: Epidemiology, immunity and prospects for prevention. Future Microbiology, 2015; 10(1):53–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zelner JL, Lopman BA, Hall AJ, Ballesteros S, Grenfell BT. Linking time‐varying symptomatology and intensity of infectiousness to patterns of norovirus transmission. PLoS One, 2013; 8(7):e68413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. NACMCF (National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods) . Response to the questions posed by the Food Safety and Inspection Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the Defense Health Agency, Veterinary Services Activity regarding control strategies for reducing foodborne norovirus infections. Journal of Food Protection, 2016; 79(5):843–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) . FDA Food Code 2013 20134/22/2016.

- 15. FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) . Retail Food Protection: Employee Health and Personal Hygiene Handbook, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pouillot R, Gallagher D, Tang J, Hoelzer K, Kause J, Dennis SB. Listeria monocytogenes in retail delicatessens: An interagency risk assessment‐model and baseline results. Journal of Food Protection, 2015; 78(1):134–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berry TD, Mitteer DR, Fournier AK. Examining hand‐washing rates and durations in public restrooms: A study of gender differences via personal, environmental, and behavioral determinants. Environment and Behavior, 2014; 47:923–944. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mokhtari A, Jaykus L‐A. Quantitative exposure model for the transmission of norovirus in retail food preparation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2009; 133(1–2):38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stals A, Jacxsens L, Baert L, Van Coillie E, Uyttendaele M. A quantitative exposure model simulating human norovirus transmission during preparation of deli sandwiches. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2015; 196:126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Green L, Selman C, Banerjee A, Marcus R, Medus C, Angulo FJ, Radke V, Buchanan S. Food service workers’ self‐reported food preparation practices: An EHS‐Net study. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2005; 208(1–2):27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. CDC (Center of Disease Control) . Food safety practices of restaurant workers. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/ehsnet/plain_language/food-safety-practices-restaurant-workers.htm, Accessed on April 26, 2016.

- 22. CDC (Center of Disease Control) . Food worker handwashing and food preparation. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/ehsnet/plain_language/food-worker-handwashing-food-preparation.htm, Accessed on April 12, 2016.

- 23. Phillips G, Tam CC, Rodrigues LC, Lopman B. Prevalence and characteristics of asymptomatic norovirus infection in the community in England. Epidemiology Infection, 2010; 138(10):1454–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arias C, Sala MR, Dominguez A, Torner N, Ruiz L, Martinez A, Bartolome R, de Simon M, Buesa J. Epidemiological and clinical features of norovirus gastroenteritis in outbreaks: A population‐based study. Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2010; 16(1):39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carpenter LR, Green AL, Norton DM, Frick R, Tobin‐D'Angelo M, Reimann DW, Blade H, Nicholas DC, Egan JS, Everstine K, Brown LG, Le B. Food worker experiences with and beliefs about working while ill. Journal of Food Protection, 2013; 76(12):2146–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sumner S, Brown LG, Frick R, Stone C, Carpenter LR, Bushnell L, Nicholas D, Mack J, Blade H, Tobin‐D'Angelo M, Everstine K. Factors associated with food workers working while experiencing vomiting or diarrhea. Journal of Food Protection, 2011; 74(2):215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barker J, Jones MV. The potential spread of infection caused by aerosol contamination of surfaces after flushing a domestic toilet. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2005; 99(2):339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tung‐Thompson G, Libera DA, Koch KL, de Los Reyes FL, , 3rd Jaykus LA . Aerosolization of a human norovirus surrogate, bacteriophage ms2, during simulated vomiting. PLoS One, 2015; 10(8):e0134277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. Pp. 267–281 in 2nd International Symposium on Information Theory: Akadémiai Kiado, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vose D. Risk Analysis: A Quantitative Guide, 3rd ed Chichester, UK: Wiley and Sons, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jaloustre S, Guillier L, Morelli E, Noël V, Delignette‐Muller ML. Modeling of clostridium perfringens vegetative cell inactivation in beef‐in‐sauce products: A meta‐analysis using mixed linear models. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2012; 154(1–2):44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]