Abstract

Liver fibrosis is characterized by the activation and migration of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) followed by matrix deposition. Recently, several studies have shown the importance of extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from liver cells, such as hepatocytes and endothelial cells, in liver pathobiology. While most of the studies describe how liver cells modulate HSC behavior, an important gap exists in the understanding of HSC-derived signals and more specifically HSC-derived EVs in liver fibrosis. Here, we investigated the molecules released through HSC-derived EVs, the mechanism of their release and the role of these EVs in fibrosis. Mass spectrometry analysis showed that platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor α (PDGFRα) was enriched in EVs derived from PDGF-BB-treated HSCs. Moreover, patients with liver fibrosis had increased PDGFRα levels in serum EVs compared to healthy individuals. Mechanistically, in vitro tyrosine720-to-phenylalanine mutation (Y720F) on PDGFRα sequence abolished enrichment of PDGFRα in EVs and redirected the receptor towards degradation. Congruently, the inhibition of Src homology 2 domain tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2), the regulatory binding partner of phosphorylated Y720, also inhibited PDGFRα enrichment in EVs. EVs derived from PDGFRα-overexpressing cells promoted in vitro HSC migration and in vivo liver fibrosis. Finally, administration of SHP2 inhibitor, SHP099, to carbon tetrachloride-administered mice inhibited PDGFRα enrichment in serum EVs and reduced liver fibrosis. Conclusion: PDGFRα is enriched in EVs derived from PDGF-BB-treated HSCs in an SHP2-dependent manner and these PDGFRα-enriched EVs participate in development of liver fibrosis.

Keywords: receptor tyrosine kinase secretion, post-translational modifications, hepatic pericyte, cell migration, fibrogenesis

Despite the great potential of the liver to regenerate, some injurious stimuli, such as chronic alcohol exposure or hepatitis C virus infection, can lead to liver fibrosis followed by liver cirrhosis (1). Cirrhosis is a significant cause of mortality representing 2% of worldwide total deaths in 2010 (2). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop effective therapies. The development of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and, in particular, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor (PDGFR) inhibitors, for the treatment of liver fibrosis represents an active area of investigation (3). Thus, a better understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms regulating liver fibrosis may facilitate the identification of novel therapeutic strategies.

Liver fibrosis is characterized by the activation, migration and proliferation of quiescent liver pericytes, called hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), with subsequent fibrogenesis. Key pathways that contribute to liver fibrosis are PDGF-BB, transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), vascular endothelial growth factor, connective tissue growth factor and reactive oxygen species secreted by several cell types, such as hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, endothelial cells, pro-fibrotic macrophages, biliary epithelial cells and platelets (4–7). PDGF-BB binds to PDGFRs and induces receptor autophosphorylation on specific tyrosine residues (8). While PDGFRβ is well-studied, less is known about PDGFRα (1). Ligand binding to PDGFRα induces phosphorylation of several tyrosines such as Y572, Y574 (9) or Y720 (10). Molecules such as Src homology 2 domain tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2), can bind to these specific phosphorylated tyrosines of the receptor for downstream signaling activation, leading to HSC proliferation and migration (1). Interestingly, Hayes et al. reported that in vivo genetic deletion of PDGFRα reduced liver fibrosis (11). Nevertheless, there exists a lack of studies regarding PDGFRα mechanism and role in liver fibrosis.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been shown to play an important role in liver diseases (12–14). EVs are cell-derived nano-sized vesicles secreted in the extracellular milieu. They can originate from cell membrane budding or from multivesicular body content release (13). In liver, our group and others have demonstrated that cellular stress enhances hepatocyte EV secretion and modifies EV cargo (12, 15–18). Lipotoxicity-induced EV release from hepatocytes recruits pro-inflammatory macrophages (12), which secrete cytokines and chemokines such as PDGFs and TGFβ inducing HSC activation (7). Furthermore, sphingosine kinase 1-enriched EVs derived from sinusoidal endothelial cells induce HSC migration in a sphingosine 1 phosphate-dependent manner (19). While most of the studies describe how liver cells modulate HSC behavior, an important gap exists in the understanding of HSC-derived signals and more specifically HSC-derived EVs in liver fibrosis.

In this study, we demonstrate that PDGFRα-enriched HSC-derived EVs promoted liver fibrosis. This enrichment was due to the specific phosphorylation of tyrosine 720 (Y720) in the intracellular kinase domain of the receptor. Phosphorylated Y720 recruited SHP2, which accompanied PDGFRα to the EVs. PDGFRα-enriched EVs induced in vitro HSC migration by triggering downstream motility signaling in the recipient cells. In vivo transplantation of PDGFRα-enriched EVs promoted liver fibrosis. Finally, in vivo inhibition of SHP2 blocked PDGFRα-enrichment in serum EVs and liver fibrosis. These results suggest that the targeting of PDGFRα in HSC-derived EVs is a novel mechanism to regulate PDGFRα cellular levels upon ligand binding and to promote liver fibrosis.

Experimental procedures

EV purification

EVs were purified from cell conditioned media, mouse or human serum by differential ultracentrifugation (20): 10 min at 300g, 30 min at 20000g (20k fraction) and 2.5 hours at 110000g (110k fraction) using OptimaXPN-80 ultracentrifuge. EVs were resuspended at the same volume for Nanoparticle-Tracking Analysis (NTA, NS300) or western blot (WB) analysis.

In vivo experiments

Six-week old wild-type (WT) C57Bl/6 male and female mice (Envigo) underwent bile duct ligation (BDL) to induce liver fibrosis, as previously described (21) and kept 3 weeks. In a second model of liver fibrosis, CCl4 (1µL/g, Sigma-Aldrich #319961) was administered twice a week for 4 weeks. SHP099 (MedChemExpress, HY-100388) was dissolved in 5%DMSO and administered daily at 5mg/kg for 4weeks. For EV transplant, unlabeled or PKH76-labeled PDGFRα-overexpressing LX2-derived EVs were used; 2×109 EVs/mouse/day (22) were administered daily for 3–4 weeks. Serum and livers were analyzed by Sirius red, Masson’s trichrome and WB. Serum EVs derived from olive oil-, CCl4- or CCl4+SHP099-treated mice were administrated daily at 100µg of EVs/mouse/day to WT mice for 10 days. CCl4, SHP099 and EVs were administered intraperitoneally.

Patient samples

Patient serum samples were obtained and analyzed under Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board-approved protocols. Patient demographics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients with or without liver fibrosis.

| Age | Gender | Category | Sample | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 55 | M | Cirrhotic liver | Serum | Heavy drinker |

| 38 | M | Cirrhotic liver | Serum | Heavy drinker |

| 54 | F | Cirrhotic liver | Serum | Heavy drinker |

| 21 | M | Healthy liver | Serum | Heavy drinker |

| 47 | F | Cirrhotic liver | Serum | Heavy drinker |

| 53 | F | Healthy liver | Serum | Heavy drinker |

| 29 | M | Cirrhotic liver | Serum | Heavy drinker |

| 61 | M | Healthy liver | Serum | Heavy drinker |

| 50 | M | Healthy liver | Serum | Heavy drinker |

| 55 | M | Healthy liver | Serum | Hemangioma |

| 51 | M | Healthy liver | Serum | Hemangioma |

| 64 | F | Healthy liver | Serum | Hemangioma |

| 57 | F | Healthy liver | Serum | Hemangioma |

| 52 | M | Fibrotic liver | Serum | PSC |

| 61 | M | Fibrotic liver | Serum | PSC |

| 62 | F | Fibrotic liver | Serum | PSC |

| 58 | F | Fibrotic liver | Serum | PSC |

Statistical analysis

All experiments were done at least in triplicates, from three independent experiments. The data were analyzed using ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test and t-tests. For in vitro results, paired t-test was used. The difference was considered significant when p<0.05. The results are presented as mean±SEM.

Supplementary methods describe cell culture, EV imaging, mass spectrometry, western blotting, primary antibodies, gene expression, siRNA knockdown, site directed mutagenesis, mutagenesis primers, wound-healing assay, phospho-kinase assay and immunofluorescence.

Results

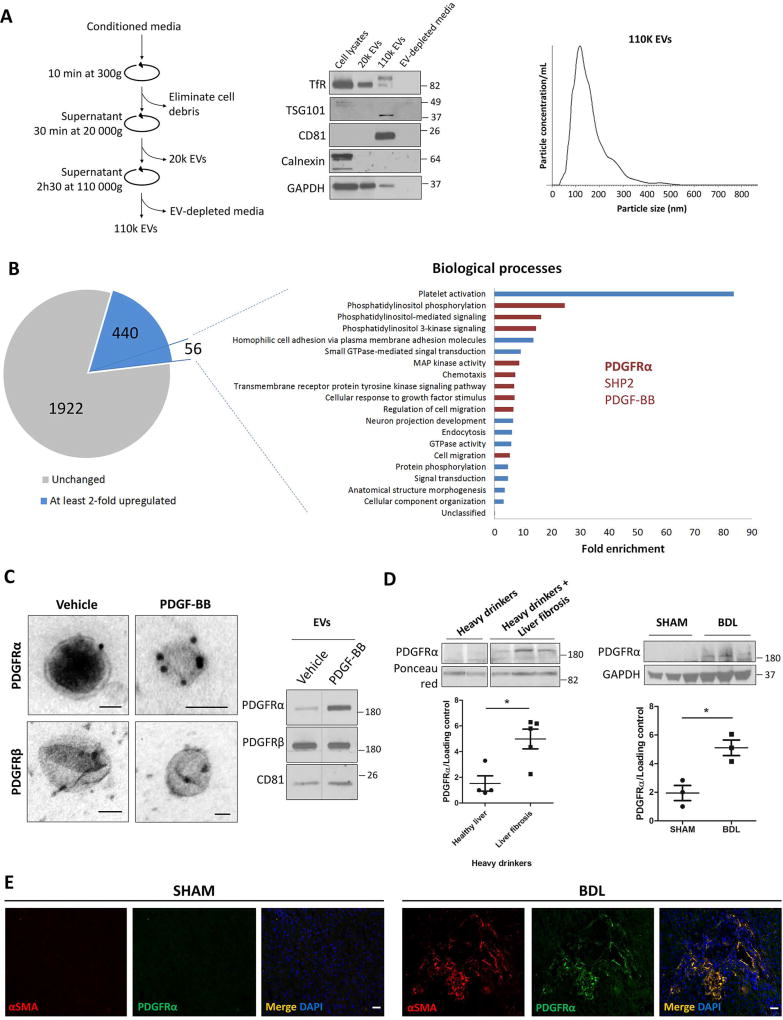

PDGFRα is enriched in HSC-derived EVs

As a first step for our study, we collected primary human HSC-derived EVs by differential ultracentrifugation (Figure 1A, left). WB showed that the 110k EVs expressed high levels of tumor susceptibility gene 101 and cluster differentiation 81, which are reported to be enriched in exosomes compared to microvesicles (23), but not transferrin receptor, when compared to whole cell lysate and the 20k pellet. Moreover, 110k EVs were negative for the endoplasmic reticulum molecule calnexin, confirming the purity of these EVs and the absence of cell debris (Figure 1A, middle). NTA showed that 110k EV mode size was approximately 110 nm (Figure 1A, right). Due to a size overlap between exosomes and microvesicles, the 110k fraction might contain some subsets of smaller microvesicles as well as exosomes. Next, HSCs were treated with vehicle, TGFβ or PDGF-BB for 12 hours to induce HSC activation. Compared to vehicle, PDGF-BB, but not TGFβ, treatment increased EV release by more than 50% with no significant change in EV size as assessed by NTA (Supp.Figure 1A). This increase in EV release was confirmed by WB when loading the same volume of media for each condition (Supp.Figure 1B).

Figure 1. PDGFRα is enriched in HSC-derived EVs.

A. The differential ultracentrifugation method was used for EV purification (left). HSC whole cell lysate, HSC-derived EVs (20k and 110k) and the EV-depleted media were analyzed by WB (middle). The 110k EVs was analyzed by NTA (right).

B. Mass spectrometry on EVs derived from 12-hour treated HSCs with vehicle or PDGF-BB. Out of 2364 detected proteins, 440 were at least 2-fold upregulated. A filter of at least 10 weighted spectrum counts per protein and at least 80% of exclusivity were applied on the 440 molecules, giving a total number of 56 proteins. Gene ontology analysis of the 56 proteins showed their implication in several biological processes (p<0.05). In red are the processes implicated in cell migration. PDGFRα, its binding partner SHP2 and its ligand PDGF-BB were common to these processes.

C. EVs derived from HSCs treated for12 hours with vehicle or PDGF-BB were analyzed by TEM coupled to immunogold staining (left) and by WB (right). Scale bars: 50 nm.

D. EVs derived from patient (left) and mouse (right) sera were analyzed by WB. The number of patients and mice is represented by the dots in the scatter plots.

E. PDGFRα/αSMA double immunostaining on SHAM (left) or BDL (right) mouse livers. Scale bars: 20 µm.

The loading controls are indicated and the molecular weights are expressed in kDa, TSG101: tumor susceptibility gene 101, TfR: transferrin receptor, CD81: cluster of differentiation 81, *: p<0.05.

To examine the effect of PDGF-BB on the protein cargo released through HSC-derived EVs, we performed an unbiased mass spectrometry-based analysis using the same number of EVs per condition. A total of 2364 proteins were detected (Supp.Table 1), 440 of which were at least 2-fold upregulated in the PDGF-BB condition (Figure 1B, pie chart). A filter of at least 10 weighted spectrum counts per protein and at least 80% of exclusivity (Supp.Table 1) brought the number of proteins to 56 (Figure 1B, pie chart). These 56 upregulated proteins were examined using Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis to identify biological processes where they are implicated (Figure 1B, Biological processes histogram). The p-value of all the enriched biological processes was lower than 0.05. Many of these processes are implicated in cell migration (in red, Figure 1B, histogram), which is one of liver fibrosis features. PDGFRα, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) involved in cell migration, was common to these processes and was enriched under PDGF-BB condition; PDGFRβ showed no difference between the conditions (Supp.Table 1). At the mRNA level, PDGFRα did not show enrichment in EVs (Supp.Figure 2A–B), suggesting that the enrichment is not due to increased transcription but by packaging the protein into the EVs. Additionally, TGFβ treatment did not affect PDGFRα enrichment in EVs (Supp.Table 1). PDGFRα enrichment after PDGF-BB, but not TGFβ or PDGF-AA, treatment was confirmed by immunogold-coupled transmission electron microscopy and WB (Figure 1C, Supp.Figures 1B, 2C–E). Furthermore, PDGFRα was enriched in serum EVs from alcoholic liver disease (ALD) patients and from mice after chronic liver injury induced by BDL (Figure 1D). In BDL mouse liver, PDGFRα is mainly expressed by alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA)+cells (Figure 1E), suggesting that PDGFRα-enriched EVs from the liver derive principally from activated HSCs. However, PDGFRα enrichment was not observed in primary sclerosis cholangitis patient sera when compared to control (Supp.Figure 2F), suggesting that the mechanism of PDGFRα-targeting to EVs might be different in primary sclerosis cholangitis patients compared to ALD patients. Taken together, these results demonstrate that HSCs release PDGFRα-enriched EVs. Moreover, ALD patients and mice with liver fibrosis show an increase in PDGFRα enrichment in their serum EVs.

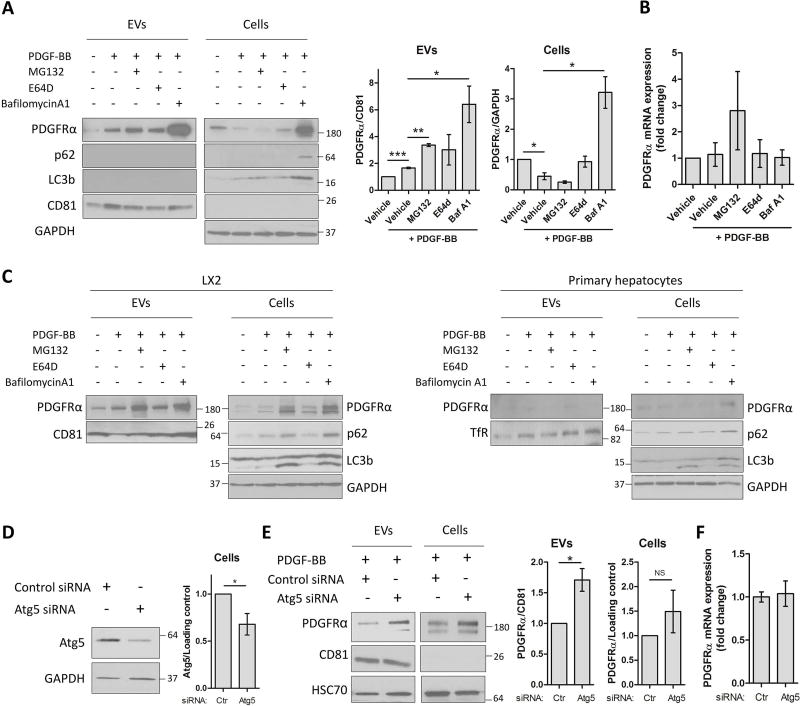

Inhibition of degradation leads to enhanced PDGFRα enrichment in EVs

PDGFRα is an RTK that upon ligand binding is internalized into the endosomes and degraded (24–26). Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that PDGFRα can also be released through EVs. Therefore, we sought to investigate whether impaired degradation affects PDGFRα enrichment in EVs. One hour prior to PDGF-BB addition, HSCs were pre-treated with MG132, E64d or BafilomycinA1 to block proteasome, lysosome or autophagic degradation, respectively. MG132 and BafilomycinA1, but not E64d, induced PDGFRα enrichment in EVs. MG132 enhanced PDGFRα enrichment by 2-fold compared to PDGF-BB condition, but significantly reduced PDGFRα cellular levels (Figure 2A). BafilomycinA1 induced a significant 3-fold increase of PDGFRα enrichment in EVs and a massive accumulation of PDGFRα in cell lysates when compared to PDGF-BB only (Figure 2A), which suggests a decrease of PDGFRα degradation. None of the treatments significantly affected PDGFRα mRNA levels (Figure 2B). Microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta (LC3b) and sequestosome-1 (p62) upregulation after BafilomycinA1 treatment also suggested a role for autophagic degradation in PDGFRα release through EVs. Similar results were obtained when treating PDGFRα-expressing LX2 cells (HSC line), but not when treating primary human hepatocytes, where degradation inhibition did not induce PDGFRα enrichment in hepatocytes-derived EVs indicating HSC selectivity for this effect (Figure 2C). To confirm that inhibition of PDGFRα degradation enriches the receptor in the EVs, we blocked autophagy by silencing autophagy related 5 (Atg5), one of the autophagosome components. Atg5 knock-down was confirmed by WB (Figure 2D). Atg5 siRNA transfection followed by 12-hour PDGF-BB treatment induced a significant increase of PDGFRα enrichment in EVs (Figure 2E) without affecting PDGFRα gene expression (Figure 2F), similarly to BafilomycinA1. In summary, these results demonstrate that degradation inhibition enhances PDGFRα release through EVs.

Figure 2. Inhibition of degradation leads to enhanced PDGFRα enrichment in HSC-derived EVs.

A. HSCs were treated with MG132, E64d or Bafilomycin A1 for 1 hour. PDGF-BB was added and cells were cultured for 12 additional hours. Whole cell lysates and EVs were examined by WB. PDGFRα levels were quantified by densitometry (graphs on the right, n=3).

B. PDGFRα gene expression was quantified by qPCR (n=3).

C. PDGFRα transfected LX2 cells and primary hepatocytes were treated with MG132, E64d or Bafilomycin A1 for 1 hour. PDGF-BB was added and cells were culture for 12 additional hours. Whole cell lysates and EVs were examined by WB (n=3).

D. HSCs were transfected with Atg5 siRNA and 3 days later Atg5 knockdown efficiency was examined by WB in cells and quantified by densitometry.

E. Two days after Atg5 siRNA transfection, HSCs were cultured with PDGF-BB for 12 hours. Whole cell lysates and EVs were analyzed by WB and quantified by densitometry.

F. PDGFRα mRNA expression was analyzed by qPCR (n=4).

The loading controls are indicated and the molecular weights are expressed in kDa. NS: not significant, TfR: transferrin receptor, CD81: cluster of differentiation 81, *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001.

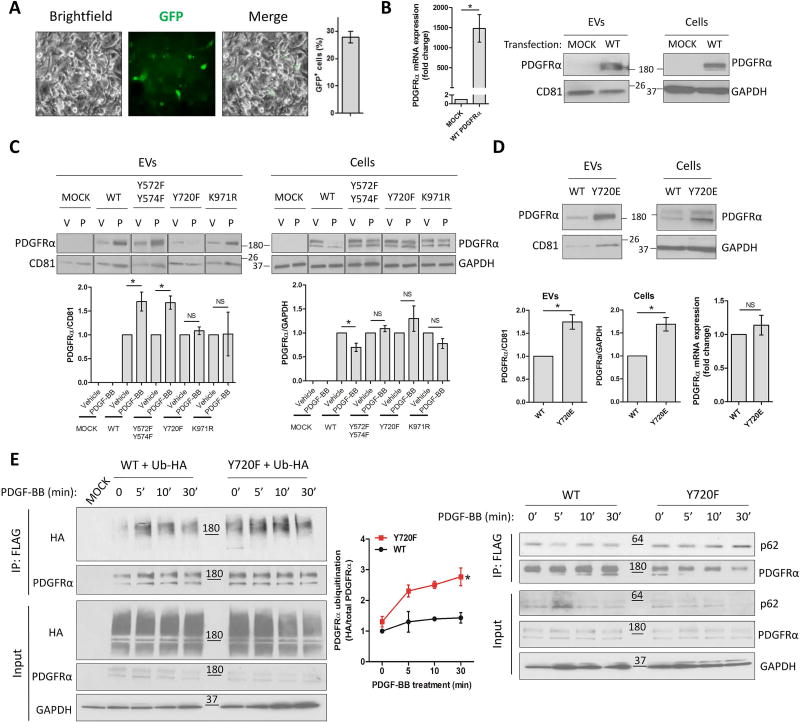

Tyrosine 720 phosphorylation is essential for PDGFRα release through EVs

Tyrosine phosphorylation and lysine ubiquitination on receptor tyrosine kinases are essential for downstream signaling, and for receptor internalization and degradation (24–27). Based on our results, we next sought to explore post-translational modifications that specifically drive PDGFRα enrichment in EVs. For this purpose, ubiquitin and phospho-mutants were generated from a WT PDGFRα-FLAG plasmid containing a GFP reporter gene. Based on canonically important residues of PDGFRα from the literature (9, 10, 28, 29), we generated lysine971-to-arginine (K971R), tyrosines572/574-to-phenylalanines (YY572/574FF) and Y720F mutants (Supp.Figure 3). We specifically used LX2 cells for those studies, which express only low levels of endogenous PDGFRα. LX2 were first transfected with WT PDGFRα plasmid and the overexpression was measured by GFP expression (Figure 3A), by PDGFRα mRNA levels (Figure 3B, left) and by WB in cells and EVs (Figure 3B, right). Next, LX2 were mock-transfected or transfected with WT or mutated PDGFRα. All mutants impaired PDGFRα downregulation in cell lysates after PDGF-BB treatment. However, only Y720F mutant consistently abolished PDGFRα enrichment in EVs (Figure 3C). As a control, WT or Y720F PDGFRα-transfected LX2 were treated with vehicle, TGFβ or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Neither TGFβ nor LPS induced WT or Y720F PDGFRα enrichment in EVs (Supp.Figure 4A), suggesting that phosphorylated Y720-dependent PDGFRα targeting to EVs is selectively induced by PDGF-BB. To confirm the importance of Y720 phosphorylation in PDGFRα release through EVs, we generated a constitutively active phospho-mimetic Y720-to-glutamate (Y720E) mutation construct. LX2 were transfected with WT or Y720E PDGFRα and cultured in basal condition. WT and Y720E PDGFRα were overexpressed at the same level (Figure 3D, bottom right). Y720E construct induced PDGFRα enrichment in EVs, similarly to PDGF-BB effect, and accumulation in cell lysate (Figure 3D). We next sought to investigate whether impairment of Y720 phosphorylation enhances PDGFRα degradation by examining PDGFRα ubiquitination levels. LX2 were co-transfected with ubiquitin-HA plasmid and with WT or Y720F PDGFRα plasmid. Cells were then treated for 0, 5, 10 or 30 minutes with PDGF-BB. PDGFRα was immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG antibody and ubiquitin levels of the receptor were assessed using anti-HA antibody. At all time-points, Y720F mutant showed at least 2-fold more ubiquitination than the WT PDGFRα (Figure 3E, left). Nevertheless, ubiquitination has been reported to be important both for degradation (30, 31) and for EV release (32). Since p62 is implicated in protein degradation, we examined co-immunoprecipitation of p62 with PDGFRα. Indeed, p62-Y720F mutant association was enhanced compared to WT PDGFRα (Figure 3E, right), suggesting a higher degradation for the receptor with impaired Y720 phosphorylation. Taken together, these results suggest that Y720 phosphorylation is crucial for PDGFRα enrichment in EVs by preventing PDGFRα degradation. Furthermore, these data provide an association between degradation and secretion: impairment of degradation enhances PDGFRα release through EVs and inhibition of PDGFRα enrichment in EVs induces its association to degradation molecules.

Figure 3. Tyrosine 720 phosphorylation promotes PDGFRα enrichment in EVs.

A. LX2 cells were transfected with WT PDGFRα-FLAG plasmid containing the GFP reporter gene. GFP expressing cells were quantified 2 days later.

B. PDGFRα overexpression was measured by qPCR in cells and by WB in EVs and cells.

C. LX2 cells were transfected with WT or phospho-mutant PDGFRα plasmids. Two days later, cells were treated with vehicle (V) or PDGF-BB (P) for 12 hours. Whole cell lysates and EVs were analyzed by WB (n=4).

D. LX2 cells were transfected with WT or phospho-mimetic PDGFRα plasmids. Two days later, cells were cultured in basal conditions for 12 hours. Whole cell lysates and EVs were analyzed by WB and PDGFRα mRNA expression in cells was assessed by qPCR (n=4).

E. LX2 cells were transfected with ubiquitin-HA plasmid and with WT or Y720F PDGFRα-FLAG plasmid. Two days later, cells were treated with PDGF-BB as indicated. PDGFRα was immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody. Ubiquitin was detected using an anti-HA antibody (left). Co-immunoprecipitation with p62 was also assessed by WB (right) (n=3).

The loading controls are indicated and the molecular weights are expressed in kDa. NS: not significant, CD81: cluster of differentiation 81, *: p<0.05.

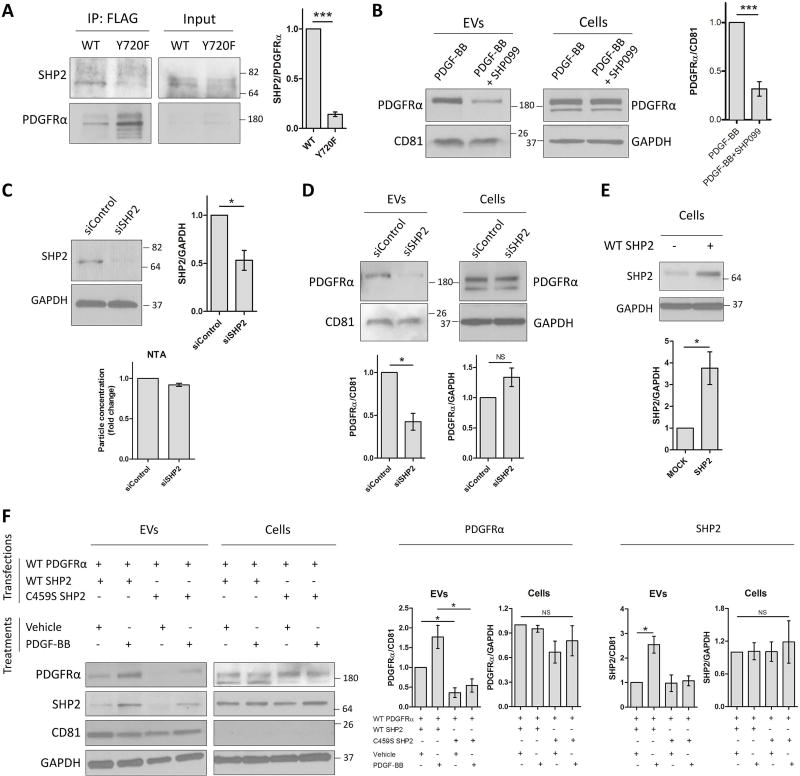

SHP2 activity is essential for PDGFRα EV sorting

SHP2 binds specifically to the phosphorylated Y720 of PDGFRα (10, 33) and is essential for downstream signaling (34). Thus, we sought to investigate the role of SHP2 in PDGFRα enrichment in EVs. We examined the binding of SHP2 to WT and Y720F PDGFRα. SHP2 binding to Y720F was decreased compared to WT PDGFRα (Figure 4A). We then inhibited SHP2 activity by pre-treating human primary HSCs with an SHP2 selective inhibitor (SHP099) prior to LPS, TGFβ or PDGF-BB addition. Inhibition of SHP2 activity did not induce changes in cellular PDGFRα levels, but significantly decreased PDGFRα enrichment in EVs under PDGF-BB condition (Figure 4B). However, SHP099 did not block PDGFRα enrichment in EVs under TGFβ or LPS stimulation (Supp.Figure 4B). Next, we performed SHP2 silencing using siRNA transfection. SHP2 knockdown was confirmed by WB (Figure 4C, top), had no effect on the secreted EV number (Figure 4C, NTA histogram) and did not change the cellular levels of PDGFRα. However, SHP2 silencing significantly reduced PDGFRα targeting to EVs (Figure 4D), similar to SHP099. To further confirm the importance of SHP2, we sought to investigate the role of its catalytic activity in PDGFRα enrichment in EVs using exogenous WT and a cysteine459-to-serine (C459S) mutant SHP2 (35). SHP2 overexpression was confirmed using WB assay (Figure 4E). Congruent with the previous results, the impaired catalytic function (C459S SHP2 mutant) significantly abolished PDGFRα enrichment in EVs, in vehicle and PDGF-BB conditions, without affecting PDGFRα cellular levels (Figure 4F). Moreover, and in line with mass spectrometry screening results, SHP2 was also enriched in EVs derived from PDGF-BB–treated HSCs. This enrichment was abolished when the catalytic domain of SHP2 was impaired (C459S SHP2 mutant, Figure 4F). PDGFRα phosphorylation and SHP2 are important for extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2) activation and downstream signaling (25, 34). Thus, we examined Erk1/2 phosphorylation induced by Y720F mutant and after SHP2 inhibition. Y720F mutant decreased Erk1/2 activation upon PDGF-BB treatment (Supp.Figure 4C). In line with this, SHP2 inhibition using SHP099 compound and C459S SHP2 mutant abolished Erk1/2 phosphorylation (Supp.Figure 4D–E). Finally, Erk1/2 inhibitor SCH772984 decreased PDGF-BB-induced PDGFRα enrichment in EVs and in cell lysates (Supp.Figure 4F). In summary, these data demonstrate that upon PDGF-BB, but not LPS or TGFβ, treatment SHP2 binds to phosphorylated Y720 and SHP2 phosphatase activity induces PDGFRα and SHP2 enrichment in EVs. Moreover, Erk1/2 activation is also important for PDGFRα enrichment in EVs, demonstrating the crucial role of downstream signaling molecules in RTK trafficking through EVs.

Figure 4. SHP2 activation promotes PDGFRα enrichment in HSC-derived EVs.

A. LX2 cells were transfected with WT or with Y720F PDGFRα-FLAG plasmid for 2 days and then treated with PDGF-BB for 30 minutes. PDGFRα was immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody. Co-immunoprecipitation of SHP2 was assessed by WB (n=3).

B. Primary human HSCs were treated with SHP099 for 1 hour. PDGF-BB was added and cells were cultured for 12 additional hours. Whole cell lysates and EVs were examined by WB (n=6).

C. HSCs were transfected with SHP2 siRNA and 3 days later SHP2 knockdown efficiency in cells was examined by WB (n=3).

D. Two days after SHP2 siRNA transfection, HSCs were cultured with PDGF-BB for 12 hours. Whole cell lysates and EVs were analyzed by WB (n=4).

E. LX2 cells were transfected with WT SHP2 construct and 2 days later the overexpression was examined by WB (n=4).

F. LX2 cells were co-transfected with WT PDGFRα and WT or C459S SHP2 constructs for 2 days. Cells were then treated with vehicle or PDGF-BB for 12 additional hours. Whole cell lysates and EVs were analyzed by WB (n=3).

The loading controls are indicated and the molecular weights are expressed in kDa. NS: not significant, CD81: cluster of differentiation 81, *: p<0.05, ***: p<0.001.

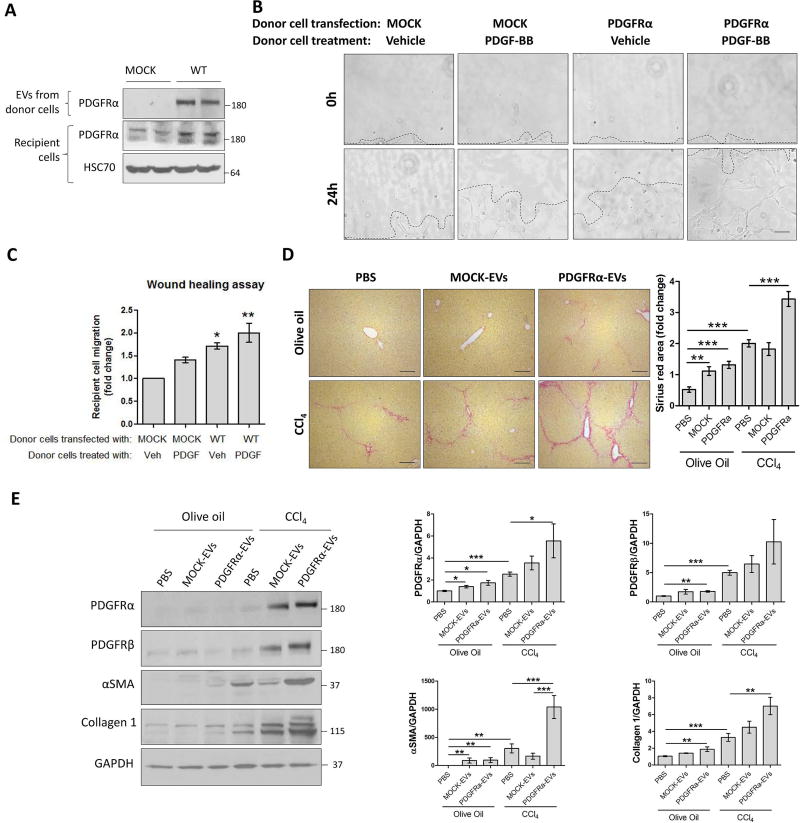

PDGFRα-enriched EVs promote HSC migration

PDGFRα is implicated in cell migration (1), thus we tested whether PDGFRα enrichment in EVs induces HSC migration. LX2 overexpressing PDGFRα and LX2-derived EVs were utilized. To examine EV uptake, we incubated LX2 recipient cells with 2×109 EVs derived from MOCK or WT PDGFRα-transfected LX2 donor cells for 3 hours. Recipient cells showed higher levels of PDGFRα when incubated with PDGFRα-overexpressing EVs than MOCK-EVs (Figure 5A). Next, we performed a wound-healing assay to examine the role of PDGFRα-enriched EVs on LX2 migration. Recipient cells were incubated for 24 hours with EVs derived from either MOCK or WT PDGFRα-transfected cells, each treated with either vehicle or PDGF-BB. PDGFRα-EVs induced a greater migration of the recipient cells when compared to MOCK-EVs (Figure 5B–C). When either MOCK or PDGFRα-transfected donor cells were treated with PDGF-BB, EVs induced an even greater migration (Figure 5B–C). These results were confirmed by using primary human HSCs and HSC-derived EVs; EVs derived from PDGF-BB-treated HSCs induced greater migration than EVs derived from vehicle-treated HSCs (Supp.Figure 5A). Furthermore, recipient cell migration was reduced when EVs derived from SHP099-treated PDGFRα-overexpressing donor cells (Supp.Figure 5B). Despite the effect on migration, there was no stimulatory effect on αSMA, collagen1 or fibronectin mRNA levels in recipient cells when EVs were enriched for PDGFRα (Supp.Figure 6A). The effect of these EVs was also examined on liver macrophages and their canonical functions such as TNFα and IL1β mRNA induction. PDGFRα-enriched EVs did not increase TNFα or IL1β mRNA levels in Kupffer cells (Supp.Figure 6B), suggesting that their effect might be selective to HSC migration. To examine how the transfer of PDGFRα through EVs triggers migration in recipient cells, a phospho-kinase protein array was performed on these EVs. Indeed, PDGFRα-overexpressing EVs had higher levels of pro-migration proteins such as phospho-focal adhesion kinase and phospho-protein kinase B 1/2/3 (Supp.Figure 7A–C). TGFβ did not induce an increase of PDGFRα signaling in the EVs (Supp.Figure 7D). In summary, these results demonstrate that PDGF-BB-dependent PDGFRα-enriched EVs principally promote HSC migration likely by transferring activated downstream signaling molecules, critical for these processes.

Figure 5. PDGFRα-enriched EVs promote cell migration and liver fibrosis.

A. Donor LX2 cells were transfected with WT PDGFRα construct for 2 days. EVs derived from these cells were incubated with non-transfected LX2 cells for 3 hours. The overexpression of PDGFRα in donor cells and PDGFRα levels in recipient cells were examined by WB.

B. Confluent LX2 cells were scratched using a 10 µL pipette tip. Cells were washed and incubated with donor cell EVs in basal media for 24 hours. The migration of cells in 3 selected area was measured at 0 and 24 hours (n=3).

C. Quantification of cell migration.

D and E. C57Bl/6 male and female mice were treated for 4 weeks with PBS, mock or PDGFRα overexpressing EVs in parallel with olive oil or CCl4 injections. Livers were analyzed by Sirius red (D) and WB (E). (5–9 animals/group).

The loading controls are indicated and the molecular weights are expressed in kDa. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001, scale bars: 50 µm.

PDGFRα-enriched EVs promote liver fibrosis

Based on the in vitro results and since HSC migration contributes to liver fibrosis in vivo, we next sought to examine the effect of PDGFRα-enriched EVs in liver fibrosis. For this purpose, uptake of injected EVs to the liver was first assessed. PDGFRα-FLAG-EVs were labeled with a green fluorescent membrane dye PKH67 and injected via tail vein. Mice were sacrificed 5 hours later. Compared to saline-injected mice, EV-injected mice showed great numbers of fluorescent green puncta in their livers (Supp.Figure 8A). FLAG immunostaining confirmed the presence of EVs in the liver after intravenous as well as intraperitoneal injection (Supp.Figure 8B). Based on the above, 2×109 EVs, derived from MOCK- or PDGFRα-transfected LX2, were transplanted daily via intraperitoneal injections in olive oil or CCl4-treated mice for 4 weeks. Interestingly, PDGFRα-EVs induced Sirius red staining significant increase in olive oil and CCl4 groups (Figure 5D). Moreover, PDGFRα-EV transplant significantly enhanced levels of pro-fibrotic proteins PDGFRα, PDGFRβ, αSMA and collagen1 in whole liver lysates, as shown by the quantification of WB bands (Figure 5E). The in vivo pro-fibrogenic role of PDGFRα-enriched EVs was confirmed in a BDL-induced fibrosis model. PDGFRα-EVs, but not MOCK-EVs, significantly enhanced BDL-induced liver fibrosis, as demonstrated by Sirius red staining and protein levels of collagen1 and αSMA (Supp.Figure 9). In summary, these results demonstrate that PDGFRα-enriched EVs potentiate liver fibrosis in vivo in response to injury.

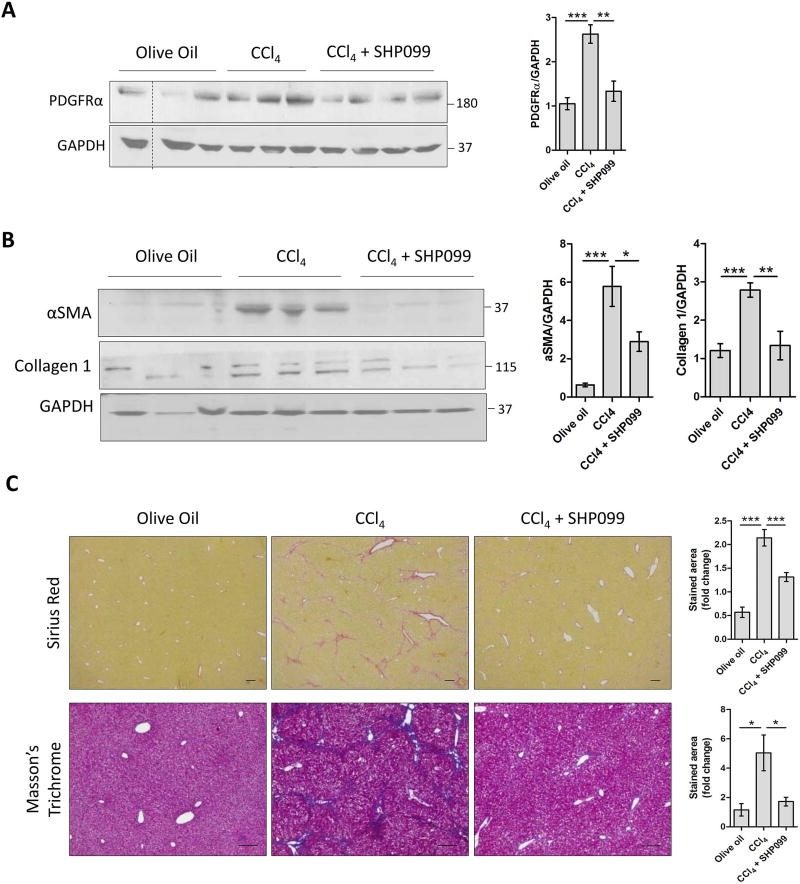

SHP2 inhibition reduces PDGFRα release through EVs and prevents liver fibrosis in vivo

As PDGFRα-enriched EVs are pro-fibrogenic, we hypothesized that inhibition of PDGFRα release through EVs may reduce liver fibrosis. Based on the in vitro effect of SHP2 inhibition on PDGFRα enrichment in EVs, we examined the in vivo effect of SHP099 on PDGFRα release through EVs. Mice were treated with olive oil, CCl4 or CCl4+SHP099 for 4 weeks. As expected, CCl4 induced an increase in PDGFRα enrichment in serum EVs (Figure 6A), similar to the BDL model (Figure 1D). Importantly, SHP099 administration abolished this enrichment (Figure 6A), confirming our in vitro results (Figure 4B). Interestingly, SHP099 also significantly abolished liver fibrosis as shown by αSMA, collagen1 protein levels, Sirius red and Masson’s trichrome staining (Figure 6B–C). These results were also confirmed in a BDL model, where SHP099 reduced Sirius red staining and collagen1 protein levels in whole liver lysates (Supp.Figure 10). To further support the role of SHP2 in PDGFRα enrichment in EVs and liver fibrosis, mice were treated with olive oil, CCl4, CCl4+PDGFRα-EVs or CCl4+PDGFRα-SHP099-EVs. PDGFRα-SHP099-EVs derived from PDGFRα-overexpressing donor cells treated with SHP099. Sirius red staining was higher in CCl4+PDGFRα-EV-injected mice than in CCl4-injected mice. This increase was attenuated when PDGFRα-SHP099-EVs were administered (Supp.Figure 11A–B). This was confirmed by collagen1 and αSMA WB (Supp.Figure 11C). In another experiment, we investigated the role of EVs derived from sera of olive oil-, CCl4- or CCl4+SHP099-treated donor mice on recipient WT mice. Sirius red staining of recipient mouse livers did not display any difference between the three groups (Supp.Figure 11D), suggesting that EVs require a chronic liver injury stimulus such as CCl4 in order to manifest fibrosis. In summary, these results support the role of SHP2 in PDGFRα enrichment in EVs, which drive liver fibrosis.

Figure 6. In-vivo SHP2 inhibition reduces PDGFRα release through serum EVs and prevents liver fibrosis.

C57Bl/6 male and female mice were treated for 4 weeks with olive oil, CCl4 or CCl4+SHP099. Serum EVs (A) and whole liver lysates (B) were analyzed by WB. Liver sections were examined by Sirius red staining and Masson’s trichrome staining (C).

The loading controls are indicated and the molecular weights are expressed in kDa. *: p<0.05, scale bars: 50 µm, 5–10 animals/group.

Discussion

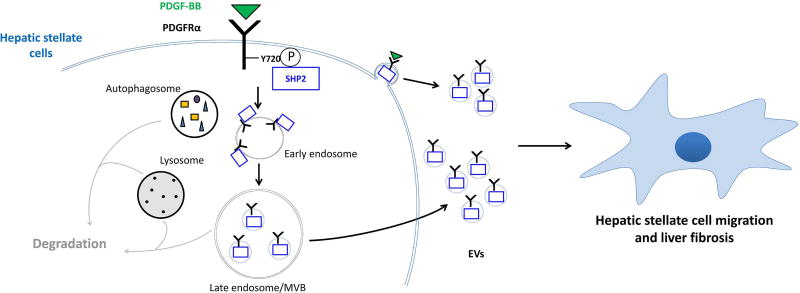

In this study, we unveil a pathway of broad biological relevance involving the targeting of PDGFRα to EVs and their role in liver fibrosis. We demonstrate that PDGFRα enrichment in HSC-derived EVs is a novel mechanism to regulate PDGFRα cellular levels upon ligand binding, in close association with its degradation. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 720 drives PDGFRα targeting to EVs but not to degradation by binding to SHP2, suggesting a new role for this signaling molecule. Furthermore and most importantly, we provide evidence that PDGFRα-enriched EVs trigger in vitro HSC migration and in vivo liver fibrosis, which can be therapeutically targeted by inhibition of SHP2 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Proposed mechanism.

Upon PDGF-BB binding, PDGFRα auto-phosphorylates tyrosine 720 (Y720) in the kinase domain. When phosphorylated, Y720 recruits SHP2, which is essential for PDGFRα enrichment in EVs. Both, PDGFRα and SHP2 are released through EVs (exosomes as well as a subpopulation of small microvesicles), which induce hepatic stellate cell migration and liver fibrosis.

EVs have emerged as an important mechanism for cell-to-cell communication by transporting, among several types of molecules, functional RTKs such as EGFR (13, 36, 37). In liver disease, hepatocyte- or endothelial cell-derived EVs participate in disease progression (18, 19). Nevertheless, little is known about EVs deriving from HSCs, the main mediators of liver fibrosis. In this study, we demonstrate that HSC-derived EVs transport PDGFRα, which is enriched in the EVs upon PDGF-BB stimulation, suggesting a regulation mechanism for its trafficking, in addition to its degradation. Some prior studies show that degradation inhibition by BafilomycinA1 enhances EV release (38, 39). In addition to this, here we demonstrate that degradation inhibition leads to further enrichment of EVs for PDGFRα and, in turn, blockage of PDGFRα enrichment in EVs enhances its degradation. This close relation between degradation and release through EVs suggests a fine-tuned regulation of the bioavailability of PDGFRα in response to ligand stimulation.

It has been reported that PDGFRα can be secreted through oligodendrocyte-derived EVs during development (40). However, the mechanism of PDGFRα release through EVs, and of RTKs in general, remains unknown. Some studies demonstrate that association to RalA and RalB proteins (41) or post-translational modifications such as ISGylation (39) and ubiquitination (32) are essential for general EV secretion. However, ubiquitination is also crucial for cargo degradation. Therefore, the precise mechanism targeting PDGFRα to EVs rather than to degradation and whether ubiquitin is involved in this decision remain unclear. Some prior studies indicate a link between phosphorylation of proteins and their release through EVs (42, 43), but little is known about the balance between phosphorylation and ubiquitination in the fate of RTK trafficking. To understand the role of post-translational modifications in PDGFRα trafficking to EVs, we studied several phospho- and ubiquitination-mutants. Only impaired tyrosine720 phosphorylation (Y720F) abolished PDGFRα enrichment in EVs. Moreover, Y720F mutation enhanced PDGFRα ubiquitination and its association with the autophagic protein p62. These data demonstrate that PDGFRα enrichment in EVs is dependent on Y720 phosphorylation and that impairment of this phosphorylation redirect PDGFRα towards degradation by elevating its ubiquitination levels. This suggests that specific tyrosine residues have distinct roles regarding the fate of the receptor, which can be important for downstream signaling.

The specific partner binding to phosphorylated Y720 is SHP2 (10), which is an essential phosphatase for the activation of downstream signaling of RTKs (35). SHP2 has been reported to promote breast cancer and liver cancer progression by triggering several biological processes such as cell proliferation and migration (44, 45). Interestingly, a recent study emphasizes the role of phosphatases in cellular trafficking and re-routing of RTKs (46). In our study, SHP2 promoted PDGFRα trafficking through EVs. Moreover, our proteomics analysis demonstrated that SHP2 is also enriched in EVs after PDGF-BB stimulation. SHP2 can modulate mitogen-activated protein kinase activity (MAPK) such as Erk1/2 (34, 35). Furthermore, MAPK molecules KRAS-MEK control the sorting of Ago2 protein into EVs (42). Along this line, we show that inhibition of Erk1/2 activation abolishes PDGFRα enrichment in EVs. Taken together, these results demonstrate that SHP2 binding to PDGFRα is essential for enrichment of these two proteins in EVs, which suggest a potential role of these EVs in liver fibrosis.

RTKs, such as EGFR, can be transported through EVs and trigger signaling in recipient cells (36, 47). Moreover, HSC-derived EVs can bind to other HSCs through integrins and heparin sulfate proteoglycans (48). Congruently, we demonstrate that PDGFRα trafficking through HSC-derived EVs promotes in vitro HSC migration. Nevertheless, much less is known on the in vivo role of HSC-derived EVs. In our study, ALD patients and mice with BDL contained higher levels of PDGFRα in their serum EVs compared to respective controls. Moreover, we demonstrate that PDGFRα-enriched EVs induced in vivo liver fibrosis, emphasizing a new mechanism involved in hepatic fibrosis. Finally, in vivo inhibition of PDGFRα release through EVs using a specific SHP2 inhibitor in a CCl4-induced fibrosis model correlated with significant reduction of liver fibrogenesis, providing a potential therapeutic strategy for liver diseases.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates a novel SHP2-dependent mechanism by which PDGFRα enrichment in HSC-derived EVs drives liver fibrosis. Inhibition of PDGFRα enrichment in EVs may be a novel therapeutic strategy against liver diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. David J. Katzmann, Andrius Kazlauskas, Cao Sheng and Tushar Patel, Mayo Clinic Microscopy Core, Proteomics Core, Molecular Biology Core, Animal Facilities and the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology.

Financial support: National Institutes of Health, USA R01 DK59615 and R01 AA21171 (VHS), American Liver Foundation (EK), Edward C. Kendall Research Fellowship (PH), Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (NIDDK P30DK084567) and Mayo Clinic.

Abbreviations

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- EV

extracellular vesicle

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PDGFR

PDGF receptor

- Y720F

tyrosine720-to-phenylalanine

- CCl4

carbon tetrachloride

- SHP2

Src homology 2 domain tyrosine phosphatase 2

- WB

western blot

- NTA

nanoparticle-tracking analysis

- BDL

bile duct ligation

- LC3b

microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta

- p62

sequestosome-1

- Atg5

autophagy related 5

- WT

wild-type

- K971R

lysine971-to-arginine

- Y720E

tyrosine720-to-glutamate

- C459S

cysteine459-to-serine

- Erk1/2

extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2

- αSMA

alpha smooth muscle actin

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- ALD

alcoholic liver diseases

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

References

- 1.Kikuchi A, Monga SP. PDGFRalpha in liver pathophysiology: emerging roles in development, regeneration, fibrosis, and cancer. Gene Expr. 2015;16:109–127. doi: 10.3727/105221615X14181438356210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AA, Lopez AD, Shahraz S, Lozano R, Mokdad AH, Stanaway J, Murray CJ, et al. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12:145. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah VH, Bruix J. Antiangiogenic therapy: not just for cancer anymore? Hepatology. 2009;49:1066–1068. doi: 10.1002/hep.22872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostallari E, Shah VH. Angiocrine signaling in the hepatic sinusoids in health and disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;311:G246–251. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00118.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagy LE. The Role of Innate Immunity in Alcoholic Liver Disease. Alcohol Res. 2015;37:237–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torok NJ. Dysregulation of redox pathways in liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;311:G667–G674. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00050.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuchida T, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. Signal transduction by receptors with tyrosine kinase activity. Cell. 1990;61:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90801-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelderloos JA, Rosenkranz S, Bazenet C, Kazlauskas A. A role for Src in signal relay by the platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5908–5915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazenet CE, Gelderloos JA, Kazlauskas A. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 720 in the platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor is required for binding of Grb2 and SHP-2 but not for activation of Ras or cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6926–6936. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes BJ, Riehle KJ, Shimizu-Albergine M, Bauer RL, Hudkins KL, Johansson F, Yeh MM, et al. Activation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha contributes to liver fibrosis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsova P, Ibrahim SH, Krishnan A, Verma VK, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Charlton MR, et al. Lipid-Induced Signaling Causes Release of Inflammatory Extracellular Vesicles From Hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:956–967. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsova P, Ibrahim SH, Verma VK, Morton LA, Shah VH, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ, et al. Extracellular vesicles in liver pathobiology: Small particles with big impact. Hepatology. 2016;64:2219–2233. doi: 10.1002/hep.28814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato K, Meng F, Glaser S, Alpini G. Exosomes in liver pathology. J Hepatol. 2016;65:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bala S, Petrasek J, Mundkur S, Catalano D, Levin I, Ward J, Alao H, et al. Circulating microRNAs in exosomes indicate hepatocyte injury and inflammation in alcoholic, drug-induced, and inflammatory liver diseases. Hepatology. 2012;56:1946–1957. doi: 10.1002/hep.25873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrahim SH, Hirsova P, Tomita K, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Harrison SA, Goodfellow VS, et al. Mixed lineage kinase 3 mediates release of C-X-C motif ligand 10-bearing chemotactic extracellular vesicles from lipotoxic hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2016;63:731–744. doi: 10.1002/hep.28252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Povero D, Eguchi A, Li H, Johnson CD, Papouchado BG, Wree A, Messer K, et al. Circulating extracellular vesicles with specific proteome and liver microRNAs are potential biomarkers for liver injury in experimental fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verma VK, Li H, Wang R, Hirsova P, Mushref M, Liu Y, Cao S, et al. Alcohol stimulates macrophage activation through caspase-dependent hepatocyte derived release of CD40L containing extracellular vesicles. J Hepatol. 2016;64:651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang R, Ding Q, Yaqoob U, de Assuncao TM, Verma VK, Hirsova P, Cao S, et al. Exosome Adherence and Internalization by Hepatic Stellate Cells Triggers Sphingosine 1-Phosphate-dependent Migration. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:30684–30696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.671735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thery C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, Clayton A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2006;Chapter 3(Unit 3):22. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0322s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maiers JL, Kostallari E, Mushref M, deAssuncao TM, Li H, Jalan-Sakrikar N, Huebert RC, et al. The unfolded protein response mediates fibrogenesis and collagen I secretion through regulating TANGO1 in mice. Hepatology. 2017;65:983–998. doi: 10.1002/hep.28921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haga H, Yan IK, Takahashi K, Matsuda A, Patel T. Extracellular Vesicles from Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Survival from Lethal Hepatic Failure in Mice. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:1262–1272. doi: 10.1002/sctm.16-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kowal J, Arras G, Colombo M, Jouve M, Morath JP, Primdal-Bengtson B, Dingli F, et al. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E968–977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haglund K, Sigismund S, Polo S, Szymkiewicz I, Di Fiore PP, Dikic I. Multiple monoubiquitination of RTKs is sufficient for their endocytosis and degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:461–466. doi: 10.1038/ncb983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tallquist M, Kazlauskas A. PDGF signaling in cells and mice. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiley HS, Burke PM. Regulation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by endocytic trafficking. Traffic. 2001;2:12–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.020103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mori S, Tanaka K, Omura S, Saito Y. Degradation process of ligand-stimulated platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor involves ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29447–29452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen KT, Lin JD, Liou MJ, Weng HF, Chang CA, Chan EC. An aberrant autocrine activation of the platelet-derived growth factor alpha-receptor in follicular and papillary thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2006;231:192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner SA, Beli P, Weinert BT, Scholz C, Kelstrup CD, Young C, Nielsen ML, et al. Proteomic analyses reveal divergent ubiquitylation site patterns in murine tissues. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:1578–1585. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.017905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baixauli F, Lopez-Otin C, Mittelbrunn M. Exosomes and autophagy: coordinated mechanisms for the maintenance of cellular fitness. Front Immunol. 2014;5:403. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piper RC, Katzmann DJ. Biogenesis and function of multivesicular bodies. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:519–547. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith VL, Jackson L, Schorey JS. Ubiquitination as a Mechanism To Transport Soluble Mycobacterial and Eukaryotic Proteins to Exosomes. J Immunol. 2015;195:2722–2730. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng H, Liu KW, Guo P, Zhang P, Cheng T, McNiven MA, Johnson GR, et al. Dynamin 2 mediates PDGFRalpha-SHP-2-promoted glioblastoma growth and invasion. Oncogene. 2012;31:2691–2702. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Chen YN, LaMarche MJ, Chan HM, Fekkes P, Garcia-Fortanet J, Acker MG, Antonakos B, et al. Allosteric inhibition of SHP2 phosphatase inhibits cancers driven by receptor tyrosine kinases. Nature. 2016;535:148–152. doi: 10.1038/nature18621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tajan M, de Rocca Serra A, Valet P, Edouard T, Yart A. SHP2 sails from physiology to pathology. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58:509–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higginbotham JN, Zhang Q, Jeppesen DK, Scott AM, Manning HC, Ochieng J, Franklin JL, et al. Identification and characterization of EGF receptor in individual exosomes by fluorescence-activated vesicle sorting. J Extracell Vesicles. 2016;5:29254. doi: 10.3402/jev.v5.29254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.S ELA, Mager I, Breakefield XO, Wood MJ. Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:347–357. doi: 10.1038/nrd3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edgar JR, Manna PT, Nishimura S, Banting G, Robinson MS. Tetherin is an exosomal tether. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.17180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Villarroya-Beltri C, Baixauli F, Mittelbrunn M, Fernandez-Delgado I, Torralba D, Moreno-Gonzalo O, Baldanta S, et al. ISGylation controls exosome secretion by promoting lysosomal degradation of MVB proteins. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13588. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pituch KC, Moyano AL, Lopez-Rosas A, Marottoli FM, Li G, Hu C, van Breemen R, et al. Dysfunction of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRalpha) represses the production of oligodendrocytes from arylsulfatase A-deficient multipotential neural precursor cells. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:7040–7053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.636498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hyenne V, Apaydin A, Rodriguez D, Spiegelhalter C, Hoff-Yoessle S, Diem M, Tak S, et al. RAL-1 controls multivesicular body biogenesis and exosome secretion. J Cell Biol. 2015;211:27–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201504136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenzie AJ, Hoshino D, Hong NH, Cha DJ, Franklin JL, Coffey RJ, Patton JG, et al. KRAS-MEK Signaling Controls Ago2 Sorting into Exosomes. Cell Rep. 2016;15:978–987. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuccato E, Blott EJ, Holt O, Sigismund S, Shaw M, Bossi G, Griffiths GM. Sorting of Fas ligand to secretory lysosomes is regulated by mono-ubiquitylation and phosphorylation. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:191–199. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aceto N, Sausgruber N, Brinkhaus H, Gaidatzis D, Martiny-Baron G, Mazzarol G, Confalonieri S, et al. Tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 promotes breast cancer progression and maintains tumor-initiating cells via activation of key transcription factors and a positive feedback signaling loop. Nat Med. 2012;18:529–537. doi: 10.1038/nm.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han T, Xiang DM, Sun W, Liu N, Sun HL, Wen W, Shen WF, et al. PTPN11/Shp2 overexpression enhances liver cancer progression and predicts poor prognosis of patients. J Hepatol. 2015;63:651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baumdick M, Bruggemann Y, Schmick M, Xouri G, Sabet O, Davis L, Chin JW, et al. EGF-dependent re-routing of vesicular recycling switches spontaneous phosphorylation suppression to EGFR signaling. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song X, Ding Y, Liu G, Yang X, Zhao R, Zhang Y, Zhao X, et al. Cancer Cell-derived Exosomes Induce Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase-dependent Monocyte Survival by Transport of Functional Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:8453–8464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.716316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen L, Brigstock DR. Integrins and heparan sulfate proteoglycans on hepatic stellate cells (HSC) are novel receptors for HSC-derived exosomes. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:4263–4274. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.