Abstract

Background

Consumption of oily fish or fish oil during pregnancy, lactation and infancy has been linked to a reduction in the development of allergic diseases in childhood.

Methods

In an observational study, Icelandic children (n = 1304) were prospectively followed from birth to 2.5 years with detailed questionnaires administered at birth and at 1 and 2 years of age, including questions about fish oil supplementation. Children with suspected food allergy were invited for physical examinations, allergic sensitization tests, and a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled food challenge if the allergy testing or clinical history indicated food allergy. The study investigated the development of sensitization to food and confirmed food allergy according to age and frequency of postnatal fish oil supplementation using proportional hazards modelling.

Results

The incidence of diagnosed food sensitization was significantly lower in children who received regular fish oil supplementation (relative risk: 0.51, 95% confidence interval: 0.32‐0.82). The incidence of challenge‐confirmed food allergy was also reduced, although not statistically significant (0.57, 0.30‐1.12). Children who began to receive fish oil in their first half year of life were significantly more protected than those who began later (P = .045 for sensitization, P = .018 for allergy). Indicators of allergy severity decreased with increased fish oil consumption (P = .013). Adjusting for parent education and allergic family history did not change the results.

Conclusion

Postnatal fish oil consumption is associated with decreased food sensitization and food allergies in infants and may provide an intervention strategy for allergy prevention.

Keywords: allergy prevention, EuroPrevall, fish oil, food allergy, infants

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- DBPCFC

double‐blind, placebo‐controlled food challenge

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- IgE

immunoglobulin E

- LUH

Landspitali University Hospital

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- RR

relative risk

- SPT

skin prick test

- Th1

T helper cell 1

1. INTRODUCTION

Dietary changes have been suggested as an important factor for increasing prevalence of food allergy. Of special interest is the declining intake of omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n‐3 PUFA) with the concurrent rise in omega‐6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n‐6 PUFA) and vitamin D deficiency.1, 2 n‐3 PUFA have an anti‐inflammatory effect by influencing the cell membrane structure, cell signalling and antigen presentation.3, 4 Diets rich in the n‐3 PUFA eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) have been shown to decrease allergic symptoms in food‐allergic mice. DHA‐rich diet also protected against allergic sensitization, indicating both primary and secondary prevention.5

Several studies have indicated a favourable allergic outcome in infants related to maternal n‐3 PUFA consumption during pregnancy, although there have been inconsistent results between studies.6

The Childhood Asthma Prevention Study in Australia showed that infants who received fish oil supplementation from birth had increased n‐3 PUFA levels in association with a decreased allergen‐specific T helper cell 2 (Th2) response and elevated polyclonal Th1 response, indicating that n‐3 PUFA have immunomodulatory effects during a critical time of immune vulnerability in early infant life.7 The improved infant n‐3 PUFA status did not prevent childhood allergic disease.8, 9

Low vitamin D status has been reported in concordance with an increase in allergic diseases in infancy. Vitamin D modulates the action of immune cells, such as T and B cells, monocytes and dendritic cells, and may, therefore, influence the development of allergic diseases, including food allergy.10, 11 Studies have shown conflicting results regarding the association between vitamin D and the development of food allergy, but recent studies have suggested a rather protective role.1, 12, 13

To examine whether cod fish oil supplementation, which is rich in n‐3 PUFA and vitamins A and D, has an effect on food allergy development, we evaluated the Icelandic birth cohort taking part in the EuroPrevall birth cohort study on food allergies using a questionnaire database as well as information on sensitization and confirmed food allergy. Results published so far from the EuroPrevall birth cohort show that, compared with the other participating European countries, Iceland is relatively high in food allergy prevalence.14, 15, 16

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

This study is a longitudinal observational study without intervention. The Icelandic directorate of health recommends that infants be given vitamin D, 10 μg daily, from age 2 weeks until 6 months when it is recommended to begin supplementing daily 5 mL dose of fish oil. However, many parents in our cohort were not compliant with these recommendations, which provided an opportunity to investigate the relationship between vitamin D and fish oil supplementation and food allergy in Icelandic infants.

The analysis was performed using data collected from the EuroPrevall birth cohort study in Iceland conducted within the collaborative research initiative EuroPrevall. The methodology of the birth cohort has previously been described in detail.17 Participation was offered to parents of children born in Iceland from 2005 to mid‐2008. Participating children were followed from birth to 2.5 years of age. Data for 1341 children were collected after birth and included birth data, family history of allergies in parents and siblings, socio‐demographic status and environmental exposures.

Parents were asked to call to report any symptoms in their children that were suggestive of food allergy. They underwent a standardized interview by a study nurse and, if needed, by a paediatric allergist, and a decision was made regarding whether to bring the child to the Landspitali University Hospital (LUH) in Reykjavik for interviewing and examination. In addition, parents answered questionnaires over the phone at approximately 12 and 24 months. Data were collected on breastfeeding, complementary intake and food intake of the child and symptoms of allergies. When allergy was suspected, a decision was again made on whether to bring the child to the hospital.

The children who were brought to LUH underwent a physical examination, skin prick testing (SPT) and a blood draw for food‐specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) measurements, and when allergy was suspected, a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) was offered. The DBPCFC diagnosis was based on immediate symptoms or delayed symptoms reported by parents within 24 hours (Appendix S1).

2.2. Data and subjects for this study

The participants in this study were the children who completed a 12‐month questionnaire. The primary data used were the questionnaire responses regarding complementary feeding of fish oil and vitamin D during infancy, family history of allergy and demographic factors as well as the results of the hospital allergy examination. In this study, the term regular for both fish oil and vitamin D intake was used to represent administration at least four times per week. Fish oil supplementation is common in Iceland, and it is officially recommended that children should be given fish oil from 6 months of age. The fish oil is primarily from cod and is rich in n‐3 PUFA and vitamins A and D (Table S1). Vitamin D supplementation is recommended from age 2 weeks.18

To allow testing for confounding by family allergy history, a family allergy index was computed, measuring the frequency and severity of allergic diseases in first‐degree relatives (Appendix S2). In addition, to allow for quantitative analysis, a sensitization and allergy severity index for the children was computed by combining the results of the IgE measurements, SPT and DBPCFC (Appendix S3).

2.3. Statistics

Matlab (version 2017a; MathWorks Inc.), including its Statistics toolbox, was used to perform the statistical analyses. For the demographic characteristics in the previous subsection, P‐values for fractions were computed using the chi‐square test, and P‐values for means were computed using one‐way analysis of variance. Fisher's exact test was used for the P‐values in the preliminary calculation subsection below. For detailed analysis, a proportional hazards model was built to estimate the protective effect of giving infants fish oil during their first 2 years, incorporating vitamin D supplementation, the family allergy index and various other potentially confounding factors. The model estimated relative risk (RR); a likelihood ratio was used to compute P‐values; and confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained with profile likelihood. For quantitative analysis of the relationship between fish oil use and allergy severity, a linear regression model of food allergy severity on the frequency of fish oil use was constructed, with the t test used to determine the P‐value (Appendix S4).

2.4. Ethics

The study was approved by The National Bioethics Committee in Iceland (2005; VSNb2005070004) and the Icelandic Data Protection Agency (2005/421). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents prior to the participation of their children in the study.

3. RESULTS

Of the 1341 children for whom birth data were collected, the 12‐month questionnaire was completed for 1304 children, resulting in the participation of 636 girls and 668 boys in this study. The 24‐month questionnaire was completed for 1244 children. A total of 515 parents called and were interviewed by a study nurse and, subsequently, by a study physician, that is paediatric allergist, if food allergy was suspected. A total of 249 children were seen at LUH for further investigation.

3.1. Primary findings

The primary result of the study was that regular fish oil use significantly reduced the incidence of food sensitization (RR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.32‐0.82, P = .006) in Icelandic infants irrespective of their family history of allergy and other investigated confounding factors. Incidence of sensitization and confirmed food allergy were significantly lower in children who began early on regular fish oil (P = .045 and .018, respectively, Table 1).

Table 1.

Food sensitization and food allergy between 9.5 and 30 mo of age in three subgroups according to different fish oil use

| Subgroup | n | Sensitized to ≥1 food allergen (aged 9.5‐30 mo) | Food allergy (aged 9.5‐30 mo) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Begin regular fish oil 3‐6 mo old | 596 | 16 (2.7%) | 5 (0.8%) |

| Begin regular fish oil 7‐9 mo old | 281 | 9 (3.2%) | 4 (1.4%) |

| No regular fish oil before 15 mo | 241 | 13 (5.4%) | 7 (2.9%) |

| P‐value (using logistic regression) | .045 | .018 |

The table shows the cumulative incidence of sensitization among the children who were not sensitized at 9.5 mo according to whether they began regular fish oil when 3‐6 mo old, when 7‐9 mo old or whether they did not receive regular fish oil supplementation before 15 mo. The last column shows the incidence of confirmed food allergy among the same children.

3.2. Demographic factors, fish oil use and vitamin D

Almost half of the study group was given fish oil regularly from the age of 6 months or younger, and a further third began regular fish oil intake at 7‐15 months old. Table 2 summarizes the main demographic characteristics of the 1304 participating children according to the age at which regular fish oil intake began. There were 787 children who were given vitamin D regularly, prior to fish oil use, beginning at 0‐2 months old and 517 who either received it less often or started later. There were three variables that were significantly related to fish oil use: presence of animals at home, administration of infant formula with cow's milk during the first week and fish oil intake during pregnancy. These variables received special attention in the modelling described below, and none of them were found to have a confounding effect on the primary results.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the 1304 Icelandic EuroPrevall birth cohort study participants

| Characteristic | Total | Regular fish oil beginning when 1‐6 mo old | Regular fish oil beginning when 7‐15 mo old | No regular fish oil before 15 mo | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size of group (fraction of total) | 1304 (100.0%) | 599 (45.9%) | 434 (33.3%) | 271 (20.8%) | |

| Girls (fraction of group) | 636 (49%) | 299 (50%) | 201 (46%) | 136 (50%) | .664 |

| No 0‐ to 7‐y‐old siblings at home | 724 (56%) | 343 (57%) | 230 (53%) | 151 (56%) | .602 |

| High parent education | 718 (55%) | 333 (56%) | 238 (55%) | 147 (54%) | .985 |

| Animals at home | 290 (22%) | 154 (26%) | 75 (17%) | 61 (23%) | .016 |

| Regular fish oil during pregnancy | 710 (54%) | 368 (61%) | 219 (50%) | 123 (45%) | <.001 |

| Regular vit. D supplem. starting before 3 mo | 787 (60%) | 372 (62%) | 262 (60%) | 153 (56%) | .478 |

| Infant formula with cow milk during 1st week | 387 (30%) | 199 (33%) | 117 (27%) | 71 (26%) | .082 |

| Daily smoking during pregnancy | 104 (8%) | 48 (8%) | 34 (8%) | 22 (8%) | .999 |

| Family allergy severity index | 2.1 ± 2.0 | 2.1 ± 1.9 | 2.1 ± 2.2 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | .666 |

| Mother's age in years | 30.1 ± 4.8 | 30.0 ± 4.8 | 30.1 ± 4.8 | 30.2 ± 4.8 | .843 |

The last two lines show mean ± standard deviation.

Children with a family history of allergy did not receive significantly more or less fish oil than other children. Of the 635 children with a family allergy index above the median, 297 (47%) began regular fish oil supplementation at 1‐6 months old, and an additional 204 (32%) began supplementation at 7‐15 months old. Of the other 639 children who had a low family allergy index, 304 (48%) began regular fish oil intake at 1‐6 month old and another 244 (38%) began at 7‐15 months old. The family allergy index was also incorporated in the modelling phase and did not alter the results.

3.3. Diagnosed food sensitization and allergy

As stated above, 249 children were seen at LUH after food allergy was suspected. Of these children, 85 (6.5% of the 1304) were diagnosed as sensitized to food based on positive SPT and/or IgE outcomes. For 43 (3.3%) of the 85 children, the diagnosis was confirmed as food allergy with DBPCFC. In 6, 1 and 2 cases, the children were allergic to 2 foods, 3 foods and 4 foods, respectively. The most common food allergens were hen's eggs and cow's milk, followed by fish and peanuts (Table 3).

Table 3.

Positive outcomes of sensitization/food challenge tests in 249 Icelandic EuroPrevall birth cohort children, up to 2.5 y of age

| Number of tests with a positive outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Food | SPT | IgE/RAST | DBPCFC |

| Eggs | 51 | 46 | 28 |

| Milk | 30 | 46 | 13 |

| Peanuts | 14 | 19 | 6 |

| Fish | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| Wheat | 5 | 21 | 2 |

| Soy | 2 | 17 | |

| Hazelnut | 2 | ||

| Almond | 1 | ||

| Cashew | 1 | ||

| Green pea | 2 | ||

| Nutramigen | 1 | ||

| Total | 119 | 158 | 57 |

| Total children | 69 | 71 | 43 |

SPT, skin prick test, DBPCFC: double‐blind placebo‐controlled food challenge. IgE/RAST: serum IgE >0.35 kUA/L.

3.4. Fish oil and food allergy—preliminary calculation

There were 595 children, not allergic at 6 months, who received regular fish oil from that age or earlier. Of these, 24 (4.0%) were subsequently diagnosed with food sensitization and 11 (2.0%) with confirmed food allergy. This contrasts with the 241 children who never received regular fish oil. Of these, 27 (11.2%) were diagnosed with food sensitization and 20 (7.9%) with food allergy after age 6 months (P < .001 for both sensitization and confirmed allergy). Similar computation for vitamin D only, and for vitamin D and fish oil combined, showed marginal but nonsignificant protection of vitamin D (Table S2).

3.5. Modelling the relationship between fish oil use and food allergy

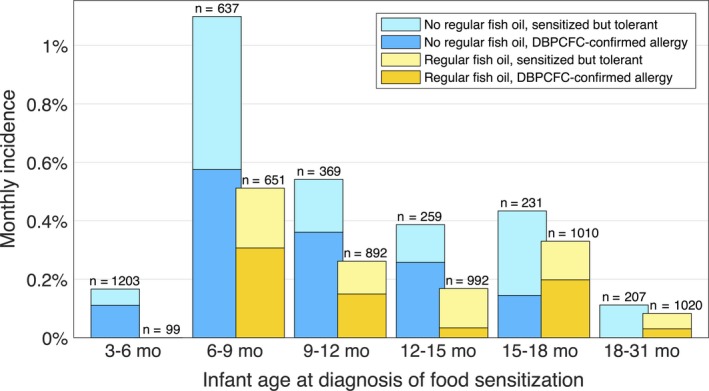

The calculation in the previous subsection did not consider the 464 children who began regular fish oil intake after 6 months of age, but they were included in the more detailed analysis illustrated in Figure 1, which also provides a breakdown by age at diagnosis. The analysis is explained in more detail in Figure S1; however, briefly, the incidence of sensitization (allergy) among those who had begun regular fish oil intake was compared with the incidence among those who had not. For the analysis, the exact timing of the shift, that is from not getting fish oil to getting regular fish oil, was considered to be 2 weeks after the fish oil start time reported by the parents in the questionnaire(s).

Figure 1.

Monthly incidence of food sensitization and allergy according to age and fish oil use. The upper part of each bar (lighter colour) shows the incidence of sensitization, diagnosed during the indicated age span, that is not accompanied by a positive double‐blind placebo‐controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) outcome, and the lower part (darker colour) shows the incidence of sensitization followed by a positive DBPCFC outcome. The numbers above the bars indicate the size of each reference group. On average, regular fish oil intake lowered the incidence of sensitization by a factor of 2.0 (P = .006) and DBPCFC‐confirmed allergy by a factor of 1.7 (nonsignificant, P = .095). See Figure S1 for details

Until age 15 months, the incidence of diagnosed sensitization against food allergens among children who had received regular fish oil was less than half that among the children who had not received regular fish oil, and the same was true for confirmed allergy. After 15 months, the difference in incidence was smaller; however, firm conclusions cannot be drawn because there were only a few cases.

A proportional hazards model was constructed to estimate the protective effect of fish oil in terms of RR. The detailed results are shown in Table S3 (sensitization) and Table S4 (DBPCFC‐allergy). As stated at the beginning of this section, the primary result of the modelling was that regular fish oil use significantly reduced the incidence of food sensitization irrespective of family history of allergy, and also irrespective of sex, mother's age, number of (young) siblings, presence of pets or other animals in the home, smoking in the home, parents’ education, mother's use of fish oil during pregnancy and consumption of complementary cow milk in the first week (Table S3, models 15‐22, Table S4, models 16‐23). The modelling also showed an insignificant reduction in DBPCFC‐confirmed allergy (RR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.30‐1.12, P = .101). Other possible confounding variables, including caesarean birth, breastfeeding and birthweight, were also checked and found to have negligible and insignificant effects (data not shown). Detailed breakdown of sensitization and allergy incidence according to age and fish oil use is shown in Figure S1.

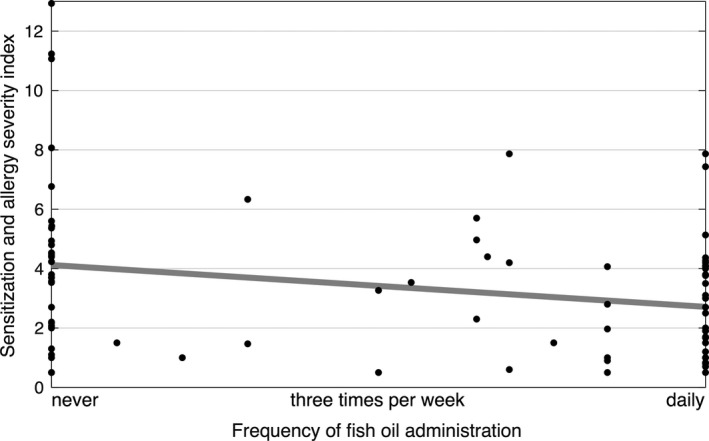

3.6. Fish oil and food allergy severity

To investigate whether there was a quantitative relationship between the amount of fish oil given and allergy severity, a linear regression model was constructed. The results indicated that for children who did receive fish oil and became sensitized/allergic to food, the severity of the condition, measured by the sensitization and allergy severity index, decreased with the amount of fish oil per week (Figure 2). There were multiple questions on the frequency of fish oil supplementation in the questionnaires, and when the responses were inconsistent, an average was used. Models that included family allergy history and other confounding variables yielded similar results (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Sensitization and allergy severity index according to the frequency of fish oil administration. There was a significant relationship (linear regression t test, P = .013)

3.7. Vitamin D supplementation and food sensitization and allergy

Regular vitamin D from an early age, prior to fish oil supplementation, was not found to have a significant independent, protective effect at the P = .05 level, neither on sensitization (RR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.55‐1.34) nor on food allergy (RR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.26‐1.52, Tables S3 and S4).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Findings of this study and other research

The Icelandic EuroPrevall birth cohort gave us a unique opportunity to prospectively explore the fish oil supplementation status in Icelandic children up to 2.5 years of age and relate our results to food sensitization and food allergy. Our study investigated the effect of postnatal supplementation with fish oil and the development of sensitization to food allergens and DBPCFC‐confirmed food allergy. We reported that the incidence of sensitization to food allergens and DBPCFC‐confirmed food allergy up to 2.5 years is halved when supplementing with fish oil in infancy. We also reported a dose‐dependent relationship of allergy severity and consumption of fish oil in the same children. Early vitamin D supplementation (recommended from 2 weeks of age) tended to provide additional protection, although this finding was not statistically significant in our model.

Other human studies of postnatal fish oil supplementation have not shown a similar effect on allergy development. D'Vaz et al,8 in their study in Australia, did not find significant effects of postnatal fish oil intervention on the development of allergic diseases in the first year of life, although it was associated with a favourable effect on immune function at 6 months. They did find a significant reduction in eczema prevalence if participants were more than 75% compliant with the supplementation, indicating that some minimal dose of fish oil is needed. In that study, capsules containing 250‐280 mg of DHA and 100‐110 mg of EPA were used, whereas in our study, each 5‐mL dose of fish oil recommended beginning at age 6 months contained 650 mg of DHA and 350 mg of EPA as well as 9.2 μg of vitamin D, 138 μg of vitamin A, 4.6 mg of vitamin E and 1.8 g of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA; Table S1). The mothers in the Australian study had restricted fish intake in the last trimester, whereas fish intake was not restricted in our study. The additional ingredients in the fish oil may possibly play a role, such as vitamin A, which has been shown to participate in oral tolerance development,19 and MUFA, but blood MUFA have recently been associated with reduced allergy risk at 2‐9 years of age.20

Fish oil supplementation during pregnancy and lactation is known to have an immunomodulatory and allergy‐preventive effect on the offspring.21 In our study, the effect of postnatal fish oil supplementation on sensitization or confirmed food allergy did not change when accounting for the mother's intake of fish oil during pregnancy. Furthermore, the maternal fish oil consumption during pregnancy in our study did not explain the dose‐dependent effect of fish oil intake by the infants on allergy severity.

Another Australian intervention study used, in a double‐blind manner, 500‐mg tuna fish oil capsules containing 184 mg of omega‐3 fatty acids once daily from the age of 6 months vs capsules with sunflower oil. They did not find a significant difference in allergic diseases between the intervention group and the controls up to the age of 3 years apart from reduced atopic cough in the intervention group.7 Again, the total dose of omega‐3 fatty acids in this study was much lower than that in our study (184 mg vs 1000 mg), which could explain the different results between these studies. A high dose of omega‐3 fatty acids during pregnancy has been shown to be more favourable for reducing the development of allergic diseases in infancy than a lower dose.22

Another important factor was the vitamin D content of the Icelandic fish oil. A recent meta‐analysis and systematic review of maternal vitamin D status (umbilical blood or serum) and childhood allergic diseases showed an association between low maternal vitamin D during pregnancy and an increased risk of childhood eczema, but not childhood asthma or wheezing.23 A new study by Hollams et al, also from Australia, investigated atopic development and vitamin D levels from birth to 10 years of age in a high‐risk birth cohort. They demonstrated with repeated vitamin D measurements that vitamin D level was inversely associated with allergic sensitization, asthma and eczema at 10 years. The authors noted that a single measurement of vitamin D used in many negative studies may reflect a short exposure, while repeated measurements reflect ongoing vitamin D exposure and protection.13 The same research group previously demonstrated that low vitamin D at 6 years of age leads to an increased risk of developing allergic sensitization.24

In addition to the dose‐dependent explanation given above for the difference between the two Australian studies7, 8 and this study, exposure to the Australian sun may also play a role, by providing all the Australian participants with adequate vitamin D.

The timing of fish oil supplementation seems to be important, as we demonstrated more protection when starting fish oil early. Animal and human studies have indicated that n‐3 PUFA can change the expression of genes by an epigenetic mechanism and affect the production of inflammatory mediators and the development of allergic diseases.25, 26 There is accumulating evidence that supplementation with fish oil rich in PUFA and vitamin D has an effect on the immune system and may, thereby, prevent the development of allergic diseases and that the critical time to initiate supplementation is very early in life.10, 11, 22, 27, 28, 29

4.2. Limitations and strengths of this study and future challenges

This study is part of a larger observational food allergy birth cohort study, which was not designed to focus on fish oil and vitamin D. It would have been preferable to obtain more frequent information on vitamin D and fish oil supplementation. Another limitation is that we only checked the sensitization of children who reported some symptoms of allergy, but not the whole cohort, which means that there may have been some sensitized, nonsymptomatic children who were not accounted for. Due to a lack of statistical power, we were unfortunately not able to examine possible specific protective effects of fish oil on different types of allergens, as suggested by results from a Dutch experimental study.5

Nevertheless, this was a prospective study based on a large cohort of 1304 normal‐risk children recruited prenatally. Information on a large number of possible confounding factors was collected and used in our modelling, and DBPCFC, the gold standard for the diagnosis of food allergy, was used. Fish oil supplementation for infants and children is a cultural habit in Iceland. At the same time, a considerable number of parents do not follow the official recommendations, providing a unique opportunity to compare two large groups of children, namely, those who receive and do not receive fish oil.

Our results apply to Icelandic children, and it would be interesting to carry out a similar analysis based on the EuroPrevall cohort for other European countries, both within countries and between countries. Further studies are needed to determine which of the ingredients in the cod fish oil explain the protective findings of our study.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our study showed that fish oil supplementation in children starting before or at 6 months may decrease food sensitization and food allergy in young children by more than half, with potential large public health implications. The study also indicated that regular fish oil may decrease food allergy severity.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Michael Clausen performed the data collection, carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and critically reviewed, revised and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Kristjan Jonasson performed the statistical analysis and drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Thomas Keil designed and was the co‐principal investigator for the EuroPrevall birth cohort study, supervised the data collection, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Kirsten Beyer designed and was the principal investigator for the EuroPrevall birth cohort study, supervised the data collection, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Sigurveig T. Sigurdardottir was a local principal investigator for the EuroPrevall birth cohort study in Iceland, conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised the data collection, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the families who participated in the EuroPrevall birth cohort study, the medical and nursing staff in the Pediatric Department of the LUH, especially Anna Gudbjorg Gunnarsdottir, Hlif Sigurdardottir, Gudlaug Gudjonsdottir, Hildur S. Ragnarsdottir and Ingibjorg Halldorsdottir, as well as the prenatal care nurses and midwives at LUH and in primary health care in Iceland. This study was part of the EuroPrevall birth cohort project and was funded by the European Commission (FOOD‐CT‐2005‐514000), Landspitali University Hospital Science Fund and GlaxoSmithKline Iceland.

Clausen M, Jonasson K, Keil T, Beyer K, Sigurdardottir ST. Fish oil in infancy protects against food allergy in Iceland—Results from a birth cohort study. Allergy. 2018;73:1305–1312. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13385

REFERENCES

- 1. Molloy J, Ponsonby AL, Allen KJ, et al. Is low vitamin D status a risk factor for food allergy? Current evidence and future directions. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2015;15:944‐952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simopoulos AP, DiNicolantonio JJ. The importance of a balanced omega‐6 to omega‐3 ratio in the prevention and management of obesity. Open Heart. 2016;3:1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Calder PC. The relationship between the fatty acid composition of immune cells and their function. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;79:101‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Snijdewint FG, Kalinski P, Wierenga EA, Bos JD, Kapsenberg ML. Prostaglandin E2 differentially modulates cytokine secretion profiles of human T helper lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1993;150:5321‐5329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van den Elsen LW, Bol‐Schoenmakers M, van Esch BC, et al. DHA‐rich tuna oil effectively suppresses allergic symptoms in mice allergic to whey or peanut. J Nutr. 2014;144:1970‐1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Best KP, Gold M, Kennedy D, Martin J, Makrides M. Omega‐3 long‐chain PUFA intake during pregnancy and allergic disease outcomes in the offspring: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:128‐143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peat JK, Mihrshahi S, Kemp AS, et al. Three‐year outcomes of dietary fatty acid modification and house dust mite reduction in the Childhood Asthma Prevention Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:807‐813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'Vaz N, Meldrum SJ, Dunstan JA, et al. Postnatal fish oil supplementation in high‐risk infants to prevent allergy: randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2012;130:674‐682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. D'Vaz N, Meldrum SJ, Dunstan JA, et al. Fish oil supplementation in early infancy modulates developing infant immune responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:1206‐1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muehleisen B, Gallo RL. Vitamin D in allergic disease: shedding light on a complex problem. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:324‐329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Suaini NH, Zhang Y, Vuillermin PJ, Allen KJ, Harrison LC. Immune modulation by vitamin D and its relevance to food allergy. Nutrients. 2015;7:6088‐6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allen KJ, Koplin JJ, Ponsonby A‐L, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with challenge‐proven food allergy in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1109‐1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hollams EM, Teo SM, Kusel M, et al. Vitamin D over the first decade and susceptibility to childhood allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:472‐481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McBride D, Keil T, Grabenhenrich L, et al. The EuroPrevall birth cohort study on food allergy: baseline characteristics of 12,000 newborns and their families from nine European countries. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:230‐239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xepapadaki P, Fiocchi A, Grabenhenrich L, et al. Incidence and natural history of hen's egg allergy in the first 2 years of life‐the EuroPrevall birth cohort study. Allergy. 2016;71:350‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schoemaker AA, Sprikkelman AB, Grimshaw KE, et al. Incidence and natural history of challenge‐proven cow's milk allergy in European children–EuroPrevall birth cohort. Allergy. 2015;70:963‐972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keil T, McBride D, Grimshaw K, et al. The multinational birth cohort of EuroPrevall: background, aims and methods. Allergy. 2010;65:482‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Icelandic Directorate of Health . Næring ungbarna (Infant nutrition) 2017. http://www.landlaeknir.is/servlet/file/store93/item32231/naering_ungbarna_loka.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- 19. Turfkruyer M, Rekima A, Macchiaverni P, et al. Oral tolerance is inefficient in neonatal mice due to a physiological vitamin A deficiency. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:479‐491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mikkelsen A, Galli C, Eiben G, et al. Blood fatty acid composition in relation to allergy in children aged 2‐9 years: results from the European IDEFICS study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:39‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klemens CM, Berman DR, Mozurkewich EL. The effect of perinatal omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation on inflammatory markers and allergic diseases: a systematic review. BJOG. 2011;118:916‐925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calder PC. Fishing for allergy prevention. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43:700‐702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wei Z, Zhang J, Yu X. Maternal vitamin D status and childhood asthma, wheeze, and eczema: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:612‐619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hollams EM, Hart PH, Holt BJ, et al. Vitamin D and atopy and asthma phenotypes in children: a longitudinal cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1320‐1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoile SP, Clarke‐Harris R, Huang RC, et al. Supplementation with N‐3 long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids or olive oil in men and women with renal disease induces differential changes in the DNA methylation of FADS2 and ELOVL5 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e109896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Calder PC, Kremmyda LS, Vlachava M, Noakes PS, Miles EA. Is there a role for fatty acids in early life programming of the immune system? Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69:373‐380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. du Toit G, Tsakok T, Lack S, Lack G. Prevention of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:998‐1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Allam‐Ndoul B, Guenard F, Barbier O, Vohl MC. Effect of n‐3 fatty acids on the expression of inflammatory genes in THP‐1 macrophages. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Willemsen LE. Dietary n‐3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in allergy prevention and asthma treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;785:174‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials