Abstract

Objective

To evaluate changes in pain (at the knee and elsewhere) and pain sensitization in obese persons with knee pain undergoing bariatric surgery compared with similarly obese persons undergoing medical management.

Methods

Individuals undergoing bariatric surgery and medical management were recruited. Knee pain severity of the more painful knee (index knee) was assessed at baseline and 12 months using the WOMAC. Pressure pain threshold (PPT) was assessed at the index patella and the right wrist. Low patella PPT may reflect peripheral and/or central sensitization and low wrist PPT may reflect central sensitization Mean change in measures of pain and pain sensitization was assessed in the surgery and medical management groups separately.

Results

45 individuals in the surgery group and 22 in the medical management group completed baseline and follow-up visits. The mean weight loss was 32.7 kilograms (29.0%) and 4.6 kilograms (4.1%) in the surgery and medical management groups, respectively. Knee pain decreased in the surgery group only. PPT at the patella improved by 38.5% and the PPT at the wrist improved by 30.9% (p-value=0.0007 and 0.005, respectively) in the surgery group. There was no significant change in PPT in the medical management group.

Conclusions

Persons who underwent bariatric surgery experienced an improvement in pain sensitization, reflected by improvements in PPT. This improvement was not only at the patella, but also at the wrist, suggesting that central sensitization improved after bariatric surgery.

Weight loss from bariatric surgery alleviates many illnesses, including type-2 diabetes and hypertension (1-3). Knee pain also improves (2, 4, 5) but the reason for this improvement is not well understood. Obese individuals have more musculoskeletal pain than those who are not obese, and this is not just because they have more arthritis in affected joints. They may experience more pain due to excess loading across weight bearing joints, and adipose tissue-related generation of adipokines causing low-grade inflammation within joints.

Persistent inflammation and/or mechanical tissue injury, both of which may be present in obesity, can lead to alterations in nervous system nociceptive processing in animal models (6, 7). One such alteration is an increased responsiveness of the peripheral and central nervous systems to nociceptive input (i.e., peripheral and central sensitization). Peripheral and/or central sensitization can result in heightened pain severity, as has been observed in persons with knee osteoarthritis, low back pain and other chronic musculoskeletal disorders (8-10).

It is not clear if pain relief after weight loss is solely related to decreased mechanical loading, which would only affect knee pain, or rather if it is related to improvements in peripheral and/or central sensitization, which may have effects beyond the knee. Our objective was to evaluate changes in pain (at the knee and elsewhere) and pain sensitization in obese persons with knee pain undergoing bariatric surgery compared with similarly obese persons undergoing medical management.

Methods

Subjects were recruited from the Nutrition and Weight Management Center at Boston Medical Center. Both surgery and medical management groups had to meet the body mass index (BMI) eligibility criteria for bariatric surgery of ≥ 35 kg/m2 with a weight-related comorbidity or BMI of ≥ 40 kg/m2 to be included. Subjects had to have knee pain on most days of the past month and be 25-60 years old. Those with prior knee surgery or inflammatory arthritis were excluded. The Boston University Medical Campus institutional review board approved the protocol and all participants provided written informed consent.

Subjects undergoing surgery had either laparoscopic roux-en-y-gastric bypass or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. The medical management group received dietary and exercise prescriptions with or without a combination of medications including phentermine, lorcaserin, phentermine/topiramate, bupropion/naltrexone, or liraglutide. The dietary prescription consisted of a high-protein, low-fat diet of 1200-1500 kilocalories/day for women and 1500-1800 kilocalories/day for men. Meal replacements could be used to substitute meals. Both groups were advised to walk at least 30 minutes/day and perform resistance exercise two times/week.

Assessment of Pain and Pain Sensitization

Assessments occurred at baseline, which for those undergoing surgery was up to two weeks prior to their surgery, and 12 months later for all subjects. Follow up assessment were performed blinded to surgery status. Knee pain was assessed using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) (11). Frequent pain, defined as pain, aching or stiffness on most days in the last 30 days, at 19 sites outside the knees (i.e., bilateral shoulders, elbows, wrists, hands, hips, ankles, feet; neck, upper/middle/lower back, buttocks) was assessed using a body homunculus (12).

Pressure pain threshold (PPT), a measure of mechanical pain sensitivity, has been reported to be reliably assessed using a hand-held algometer in obese older adults with knee pain and/or osteoarthritis (10, 13). The algometer was applied at a rate of 0.5 kg/second to the right wrist (i.e., radioulnar joint) as a control site since this joint is not typically affected by osteoarthritis and the center of the index patella (i.e., most painful knee). PPT was defined as the point at which the pressure changes to slight pain (13). The test was repeated three times and averaged at each site. Lower PPT reflects greater pain sensitivity. We regarded low patella PPT to reflect peripheral and/or central sensitization and low wrist PPT to reflect central sensitization (14).

Statistical Analysis

Change in pain and pain sensitization were evaluated with paired t-tests in the two groups separately. The relation of change in weight loss to change in pain and PPT was assessed with Pearson's correlations in the two groups combined. We also determined the correlation between changes in WOMAC pain and wrist/patella PPT.

Results

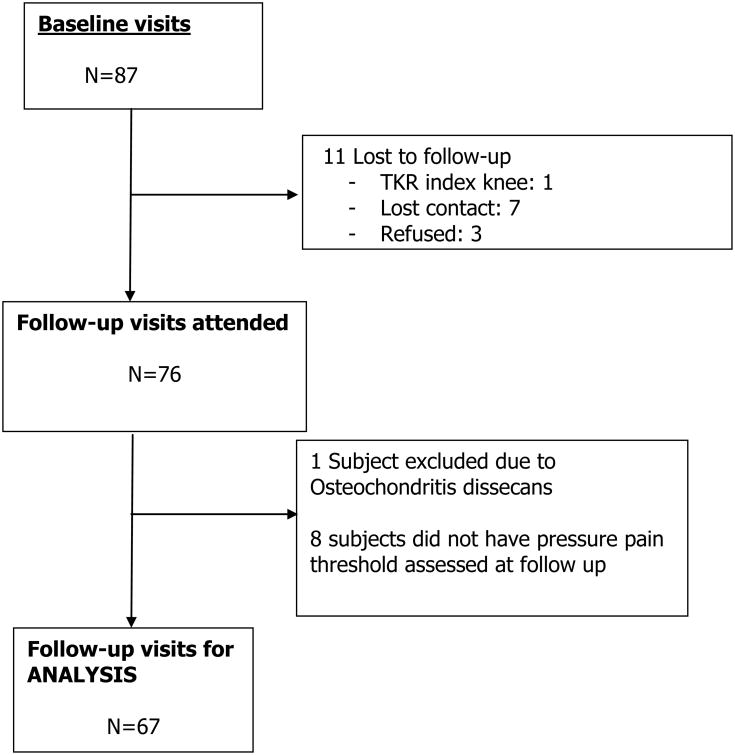

87 individuals completed the baseline visit and 67 (45 individuals in the surgery group and 22 in the medical management group) completed both baseline and follow-up visits (Figure 1). The mean ages were 43.8 years and 48.1 years for the surgery and the medically managed group, respectively. The majority of subjects were female (see Table 1). The baseline mean BMI was 42.1 and 40.7 in the surgery and medical management groups, respectively. Individuals in the surgery group had lower WOMAC scores (less knee pain) and lower patella PPT (more sensitized) than those in the medical management group. The mean (SD) (%) weight loss was 32.7 (11.2) kilograms (29.0%) and 4.6 (9.7) kilograms (4.1%) in the surgery and medical management groups, respectively (Table 2). Baseline demographic and pain measures were not different between those that did and did not complete follow-up visits.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study participants.

Table 1. Baseline statistics*.

| Surgery Group (n=45) | Medical Management Group (n=22) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 43.8 (9.9) | 48.1 (7.1) | 0.07** |

| Female (%) | 97.8% | 86.4% | 0.06*** |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 42.1 (4.2) | 40.7 (5.0) | 0.26** |

| Weight, kg | 113.4 (13.9) | 112.0 (16.6) | 0.72** |

| WOMAC Pain (0-20) | 9.5 (3.4) | 11.5 (4.1) | 0.03** |

| Number of joints with frequent pain (0-21) | 7.1 (3.5) | 6.3 (4.6) | 0.41** |

| PPT Patella, kilopascals | 346.5 (141.2) | 450.7 (217.4) | 0.05** |

| PPT Wrist, kilopascals | 335.6 (133.5) | 387.7 (154.0) | 0.16** |

Values are mean (±SD) unless otherwise noted

Based on t-test

Based on chi-square test

Table 2. Change in weight, pain and sensitization from baseline to follow-up*.

| Surgery Group (n=45) | Medical Management Group (n=22) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Weight (kg) | -4.6 | |

| Baseline | 113.4 | 112.0 |

| Follow-up | 80.7 | 107.5 |

| Change | -32.7 | -4.6 |

| Change (%) | -29.0% | -4.1% |

|

| ||

| WOMAC Pain (0-20) | ||

| Baseline | 9.5 | 11.5 |

| Follow-up | 4.6 | 10.0 |

| Change | -4.9 (p<0.0001) | -1.5 (p=0.13) |

|

| ||

| Number of joints with frequent pain (0-21) | ||

| Baseline | 7.1 | 6.3 |

| Follow-up | 4.8 | 7.1 |

| Change | -2.3 (p=0.002) | +0.9 (p=0.41) |

|

| ||

| PPT Patella | ||

| Baseline | 346.5 | 450.7 |

| Follow-up | 479.8 | 394.4 |

| Change | +133.3 (p=0.0007) | -56.4 (p=0.16) |

|

| ||

| PPT Wrist | ||

| Baseline | 335.6 | 387.7 |

| Follow-up | 439.4 | 432.1 |

| Change | +103.8 (p=0.005) | +44.4 (p=0.23) |

Values are mean unless otherwise noted; p-values are for the within group comparison of baseline and follow-up values

Mean WOMAC scores decreased significantly in the surgery group, whereas changes in the medically managed group were modest and not statistically significant (Table 2). The total number of painful sites also decreased (-2.3; p=0.002) in the surgery group (Table 2). At one year post-surgery, PPT increased by 38.5% at the patella and by 30.9% at the wrist (p-value=0.0007 and 0.005, respectively). There was no significant change in pain or PPT in the medical management group. Change in weight correlated with changes in WOMAC pain (0.50; p<0.0001) and patella PPT (r= -0.33; p=0.006), but not with change in wrist PPT (r= -0.04; p=0.77). Change in WOMAC pain was moderately inversely correlated with change in PPT and the patella (r=-0.4; p=0.007) and wrist (r=-0.4; p=0.002).

Discussion

As noted in previous studies (2, 4, 5), significant weight loss from bariatric surgery reduced knee pain and pain in both weight bearing and non-weight bearing sites outside the knee, but the reason for this improvement has not been well-understood. In this study, WOMAC pain scores improved and PPT at the wrist and patella increased in those undergoing bariatric surgery, whereas no significant changes were seen in a comparable medically managed group. In the presence of sensitization, nociceptors respond to stimuli that they would normally not respond to. However, due to neuroplasticity, removal of the stimuli that contribute to sensitization may normalize nociceptor functioning. Thus, with substantial weight loss, a decrease in obesity-related inflammation (15) and/or mechanical loading may be sufficient to lead to improvements in sensitization. Confirmation of our findings are needed in other cohorts undergoing weight loss. It would be valuable to determine the relation of weight loss to changes in pain sensitization in larger cohorts and those with other rheumatic disorders where bariatric surgery appears to reduce pain (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis).

Improvement in PPT at the wrist suggests that the pain improvement in the surgical subjects was at least in part mediated through central sensitization. Amelioration of sensitization may also explain why there was a generalized decrease in body regions with pain. Thus, we suggest that improvements in pain may be due, at least in part, to improvements in pain sensitization attendant with weight loss. To our knowledge this is the first study that has observed such an improvement.

The lack of correlation between weight loss and change in wrist PPT suggests that a potential mechanism for improved (central) sensitization is likely through other factors, such as decreased inflammatory mediators rather than mechanical unloading, while improvement in (peripheral) sensitization (PPT at the knee) may be related to mechanical unloading. We also recognize that there may be other explanations for improved sensitization after bariatric surgery that we did not assess in our study including but not limited to improved sleep quality, mood, and physical activity. While we saw no change in PPT in the medical management group, whose mean weight loss was 4.1%, many comorbidities of obesity improve with a 5-10% weight loss, and diabetes measures improve with as little as 3% weight loss. Research is needed to ascertain a potential weight loss threshold needed to improve sensitization.

Further insights into the effect of weight loss on changes in pain sensitization would ideally need to consider the role of inflammatory markers in the circulation (e.g., hsCRP, IL-1, IL-6 and TNFα), adipocytokines, or metabolic parameters (e.g., type-2 diabetes) that improve after bariatric surgery. Our study is limited in not having information on these markers. Nonetheless, it would be difficult to tease out the relative contributions of mechanical unloading and inflammation since both influence sensitization. We also recognize that baseline PPT at the patella in the surgery group was lower than the medical management group. This may have affected the amount of change observed in each group. WOMAC pain was also lower in the surgery group. However, this is in an opposite direction than the patella PPT, meaning they had less pain but were more sensitized (lower PPT). It is difficult to know how these differences would influence the results since they had lower pain to begin with. Also, our small sample prohibited analyses to assess confounders and intermediate variables.

In conclusion, improvements in joint pain in those who experience significant weight loss are likely to be due, in part, to improvement in sensitization, including effects on pain beyond reduced loading across painful knee joints.

Significance and Innovations.

Knee pain improves after bariatric surgery, but the mechanism is unknown

Our results demonstrate persons who underwent bariatric surgery experienced an improvement in pain sensitization, evidenced by improvements in pressure pain thresholds

This improvement was not only at the patella, but also at the wrist, suggesting that central sensitization improved after bariatric surgery

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by NIH/NIAMS grant P60-AR47785 (PI: Felson). Dr. Stefanik's work was supported by an Investigator Award from the Rheumatology Research Foundation, a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Arthritis Foundation, and NIH K23 AR070913. Dr. Neogi was supported by NIH/NIAMS R01-AR062506. Dr. Apovian was supported by NIH/NIDDK R01-DK108056. Dr. Apovian reports grants from National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Amylin, personal fees from Nutrisystem, personal fees from Zafgen, personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, grants and personal fees from Orexigen, personal fees from NovoNordisk, grants from Aspire Bariatrics, grants and personal fees from GI Dynamics, grants from Myos, grants and personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Scientific Intake, grants and personal fees from Gelesis, other from Science-Smart LLC, personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Johnson and Johnson, grants from Vela Foundation, and grants from Dr. Robert C. and Veronica Atkins Foundation outside the submitted work. Dr. Neogi's work was supported by NIH R01 AR062506 and K24 AR070892.

References

- 1.Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2416–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooper MM, Stellato TA, Hallowell PT, Seitz BA, Moskowitz RW. Musculoskeletal findings in obese subjects before and after weight loss following bariatric surgery. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(1):114–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugerman HJ, Wolfe LG, Sica DA, Clore JN. Diabetes and hypertension in severe obesity and effects of gastric bypass-induced weight loss. Ann Surg. 2003;237(6):751–6. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000071560.76194.11. discussion 757-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King WC, Chen JY, Belle SH, et al. Change in Pain and Physical Function Following Bariatric Surgery for Severe Obesity. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1362–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards C, Rogers A, Lynch S, et al. The effects of bariatric surgery weight loss on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis. 2012;2012(504189) doi: 10.1155/2012/504189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malfait AM, Schnitzer TJ. Towards a mechanism-based approach to pain management in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(11):654–64. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller RE, Tran PB, Obeidat AM, et al. The Role of Peripheral Nociceptive Neurons in the Pathophysiology of Osteoarthritis Pain. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13(5):318–26. doi: 10.1007/s11914-015-0280-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finan PH, Buenaver LF, Bounds SC, et al. Discordance between pain and radiographic severity in knee osteoarthritis: findings from quantitative sensory testing of central sensitization. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(2):363–72. doi: 10.1002/art.34646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arendt-Nielsen L, Graven-Nielsen T. Central sensitization in fibromyalgia and other musculoskeletal disorders. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2003;7(5):355–61. doi: 10.1007/s11916-003-0034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neogi T, Frey-Law L, Scholz J, et al. Sensitivity and sensitisation in relation to pain severity in knee osteoarthritis: trait or state? Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(4):682–8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felson DT, Niu J, Quinn EK, et al. Multiple Nonspecific Sites of Joint Pain Outside the Knees Develop in Persons With Knee Pain. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(2):335–342. doi: 10.1002/art.39848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wylde V, Palmer S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Test-retest reliability of Quantitative Sensory Testing in knee osteoarthritis and healthy participants. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(6):655–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suokas AK, Walsh DA, McWilliams DF, et al. Quantitative sensory testing in painful osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(10):1075–85. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao SR. Inflammatory markers and bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Res. 2012;61(8):789–807. doi: 10.1007/s00011-012-0473-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]