Abstract

BACKGROUND

In 2016, the Microsimulation Screening Analysis‐Colon (MISCAN‐Colon) model was used to inform the US Preventive Services Task Force colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidelines. In this study, 1 of 2 microsimulation analyses to inform the update of the American Cancer Society CRC screening guideline, the authors re‐evaluated the optimal screening strategies in light of the increase in CRC diagnosed in young adults.

METHODS

The authors adjusted the MISCAN‐Colon model to reflect the higher CRC incidence in young adults, who were assumed to carry forward escalated disease risk as they age. Life‐years gained (LYG; benefit), the number of colonoscopies (COL; burden) and the ratios of incremental burden to benefit (efficiency ratio [ER] = ΔCOL/ΔLYG) were projected for different screening strategies. Strategies differed with respect to test modality, ages to start (40 years, 45 years, and 50 years) and ages to stop (75 years, 80 years, and 85 years) screening, and screening intervals (depending on screening modality). The authors then determined the model‐recommended strategies in a similar way as was done for the US Preventive Services Task Force, using ER thresholds in accordance with the previously accepted ER of 39.

RESULTS

Because of the higher CRC incidence, model‐predicted LYG from screening increased compared with the previous analyses. Consequently, the balance of burden to benefit of screening improved and now 10‐yearly colonoscopy screening starting at age 45 years resulted in an ER of 32. Other recommended strategies included fecal immunochemical testing annually, flexible sigmoidoscopy screening every 5 years, and computed tomographic colonography every 5 years.

CONCLUSIONS

This decision‐analysis suggests that in light of the increase in CRC incidence among young adults, screening may be offered earlier than has previously been recommended. Cancer 2018;124:2964‐73. © 2018 The Authors. Cancer published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of American Cancer Society.

Keywords: advisory committees, colorectal neoplasms, early detection of cancer, incidence, models, preventive health services, theoretical

Short abstract

Colorectal cancer incidence has been increasing since the mid‐1990s in adults aged <50 years. A well‐established decision‐analytic modeling approach suggests that in light of this increasing incidence, the optimal age to start colorectal cancer screening is 45 years.

See also pages 2974‐85.

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that in 2018, > 50,000 colorectal cancer (CRC) deaths will occur in the United States,1 making CRC the second most common cause of cancer death in men and women combined.2 CRC death often can be prevented by CRC screening,3 which is recommended from ages 50 years to 75 years by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Cancer Society (ACS).4, 5 For the population as a whole, CRC incidence and mortality have been declining for several decades, much of which is attributed to an increase in CRC screening uptake.2 However, in adults aged <50 years among whom screening currently is not routinely recommended for those at average risk, CRC incidence has been increasing since the mid‐1990s.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Based on national data, CRC now is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the most common cause of cancer death in American men aged <50 years.12, 13

In the recently updated USPSTF guidelines,4 screening was recommended to begin at age 50 years, despite the fact that 2 of 3 colorectal microsimulation models of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) suggested that starting screening at age 45 years provided a more favorable balance between the benefits and burden of screening compared with starting at age 50 years.14 As described in the USPSTF recommendation statement, reasons for not lowering the recommended age to start screening were the lack of agreement between all 3 CISNET models and the limited empirical data related to screening before age 50 years.4 However, accumulating evidence has demonstrated a persistent increase in CRC incidence in adults aged <50 years.2, 6 Although the elevated background risk likely will be carried forward with these generations as they age due to the cohort effect,6 it is unlikely that it will be observed in CRC incidence data for those aged ≥55 years because it is counteracted by the increased uptake of screening in those ages.

The CISNET microsimulation models that were used to inform the 2016 USPSTF CRC screening guidelines were calibrated to CRC incidence rates from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program registries during 1975 through 1979.14 This time frame was chosen because there was little CRC screening in this period. As a result, these models did not account for the recent increase in CRC incidence in individuals aged <50 years. Therefore, at the request of the ACS, we re‐evaluated the optimal age to start screening, age to stop screening, and the screening interval incorporating contemporary trends in young adults to inform the update of the ACS CRC screening guideline.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used the Microsimulation Screening Analysis‐Colon (MISCAN‐Colon) model to evaluate the optimal age to start screening, age to stop screening, and screening interval. First, we adjusted the model to reflect the increased CRC incidence in more recent birth cohorts. Second, the benefits and harms of the different screening strategies were predicted. Third, the balance between the benefits and the burden of screening was used to select model‐recommended strategies. The methods used for these steps are described in the section below. Analyses were similar to those performed to inform USPSTF guideline recommendations (see Supporting Table 1 for a summary of all differences).14

MISCAN‐Colon

The MISCAN‐Colon model used in this study was developed by the Department of Public Health within Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and has been described in detail elsewhere.15, 16 It is part of CISNET, a consortium of cancer decision modelers sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). In brief, the model generates, with random variation, the individual life histories for a large cohort to simulate the US population in terms of life expectancy and cancer risk. Each simulated person ages over time and may develop ≥1 adenomas that can progress from small (≤5 mm) to medium (6‐9 mm) to large (≥10 mm) in size. Some adenomas develop into preclinical cancer, which may progress through stages I to IV. During each disease transition point, CRC may be diagnosed because of symptoms. Survival after clinical diagnosis is determined by the stage at diagnosis, the location of the cancer, and the person's age. Some simulated life histories are altered by screening through the detection and removal of adenomas or diagnosing CRC in an earlier stage, resulting in a better prognosis. Screening also results in high rates of detection and removal (overtreatment) of polyps, the majority of which would not progress to invasive disease, and may result in fatal complications from colonoscopy with polypectomy,15, 17, 18 all of which are considered in the model.

Model incorporation of increase in CRC incidence

The original MISCAN‐Colon model was calibrated to CRC incidence in 1975‐1979. To incorporate the increased CRC incidence in recent birth cohorts, we adjusted the model based on the observed increase since that period as estimated by Siegel et al.6 Age‐period‐cohort modeling of SEER data performed by Siegel et al revealed that the increase in CRC incidence currently is confined to ages <55 years and primarily is the result of a strong birth cohort effect that began in those born in the 1950s. Consequently, these and subsequent generations will carry forward escalated disease risk as they age.6 Affected cohorts are only now reaching the age to initiate screening, which will likely somewhat counteract the trend. In our analyses, we simulated a cohort of adults aged 40 years in 2015, and assumed that this cohort had a 1.591‐fold increased CRC incidence across all ages compared with the original model. This incidence multiplier was based on the incidence rate ratio (IRR) for CRC of the 1935 birth cohort (those aged 40 years in 1975) compared with the 1975 birth cohort (those aged 40 years in 2015).19 In accordance with the data, we assumed that the increase in CRC incidence was mostly confined to an increase in tumors in the rectum and the distal colon.6 In the base case analysis, we assumed that the increase in CRC incidence was caused by a higher prevalence of adenomas. In a sensitivity analysis, we explored how our results differed with the alternative assumption of stable adenoma prevalence, but faster progression to malignancy.

Screening Strategies

Six screening modalities were evaluated: 1) colonoscopy; 2) fecal immunochemical testing (FIT); 3) high‐sensitivity guaiac‐based fecal occult blood testing (HSgFOBT); 4) multitarget stool DNA testing (FIT‐DNA); 5) flexible sigmoidoscopy (SIG); and 6) computed tomographic colonography (CTC). Multiple ages to begin and stop screening and multiple screening intervals were evaluated for each modality (Table 1). Test characteristics are described by Knudsen et al,14 and are presented in Supporting Table 2. A 40‐year‐old US cohort free of CRC was simulated, thereby only evaluating the effect of the different screening strategies in a population of individuals to whom the screening guidelines for average‐risk individuals apply. These 40‐year‐olds were assumed to have a 100% adherence to screening, follow‐up, and surveillance.20

Table 1.

Screening Strategies Evaluated by the Microsimulation Model

| Screening Modality | Age to Start Screening, Years | Age to Stop Screening, Years) | Screening Interval, Years | No. of (Unique) Strategiesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No screening | 1 (1) | |||

| Colonoscopy | 40, 45, 50 | 75, 80, 85 | 5, 10, 15 | 27 (20) |

| Stool‐based tests | ||||

| Fecal immunochemical test | 40, 45, 50 | 75, 80, 85 | 1, 2, 3 | 27 (27) |

| High‐sensitivity guaiac‐based FOBT | 40, 45, 50 | 75, 80, 85 | 1, 2, 3 | 27 (27) |

| Multitarget stool DNA test | 40, 45, 50 | 75, 80, 85 | 1, 3, 5 | 27 (27) |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | 40, 45, 50 | 75, 80, 85 | 5, 10 | 18 (15) |

| Computed tomographic colonography | 40, 45, 50 | 75, 80, 85 | 5, 10 | 18 (15) |

| Total | 145 (132) |

Abbreviation: FOBT, fecal occult blood test.

The number of unique strategies excluded the strategies that overlap (eg, colonoscopy every 10 years from ages 50 to 80 years and from ages 50 to 85 years both include colonoscopies at ages 50, 60, 70, and 80 years and therefore are not unique strategies).

The benefit of screening was measured by the number of life‐years gained (LYG) from the screening strategy, and corrected for life‐years lost due to screening complications. The number of required colonoscopies was used as a measure of the aggregate burden of screening, and included colonoscopies for screening, follow‐up, surveillance, and the diagnosis of symptomatic cancer. Because this measure of burden does not capture the burden of other screening modalities, direct comparisons of the benefit and burden across screening strategies were limited to those with similar noncolonoscopy burden. Therefore, only the stool‐based tests were grouped, which resulted in 4 classes of screening modalities: 1) colonoscopy; 2) stool‐based modalities (FIT, HSgFOBT, and FIT‐DNA); 3) SIG; and 4) CTC.

Efficient and Near‐Efficient Screening Strategies

The LYG and colonoscopy burden were plotted for each screening strategy by class of screening modalities. Strategies providing the largest incremental increase in LYG per additional colonoscopy were connected, thereby composing the efficient frontier. All strategies on the efficient frontier were considered efficient screening options,21 whereas others fell below the frontier and were dominated. Weakly dominated strategies that had LYG within 98% of the efficient frontier were defined as near‐efficient; other strategies below the efficient frontier were considered inefficient. For efficient and near‐efficient strategies, the incremental number of colonoscopies (ΔCOL), the incremental number of LYG (ΔLYG), and the efficiency ratio (ER) (ΔCOL/ΔLYG) relative to the next less effective efficient strategy were calculated.

Model‐Recommended Screening Strategies

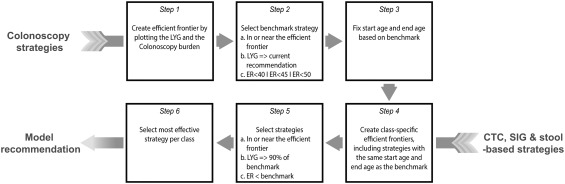

A predefined algorithm was used to select model‐recommended screening strategies (Fig. 1).14 First, the efficient frontier for the colonoscopy strategies was generated (step 1), after which a benchmark colonoscopy screening strategy was selected that 1) was an efficient or near‐efficient colonoscopy screening strategy, 2) had LYG no less than the previously recommended colonoscopy every 10 years from ages 50 to 75 years, and 3) had an efficiency ratio (ER = ΔCOL/ΔLYG) of ≤ 40, 45, or 50 incremental colonoscopies per LYG (step 2). We decided to evaluate different ER thresholds in liaison with recommendations for cost‐effectiveness analysis, for which it is recommended to evaluate multiple willingness‐to‐pay thresholds.22 We analyzed ER thresholds of 40, 45, and 50, in accordance with the efficiency ratio for the MISCAN‐Colon model in the USPSTF analyses, in which 39 was considered an acceptable number of colonoscopies per LYG and 114 was not, suggesting the threshold of an acceptable number of colonoscopies per LYG was in‐between those values.14

Figure 1.

Algorithm used to select model‐recommended strategies. LYG indicates life‐years gained (current recommendation is colonoscopy screening from ages 50 to 75 years every 10 years); ER, efficiency ratio. The ER is calculated as and is an incremental burden‐to‐benefits ratio. Threshold ERs of 40, 45, and 50 colonoscopies per LYG were evaluated. The stool‐based strategies (fecal immunochemical test, high‐sensitivity guaiac‐based fecal occult blood test, and multitarget stool DNA test) were combined into 1 class because they have a similar noncolonoscopy burden. CTC, computed tomographic colonography; SIG, flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Next, the start age and stop age of screening were fixed at those of the colonoscopy benchmark strategy (step 3), because different start ages and stop ages for different screening modalities are not easy to implement in practice because this may complicate the communication between physicians and patients. Simplifying a regimen has been shown to be an important intervention to increase patient adherence,23 and therefore recommending different start ages or stop ages for the different screening modalities may result in lower participation. For the noncolonoscopy screening modalities, within‐class efficient frontiers were created, with the same start age and stop age as the benchmark colonoscopy strategy (step 4), and selected were 1) efficient or near‐efficient strategies that 2) had at least 90% of the LYG compared with the benchmark colonoscopy strategy and 3) had ERs lower than the benchmark colonoscopy strategy (step 5). Among all strategies within a class of screening modality fulfilling all the above criteria, only the most effective strategies were recommended by the model (step 6).

Assumptions Evaluated in the Sensitivity Analyses

Three major assumptions were made that potentially influenced the results, which therefore were explored in the sensitivity analyses. First, as mentioned above, we assumed that the increase in CRC incidence was caused by an increase in adenoma onset in our primary analyses. Therefore, we explored faster adenoma progression to malignancy in a sensitivity analysis. Second, we assumed that the 1975 birth cohort will carry forward the increased CRC incidence as they age. Therefore, we increased incidence only <age 50 years in a sensitivity analysis. Third, we used an IRR of 1.591 because this is applicable to the 1975 birth cohort. Incidence rate ratios of 1.2, 1.3… 2.3 and 2.4 were explored in a sensitivity analysis, with higher ratios being potentially informative for more recent birth cohorts.

RESULTS

A total of 132 unique screening strategies were evaluated (Table 1). The CRC deaths averted per 1000 40‐year‐olds ranged from 25 for triennial HSgFOBT from ages 50 to 75 years to 40 for colonoscopy every 5 years from ages 40 to 85 years (Supporting Table 3). The lifetime number of colonoscopies per 1000 40‐year‐olds, used as a measure of burden, ranged from 1433 for triennial FIT screening from ages 50 to 75 years to 8671 for colonoscopy every 5 years from ages 40 to 85 years, whereas the number of LYG compared with no screening, used to measure benefit, ranged from 284 for triennial HSgFOBT from ages 50 to 75 years to 475 for colonoscopy every 5 years from ages 40 to 85 years (see Supporting Table 3).

Efficient and Near‐Efficient Screening Strategies

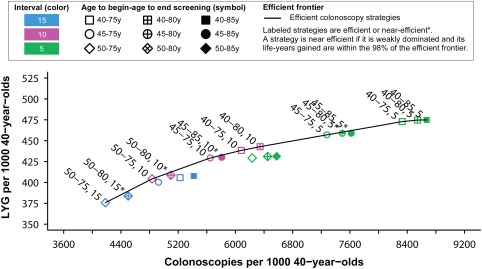

The LYG compared with the number of colonoscopies required and the efficient frontier for the colonoscopy strategies are presented in Figure 2. Nine efficient and 5 near‐efficient (LYG within 98% of the efficient frontier) colonoscopy strategies were identified, in which the ERs (incremental burden‐to‐benefits ratios) for the colonoscopy strategies ranged from 11 colonoscopies per LYG for screening every 15 years from ages 50 to 75 years to 569 for colonoscopy screening every 5 years from ages 40 to 85 years (see Supporting Table 4). The current colonoscopy screening recommendation (screening every 10 years from ages 50‐75 years) was 1 of the 9 efficient strategies and had an ER of 23. The plots of the other screening modalities can be found in Supporting Information Figures 1 to 3. Twenty‐two of 25 stool‐based strategies in or near the efficient frontier were FIT strategies, demonstrating that FIT screening largely dominated the other stool‐based strategies (Supporting Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

Lifetime number of colonoscopies and life‐years gained (LYG) for colonoscopy screening strategies.

Model‐Recommended Strategies

The colonoscopy strategy recommended by the model was screening every 10 years from ages 45 to 75 years with an ER of 32 incremental colonoscopies per LYG (Table 2). This strategy was selected because it was on the efficient frontier and had the highest number of LYG among the strategies with ERs <40 and 45. Compared with the current recommendation (screening every 10 years from ages 50‐75 years), this strategy resulted in 25 (+6.2%) additional LYG accompanied by an increase in 810 (+17%) colonoscopies per 1000 40‐year‐olds.

Table 2.

Outcomes for Screening Strategies With Similar Age to Start and Age to Stop Screening as the Selected Benchmark Colonoscopy Strategy

| Outcomes per 1000 40‐year‐olds | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modality and Age to Start/Age to End/Interval, Years | No. of Stool Tests | No. of SIGs | No. of CTCs | No. of COLs | LYG | Complications | CRC Deaths Averteda | ERb | ER < Benchmarkc | LYG ≥ 90% of Benchmark | Model‐Recommended Strategyd |

| COL | |||||||||||

| COL 45/75/10e | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5646 | 429 | 23 | 37 | 32 | ‐ | ‐ | Yes |

| Stool tests | |||||||||||

| FIT 45/75/3 | 8038 | 0 | 0 | 1619 | 310 | 11 | 27 | 5 | Yes | No | |

| FIT 45/75/2 | 10,973 | 0 | 0 | 1994 | 352 | 13 | 30 | 9 | Yes | No | |

| HSgFOBT 45/75/3 | 7405 | 0 | 0 | 2024 | 310 | 13 | 27 | Dominated | ‐ | No | |

| FIT‐DNA 45/75/5 | 4949 | 0 | 0 | 2157 | 333 | 14 | 29 | Dominated | ‐ | No | |

| HSgFOBT 45/75/2 | 9776 | 0 | 0 | 2516 | 354 | 15 | 30 | Dominated | ‐ | No | |

| FIT‐DNA 45/75/3 | 6644 | 0 | 0 | 2640 | 376 | 16 | 32 | Dominated | ‐ | No | |

| FIT 45/75/1 | 17,835 | 0 | 0 | 2698 | 403 | 16 | 34 | 14 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| HSgFOBT 45/75/1 | 14,366 | 0 | 0 | 3364 | 403 | 18 | 34 | Dominated | ‐ | Yes | |

| FIT‐DNA 45/75/1 | 12,019 | 0 | 0 | 3851 | 426 | 19 | 36 | 50 | No | Yes | |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | |||||||||||

| SIG 45/75/10 | 0 | 2691 | 0 | 3314 | 373 | 19 | 33 | 9 | Yes | No | |

| SIG 45/75/5 | 0 | 3865 | 0 | 3761 | 403 | 20 | 35 | 15 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CT colonography | |||||||||||

| CTC 45/75/10 | 0 | 0 | 3045 | 2106 | 322 | 14 | 29 | 6 | Yes | No | |

| CTC 45/75/5 | 0 | 0 | 4630 | 2666 | 390 | 16 | 34 | 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Abbreviations: COL, colonoscopy; CRC, colorectal cancer; CTC, computed tomographic colonography; ER, efficiency ratio; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; FIT‐DNA, multitarget stool DNA test; HSgFOBT, high‐sensitivity guaiac‐based fecal occult blood test; LYG, life‐years gained; SIG, flexible sigmoidoscopy.

In the absence of screening, the model predicted 45 deaths from CRC.

Calculated as . It is an incremental burden‐to‐benefits ratio.

A strategy can only be recommended by the model if it has an ER lower than the ER of the benchmark strategy (COL every 10 years from ages 45 to 75 years).

A strategy is recommended by the model if it is an efficient or a near‐efficient strategy with a lower burden‐to‐benefits ratio and at least 90% of the LYG compared with the benchmark strategy (COL screening every 10 years from ages 45 to 75 years).

This strategy was selected by the model when an ER threshold of 40 or 45 incremental colonoscopies per LYG was applied.

Class‐specific efficient frontiers for strategies other than colonoscopy were created, including only those strategies with the same start age and stop age as the benchmark colonoscopy strategy (Table 2). Per screening class, 1 screening strategy was in or near the efficient frontier, had an ER smaller than the benchmark colonoscopy strategy, and had at least 90% of the LYG from the benchmark strategy, thereby fulfilling the criteria to be recommended by the model. In addition to colonoscopy screening every 10 years, our model recommended FIT screening annually, SIG every 5 years, and CTC every 5 years from ages 45 to 75 years (Table 2).

With an ER threshold of 50, screening was recommended from ages 40 to 75 years by colonoscopy every 10 years, FIT every year, SIG every 5 years, and CTC every 5 years (Supporting Table 5). Irrespective of the ER threshold, no HSgFOBT and FIT‐DNA strategies were recommended. HSgFOBT strategies were not on the efficient frontier and for the few efficient FIT‐DNA strategies that were, the ER was higher than the colonoscopy benchmark.

Sensitivity Analyses

As shown in Table 3, alternative assumptions that were explored in the sensitivity analyses influenced the model recommendations. First, when the increased CRC incidence was incorporated as faster adenoma progression to malignancy rather than higher adenoma onset, the model suggested to start screening at age 40 years for all ER thresholds. Second, if the assumed higher CRC incidence was confined to ages <50 years, colonoscopy screening every 10 years from ages 50 to 75 years resulted in the lowest ER: 40.7. The model recommended starting screening at age 40 years by colonoscopy every 10 years with ER thresholds of 45 and 50. Finally, model‐recommended strategies depended on the level of increase in CRC incidence. The start age for colonoscopy decreased as IRRs increased. With an ER threshold of 45, the optimal age to start screening remained at age 50 years for IRRs < 1.3, whereas the optimal age to start screening was decreased to age 40 years with an IRR of ≥1.7. The first and second alternative assumption did not influence the stopping age nor the screening interval, but stopping age and/or interval were influenced by some of the more extreme IRRs.

Table 3.

Model‐Recommended Colonoscopy Strategies Under Alternative Model Assumptions Evaluated in the Sensitivity Analyses

| Recommended Colonoscopy Strategies, Start Age/End Age/Interval. Years | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | ER < 40 | ER < 45 | ER < 50 |

| Base casea | 45/75/10 | 45/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| Faster adenoma progression | 40/75/10 | 40/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| Higher incidence only < 50 y | 50/75/10b | 40/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| Different IRR | |||

| 1.2 | 50/75/10 | 50/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| 1.3 | 50/75/10 | 45/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| 1.4 | 45/75/10 | 45/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| 1.5 | 45/75/10 | 45/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| 1.6 | 45/75/10 | 45/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| 1.7 | 45/75/10 | 40/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| 1.8 | 45/75/10 | 40/75/10 | 40/75/10 |

| 1.9 | 45/75/10 | 40/75/10 | 40/80/10 |

| 2.0 | 40/75/10 | 40/80/10 | 45/75/5 |

| 2.1 | 40/75/10 | 45/75/5 | 40/75/5 |

| 2.2 | 40/80/10 | 45/75/5 | 40/75/5 |

| 2.3 | 40/80/10 | 40/75/5 | 40/75/5 |

| 2.4 | 45/75/5 | 40/75/5 | 40/75/5 |

Abbreviations: ER, efficiency ratio; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Colonoscopy strategies are described by age at which to start screening/age to stop screening/screening interval. ER thresholds of 40, 45, and 50 colonoscopies per life‐year gained were evaluated.

In our base case analyses, we assumed an IRR of 1.591 and we assumed that the higher incidence was caused by an increase in adenoma onset instead of faster adenoma progression. Furthermore, we assumed that the current generation of 40‐year‐old individuals will carry forward escalated disease risk as they age.

50/75/10 had an ER of 40.7; it was the strategy with the lowest ER among the strategies that met the life‐year gained criterion.

DISCUSSION

The results of the current analyses suggest that screening initiation at age 45 years has a favorable balance between screening benefits and burden based on the increase in CRC incidence in young adults. For current 40‐year‐olds, the model recommends screening every 10 years with colonoscopy, every year with FIT, every 5 years with SIG, or every 5 years with CTC from ages 45 to 75 years. The model‐recommended start age depended on the ER threshold that was applied; when 50 colonoscopies per LYG was used as a threshold, the model recommended starting screening at age 40 years.

The results of the current study were sensitive for alternative assumptions regarding the magnitude and etiology of the increase in CRC incidence in young adults; however, the model recommended starting screening before age 50 years, often even at age 40 years, in the majority of alternative scenarios. Thus, the model recommendation of screening initiation at age 45 years appears robust and may even be conservative. Close monitoring of the developments in CRC incidence is required to inform future guidelines because incidence is increasing with each subsequent birth cohort.6

To our knowledge, the current study is the first study that incorporates the recent increase in CRC incidence, especially for rectal and distal colon cancer, in a decision‐analytic modeling approach to assess CRC screening. Our estimated benefits of screening, which resulted in decreased incremental burden‐to‐benefit ratios, were much higher compared with the analysis performed to inform the USPSTF guidelines.14 For example, the LYG and ERs for screening every 10 years by colonoscopy from ages 50 to 75 years were 248 and 39 for the USPSTF analysis, versus 404 and 23 in this analysis. In addition, in contrast to the analysis performed for the USPSTF, SIG screening every 5 years was recommended by the model. This likely can be attributed to the higher percentage of tumors in the rectum and the distal colon. The only other difference between the current model and the one used for USPSTF was the update of the lifetable from 2009 to 2012, which did not meaningfully influence findings (data not shown).

The ER of colonoscopy screening every 10 years from ages 45 to 75 years in our analysis was 32, a lower ratio of incremental burden to benefit than the ER of the model‐recommended colonoscopy strategy in the USPSTF analysis. In contrast to the USPSTF analysis, this analysis to inform the ACS was only performed by 1 of the 3 CISNET models. However, the other 2 CISNET models already suggested that starting screening at age 45 years was preferred in the analysis for the USPSTF, in which the higher risk was not incorporated, albeit with a 15‐year interval for colonoscopy screening.14

Decision models are a useful tool with which to inform screening guidelines because they can extrapolate evidence and predict long‐term outcomes of numerous screening strategies. Decision modeling is an important component within the context of all scientific evidence that is taken into consideration when screening guidelines are evaluated. Since the USPSTF recommendations, compelling empirical data from Siegel et al6 have demonstrated that the increase in CRC incidence is primarily the result of a strong birth cohort effect, which fueled debate regarding the age of screening initiation. This debate triggered reanalysis of the optimal age to begin and end screening and the screening interval that CISNET models performed earlier for the USPSTF. Taken together, empirical data and modeling now suggest that screening should be started at an earlier age for those at average risk of disease. Our model recommendation to start screening at age 45 years instead of age 50 years is driven solely by the assumed increase in CRC disease burden. A study by Murphy et al suggested that the increase in CRC incidence in younger ages is likely caused by an increase in colonoscopy use rather than an increase in disease burden, based in part on stable CRC mortality rates.24 It is important to note that Murphy et al presented mortality data from 1992 through 2013 and did not systematically quantify recent trends. Race‐specific examination of CRC mortality from 1970 to 2014 among individuals aged 20 to 49 years by Siegel et al demonstrated that although CRC mortality is decreasing in blacks, it actually is increasing in whites. Moreover, the trend is consistent with a cohort effect, with the increase beginning in 1995 for individuals aged 30 to 39 years and in 2005 for individuals aged 40 to 49 years, a decade later than the uptick in incidence for each age group.25 Therefore, because the increase in incidence is accompanied by an increase in mortality, higher colonoscopy use in individuals aged <50 years does not appear to be the main driver of the increase in CRC incidence in young adults.

The current study has several limitations. First, it is not known whether the increase in CRC incidence is caused by an increase in the number of adenomas, a faster adenoma progression to malignancy, or some combination of the 2. We found that under both assumption of a higher adenoma onset as well as faster adenoma progression, screening initiation before age 50 years was optimal and therefore also would be expected for the combination of assumptions. Future research is needed to determine the cause and carcinogenic pathway of the increase in CRC. Second, it is not certain that the current 40‐year‐olds will carry forward the same escalated disease risk as they age. Therefore, we evaluated the extreme, namely that they would return to levels for 1975‐1979 levels, in a sensitivity analysis. Although this impacted the predicted benefits of screening, this only further lowered the recommended starting age to 40 years when an ER threshold of 45 incremental colonoscopies per LYG was applied. Third, we used the number of LYG and the number of colonoscopies to measure the benefits and the burden, respectively. Therefore, the burden of tests other than colonoscopies was not considered, which made direct comparison of all strategies not possible. Fourth, to the best of our knowledge, there is no commonly accepted threshold for the incremental number of colonoscopies per LYG. For the USPSTF analysis, 39 was considered an acceptable ratio for our model.14 Because it is recommended to evaluate multiple willingness‐to‐pay thresholds,22 we evaluated ER thresholds of 40, 45, and 50. Although these thresholds are subjective and do influence our model recommendations, the ER for screening initiation at age 45 years was 32 in this analysis, and therefore was superior to the ER accepted by the USPSTF.14 Fifth, similar to the assumptions in our analysis for the USPSTF,14 we assumed perfect adherence to all screening, diagnostic follow‐up, and surveillance tests for the purpose of comparing the performance of individual tests under ideal assumptions. Therefore, the model predicted the maximum achievable benefit for all screening strategies. In reality, the current percentage of being up to date with screening is 61.1%,26 and the adherence to diagnostic follow‐up and surveillance is approximately 80%.27, 28 This suggests that the model‐predicted benefits will not be achieved. However, guidelines are optimally based on the full potential of benefit that would accrue under complete adherence to recommendations because assuming realistic adherence might result in recommending more frequent screenings as the model then compensates for the substantial percentage of the population that does not participate in every recommended screening. For individuals who do adhere to the recommendations, this actually would result in overscreening associated with unnecessary burden. Furthermore, public health organizations will always seek to increase adherence to recommendations. Sixth, the lack of empirical data regarding the performance of CRC screening tests in adults aged 45 to 49 years means that we assumed that these tests would perform equally well in this age group compared with adults aged 50 to 54 years. In fact, apart from a lower prevalence of disease, there is little reason to expect that performance would differ. In the case of visual tests, lesions of interest should have similar visibility. Tests for occult blood have been shown to perform differently by age, but the difference in characteristics is small at younger ages. Harms associated with colonoscopy should be lower given the observation that harms increase with increasing age. Finally, we did not tailor recommendations to population characteristics, whereas further personalization of screening may improve the balance of burden to benefit. In the accompanying article, Meester et al have demonstrated that when incidence is updated in race‐ and sex‐specific analyses, screening is recommended from age 45 years for all race and gender combinations.29

A well‐established decision‐analytic modeling approach that incorporates the increase in CRC incidence among those of younger ages suggests that screening from ages 45 to 75 years is recommended for the current generation of 40‐year‐olds. Colonoscopy screening every 10 years, annual FIT screening, SIG screening every 5 years, and CTC screening every 5 years are screening strategies with similar benefits and acceptable colonoscopy burdens. If the gradual increase in CRC incidence in more recent birth cohorts continues, even earlier start ages for screening should be considered in the future.

FUNDING SUPPORT

Supported by the American Cancer Society (ACS). The development of the Microsimulation Screening Analysis‐Colon was supported by grant U01‐CA199335 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as part of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) and by grant P30‐CA008748. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the ACS and the NCI. The ACS receives partial funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to support the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, of which Dr. Robert A. Smith is the co‐chair, to support initiatives related to colorectal cancer screening outside of the current study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Rebecca L. Siegel is employed by the American Cancer Society, which received a grant from Merck Inc for intramural research outside of the current study. However, her salary is solely funded through American Cancer Society funds. Dennis J. Ahnen has received honoraria for acting as a scientific advisor for Cancer Prevention Therapeutics and as a member of the Speakers Bureau for Ambry Genetics for work performed outside of the current study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Elisabeth F.P. Peterse: Formal analysis, investigation, data curation, methodology, software, visualization, and writing–original draft. Reinier G.S. Meester: Formal analysis, validation, methodology, software, visualization, and writing–original draft. Rebecca L. Siegel: Data curation and methodology. Jennifer C. Chen: Data curation and project administration. Andrea Dwyer: Conceptualization. Dennis J. Ahnen: Conceptualization. Robert A. Smith: Conceptualization and supervision. Ann G. Zauber: Conceptualization, supervision, and methodology. Iris Lansdorp‐Vogelaar: Supervision, methodology, software, and writing–original draft.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

Supporting Information 1

See companion article on pages http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.31542/full, this issue.

We thank Amy B. Knudsen, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston for sharing scripts that were used to generate the efficient frontier figures and Douglas A. Corley, MD, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Division of Research in San Francisco for fruitful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1. American Cancer Society . Cancer statistics center. https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/?_ga=1.33682849.1877282425.1465291457#/cancer-site/Colorectum. Accessed April 30, 2018.

- 2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:177‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holme O, Bretthauer M, Fretheim A, Odgaard‐Jensen J, Hoff G. Flexible sigmoidoscopy versus faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD009259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bibbins‐Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;315:2564‐2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al; American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group; US Multi‐Society Task Force; American College of Radiology Colon Cancer Committee . Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi‐Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:130‐160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974‐2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Austin H, Henley SJ, King J, Richardson LC, Eheman C. Changes in colorectal cancer incidence rates in young and older adults in the United States: what does it tell us about screening. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:191‐201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Connell JB, Maggard MA, Liu JH, Etzioni DA, Livingston EH, Ko CY. Rates of colon and rectal cancers are increasing in young adults. Am Surg. 2003;69:866‐872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age‐related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975‐2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:17‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siegel RL, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increase in incidence of colorectal cancer among young men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1695‐1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Singh KE, Taylor TH, Pan CG, Stamos MJ, Zell JA. Colorectal cancer incidence among young adults in California. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2014;3:176‐184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. North American Association of Central Cancer Registries . NAACCR Incidence Data‐CiNA Analytic File, 1995‐2014, Public Use (which includes data from CDC's National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR), CCCR's Provincial and Territorial Registries, and the NCI's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Registries), certified by the NAACCR as meeting high‐quality incidence data standards for the specified time periods, submitted December 2016.

- 13. National Center for Health Statistics . US Vital Statistics System. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:2595‐2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Hees F, Habbema JD, Meester RG, Lansdorp‐Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG. Should colorectal cancer screening be considered in elderly persons without previous screening? A cost‐effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:750‐759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lansdorp‐Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, Habbema JD, Kuipers EJ. Effect of rising chemotherapy costs on the cost savings of colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1412‐1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Mariotto AB, et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:849‐857, W152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gatto NM, Frucht H, Sundararajan V, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Risk of perforation after colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy: a population‐based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:230‐236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program . SEER*Stat Software, version 8.3.4. Surveillance Research Program. http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/. Accessed August 24, 2017.

- 20. Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi‐Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844‐857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mark DH. Visualizing cost‐effectiveness analysis. JAMA. 2002;287:2428‐2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost‐effectiveness analyses: Second Panel on Cost‐Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 2016;316:1093‐1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Atreja A, Bellam N, Levy SR. Strategies to enhance patient adherence: making it simple. MedGenMed. 2005;7:4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murphy CC, Lund JL, Sandler RS. Young‐onset colorectal cancer: earlier diagnoses or increasing disease burden? Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1809‐1812.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer mortality rates in adults aged 20 to 54 years in the United States, 1970‐2014. JAMA. 2017;318:572‐574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2015 National Health Interview Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm. Accessed September 27 2017.

- 27. Colquhoun P, Chen HC, Kim JI, et al. High compliance rates observed for follow up colonoscopy post polypectomy are achievable outside of clinical trials: efficacy of polypectomy is not reduced by low compliance for follow up. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:158‐161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long‐term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1106‐1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meester RGS, Peterse EFP, Knudsen AB, et al. optimizing colorectal cancer screening by race and sex: microsimulation analysis II to inform the American Cancer Society colorectal cancer screening guideline. Cancer. 2018;124:2974‐2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

Supporting Information 1