Abstract

Spontaneous preterm birth remains the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, and accounts for a significant global health burden. Several obstetric strategies to screen for spontaneous preterm delivery, such as cervical length and fetal fibronectin measurement, have emerged. However, the effectiveness of these strategies relies on their ability to accurately predict those pregnancies at increased risk for spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB). Transvaginal cervical shortening is predictive of preterm birth and when coupled with appropriate preterm birth prevention strategies, has been associated with reductions in SPTB in asymptomatic women with a singleton gestation. The use of qualitative fetal fibronectin may be useful in conjunction with cervical length assessment in women with acute preterm labor symptoms, but data supporting its clinical utility remain limited. As both cervical length and qualitative fetal fibronectin have limited capacity to predict preterm birth, further studies are needed to investigate other potential screening modalities.

Keywords: Spontaneous preterm birth, Cervical length, Fetal fibronectin

Introduction

Spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) remains the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality in many parts of the world, including the United States.1 The pathogenesis of SPTB is complex and multifactorial. There are many risk factors, both proven and postulated, that have been associated with SPTB. Still, the majority of SPTB occur in women without any identifiable risk factors. Furthermore, given the complexity of the processes that result in SPTB, some women destined to deliver preterm are not offered potentially effective interventions while others destined for term deliveries are exposed to the risks and costs of various interventions without potential benefit.

There are now several strategies available for primary prevention (i.e., contraception to achieve an optimal inter- birth interval, utilization of single embryo transfers when conception is attempted via in vitro fertilization, 17-alpha- hydroxyprogesterone caproate, and smoking cessation) and secondary prevention (i.e., vaginal progestens, cervical cerclage, and tocolysis) of preterm delivery. However, the effectiveness of these interventions depends on the ability to accurately predict which pregnancies are at increased risk of preterm delivery. Furthermore, the most successful efforts to mitigate the consequences of SPTB have been to optimize neonatal outcomes, but even these interventions can be limited by advanced stage of labor or the difficulty of distinguishing irrelevant preterm contractions with true preterm labor. As such, there is an important need for prediction tools that can help guide the management of women at risk for SPTB. The screening modalities that have garnered the most investigation to the present time are assessments of cervical length and fetal fibronectin (Table).

Table –

Test characteristics of cervical length measurement and fetal fibronectin for prediction of preterm birth.

| Reference | Test cutoff | Definition PTB (w) | Prevalence of PTB (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic women with singleton gestation | |||||||

