Abstract

Background and aim

Evaluations of alcohol policy changes demonstrate that restriction of trading hours of both ‘on’‐ and ‘off’‐licence venues can be an effective means of reducing rates of alcohol‐related harm. Despite this, the effects of different trading hour policy options over time, accounting for different contexts and demographic characteristics, and the common co‐occurrence of other harm reduction strategies in trading hour policy initiatives, are difficult to estimate. The aim of this study was to use dynamic simulation modelling to compare estimated impacts over time of a range of trading hour policy options on various indicators of acute alcohol‐related harm.

Methods

An agent‐based model of alcohol consumption in New South Wales, Australia was developed using existing research evidence, analysis of available data and a structured approach to incorporating expert opinion. Five policy scenarios were simulated, including restrictions to trading hours of on‐licence venues and extensions to trading hours of bottle shops. The impact of the scenarios on four measures of alcohol‐related harm were considered: total acute harms, alcohol‐related violence, emergency department (ED) presentations and hospitalizations.

Results

Simulation of a 3 a.m. (rather than 5 a.m.) closing time resulted in an estimated 12.3 ± 2.4% reduction in total acute alcohol‐related harms, a 7.9 ± 0.8% reduction in violence, an 11.9 ± 2.1% reduction in ED presentations and a 9.5 ± 1.8% reduction in hospitalizations. Further reductions were achieved simulating a 1 a.m. closing time, including a 17.5 ± 1.1% reduction in alcohol‐related violence. Simulated extensions to bottle shop trading hours resulted in increases in rates of all four measures of harm, although most of the effects came from increasing operating hours from 10 p.m. to 11 p.m.

Conclusions

An agent‐based simulation model suggests that restricting trading hours of licensed venues reduces rates of alcohol‐related harm and extending trading hours of bottle shops increases rates of alcohol‐related harm. The model can estimate the effects of a range of policy options.

Keywords: Agent‐based modelling, alcohol‐related harm, dynamic simulation modelling, evaluation, simulation, trading hour policy

Introduction

Preventing alcohol misuse and its harms is a complex, systemic problem 1, 2. Harms associated with alcohol consumption are estimated to account for 5.9 % of all deaths and 5.1 % of the burden of disease globally, with costs amounting to more than 1 % of gross national product in high‐income countries 3, 4. Policies regulating alcohol availability including temporal restrictions (reductions in trading hours) are a suggested key strategy for reducing alcohol‐related harms and are reported to be second only to pricing policy in terms of their effectiveness 5. A number of reviews have highlighted the effectiveness of policies that restrict trading hours on reducing alcohol‐related harms 6, 7, 8. A more recent systematic review has added further strength to this evidence, pointing to well‐designed intervention studies from Australia, Norway and the Netherlands that have demonstrated impacts (of restricting on‐licensed venue trading hours) of 16 to 37 % reduction in alcohol‐related harms 5. Previous studies have also examined the impact of reduced trading hours of bottle shops (off‐license), demonstrating significant reductions in hospitalisations in teenagers and young adults 9, 10. However, studies examining the effect of temporal restrictions on bottle shop trading hours have been less closely considered than on‐license venue trading hour restrictions 5.

Despite this evidence base, policy makers face significant challenges as they attempt to set effective but acceptable policies that enhance public safety while avoiding significant policy resistance. Alcohol is a prominent commodity in the Australian market place with various groups promoting its association with positive aspects of life, and is subject to community resistance to regulation of its availability and use 11, 12. There also remain uncertainties regarding the effect of restrictions or relaxation of trading hours on both on‐ and off‐ license venues in different contexts, and changing population characteristics over time. In addition, there are challenges with identifying the independent effects of trading hour changes from other commonly coupled interventions including regulation of outlet density, responsible service of alcohol, and use of ‘lock‐out’ policies 13 (that is, the restriction of movement of patrons between venues after a specified time).

Computer simulation models are valuable tools for conducting virtual policy experiments before solutions are implemented in the real world 14, 15. They provide a low‐risk way of testing assumptions, managing uncertainty, and better understanding the quantitative trade‐offs of different policy options to support decision making and knowledge translation 16. They can be used to conduct experiments not possible in the real world with the aim of identifying the most acceptable and effective policy responses in particular contexts, and importantly, provide a mechanism for estimating the impacts, both beneficial and adverse, of a policy option into the future 17. Agent‐based models (ABMs) are a class of computational model that provide powerful tools for simulating human behaviour due to their ability to capture the interacting influences of individual characteristics, social networks, local context, and the broader economic and policy environment 18 that are important drivers of alcohol behaviours and risk of harms. ABMs are underpinned by complexity theory, with their architecture drawing on both theory and empirical data as they attempt to create a virtual representation of real world systems in order to better understand the nature and consequences of human behaviour.’ In practical terms, agents (individuals) in the model are given key characteristics and exposures that reflect those in the real world. Based on these characteristics and changes in exposures over time, conditional transition rules are articulated (based on best available evidence, theory, and expert knowledge) that specify how simulated individuals act and interact in different circumstances. Resulting population‐level behavioural patterns and outcomes emerge from millions of stochastic interactions. The model is then tested and validated against real‐world historic data patterns across a range of outcome indicators. The primary advantage of dynamic modelling (such as agent‐based modelling) is their ability to forecast quantifiable impacts and assess the effects of different policy or intervention (‘what if’) scenarios into the future, taking into consideration different contexts, changing exposures over time, and the effects of other interventions.

Participatory approaches to the development of such models and their use are recommended to ensure transparency and accountability for model parameters, estimates, assumptions, data sources and model outputs 19, 20. Participatory model development also serves to engage stakeholders and potential end‐users – improving communication and garnering broader support for collaborative action based on model outputs 21, 22, 23, 24, 25. While models of alcohol consumption behaviour have been developed 26, 27, 28, 29, a participatory approach to the application of agent‐based simulation modelling to estimate the impact over time of different trading hour policies has not been previously reported. Therefore, a participatory simulation modelling study was undertaken to explore the impacts on acute alcohol‐related harms of different trading hour policy options for on‐ and off‐ license venues.

Method

Model design and development

An agent‐based model of alcohol consumption behaviour was developed to explore the impact of different licensed venue trading hour policy scenarios on acute harms over time 30. The model structure, parameterisation and the participatory approach used and its development are described in detail elsewhere 19, 30. Briefly, model development was undertaken using a participatory stakeholder engagement and consensus building approach. Stakeholders involved were academics, policy experts, clinicians, health service providers, program planners and health economists 19. The model was designed to simulate 3.6 million individuals and was calibrated to approximate population statistics of the state of New South Wales, Australia from 2011 to 2016 and then to project output estimates from January 1st 2017 to December 31st 2021 when simulating the baseline and intervention scenarios.

Model inputs and structure

At model initialisation, the distribution of demographic characteristics (age and sex), weight (in kilograms) and alcohol consumption (classified as low, moderate, or heavy) of ‘agents’ (individuals) reflected the empirical distribution of these factors in the NSW population for 2011. ‘Low’ alcohol consumption was defined as ≤2 standard drinks per day, ‘moderate’ was defined as 3–6 standard drinks per day, and ‘heavy’ defined as ≥7 standard drinks per day 31, 32. The model captured the interdependence between a range of risk factors (including age, sex, access, density, pricing, habit, self‐regulation, and peer pressure), population and behavioural dynamics, social network influences and variations in intervention impacts over time.

The structure and parameterisation of the model drew on a range of evidence and data sources (see Appendix S1 for summary and Atkinson et al. 2017 30 for full parameter list and data sources) including systematic reviews (and meta‐analyses), longitudinal studies, well‐accepted formulas and conceptual models, and local survey data. Model structure and parametrisation was reviewed and modified in response to the combined expert knowledge of participating stakeholders through a series of model co‐design workshops to reach consensus. In addition, demographic data were sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, drinking behaviour data sourced from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NSW & Australian data), incidence of harm data was sourced from the Australian Burden of Disease Study dataset. Emergency department (ED) presentation and hospitalisation data were sourced from NSW Health administrative datasets. These data were used for model initialisation, calibration and validation purposes.

Model outputs

Key acute alcohol harm outcome indicators simulated and compared to the baseline were: (i) incidence of acute alcohol‐related harms, (ii) incidence of alcohol‐related violence, (iii) ED presentations, and (iv) hospitalisations. To account for stochasticity, each simulation was run 12 times. A description of the output data processing method is presented in Appendix S2. Outcomes of the simulated scenarios are provided in Table 1 and are presented as a mean per 100 000 population across the 12 runs. In addition, comparison of simulation results between baseline and intervention scenarios are expressed as a percent difference in the mean of two independent samples for the same population. Where relevant, differential impacts of scenarios on the key outcome indicators for males, females and between drinking categories are reported. The key assumptions of the model and supporting citations are provided in Appendix 3. The agent‐based model was constructed using AnyLogic simulation software (http://www.anylogic.com/).

Table 1.

Summary statistics for each scenario including % reduction from the baseline.a

| Mean monthly harms generated (per 100 000 population)b | % reduction from baseline | Margin of error % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence of acute harms | |||

| Scenario 1 ‐ Early closing of licensed venues at 3 a.m. | 39.0 | 12.3 | ± 2.4 |

| Scenario 2 ‐ Early closing of licensed venues at 1 a.m. | 35.4 | 20.5 | ± 2.7 |

| Scenario 3 ‐ Extending bottle shop trading hours to 11 a.m. | 47.3 | −6.3 | ± 2.9 |

| Scenario 4 ‐ Extending bottle shop trading hours to 12 a.m. | 47.5 | −6.6 | ± 3.2 |

| Scenario 5 ‐ Extending bottle shop trading hours to 2 a.m. | 48.4 | −8.8 | ± 2.7 |

| ED presentations | |||

| Scenario 1 ‐ Early closing of licensed venues at 3 a.m. | 25.3 | 11.9 | ± 2.1 |

| Scenario 2 ‐ Early closing of licensed venues at 1 a.m. | 23.6 | 19.4 | ± 2.3 |

| Scenario 3 ‐ Extending bottle shop trading hours to 11 a.m. | 30.3 | −5.6 | ± 2.7 |

| Scenario 4 ‐ Extending bottle shop trading hours to 12 a.m. | 30.4 | −5.9 | ± 2.6 |

| Scenario 5 ‐ Extending bottle shop trading hours to 2 a.m. | 31.2 | −8.5 | ± 2.3 |

| Hospitalizations | |||

| Scenario 1 ‐ Early closing of licensed venues at 3 a.m. | 21.0 | 9.5 | ± 1.8 |

| Scenario 2 ‐ Early closing of licensed venues at 1 a.m. | 19.3 | 16.9 | ± 2.0 |

| Scenario 3 ‐ Extending bottle shop trading hours to 11 a.m. | 24.0 | −3.3 | ± 2.1 |

| Scenario 4 ‐ Extending bottle shop trading hours to 12 a.m. | 24.0 | −3.4 | ± 2.0 |

| Scenario 5 ‐ Extending bottle shop trading hours to 2 a.m. | 24.2 | −4.5 | ± 1.9 |

All results are calculated for a 95 % confidence interval.

These values are based on a simulated population of approximately 3.6 million. Mean monthly statistics for alcohol‐related violence cannot be obtained reliably due to rare events and therefore not reported in the table. However, % reduction across the 5‐year period is provided in the text. ED = emergency department.

Simulation experiments

Simulation experiments were conducted that addressed a key alcohol policy issue that is the subject of debate in the state of New South Wales, Australia and internationally: the extension or reduction of closing times of licensed venues 33, 34. The baseline (business as usual) case simulated outcomes across a 5‐year period from January 2017 to December 2021 and assumed no changes to existing conditions across NSW; that is, varying densities of licensed venues across NSW, a state‐wide bottle shop closing time of 10 pm, and on‐license venue closing time up to 5 am. The following intervention scenarios were simulated and compared against the baseline:

-

Scenario 1.

Early closing of on‐licensed venues at 3 am across NSW in 2017.

-

Scenario 2.

Early closing of on‐licensed venues at 1 am across NSW in 2017.

-

Scenario 3.

Extending bottle shop (off‐license) trading hours to 11 pm across NSW in 2017.

-

Scenario 4:

Extending bottle shop (off‐license) trading hours to 12 am across NSW in 2017.

