Abstract

Background

The incidence, treatment and outcome of patients with newly diagnosed gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) were studied in an era known for advances in diagnosis and treatment.

Methods

Nationwide population‐based data were retrieved from the Netherlands Cancer Registry. All patients with GIST diagnosed between 2001 and 2012 were included. Primary treatment, defined as any treatment within the first 6–9 months after diagnosis, was studied. Age‐standardized incidence was calculated according to the European standard population. Changes in incidence were evaluated by calculating the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC). Relative survival was used for survival calculations with follow‐up available to January 2017.

Results

A total of 1749 patients (54·0 per cent male and median age 66 years) were diagnosed with a GIST. The incidence of non‐metastatic GIST increased from 3·1 per million person‐years in 2001 to 7·0 per million person‐years in 2012; the EAPC was 7·1 (95 per cent c.i. 4·1 to 10·2) per cent (P < 0·001). The incidence of primary metastatic GIST was 1·3 per million person‐years, in both 2001 and 2012. The 5‐year relative survival rate increased from 71·0 per cent in 2001–2004 to 81·4 per cent in 2009–2012. Women had a better outcome than men. Overall, patients with primary metastatic GIST had a 5‐year relative survival rate of 48·2 (95 per cent c.i. 42·0 to 54·2) per cent compared with 88·8 (86·0 to 91·4) per cent in those with non‐metastatic GIST.

Conclusion

This population‐based nationwide study found an incidence of GIST in the Netherlands of approximately 8 per million person‐years. One in five patients presented with metastatic disease, but relative survival improved significantly over time for all patients with GIST in the imatinib era.

Short abstract

Surgery improves survival

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, affecting 10–15 people per million per year in Western countries1, 2, 3. The incidence is estimated to be higher for the Asian population at 16–20 per million per year4, 5, whereas it is estimated to be 6·8 per million per year in the USA6. There are no studies available with data on global incidence and prevalence.

The identification of GIST originating from the interstitial cells of Cajal and gain‐of‐functions mutations in KIT and PDGFRA genes was pivotal in defining a specific sarcoma subtype7, 8, 9. Validated immunohistochemical analysis of KIT and DOG1 facilitates the diagnosis of GIST10, 11. The more widely available mutation testing of KIT and PDGFRA genes has led to a better understanding of the clinical application of registered tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) imatinib, sunitinib and regorafenib.

Wild‐type GISTs are nowadays divided into succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)‐competent and SDH‐deficient tumours, with different oncogenic driver mutations in the SDH‐competent group9, 12, 13, 14. It has become increasingly important to genotype GISTs, as not all genotypes respond equally to TKIs. These advances in the diagnosis and treatment of GIST have changed rapidly and dramatically over the past decade13, 15, 16, 17.

The present study analysed the incidence and treatment of GIST in an era with gradual advances in diagnosis, imaging and systemic therapy. In addition, the long‐term outcomes of patients with GIST were analysed in comparison with a nationwide population‐based database.

Methods

Data were retrieved from the nationwide population‐based Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR). Data from the NCR are used both in clinical practice and for research purposes. The NCR regularly receives overviews of patients with newly diagnosed cancer from a nationwide pathology network, in which pathology departments of all Dutch hospitals participate. In addition, the medical records services of hospitals provide overviews of diagnoses of cancer in patients treated within outpatient and hospital settings. Trained data managers extract data on patient and tumour characteristics, and on primary treatment from the medical and pathology records. Data on survival were retrieved by linkage to the nationwide population registries network. Survival time was defined as time from diagnosis to death, or until 1 January 2017 for patients who were still alive.

Different from a recent pathology study from the Netherlands, all patients with a malignant GIST (as defined in ICD‐O‐3, morphology code 8936/3) in 2001–2012 were included for analysis in the study and micro‐GIST were excluded18. As the NCR has been using the ICD‐O‐3 morphology code for GISTs from 2001 onwards, this was chosen as a starting point. In previous versions of the ICD‐O, which were used by the NCR until 2000, no specific morphology code for GIST was available.

As there was no specific TNM classification for GISTs until TNM‐7, stage of disease at diagnosis was categorized as localized or metastatic (including both lymph nodes and/or distant metastases). The pathological stage was used if available; otherwise, the clinical stage was used to categorize patients. Data on mitotic rate are not registered in the NCR. Data on completeness of surgery (R status) and tumour size (T category) were available only from 2010. Data in the NCR encompass primary treatment, defined as the treatment a patient receives within the first 6–9 months after primary diagnosis, and categorized as surgery with or without systemic treatment. No data on diagnosis and treatment of recurrent disease are available in the NCR.

The incidence of GIST was calculated by dividing the annual number of patients with GIST by the number of inhabitants in the Netherlands in that particular year, and age‐standardized according to the European standard population. Changes in incidence were evaluated by calculating the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) with its corresponding 95 per cent c.i.19.

The Cochran–Armitage trend test was used to assess for differences over time. Three time frames of 4 years each were used for analyses, thereby accounting for improvements in diagnosis and application of TKIs.

Relative survival (RS), an internationally accepted method that approaches disease‐specific survival, was used for survival calculations. As survival of certain subgroups of patients with GIST can be very good, the RS rate can exceed 100 per cent if it is greater than the survival of the general population. RS is calculated by dividing the absolute survival in the patient population by the expected survival based on overall mortality of the Dutch population matched for age and sex20. The estimation of RS becomes unreliable when the group size is less than ten patients, in which case the results are not presented.

Results

Incidence

A total of 1749 patients, 945 male and 804 female patients, were diagnosed with GIST between January 2001 and December 2012. At diagnosis, 1286 patients (73·5 per cent) were diagnosed with non‐metastatic GIST, 323 (18·5 per cent) with metastatic GIST, and for 140 patients (8·0 per cent) the disease stage was unknown. The specific distributions of patient sex, age and disease stage are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease stage at diagnosis

| 2001–2004 (n = 446) | 2005–2008 (n = 610) | 2009–2012 (n = 693) | Total (n = 1749) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| Median | 66 | 67 | 66 | 66 |

| 0–44 | 36 (8·1) | 51 (8·4) | 50 (7·2) | 137 (7·8) |

| 45–60 | 135 (30·3) | 168 (27·5) | 182 (26·3) | 485 (27·7) |

| 61–74 | 153 (34·3) | 209 (34·3) | 262 (37·8) | 624 (35·7) |

| ≥ 75 | 122 (27·4) | 182 (29·8) | 199 (28·7) | 503 (28·8) |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 229 : 217 | 348 : 262 | 368 : 325 | 945 : 804 |

| Tumour stage | ||||

| Localized GIST | 283 (63·5) | 464 (76·1) | 539 (77·8) | 1286 (73·5) |

| Metastatic GIST | 90 (20·2) | 109 (17·9) | 124 (17·9) | 323 (18·5) |

| Unknown | 73 (16·4) | 37 (6·1) | 30 (4·3) | 140 (8·0) |

| (y)pT stage * | ||||

| T0 (no tumour after preoperative treatment) | 3 (0·7) | 3 (0·7) | ||

| T1 (< 2 cm) | 16 (3·9) | 16 (3·9) | ||

| T2 (2–5 cm) | 110 (27·0) | 110 (27·0) | ||

| T3 (5–10 cm) | 186 (45·7) | 186 (45·7) | ||

| T4 (> 10 cm) | 79 (19·4) | 79 (19·4) | ||

| Tx (unknown) | 13 (3·2) | 13 (3·2) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Data available only for 407 patients resected in 2010–2012. GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumour.

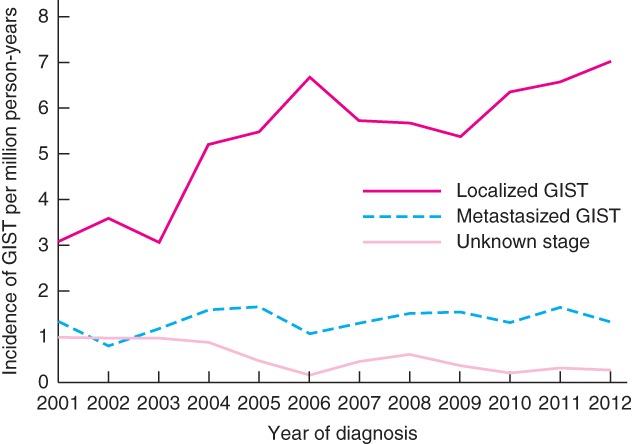

The incidence of non‐metastatic GIST increased from 3·1 per million person‐years in 2001 to 7·0 per million person‐years in 2012 (Fig. 1), and the EAPC was 7·1 (95 per cent c.i. 4·1 to 10·2) per cent (P < 0·001). After 2006, the incidence remained relatively stable. The incidence for unknown disease stage decreased from 1·0 to 0·3 per million person‐years between 2001 and 2012, with an EAPC of −12·1 (−20·0 to −4·3) per cent (P = 0·004). For primary metastatic GIST, the incidence was 1·3 per million person‐years in both 2001 and 2012 (P = 0·175). The EAPC for all patients was 4·2 (2·3 to 6·2) per cent (P = 0·001). The majority of GISTs were located in the stomach (1020 patients, 58·3 per cent), followed by the small intestine and duodenum (411 patients, 23·5 per cent), and rectum (69 patients, 3·9 per cent). In 249 patients (14·2 per cent) the location was unknown or overlapping.

Figure 1.

Incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) in the Netherlands, according to stage at diagnosis

Treatment

The various treatment options undertaken in the 1286 patients (73·5 per cent) with non‐metastatic GIST are reported in Table 2. Only a small number of patients were treated for very small (pT1) GIST lesions (3·9 per cent). The majority of patients (922, 71·7 per cent) were operated on without receiving any systemic therapy. In the first period (2001–2004), 16 patients (5·7 per cent) were treated with some form of preoperative and/or postoperative systemic treatment. This increased to 79 (17·0 per cent) and 103 (19·1 per cent) respectively in the subsequent time periods of 2005–2008 and 2009–2012. Of all 57 patients treated with preoperative imatinib in 2010–2012 who underwent surgery within 6–9 months after diagnosis, three patients had a complete pathological response after resection. From 2010 onwards, the NCR contained data on completeness of resection; 323 (79·4 per cent) of the 407 resected patients had an R0 resection and 39 (9·6 per cent) an R1–R2 resection.

Table 2.

Treatment of patients with a localized gastrointestinal stromal tumour in the first 6–9 months after diagnosis

| 2001–2004 (n = 283) | 2005–2008 (n = 464) | 2009–2012 (n = 539) | Total (n = 1286) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery, no systemic therapy | 229 (80·9) | 335 (72·2) | 358 (66·4) | 922 (71·7) |

| Surgery and preoperative systemic therapy | 10 (3·5) | 36 (7·8) | 40 (7·4) | 86 (6·7) |

| Surgery and postoperative systemic therapy | 6 (2·1) | 39 (8·4) | 49 (9·1) | 94 (7·3) |

| Surgery and preoperative and postoperative systemic therapy | 0 (0) | 4 (0·9) | 14 (2·6) | 18 (1·4) |

| Systemic therapy, no surgery | 21 (7·4) | 36 (7·8) | 48 (8·9) | 105 (8·2) |

| Other or no treatment | 17 (6·0) | 14 (3·0) | 30 (5·6) | 61 (4·7) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

The different treatment modalities for the 323 patients (18·5 per cent) with a primary metastatic GIST are shown in Table 3. The proportion of patients who received systemic treatment with no surgery in the 6–9‐month interval after diagnosis increased from 32 per cent in 2001–2004 to 57·3 per cent in 2009–2012, and presumably included patients treated with neoadjuvant imatinib who had not yet undergone surgery.

Table 3.

Treatment of patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumour in the first 6–9 months after diagnosis

| 2001–2004 (n = 90) | 2005–2008 (n = 109) | 2009–2012 (n = 124) | Total (n = 323) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery, no systemic therapy | 21 (23) | 10 (9·2) | 14 (11·3) | 45 (13·9) |

| Surgery and preoperative systemic therapy | 4 (4) | 8 (7·3) | 5 (4·0) | 17 (5·3) |

| Surgery and postoperative systemic therapy | 6 (7) | 16 (14·7) | 16 (12·9) | 38 (11·8) |

| Surgery and preoperative and postoperative systemic therapy | 1 (1) | 1 (0·9) | 7 (5·6) | 9 (2·8) |

| Systemic therapy, no surgery | 29 (32) | 61 (56·0) | 71 (57·3) | 161 (49·8) |

| Other or no treatment | 29 (32) | 13 (11·9) | 11 (8·9) | 53 (16·4) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Relative survival

Median follow‐up was 69·9 (range 0–192·7) months for all patients. The 5‐year RS rate for all patients increased from 71·0 (95 per cent c.i. 65·6 to 76·0) per cent in 2001–2004 to 81·4 (77·3 to 85·1) per cent in 2009–2012 (Table 4). Women had a better 5‐year RS rate than men: 81·3 (77·6 to 84·7) versus 74·9 (71·2 to 78·4) per cent respectively. As the survival of patients with small tumours (pT1–2) was better than that of the general population, the RS rate exceeded 100 per cent. Patients with a gastric GIST had a 5‐year RS rate of 84·5 per cent versus 78·2, 76·1 and approximately 50 per cent for GISTs of the small intestine/duodenum, rectum and other GI locations respectively. Patients with a non‐metastatic GIST had a 5‐year RS rate of 88·8 (86·0 to 91·4) per cent. Of patients with a localized GIST, those who received surgery only had a better RS than patients who had systemic therapy alone or a combination of surgery and systemic therapy. For patients with a primary metastatic GIST, the 5‐year RS rate was 48·2 (42·0 to 54·2) per cent. Patients who received systemic therapy before and/or after surgery for primary metastatic GIST had a better RS rate than those who had surgery or systemic therapy alone: 77·4 versus 67·0 and 39·7 per cent respectively.

Table 4.

Relative survival of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumour according to Netherlands Cancer Registry standards

| Survival (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | |

| Time interval | ||||

| 2001–2004 | 446 | 85·4 (81·5, 88·7) | 77·8 (73·0, 82·1) | 71·0 (65·6, 76·0) |

| 2005–2008 | 610 | 90·3 (87·4, 92·8) | 84·0 (80·1, 87·4) | 79·0 (74·5, 83·1) |

| 2009–2012 | 693 | 93·2 (90·7, 95·2) | 85·1 (81·5, 88·2) | 81·4 (77·3, 85·1) |

| Sex | ||||

| M | 945 | 89·5 (87·1, 91·6) | 80·7 (77·5, 83·7) | 74·9 (71·2, 78·4) |

| F | 804 | 91·1 (88·7, 93·1) | 85·4 (82·5, 88·2) | 81·3 (77·6, 84·7) |

| Location | ||||

| Stomach | 1020 | 93·1 (91·1, 94·8) | 87·7 (84·9, 90·2) | 84·5 (81·2, 87·6) |

| Small intestine + duodenum | 411 | 90·9 (87·4, 93·7) | 83·8 (79·2, 87·8) | 78·2 (72·8, 83·6) |

| Rectum | 69 | 91·8 (81·1, 97·6) | 84·1 (71·2, 93·2) | 76·1 (61·8, 87·2) |

| Other | 80 | 71·0 (59·2, 80·2) | 58·6 (46·0, 69·6) | 50·4 (37·7, 62·5) |

| Overlapping + GI location not otherwise specified | 169 | 79·4 (72·0, 85·2) | 62·3 (53·8, 70·0) | 50·6 (41·8, 59·1) |

| Disease stage | ||||

| Non‐metastatic | 1286 | 95·4 (93·8, 96·7) | 90·8 (88·5, 92·9) | 88·8 (86·0, 91·4) |

| Metastatic | 323 | 81·1 (76·1, 85·3) | 60·8 (54·8, 66·4) | 48·2 (42·0, 54·2) |

| Unknown | 140 | 63·2 (54·3, 71·1) | 60·6 (51·1, 69·2) | 46·7 (37·2, 56·0) |

| (y)pT stage * | ||||

| T0 (no tumour after preoperative treatment) | 3 | † | † | † |

| T1–2 (< 5 cm) | 126 | 101·0 (96·2, 101·7) | 101·2 (95·2, 104·0) | 102·4 (95·0, 106·6) |

| T3 (5–10 cm) | 186 | 97·1 (92·6, 99·7) | 95·8 (89·7,100·0) | 94·4 (86·9, 100·1) |

| T4 (> 10 cm) | 79 | 102·2‡ | 94·9 (84·9, 100·5) | 86·5 (73·8, 95·5) |

| Tx (unknown) | 13 | † | † | † |

| Radicality * | ||||

| R0 | 323 | 99·2 (96·5,100·6) | 97·6 (93·5, 100·5) | 97·2 (92·1, 101·2) |

| R1/R2 | 39 | 99·4 (84·8, 101·6) | 95·8 (80·0, 102·5) | 83·4 (64·2, 95·9) |

| Unknown | 45 | 97·3 (84·9, 100·6) | 92·0 (77·2, 99·6) | 89·0 (72·2, 99·2) |

| Non‐metastatic GIST | ||||

| Surgery, no systemic therapy | 922 | 97·6 (95·9, 98·8) | 94·9 (92·4, 97·1) | 94·5 (91·4, 97·2) |

| Surgery and systemic therapy | 198 | 97·5 (93·5, 99·5) | 92·5 (86·9, 96·5) | 90·4 (83·9, 95·3) |

| Systemic therapy, no surgery | 105 | 88·6 (80·0, 94·2) | 71·6 (60·6, 80·7) | 61·5 (49·8, 72·2) |

| Other or no therapy | 61 | 66·7 (52·4, 78·3) | 54·3 (38·8, 68·9) | 40·2 (25·0, 56·7) |

| Metastatic GIST | ||||

| Surgery, no systemic therapy | 45 | 86·9 (72·2, 95·0) | 76·0 (59·3, 87·7) | 67·0 (49·3, 81·2) |

| Surgery and systemic therapy | 64 | 96·6 (87·3, 99·8) | 89·7 (78·0, 96·5) | 77·4 (63·6, 87·5) |

| Systemic therapy, no surgery | 161 | 86·0 (79·2, 91·0) | 55·4 (46·9, 63·4) | 39·7 (31·4, 48·1) |

| Other or no therapy | 53 | 41·6 (27·9, 55·0) | 27·7 (15·8, 41·4) | 21·0 (10·3, 34·8) |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Data available only for 407 patients resected in 2010–2012.

Owing to low numbers of patients, relative survival could not be calculated accurately.

As no deaths occurred during the first year, confidence intervals could not be calculated. GI, gastrointestinal; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumour.

Discussion

Since the introduction of imatinib in 2001 and the improved diagnosis of GIST as a distinct histopathological entity, both diagnosis and treatment of patients with GIST have changed dramatically. The present study showed the current incidence of GIST to be approximately 8 per million population annually in the Netherlands, comparable to data from other Western countries1, 2, 3, 21. There is considerable variation in the incidence of GIST reported from different countries, which can be explained by a number of factors. The diagnostic criteria have improved over time as GISTs were commonly misdiagnosed before 2001, and the immunohistochemical identification of KIT and DOG1 expression has made the reliable diagnosis of GIST possible7, 10, 11, 22. Therefore, patients with a GIST or GIST‐like tumour diagnosed before 2001 were excluded from the present study, but will have been included in some international reports4, 5. Not all countries have established cancer registries that register all GISTs, with the consequence that smaller, low‐risk tumours may not have been reported1, 23, 24. Another reason for the difference in incidence might be the lack of registries that score GISTs as separate entities.

Patients with non‐metastatic GIST demonstrated an increased incidence from 3·1 in 2001 to 7·0 in 2012 per million person‐years, with a significant increase in the EAPC of 7·1 per cent. However, the number of patients with unknown stage presentation decreased during the same period owing to better staging and registration; this might partly explain the increased EAPC for localized GIST. From 2006 onwards, the incidence remained stable.

Risk classification of GIST has developed over time, including not only tumour size, but also location and mitotic rate. More recently, tumour rupture and GIST genotype have been added to risk classifications25, 26, 27, 28, 29. High tumour mitotic count, non‐gastric location, large tumour size, rupture during surgery, and adjuvant imatinib for 12 rather than 36 months, were independently associated with a lower recurrence‐free survival rate in patients with GIST29, 30.

A limitation of the present study is that the NCR database lacks information on mitotic rate and tumour rupture, although data on tumour size, sex, location, stage and completeness of resection are available, and were recognized as significant prognostic factors. Other studies6, 31, 32 have also shown patient sex to be a prognostic factor in GIST. The BRF14 trial of the French Sarcoma Group32, which solely included patients with metastatic disease who were started on imatinib, showed a highly significant 5‐year survival benefit for women of 76·5 per cent, versus 53·5 per cent in men. A clear explanation for this sex difference has not yet been found, but the present data showed a similar favourable outcome for women.

Surgery is the most important treatment modality leading to cure in low‐risk tumours. In patients with low‐grade GISTs, 5‐year survival rates as high as 95–100 per cent have been reported in the literature29, and this was also demonstrated in the present cohort. For high‐risk patients, the introduction of adjuvant imatinib has also led to improved survival rates. The stomach is the most commonly affected GI site in patients with a localized GIST, and is associated with the most favourable prognosis, with a 5‐year survival rate of 84·5 per cent reported in the present study. This is comparable with survival data from other studies33, including a large cohort from Korea and Japan34. There may be a bias in these survival rates when compared to other GI locations, because gastric GISTs are generally discovered at an earlier disease stage. In the present study, only 3·9 per cent of removed tumours were smaller than 2 cm (pT1), and the majority of patients with non‐metastatic GIST were treated with surgery alone. An increasing number of patients with larger tumours were treated with preoperative and/or postoperative systemic treatment. This is explained partly by adjuvant treatment with imatinib for high‐risk patients, as demonstrated by Joensuu and colleagues30. Patients with locally advanced GISTs have also increasingly been treated with preoperative imatinib, leading to excellent downsizing and reduction of peroperative tumour rupture35, 36. In the present study, earlier cohorts of patients with high‐risk GIST treated before 2012 did not receive adjuvant imatinib, which may have had an impact on the survival results of high‐risk patients in that period.

The annual incidence of patients presenting with metastatic GIST remained fairly constant over time, with a non‐significant change in the EAPC of 2·4 per cent. The increased use of TKIs in patients with metastatic GIST improved their overall survival significantly17, 37. Before TKIs were available, patients with metastatic GIST had a median survival of 10–20 months38, 39, 40, but this has subsequently increased to more than 4 years, with further improvements in survival over time and differences dependent on molecular subtypes32, 41. The reported 5‐year survival rate of 48·2 per cent for patients with primary metastasized GIST in the present study is in line with the outcome data of these clinical studies17, 37, 41, which is remarkable as the NCR encompasses population‐based data. All patients, including the elderly and patients with very advanced disease or severe co‐morbidity, are included in the nationwide database, whereas such patients are usually excluded from clinical trials.

In the present population, patients with metastatic GIST who underwent surgery with or without systemic therapy had much higher 5‐year RS rates than patients treated with systemic therapy alone (77·4 versus 67·0 and 39·7 per cent respectively). This could be a result of patient selection and bias, although other studies42, 43 have demonstrated an indication for surgery in metastatic GIST, as long as the patient does not have progressive disease. In the NCR database, treatment data are recorded for a maximum of 9 months after diagnosis, which means information on surgery beyond 9 months is lacking, particularly after preoperative systemic treatment. Not only patients with local recurrence or intra‐abdominal metastatic lesions were operated on, but also those with hepatic metastases treated with both systemic treatment and surgery, leading to excellent long‐term survival in carefully selected patients44, 45. Treatment within the context of multidisciplinary teams with expertise in GIST and in clinical studies remains crucial for further improvement in the outcome of patients with GIST46.

The present study demonstrates a stable incidence of GIST in the Netherlands of approximately 8 per million person‐years, with one in five patients presenting with metastatic disease. Women and patients with gastric GIST have the best prognosis. In the imatinib era, RS has improved significantly over time for all patients with GIST.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Snapshot quiz 18/8

References

- 1. Soreide K, Sandvik OM, Soreide JA, Giljaca V, Jureckova A, Bulusu VR. Global epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST): a systematic review of population‐based cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol 2016; 40: 39−46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nilsson B, Bumming P, Meis‐Kindblom JM, Oden A, Dortok A, Gustavsson B et al Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era – a population‐based study in western Sweden. Cancer 2005; 103: 821−829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goettsch WG, Bos SD, Breekveldt‐Postma N, Casparie M, Herings RM, Hogendoorn PC. Incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumours is underestimated: results of a nation‐wide study. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41: 2868−2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chiang NJ, Chen LT, Tsai CR, Chang JS. The epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Taiwan, 1998–2008: a nation‐wide cancer registry‐based study. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nomura E, Ioka A, Tsukuma H. Incidence of soft tissue sarcoma focusing on gastrointestinal stromal sarcoma in Osaka, Japan, during 1978–2007. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013; 43: 841−845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ma GL, Murphy JD, Martinez ME, Sicklick JK. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the era of histology codes: results of a population‐based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 2015; 24: 298−302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, Hashimoto K, Nishida T, Ishiguro S et al Gain‐of‐function mutations of c‐kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 1998; 279: 577−580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, McGreevey L, Chen CJ, Joseph N et al PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 2003; 299: 708−710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rubin BP, Heinrich MC. Genotyping and immunohistochemistry of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an update. Semin Diagn Pathol 2015; 32: 392−399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. West RB, Corless CL, Chen X, Rubin BP, Subramanian S, Montgomery K et al The novel marker, DOG1, is expressed ubiquitously in gastrointestinal stromal tumors irrespective of KIT or PDGFRA mutation status. Am J Pathol 2004; 165: 107−113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Espinosa I, Lee CH, Kim MK, Rouse BT, Subramanian S, Montgomery K et al A novel monoclonal antibody against DOG1 is a sensitive and specific marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2008; 32: 210−218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boikos SA, Pappo AS, Killian JK, LaQuaglia MP, Weldon CB, George S et al Molecular subtypes of KIT/PDGFRA wild‐type gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a report from the National Institutes of Health gastrointestinal stromal tumor clinic. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2: 922–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Demetri GD, Garrett CR, Schoffski P, Shah MH, Verweij J, Leyvraz S et al Complete longitudinal analyses of the randomized, placebo‐controlled, phase III trial of sunitinib in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor following imatinib failure. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 3170−3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Demetri GD, Reichardt P, Kang YK, Blay JY, Rutkowski P, Gelderblom H et al; GRID study investigators . Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013; 381: 295−302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cassier PA, Fumagalli E, Rutkowski P, Schoffski P, Van Glabbeke M, Debiec‐Rychter M et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Outcome of patients with platelet‐derived growth factor receptor alpha‐mutated gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 4458−4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reichardt P, Demetri GD, Gelderblom H, Rutkowski P, Im SA, Gupta S et al Correlation of KIT and PDGFRA mutational status with clinical benefit in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated with sunitinib in a worldwide treatment‐use trial. BMC Cancer 2016; 16: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verweij J, Casali PG, Zalcberg J, LeCesne A, Reichardt P, Blay JY et al Progression‐free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high‐dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet 2004; 364: 1127−1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Verschoor AJ, Boveé JVMG, Overbeek LIH, The PALGA Group , Hogendoorn PCW, Gelderblom H. The incidence, mutational status, risk classification and referral pattern of gastro‐intestinal stromal tumours in the Netherlands: a nationwide pathology registry (PALGA) study. Virchows Arch 2018; 472: 221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Estève J, Benhamou E, Raymond L. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. Volume IV. Descriptive Epidemiology. IARC Scientific Publications: Lyon, 1994: 1−302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hakulinen T, Abeywickrama KH. A computer program package for relative survival analysis. Comput Programs Biomed 1985; 19: 197−207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tran T, Davila JA, El‐Serag HB. The epidemiology of malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an analysis of 1458 cases from 1992 to 2000. Am J Gastroentrol 2005; 100: 162−168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miettinen M, Wang ZF, Lasota J. DOG1 antibody in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a study of 1840 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33: 1401−1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barrios CH, Blackstein ME, Blay JY, Casali PG, Chacon M, Gu J et al The GOLD ReGISTry: a global, prospective, observational registry collecting longitudinal data on patients with advanced and localised gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51: 2423−2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi AH, Hamner JB, Merchant SJ, Trisal V, Chow W, Garberoglio CA et al Underreporting of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: is the true incidence being captured? J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 19: 1699−1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ et al Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum Pathol 2002; 33: 459−465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol 2006; 23: 70−83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol 2008; 39: 1411–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gold JS, Gönen M, Gutiérrez A, Broto JM, García‐del‐Muro X, Smyrk TC et al Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for recurrence‐free survival after complete surgical resection of localised primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10: 1045–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Hall KS, Hartmann JT, Pink D, Schutte J et al Risk factors for gastrointestinal stromal tumor recurrence in patients treated with adjuvant imatinib. Cancer 2014; 120: 2325−2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, Reichardt A, Hartmann JT, Pink D et al Adjuvant imatinib for high‐risk GI stromal tumor: analysis of a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 244−250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kramer K, Knippschild U, Mayer B, Bogelspacher K, Spatz H, Henne‐Bruns D et al Impact of age and gender on tumor related prognosis in gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST). BMC Cancer 2015; 15: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patrikidou A, Domont J, Chabaud S, Ray‐Coquard I, Coindre JM, Bui‐Nguyen B et al; French Sarcoma Group. Long‐term outcome of molecular subgroups of GIST patients treated with standard‐dose imatinib in the BFR14 trial of the French Sarcoma Group. Eur J Cancer 2016; 52: 173−180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Das A, Wilson R, Biankin AV, Merrett ND. Surgical therapy for gastrointestinal stromal tumours of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13: 1220−1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, Lee HJ, Sohn TS, Hyung WJ et al Long‐term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study from Korea and Japan. Medicine 2015; 94: e1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tielen R, Verhoef C, van Coevorden F, Gelderblom H, Sleijfer S, Hartgrink HH et al Surgical treatment of locally advanced, non‐metastatic, gastrointestinal stromal tumours after treatment with imatinib. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013; 39: 150−155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rutkowski P, Gronchi A, Hohenberger P, Bonvalot S, Schoffski P, Bauer S et al Neoadjuvant imatinib in locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): the EORTC STBSG experience. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20: 2937−2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, Ryan CW, von Mehren M, Benjamin RS et al Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 626−632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg 2000; 231: 51−58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Joensuu H, Fletcher C, Dimitrijevic S, Silberman S, Roberts P, Demetri G. Management of malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Lancet Oncol 2002; 3: 655−664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gold JS, van der Zwan SM, Gönen M, Maki RG, Singer S, Brennan MF et al Outcome of metastatic GIST in the era before tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14: 134−142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Casali PG, Zalcberg J, Le Cesne A, Reichardt P, Blay JY, Lindner LH et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group, Italian Sarcoma Group, and Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group. Ten‐year progression‐free and overall survival in patients with unresectable or metastatic GI stromal tumors: long‐term analysis of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Italian Sarcoma Group, and Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group intergroup phase III randomized trial on imatinib at two dose levels. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 1713−1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Keung EZ, Fairweather M, Raut CP. The role of surgery in metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2016; 17: 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tielen R, Verhoef C, van Coevorden F, Gelderblom H, Sleijfer S, Hartgrink HH et al Surgery after treatment with imatinib and/or sunitinib in patients with metastasized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: is it worthwhile? World J Surg Oncol 2012; 10: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seesing MF, Tielen R, van Hillegersberg R, van Coevorden F, de Jong KP, Nagtegaal ID et al; Dutch Liver Surgery Working Group . Resection of liver metastases in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the imatinib era: a nationwide retrospective study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016; 42: 1407−1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vassos N, Agaimy A, Hohenberger W, Croner RS. Management of liver metastases of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). Ann Hepatol 2015; 14: 531−539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cioffi A, Maki RG. GI stromal tumors: 15 years of lessons from a rare cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 1849−1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]