Abstract

The zinc-regulated transporters, iron-regulated transporter-like proteins (ZIPs), the natural resistance and macrophage proteins (NRAMP), the heavy metal ATPases (HMAs) and the metal tolerance or transporter proteins (MTPs) families are involved in cadmium (Cd) uptake, translocation and sequestration in plants. Mulberry (Morus L.), one of the most ecologically and economically important (as a food plant for silkworm production) genera of perennial trees, exhibits excellent potential for remediating Cd-contaminated soils. However, there is no detailed information about the genes involved in Cd2+ transport in mulberry. In this study, we identified 31 genes based on a genome-wide analysis of the Morus notabilis genome database. According to bioinformatics analysis, the four transporter gene families in Morus were distributed in each group of the phylogenetic tree, and the gene exon/intron structure and protein motif structure were similar among members of the same group. Subcellular localization software predicted that these transporters were mainly distributed in the plasma membrane and the vacuolar membrane, with members of the same group exhibiting similar subcellular locations. Most of the gene promoters contained abiotic stress-related cis-elements. The expression patterns of these genes in different organs were determined, and the patterns identified, allowing the categorization of these genes into four groups. Under low or high-Cd2+ concentrations (30 μM or 100 μM, respectively), the transcriptional regulation of the 31 genes in root, stem and leaf tissues of M. alba seedlings differed with regard to tissue and time of peak expression. Heterologous expression of MaNRAMP1, MaHMA3, MaZIP4, and MaIRT1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae increased the sensitivity of yeast to Cd, suggested that these transporters had Cd transport activity. Subcellular localization experiment showed that the four transporters were localized to the plasma membrane of yeast and tobacco. These results provide the basis for further understanding of the Cd tolerance mechanism in Morus, which can be exploited in Cd phytoremediation.

Keywords: cadmium, Morus, transporter genes, bioinformatics analysis, phytoremediation

Introduction

Due to increasing industrial demands, global cadmium (Cd) extraction from mining increased overall by 19.1% between 2000 and 2016. In 2016, mine production of recoverable Cd was 23000 tons, with China and Korea being the major producers of Cd, with 7400 and 4500 tons of Cd production, respectively (USGS, 2017). Cd is one of the most toxic non-essential elements to organisms. Chronic human exposure to Cd at high concentrations (>30 μg⋅d-1) has the potential to cause kidney damage, bone lesions (itai–itai disease), cancer and lung insufficiency (Figueroa, 2008; Gad, 2014). The main route of human exposure to Cd is through the diet, due to soil Cd pollution (Clemens et al., 2013). A number of Cd-contaminated soil remediation techniques have been researched; compared with many physical and chemical approaches to this problem, phytoremediation is a more environmentally friendly and cost-effective method (Raskin et al., 1997).

In previous studies on phytoremediation, most of them focused on the identification of Cd hyperaccumulator species, such as Arabidopsis halleri, Sedum alfredii, and Noccaea (syn.Thlaspi) caerulescens, the aerial parts of which can accumulate Cd to >100 μg⋅g-1 (Kramer, 2010; Cun et al., 2014). However, most hyperaccumulators are herbaceous plants which have limitations, such as metal selectivity, low biomass, shallow root systems and slow growth rates. Therefore, some fast-growing woody plants have been recommended recently as potential candidates for phytoremediation (Luo et al., 2016). Mulberry exhibit desirable traits such as being highly adaptable, perennial, capable of withstanding pruning, with a high biomass and a widespread distribution (Olson and Fletcher, 2000; Zhao et al., 2013). Mulberry has been shown to be tolerant of Cd, Cr, Pb, Co, and Cu (Ashfaq et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2015a,b). After growing in soil containing 60 μg⋅g-1 Cd for 4 months, the Cd concentration in roots of Morus alba was 95.62 μg⋅g-1 (accumulating Cd to concentrations greater than present in the soil), while in leaves it was 6.48 μg⋅g-1 (Zhou et al., 2015a). Although M. alba is not a Cd hyperaccumulator, it can still accumulate Cd on a large scale because of its large biomass. According to Zhou et al. (2015a), in the presence of increasing Cd concentrations in mulberry leaves, detoxification mechanisms of the silkworm, feeding on its food plant, were activated so that excess Cd was excreted in fecal balls, and the silkworm mortality rate was zero for all treatments. Therefore, the process of Morus growing, silkworm raising, and silk reeling and weaving can also help bring economic benefits to heavy metal- (HM-) contaminated areas, which will increase people’s acceptance of using Morus trees to remediate HM-contaminated soil.

Cd2+ is absorbed from the soil solution by root epidermal cells, and subsequently stored in part in the roots, with the remainder being translocated to the xylem vessels, and sequestered and detoxified in the vacuoles (Mendoza-Cózatl et al., 2011). Thus, uptake, translocation and sequestration of Cd are crucial plant processes for the phytoremediation of Cd-contaminated soil. However, Cd has no known biological function in plants, so there are no specific transporter systems for Cd in plants. Cd2+ is likely to be transported via transporters of essential divalent metal cations (such as Ca2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+) (Shahid et al., 2016). These transporters include the zinc-regulated transporters, iron-regulated transporter-like proteins (ZIP), the natural resistance and macrophage proteins (NRAMP), the heavy metal ATPases (HMA), and the metal tolerance or transporter proteins (MTP) family members, which have been functionally characterized mainly in A. thaliana and Oryza sativa (Luo et al., 2016).

Because of poor selectivity toward divalent metal cations (Fe2+, Mn2+, Cd2+, and Zn2+), NRAMP and ZIP family transporters are mainly responsible for Cd2+ absorption (Mendoza-Cózatl et al., 2011; Shahid et al., 2016). Some studies have reported that N. caerulescens NcZNT1, rice OsIRT1, OsIRT2, OsZIP6, A. thaliana AtIRT1, Medicago truncatula MtZIP6, OsNRAMP1, OsNRAMP5, and Hordeum vulgare NRAMP5 are all localized on the plasma membrane, while mediating Cd2+ uptake in different tissues (Vert et al., 2002; Nakanishi et al., 2006; Stephens et al., 2011; Takahashi et al., 2011; Ishimaru et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016). Meanwhile, there are some members of the NRAMP family, localized to organellar membranes, which also play roles in the distribution of Cd2+ within the cell. AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 are localized to the tonoplast (Thomine et al., 2000; Lanquar et al., 2005), while AtNRAMP6 is targeted to a vesicular-shaped endomembrane compartment (Cailliatte et al., 2009).

Heavy metal ATPases belongs to the large P-type ATPase family, the members of which have been involved in transporting monovalent (Cu+/Ag+) and divalent (Ca2+/Zn2+/Cd2+/Co2+/Pb2+) HM cations. Many members of the latter group have been reported to transport Cd2+. AtHMA3 and OsHMA3 are located in the tonoplast, participating in Cd2+ sequestration to the vacuoles (Morel et al., 2009; Miyadate et al., 2011). Plasma membrane proteins OsHMA2, AtHMA2, and AtHMA4 can load Cd2+ into the xylem, playing a pivotal role in controlling Cd2+ translocation ability from the roots to the shoots of plants (Verret et al., 2004; Jarvis et al., 2009; Wong and Cobbett, 2009; Takahashi et al., 2012). AtHMA1 is localized to the inner envelope membrane of the chloroplast, and has been shown to be able to transport Cd2+ upon heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Seigneurin-Berny et al., 2006; Moreno et al., 2008). MTP belongs to the Cation Diffusion Facilitator (CDF) family (Montanini et al., 2007). Most MTPs are localized to the tonoplast and act as antiporters of Zn2+, Ni2+, and Cd2+, which are involved in sequestration or efflux of these ions to reduce HM toxicity (Ovecka and Takac, 2014). In rice, overexpression of OsMTP1 in yeast and tobacco conferred increased tolerance to Cd2+ (Yuan et al., 2012; Das et al., 2016). In Arabidopsis, AtMTP1 and AtMTP3 are involved in sequestration of excess Zn2+ (Arrivault et al., 2006; Kawachi et al., 2008).

Investigations into these four transporter families in woody plants are limited (Luo et al., 2016). In previous studies, we confirmed that two Morus phytochelatin synthase (PCS) genes conferred Zn/Cd tolerance and accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis and tobacco (Fan et al., 2018). To further understand the mechanisms of Cd-phytoremediation, and to screen for key genes related to Cd uptake, translocation and sequestration in Morus, we identified nine ZIPs, four NRAMPs, 8 HMAs and 10 MTPs (31 genes in total) from M. notabilis. After CdCl2 treatment, expression analysis indicated that the corresponding genes from M. alba displayed various expression patterns, differing between tissues and with respect to the time of peak expression. Moreover, MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4, and MaHMA3 were heterologously expressed in S. cerevisiae to achieve functional characterization.

Materials and Methods

Identification of ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP Genes in Morus

Hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles (PF02535, PF01566, and PF01545) for domains corresponding to ZIP, NRAMP, and MTP gene families were downloaded from Pfam database1. The HMM profile of the HMA gene family was constructed using the hmmbuild feature from the HMMER package 3.1b22 with aligned A. thaliana HMA and O. sativa HMA sequences from TAIR3 and Rice Information Resource4, respectively. The HMM search was performed using hmmsearch (using default e-value of 10) from the HMMER package on the mulberry proteome downloaded from the M. notabilis database5. Then, all Morus ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP genome sequences were directly downloaded from the M. notabilis database according to the Gene-IDs. The downloaded ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP candidate sequences were analyzed manually using the SMART6 and CDD7 databases for the presence of the domains. WoLF PSORT8 and ProtComp 9.09 were used to predict protein subcellular localization. The TMHMM server10 was used to calculate the number of transmembrane helical (TM) domains.

Phylogenetic Analysis, Exon–Intron Structure, Motif Analysis and Promoter Cis-Element Identification

Multiple sequence alignments of the full-length protein sequences were performed using the ClustalX version 2.1 program (Larkin et al., 2007), followed by manual adjustment using the BioEdit version 7.0.9 (Hall, 1999). MEGA version 5.05 (Tamura et al., 2011) was used to determine the substitution model and rate heterogeneity of the best fit with the ZIP, NRAMP, HMA and MTP protein data. Phylogenetic trees were constructed with a maximum likelihood method, using TREE-PUZZLE 5.3. rc16 (Steel, 2010). The number of puzzling steps was set at 10,000. Trees were displayed using online software iTOL11 (Letunic and Bork, 2016). The online software Gene Structure Display server 2.012 (Hu et al., 2015) was used to generate the exon/intron organization of each ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP gene by comparing the cDNA to its corresponding genomic DNA sequence. The Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elucidation (MEME) version 4.11.213 was used to investigate conserved motifs for each ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP gene (Bailey et al., 2009). ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP family sequences from A. thaliana, O. sativa and other species were downloaded from TAIR, Rice Information Resource and the ARAMEMNON plant membrane protein database14, respectively. Promoter sequences, located 1500 bp upstream of the transcription start site, were searched using National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)15, and were analyzed using the PlantCare database16 (Lescot et al., 2002).

Plant Materials and Stress Treatments

Since M. notabilis seedlings only grow in Ya’an, Sichuan, China, at a height of ∼1400 m above sea level, and under ambient conditions such as a mean daytime temperature of ∼22°C, attempts to cultivate this species elsewhere were unsuccessful. M. alba cv. Guiyou No. 62 (Ma-GY62) has been used to study the expression profiles of Morus genes under different stresses (Yang et al., 2015; Cai et al., 2016). Therefore, we used seedlings of Ma-GY62 as the plant material for Cd2+ stress treatments. Ma-GY62 seedlings were planted in soil in a PQX-type plant incubator (Ningbo Southeast Instrument Corporation, Ningbo, China) with a 16 h/8 h light/dark cycle at 26°C/22°C (day/night). After approximately 2 months, the Ma-GY62 seedlings (∼15 cm high) were treated with 0 (control, CK), 30 or 100 μM CdCl2 solution, and the roots, stems, and leaves were sampled at 0, 1, 3, 10, or 24 h after treatment. The corresponding tissues of untreated seedlings were used as controls. All samples were instantly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C.

Assessment of Cd Accumulation in Ma-GY62 Seedlings

To detect the Cd accumulation capacity of Ma-GY62 seedlings grown at the three soil concentrations of Cd (see section “Plant Materials and Stress Treatments”), the root, stem, and leaf tissue of seedlings were separated and immersed in 10 mM ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid for 15 min and washed thoroughly three times with a neutral detergent solution and distilled water. Each sample was dried at 105°C for 30 min, followed by 75°C for 12 h. The dry tissues were ground and suspended in deionized water. The Cd concentrations were determined with atomic absorption spectrophotometry (VARIAN AA 240 Duo, Varian, Palo Alto, CA, United States). Each treatment consisted of three biological replicates.

Cloning and Sequence Identification of Ma-GY62 ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP Genes

Total RNA from the different tissues was extracted using the RNAiso Plus Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA in a 25 μl reaction volume using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa). The gene-specific primers for the 31 genes were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA, United States) (Supplementary Table S1) to amplify the full-length coding sequences (CDS) of the genes from the total cDNA generated from Ma-GY62 leaves. The purified PCR products were TA cloned into the pMD®19-T simple vector (TaKaRa), and then were confirmed by sequencing.

Expression Analysis of the Morus ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP Genes

To further investigate the expression of the 31 genes in different organs, the reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (RPKM) were used to compare differences in gene expression created by the MultiExperiment Viewer (Saeed et al., 2003). The root, branch bark, bud, flower, and leaf RPKM values of M. notabilis ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP genes were retrieved from RNA sequencing data17.

To confirm changes in expression of the 31 genes in response to Cd2+ stress, the gene expression profiles in root, stem, and leaves under different Cd2+ concentration treatments were analyzed by qPCR, with three replicates. The method of qPCR, using SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II (TaKaRa), was as described by Wei et al. (2014). The primer pairs used in the qPCR analysis of the 31 genes were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 (Supplementary Table S1). The MaACTIN3 gene (HQ163775.1) was used as a control to normalize the relative expression of target genes. Relative expression was defined as 2-[Cycle threshold (target gene)-Ct (control gene)].

The data were normalized by log transformation. Cluster analysis was performed by using the pheatmap package version 1.0.818 with Euclidean distance method created by the R package.

Yeast Expression Analysis

The Cd-sensitive ycf1 mutant strain ΔYcf1 (BY4741; MATα; his3Δ1; leu2Δ0; lys2Δ0; ura3Δ0; YDR135c::kanMX4) and the Zn-sensitive zrc mutant strains Δzrc (BY4741; MATa; ura3Δ0; leu2Δ0; his3Δ1; met15Δ0; YMR243c::kanMX4) were grown in YPD or SD-Ura synthetic dropout media. For overexpression of cDNAs of MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4, or MaHMA3, the pYPGE15 yeast expression vector, carrying URA3 as the selectable marker, was used (Cabello-Hurtado and Ramos, 2004). PCR primers, containing restriction enzyme cutting sites, were designed (Supplementary Table S1). After digestion with the corresponding restriction enzyme, they were cloned into pYPGE15.

Transformation of ΔYcf1 and Δzrc strains with the target constructs were performed by electroporation (Becker and Guarente, 1991). For Zn/Cd tolerance testing, single colonies from SD-Ura agar plates were cultured in liquid SD-Ura medium until the optical density (OD600) reached 1.0. Serial dilutions (OD600 = 1, 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001) were spotted onto SD-Ura agar containing various concentrations of either CdCl2 (10 or 20 μM) or ZnSO4 (5 or 10 mM). Plates were photographed after incubation at 30°C for 3 days. Aliquots (100 μl) of the foregoing yeast stains (OD600 = 1.0) were inoculated into 10 ml fresh liquid SD-Ura medium containing various concentrations of CdCl2 (10 or 20 μM) or ZnSO4 (5 or 10 mM). The OD600 values were measured every 2 h over a 30-h incubation period.

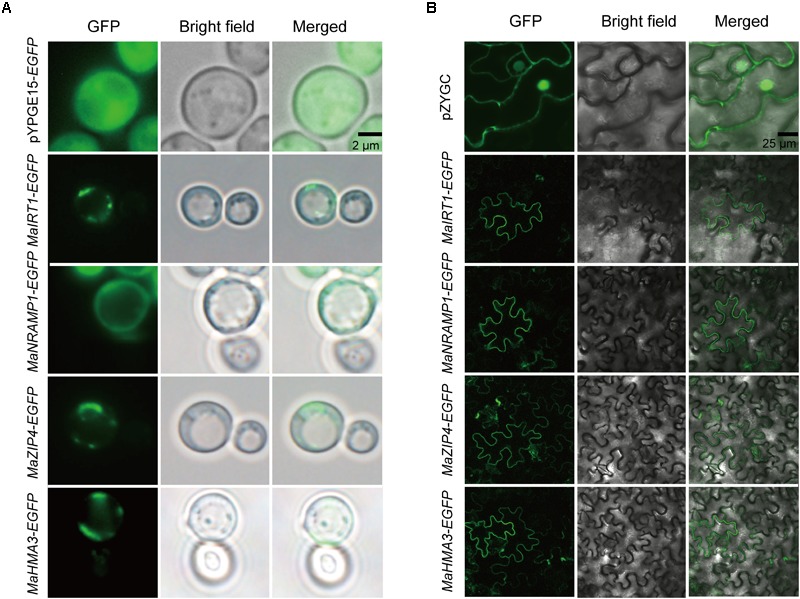

Subcellular Localization in Yeast and Tobacco Leaves

pYPGE15-EGFP were used to observe the localization of MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4 or MaHMA3 in yeast. The overexpression vector pZYGC [transformed from PLGNL by Lv Z, which contains the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and terminator] was used to observe the localization of those four transporter in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana). PCR primers, without the stop codon but containing restriction enzyme cutting sites, were designed (Supplementary Table S1).

These yeast constructs were introduced into the ΔYcf1 strain. Then, those yeast strains were cultured in liquid SD-Ura medium until the OD600 reached 1.0. The new constructs of pZYGC-MaIRT1, -MaNRAMP1, -MaZIP4, -MaHMA3 were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 via a freeze-thaw method (Chen et al., 1994). Then, those A. tumefaciens strains were injected into the tobacco leaf lamina for transient expression of EGFP (Sparkes et al., 2006; Luo et al., 2018). Fluorescent cells were imaged by FV1200 laser scanning confocal microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the data was carried out using parametric ANOVA, with multiple pairwise comparisons being carried out by Tukey’s test (P < 0.05). The data were analyzed and performed by Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States), SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States).

Results

Identification and Bioinformatics Analysis of ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP Genes From M. notabilis

We identified 9 MnZIPs, four MnNRAMPs, eight MnHMAs and 10 MnMTPs (a total of 31 genes) from the M. notabilis genome (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2), and the number of members of these four gene families in the Arabidopsis and rice genomes, according to previous research, are also shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 1.