-

Scenario 5:

Extending bottle shop (off‐license) trading hours to 2 am across NSW in 2017.

Results

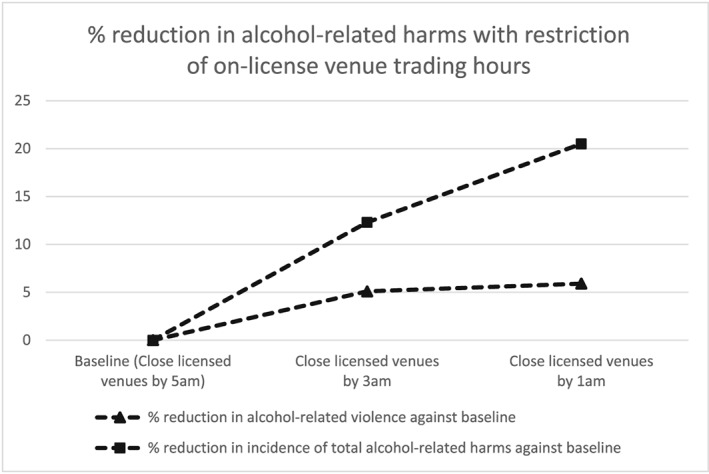

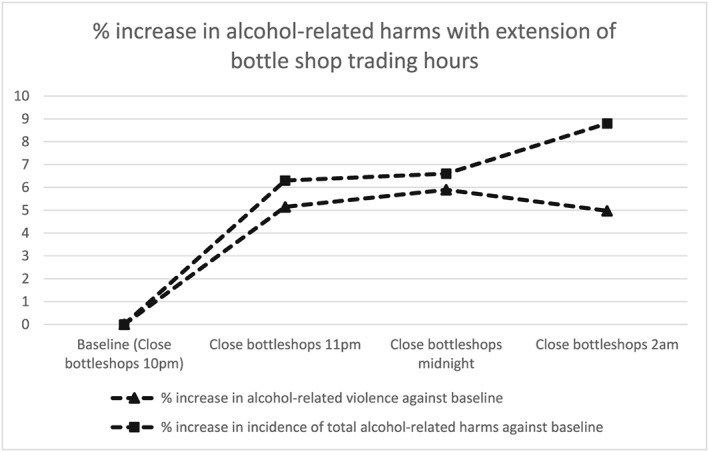

The impact of all scenarios on key outcome indicators for the period 2017 to 2021 are presented in Table 1, Figs. 1 and 2, and described below.

Figure 1.

Impact of early closing of on‐licence venues

Figure 2.

Impact of extending bottle shop closing times

Scenario 1

The modelled effects of the implementation of 3 am closing time for on‐license venues that trade beyond this time across NSW from 2017 are presented in Table 1. This scenario produced significant reductions in acute harms, ED presentations and hospitalisation, as well as a 7.9 ± 0.8 % reduction in alcohol‐related violence between 2017 and the end of 2021. Compared to the baseline, this scenario produced the greatest reduction in the incidence of acute harms among female heavy drinkers (19.3 ± 4.9 %), compared to a 15.2 ± 3.4 % reduction in harms among male heavy drinkers.

Scenario 2

The modelled effects of the implementation of 1 am closing time for on‐license venues that trade beyond this time across NSW in 2017 are presented in Table 1. This scenario produced substantial reductions in acute harms, ED presentations and hospitalisations, as well as a 17.5 ± 1.1 % reduction in alcohol‐related violence between 2017 and the end of 2021. Compared to the baseline, this scenario produced the greatest reductions in the incidence of acute harms occurred among heavy drinkers (females, 25.3 ± 4.5 %; males, 24.7 ± 3.7 %). However, a substantial reduction was also seen among females consuming alcohol at moderate levels (a 23.7 ± 6.5 %). Figure 1 suggests a linear relationship between earlier on‐license venue closing times and reduction in alcohol‐related violence.

Scenario 3

The modelled effects of an extension of bottle shop (off‐license) closing times to 11 pm across NSW in 2017 are presented in Table 1. This scenario resulted in an increase in harms across the full range of indicators, including a 5.1 ± 0.8 % increase in alcohol‐related violence between 2017 and the end of 2021. Compared to the baseline, this scenario produced the greatest impact for females consuming alcohol at heavy and moderate levels (10.7 ± 7.0 % and 8.2 ± 6.2 % increase in the incidence of acute alcohol‐related harms respectively) and males consuming alcohol at moderate levels (a 10.4 ± 6.7 % increase in acute harms).

Scenario 4

The modelled effects of an extension of bottle shop (off‐license) closing times to 12 am across NSW in 2017 are presented in Table 1. This scenario resulted in an increase in harms across the full range of indicators, including a 5.9 ± 1.1 % increase in alcohol‐related violence between 2017 and the end of 2021. Compared to the baseline, this scenario produced the greatest impact on the incidence of acute alcohol‐related harms occurred among females consuming alcohol at heavy levels (a 12.4 ± 7.0 % increase in harms) and males consuming alcohol at moderate levels (11.7 ± 8.9 % increase).

Scenario 5

The modelled effects of an extension of bottle shop (off‐license) closing times to 2 am across NSW in 2017 are presented in Table 1. This scenario resulted in an increase in harms across the full range of indicators, including a 5.0 ± 0.9 % between 2017 and the end of 2021. Compared to the baseline, this scenario produced the greatest impact occurred among females consuming alcohol at heavy levels (a 13.9 ± 5.6 % increase in harms) and males consuming alcohol at moderate levels (13.5 ± 9.9 % increase). Fig. 2 suggests a non‐linear increase in alcohol‐related violence with extension of bottle shop (off‐license) opening hours.

Discussion

This simulation study explored the impact of various trading hour policy scenarios on four acute alcohol‐related harms in the state of New South Wales, Australia, testing the effect of temporal changes to licensed venue and bottle shop distributors of alcohol. While the direction of findings was consistent with that of the existing literature in demonstrating higher rates of harm with increasing trading hours and reduced harms with restriction of trading hours, the effects sizes are overall more conservative than what has been demonstrated in previous studies of trading hour interventions in New South Wales. This difference may be explained in part by the real‐world environment including further relevant factors not included in the simulation. However, it may also be due to the model assessing the impact of temporal changes in closing hours implemented at scale across the state of NSW, whereas in actual policy changes to date, licensed venue closing hour changes (and their estimated impacts) have focussed on localised, highly dense entertainment precincts and have been coupled with other policy measures 35, 36.

The results of this study differ from an earlier review of 14 natural experiments carried out by Hahn et al. (2010) who concluded that changes to opening hours of licensed venues are unlikely to affect alcohol consumption and related harms unless the change in opening times is greater than two hours in a day 6. Our findings are more consistent with recent empirical studies in Australia and elsewhere that demonstrate marked impacts from relatively small changes to permissible hours 5. In particular, alongside the evidence from Newcastle 35 and Sydney 36, Rossow and Norstrom 37 identified significant impacts on harm rates in 18 Norwegian cities for changes to trading hours of just one or two hours.

The size of the impact of changes to trading hours is highly context specific with particular outlet types and particular types of harm varying substantially between studies 5, 38. The time it takes to trial and evaluate alternative policy options, and the potential political costs in trialling ineffective or unpopular policy scenarios, mean that contextually‐relevant agent‐based simulation models provide a valuable tool for testing alternative licensed venue trading hour policy scenarios and understanding quantitatively their trade‐offs, before they are implemented in the real world. Given the consistency in the direction of the findings with national and international studies despite differences in analytic method, the current simulation study further strengthens the key role of license venue training hours as a driver of acute alcohol related harms. Such findings suggest that policy makers need to address the strong likelihood of increases in harms when considering policies that increase the trading hours of licensed venues. This is particularly the case given the finding of a linear relationship between trading hours and alcohol related violence for on‐license premises.

Findings suggest that there are likely to be increases in a range of harms with the extension of bottle shop closing hours from 10 pm to 11 pm. This is an area with limited empirical evidence, and findings have important policy implications given the recent extension of bottle shop trading hours to 11 pm in New South Wales 39. There have been few evaluations of policy‐changes relating to packaged liquor trading hours, although the two existing studies 9, 10 demonstrate significant impacts on harms among young people, suggesting the model results are at least broadly plausible. Monitoring and evaluation of the impact of the recent policy change will therefore be important. Findings also suggest that compared to the baseline, changes to trading hour policies in NSW are likely to have the greatest impact on the incidence of alcohol‐related harms among females consuming alcohol at heavy levels. This finding is in part explained by lower baseline rates of acute harms in female compared to male heavy drinkers (mean monthly acute harms of 11.7 and 19.7 per 100 000 population respectively), thereby producing greater proportional impacts in harms from changes to absolute number of cases as a result of the simulated policy scenario. In addition, as suggested by a review of evidence from Nordic countries, the greatest impacts of policies occur among those whose behaviour is most restricted by the policy 40; in this case, heavy drinkers. Evidence for gender‐specific effects of policies are inconsistent, divergent and dependent on context and culture, with differential effects possibly explained by factors not evenly distributed among men and women 40. In the NSW alcohol model, such factors include gender differences in social expectations around drinking in particular contexts, peer pressure related to an individual's social network, employment sectors, and weight distributions (used in the calculation of blood alcohol concentration).

Limitations

The model does not include domestic violence as a measure of alcohol harm, hence model outputs relating to violence and total acute harms will be an underestimate of the impact of trading hour policies on alcohol‐related harms. In addition, for reasons of simplicity, the model does not incorporate immigration or migration in the state of NSW. This results in a total population reduction over time (~0.45 % per year). In addition, population‐level evidence was often used to parameterise individual‐level transitions in the agent based model due to a lack of more detailed individual‐level data regarding the impact of interacting exposures on drinking behaviours. Further collection of individual behavioural trajectory data (e.g. using sensor‐enabled wearable devices and mobile technologies) would make a valuable contribution to improving model robustness, particularly with regards to improving model representation of the interactions between workplace drinking culture, gender‐related social expectations around drinking in particular contexts, and peer pressure related to an individual's social network. However, the primary purpose of the model was to provide decision support capability by estimating the overall comparative impacts of different policy scenarios over time against the baseline rather than providing highly precise estimates of outcome indicators. A strength of the study, and a key innovation in the application of simulation models to public health settings, is the explicit engagement of key stakeholders in the design and development of the simulation modelling tool 16, 19, 20, 21. The participatory approach assisted with transparent negotiation and consensus building around the most acceptable policy options in the context of previous, and sometimes contentious, empirical evidence. This approach has developed an effective and acceptable cross‐sectoral policy analysis tool to inform responses to reducing alcohol‐related harms.

In conclusion, the simulations demonstrated that the late‐night trading hours of licensed venues and bottle shops are a key determinant of the rates of alcohol‐related harms. The results demonstrate that dynamic simulation models provide a valuable additional tool for testing the possible impacts of alternative licensed venue and bottle shop trading hour policy scenarios over time, before they are implemented in the real world.

Declaration of interests

None.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Summary of types of literature and data used and the role of expert stakeholders in model development.

Appendix S2 Data processing method.

Appendix S3 Model assumptions and supporting citations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Alcohol Modelling Consortium 30 who participated in the development of the model. This research was supported by the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre through the NHMRC partnership centre grant scheme (Grant ID: GNT9100001) with the Australian Government Department of Health, NSW Ministry of Health, ACT Health, HCF and the HCF Research Foundation. The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the individual authors and do not reflect the views of the NHMRC or funding partners.

Atkinson, J.‐A. , Prodan, A. , Livingston, M. , Knowles, D. , O'Donnell, E. , Room, R. , Indig, D. , Page, A. , McDonnell, G. , and Wiggers, J. (2018) Impacts of licensed premises trading hour policies on alcohol‐related harms. Addiction, 113: 1244–1251. doi: 10.1111/add.14178.

References

- 1. Babor T., Caetano R., Casswell S., Edwards G., Giesbrecht N., Graham K. et al Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity. Research and Public Policy, 2nd edn. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marlatt G. A., Witkiewitz K. Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: health promotion, prevention, and treatment. Addict Behav 2002; 27: 867–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO) . Global status report on alcohol and health. Luxembourg: WHO; 2014. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112736/1/9789240692763_eng.pdf (accessed 31 August 2017) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6xNn6qPXj on 21 February 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rehm J., Mathers C., Popova S., Thavorncharoensap M., Teerawattananon Y., Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol‐use disorders. Lancet 2009; 373: 2223–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilkinson C., Livingston M., Room R. Impacts of changes to trading hours of liquor licences on alcohol‐related harm: a systematic review 2005–2015. Public Health Res Pract. 2016; 26: e2641644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hahn R. A., Kuzara J. L., Elder R., Brewer R., Chattopadhyay S., Fielding J. et al Effectiveness of policies restricting hours of alcohol sales in preventing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med 2010; 39: 590–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Popova S., Giesbrecht N., Bekmuradov D., Patra J. Hours and days of sale and density of alcohol outlets: impacts on alcohol consumption and damage: a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol 2009; 44: 500–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stockwell T., Chikritzhs T. Do relaxed trading hours for bars and clubs mean more relaxed drinking? A review of international research on the impacts of changes to permitted hours of drinking. Crime Prevention Community Saf 2009; 11: 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marcus J., Siiedler T. Reducing binge drinking? The effect of a ban on late‐night off‐premise alcohol sales on alcohol‐related hospital stays in Germany. J Public Econ 2015; 123: 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wicki M., Gmel G. Hospital admission rates for alcoholic intoxication after policy changes in the canton of Geneva. Switzerland. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011; 118: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diepeveen S., Ling T., Suhrcke M., Roland M., Marteau T. M. Public acceptability of government intervention to change health‐related behaviours: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tindall J., Groombridge D., Wiggers J., Gillham K., Palmer D., Clinton‐McHarg T., et al Alcohol‐related crime in city entertainment precincts: Public perception and experience of alcohol‐related crime and support for strategies to reduce such crime. Drug Alcohol Rev 2016; 35: 263–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Donnelly N., Poynton S., Weatherburn D. The effect of the lockout and last drinks laws on non‐domestic assaults in Sydney: an update to September 2016. Crime and Justice Bulletin No. 201. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Homer J., Hirsch G. System dynamics modeling for public health: background and opportunities. Am J Public Health 2006; 96: 452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Atkinson J., Page A., Wells R., Milat A., Wilson A. A modelling tool for policy analysis to support the design of efficient and effective policy responses for complex public health problems. Implement Sci 2015; 10: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freebairn L., Atkinson J., Kelly P., McDonnell G., Rychetnik L. Simulation modelling as a tool for knowledge mobilisation in health policy settings: a case study protocol. Health Res Policy Syst 2016; 14: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Milstein B., Jones A., Homer J. B., Murphy D., Essien J., Seville D. Charting plausible futures for diabetes prevalence in the United States: a role for system dynamics simulation modeling. Prev Chronic Dis 2007; 4: A52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marshall B. D., Galea S. Formalizing the role of agent‐based modeling in causal inference and epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2015; 181: 92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Atkinson J., O'Donnell E., Wiggers J., McDonnell G., Mitchell J., Freebairn L. et al Dynamic simulation modelling of policy responses to reduce alcohol‐related harms: rationale and procedure for a participatory approach. Public Health Res Pract 2017; 27: 2711707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O'Donnell E., Atkinson J. A., Freebairn L., Rychetnik L. Participatory simulation modelling to inform public health policy and practice: rethinking the evidence hierarchies. J Public Health Policy 2017; 38: 203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Atkinson J., Wells R., Page A., Dominello A., Haines M., Wilson A. Applications of system dynamics modelling to support health policy. Public Health Res Pract. 2015; 25: e2531531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loyo H. K., Batcher C., Wile K., Huang P., Orenstein D., Milstein B. From model to action: using a system dynamics model of chronic disease risks to align community action. Health Promot Pract 2013; 14: 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rouwette E. A. J. A., Vennix J. A. M., van Mullekom T. Group model building effectiveness: a review of assessment studies. Syst Dyn Rev 2002; 18: 5–45. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Royston G., Ayesha D., Townshend J., Turner H. Using system dynamics to help develop and implement policies and programmes in health care in England. Syst Dyn Rev 1999; 15: 293–313. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Freebairn L., Rychetnik L., Atkinson J., Kelly P., McDonnell G., Roberts N. et al Knowledge mobilisation for policy development: implementing systems approaches through participatory dynamic simulation modelling. Health Res Policy Syst 2017; 15: 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fitzpatrick B., Martinez J. Agent‐based modeling of ecological niche theory and assortative drinking. J Artif Soc Soc Simul 2012; 15: 4. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gorman D. M., Mezic J., Mezic I., Gruenewald P. J. Agent‐based modeling of drinking behavior: a preliminary model and potential applications to theory and practice. Am J Public Health 2006; 96: 2055–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lamy F., Perez P., Ritter A., Livingston M. An agent‐based model of alcohol use and abuse: SimARC In: Muller J. F., Bousquet F., editors. Proceedings of the 7th European Social Simulation Association (ESSA) Conference. Montpellier: ESSA; 2011, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scott N., Livingston M., Hart A., Wilson J., Moore D., Dietze P. SimDrink: an agent‐based NetLogo model of young, heavy drinkers for conducting alcohol policy experiments. J Artif Soc Soc Simulation 2016; 19: 10. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Atkinson J., Knowles D., Prodan A., Livingston M., O'Donnell E., Room R. et al Harnessing advances in computer simulation to inform policy and planning to reduce alcohol‐related harms. J Int Public Health 2017; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-1041-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) . Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks From Drinking Alcohol. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government, NHMRC; 2009. Available at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/ds10-alcohol.pdf (accessed 31 August 2017) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6xNnQJEyp on 21 February 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marsden Jacob Associates . Bingeing, Collateral Damage and the Benefits and Costs of Taxing Alcohol Rationally: Report to the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education. Melbourne, Australia: Marsden Jacob Associates; 2012. Available at: http://bettertax.gov.au/files/2015/06/Foundation_for_Alcohol_Research_and_Education_Submission_2.pdf (accessed 31 August 2017) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6xNnaTR03 on 21 February 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 33. Manton E., Room R., Livingston M. Limits on trading hours, particularly latenight trading In: Manton E., Room R., Giorgi C., Thorn M., editors. Stemming the Tide of Alcohol: Liquor Licensing and the Public Interest. Canberra: Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education; 2014, pp. 122–136. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miller P. G., Ferris J., Coomber K., Zahnow R., Carah N., Jiang H. et al Queensland Alcohol‐related Violence and Night Time Economy Monitoring project (QUANTEM): a study protocol. BMC Public Health 2017; 17: 789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kypri K., McElduff P., Miller P. Restrictions in pub closing times and lockouts in Newcastle, Australia five years on. Drug Alcohol Rev 2014; 33: 323–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Menendez P., Kypri K., Weatherburn D. The effect of liquor licensing restrictions on assault: a quasi‐experimental study in Sydney, Australia. Addiction 2017; 112: 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rossow I., Norstrom T. The impact of small changes in bar closing hours on violence. The Norwegian experience from 18 cities. Addiction 2012; 107: 530–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gmel G., Holmes J., Studer J. Are alcohol outlet densities strongly associated with alcohol‐related outcomes? A critical review of recent evidence. Drug Alcohol Rev 2015; 25: 40–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brook B. NSW Government to allow bottle shops to open until 11pm. 2016. Available at: http://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/food/drink/nsw-government-to-allow-bottle-shops-to-open-until-11pm/news-story/c78050447f232eaab13095ec414a0473 (accessed 31 August 2017) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6xNnjvXAL on 21 February 2018).

- 40. Mäkelä P., Rossow I., Tryggvesson K. Who drinks more and less when policies change? In: Room R., editor. The Effects of Nordic Alcohol Policies: What Happens to Drinking when Alcohol Controls Change? NAD Publication 42. Helsinki: Nordic Council for Alcohol and Drug Research; 2002, pp. 17–70. Available at: http://www.drugslibrary.stir.ac.uk/documents/nad42.pdf (accessed 31 August 2017) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6xNnsGXMD on 21 February 2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Summary of types of literature and data used and the role of expert stakeholders in model development.

Appendix S2 Data processing method.

Appendix S3 Model assumptions and supporting citations.