| Cervical length (mm) | |||||||

| No prior PTB | |||||||

| Iams et al2 | o20 | o35 | 4 | 23 | 97 | 26 | 97 |

| Taipale et al21 | ≤25 | o37 | 2 | 6 | 100 | 39 | 99 |

| Heath et al22 | ≤15 | ≤32 | 2 | 58 | 99 | 52 | 99 |

| Hassan et al23 | ≤15 | ≤32 | 4 | 8 | 99 | 47 | 97 |

| Prior PTB | |||||||

| Guzman et al10 | o25 | o34 | 12 | 76 | 68 | 20 | 96 |

| o15 | 81 | 72 | 29 | 96 | |||

| Owen et al12 | o25 | o35 | 26 | 19 | 98 | 75 | 77 |

| Fetal fibronectin (qualitative, ng/mL) | |||||||

| Goldenberg et al57 | Positive | o34 | 8 | 23 | 97 | 25 | NA |

| Leitich et al58 | Single sampling | o34 | Varied | 41 | 94 | NA | NA |

| o37 | 26 | 90 | NA | NA | |||

| Serial sampling | o34 | Varied | 78 | 57 | NA | NA | |

| o37 | 71 | 76 | NA | NA | |||

| Women with singleton gestation with threatened PTL | |||||||

| Cervical length (mm) | |||||||

| Palacio et al38 | o25 | o36 | 15 | 53 | 81 | 34 | 90 |

| Iams et al39 | o30 | o36 | 40 | 100 | 44 | 55 | 100 |

| Rizzo et al46 | ≤20 | o37 | 43 | 68 | 79 | 71 | 76 |

| Tsoi et al55 | ≤15 | o37 (delivery within 7d) |

8 | 94 | 86 | 37 | 99 |

| Ness et al56 | o20 | o37 | 25 | 36 | 87 | 47 | 81 |

| Fetal fibronectin (qualitative, ng/mL) | |||||||

| Deshpande et al51 | Positive | Within 7–10 d | Varied | 77 | 83 | NA | NA |

| Ness et al56 | Positive | Within 14 d | 3 | 67 | 82 | 11 | 99 |

PTB ¼ preterm birth; w ¼ weeks; PPV ¼ positive predictive value; NPV ¼ negative predictive value; FFN ¼ fetal fibronectin; d ¼ days.

Cervical length measurement

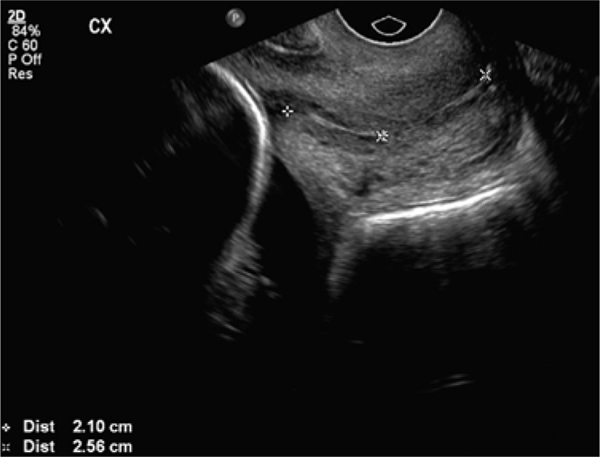

A short cervical length (CL) assessment by transvaginal ultrasound between 16 and 24 weeks of gestation is a reasonably accurate predictor of SPTB.2 The risk of SPTB is inversely proportional to the CL; those with the shortest CL have the highest risk of SPTB, regardless of reproductive history.2 Depending on the population studied and the gestational age at assessment, the clinical cut-off to define a “short” CL has ranged from 15 to 30 mm in the existing literature.2–5 Transvaginal ultrasound is considered the ‘gold standard’ modality to measure CL. With an emptied bladder, the vaginal transducer should be introduced into the anterior fornix of the vagina and positioned so that the endocervical canal is visualized. The image is enlarged to fill at least half of the screen and calipers are placed at the internal and external os to obtain the CL measurement. If the cervical os is curved, the sum of two separate straight lines can be utilized (Fig.). Compared to transabdominal ultrasound, transvaginal ultra- sound is highly reproducible with measurements not limited by maternal obesity, cervical position, or obstructive shadowing from fetal parts.6 Furthermore, initial surveillance with transabdominal ultrasound followed by transvaginal measurements for those with suspicion of a short cervix is not cost-effective.7 Therefore, in the remainder of this document, the term ‘CL’ will assume a transvaginal approach.

Fig. –

Transvaginal ultrasound showing cervical length measured with calipers (Courtesy: Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine).

Women with a singleton pregnancy and a history of prior preterm birth

A history of a prior SPTB is one of the strongest known risk factors for SPTB.8,9 In addition, women with a history of a prior SPTB and a short CL seem to be at the highest risk.10 In the multicenter Preterm Prediction Study,11 the predicted preterm birth (PTB) recurrence risk increased as CL shortened, regardless of fetal fibronectin result. Furthermore, a prospective blinded observational study was conducted in which women with a previous SPTB o 32 weeks gestation and a current singleton pregnancy underwent serial CL assessments.12 The investigators found that CL o 25 mm as a single measurement at 16–18 weeks gestation was associated with a relative risk for SPTB of 3.3 (95% CI: 2.1–5.0; sensitivity ¼ 19%; specificity ¼ 98%; positive predictive value ¼ 75%), and the inclusion of serial observations of CL until 23 weeks 6 days gestation significantly improved the prediction of SPTB in a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis com- pared to an isolated CL measurement (p ¼ 0.03).

A multicenter randomized control trial (RCT) examined the role of serial CL screening with cerclage placement for short CL among women with a singleton pregnancy and a prior PTB o34 weeks gestation.13 Women underwent serial CL measurement once every 2 weeks, starting at 16 weeks until 23 weeks 6 days gestation. For women with a cervical length between 25 and 29 mm, the screening frequency was increased to weekly. If the CL was o25 mm, women were randomized to cerclage placement or expectant management. While there was no significant difference detected in the primary study outcome of PTB o 35 weeks (RR 0.78; 95% CI: 0.58–1.04), cerclage placement was associated with significant reductions in PTB o 24 weeks gestation (RR 0.44; 95% CI: 0.21–0.92), PTB o 37 weeks gestation (RR 0.75; 95% CI: 0.60–0.94) as well as perinatal death (RR 0.54; 95% CI: 0.29–0.99). In the planned secondary analysis,13 cerclage placement for CL o 15 mm was associated with a significant decreased in the primary outcome of PTB o 35 weeks gestation (RR 0.23; 95% CI: 0.08–0.66). Subsequent met-analyses of RCTs showed similar findings.14,15 Consequently, serial CL screening for women with a singleton pregnancy and a history of prior SPTB is recommended.16 Based on the existing literature, it would be prudent to perform serial assessment of CL from 16–24 weeks gestation in women with a history of SPTB o 34 weeks gestation with a plan for an ultrasound-indicated cerclage if a short cervix (CL o 25 mm) is identified. There is insufficient literature to support an ultrasound-indicated cerclage if the prior SPTB occurred between 34 and 37 weeks gestation.

Women with a singleton pregnancy without a history of a prior preterm birth

Women with a current singleton pregnancy without a history of a prior PTB are generally considered to be at lower risk of SPTB.17 Unfortunately, this “low-risk” group still accounts for the majority of women who ultimately experience SPTB.18 Without known risk factors that can be derived from their reproductive history, CL can be useful for risk stratification in this population.19–23 The finding of a short CL, regardless of prior pregnancy history and other clinical risk factors, has been consistently associated with an increased risk of SPTB.2 In a secondary analysis of a RCT of nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies and a CL o 30 mm who received either 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate or placebo, logistic regression analysis including multiple potential risk factors revealed that only CL was associated with SPTB (OR 1.06 per 1-mm decrease, 95% CI: 1.02–1.10).5

Importantly, it has been shown in two RCTs that utilized universal CL screening in large cohorts,3,4 that treatment with vaginal progesterone is associated with an approximately 40% reduction in the risk of PTB in women with a short cervix (with inclusion criterion of a CL o 15 mm3 or 10–20 mm4). However, it is notable that the frequencies of a CL o 15 mm or CL 10–20 mm in these mostly “low-risk” populations (about 80% of enrolled women had no prior PTB) were 1.7%3 and 2.3%,4 respectively. Furthermore, in subsequent studies of the implementation of universal CL screening programs, the frequency of a short cervix in women without a history of a prior PTB has ranged from 1% to 2% depending on the CL threshold used.24–26 Thus, there remains significant debate about the utility of universal CL screening of women with singleton gestations but without prior PTB for the prevention of PTB given the relatively low frequency of a short CL in this population. Still, a large observational study showed that introduction of an institutional universal CL screening program was associated with a significant decrease in the frequency of PTB o 37 weeks [6.7% vs. 6.0%; adjusted OR 0.82 (95% CI: 0.76–0.88)], o34 weeks [1.9% vs. 1.7%; adjusted OR 0.74 (95% CI: 0.64–0.85)], and o32 weeks gestation [1.1% vs. 1.0%, adjusted OR 0.74 (95% CI: 0.62–0.90)], and the reduction was primarily due to a reduction in SPTB.27 Furthermore, even when taking into account the large number of women needed to screen to identify those at risk, several decision and cost-effectiveness analyses have concluded that universal CL screening for identification and treatment of short CL with vaginal progesterone is cost-effective.28,29 Therefore, while universal CL screening is not mandated by professional societies,16,30–33 implementation of such a screening strategy should be considered given its high predictive value, safe and acceptable technique, and high quality evidence to support efficacy and effectiveness of treatment for positive screens (i.e., CL ≤ 20 mm).

Women with multiple gestations

Women with multiple gestations are more likely to have a short CL and are also at an increased risk of SPTB compared to those with singleton gestations.1 In one large multicenter observational study,19 about 18% of twin gestations had a CL o 25 mm compared to 9% of singletons at 22–24 weeks gestation. Furthermore, the risk of SPTB with a CL o 25 mm was increased 8-fold in twins compared to 6-fold in single- tons. In another prospective study of 1163 twin pregnancies,34 logistic regression analysis demonstrated that the only significant independent predictor of spontaneous preterm delivery in women with twin gestations was CL.

Despite the known increased risk of SPTB in those with multiple gestations, there is an absence of high-quality data for an effective intervention to offer to this population even if a short CL is detected. There are several ongoing RCTs, including a multicenter U.S. trial,35 that are evaluating various interventions (e.g., pessary, progesterone) for women with multiple gestations and shortened CL. However, until there is compelling evidence for an effective intervention for women with multiple gestations, routine CL screening is currently not recommended in this population.30

Threatened preterm labor

It has been suggested that CL measurement could be helpful in the assessment of women with PTL symptoms.36–39 A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs using individual patient-level data concluded that knowledge of CL in women with symptoms of acute PTL was associated with a significant reduction in PTB o 37 weeks gestation (RR 0.64, 95% CI: 0.44–0.94).40 However, the other outcomes, which included PTB o36, o34, o32, o30, and o28 weeks gestation, time from randomization to delivery, time from evaluation to discharge, and other neonatal outcomes were not statistically different between those who had knowledge of CL and those who did not. Thus, the clinical impact of CL measurement in this population remains unclear. Furthermore, in symptomatic women presenting with threatened PTL, CL has not been adequately compared with more traditional clinical findings, such as cervical effacement, dilation, and frequency of contractions. Consequently, there is a lack of compelling evidence for the use of CL measurement alone in women with threatened preterm labor.

Fetal Fibronectin

Fetal fibronectin (FFN) is an extracellular matrix glycoprotein found in the amniotic membranes, decidua, and cytotrophoblasts.41 FFN can be detected in cervical and vaginal secretions in all pregnancies, but elevated levels (≥50 ng/mL at 422 weeks gestation) have been associated with an increased risk of SPTB.42 As such, FFN has traditionally been used as a qualitative binary test that provides a positive or negative result based on a threshold of 50 ng/mL. The efficacy of FFN in the prediction of SPTB has been assessed in several populations that include women with suspected preterm labor and asymptomatic women.

Use of qualitative fetal fibronectin testing alone in symptomatic women with singleton gestations

It was hoped that FFN testing would allow accurate identification of women with true preterm labor versus those with false labor. If true, a negative qualitative FFN result could be used to reassure both providers and patients that a SPTB was not imminent, and a positive result would provide an opportunity for interventions that could improve neonatal outcome and/or potentially allow transfer to a facility with appropriate level neonatal care. Theoretically, this would lead to fewer unnecessary hospital admissions and interventions without increasing the rate of SPTB.

Several observational studies have shown that a positive qualitative FFN result is associated with subsequent SPTB.43–46 In the largest multicenter observational study of women with symptoms suggestive of PTL, compared to patients who had negative FFN results, those who had positive FFN results were more likely to be delivered within 7 days [RR 25.9 (95% CI: 7.8–86)], within 14 days [RR 20.4 (95% CI: 8.0–53)], and before 37 weeks gestation [RR 2.9 (95% CI: 2.2–3.7)].43 However, the predictive value of a positive FFN result was only 13% for delivery within 7 days of presentation. The most promising finding was that the negative predictive value for delivery within 7 days was very high at 499%. But notably, in the study cohort, only 3% actually went on to deliver within 7 days of testing. Furthermore, 73% of the enrolled patients were having o4 contractions per hour and 87% were ≤1 cm dilated. There- fore, it is debatable whether these findings provide additional needed guidance in clinical management.

Despite observational studies that suggested FFN testing may help reduce the use of unnecessary resources,47,48 RCTs have not confirmed these findings.49,50 In a systematic review and cost-analysis of five RCTs and 15 diagnostic test accuracy studies,51 FFN testing had moderate accuracy for predicting PTB, but no RCT reported a significant improvement in maternal or neonatal outcomes. In their base-case cost analysis, there was a modest cost difference in favor of FFN testing, but this was largely dependent on whether or not FFN testing reduced hospital admissions, which varied signifiantly. Furthermore, a 2016 systematic review and meta- analysis of six RCTs with a low risk of bias that included 546 women with singleton gestations who presented with PTL symptoms found that those randomly assigned to the knowledge of FFN results did not have reduced rates of PTB at o37 weeks, o34 weeks, o32 weeks, or o28 weeks compared with the control group.52 Women who were randomly assigned to knowledge of FFN results also had similar rates of hospitalization, use of tocolytics, and receipt of antenatal cortico- steroids when compared with women without knowledge of FFN results. Contrary to prior studies, mean hospital costs were actually slightly higher in the group randomly assigned to knowledge of FFN (mean difference $153, 95% CI $24–$282). In summary, based on the current evidence, there is no reason to justify the routine use of FFN alone in women with threatened PTL.16

Use of qualitative fetal fibronectin testing as an adjunct to cervical length measurement in symptomatic women with singleton gestations

Several observational studies have noted that the combination of CL and FFN assessment may improve prediction of SPTB in women with PTL symptoms, particularly in those with a CL of 15–30 mm (e.g., the “grey zone”).53,54 The largest prospective cohort of 665 women with threatened PTL (≥3 contractions in 30 minutes, intact membranes, cervix o3 cm dilated) were enrolled between 24 and 34 weeks gestation, and underwent CL and FFN assessment at all 10 tertiary perinatal centers in The Netherlands.54 They found that women with a CL ≥ 30 mm or those with a CL 15–30 mm and a negative FFN result were at low risk (defined as o5%) of spontaneous delivery within 7 days. Negative FFN testing in women with a CL between 15 and 30 mm additionally classified 103 women (15% of the cohort) as low risk. How- ever, the overall rate of delivery within 7 days was only 12%, and the combination of CL and FFN only increased the PPV from 0.23 (95% CI: 0.19–0.29) to 0.27 (95% CI: 0.22–0.33).

In contrast, in a multicenter prospective observational study of 195 women presenting with threatened preterm labor (regular contractions, intact membranes, and cervix o3 cm dilated) at 24–36 weeks gestation in the United Kingdom and South Africa, delivery within 7 days was more likely to occur in those with short CL (51.5% (18 of 35) of those with CL o 15 mm vs. 0.6% (1 of 160) of those with CL ≥ 15 mm) than those with a positive FFN (21.2% (18 of 85) of those with positive FFN vs. 0.9% (1 of 110) of those with negative FFN).55 Furthermore, multiple logistic regression analysis demonstrated that CL was the only significant contributor to the prediction of delivery within 7 days, with no significant contribution from FFN positivity or other clinical variables.

While clinical evidence of the predictive value of FFN and CL in prediction of SPTB is conficting, there is compelling evidence that these measures do not translate into improved clinical management. In a single center RCT involving 100 women being evaluated for threatened PTL, physician knowledge of CL and FFN results was not associated with a significant overall effect on length of time for evaluation.56 It was only in the group of women with a CL ≥ 30 mm that the mean time for evaluation was significantly shorter in the knowledge group (1:58 h ± 0:50 vs. 2:53 h ± 0:50, P ¼ .004), but it was institutional protocol that women with a CL ≥ 30 mm were discharged immediately and FFN testing was not per- formed in this group. Therefore, the existing literature remains limited and variable, and there is currently an absence of high-quality data to suggest that the addition of FFN to CL measurement in women with symptoms of preterm labor significantly improves the prediction of SPTB or is helpful in changing clinical management.

Asymptomatic women

The use of FFN in asymptomatic women was evaluated in the multicenter Preterm Prediction Study in which 2929 women who were asymptomatic at enrollment were routinely screened every two weeks from 22–24 to 30 weeks gestation for cervical and vaginal FFN.57 A positive qualitative FFN test at 22–24 weeks gestation predicted more than half of the SPTB o 28 weeks gestation (sensitivity 0.63). However, the positive predictive value (for SPTB o 34 weeks gestation) was low, ranging from 17% to 25% depending on gestational age at the time of sampling.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 studies,58 subgroup analysis showed that the use of single sampling of FFN asymptomatic women had low sensitivities of 26% (95% CI: 5–46) and 41% (95% CI: 23–58) for PTB o 37 weeks and o34 weeks gestation, respectively. However, there was significant heterogeneity among the included studies. Furthermore, while serial FFN testing seemed to improve the performance of the FFN test [sensitivities of 71% (95% CI: 60–82) and 78% (95% CI: 57–99) for PTB o 37 weeks and o34 weeks gestation, respectively], the improvement was moderate at best, and it is dubious that this approach would be cost-effective in asymptomatic women.

Use of quantitative fetal fibronectin testing

Recent studies have shown that quantitative measurement of FFN may improve predictive value compared to the qualitative test that uses 50 ng/mL as the threshold.59–61 In a pre-specified secondary analysis of a prospective blinded study, the positive predictive value for SPTB o 34 weeks gestation increased from 19%, 32%, 61%, and 75% with increasing thresholds (10, 50, 200, and 500 ng/mL, respectively).59 The combination of quantitative FFN testing and CL assessment may further increase predictive value, but data remains limited to preliminary observational studies.62 The use of quantitative FFN remains investigational63 and is not yet commercially available for use in the United States.

Multiple gestations

There is a paucity of data on the predictive ability and usefulness of FFN testing specific to women with multiple gestations. One systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort and cross-sectional studies involving both symptomatic and asymptomatic women with multiple gestations found that FFN testing had limited accuracy in predicting SPTB.64

Given the lack of supporting data, FFN testing in women with multiple gestations is not recommended.

Conclusion

While imperfect, CL measurement is currently the strongest clinical predictor of PTB in asymptomatic pregnant women. The use of FFN, particularly as a quantified value, may be useful in conjunction with CL assessment in women with acute preterm labor symptoms, but data remain limited and further studies are needed before routine implementation occurs. In women with multiple gestations, the utility of CL measurement and FFN remains investigational.

References

- 1.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(12):1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9): 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH, Fetal Medicine Foundation Second Trimester Screening G. Proges- terone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(5):462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, et al. Vaginal progester- one reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, dou- ble-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(1):18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grobman WA, Lai Y, Iams JD, et al. Prediction of spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women with a short cervix. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35(6):1293–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roh HJ, Ji YI, Jung CH, Jeon GH, Chun S, Cho HJ. Comparison of cervical lengths using transabdominal and transvaginal sonography in midpregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32(10): 1721–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller ES, Grobman WA. Cost-effectiveness of transabdominal ultrasound for cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(6):546.e1–546.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spong CY. Prediction and prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esplin MS, O’Brien E, Fraser A, et al. Estimating recurrence of spontaneous preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzman ER, Walters C, Ananth CV, et al. A comparison of sonographic cervical parameters in predicting spontaneous preterm birth in high-risk singleton gestations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18(3):204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: recurrence risk of spontaneous preterm birth. National Institute of Child Health and Human Develop- ment Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(5):1035–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owen J, Yost N, Berghella V, et al. Mid-trimester endovaginal sonography in women at high risk for spontaneous preterm birth. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286(11):1340–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owen J, Hankins G, Iams JD, et al. Multicenter randomized trial of cerclage for preterm birth prevention in high-risk women with shortened midtrimester cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(4):375.e1–375.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berghella V, Odibo AO, To MS, Rust OA, Althuisius SM. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography: meta-analysis of trials using individual patient-level data. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(1):181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berghella V, Rafael TJ, Szychowski JM, Rust OA, Owen J. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography in women with singleton gestations and previous preterm birth: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics TACoO, Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ananth CV, Peltier MR, Getahun D, Kirby RS, Vintzileos AM. Primiparity: an ‘intermediate’ risk group for spontaneous and medically indicated preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20(8):605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrini JR, Callaghan WM, Klebanoff M, et al. Estimated effect of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate on preterm birth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldenberg RL, Iams JD, Mercer BM, et al. The preterm prediction study: the value of new vs standard risk factors in predicting early and all spontaneous preterm births. NICHD MFMU Network. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(2):233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.To MS, Skentou CA, Royston P, Yu CK, Nicolaides KH. Prediction of patient-specific risk of early preterm delivery using maternal history and sonographic measurement of cervical length: a population-based prospective study. Ultra- sound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27(4):362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taipale P, Hiilesmaa V. Sonographic measurement of uterine cervix at 18–22 weeks’ gestation and the risk of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(6):902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heath VC, Southall TR, Souka AP, Elisseou A, Nicolaides KH. Cervical length at 23 weeks of gestation: prediction of sponta- neous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;12(5): 312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan SS, Romero R, Berry SM, et al. Patients with an ultrasonographic cervical length o or ¼15 mm have nearly a 50% risk of early spontaneous preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(6):1458–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Facco FL, Simhan HN. Short ultrasonographic cervical length in women with low-risk obstetric history. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orzechowski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1–523.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid- trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1–365.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cahill AG, Odibo AO, Caughey AB, et al. Universal cervical length screening and treatment with vaginal progesterone to prevent preterm birth: a decision and economic analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(6):548.e1–548.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Werner EF, Hamel MS, Orzechowski K, Berghella V, Thung SF. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: an update. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):554.e1–554.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Electronic address pso McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low- risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2–B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee waoVB. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Berghella V, et al. Practice guidelines for performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(1):116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim K, Butt K, Crane JM. SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline. Ultrasonographic cervical length assessment in predicting preterm birth in singleton pregnancies. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(5):486–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.To MS, Fonseca EB, Molina FS, Cacho AM, Nicolaides KH. Maternal characteristics and cervical length in the prediction of spontaneous early preterm delivery in twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1360–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT02518594, A Trial of Pessary and Progesterone for Preterm Prevention in Twin Gestation with a Short Cervix (PROSPECT); 2015 March 18 [cited 2017 Sept 14]; [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02518594?term=PRO.SPECT&cond=cervical+length&rank=1.

- 36.Gomez R, Galasso M, Romero R, et al. Ultrasonographic examination of the uterine cervix is better than cervical digital examination as a predictor of the likelihood of pre- mature delivery in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(4):956–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okitsu O, Mimura T, Nakayama T, Aono T. Early prediction of preterm delivery by transvaginal ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1992;2(6):402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palacio M, Sanin-Blair J, Sanchez M, et al. The use of a variable cut-off value of cervical length in women admitted for preterm labor before and after 32 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(4):421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iams JD, Paraskos J, Landon MB, Teteris JN, Johnson FF. Cervical sonography in preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(1): 40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berghella V, Palacio M, Ness A, Alfirevic Z, Nicolaides K, Saccone G. Cervical length screening for prevention of pre- term birth in singleton pregnancies with threatened preterm labor: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using individual patient-level data. Ultra- sound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49:322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feinberg RF, Kliman HJ, Lockwood CJ. Is oncofetal fibronectin a trophoblast glue for human implantation? Am J Pathol. 1991;138(3):537–543. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lockwood CJ, Senyei AE, Dische MR, et al. Fetal fibronectin in cervical and vaginal secretions as a predictor of preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(10):669–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peaceman AM, Andrews WW, Thorp JM, et al. Fetal fibronectin as a predictor of preterm birth in patients with symptoms: a multicenter trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(1):13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swamy GK, Simhan HN, Gammill HS, Heine RP. Clinical utility of fetal fibronectin for predicting preterm birth. J Reprod Med. 2005;50(11):851–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skoll A, St Louis P, Amiri N, Delisle MF, Lalji S. The evaluation of the fetal fibronectin test for prediction of preterm delivery in symptomatic patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(3): 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rizzo G, Capponi A, Arduini D, Lorido C, Romanini C. The value of fetal fibronectin in cervical and vaginal secretions and of ultrasonographic examination of the uterine cervix in predicting premature delivery for patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(5): 1146–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giles W, Bisits A, Knox M, Madsen G, Smith R. The effect of fetal fibronectin testing on admissions to a tertiary maternal– fetal medicine unit and cost savings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(2):439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joffe GM, Jacques D, Bemis-Heys R, Burton R, Skram B, Shelburne P. Impact of the fetal fibronectin assay on admissions for preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(3 Pt 1): 581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Plaut MM, Smith W, Kennedy K. Fetal fibronectin: the impact of a rapid test on the treatment of women with preterm labor symptoms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(6):1588–1593. [discussion 1593–1585]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grobman WA, Welshman EE, Calhoun EA. Does fetal fibronectin use in the diagnosis of preterm labor affect physician behavior and health care costs? A randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deshpande SN, van Asselt AD, Tomini F, et al. Rapid fetal fibronectin testing to predict preterm birth in women with symptoms of premature labour: a systematic review and cost analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(40):1–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berghella V, Saccone G. Fetal fibronectin testing for prevention of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with threatened preterm labor: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4): 431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gomez R, Romero R, Medina L, et al. Cervicovaginal fibronectin improves the prediction of preterm delivery based on sonographic cervical length in patients with preterm uterine contractions and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 192(2):350–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Baaren GJ, Vis JY, Wilms FF, et al. Predictive value of cervical length measurement and fibronectin testing in threatened pre-term labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1185–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsoi E, Akmal S, Geerts L, Jeffery B, Nicolaides KH. Sono- graphic measurement of cervical length and fetal fibronectin testing in threatened preterm labor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27(4):368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ness A, Visintine J, Ricci E, Berghella V. Does knowledge of cervical length and fetal fibronectin affect management of women with threatened preterm labor? A randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4):426.e1–426.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, Meis PJ, Copper RL, Das A, McNellis D. The preterm prediction study: fetal fibronectin testing and spontaneous preterm birth. NICHD Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(5 Pt 1): 643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leitich H, Kaider A. Fetal fibronectin—how useful is it in the prediction of preterm birth? Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;110 (suppl 20):66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abbott DS, Radford SK, Seed PT, Tribe RM, Shennan AH. Evaluation of a quantitative fetal fibronectin test for spontaneous preterm birth in symptomatic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(2):122.e1–122.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuhrt K, Unwin C, Hezelgrave N, Seed P, Shennan A. Endo- cervical and high vaginal quantitative fetal fibronectin in predicting preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014; 27(15):1576–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuhrt K, Hezelgrave N, Foster C, Seed PT, Shennan AH. Development and validation of a tool incorporating quantitative fetal fibronectin to predict spontaneous preterm birth in symp- tomatic women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(2):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bruijn MM, Kamphuis EI, Hoesli IM, et al. The predictive value of quantitative fibronectin testing in combination with cervical length measurement in symptomatic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):793.e1–793.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT03062020, New Tool to Predict Risk of Spontaneous Preterm Birth in Asymp- tomatic High-risk Women; 2016 Nov 29 [cited 2017 Sept 14]; [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ ct2/show/NCT03062020?term=quantitative+fetal+fibronectin&rank=1.

- 64.Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R. Cervicovaginal fetal fibronectin for the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth in multiple pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(12):1365–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]