ZIP, NRAMP, HMA and MTP genes in the Morus notabilis genome.

| Gene name | GenBank accession numbers | Genomic positiona | CDS length (bp) | Amino acid number | TM domains predictedb | Protein subcellular localization predictedc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnIRT1 | MG773132 | scaffold73:955306-957300:+ | 1056 | 351 | 8 | P |

| MnIRT2 | MG773131 | scaffold923:142877-145960:+ | 1077 | 358 | 7 | P |

| MnZIP1 | MG773133 | scaffold96:597491-600594:- | 1056 | 351 | 7 | P |

| MnZIP2 | MG773139 | Scaffold46:662828-664781:- | 996 | 331 | 9 | P |

| MnZIP3 | MG773137 | scaffold46:672440-675545:- | 1254 | 417 | 11 | P |

| MnZIP4 | MG773135 | scaffold804:172706-174858:+ | 1221 | 406 | 8 | P |

| MnZIP5 | MG773134 | scaffold611:86590-89167:- | 1077 | 358 | 7 | P |

| MnZIP6 | MG773136 | scaffold609:23407-26602:- | 1095 | 364 | 6 | P |

| MnZIP7 | MG773138 | scaffold1436:239650-241454:- | 1041 | 346 | 8 | P |

| MnNRAMP1 | MG773143 | scaffold410:250368-254753:- | 1530 | 509 | 10 | P |

| MnNRAMP2 | MG773141 | scaffold286:78033-81145:+ | 1596 | 531 | 12 | V |

| MnNRAMP3 | MG773140 | scaffold1633:86406-89064:+ | 1569 | 522 | 12 | V |

| MnNRAMP4 | MG773142 | scaffold1379:244650-249730:- | 1536 | 511 | 10 | P |

| MnHMA1 | MG773147 | scaffold939:110033-116937:- | 2496 | 831 | 5 | Ch |

| MnHMA2 | MG773144 | scaffold640:168074-174152:+ | 2847 | 948 | 7 | P |

| MnHMA3 | MG773150 | scaffold297:742794-749609:- | 2970 | 989 | 8 | P, G |

| MnHMA4 | MG773145 | scaffold1005:74488-79507:+ | 2901 | 966 | 8 | P, G |

| MnHMA5 | MG773149 | scaffold297:730431-736662:- | 2955 | 984 | 6 | P, G |

| MnHMA6 | MG773151 | scaffold1219:351792-370928:+ | 2853 | 950 | 3 | Ch |

| MnHMA7 | MG773146 | scaffold4905:16794-23010:- | 3000 | 999 | 7 | P, G |

| MnHMA8 | MG773148 | scaffold348:210110-217043:+ | 2691 | 896 | 3 | Ch |

| MnMTP1 | MG773160 | scaffold1303:555709-556884:- | 1176 | 391 | 6 | V |

| MnMTP2 | MG773153 | scaffold650:70488-75395:- | 1143 | 380 | 0 | M |

| MnMTP3 | MG773153 | scaffold789:836249-837526:- | 1293 | 430 | 6 | V |

| MnMTP4 | MG773153 | scaffold46:1049130-1050209:+ | 1086 | 361 | 6 | V |

| MnMTP5 | MG773153 | scaffold139:891910-895885:+ | 1185 | 394 | 4 | V |

| MnMTP6 | MG773153 | scaffold435:167772-172266:- | 1227 | 408 | 5 | G, V |

| MnMTP7 | MG773153 | scaffold2452:8263-14877:- | 1353 | 450 | 4 | G, V |

| MnMTP8 | MG773153 | scaffold989:550983-553310:- | 1230 | 409 | 5 | G, V |

| MnMTP9 | MG773153 | scaffold179:147396-151647:- | 1095 | 364 | 5 | G, V |

| MnMTP10 | MG773153 | scaffold179:132860-139500:- | 1272 | 423 | 4 | G, V |

aData from MorusDB. bNumber of transmembrane helices predicted with TMHMM Server. cWoLF PSORT and ProtComp 9.0 predictions: P (plasma membrane), V (vacuolar membrane), Ch (chloroplast), M (mitochondrion) and G (Golgi apparatus).

The identified MnZIPs encoded proteins that varied in length from 331 to 416 amino acids (AAs), and contained 6–11 transmembrane (TM) domains predicted with the TMHMM Server. MnZIPs also have a variable region between the TM-3 and TM-4 variable regions, containing a potential metal-binding domain, which is rich in conserved histidine residues (Supplementary Figure S1). The identified MnNRAMPs encoded proteins that varied in length from 509 to 531 AAs, and contained 10–12 TM domains. The identified MnHMAs encoded proteins that varied in length from 831 to 999 AAs, and contained 3–8 TM domains. The identified MnMTPs encoded proteins that varied in length from 361 to 450 AAs, and contained 4–6 TM domains, except for MnMTP2, which was predicted to lack a TM domain.

We used WoLF PSORT and ProtComp 9.0 to predict the location of each protein in the cell. These results showed that all MnZIPs, MnNRAMP1, 4 and MnHMA2 were localized to the plasma membrane; MnNRAMP2-3, MnMTP1, 3–5 were localized to the vacuolar membrane; MnHMA3-5 and 7 were localized to both the plasma membrane and the Golgi apparatus; MnMTP6-10 were localized to both the Golgi apparatus and the vacuolar membrane; while MnHMA1, 6, and 8 were localized to the chloroplast, with MnMTP2 being localized to the mitochondrion.

Phylogenetic Analyses, Classification and Functional Relatedness of the ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP Genes

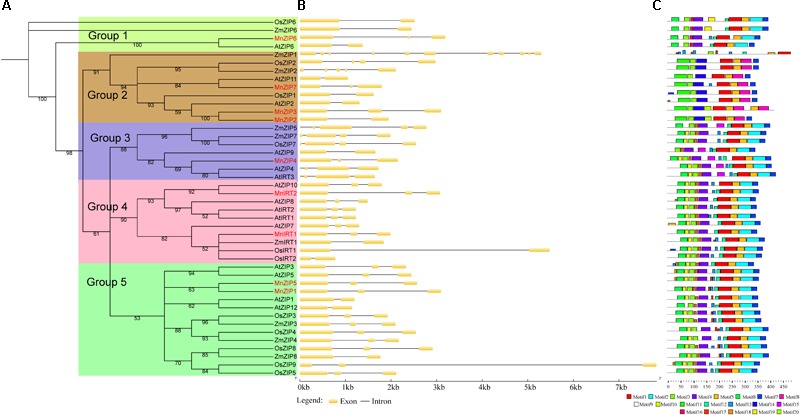

To examine the phylogenetic relationships among the ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP genes from A. thaliana, O. sativa, M. notabilis and other species, we performed phylogenetic analyses of the ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP protein sequences based on a maximum likelihood method, using TREE-PUZZLE 5.2 (Figure 1 and Supplementary Data Sheet S1). ZIPs were categorized into five groups (Groups 1–5), according to their phylogenetic relationships. NRAMPs were divided into two groups. HMAs were divided into two groups: Group 1 (Zn/Cd/Co/Pb) and Group 2 (Cu/Ag). MTPs were categorized into seven groups: Groups 1, 5, and 12 belonged to the Zn-CDFs, Groups 8 and 9 belonged to the Mn-CDFs, and Group 1 and Groups 6–9 belonged to the Fe/Zn-CDFs. In general, each group contained members of the transporter families from Morus, Arabidopsis, and rice. It is possible that these groups had evolved before the monocot-dicot divergence. There were four paralogous pairs: MnZIP1/MnZIP5, MnZIP2/MnZIP3, MnHMA3/MnHMA5, and MnMTP9/MnMTP10. The latter three pairs were localized to the same scaffold.

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic relationships, gene structure and motif composition of ZIP genes in Arabidopsis (At), rice (Os), Morus (Mn) and other species. (A) Multiple sequence alignments of the full-length protein sequences of ZIP genes were performed using ClustalX version 2.1. Phylogenetic trees were constructed with the maximum likelihood method using TREE-PUZZLE 5.3. rc16. The number of puzzling steps was set at 10,000 times. Every colored box represents a subfamily. (B) Exon/intron structures. Yellow boxes and black lines represent exons and introns, respectively. (C) Schematic representation of the conserved motifs elucidated by MEME 4.11.2. A number in the colored box represents each motif, and the black lines represent the non-conserved sequences.

The CDS of the MnZIP genes were disrupted by 1–2 introns. There were three introns in MnNRAMP Group 2, compared to 11 in Group 1. The number of introns in the MnHMA genes ranged from 5 to 16, while the number of introns in the MnMTP genes ranged from 5 to 12. Comparison of the exon/intron organization of the individual members of the four gene families showed that most of the closely related members shared similar structures, with regard both to the number of introns and the exon length. These results were highly consistent with the characteristics described in the above phylogenetic analysis.

The results of conserved domain analysis (data not shown) performed with SMART, Pfam and CDD showed that all ZIP proteins possessed one conserved ZIP domain, while all NRAMP proteins possessed one conserved NRAMP domain essential for their transporter activity. All HMA proteins in the foregoing species possessed one E1-E2_ATPase hydrolase domain. Members of Group 2 of the HMA proteins possessed HM-associated domains, and the number of these domains present in different clades ranged from 1 to 3. All MTP proteins in the above species possessed one cation efflux domain. The Group 12, Group 6, Group 8, and Group 9 MTPs in the above species possessed one ZT dimer domain.

In order to identify smaller individual motifs and more divergent patterns, we used the MEME program to study the diversity of ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP genes in Morus, Arabidopsis, rice, and other species. Details of the 20 motifs of the four transporter families are presented in Supplementary Data Sheet S2. In general, the number of motifs in the four transporter family proteins in Morus and the number of AAs spacing between adjoining protein motifs differed, a finding which was similar to that observed in the Arabidopsis and rice proteins.

There were common motifs among the most closely related members in the phylogenetic tree. Among the 44 ZIP sequences, more than 40 ZIP genes contained motifs 1, 3, 5, and 7. Group 2 ZIP sequences were different from the other Groups, containing motifs 8, 11, and 14, but lacking 2, 4, and 6. Among the 21 NRAMP sequences, more than 20 NRAMP genes contained motifs 1–9, 11, and 12. Compared with Group 1, Group 2 NRAMP genes contained motifs 10, 14, 16, and 17, but lacked motifs 13 and 15. Among the 37 HMA sequences, more than 30 HMA genes contained motifs 1–5, 8–11, 16, 18, and 19. Compared with Group 1, Group 2 NRAMPs contained motifs 6–7, 13–14, and 20, which may be related to their role in Cu/Ag transport. Among the 31 MTP sequences, the motifs of members of Groups 8 and 9 were similar, with 26 MTP genes containing motif 5. Some AA sites of these motifs may play important roles in the transport of cadmium or other ions. Among the selected yeast mutations expressing AtNRAMP4, three residues (L67V, E401K, and F413I) decreased Cd2+ sensitivity (Pottier et al., 2015).

