Abstract

Purpose: Despite higher rates of modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in gay and bisexual men, few studies have examined sexual orientation differences in CVD among men. The purpose of this study was to examine sexual orientation differences in modifiable risk factors for CVD and CVD diagnoses in men.

Methods: A secondary analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2001–2012) was conducted. Multiple imputation was performed for missing values. Differences across four distinct groups were analyzed: gay-identified men, bisexual-identified men, heterosexual-identified men who have sex with men (MSM), and heterosexual-identified men who denied same-sex behavior (categorized as exclusively heterosexual). Multiple logistic regression models were run with exclusively heterosexual men as the reference group.

Results: The analytic sample consisted of 7731 men. No differences between heterosexual-identified MSM and exclusively heterosexual men were observed. Few differences in health behaviors were noted, except that, compared to exclusively heterosexual men, gay-identified men reported lower binge drinking (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.37–0.85). Bisexual-identified men had higher rates of mental distress (AOR 2.39, 95% CI = 1.46–3.90), obesity (AOR 1.69, 95% CI = 1.02–2.72), elevated blood pressure (AOR 2.30, 95% CI = 1.43–3.70), and glycosylated hemoglobin (AOR 3.01, 95% CI = 1.38–6.59) relative to exclusively heterosexual men.

Conclusions: Gay-identified and heterosexual-identified MSM demonstrated similar CVD risk to exclusively heterosexual men, whereas bisexual-identified men had elevations in several risk factors. Future directions for sexual minority health research in this area and the need for CVD and mental health screenings, particularly in bisexual-identified men, are highlighted.

Keywords: : cardiovascular disease, health promotion, mental health, sexual minorities, stress

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 In 2015, CVD accounted for 17.7 million deaths, comprising 45% of all noncommunicable disease deaths worldwide.1 In the United States, more than 30% of adult men have some form of CVD, and men account for over half of all CVD-related deaths.2 By 2035, it is estimated that 45% of all Americans will have at least one type of CVD, and direct medical costs related to CVD will more than double to $749 billion per year.3 Approximately 90% of CVD risk is attributed to modifiable risk factors, including poor mental health (such as stress and depression), tobacco use, alcohol consumption, diet, physical activity, obesity, lipids, diabetes, and hypertension.4

Although significant racial/ethnic disparities in CVD are recognized,5 little is known about the impact of sexual orientation on CVD risk in men.6 Social stressors (such as victimization and discrimination) are posited to have a deleterious effect on the health of sexual minority (gay and bisexual) men.6–8 Although mental health, substance use, and HIV/AIDS disparities are well documented in sexual minority men, there is a dearth of research examining CVD.6 A recent systematic review of CVD risk and CVD diagnoses in sexual minorities (unrelated to HIV or AIDS) detected higher rates of tobacco use and poor mental health in sexual minority men compared to heterosexual peers.9 Few studies have examined sexual orientation differences among men for other established CVD risk factors, such as diet and physical activity. Although most studies report no difference in diet quality between sexual minority and heterosexual men,10–12 a recent study found that, relative to heterosexual men, gay men had worse diet quality.13 Findings for physical activity are mixed with some studies reporting no difference,10,11,14–16 whereas others have noted higher physical activity in sexual minority men.13,17,18 Furthermore, use of certain antiretroviral medications,19–21 tobacco use,22,23 heavy drinking,24 and the physiological effects of HIV/AIDS25,26 have been posited to contribute to heightened CVD risk among people living with HIV/AIDS. As HIV/AIDS prevalence is higher among sexual minority men this has been proposed as an additional risk factor for CVD in this population.27

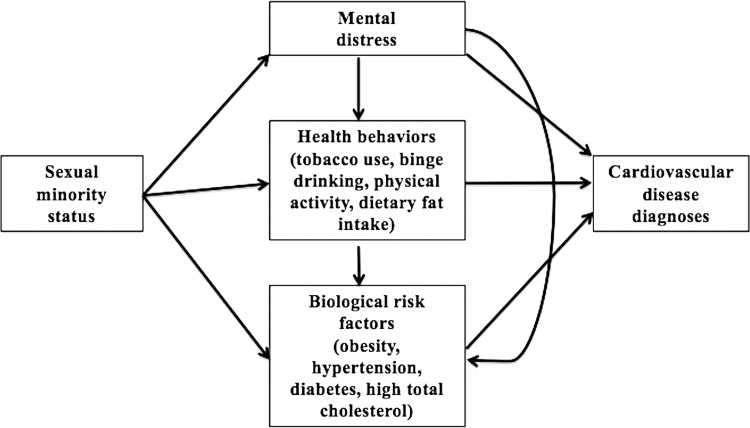

We sought to address limitations of the extant literature on CVD in sexual minority men.9,28 For instance, although stress is posited to contribute to health disparities in sexual minority men,8,29 few CVD studies include measures of stress. Stress is associated with negative health behaviors that increase CVD risk, including tobacco use, alcohol use, physical inactivity, and consumption of a high fat diet.30 Furthermore, stress is associated with excess CVD risk through mediated biological pathways.31–33 In addition, despite evidence of the link between stress and biological risk factors for CVD, only five studies in the aforementioned systematic review used biomarkers to assess sexual orientation differences in CVD risk among men.9 Thus, the present study was informed by the biobehavioral interaction model.34 Figure 1 shows hypothesized associations among sexual minority status, modifiable risk factors for CVD, and CVD diagnoses. We hypothesized that gay- and bisexual-identified men would report higher mental distress,8 which in turn would be associated with increased negative health behaviors,30 and biological risk factors for CVD (such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and high total cholesterol34) compared to exclusively heterosexual men. Therefore, the purpose of this study, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (2001–2012), was to examine sexual orientation differences in modifiable risk factors for CVD (including perceived mental distress, health behaviors, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and high total cholesterol) and CVD diagnoses.

FIG. 1.

Conceptual model.

Methods

NHANES is a national survey of cross-sectional data that is used to monitor the health of Americans.35 NHANES is the largest national survey that includes information about sexual orientation and the biomarkers of interest for this study. A complex multistage probability sampling design is used to permit representative sampling of individuals across the United States.35 Data are collected through home interviews followed by a standardized physical examination (that includes blood pressure measurement and collection of biological samples) performed by trained medical professionals.36 The Institutional Review Board of New York University deemed this study exempt because NHANES data are publicly available. NHANES data from 2001 to 2012 were selected because these data cycles included a measure of mental distress that was not included in the 2013–2014 release.

Sample size

Inclusion criteria: Sexual orientation can be defined by sexual identity, sexual behavior, and sexual attraction.37 NHANES does not include data on sexual attraction. Sexual identity and sexual behavior are only assessed in participants between 18 and 59 years old. Male participants who reported their sexual identity as “heterosexual or straight,” “homosexual or gay,” or “bisexual” were categorized as “heterosexual,” “gay identified,” or “bisexual identified,” respectively. We used the sexual behavior item to further divide heterosexual men into two groups as follows: heterosexual-identified men who have sex with men (MSM) and exclusively heterosexual men. Men who identified as heterosexual but who reported having at least one lifetime male sexual partner were included in a separate category as heterosexual-identified MSM. Heterosexual men who denied any sexual behavior with men were categorized as exclusively heterosexual.

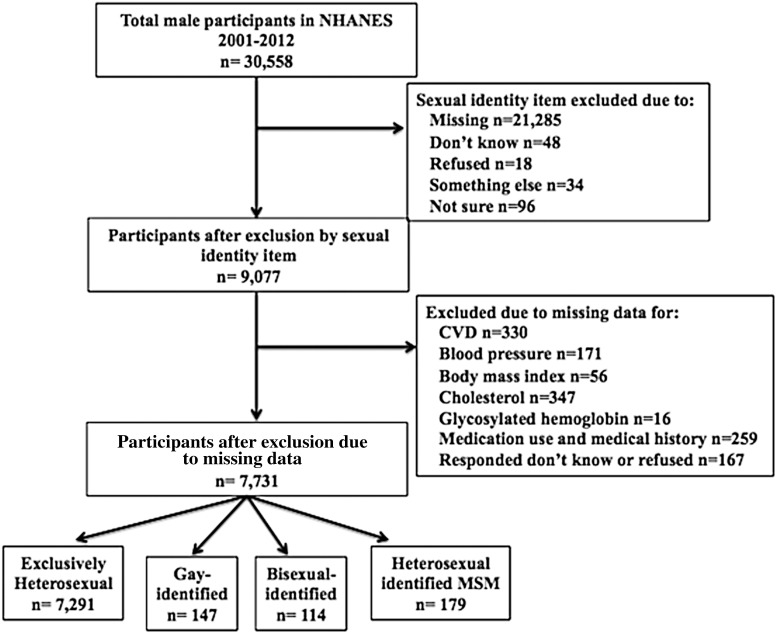

Exclusion criteria: Due to small sample sizes we excluded participants who identified their sexual identity as “don't know (n = 48),” “refused (n = 18),” “something else (n = 34),” or “not sure (n = 96).” Participants with missing data for sexual identity, blood pressure, glycosylated hemoglobin, total cholesterol, body mass index (BMI), medication use and medical history, and CVD diagnoses or who answered “don't know” or “refused” for any of the study variables were also excluded.

Measures

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation was measured using sexual identity and sexual behavior. Sexual identity was measured with the item: “Do you think of yourself as heterosexual or straight, homosexual or gay, bisexual, something else, or not sure?” Sexual behavior was used to further divide heterosexual-identified men into exclusively heterosexual men and heterosexual-identified MSM participants as described above.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Age (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other race), income (family income to poverty ratio), education (less than high school education, high school, some college, or college graduate or above), and marital status (married/partnered, widowed, divorced, separated, or single) were included as demographic characteristics. The measure of income used, the family income to poverty ratio (range 0–5), was provided by NHANES and was determined by dividing the total household income by the poverty threshold as determined by the Federal Register for that specific survey year. A higher family income to poverty ratio indicates higher socioeconomic status. Family history of CVD was defined as having a blood relative with a history of angina, heart attack, or stroke before the age of 50. As participants were not asked to self-report their HIV status, HIV status was determined by HIV antibody blood assay that was a component of the physical examination in NHANES. Report of health insurance coverage in the past year was also included.

Modifiable risk factors

A measure of nonspecific stress from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) Health-Related Quality of Life-4 included in NHANES was used: “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” As recommended, participants who reported 14 or more days of mental distress were considered to have frequent mental distress.38 Health behaviors included tobacco use, binge drinking, physical activity, and dietary fat intake. Current tobacco use was examined by asking participants: “Do you now smoke?” Current tobacco use was dichotomized and coded as “Yes” (1) if participants responded that they currently smoked every day or some days and “No” (0) if they did not. Binge drinking was established based on report of binge drinking (five or more alcohol drinks on the same occasion) in the past 12 months.39 Physical activity in the past week was assessed using self-report to determine whether participants met physical activity recommendations for adults (≥150 minutes of moderate-intensity or ≥75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week or equal amount of both).40 The polyunsaturated fatty acid and monounsaturated fatty acid to saturated fatty acid ratio in the past 24 hours was obtained from the NHANES dietary interview. We then dichotomized dietary fat intake based on the Healthy Eating Index 2010, which classifies a ratio of unsaturated to saturated fat ≥2.5 as adequate.41

Additional risk factors included obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and high total cholesterol. BMI (kg/m2) was provided in NHANES and was calculated from weight and height measured as part of the physical examination component. We then defined obesity based on criteria from the CDC (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).42 As sexual minorities face significant barriers to healthcare access and utilization (such as stigma, negative healthcare experiences, lack of insurance coverage, etc.) compared to heterosexuals6,43 and there is evidence that they report low use of primary care services,44 we chose to examine hypertension, diabetes, and high total cholesterol using three different methods as follows: (1) current medication use, (2) self-reported medical history, and (3) biomarker data.6 Hypertension was established based on the 8th Joint National Committee guidelines (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg).45 Diagnosis of diabetes was based on a glycosylated hemoglobin ≥6.5%,46 and high total cholesterol was defined as ≥240 mg/dL.47

CVD diagnoses

Self-report of CVD conditions, including angina, coronary heart disease, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke, was used.48 Any participant who reported ever being diagnosed with at least one of these conditions was categorized as having CVD.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics

All statistical analyses were conducted in January 2017 using Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas). Sample weights for NHANES (2001–2012) were combined across data cycles before conducting analyses. Missing data patterns were also examined.

Multiple imputation

Multiple imputation with chained equations was conducted to impute missing values for demographic and clinical characteristics, mental distress, and health behaviors. There were no missing data for age, race/ethnicity, and family history of CVD. Missing data were highest for binge drinking (21.4%), physical activity (13.6%), and income (4.9%). There was less than 1% missing data for education, marital status, insurance, mental distress, current tobacco use, and fat intake. HIV status data were complete for 84.3% of participants, of whom 7.6% were HIV positive. Gay- (17.4%, P < 0.001) and bisexual-identified men (7.7%, P < 0.001) were more likely to be HIV positive compared to exclusively heterosexual men (0.3%). No heterosexual-identified MSM were HIV positive. As we decided not to impute missing values for biological measures a priori and the small number of HIV-positive participants (n = 51) produced unstable estimates in statistical analyses, HIV was excluded from further analyses. Furthermore, missing values did not differ significantly by sexual orientation. To reduce bias, the imputation model included all variables in the main model, including outcome variables.49 Structural variables (sampling weights, strata, and cluster) were included. A total of 20 imputations were performed, and imputation diagnostics were examined.

Statistical analyses

Sexual orientation differences for continuous and categorical variables were examined with the student t test and design-adjusted Rao-Scott chi-square test, respectively. The model presented in Figure 1 informed the regression analyses conducted. All multiple logistic regression models included demographic and clinical characteristics as covariates. In addition, models with health behaviors as outcomes were adjusted for mental distress, and models with biological risk factors and CVD diagnoses as outcomes were adjusted for mental distress and health behaviors. Models with hypertension, diabetes, and total cholesterol as outcomes also were adjusted for BMI and the model with CVD diagnoses as the outcome also was adjusted for BMI, hypertension, diabetes, and total cholesterol. Exclusively heterosexual men were the reference group for all analyses.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics are displayed in Table 1. NHANES (2001–2012) included a total sample of 30,558 men of whom 9077 had complete data for sexual identity. Figure 2 shows the process by which the final sample was obtained. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, the analytic sample consisted of 7731 men (7291 exclusively heterosexual, 147 gay-identified, 114 bisexual-identified, and 179 heterosexual-identified MSM) between the ages of 20 and 59. Gay- and bisexual-identified men were significantly more likely to report their marital status as single (p < 0.001) compared to exclusively heterosexual men. Gay-identified men had a higher family income to poverty ratio (p < 0.05), educational attainment (p < 0.001), and health insurance coverage (p < 0.001) relative to exclusively heterosexual men, whereas bisexual-identified men had a significantly lower family income to poverty ratio than exclusively heterosexual men (p < 0.05). Heterosexual-identified MSM were similar across demographic/clinical characteristics to exclusively heterosexual men, but were more likely to report a family history of CVD (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Total sample (n = 7731) | Exclusively heterosexual men (n = 7291) | Gay-identified men (n = 147) | Exclusively heterosexual vs. gay-identified men | Bisexual-identified men (n = 114) | Exclusively heterosexual vs. bisexual-identified men | Heterosexual-identified MSM (n = 179) | Exclusively heterosexual vs. heterosexual-identified MSM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or mean | % or mean | % or mean | p | % or mean | p | % or mean | p | |

| Age | 0.19 | 0.73 | 0.84 | |||||

| 20–29 | 24.8 | 25.1 | 15.3 | 28.8 | 20.7 | |||

| 30–39 | 24.9 | 24.7 | 33.0 | 28.0 | 26.4 | |||

| 40–49 | 26.3 | 26.4 | 24.9 | 20.9 | 28.1 | |||

| 50–59 | 23.9 | 23.8 | 26.8 | 22.3 | 24.8 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.84 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 70.4 | 70.3 | 73.9 | 70.7 | 71.1 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 10.2 | 10.3 | 6.5 | 11.7 | 9.4 | |||

| Hispanic | 14.1 | 14.1 | 11.6 | 15.4 | 15.5 | |||

| Other | 5.3 | 5.3 | 8.0 | 2.2 | 4.0 | |||

| Education | <0.001*** | 0.97 | 0.15 | |||||

| Less than high school | 14.9 | 15.3 | 3.2 | 15.9 | 9.6 | |||

| High school | 24.1 | 24.6 | 12.1 | 24.4 | 19.6 | |||

| Some college | 33.0 | 32.9 | 27.7 | 34.7 | 41.8 | |||

| College graduate or above | 28.0 | 27.2 | 57.0 | 24.9 | 29.0 | |||

| Marital status | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | 0.16 | |||||

| Married/partnered | 64.0 | 65.4 | 38.6 | 32.8 | 52.2 | |||

| Widowed | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.8 | |||

| Divorced | 8.4 | 8.4 | 2.0 | 13.8 | 13.5 | |||

| Separated | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 3.9 | 3.9 | |||

| Single | 24.6 | 23.3 | 58.1 | 49.3 | 29.6 | |||

| Family income–poverty ratio (mean) | 3.17 | 3.16 | 3.63 | 0.03* | 2.75 | 0.02* | 3.17 | 0.99 |

| CVD family history | 20.6 | 20.5 | 20.3 | 0.97 | 27.7 | 0.20 | 29.7 | 0.01* |

| Health insurance | 74.4 | 74.1 | 89.2 | <0.001*** | 67.7 | 0.23 | 75.1 | 0.90 |

Reference group = exclusively heterosexual men for all analyses.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

CVD, cardiovascular disease; MSM, men who have sex with men.

FIG. 2.

Flowchart of inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Findings for modifiable risk factors for CVD and CVD diagnoses are presented in Table 2. No differences between exclusively heterosexual and heterosexual-identified MSM were noted for any outcome. Although bisexual-identified men were significantly more likely to experience frequent mental distress in the past 30 days (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.39, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.46–3.90), they reported no difference in health behaviors compared to exclusively heterosexual men. With the exception of significantly lower report of binge drinking (AOR 0.58, 95% CI = 0.37–0.85), gay-identified men had similar health behaviors to exclusively heterosexual men. Bisexual-identified men had significantly higher odds of obesity compared to exclusively heterosexual men (AOR 1.69, 95% CI = 1.02–2.72) and were more likely to have been told that they had diabetes by a healthcare professional (AOR 3.53, 95% CI = 1.74–7.14). Gay-identified men and heterosexual-identified MSM had similar rates of antidiabetic medication use as exclusively heterosexual men, whereas bisexual-identified men had higher use of this class of medications (AOR 2.83, 95% CI = 1.20–6.68). Bisexual-identified men also had significantly higher rates of elevated blood pressure (AOR 2.30, 95% CI = 1.43–3.70) and glycosylated hemoglobin (AOR 3.01, 95% CI = 1.38–6.59). In addition, no sexual orientation differences in total cholesterol or self-report of CVD were detected.

Table 2.

Sexual Orientation Differences in Modifiable Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiovascular Disease Diagnoses (n = 7731)

| % | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental distress | |||

| Frequent mental distress | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 10.1 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 13.0 | 1.33 (0.77–2.31) | 1.56 (0.86–2.81)a |

| Bisexual identified | 22.6* | 2.61 (1.60–4.24)* | 2.39 (1.46–3.90)a* |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 9.9 | 0.98 (0.57–1.66) | 1.01 (0.60–1.70)a |

| Health behaviors | |||

| Current tobacco use | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 28.7 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 35.0 | 1.34 (0.78–2.29) | 1.46 (0.85–2.48)b |

| Bisexual identified | 38.4 | 1.56 (0.94–2.60) | 1.22 (0.72–2.07)b |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 24.3 | 0.80 (0.49–1.32) | 0.82 (0.49–1.37)b |

| Binge drinking | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 54.5 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 48.3 | 0.74 (0.50–1.10) | 0.58 (0.37–0.85)b* |

| Bisexual identified | 47.8 | 0.87 (0.46–1.62) | 0.74 (0.35–1.55)b |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 45.9 | 0.79 (0.51–1.22) | 0.76 (0.48–1.18)b |

| Meets physical activity recommendations | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 51.4 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 45.1 | 0.83 (0.52–1.31) | 0.78 (0.49–1.25)b |

| Bisexual identified | 44.1 | 0.71 (0.39–1.32) | 0.69 (0.37–1.27)b |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 41.0 | 0.68 (0.41–1.12) | 0.70 (0.40–1.11)b |

| Adequate fat intake | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 17.5 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 21.7 | 1.30 (0.81–2.09) | 0.98 (0.59–1.63)b |

| Bisexual identified | 18.0 | 1.03 (0.56–1.91) | 0.98 (0.52–1.83)b |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 16.4 | 0.92 (0.56–1.52) | 0.87 (0.53–1.45)b |

| BMI | |||

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 33.1 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 22.7* | 0.59 (0.38–0.93)* | 0.81 (0.52–1.29)c |

| Bisexual identified | 42.0 | 1.46 (0.91–2.34) | 1.69 (1.02–2.72)c* |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 30.4 | 0.88 (0.54–1.43) | 0.91 (0.57–1.46)c |

| Hypertension | |||

| Antihypertensive medication | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 13.4 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 7.8 | 0.54 (0.25–1.18) | 0.58 (0.23–1.44)d |

| Bisexual identified | 20.4 | 1.66 (0.87–3.15) | 1.87 (0.97–3.63)d |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 12.8 | 0.95 (0.54–1.66) | 0.89 (0.45–1.75)d |

| Told had hypertension | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 24.2 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 17.3 | 0.66 (0.39–1.11) | 0.64 (0.34–1.16)d |

| Bisexual identified | 31.4 | 1.43 (0.79–2.61) | 1.35 (0.73–2.47)d |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 26.8 | 1.14 (0.70–1.88) | 1.12 (0.63–1.99)d |

| Hypertension (SBP ≥140 and/or DBP ≥90) | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 11.7 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 5.0* | 0.40 (0.16–0.98)* | 0.43 (0.17–1.14)d |

| Bisexual identified | 23.7* | 2.33 (1.49–3.64)* | 2.30 (1.43–3.70)d* |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 12.5 | 1.07 (0.51–2.27) | 1.06 (0.53–2.11)d |

| Diabetes | |||

| Antidiabetic medication | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 3.9 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 0.6* | 0.15 (0.02–1.15) | 0.18 (0.02–1.48)d |

| Bisexual identified | 9.7* | 2.63 (1.19–5.85)* | 2.83 (1.20–6.68)d* |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 2.3 | 0.57 (0.23–1.42) | 0.47 (0.19–1.17)d |

| Told had diabetes | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 4.9 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 1.3* | 0.25 (0.06–1.02) | 0.29 (0.06–1.35)d |

| Bisexual identified | 14.5* | 3.30 (1.69–6.44)* | 3.53 (1.74–7.14)d* |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 3.0 | 0.61 (0.27–1.38) | 0.53 (0.23–1.18)d |

| Diabetes (HbA1c ≥6.5%) | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 4.9 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 0.7* | 0.13 (0.02–0.85)* | 0.19 (0.03–1.36)d |

| Bisexual identified | 12.4* | 2.76 (1.41–5.40)* | 3.01 (1.38–6.59)d* |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 3.8 | 0.76 (0.36–1.62) | 0.70 (0.34–1.47)d |

| Cholesterol | |||

| Cholesterol-lowering medication | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 8.8 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 6.7 | 0.75 (0.27–2.07) | 0.95 (0.27–3.35)d |

| Bisexual identified | 11.8 | 1.38 (0.45–4.28) | 1.90 (0.48–7.45)d |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 14.3 | 1.73 (0.86–3.46) | 1.88 (0.88–4.02)d |

| Told had high cholesterol | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 26.6 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 25.1 | 0.92 (0.55–1.56) | 0.87 (0.44–1.75)d |

| Bisexual identified | 23.9 | 0.86 (0.44–1.71) | 0.97 (0.50–1.90)d |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 35.3 | 1.50 (0.91–2.46) | 1.57 (0.99–2.50)d |

| High total cholesterol (≥240 mg/dL) | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 15.6 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 13.1 | 0.82 (0.46–1.47) | 0.93 (0.48–1.78)d |

| Bisexual identified | 12.7 | 0.79 (0.38–1.63) | 0.81 (0.36–1.84)d |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 16.6 | 1.08 (0.62–1.85) | 1.10 (0.65–1.86)d |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

| CVD | |||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 3.7 | Ref | Ref |

| Gay identified | 2.1 | 0.57 (0.17–1.89) | 0.68 (0.18–2.60)e |

| Bisexual identified | 4.8 | 1.33 (0.53–3.37) | 1.05 (0.37–2.98)e |

| Heterosexual-identified MSM | 4.0 | 1.10 (0.41–2.94) | 0.94 (0.33–2.64)e |

P < 0.05.

Adjusted for age, race, education, marital status, and income.

Adjusted for age, race, education, marital status, income, and frequent mental distress. cAdjusted for age, race, education, marital status, income, insurance, CVD family history, frequent mental distress, tobacco use, binge drinking, physical activity, and fat intake.

Adjusted for age, race, education, marital status, income, insurance, CVD family history, frequent mental distress, BMI, tobacco use, binge drinking, physical activity, and fat intake.

Adjusted for age, race, education, marital status, income, insurance, CVD family history, frequent mental distress, BMI, tobacco use, binge drinking, physical activity, fat intake, hypertension, diabetes, and high total cholesterol.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; OR, odds ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Discussion

Given previous evidence,9 we hypothesized that gay- and bisexual-identified men would have higher modifiable risk factors for CVD and CVD diagnoses compared to exclusively heterosexual men. Although this was supported for bisexual-identified men across several CVD risk factors, gay- and heterosexual-identified MSM demonstrated similar CVD risk to their exclusively heterosexual peers. Gay-identified men in the present study reported lower rates of binge drinking than exclusively heterosexual men, which corroborates the findings of previous studies.10,14,16

Our findings suggest that bisexual-identified men, in particular, have higher CVD risk compared to exclusively heterosexual men across several modifiable risk factors. A recent study conducted by Dyar et al. found that bisexual-identified men had higher rates of self-reported obesity, high total cholesterol, and hypertension than heterosexual men.50 We did not identify significant differences for high total cholesterol. However, our findings were consistent for obesity and hypertension. Few studies have found higher objectively measured BMI levels in bisexual-identified men. An analysis of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health revealed that gay-identified men displayed lower objectively measured BMI than heterosexual men, and no significant difference in BMI levels was observed between bisexual-identified and heterosexual men.51

Furthermore, in addition to higher rates of mental distress and obesity, bisexual-identified men demonstrated increased prevalence for one of three measures of hypertension (blood pressure, but not medication use or medical history) and all three measures of diabetes (medication use, medical history, and glycosylated hemoglobin) that were examined. These findings suggest a lack of awareness and treatment of hypertension among bisexual-identified men. Our findings contradict those of a previous analysis of the California Health Interview Survey that revealed bisexual-identified men 60 years and older were significantly more likely to report antihypertensive medication use.52 The present study was limited to participants between the ages of 18 and 59. Therefore, medication use in individuals over the age of 59 was not assessed. Diabetes is an established risk factor for CVD.53 To our knowledge, the higher prevalence of elevated glycosylated hemoglobin in bisexual-identified men we observed in the present study has not been described previously in the literature. One explanation for heightened health disparities among bisexual-identified individuals (termed the double closet phenomenon) posits that they experience higher levels of stress from having to hide different aspects of their lives from heterosexual and sexual minority peers.54 The higher CVD risk that we observed in bisexual-identified men appears to support the “double closet phenomenon”; however, additional research is needed to assess differences between gay- and bisexual-identified men and examine potential contributors to CVD disparities in bisexual men.

We did not identify any differences in CVD risk between heterosexual-identified MSM and exclusively heterosexual men. Our ability to compare our results to previous studies is limited as few studies have examined CVD risk in heterosexual-identified MSM. An analysis of data from the California Quality of Life Survey revealed that heterosexual-identified MSM reported higher rates of CVD diagnosis than exclusively heterosexual men.55 However, the small number of heterosexual-identified MSM examined (n = 23) in that study limits confidence in the findings. A more recent study found that heterosexual-identified MSM may have a lower 10-year risk of experiencing a CVD event compared to exclusively heterosexual men.56 As existing evidence is conflicting, there is a need to investigate CVD risk in heterosexual-identified MSM. In addition, several studies indicate that concealment of sexual orientation is associated with poor mental and physical well-being in gay and bisexual men.57,58 For heterosexual-identified MSM, in particular, concealment of same-sex sexual behavior is associated with higher rates of poor mental health.59 The potential association between concealment of sexual orientation and CVD risk remains an unexplored area of research.

Limitations

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey. Therefore, causality cannot be inferred from these data. The measure of psychological stress used in NHANES is a measure of acute stress in the past 30 days. Measures of chronic stress and minority stress (including experiences with marginalization, internalized stigma, expectations of rejection, etc.) were not available in NHANES. The dietary measure used in this study was based on a single item with potential for recall bias. Although it is recognized that CVD increases with age, CVD risk in individuals over the age of 59 was not assessed. Another limitation of this study is that HIV was excluded from analyses due to the low number of participants who were HIV positive. Future work should examine the unique contribution of HIV to CVD risk in sexual minority men.

Implications for research, policy, and practice

Future studies should examine sexual orientation differences in CVD risk to determine whether the observed differences in bisexual-identified men are documented in other samples. We also identified a need for further study of CVD risk in heterosexual-identified MSM. Researchers in Canada recently found that 30% of gay- and bisexual-identified men were unwilling to disclose their sexual orientation in national population-based surveys.60 This can lead to misclassification of sexual orientation and obscure differences between sexual minority and heterosexual participants. It is possible that sexual minority men who agree to participate in population-based surveys may be different from those who do not. More research on the extent of sexual orientation misclassification in the United States and methods for recruiting sexual minority men for population-based surveys is needed.

Despite concerns about the representativeness of sexual minority participants in population-based surveys, there is a need for continued inclusion and refinement of sexual orientation items. Recently, the U.S. Government enacted steps to remove sexual orientation measures from several national surveys.61 Collecting sexual orientation data that address its multiple dimensions is critical to understanding the health of sexual minority men. Therefore, there is a need to advocate for continued inclusion of sexual orientation items in national, state, and local health surveys.

Our findings can inform practice for clinicians and public health practitioners. Although no difference in health behaviors was observed between bisexual-identified and exclusively heterosexual men, bisexual-identified men demonstrated excess CVD risk, including frequent mental distress, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. Poor mental health is a recognized risk factor for the development of CVD.33,62–64 Thus, these findings support that clinicians should routinely screen bisexual-identified men for poor mental health as a CVD risk factor. Data suggest that clinicians should receive education about sexual minority health.65,66 Clinicians should be informed about how sexual minority identity may impact prevalence of modifiable risk factors for CVD and other health conditions in this population. This is particularly important as healthcare organizations increasingly include sexual orientation as part of demographic questionnaires in electronic health records.67 Clinicians and public health practitioners should develop CVD prevention strategies that address the unique needs of bisexual-identified men.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on sexual orientation differences in CVD risk among men. Gay-identified and heterosexual-identified MSM demonstrated a similar CVD risk profile to exclusively heterosexual men. On the contrary, bisexual-identified men had increased CVD risk, including frequent mental distress, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. This study underscores the importance of disaggregating analyses for gay- and bisexual-identified participants to ascertain differences in health outcomes between subgroups. These findings can inform future research in the area of sexual minority health. In particular, the need to perform mental health and CVD risk screenings and develop CVD risk prevention for bisexual-identified men is underscored.

Acknowledgments

BAC was supported by a predoctoral institutional training grant (TL1TR001147) from New York University-H+H Clinical and Translational Science Institute and a postdoctoral T32 fellowship (T32NR014205) in Comparative and Cost-Effectiveness Research Training for Nurse Scientists. The sponsor had no role in the study design, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing the article, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. NCD mortality and morbidity. 2017. Available at www.who.int/gho/ncd/mortality_morbidity/en Accessed July2, 2017

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. : Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135:e146–e603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Heart Association: Cardiovascular Disease: A Costly Burden for America—Projections through 2035. Washington DC: American Heart Association, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. : Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004;364:937–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. : Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;132:873–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities: The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frost DM, Lehavot K, Meyer IH: Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. J Behav Med 2015;38:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer IH: Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caceres BA, Brody A, Luscombe RE, et al. : A systematic review of cardiovascular disease in sexual minorities. Am J Public Health 2017;107:e13–e21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garland-Forshee RY, Fiala SC, Ngo DL, Moseley K: Sexual orientation and sex differences in adult chronic conditions, health risk factors, and protective health practices, Oregon, 2005–2008. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:E136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dilley JA, Simmons KW, Boysun MJ, et al. : Demonstrating the importance and feasibility of including sexual orientation in public health surveys: Health disparities in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health 2010;100:460–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthews DD, Lee JG: A profile of North Carolina lesbian, gay, and bisexual health disparities, 2011. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e98–e105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minnis AM, Catellier D, Kent C, et al. : Differences in chronic disease behavioral indicators by sexual orientation and sex. J Public Health Manag Pract 2016;22 Suppl 1:S25–S32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, et al. : Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. Am J Public Health 2013;103:1802–1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N: Sexual orientation disparities in cardiovascular biomarkers among young adults. Am J Prev Med 2013;44:612–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everett B, Mollborn S: Differences in hypertension by sexual orientation among U.S. young adults. J Community Health 2013;38:588–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrick SSC, Duncan LR: A systematic scoping review of engagement in physical activity among LGBTQ+ adults. J Phys Act Health 2018;15:226–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatzenbuehler ML, Slopen N, McLaughlin KA: Stressful life events, sexual orientation, and cardiometabolic risk among young adults in the United States. Health Psychol 2014;33:1185–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bavinger C, Bendavid E, Niehaus K, et al. : Risk of cardiovascular disease from antiretroviral therapy for HIV: A systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e59551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiage JN, Heimburger DC, Nyirenda CK, et al. : Cardiometabolic risk factors among HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy. Lipids Health Dis 2013;12:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DAD Study Group, Friis-Møller N, Reiss P, et al. : Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1723–1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kariuki W, Manuel JI, Kariuki N, et al. : HIV and smoking: Associated risks and prevention strategies. HIV/AIDS (Auckl) 2015;8:17–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nahvi S, Cooperman NA: Review: The need for smoking cessation among HIV-positive smokers. AIDS Educ Prev 2009;21 (3 Suppl):14–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freiberg MS, McGinnis KA, Kraemer K, et al. : The association between alcohol consumption and prevalent cardiovascular diseases among HIV infected and HIV-uninfected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;53:247–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein JH, Currier JS, Hsue PY: Arterial disease in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: What has imaging taught us? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:515–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duprez DA, Neuhaus J, Kuller LH, et al. : Inflammation, coagulation and cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected individuals. PLoS One 2012;7:e44454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS: Basic statistics. 2017. Available at www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html Accessed January10, 2018

- 28.Caceres BA, Brody A, Chyun D: Recommendations for cardiovascular disease research with lesbian, gay and bisexual adults. J Clin Nurs 2016;25:3728–3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL: Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspect Psychol Sci 2013;8:521–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Psychological Association: Stress and Health Disparities. Contexts, Mechanisms, and Interventions among Racial/ethnic Minority and Low Socioeconomic Status Populations. 2017. Available at www.apa.org/pi/health-disparities/resources/stress-report.aspx Accessed January3, 2018

- 31.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE: Psychological stress and disease. JAMA 2007;298:1685–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McEwen BS, Stellar E: Stress and the individual: Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:2093–2101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue YT, Tan QW, Li P, et al. : Investigating the role of acute mental stress on endothelial dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Cardiol 2015;104:310–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang DH, Rice M, Park NJ, et al. : Stress and inflammation: A biobehavioral approach for nursing research. West J Nurs Res 2010;32:730–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson CL, Dohrmann SM, Burt VL, Mohadjer LK: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Sample design, 2011–2014. Vital Health Stat 2014;2:1–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson CL, Paulose-Ram R, Ogden CL, et al. : National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Analytic Guidelines, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat 2013;2:1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sell RL: Defining and measuring sexual orientation: A review. Arch Sex Behav 1997;26:643–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health-related quality of life: Frequently asked questions. 2016. Available at www.cdc.gov/hrqol/faqs.htm#3 Accessed July7, 2017

- 39.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: NIAAA Council Approves Definition of Binge Drinking. NIAAA Newsletter. 2004. Available at http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/winter2004/Newsletter_Number3.pdf Accessed October14, 2017

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How much physical activity do adults need? 2015. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adults/index.htm Accessed July25, 2017

- 41.Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, et al. : Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:569–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining adult overweight and obesity. 2016. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html Accessed December28, 2017

- 43.Kates J, Ranji U, Beamesderfer A, et al. : Health and Access to Care and Coverage for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Individuals in the U.S. 2017. Available at http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Health-and-Access-to-Care-and-Coverage-for-LGBT-Individuals-in-the-US Accessed February26, 2018

- 44.Qureshi RI, Zha P, Kim S, et al. : Health care needs and care utilization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations in New Jersey. J Homosex 2018;65:167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. : 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014;311:507–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care 2017;40 (Suppl 1):s4–s128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. How is high blood cholesterol diagnosed? 2016. Available at https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/hbc/diagnosis Accessed September14, 2017

- 48.World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). 2017. Available at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en Accessed January18, 2018

- 49.Johnson DR, Young R: Toward best practices in analyzing datasets with missing data: Comparisons and recommendations. J Marriage Fam 2011;73:926–945 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dyar C, Taggart TC, Rodriguez-Seijas C, et al. : Physical health disparities across dimensions of sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and sex: Evidence for increased risk among bisexual adults. Arch Sex Behav 2018. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1007/s10508-018-1169-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clark CJ, Borowsky IW, Salisbury J, et al. : Disparities in long-term cardiovascular disease risk by sexual identity: The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Prev Med 2015;76:26–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boehmer U, Miao X, Linkletter C, Clark MA: Health conditions in younger, middle, and older ages: Are there differences by sexual orientation? LGBT Health 2014;1:168–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fox CS: Cardiovascular disease risk factors, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the Framingham Heart Study. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2010;20:90–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zinik G: Identity conflict or adaptive flexibility? Bisexuality reconsidered. J Homosex 1985;11:7–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cochran SD, Mays VM: Physical health complaints among lesbians, gay men, and bisexual and homosexually experienced heterosexual individuals: Results from the California Quality of Life Survey. Am J Public Health 2007;97:2048–2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Farmer GW, Bucholz KK, Flick LH, et al. : CVD risk among men participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2001 to 2010: Differences by sexual minority status. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:772–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morandini JS, Blaszczynski A, Ross MW, et al. : Essentialist beliefs, sexual identity uncertainty, internalized homonegativity and psychological wellbeing in gay men. J Couns Psychol 2015;62:413–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quinn DM, Weisz BM, Lawner EK: Impact of active concealment of stigmatized identities on physical and psychological quality of life. Soc Sci Med 2017;192:14–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schrimshaw EW, Siegel K, Downing MJ, Parsons JT: Disclosure and concealment of sexual orientation and the mental health of non-gay-identified, behaviorally bisexual men. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81:141–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferlatte O, Hottes TS, Trussler T, Marchand R: Disclosure of sexual orientation by gay and bisexual men in government-administered probability surveys. LGBT Health 2017;4:68–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cahill SR, Makadon HJ: If they don't count us, we don't count: Trump administration rolls back sexual orientation and gender identity data collection. LGBT Health 2017;4:171–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jood K, Redfors P, Rosengren A, et al. : Self-perceived psychological stress and ischemic stroke: A case-control study. BMC Med 2009;7:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. : Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11 119 cases and 13 648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004;364:953–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pikhart H, Pikhartova J: The relationship between psychosocial risk factors and health outcomes of chronic diseases. A review of the evidence for cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2015. Available at www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/273737/OMS-EURO-HEN-PsychologicalFactorsReport-A5-20150320-v5-FINAL.pdf?ua=1 Accessed February1, 2017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carabez R, Pellegrini M, Mankovitz A, et al. : “Never in all my years…”: Nurses' education about LGBT health. J Prof Nurs 2015;31:323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. : Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender—related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA 2011;306:971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cahill S, Makadon H: Sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in clinical settings and in electronic health records: A key to ending LGBT health disparities. LGBT Health 2014;1:34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]