Abstract

Background

Nursing home (NH) residents are frequent users of emergency departments (ED) and while prior research suggests that repeat visits are common, there is little data describing this phenomenon. Our objectives were to describe repeat ED visits over one year, identify risk factors for repeat use, and characterize “frequent” ED visitors.

Methods

Using provincial administrative data from Ontario, Canada, we identified all NH residents 65 years or older who visited an ED at least once between January 1 and March 31, 2010 and then followed them for one year to capture all additional ED visits. Frequent ED visitors were defined as those who had 3 or more repeat ED visits. We used logistic regression to estimate risk factors for any repeat ED visit and for being a frequent visitor and Andersen-Gill regression to estimate risk factors for the rate of repeat ED visits.

Results

In a cohort of 25,653 residents (mean age 84.5 (SD = 7.5) years, 68.2% female), 48.8% had at least one repeat ED visit. Residents who experienced a repeat ED visit were generally similar to others but they tended to be slightly younger, have a higher proportion male, and a higher proportion with minimal cognitive or physical impairment. Risk factors for a repeat ED visit included: being male (adjusted odds ratio 1.27, (95% confidence interval 1.19–1.36)), diagnoses such as diabetes (AOR 1.28 (1.19–1.37)) and congestive heart failure (1.26 (1.16–1.37)), while severe cognitive impairment (AOR 0.92 (0.84–0.99)) and 5 or more chronic conditions (AOR 0.82 (0.71–0.95)) appeared protective. Eleven percent of residents were identified as frequent ED visitors, and they were more often younger then 75 years, male, and less likely to have Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias than non-frequent visitors.

Conclusions

Repeat ED visits were common among NH residents but a relatively small group accounted for the largest number of visits. Although there were few clear defining characteristics, our findings suggest that medically complex residents and younger residents without cognitive impairments are at risk for such outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12877-018-0854-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Repeated events, Recurrent events, Long-term care, Emergency, Transfers

Background

Emergency departments (EDs) are important sites of care for nursing home (NH) residents; however, the frequency at which residents are transferred to EDs has been cause for concern and has raised questions about the extent to which such transfers are appropriate or avoidable [1]. Substantial research has sought to quantify the frequency of ED visits from NHs, in particular those that may be amenable to preventive interventions. Despite the volume of research, little attention has been paid to the issue of repeat ED visits, that is individual residents with multiple transfers, even though early studies reported a greater number of visits than residents in their cohorts [2, 3]. More recent studies report similar findings, including a study using National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey data that reported an average of 1.8 visits per resident per year [4]. Beyond such simple statistics, there is little data describing the frequency of repeat ED visits from NHs or the residents who make multiple visits.

In the general (non-NH) population, a small proportion of individuals (4–8%) accounts for a relatively large share of all ED visits [5, 6]. This group of “frequent ED users” has been shown to be fairly heterogeneous but are more likely to experience poor physical and mental health, and problems with substance abuse than other ED users [7–9]. Frequent ED use does not appear to be associated with insurance coverage or having a regular source of care [10, 11]. Among older adults in the general population, nearly 15% return to the ED within 30 days of an initial visit. For this group, return to the ED is associated with cognitive impairment, multiple chronic conditions, depression, and a history of prior ED use [12].

NH residents are a highly vulnerable group characterized by older age, multiple chronic conditions, and advanced cognitive and physical impairments. A better understanding of outcomes, such as repeated ED transfers, is critical to ensuring improved care for residents. By identifying how frequently repeated ED transfers from NHs occur and which residents are at greatest risk, we can begin to identify when and where interventions to improve resident care may be most successful in reducing preventable ED transfers. In this study, we had three objectives: 1) to describe all repeat ED transfers made by a cohort of LTC residents over one year; 2) to identify resident characteristics associated with repeat ED transfer; and 3) to characterize a group of “frequent ED users” defined as residents who experienced 4 or more ED transfers within the year.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in Ontario, Canada’s largest province. Ontario has a population of approximately 13 million people, with nearly 75,000 living in a NH at any given point in time. NHs are residential settings that provide access to 24-h care for adults unable to live safely in community settings. Most NH beds are used for long-term care purposes with limited use for post-acute or rehabilitative care. In Ontario, the vast majority of individuals have publicly funded health insurance, which covers physician visits, acute care, and NH care.

Study design and data

This is a retrospective cohort study using multiple health administrative databases, including: the Continuing Care Reporting System (CCRS), the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS), the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), and the Registered Persons Database (RPDB). The CCRS is a repository of Resident Assessment Instrument – Minimum Data Set, version 2.0 (RAI-MDS 2.0) clinical assessments that are mandated for completion on all NH residents in Ontario. The RAI-MDS 2.0 includes over 300 data items on diagnoses, cognitive and physical functioning, and behaviour. NACRS is mandated for completion on all visits to EDs within the province and includes various time and date stamps, and diagnoses. The DAD consists of standardized chart abstractions of all acute care hospital stays. The RPDB contains basic demographic data, including dates of birth and death (if applicable), for all provincial residents with valid health insurance. These datasets were linked using encoded identifiers and analyzed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES).

Ethics

ICES is a prescribed entity under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. Section 45 authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to or planning for all or part of the health system. Projects conducted under section 45, by definition, do not require review by a Research Ethics Board. This project was conducted under section 45 and approved by ICES’ Privacy and Compliance Office. The study received approval from the Research Ethics Board at Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada.

