Need for Rapid Feedback of Data for Quality Assurance and Improvement

In order to improve delivery of cancer care, monitoring of the quality of care is needed and information collected in clinical cancer registries is an ideal basis for this purpose 1, 2. However, until recently there have been substantial delays in reporting from these registries but to be useful as a metric for quality improvement such data need to be rapidly collected, collated, and reported in an actionable and user‐friendly format soon after the event of interest has occurred 3. These reports should then be part of local quality assurance systems for optimal effect 4. In addition, publicly available, user‐friendly versions of these reports can provide further incentive to improve quality of care, but to date register data have rarely been presented in such a way.

Here we describe a public, interactive online reporting system based on data collected in the National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden, a clinical prostate cancer register. The online report is posted in April in the year following the year of diagnosis.

Creation of an Online Reporting System

The NPCR captures data for 98% of all men diagnosed with prostate cancer in Sweden since 1998 and held data on 181 660 incident prostate cancer cases in March 2018 5. For staff directly involved in patient care, real‐time data are available at a password‐secured server but until recently, public reporting from the NPCR merely consisted of an annual pdf report 3. In order to improve data access, the NPCR created an open online interactive reporting system in Swedish and English (http://www.npcr.se/RATTEN) by use of the module SHINY in the ‘R’ software package. This report is available in April following the most recent calendar year of diagnosis included in the report.

Data from the NPCR in the Reporting System

At the start page of the reporting system (http://www.npcr.se/RATTEN) a short description of the report is provided and some key data are presented, e.g. number of new cases diagnosed during the previous year. There are six tabs in the reporting system with a total of 53 variables in the areas of capture (n = 2), diagnostic evaluation (n = 6), primary treatment (n = 20), and waiting times (n = 6). Users select the source population (all, one, or several out of six healthcare regions), year(s) of diagnosis, patient age and prostate cancer risk category, and level of aggregation (nation, region, county, or hospital). In this way, a ‘tailor made’ report for the selected variable is created by use of the requested source population for the defined subgroup of patients at the selected level of aggregation. The report is presented as a figure, heat map, or table (which can readily be exported as a spreadsheet). Ten variables have been selected as quality indicators for urological care and nine indicators for oncological care, and are included under specific tabs. These indicators were selected from the Swedish National Prostate Cancer Guidelines in consensus with the NPCR steering group 3. The quality indicators for urology consists of the proportion of men: (i) who were reported to the NPCR within 30 days of cancer diagnosis; (ii) who had a named clinical nurse specialist; (iii) had a first outpatient visit within 14 days after referral; (iv) who were informed of their cancer diagnosis within 11 days after prostate biopsy; (v) below the age of 80 years with high‐risk cancer who were investigated with bone imaging; (vi) below the age of 75 years with very‐low‐risk cancer who started active surveillance (AS); (vii) with high‐risk cancer for whom curative treatment could be considered who were discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting; (viii) below the age of 75 years with localised high‐risk cancer who received curative treatment; (ix) with low‐ or intermediate‐risk cancer in whom nerve‐sparing was performed at prostatectomy; and (x) with pT2 cancer at prostatectomy who had negative margins.

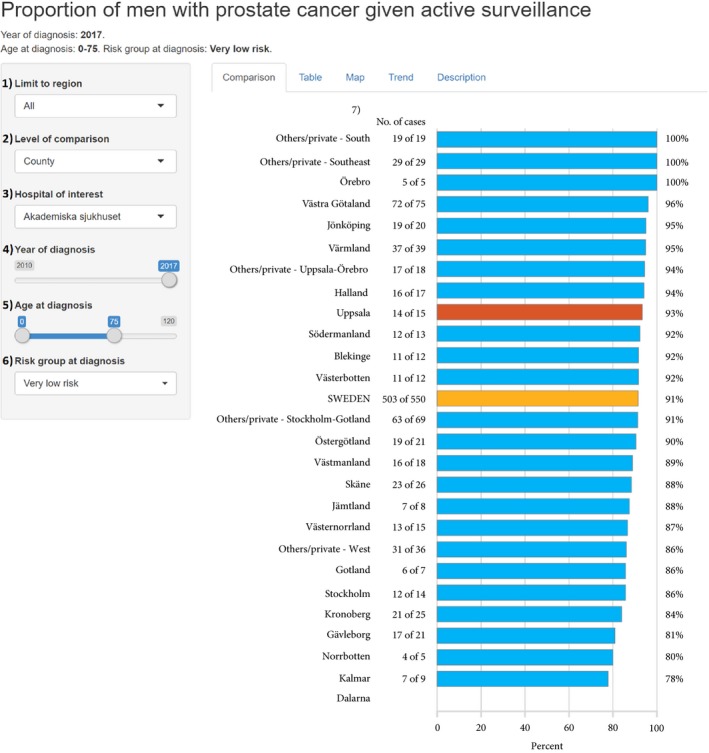

Assessment of a large number of aspects of prostate cancer care can rapidly be obtained from the reporting system. For example, the choice of primary treatment strategy at all Swedish hospitals for men with very‐low‐risk prostate cancer in 2017 is shown in Fig. 1 6.

Figure 1.

Use of AS, as a primary treatment strategy, for men in Sweden up to the age of 75 years diagnosed with very‐low‐risk prostate cancer in 2017 per county reported in the online interactive reporting system at http://www.npcr.se/RATTEN. At http://www.npcr.se/RATTEN the user can select: (1) source population; all or any of the six health care region(s); (2) level of comparison: hospital, county, or health care region; (3) unit of interest, here marked in red; (4) the year(s) of diagnosis; (5) age range of the source population; (6) risk category; (7) denotes the column with the number of men who received AS out of all men in this risk group. Data are not displayed for counties with fewer than five cases. Data from each private healthcare provider are shown only when one single healthcare region is used as the source population. Very‐low‐risk prostate cancer was defined as clinical stage T1c, Gleason Grade Group 1, PSA level of <10 ng/mL, PSA density <0.15 ng/mL, <8 mm total cancer length in ≤4 positive biopsy cores 6. Figure based on data on men diagnosed in 2017 reported up to 8 March 2018. In 2016, for which there is complete capture, exactly the same percentage of men up to the age of 75 years with very‐low‐risk cancer started AS (619/681; 91%).

Implementation and Preliminary Results

There have been changes in the pattern of prostate cancer care in Sweden that we tentatively attribute to previous reporting from the NPCR. For example, there has been a strong increase in the use of AS in men with low‐risk prostate cancer in parallel with the open annual reporting from the NPCR on this issue to all departments in Sweden 6. To what extent this new open reporting system will provide additional incentive for improvement remains to be seen. It is encouraging that 6 months after the launch of this reporting system, it is used by the Swedish Prostate Cancer Association, a patient interest group, to retrieve information on the quality of prostate cancer care by all healthcare providers. In addition, data are also used in dialogue with healthcare organisations and decision‐makers to improve prostate cancer care, e.g. by displaying adherence to guidelines for appropriate evaluation and treatment, as well as reporting of waiting times.

In conclusion, public online reporting systems from clinical cancer registers provide a means of transparent reporting that hold promise to become an additional incentive for improvement of cancer care.

Funding Source

This project was supported by funds to the NPCR from the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Stacy Loeb is supported by a Young Investigator Award from the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the Blank Family Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K07CA178258.

Conflict of Interest

Stacy Loeb has received honoraria for lectures from Astellas, consulting fees from Lilly, GE and GenomeDx, and reimbursed travel to a conference from Astellas and Sanofi. The other authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Abbreviations

- AS

active surveillance

- NPCR

National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by the continuous work of the NPCR steering group: Pär Stattin (Chairman), Anders Widmark, Camilla Thellenberg Karlsson, Ove Andrén, Ann‐Sofi Fransson, Magnus Törnblom, Stefan Carlsson, Marie Hjälm‐Eriksson, David Robinson, Mats Andén, Jonas Hugosson, Ingela Franck Lissbrant, Maria Nyberg, Ola Bratt, Calle Waller, Olof Akre, Per Fransson, Eva Johansson, Fredrik Sandin, Karin Hellström.

References

- 1. Verne J, Hounsome L, Kockelbergh R, Rashbass J. Improving outcomes from prostate cancer: unlocking the treasure trove of information in cancer registries. Eur Urol 2016; 69: 1013–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hiatt RA, Tai CG, Blayney DW et al. Leveraging state cancer registries to measure and improve the quality of cancer care: a potential strategy for California and beyond. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015; 107: djv047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stattin P, Sandin F, Sandback T et al. Dashboard report on performance on select quality indicators to cancer care providers. Scand J Urol 2016; 50: 21–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGlynn EA, Adams JL, Kerr EA. The quest to improve quality: measurement is necessary but not sufficient. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 1790–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, Wigertz A et al. Cohort profile update: the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden and Prostate Cancer data Base – a refined prostate cancer trajectory. Int J Epidemiol 2016; 45: 73–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Curnyn C, Robinson D, Bratt O, Stattin P. Uptake of active surveillance for very‐low‐risk prostate cancer in Sweden. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3: 1393–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]