Promoter Cis-Element Analysis

As primary signaling molecules, phytohormones such as jasmonic acid (JA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA), salicylic acid (SA), auxins, gibberellins (GA), ethylene (ET), and abscisic acid (ABA) (Saeed et al., 2003) enable plants to withstand abiotic stresses, including HMs (Luo et al., 2016). We identified putative cis-acting regulatory DNA elements based on the promoter sequences acquired (1500 bp upstream of the transcription start site). Analysis of the promoter sequences of members of the four gene families identified several cis-elements that were related to responsiveness to phytohormones and environmental stress signals (Supplementary Table S3). Among the 31 genes, 28 genes (90.32%) contained ABA-responsive cis-elements (ABRE/ARE), 22 genes (70.97%) contained SA-responsive cis-elements (TCA-element), 14 genes (45.16%) contained MeJA-responsive cis-elements (CGTCA-motif/TGACG-motif) and eight genes (25.81%) contained auxin-responsive cis-elements (TGA-element), while 11 genes (35.48%) contained GA-responsive cis-elements (GARE-motif). In addition, there were several genes where the promoter contained MYB-binding sites involved in drought-inducibility (MBS), heat stress-responsive and wounding- and pathogen-responsive motifs (W box/WUN-motif). All genes, except MnZIP2, contained more than three classes of cis-elements, which shows the diversity of the expression regulatory sequences associated with these genes.

Differential Expression Profiles of the ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP Genes

The RPKM was used to normalize the expression levels of the MnZIPs, MnNRAMPs, MnHMAs, and MnMTPs in five tissues (root, branch bark, bud, leaf, and flower), using M. notabilis RNA sequencing data19. Most genes showed different transcript levels among the five tissues, while the expression of MnNRAMP4 and MaMTP9 in buds and flowers, and the expression of MnHMA2 in leaf tissue were not detected (Figure 2). The transcript levels of the 31 genes can be classified into four groups (A–D; Figure 2), with the transcript abundance decreasing generally in the order C > D > B > A. Because some transporters have the same functions of Cd2+ transport, perhaps the genes which showed low expression in the five tissues do not play important roles in Cd2+ transport.

FIGURE 2.

The transcript levels of four Morus transporter gene families in five tissues. The transcript levels were depicted by color scale representing log10 values. The values were centered and scaled in the column direction. Red denotes high expression and green denotes low expression.

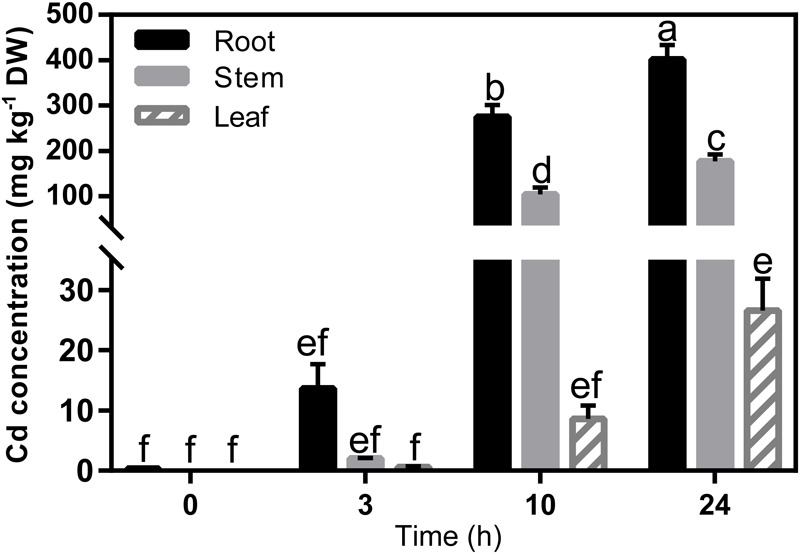

The Cd concentration in the seedlings increased significantly in all tissues within 24 h of exposure to Cd (Figure 3), which means that the translocation of Cd was very rapid. The expression profiles of the 31 genes in Ma-GY62 under Cd2+ stress were then compared (Figure 4). The roots, stems, and leaves were sampled at 0, 1, 3, 10, and 24 h after Cd2+ treatment. We cloned the CDS of the Ma-GY62 ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP genes, and the AA sequence identities between the Cd2+ transporters of M. notabilis and Ma-GY62 were high (≥87%) (Supplementary Table S4).

FIGURE 3.

Cd concentration in root, stem and leaf tissues of Ma-GY62 seedlings within 24 h of exposure to soil treated with 100 μM CdCl2. Values are the means ± standard error (n = 3) for the different parts of the plant. Any two samples with a common letter are not significantly different, according to Tukey’s test (P > 0.05).

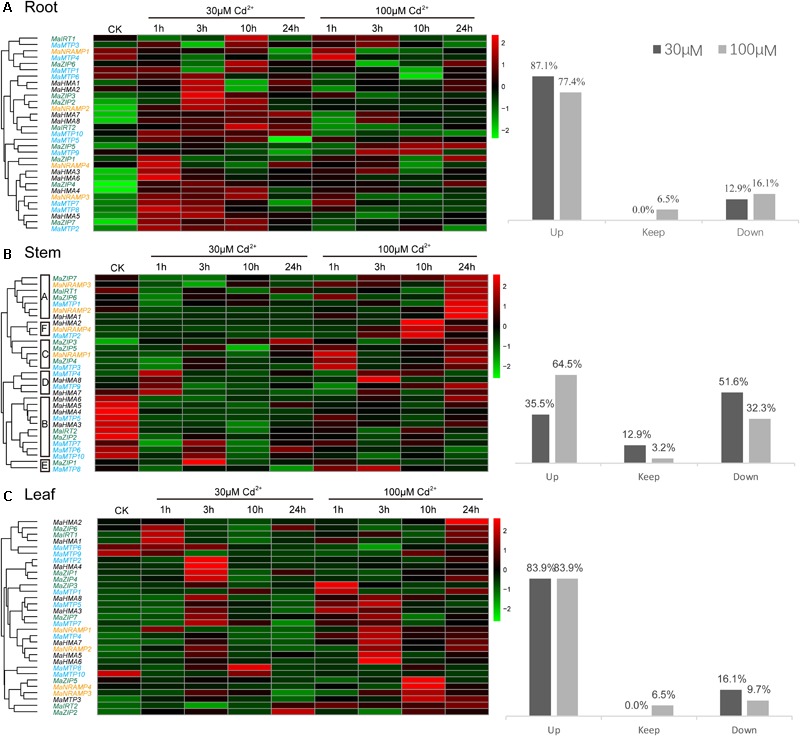

FIGURE 4.

The transcript levels of four transporter gene families in (A) root, (B) stem, and (C) leaf tissues of Ma-GY62 under Cd2+ stress. The transcript levels were depicted by color scale representing log10 values. The values were centered and scaled in the row direction. Red denotes high expression and green denotes low expression. The percentage of up-regulation, no significance difference, or down-regulation of the 31 genes in root, stem, and leaf, in the presence of 30 or 100 μM Cd2+, is to the right hand side of the pheatmap.

In roots, 87.1% of the 31 genes showed increased expression within 24 h of exposure to the low Cd2+ concentration (30 μM) treatment, but the time of peak up-regulation was different among the various genes. The expression of MaZIP1, 7, MaNRAMP4, MaHMA3, 6, MaMTP2, 5, 7-8 and 10 (37% of the total of 31 genes) reached the maximum at 1 h, while the expression of MaZIP2-3, 5-6, MaNRAMP2, MaHMA1-2, 5-6 (33.3%) was maximal at 3 h. The expression of genes MaIRT1-2, MaZIP6, MaNRAMP3, MaHMA4, MaHMA8, MaMTP3 (25.9%) reached the maximal value at 10 h, while the expression of MaHMA7 (3.7%) peaked at 24 h. The expression of genes MaNRAMP1, MaMTP1, 4 and 9 (12.9%) decreased within 24 h of exposure to Cd2+.

When the studies were repeated at the high Cd2+ concentration (100 μM), 77.4% of the 31 genes showed increased expression within 24 h, but, again, the times of maximal up-regulation were different. The expression of MaZIP1, 3, MaNRAMP2-3, MaHMA4, MaMTP4-5 and 7 (25.8% of the total of 31 genes) reached their maximum at 1 h, while that of MaIRT1, MaNRAMP4, MaHMA3, MaHMA7-8, MaMTP3 and 9 (22.6%) peaked at 3 h, with the expression of MaZIP5 and MaMTP2 (6.5%) reaching the maximum at 10 h, and that of MaZIP4, 6-7, MaHMA1-2 and 5 (19.4%) peaking at 24 h. The expression of genes MaIRT2, MaNRAMP1, MaMTP1, 6 and 10 (16.1%) showed decreased expression over the 24-h exposure period, while MaZIP2 and MaHMA6 (6.5%) showed no significant difference in expression in response to high Cd2+ concentration (100 μM). The maximum expression of those genes which showed increased expression under 30 μM Cd2+ stress was higher than that under 100 μM Cd2+ stress except for genes MaZIP5 and MaHMA8. MaNRAMP1 and MaMTP1 showed decreased expression under both 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ stress, while MaIRT2, MaMTP6, and MaMTP10 showed increased expression after 30 μM Cd2+ treatment and decreased expression after 100 μM Cd2+ treatment. In contrast, MaMTP4 and MaMTP9 showed decreased expression after 30 μM Cd2+ treatment but increased expression after 100 μM Cd2+ treatment.

In stems (Figure 4B), 35.5% of the 31 genes studied showed increased expression within 24 h of Cd exposure to the low Cd2+ concentration (30 μM) treatment, but the time of maximal expression differed between genes. The expression of MaHMA7-8, MaMTP4 and 9 (12.9%) was maximal at 1 h, while that of MaZIP1, 4-5, MaMTP2 and 7 (16.1%) peaked at 3 h. Genes MaZIP3 and MaNRAMP1 (6.5%) reached maximal expression at 24 h, while genes MaIRT1-2, MaZIP2, 6-7, MaNRAMP2-3, MaHMA3-6, MaMTP1, 5-6, 8 and 10 (51.6%) showed decreased expression during Cd2+ exposure, and genes MaNRAMP4, MaHMA1-2, MaMTP3 (12.9%) showed no significant difference in expression in response to Cd2+ exposure. At high Cd2+ concentration (100 μM) treatment, 64.5% of the 31 genes in stem tissue showed increased expression within 24 h, but the time of maximal up-regulation differed. The expression of genes MaZIP1, MaNRAMP1 and MaMTP3 (9.7%) was maximal at 1 h, while that of MaHMA8, MaMTP4 and 8 (9.7%) peaked at 3 h. The expression of MnZIP3, MaNRAMP4, MaHMA2 and MaMTP2 (12.9%) reached the maximum level at 10 h, while that of MaIRT1, MaZIP4-7, MaNRAMP2, MaHMA1, 7, MaMTP1 and 9 (32.3%) peaked at 24 h. Genes MaIRT2, MaZIP2, MaHMA3-6, MaMTP5-7 and 10 (32.3%) showed decreased expression over the 24 h period of exposure, while that of gene MaNRAMP3 (3.2%) showed no significant difference. The genes of Group B showed decreased expression under both 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ treatments except for MaMTP7, which showed increased expression after 30 μM Cd2+ treatment and decreased expression after 100 μM Cd2+ treatment. The genes of Groups C, D, and E, which showed increased expression after 30 μM Cd2+ treatment, also showed increased expression after 100 μM Cd2+ treatment. Genes MaNRAMP4 and MaHMA1-2 showed no significant difference in expression after 30 μM Cd2+ treatment but expression increased after 100 μM Cd2+ treatment. Interestingly, genes MaIRT1, MaZIP6-7, NRAMP2, MaMTP1 and 8 showed decreased expression after 30 μM Cd2+ treatment but increased expression after 100 μM Cd2+ treatment.

In leaves (Figure 4C), 83.9% of the 31 genes showed increased expression within 24 h of exposure to the low Cd2+ concentration (30 μM) treatment, but the time of maximal up-regulation differed between genes. The expression of genes MaIRT1, MaZIP6, MaNRAMP1, MaHMA1 and 2 (16.1%) peaked at 1 h, compared to the expression of MaZIP1, 3-4, 7, MaNRAMP2-3, MaHMA3-8, MaMTP2-5 and 7 (51.6%), which reached the maximal level at 3 h, while expression of MaMTP1 and 8 (6.5%) peaked at 10 h and that of MaIRT2 and MaZIP2 (6.5%) was maximal at 24 h. Meanwhile, genes MaZIP5, MaNRAMP4, MaMTP6, 9 and 10 (16.1%) showed decreased expression over the 24 h period. After treatment with high Cd2+ concentration (100 μM), 83.9% of the 31 genes showed increased expression within 24 h (the same proportion as with the low Cd2+ concentration (30 μM) treatment), but the time of maximal up-regulation was different. The expression of MaZIP3, MaHMA1, 3, MaMTP1 (12.9%) was maximal at 1 h while the expression of genes MaZIP7, MaNRAMP1-2, MaHMA5-8, MaMTP4-5, 7 (29%) peaked at 3 h, and that of genes MaZIP2-3, 5, MaNRAMP3-4 and MaMTP3 (19.4%) was maximal at 10 h. The expression of genes MaIRT1-2, MaZIP1, 4-5, MaHMA2, MaMTP2 (22.6%) peaked at 24 h. Meanwhile, genes MaMTP6, 9 and 10 (9.7%) showed decreased expression within the 24 h treatment period, and expression of MaHMA4 and MaMTP8 (6.5%) showed no significant difference over this period. MaMTP6, 9-10 showed decreased expression under both 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ treatments. In contrast, 77.4% of genes showed increased expression under both 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ treatments. Interestingly, genes MaZIP5 and MaNRAMP4 showed decreased expression after 30 μM Cd2+ treatment but increased expression after 100 μM Cd2+ treatment. On the other hand, MaHMA4 and MaMTP8, which showed decreased expression after 30 μM Cd2+ treatment, showed no significant difference after 100 μM Cd2+ treatment.

Heterologous Expression of Genes MaNRAMP1, MaHMA3, MaZIP4, and MaIRT1 in S. cerevisiae

Roots and leaves, which accumulated the highest amounts of the Cd taken up, can be harvested, baled, dried, and incinerated to achieve phytoremediation. Therefore, we selected several genes, which were highly expressed in root or leaf tissues, and which showed significant increases or decreases in response to Cd treatment. Under both Cd concentrations, MaNRAMP1 showed decreased expression in roots. Under 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ stress, MaHMA3 expression increased 22- and 14-fold, respectively, in the root, while that of MaZIP4 increased 10.5- and 9.7-fold, respectively, in the root. Moreover, MaIRT1 increased 20- and 43-fold under 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ stress, respectively, in leaves. These four transporter genes were predicted to be located in the plasma membrane.

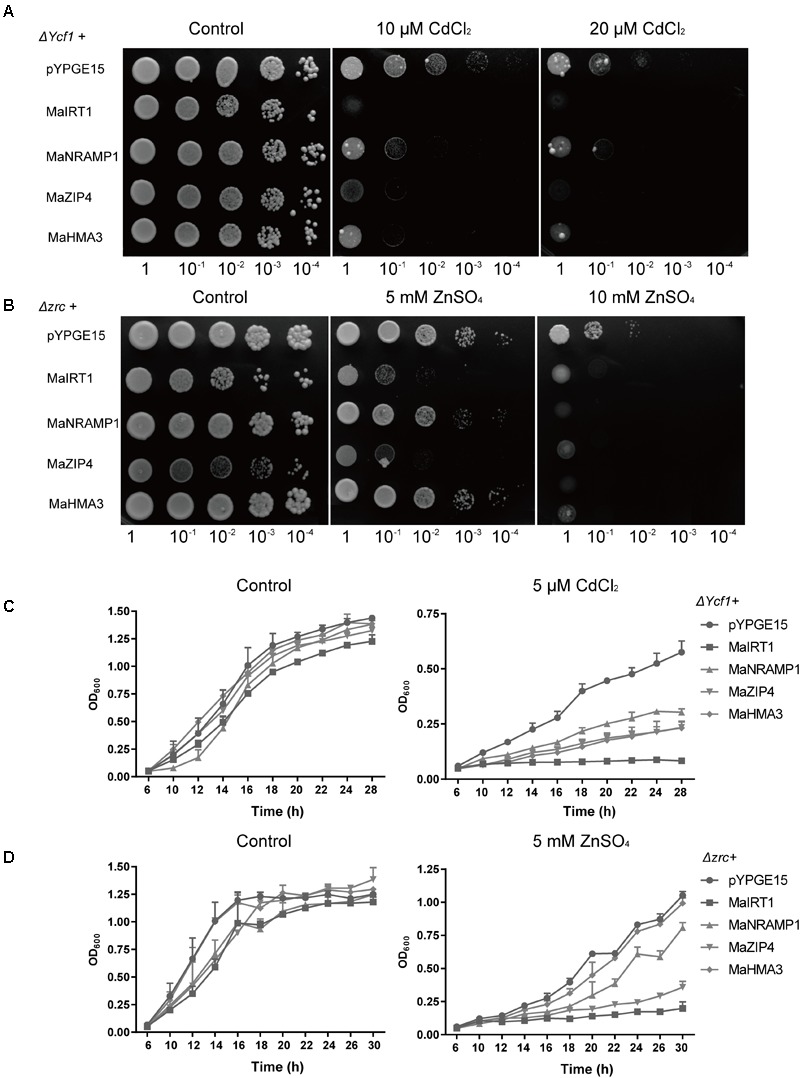

To investigate whether MaIRT1, MaNRANP1, MaZIP4, and MaHMA3 can transport Cd2+ and/or Zn2+, the cDNA of each of these four genes was heterologously expressed in yeast (ΔYcf1 and Δzrc strains) for functional assays. All strains of yeast expressing MaIRT1, MaNRANP1, MaZIP4, or MaHMA3 displayed considerably increased sensitivity to Cd (Figures 5A,C), whereas the expression of MaNRAMP1 and MaHMA3 did not alter the growth of yeast on medium containing 5 mM ZnSO4 (Figures 5B,D). These results suggest that MaIRT1 and MaZIP4 can transport both Zn2+ and Cd2+ into the yeast cell, while MaNRAMP1- or MaHMA3-mediated transport was more specific for Cd2+.

FIGURE 5.

Functional analysis of Ma-GY62 IRT1, NRAMP1, ZIP4 and HMA3 expression in yeast strains. (A) Heterologous expression of genes MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4, or MaHMA3 increased the Cd sensitivity of the ΔYcf1 strain. Growth of yeast strains transformed with the empty vector (pYPGE15) or MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4 or MaHMA3 on synthetic defined medium with 0, 10, or 20 μM CdCl2 was assessed. (B) Expression of MaIRT1 or MaZIP4 increased the Zn sensitivity of the Δzrc strain. Growth of yeast strains transformed with the empty vector (pYPGE15) or with the genes MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4, or MaHMA3 on synthetic defined medium with 0, 5, or 10 mM ZnSO4 was assessed. Yeast cells transformed with the empty vector or with genes MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4, or MaHMA3 were grown in liquid SD medium containing (C) 5 μM CdCl2 or (D) 5 mM ZnSO4 for 30 h.

MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4, and MaHMA3 Are Localized to the Plasma Membrane of Yeast and Tobacco

To further determine whether the subcellular localization of MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MAZIP4, and MaHMA3 is consistent with the predictions, and whether the result of subcellular localization in yeast is consistent with that in plants, the subcellular localization of these four transporter proteins was investigated using an EGFP fusion protein in yeast and tobacco (Figure 6). Compared with the controls, MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4, and MaHMA3 are all localized to the plasma membrane in both the yeast and tobacco cells.

FIGURE 6.

Subcellular localization of MaIRT1, MaNRAMP1, MaZIP4, and MaHMA3 in yeast and tobacco leaves. (A) Analyses of subcellular localization of the four transporter proteins in yeast strain ΔYcf1. pYPGE15-EGFP means the empty vector. Scale bar = 2 μm. (B) Analyses of subcellular localization of those four transporter proteins in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) leaf lamina. pZYGC means the empty vector. Scale bar = 25 μm.

Discussion

Multigene Family Members May Be Related to Functional Redundancy

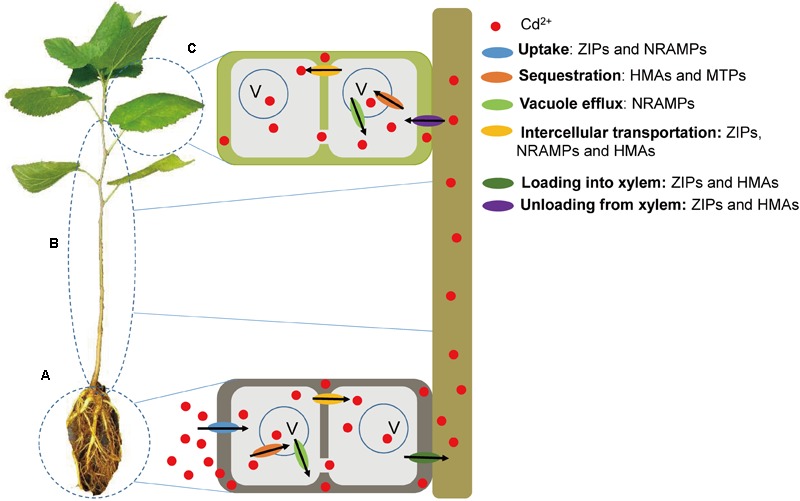

Cadmium is initially absorbed from the soil through the roots, and then proportions of the Cd2+ are either entrapped in root vacuoles or enter the shoot via the xylem. Cd2+ in the xylem of the stem can then be either transported to the leaves or redistributed through the phloem (Mendoza-Cózatl et al., 2011). Enhanced active metal transport, rather than metal complexation, is the key mechanism of hyperaccumulation, which can result in accumulation of high concentrations of HMs in aerial parts of plants (Leitenmaier and Kupper, 2013). In the present study, we identified 31 Morus genes, including ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP genes, which may be involved in Cd2+ uptake, translocation and sequestration in Morus (Figure 7). These multigene families are possibly adapted to the transport of various ions. Functional redundancies may also exist among these metal transporters. The expected side effects were minor in the transformants or mutants of OsHMA3, probably due to compensation by other transporters (Miyadate et al., 2011; Sasaki et al., 2014). MnZIP2/MnZIP3, MnHMA3/MnHMA5, and MnMTP9/MnMTP10 were localized to the same scaffolds, and are related as a result of tandem duplications. Although OsNRAMP1 and OsNRAMP5 both play roles in root Cd uptake, the contribution of OsNRAMP1 is probably insignificant compared to that of OsNramp5. OsNRAMP1 expression in roots is much lower than OsNRAMP5, while increased OsNRAMP1 expression did not increase root Cd uptake in the OsNRAMP5 mutant (Uraguchi and Fujiwara, 2013). Moreover, the transcript abundance of the 31 genes in the five tissues of Morus differed greatly and probably decreased in the order Group C > D > B > A. The higher expression of a gene may suggest a greater role for this gene in Cd2+ transport processes.

FIGURE 7.

The mechanisms of Cd2+ uptake, translocation and sequestration in mulberry may be mediated by ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP transporters. (A) At the root level, ZIP and NRAMP transporters are involved in Cd2+ uptake. HMA and MTP transporters are involved in Cd2+ sequestration into vacuole. Vacuole efflux is mediated by NRAMP transporters. Intercellular transportation is mediated by ZIP, NRAMP, and HMA transporters. (B) At the stem level, loading of Cd2+ into xylem and unloading of Cd2+ from xylem are mediated by ZIP and HMA transporters. (C) At the leaf level, HMA and MTP transporters are involved in Cd2+ sequestration into vacuole. Vacuole efflux is mediated by NRAMP transporters. Intercellular transportation is mediated by ZIP, NRAMP, and HMA transporters.

The Molecular Mechanism of Transporter Response to Cd2+ Stress in Roots

Cd2+ enters root cells via ZIP (OsIRT1, OsIRT2) and NRAMP (TcNRAMP3) transporters (Nakanishi et al., 2006; Wei et al., 2009). Cd2+ can also enter plant root cells via yellow-stripe 1-like proteins as a Cd-chelate complex (Curie et al., 2009). MaNRAMP1 and MaMTP1 showed reduced expression in roots under both 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ stress. Morus NRAMP1 was localized to the plasma membrane, and the expression of MnNRAMP1 was higher in roots than in other tissues. Morus MTP1, MTP4 and MTP9 belonged to Groups 1 and 9 in the MTP phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Data Sheet S1), in which the same group members were reported to transport Cd2+ (Yuan et al., 2012; Das et al., 2016). Cd2+ is harmful to the growth of plants, so, for the plant itself, the expression of transporters involving Cd uptake in the root would logically be decreased, and that of transporters involving Cd transport and sequestration in root cells would be increased to reduce the toxicity of Cd. Moreover, because of the similarities in chemical properties and interrelated metabolic pathways, there is a close correlation between Cd and Zn/Cu/Co/Mg (Feng et al., 2017). Due to the Cd-mediated competitive inhibition of the uptake and transport of Zn2+ or other ions, some genes would exhibit increased expression to regulate the balance of the essential elements they need. In this study, the genes which exhibited Cd2+-induced increase in expression were members of all four transporter families. Of those genes, the expression of MaHMA3 increased 22- and 14-fold under 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ stress, respectively, suggesting an important role in Cd transport in root cells, while the response of MaZIP4 expression (10.5- and 9.7-fold increases under low and high Cd concentrations, respectively) indicates that it may play a similar role.

Cd2+ uptake in poplar roots was associated with activities of plasma membrane proton ATPases, and with the increased expression levels of several putative metal transporter genes, such as NRAMP1.1, NRAMP1.3, ZIP2, and ZIP6.2 (He et al., 2015). Rome et al. (2016) also reported that P. alba NRAMP1, IRT1a and IRT1b genes increased expression in roots after 1 day of CdCl2 treatment. Expression of the P. alba HMA gene increased in roots after 1-week and 1-month exposure to CdCl2 (Rome et al., 2016). The transcript abundance of TcNRAMP3, from the Cd-hyperaccumulator T. (Noccaea) caerulescens, increased steadily up to 96 h after treatment with 500 μM CdCl2 (Wei et al., 2009). CsMTP9 mRNA level increased ∼2.5-fold upon cucumber plant exposure to Cd (Migocka et al., 2015b). However, Cd did not significantly affect CsMTP1 and CsMTP4 expression, nor protein levels in cucumber roots (Migocka et al., 2015a). Compared with the low Cd2+ concentration treatment, more genes showed decreased expression or no significant difference after high Cd2+ concentration treatment. In addition, the maximum expression of those genes, which showed increased Cd-induced expression under 30 μM Cd2+ stress, was higher than the corresponding values expressed under 100 μM Cd2+ stress, except for genes MaZIP5 and MaHMA8. That observation may be related to the fact that a high Cd concentration is more toxic to plant roots than a low concentration. Maybe different genes function in different tissues, such as the roots. Interestingly, when MaNRAMP1 (where expression in the root was significantly decreased under Cd2+ stress) and MaZIP4 or MaHMA3 (where expression in the root was significantly increased under Cd2+ stress) were heterologously expressed in yeast, the yeast cells showed considerably increased sensitivity to Cd2+.

The Molecular Mechanism of Transporter Response to Cd2+ Stress in Stems

The Cd movement from roots to aerial tissues occurs through transpiration-driven xylem loading, with symplastic and apoplastic transport of free Cd2+ or Cd-chelate complexes (Kranner and Colville, 2011; Lux et al., 2011). Several studies have reported that HMA and ZIP family transporters participate in Cd transport across the plasma membrane and into plant shoots (Hanikenne et al., 2008; Wong and Cobbett, 2009). OsZIP3, located in the nodes, is involved in unloading Zn from the xylem into the enlarged vascular bundles of rice, while OsZIP4, 5 and 8 should be responsible for root-to-shoot Zn translocation (Sasaki et al., 2015). Morus ZIP1 and 5, which belong to the same group as OsZIP3-5 and 8, may be involved in Cd transport in the stem. Under both 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ treatments, MaZIP1 (5.1- and 1.9-fold increases, respectively) and MaZIP4 (2.3- and 3.7-fold increases, respectively) showed increased expression. OsHMA2, AtHMA2 and 4 are responsible for Cd translocation to shoots (Wong and Cobbett, 2009; Takahashi et al., 2012; Cun et al., 2014). Morus HMA1 and HMA2 belong to the same Group as the above HMAs. Compared with Morus HMA1, the expression of Morus HMA2 was very low in the five different tissues. MaHMA1 showed no significant difference in expression after 30 μM Cd2+ treatment but increased expression (10.8-fold) after 100 μM Cd2+ treatment. In addition, MaHMA8 (5.6- and 10.7-fold increases under low and high Cd2+ treatments, respectively) may also play an important role in Cd transport in stem cells. Compared with the low Cd2+ concentration treatment, more genes showed increased expression after high Cd2+ concentration treatment. This phenomenon may be related to the fact that high Cd concentration is more toxic to plant roots, so that the expression of genes associated with root-to-shoot translocation increased to reduce Cd concentration in the roots. In stems, expression of PaHMA2 in polar increased after 1-month Cd treatment (Rome et al., 2016). The PtHMA1 expression level increased in the stem after 1 h Cd treatment (Li et al., 2015). Expression of OsHMA2 in the roots did not change in the presence of Cd, but expression in the shoots increased in the presence of 1 mM Cd (Takahashi et al., 2012).

The Molecular Mechanism of Transporter Response to Cd2+ Stress in Leaves

The majority of Cd taken up into Morus leaves was bound to the cell wall in the leaves (Zhou et al., 2015a). When Cd2+ transport into the mesophyll causes inhibition of photosynthesis (Kupper et al., 2007), vacuolar compartmentalization is important in order to reduce Cd-induced toxicity, as it reduces the movement of free Cd into the cytosol (Choppala et al., 2014). In this study, similar numbers of genes showed increased expression under both 30 and 100 μM Cd2+ treatments in leaves. Interestingly, MaIRT1 (20- and 43-fold increases under low and high Cd2+ concentrations, respectively), MaHMA4 (4.2- and 3-fold increases) and MaNRAMP4 (5.2- and 3.1-fold increases) showed significant increases, and the expression of these genes within their respective families was very high in leaves. The expression level of PtHMA1 in the leaves gradually increased during exposure to Cd (Li et al., 2015). Growth on elevated Cd concentrations caused the increase of ZNT1 expression in the spongy mesophyll of young and mature leaves (Kupper and Kochian, 2010). When MaIRT1 was heterologously expressed in yeast, the cells showed considerably increased sensitivity to Cd2+.

Compared to non-accumulator plants, metal hyperaccumulation in hyperaccumulators relies on (at least partly) higher expression (up to 200-fold higher) of various metal transporter genes (Leitenmaier and Kupper, 2013). However, metal transporters show diverse levels of selectivity based on the family to which they belong. The mechanisms of the regulation of expression of the HM transporter genes are largely unknown. There are a few transcription factors known to be involved in Cd stress response, such as CaPF1 (an ERF/AP2-like transcription factor), TaHSFA4a (a member of the heat shock transcription factor family), microRNA268 and OsMYB45 (Tang et al., 2005; Donghwan et al., 2009; Ding et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2017). In our study, several transporter genes were shown to contain MYB binding sites and/or heat stress responsive sites in their promoter sequences. The mechanisms of transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene regulation of HM-specific and non-specific transporters are complex, a topic which needs further functional analysis.

In this study, we identified 31 Morus putative transporter genes, analyzed their possible regulation and expression patterns carefully, and performed yeast functional analysis on candidate genes. These results will provide useful information for understanding the complex molecular mechanism of response of mulberry trees under Cd2+ stress, which could be exploited in the future for phytoremediation purposes.

Author Contributions

WF, CL, and AZ conceived and designed the experiments. WF and MQ performed the experiments. WF, CL, BC, and DL analyzed the data. WF, CL, MQ, BC, DL, ZX, and AZ contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. WF, CL and AZ wrote the paper. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer MR-P and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Acknowledgments

ΔYcf1 and Δzrc were kindly provided by Xiaoe Yang (Zhejiang University, Zhejiang, China).

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the China Agriculture Research System (No. CARS-18-ZJ0201) and the Special Fund for Agro-Scientific Research in the Public Interest of China (No. 201403064).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00879/full#supplementary-material

Amino acid alignment of ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP protein.

The sequences of the primers used in this study.

The number of ZIP, NRAMP, HMA and MTP transporters in Arabidopsis, rice and Morus.

The putative cis-elements that are related to stress in the region -1500 upstream of the ATG translation initiation site of four gene families in M. notabilis.

Amino acid sequence identities between the heavy metal transporter of M. notabilis and Ma-GY62.

Phylogenetic analyses, classification and functional relatedness of the NRAMP, HMA, and MTP genes.

Details of the 20 motifs of the four transporter families.

References

- Arrivault S., Senger T., Kramer U. (2006). The Arabidopsis metal tolerance protein AtMTP3 maintains metal homeostasis by mediating Zn exclusion from the shoot under Fe deficiency and Zn oversupply. Plant J. 46 861–879. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashfaq M., Ahmad S., Sagheer M., Hanif M. A., Abbas S. K., Yasir M. (2012). Bioaccumulation of chromium (III) in silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) in relation to mulberry, soil and wastewater metal concentrations. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 22 627–634. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Boden M., Buske F. A., Frith M., Grant C. E., Clementi L., et al. (2009). MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 W202–W208. 10.1093/nar/gkp335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D. M., Guarente L. (1991). High-efficiency transformation of yeast by electroporation. Methods Enzymol. 194 182–187. 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94015-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello-Hurtado F., Ramos J. (2004). Isolation and functional analysis of the glycerol permease activity of two new nodulin-like intrinsic proteins from salt stressed roots of the halophyte Atriplex nummularia. Plant Sci. 166 633–640. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2003.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y. X., Zhu P. P., Liu C. Y., Zhao A. C., Yu J., Wang C. H., et al. (2016). Characterization and expression analysis of cDNAs encoding abscisic acid 8’-hydroxylase during mulberry fruit maturation and under stress conditions. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 127 237–249. 10.1007/s11240-016-1047-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cailliatte R., Lapeyre B., Briat J. F., Mari S., Curie C. (2009). The NRAMP6 metal transporter contributes to cadmium toxicity. Biochem. J. 422 217–228. 10.1042/Bj20090655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Nelson R. S., Sherwood J. L. (1994). Enhanced recovery of transformants of Agrobacterium tumefaciens after freeze-thaw transformation and drug selection. Biotechniques 16 664–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choppala G., Saifullah Bolan N., Bibi S., Iqbal M., Rengel Z., et al. (2014). Cellular mechanisms in higher plants governing tolerance to cadmium toxicity. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 33 374–391. 10.1080/07352689.2014.903747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S., Aarts M. G. M., Thomine S., Verbruggen N. (2013). Plant science: the key to preventing slow cadmium poisoning. Trends Plant Sci. 18 92–99. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cun P., Sarrobert C., Richaud P., Chevalier A., Soreau P., Auroy P., et al. (2014). Modulation of Zn/Cd P1B2-ATPase activities in Arabidopsis impacts differently on Zn and Cd contents in shoots and seeds. Metallomics 6 2109–2116. 10.1039/c4mt00182f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C., Cassin G., Couch D., Divol F., Higuchi K., Jean M. L., et al. (2009). Metal movement within the plant: contribution of nicotianamine and yellow stripe 1-like transporters. Ann. Bot. 103 1–11. 10.1093/aob/mcn207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das N., Bhattacharya S., Maiti M. K. (2016). Enhanced cadmium accumulation and tolerance in transgenic tobacco overexpressing rice metal tolerance protein gene OsMTP1 is promising for phytoremediation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 105 297–309. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.04.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Wang Y., Jiang Z., Wang F., Jiang Q., Sun J., et al. (2017). microRNA268 overexpression affects rice seedling growth under cadmium stress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65 5860–5867. 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donghwan S., Jaeung H., Joohyun L., Sichul L., Yunjung C., An G. H., et al. (2009). Orthologs of the class A4 heat shock transcription factor HsfA4a confer cadmium tolerance in wheat and rice. Plant Cell 21 4031–4043. 10.1105/tpc.109.066902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Guo Q., Liu C., Liu X., Zhang M., Long D., et al. (2018). Two mulberry phytochelatin synthase genes confer zinc/cadmium tolerance and accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis and tobacco. Gene 645 95–104. 10.1016/j.gene.2017.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Han L., Chao D., Liu Y., Zhang Y., Wang R., et al. (2017). Ionomic and transcriptomic analysis provides new insight into the distribution and transport of cadmium and arsenic in rice. J. Hazard. Mater. 331 246–256. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.02.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa E. (2008). Are more restrictive food cadmium standards justifiable health safety measures or opportunistic barriers to trade? An answer from economics and public health. Sci. Total Environ. 389 1–9. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gad S. C. (2014). Cadmium. Encycl. Toxicol. 39 613–616. 10.1016/B978-0-12-386454-3.00823-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids Symp. Ser. 41 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hanikenne M., Talke I. N., Haydon M. J., Lanz C., Nolte A., Motte P., et al. (2008). Evolution of metal hyperaccumulation required cis-regulatory changes and triplication of HMA4. Nature 453 391–395. 10.1038/nature06877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Li H., Ma C., Zhang Y., Polle A., Rennenberg H., et al. (2015). Overexpression of bacterial γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase mediates changes in cadmium influx, allocation and detoxification in poplar. New Phytol. 205 240–254. 10.1111/nph.13013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Jin J. P., Guo A. Y., Zhang H., Luo J. C., Gao G. (2015). GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31 1296–1297. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Yu Y., Chen Q., Mu G., Shen Z., Zheng L. (2017). OsMYB45 plays an important role in rice resistance to cadmium stress. Plant Sci. 264 1–8. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Takahashi R., Bashir K., Shimo H., Senoura T., Sugimoto K., et al. (2012). Characterizing the role of rice NRAMP5 in manganese, iron and cadmium transport. Sci. Rep. 2:286. 10.1038/srep00286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis R. S., Sherson S. M., Cobbett C. S. (2009). Functional analysis of the heavy metal binding domains of the Zn/Cd-transporting ATPase, HMA2, in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 181 79–88. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02637.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi M., Kobae Y., Mimura T., Maeshima M. (2008). Deletion of a histidine-rich loop of AtMTP1, a vacuolar Zn2+/H+ antiporter of Arabidopsis thaliana, stimulates the transport activity. J. Biol. Chem. 283 8374–8383. 10.1074/jbc.M707646200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer U. (2010). Metal hyperaccumulation in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61 517–534. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranner I., Colville L. (2011). Metals and seeds: biochemical and molecular implications and their significance for seed germination. Environ. Exp. Bot. 72 93–105. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.05.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper H., Kochian L. V. (2010). Transcriptional regulation of metal transport genes and mineral nutrition during acclimatization to cadmium and zinc in the Cd/Zn hyperaccumulator, Thlaspi caerulescens (Ganges population). New Phytol. 185 114–129. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper H., Parameswaran A., Leitenmaier B., Trtilek M., Setlik I. (2007). Cadmium-induced inhibition of photosynthesis and long-term acclimation to cadmium stress in the hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. New Phytol. 175 655–674. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V., Lelievre F., Bolte S., Hames C., Alcon C., Neumann D., et al. (2005). Mobilization of vacuolar iron by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is essential for seed germination on low iron. EMBO J. 24 4041–4051. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., et al. (2007). Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23 2947–2948. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitenmaier B., Kupper H. (2013). Compartmentation and complexation of metals in hyperaccumulator plants. Front. Plant Sci. 4:374. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescot M., Dehais P., Thijs G., Marchal K., Moreau Y., Van de Peer Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 325–327. 10.1093/nar/30.1.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Bork P. (2016). Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 W242–W245. 10.1093/nar/gkw290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Xu X., Hu X., Liu Q., Wang Z., Zhang H., et al. (2015). Genome-wide analysis and heavy metal-induced expression profiling of the HMA gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1149. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. F., Hassan Z., Talukdar S., Schat H., Aarts M. G. M. (2016). Expression of the ZNT1 zinc transporter from the metal hyperaccumulator Noccaea caerulescens confers enhanced zinc and cadmium tolerance and accumulation to Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 11:e0149750. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Li H., Xiang Z., He N. (2018). Identification of Morus notabilis MADS-box genes and elucidation of the roles of MnMADS33 during endodormancy. Sci. Rep. 8:5860. 10.1038/s41598-018-23985-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z. B., He J., Polle A., Rennenberg H. (2016). Heavy metal accumulation and signal transduction in herbaceous and woody plants: paving the way for enhancing phytoremediation efficiency. Biotechnol. Adv. 34 1131–1148. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lux A., Martinka M., Vaculik M., White P. J. (2011). Root responses to cadmium in the rhizosphere: a review. J. Exp. Bot. 62 21–37. 10.1093/jxb/erq281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Cózatl D. G., Jobe T. O., Hauser F., Schroeder J. I. (2011). Long-distance transport, vacuolar sequestration, tolerance, and transcriptional responses induced by cadmium and arsenic. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14 554–562. 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migocka M., Kosieradzka A., Papierniak A., Maciaszczyk-Dziubinska E., Posyniak E., Garbiec A., et al. (2015a). Two metal-tolerance proteins, MTP1 and MTP4, are involved in Zn homeostasis and Cd sequestration in cucumber cells. J. Exp. Bot. 66 1001–1015. 10.1093/jxb/eru459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migocka M., Papierniak A., Kosieradzka A., Posyniak E., Maciaszczyk-Dziubinska E., Biskup R., et al. (2015b). Cucumber metal tolerance protein CsMTP9 is a plasma membrane H+-coupled antiporter involved in the Mn2+ and Cd2+ efflux from root cells. Plant J. 84 1045–1058. 10.1111/tpj.13056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyadate H., Adachi S., Hiraizumi A., Tezuka K., Nakazawa N., Kawamoto T., et al. (2011). OsHMA3, a P1B-type of ATPase affects root-to-shoot cadmium translocation in rice by mediating efflux into vacuoles. New Phytol. 189 190–199. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanini B., Blaudez D., Jeandroz S., Sanders D., Chalot M. (2007). Phylogenetic and functional analysis of the Cation Diffusion Facilitator (CDF) family: improved signature and prediction of substrate specificity. BMC Genomics 8:107. 10.1186/1471-2164-8-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel M., Crouzet J., Gravot A., Auroy P., Leonhardt N., Vavasseur A., et al. (2009). AtHMA3, a P-1B-ATPase allowing Cd/Zn/Co/Pb vacuolar storage in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 149 894–904. 10.1104/pp.108.130294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno I., Norambuena L., Maturana D., Toro M., Vergara C., Orellana A., et al. (2008). AtHMA1 is a thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+/heavy metal pump. J. Biol. Chem. 283 9633–9641. 10.1074/jbc.M800736200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi H., Ogawa I., Ishimaru Y., Mori S., Nishizawa N. K. (2006). Iron deficiency enhances cadmium uptake and translocation mediated by the Fe2+ transporters OsIRT1 and OsIRT2 in rice. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 52 464–469. 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2006.00055.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson P. E., Fletcher J. S. (2000). Ecological recovery of vegetation at a former industrial sludge basin and its implications to phytoremediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 7 195–204. 10.1007/Bf02987348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovecka M., Takac T. (2014). Managing heavy metal toxicity stress in plants: biological and biotechnological tools. Biotechnol. Adv. 32 73–86. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottier M., Oomen R., Picco C., Giraudat J., Scholzstarke J., Richaud P., et al. (2015). Identification of mutations allowing Natural Resistance Associated Macrophage Proteins (NRAMP) to discriminate against cadmium. Plant J. 83 625–637. 10.1111/tpj.12914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin I., Smith R. D., Salt D. E. (1997). Phytoremediation of metals: using plants to remove pollutants from the environment. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 8 221–226. 10.1016/S0958-1669(97)80106-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rome C., Huang X. Y., Danku J., Salt D. E., Sebastiani L. (2016). Expression of specific genes involved in Cd uptake, translocation, vacuolar compartmentalisation and recycling in Populus alba Villafranca clone. J. Plant Physiol. 202 83–91. 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A. I., Sharov V., White J., Li J., Liang W., Bhagabati N., et al. (2003). TM4: A free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques 34 374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A., Yamaji N., Ma J. F. (2014). Overexpression of OsHMA3 enhances Cd tolerance and expression of Zn transporter genes in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 65 6013–6021. 10.1093/jxb/eru340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A., Yamaji N., Mitani-Ueno N., Kashino M., Ma J. F. (2015). A node-localized transporter OsZIP3 is responsible for the preferential distribution of Zn to developing tissues in rice. Plant J. 84 374–384. 10.1111/tpj.13005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneurin-Berny D., Gravot A., Auroy P., Mazard C., Kraut A., Finazzi G., et al. (2006). HMA1 a new Cu-ATPase of the chloroplast envelope, is essential for growth under adverse light conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 281 2882–2892. 10.1074/jbc.M508333200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid M., Dumat C., Khalid S., Niazi N. K., Antunes P. M. (2016). Cadmium bioavailability, uptake, toxicity and detoxification in soil-plant system. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 241 73–137. 10.1007/398-2016-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes I. A., Runions J., Kearns A., Hawes C. (2006). Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat. Protoc. 1 2019–2025. 10.1038/nprot.2006.286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel M. (2010). The phylogenetic handbook: a practical approach to phylogenetic analysis and hypothesis testing edited by Lemey, P., Salemi, M., and Vandamme, A.-M. Biometrics 66 324–325. 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2010.01388.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens B. W., Cook D. R., Grusak M. A. (2011). Characterization of zinc transport by divalent metal transporters of the ZIP family from the model legume Medicago truncatula. Biometals 24 51–58. 10.1007/s10534-010-9373-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R., Ishimaru Y., Senoura T., Shimo H., Ishikawa S., Arao T., et al. (2011). The OsNRAMP1 iron transporter is involved in Cd accumulation in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 62 4843–4850. 10.1093/jxb/err136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R., Ishimaru Y., Shimo H., Ogo Y., Senoura T., Nishizawa N. K., et al. (2012). The OsHMA2 transporter is involved in root-to-shoot translocation of Zn and Cd in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 35 1948–1957. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28 2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Charles T. M., Newton R. J. (2005). Overexpression of the pepper transcription factor CaPF1 in transgenic Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana Mill.) confers multiple stress tolerance and enhances organ growth. Plant Mol. Biol. 59 603–617. 10.1007/s11103-005-0451-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomine S., Wang R. C., Ward J. M., Crawford N. M., Schroeder J. I. (2000). Cadmium and iron transport by members of a plant metal transporter family in Arabidopsis with homology to Nramp genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 4991–4996. 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraguchi S., Fujiwara T. (2013). Rice breaks ground for cadmium-free cereals. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16 328–334. 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USGS (2017). Available at: https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/cadmium/index.html#mcs [accessed November 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- Verret F., Gravot A., Auroy P., Leonhardt N., David P., Nussaume L., et al. (2004). Overexpression of AtHMA4 enhances root-to-shoot translocation of zinc and cadmium and plant metal tolerance. FEBS Lett. 576 306–312. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert G., Grotz N., Dedaldechamp F., Gaymard F., Guerinot M. L., Briat J. F., et al. (2002). IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 14 1223–1233. 10.1105/tpc.001388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C. J., Liu X. Q., Long D. P., Guo Q., Fang Y., Bian C. K., et al. (2014). Molecular cloning and expression analysis of mulberry MAPK gene family. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 77 108–116. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Chai T., Zhang Y., Han L., Xu J., Guan Z. (2009). The Thlaspi caerulescens NRAMP homologue TcNRAMP3 is capable of divalent cation transport. Mol. Biotechnol. 41 15–21. 10.1007/s12033-008-9088-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. K. E., Cobbett C. S. (2009). HMA P-type ATPases are the major mechanism for root-to-shoot Cd translocation in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 181 71–78. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Yamaji N., Yamane M., Kashino-Fujii M., Sato K., Feng M. J. (2016). The HvNramp5 transporter mediates uptake of cadmium and manganese, but not iron. Plant Physiol. 172 1899–1910. 10.1104/pp.16.01189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Yu M., Xu F., Yu Y., Liu C., Li J., et al. (2015). Identification and expression analysis of the 14-3-3 gene family in the mulberry tree. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 33 1–10. 10.1007/s11105-015-0877-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L. Y., Yang S. G., Liu B. X., Zhang M., Wu K. Q. (2012). Molecular characterization of a rice metal tolerance protein, OsMTP1. Plant Cell Rep. 31 67–79. 10.1007/s00299-011-1140-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S. L., Shang X. J., Duo L. (2013). Accumulation and spatial distribution of Cd, Cr, and Pb in mulberry from municipal solid waste compost following application of EDTA and (NH4)2SO4. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R 20 967–975. 10.1007/s11356-012-0992-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L. Y., Zhao Y., Wang S. F. (2015a). Cadmium transfer and detoxification mechanisms in a soil-mulberry-silkworm system: phytoremediation potential. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R 22 18031–18039. 10.1007/s11356-015-5011-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L. Y., Zhao Y., Wang S. F., Han S. S., Liu J. (2015b). Lead in the soil-mulberry (Morus alba L.)-silkworm (Bombyx mori) food chain: Translocation and detoxification. Chemosphere 128 171–177. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Amino acid alignment of ZIP, NRAMP, HMA, and MTP protein.

The sequences of the primers used in this study.

The number of ZIP, NRAMP, HMA and MTP transporters in Arabidopsis, rice and Morus.

The putative cis-elements that are related to stress in the region -1500 upstream of the ATG translation initiation site of four gene families in M. notabilis.

Amino acid sequence identities between the heavy metal transporter of M. notabilis and Ma-GY62.

Phylogenetic analyses, classification and functional relatedness of the NRAMP, HMA, and MTP genes.

Details of the 20 motifs of the four transporter families.