Cohort identification and follow-up

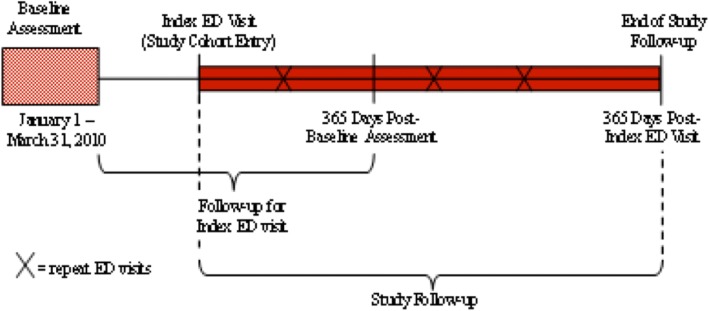

We identified all individuals who resided in a NH in Ontario between January 1 and March 31, 2010, using the first RAI-MDS assessment (if more than one) from this period as baseline. We excluded residents younger than age 65 years (n = 4868) since they have different health needs which may influence their use of acute care services. We further excluded individuals who were not Ontario residents (139), had invalid unique identifiers (26), or resided in a NH with fewer than 25 beds (323). This left a total of 71,766 residents. From baseline, residents were followed to their first ED visit (the “index” visit) or the end of 365 days, whichever came first. We identified 25,897 residents in 604 NHs who had an index ED visit within one year of baseline. Of this group, 246 (0.9%) died during the index ED visit and were excluded from further analyses. The final cohort consisted of 25,653 individual residents who were discharged alive from an index ED visit. This cohort was followed from the date of the index ED visit until the first of: discharge from the LTC home, death, or 365 days from the index ED visit. All subsequent ED transfers and acute care hospital admissions within the follow-up year were counted and treated as risk-free periods. See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Cohort development and timeline

Resident characteristics

All variables used to describe residents were obtained from the baseline RAI-MDS 2.0 assessment. This included age, sex, length of stay in the NH at baseline, clinical conditions, cognition, physical functioning, and behaviour. Cognition was measured using the embedded Cognitive Performance Scale [13]. Physical functioning was assessed on the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Short-Form Scale [14]. We also included the Changes in Health and End-Stage Signs and Symptoms (CHESS) Scale as a measure of clinical instability [15]. To estimate multimorbidity, we summed clinical conditions. As a sensitivity analysis, we assessed for changes in resident characteristics from baseline to subsequent RAI-MDS 2.0 assessments but found little change.

Emergency department visits

We identified all unscheduled ED visits that occurred between the index ED visit and the end of the follow-up period. ED visits were described according to diagnosis, type, timing, and discharge disposition. All visits were classified into one of five mutually exclusive categories based on diagnosis to obtain visit type, as defined in our earlier work [1, 16]. These were: potentially preventable (visits which may have been avoided had a pre-existing condition been better managed earlier, comparable to ambulatory care sensitive conditions), fall-related injury, non-fall injury, low acuity (visits that were triaged as non-urgent and ended with the resident returning to the LTC home), and other (visits that did not fit in any of the other categories). The timing of each visit was defined according to the day of week and time of day (weekday, weeknight, weekend-day, and weekend-night) recorded at triage. Discharge disposition captured the resident’s discharge location and included admission to hospital, death within the ED, and return to the NH.

All visits, except for the index ED visit, were also characterized by the number of days since discharge from the preceding ED visit and categorized as: immediate (within 72 h of discharge from the preceding ED visit), short-term (within 3–10 days), long-term (within 11–90 days), and distant (91 or more days), as adapted from Weiss and colleagues [5]. We also looked to see if visits were concordant on type with the ED visit immediately preceding it.

Frequent ED visitors

We identified a subset of residents who could be described as “frequent ED visitors”. To be consistent with the research on non-NH populations, these were defined as residents who had 4 visits within one year (in this case, those with 3 repeat ED visits) [6].

Analyses

We characterized the cohort according to baseline demographic, clinical, and functional characteristics, as well as the index ED visit. We counted all subsequent (repeat) ED visits and categorized as one of: second, third, fourth, or fifth or later visits; we used descriptive statistics to fully characterize all repeat ED visits.

We followed a series of steps to identify risk factors for repeat ED visits. First, we performed bivariate statistical analyses to compare residents who did and did not experience any repeat ED visits on baseline characteristics and index ED visit characteristics. We then used logistic regression to identify risk factors for making at least one repeat ED visit. We modeled a multinomial outcome: any repeat ED visit, death without a repeat ED visit, and no repeat ED visit or death (the reference category). Each variable that significantly differed on bivariate comparisons was tested in the multinomial logistic regression. Any variable that did not reach a significance level of p < 0.05 was removed from the model. Next, we used an Andersen-Gill (A-G) model to estimate the effect of identified risk factors on the rate of repeat ED visits [17]. The A-G model is a generalization of the Cox proportional hazards model extended for recurrent outcome events and is recommended based on its efficiency and power [18, 19]. In this model, the dependent (outcome) variable is the rate of repeat ED visits measured as the time between visits counted over the follow-up period. The model provides maximum likelihood estimates of a relative rate (RR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each independent variable (in this case, the risk factors selected from the logistic regression models). The RR quantifies the change in the repeat ED visit rate relative to a baseline rate. Other benefits of this model include its ability to account for risk-free time (for example, when a resident is in the ED), clustering in NHs, and competing risks (specifically death).

Frequent visitors, those who experienced 3 or more repeat ED visits, were compared to all other residents in the cohort on baseline characteristics. Multinomial logistic regression was used to identify risk factors for being a frequent ED visitor. The model outcomes were: 3 or more repeat ED visits, death, or fewer than 3 repeat ED visits (reference). Risk factors were identified in a step-wise fashion by first testing variables in bivariate analyses, then added in categories to a single model, then a full model, and finally a reduced model based on associations identified as significant at p < 0.05. Repeat ED visits among frequent visitors were described in a manner similar to that for the full cohort.

All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4.3 except for the A-G model which was conducted in Rstudio version 0.98.1091.

Results

The cohort

Among our cohort of 25,653 residents, 12,505 (48.8%) made a total of 24,389 repeat ED visits during the follow-up year. Of residents with repeat ED visits, 6604 (52.8%) made one, 3042 (24.3%) made two, 1425 (11.4%) made three, and the remainder made four or more. A total of 10,310 residents died within the one-year follow-up.

The cohort’s mean (SD) age was 84.5 (7.5) years, 68.2% were female, and 67.9% had been in the NH for one year or longer (Table 1). Fifty-four percent experienced moderate or severe cognitive impairment, and 85.0% experienced moderate to full ADL dependence. The most common reported clinical conditions were non-Alzheimer’s dementias (42.4%), depression (28.3%), diabetes (28.2%), and stroke (22.2%). The majority had more than one chronic condition.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of study cohort at baseline

| Full cohort N = 25,653 |

No repeat ED visit during follow-up N = 13,148 |

At Least 1 repeat ED visit during follow-up N = 12,505 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, n (%) | |||

| 65–74 | 2782 (10.8%) | 1233 (9.4%) | 1549 (12.4%) |

| 75–84 | 9075 (35.4%) | 4408 (33.5%) | 4667 (37.3%) |

| 85–94 | 11,784 (45.9%) | 6284 (47.8%) | 5500 (44.0%) |

| 95+ | 2012 (7.8%) | 1223 (9.3%) | 789 (6.3%) |

| Women, n (%) | 17,504 (68.2%) | 9238 (70.3%) | 8266 (66.1%) |

| Length of Stay in Nursing Home, n (%) | |||

| < 30 days | 775 (3.0%) | 318 (2.4%) | 457 (3.7%) |

| 30–89 days | 1250 (4.9%) | 565 (4.3%) | 685 (5.5%) |

| 90–364 days | 6214 (24.2%) | 2904 (22.1%) | 3310 (26.5%) |

| 365 or more days | 17,414 (67.9%) | 9361 (71.2%) | 8053 (64.4%) |

| Cognitive Impairment, n (%) | |||

| Minimal | 11,851 (46.2%) | 5602 (42.6%) | 6249 (50.0%) |

| Moderate | 9013 (35.1%) | 4784 (36.4%) | 4229 (33.8%) |

| Severe | 4789 (18.7%) | 2762 (21.0%) | 2027 (16.2%) |

| Activities of Daily Living Impairment, n (%) | |||

| Minimal | 3842 (15.0%) | 1817 (13.8%) | 2025 (16.2%) |

| Moderate | 10,785 (42.0%) | 5217 (39.7%) | 5568 (44.5%) |

| Dependent | 11,026 (43.0%) | 6114 (46.5%) | 4912 (39.3%) |

| Problem Behaviours, n (%) | |||

| Inappropriate | 4337 (16.9%) | 2344 (17.8%) | 1993 (15.9%) |

| Verbally abusive | 4954 (19.3%) | 2590 (19.7%) | 2364 (18.9%) |

| Physically abusive | 2859 (11.1%) | 1568 (11.9%) | 1291 (10.3%) |

| Wanderer | 4641 (18.1%) | 2396 (18.2%) | 2245 (18.0%) |

| Resists Care | 8564 (33.4%) | 4597 (35.0%) | 3967 (31.7%) |

| CHESS Scale Score, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 11,931 (46.5%) | 5959 (45.3%) | 5972 (47.8%) |

| 1 | 8283 (32.3%) | 4299 (32.7%) | 3984 (31.9%) |

| 2 | 3920 (15.3%) | 2039 (15.5%) | 1881 (15.0%) |

| 3 | 1140 (4.4%) | 621 (4.7%) | 519 (4.2%) |

| 4 or 5 | 379 (1.5%) | 230 (1.8%) | 149 (1.1%) |

| Diagnoses, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 7231 (28.2%) | 3393 (25.8%) | 3838 (30.7%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 4346 (16.9%) | 2045 (15.6%) | 2301 (18.4%) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 4526 (17.6%) | 2516 (19.1%) | 2010 (16.1%) |

| Other dementia | 10,873 (42.4%) | 5793 (44.1%) | 5080 (40.6%) |

| Stroke | 5696 (22.2%) | 2785 (21.2%) | 2911 (23.3%) |

| Depression | 7269 (28.3%) | 3751 (28.5%) | 3518 (28.1%) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 4870 (19.0%) | 2305 (17.5%) | 2565 (20.5%) |

| Cancer | 2477 (9.7%) | 1288 (9.8%) | 1189 (9.5%) |

| Renal Failure | 3117 (12.2%) | 1388 (10.6%) | 1729 (13.8%) |

| Number of chronic conditions, n (%) | |||

| 0 or 1 | 3292 (12.8%) | 1725 (13.1%) | 1567 (12.5%) |

| 2 | 5601 (21.8%) | 2934 (22.3%) | 2667 (21.3%) |

| 3 | 6346 (24.7%) | 3289 (25.0%) | 3057 (24.4%) |

| 4 | 4965 (19.4%) | 2524 (19.2%) | 2441 (19.5%) |

| 5+ | 5449 (21.2%) | 2676 (20.4%) | 2773 (22.2%) |

| Fell in prior 30 days, n (%) | 4044 (15.8%) | 2035 (15.5%) | 2009 (16.1%) |

Emergency department visits

Index and repeat ED visits are described in Table 2. Of index ED visits, 25.3% were identified as potentially preventable, 20.0% as a fall-related injury, and 45.8% as other. At the end of the index ED visit, 56.5% of residents returned to their LTC home and 43.5% were admitted to hospital; those admitted to hospital had an average stay of 6.7 (8.4) days. Following the index visit, 19.1% died without subsequent ED use.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of index emergency department visit and subsequent repeat visits over one year

| Visit Descriptors | Index ED visit | 1st Repeat Visit | 2nd Repeat Visit | 3rd Repeat Visit | 4th Repeat Visit | 5th and subsequent repeat visits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 25,653 | N = 12,505 | N = 5901 | N = 2859 | N = 1434 | N = 1690 | |

| Type of ED visit, n (%) | ||||||

| Potentially preventable | 6479 (25.3%) | 3380 (27.0%) | 1697 (28.8%) | 821 (28.7%) | 422 (29.4%) | 486 (28.8%) |

| Fall-related injury | 5119 (20.0%) | 1872 (15.0%) | 723 (12.3%) | 314 (11.0%) | 138 (9.6%) | 93 (5.5%) |

| Non-fall injury | 829 (3.2%) | 324 (2.6%) | 125 (2.1%) | 49 (1.7%) | 18 (1.3%) | 32 (1.9%) |

| Low Acuity | 1458 (5.7%) | 758 (6.1%) | 297 (5.0%) | 146 (5.1%) | 79 (5.5%) | 91 (5.4%) |

| Other | 11,768 (45.9%) | 6171 (49.3%) | 3059 (51.8%) | 1529 (53.5%) | 777 (54.2%) | 988 (58.5%) |

| Same ED Visit type as visit immediately preceding, n (%) | N/A | 5452 (43.6%) | 2556 (43.3%) | 1497 (52.4%) | 777 (54.2%) | 1002 (59.3%) |

| Timing of ED visit relative to visit immediately preceding | ||||||

| Immediate (< 3 days) | N/A | 641 (5.1%) | 371 (6.3%) | 182 (6.4%) | 102 (7.1%) | 165 (9.8%) |

| Short-term (3-10 days) | N/A | 1449 (11.6%) | 830 (14.1%) | 488 (17.1%) | 253 (17.6%) | 367 (21.7%) |

| Long-term (11-90 days) | N/A | 5039 (40.3%) | 2895 (49.1%) | 1537 (53.8%) | 816 (56.9%) | 970 (57.4%) |

| Distant (> 90 days) | N/A | 5376 (43.0%) | 1805 (30.6%) | 652 (22.8%) | 263 (18.3%) | 188 (11.1%) |

| ED Visit disposition, N (%) | ||||||

| Admitted to hospital | 11,163 (43.5%) | 5657 (45.2%) | 2762 (46.8%) | 1318 (46.1%) | 660 (46.0%) | 709 (42.0%) |

| Died in ED | 0 (0.0%) | 100 (0.8%) | 63 (1.1%) | 22 (0.8%) | 10 (0.7%) | 12 (0.7%) |

| Returned to LTC | 14,490 (56.5%) | 6748 (54.0%) | 3076 (52.1%) | 1519 (53.1%) | 764 (53.3%) | 969 (57.3%) |

| Days in hospital among those admitted | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 6.71 ± 8.44 | 7.18 ± 8.69 | 7.95 ± 14.16 | 7.27 ± 8.45 | 8.78 ± 19.07 | 8.16 ± 16.36 |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (3–8) | 5 (3–9) | 5 (3–9) | 5 (3–9) | 6 (3–10) | 5 (2–9) |

| Died without making another ED Visit, n (%) | 4899 (19.1%) | 4139 (33.1%) | 1957 (33.2%) | 969 (33.9%) | 464 (32.4%) | 514 (30.4%) |

Among first and second repeat ED visits, 43% were of the same type as the preceding visit, and concordance increased with subsequent ED visits. Of first repeat ED visits, 5.1% were immediate, 11.6% were short-term, 40.3% were long-term, and 43.0% were distant relative to the index ED visit. For later repeat ED visits, immediate, short-term, and long-term visit intervals became more frequent while distant intervals became less frequent. While the frequency of hospital admission changed little with successive repeat visits, the length of hospital stay among those admitted increased to an average of 8.2 (16.4) days and the proportion who died following the visit increased to over 30%. We looked at visit patterns stratified by index ED visit type but found little difference compared to the overall patterns (data not shown).

Risk factors for repeat ED visits

Differences between residents who did and did not have at least one repeat ED visit were generally small (Table 1). Residents who made at least one repeat visit tended to be slightly younger, and have minimal cognitive impairment and ADL dependence than residents without repeat ED visits. There were also small differences across a number of diagnoses.

Results of both models to identify risk factors for repeat ED use are shown in Table 3. From the multinomial logistic regression, residents who were male, had moderate ADL dependence, any medical instability, diabetes, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, or dysrhythmia had a greater odds of making at least one repeat ED visit. Residents with longer lengths of stay, severe cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, or 5 or more chronic conditions had a lower odds of making a repeat ED visit. There was no association with age; other variables, including fall history and specific diagnoses, were excluded from the final model. The complementary results on death from this multinomial logistic regression model are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Table 3.

Final logistic regression and Andersen-Gill regression model results to identify risk factors for any repeat ED visit and more frequent repeat ED visits, respectively

| Logistic regression | Andersen-Gill regression | |

|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% Confidence interval) | Incidence rate Ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

| Age | ||

| 65–74 | REF | REF |

| 75–84 | 1.01 (0.91–1.11) |

1.03 (0.99–1.07) |

| 85–94 | 1.00 (0.88–1.06) |

1.05 (1.01–1.10) |

| 95 and older | 0.91 (0.79–1.04) |

1.17 (1.10–1.25) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | REF | REF |

| Male | 1.27 (1.19–1.36) |

1.20 (1.17–1.24) |

| Length of stay in LTC | ||

| < 30 days | REF | REF |

| 30–89 days | 0.71 (0.56–0.89) |

0.90 (0.83–0.97) |

| 90–364 days | 0.60 (0.49–0.73) |

0.78 (0.73–0.83) |

| 365 or more days | 0.45 (0.38–0.57) |

0.71 (0.67–0.76) |

| Cognitive impairment | ||

| Minimal | REF | REF |

| Moderate | 0.92 (0.86–1.01) |

0.98 (0.95–1.01) |

| Severe | 0.92 (0.84–0.99) |

1.03 (0.99–1.07) |

| ADL dependence | ||

| Minimal | REF | REF |

| Moderate | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) |

1.08 (1.04–1.13) |

| Dependent | 1.07 (0.98–1.18) |

1.23 (1.18–1.28) |

| CHESS scale score | ||

| 0 | REF | REF |

| 1 | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) |

1.10 (1.06–1.13) |

| 2 | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) |

1.17 (1.13–1.21) |

| 3 | 1.19 (1.02–1.39) |

1.24 (1.16–1.31) |

| 4 or 5 | 1.10 (0.83–1.44) |

1.23 (1.11–1.37) |

| Diagnoses | ||

| Diabetes | 1.28 (1.19–1.37) |

1.13 (1.10–1.16) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.26 (1.16–1.37) |

1.14 (1.10–1.18) |

| Arthritis | 0.93 (0.87–1.00) |

0.93 (0.90–0.95) |

| Alzheimer’s disease or Other Dementia | 0.93 (0.86–1.00) |

0.95 (0.92–0.98) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.26 (1.17–1.37) |

1.11 (1.07–1.14) |

| Liver disease | – | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) |

| Renal failure | 1.35 (1.23–1.49) |

1.16 (1.12–1.20) |

| Dysrhythmia | 1.14 (1.03–1.27) |

– |

| Cancer | 1.06 (0.95–1.17) |

– |

| Number of chronic conditions | ||

| 0 or 1 | REF | REF |

| 2 | 0.95 (0.85–1.05) |

0.99 (0.95–1.04) |

| 3 | 0.90 (0.81–1.01) |

0.96 (0.92–1.01) |

| 4 | 0.88 (0.78–1.00) |

0.95 (0.90–1.00) |

| 5 or more | 0.82 (0.71–0.95) |

0.94 (0.89–0.99) |

| Fell in prior 30 days | – | 0.95 (0.92–0.98) |

The A-G regression was used to model the rate of repeat ED visits. Preliminary modeling (not shown) did not indicate excess individual level heterogeneity in the number of repeat ED visits. Consistent with the results of the logistic regression, a higher rate of repeat ED visits was associated with being male, ADL dependence, medical instability, and specific diagnoses (diabetes, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and liver failure). Also consistent, residents with longer lengths of stay, Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, and 5 or more chronic conditions had a lower relative rate of repeat ED visits. Unlike the logistic regression model, older age was associated with an increased rate of repeat ED visits while a prior fall was associated with a decreased rate. Neither cognitive impairment nor ADL dependence was associated with repeat ED visit rate.

Frequent ED visitors

A total of 2859 (11.1%) residents were identified as frequent ED visitors (Table 4). Overall, frequent ED visitors tended to be younger, male, had shorter lengths of stay in the NH, to have minimal cognitive impairment and be independent in ADL function, and less likely to exhibit problem behaviours. Frequent ED visitors were more likely to have diabetes, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and renal failure but less likely to have Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. In the final logistic regression model, similar patterns emerged. Notably, those who were older, had longer lengths of stay, or a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia had lower odds of being a frequent ED visitor, while residents who were male or had specific diagnoses (diabetes congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, or liver disease) had greater odds of being a frequent ED user. No associations with cognitive impairment, ADL function, medical instability, number of chronic conditions, or behaviours were observed in the final model. We did find that residents whose index ED visit was for an injury (either fall or non-fall related) had reduced odds of being a frequent ED visitor. The results on death from this multinomial model are presented in Additional file 1: Table S2.

Table 4.

Characteristics of frequent emergency department visitors (3 or more repeat ED visits) relative to non-frequent ED visitors and results of the logistic regression model to identify risk factors

| Non-Frequent ED visitors N – 22,794 |

Frequent ED visitors N = 2859 |

Adjusted Odds ratio (95% Confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, n (%) | |||

| 65–74 | 2306 (10.1%) | 476 (16.6%) | REF |

| 75–84 | 7911 (34.7%) | 1164 (40.7%) | 0.90 (0.80–1.02) |

| 85–94 | 10,696 (46.9%) | 1088 (38.1%) | 0.76 (0.67–0.87) |

| 95 or older | 1881 (8.3%) | 131 (4.6%) | 0.70 (0.57–0.88) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 15,703 (68.9%) | 1801 (63.0%) | REF |

| Male | 7091 (31.1%) | 1058 (37.0%) | 1.25 (1.14–1.37) |

| Length of stay in LTC, (%) | |||

| < 30 days | 649 (2.8%) | 126 (4.4%) | REF |

| 30–89 days | 1031 (4.5%) | 219 (7.7%) | 0.96 (0.74–1.26) |

| 90–364 days | 5363 (23.5%) | 851 (29.8%) | 0.69 (0.55–0.86) |

| 365 or more days | 15,751 (69.1%) | 1663 (58.2%) | 0.51 (0.41–0.63) |

| Cognitive impairment, n (%) | |||

| Minimal | 10,246 (45.0%) | 1605 (56.1%) | REF |

| Moderate | 8140 (35.7%) | 873 (30.5%) | 0.92 (0.83–1.02) |

| Severe | 4408 (19.3%) | 381 (13.3%) | 0.94 (0.81–1.10) |

| ADL Dependence, n (%) | |||

| Minimal | 3324 (14.6%) | 518 (18.1%) | REF |

| Moderate | 9504 (41.7%) | 1281 (44.8%) | 1.08 (0.96–1.22) |

| Dependent | 9966 (43.7%) | 1060 (37.1%) | 1.05 (0.92–1.20) |

| Behaviours, n (%) | |||

| Inappropriate behaviour | 3933 (17.3%) | 404 (14.1%) | 0.90 (0.79–1.03) |

| Verbally abusive | 4431 (19.4%) | 523 (18.3%) | 1.11 (0.98–1.26) |

| Physically abusive | 2618 (11.5%) | 241 (8.4%) | 0.92 (0.77–1.09) |

| Wandering | 4216 (18.5%) | 425 (14.9%) | 0.91 (0.80–1.04) |

| Resists care | 7734 (33.9%) | 830 (29.0%) | 0.99 (0.89–1.10) |

| CHESS Scale Score, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 10,552 (46.3%) | 1379 (48.2%) | REF |

| 1 | 7400 (32.5%) | 883 (30.9%) | 1.03 (0.94–1.13) |

| 2 | 3470 (15.2%) | 450 (15.7%) | 1.20 (1.06–1.35) |

| 3 | 1031 (4.5%) | 109 (3.8%) | 1.18 (0.95–1.48) |

| 4 or 5 | 341 (1.5%) | 38 (1.3%) | 1.27 (0.87–1.85) |

| Diagnoses, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 6220 (27.3%) | 1011 (35.4%) | 1.28 (1.16–1.42) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 3725 (16.3%) | 621 (21.7%) | 1.40 (1.24–1.57) |

| Arthritis | 9640 (42.3%) | 1146 (40.1%) | 0.90 (0.82–1.00) |

| Osteoporosis | 6554 (28.8%) | 714 (25.0%) | 0.92 (0.83–1.03) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 4159 (18.3%) | 367 (12.8%) | 0.83 (0.74–0.92) |

| Other dementias | 9845 (43.2%) | 1028 (36.0%) | -* |

| Stroke | 5026 (22.0%) | 670 (23.4%) | – |

| Anxiety disorder | 254 (8.9%) | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) | |

| Depression | 6474 (28.4%) | 795 (27.8%) | 0.95 (0.85–1.05) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4201 (18.4%) | 669 (23.4%) | 1.25 (1.12–1.40) |

| Cancer | 2216 (9.7%) | 261 (9.1%) | 1.06 (0.91–1.23) |

| Renal Failure | 2644 (11.6%) | 473 (16.5%) | 1.38 (1.22–1.57) |

| Liver disease | 1.35 (0.95–1.92) | ||

| Number of chronic conditions, n (%) | |||

| 0 or 1 | 2919 (12.8%) | 373 (13.0%) | REF |

| 2 | 5000 (21.9%) | 601 (21.0%) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) |

| 3 | 5675 (24.9%) | 671 (23.5%) | 0.92 (0.78–1.09) |

| 4 | 4455 (19.5%) | 510 (17.8%) | 0.82 (0.68–1.00) |

| 5 or more | 4745 (20.8%) | 704 (24.6%) | 0.92 (0.73–1.16) |

| Index Visit Type, n (%) | |||

| Potentially preventable | REF | ||

| Fall-related injury | 0.66 (0.57–0.75) | ||

| Non-fall injury | 0.75 (0.59–0.97) | ||

| Low acuity | 0.95 (0.80–1.14) | ||

| Other | 0.97 (0.87–1.07) | ||

*a single variable for Alzheimer's disease or other dementias was used in the logistic regression model

Discussion

In our comprehensive, population-based cohort study, we found that repeated transfers to the ED were common among NH residents. Within one year, nearly half of residents returned to the ED at least once, and 11% returned 3 or more times. We found that 40–60% of return visits were for reasons similar to the preceding visit and that the majority occurred at least 10 days after the prior visit. At the end of each visit, more than half of residents were discharged back to their NH and the proportion who died following a visit nearly doubled over time.

Our data show that there were generally small differences between residents who did and did not experience repeat ED visits. Overall, these groups were fairly similar with only slight differences in age, sex, chronic conditions, fall history, and behaviours, with more noticeable differences on specific diagnoses and cognitive and physical impairment. Following extensive modeling, certain characteristics emerged as risk factors but no single variable (or group of variables) were strongly predictive. Notably, those who were male and were clinically unstable, as measured by the CHESS scale, had a higher likelihood of repeat ED visits. These findings suggest what might be expected – that those residents with greater, and potentially more complex, medical need are more likely to have frequent encounters with acute care. Taken with the increased frequency of death following a greater number of ED visits, it is also possible that residents were more likely to experience repeat transfers as they approached end-of-life. In context with the rest of our findings, though, this appears to be only part of the story.

We also found that 11% of residents met the criteria for being a frequent ED visitor (3 or more repeat ED visits). Similar to what has been observed in the non-LTC population, we found that a small group (estimated at 4% of all residents aged 65 or older) accounted for a large share of repeat ED use. These residents were more likely to be younger than 75, male, have relatively shorter lengths of stay, and have minimal cognitive impairment. They were also more likely to be diagnosed with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and renal failure but less likely to have Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. Many of these same variables, notably length of stay and the diagnoses, were also associated with a greater rate of repeat ED visits. This group of frequent ED visitors is very different from the general picture of LTC residents who are most frequently characterized as very old, female, and cognitively impaired due to dementia [20, 21]. To date, there is little data to describe this subgroup and how they differ from the larger population of residents or why they are so frequently transferred to the ED.

We used two approaches to identify risk factors for repeat ED visits. While these two approaches generally revealed consistent results, others were quite different. This is not unexpected given that one approach identified risk factors associated with the likelihood of at least one repeat ED visit (logistic regression) while the other identified risk factors associated with the rate of repeat ED visits (Andersen-Gill regression). These divergent findings also may reflect the heterogeneity among NH residents at risk for experiencing repeat ED visits – and, potentially, different patterns of repeat ED visits. Our data suggests at least two groups of residents at risk for repeat ED visits – those who are medically complex (possibly approaching the end of life) and those who are younger without cognitive impairment. A better understanding of these subgroups and their needs is critical to the successful implementation of interventions to safely reduce ED transfers and improve NH care.

This study has a number of limitations. First, we included only residents over age 65 since these residents tend to differ from others [22]. We found, however, that frequent ED use was most common among residents 65–74 years, an age group typically considered “young” in NH settings. This raises questions about the needs of the 65–74 age group and whether they may be more reflective of even younger residents, who may age within NHs, than older residents who tend to enter at later stages of illness. Second, despite the breadth of data, we had very little information on the factors immediately preceding an ED transfer, such as acute changes, family and resident preferences, or how a prior transfer influences subsequent transfer. Our study offers a broad overview of the problem of repeat ED transfers but additional research is required to explore the immediate details. Third, we used data from a single jurisdiction and it is difficult to know how generalizable our findings are to other jurisdictions given how little available data there is on repeat ED visits. Given that NH populations are fairly similar across jurisdictions and ED transfers are common, we anticipate that our overall trends are generalizable but the individual risk factors may differ. Finally, this research focuses solely on resident characteristics and does not include information on either the NH or the treating ED. Given that this is among the first studies to explore repeat ED transfers, we intentionally focused on residents; however, it is clear from other research that facility characteristics do influence resident outcomes, including acute care use [16, 23].

Conclusions

In this study of over 25,000 NH residents, we found nearly half made at least one repeat ED and 11% made at least three repeat ED visits. There were subtle differences between residents who did and did not experience repeat visits but our findings suggest that medically complex residents and younger residents without cognitive impairment are at risk for such outcomes. Reducing ED use, especially repeated use, will require a better understanding of these resident groups and how to best meet their needs within the NH environment.

Additional file

Multinomial Model Results for DeathG (DOCX 25 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dilzayn Panjwani for her assistance in coordinating the study team.

Funding

This study was supported by an operating grant (“Repeat Emergency Department Visits Among Long-Term Care Residents in Ontario” FRN#123315) from the Institute of Health Services and Policy Research at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Dr. Gruneir is supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award. Dr. Rochon holds the Retired Teachers of Ontario (RTO/ERO) Chair in Geriatric Medicine at the University of Toronto. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of the material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in the material are those of the authors and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the program may rely on coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES.

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activities of Daily Living

- A-G model

Andersen-Gill regression model

- CCRS

Continuing Care Reporting System

- CHESS

Changes in Health and End-Stage Signs and Symptoms

- DAD

Discharge Abstract Database

- ED

Emergency department

- ICES

Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

- NACRS

National Ambulatory Care Reporting System

- NH

Nursing home

- RAI-MDS 2.

Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Data Set version 2.0

- RPDB

Registered Persons Database

Authors’ contributions

AG conceptualized and designed the study, oversaw data analysis and interpretation, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CC designed the statistical analysis, wrote the statistical code, contributed to interpretation of the data, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. XW and AN each contributed to statistical design, conducted significant portions of the data analysis, and provided critical feedback on manuscript drafts. SEB, GMA, and PAR each helped to conceptualize the study, contributed to data interpretation, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

ICES is a prescribed entity under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. Section 45 authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to or planning for all or part of the health system. Projects conducted under section 45, by definition, do not require review by a Research Ethics Board. This project was conducted under section 45 and approved by ICES’ Privacy and Compliance Office. The study received approval from the Research Ethics Board at Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Canada.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12877-018-0854-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Andrea Gruneir, Email: Gruneir@ualberta.ca.

Candemir Cigsar, Email: ccigsar@mun.ca.

Xuesong Wang, Email: Xuesong.wang@ices.on.ca.

Alice Newman, Email: griftana@gmail.com.

Susan E. Bronskill, Email: Susan.bronskill@ices.on.ca

Geoff M. Anderson, Email: Geoff.anderson@utoronto.ca

Paula A. Rochon, Email: paula.rochon@wchospital.ca

References

- 1.Gruneir A, Bell CM, Bronskill SE, Schull M, Anderson GM, Rochon PA. Frequency and pattern of emergency department visits by long-term care residents-a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(3):510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergman H, Clarfield AM. Appropriateness of patient transfer from a nursing home to an acute-care hospital: a study of emergency room visits and hospital admissions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(12):1164–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb03568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerr HD, Byrd JC. Nursing home patients transferred by ambulance to a VA emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):132–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke RE, Rooks SP, Levy C, Schwartz R, Ginde AA. Identifying potentially preventable emergency department visits by nursing home residents in the United States. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(5):395–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.01.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss SJ, Ernst AA, Miller P, Russell S. Repeat EMS transports among elderly emergency department patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6(1):6–10. doi: 10.1080/10903120290938698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaCalle E, Rabin E. Frequent users of emergency departments: the myths, the data, and the policy implications. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernstein SL. Frequent emergency department visitors: the end of inappropriateness. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(1):18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuda KK, Immekus R. Frequent users of Massachusetts emergency departments: a statewide analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrén KG, Rosenqvist U. Heavy users of an emergency department: psycho-social and medical characteristics, other health care contacts and the effect of a hospital social worker intervention. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21(7):761–770. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt KA, Weber EJ, Showstack JA, Colby DC, Callaham ML. Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan BTB, Ovens HJ. Frequent users of emergency departments. Do they also use family physicians' services? Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:1654–1660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowthian J, Straney LD, Brand CA, Barker AL, Smit P de V, Newnham H, et al. Unplanned early return to the emergency department by older patients: the safe elderly emergency department discharge (SEED) project. Age Ageing. 2016;45(2):255–261. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, Hawes C, Phillips C, Mor V, et al. MDS cognitive performance scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49(4):M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.M174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 1999;54(11):M546–M553. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.M546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirdes JP, Frijters DH, Teare GF. The MDS-CHESS scale: a new measure to predict mortality in institutionalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):96–100. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2002.51017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruneir A, Bronskill SE, Newman A, Bell CM, Gozdyra P, Anderson GM, et al. Variation in emergency department transfer rates from nursing homes in Ontario, Canada. Healthc Policy. 2016;12(2):76–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen PK, Gill RD. Cox's regression model for counting processes: a large sample study. Ann Stat. 2018;10(4):1100–1120. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176345976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amorim LDAF, Cai J. Modelling recurrent events: a tutorial for analysis in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(1):324–333. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy BS, Kasl SV, Vaccarino V. Repeated hospitalizations and self-rated health among the elderly: a multivariate failure time analysis. Am J Epidemiol [Internet] 2001;153(3):232–241. Available from: https://doi-org.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/10.1093/aje/153.3.232 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Estabrooks CA, Poss JW, Squires JE, Teare GF, Morgan DG, Stewart N, et al. A profile of residents in prairie nursing homes. Can J Aging Cambridge University Press. 2013;32(3):223–231. doi: 10.1017/S0714980813000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theou O, Tan ECK, Bell JS, Emery T, Robson L, Morley JE, et al. Frailty levels in residential aged care facilities measured using the frailty index and FRAIL-NH scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):e207–e212. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Persson DI, Ostwald SK. Younger residents in nursing homes. J Gerontol Nurs SLACK Incorporated; 2009 ;35(10):22–31–quiz32–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Intrator O, Castle NG, Mor V. Facility characteristics associated with hospitalization of nursing home residents: results of a national study. Med Care. 1999;37(3):228–237. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multinomial Model Results for DeathG (DOCX 25 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the program may rely on coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES.