Abstract

Background/Aims

Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) is a prevalent functional bowel disorder. Abdominal pain, discomfort and altered intestinal habits are the salient features of IBS-D. Low grade inflammation and altered neurotransmitters are the 2 recently identified factors contributing to the pathogenesis of IBS-D, but their role and interactions has not been elucidated in detail. Here we investigate the potential role of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in regulating gut inflammation during IBS-D.

Methods

Blood samples and colonic mucosal biopsies from clinically diagnosed IBS-D patients and controls were collected. Levels of GABA were measured in serum samples through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Expression of GABAergic system and proinflammatory cytokines were analyzed in biopsy samples by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Effect of GABA and its antagonist on the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated HT-29 cells was examined through RT-PCR.

Results

ELISA data revealed diminished level of GABA in IBS-D patients as compared to controls. RT-PCR analysis showed altered GABAergic signal system in IBS-D patients as compared to controls. GABA reduced the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in LPS stimulated HT-29 cells, whereas bicuculline methiodide (GABA antagonist) upregulated the expression of same cytokines in LPS stimulated HT-29 cells.

Conclusions

Our sets of data indicate that diminished level of GABA and altered GABAergic signal system contributes to pathogenesis of IBS-D by regulating inflammatory processes. These results provide novel evidence for anti-inflammatory role of GABA in IBS-D patients by altering the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Keywords: Cytokines, Gamma-aminobutyric acid, Inflammation, Irritable bowel syndrome, Lipopolysaccharides

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder. Abdominal pain or discomfort with altered stool frequency and consistency are the main characteristic features of IBS. The pathophysiology of IBS is still ill-defined but it is considered to be multifactorial in nature.1 On the basis of bowel habits, it is classified into 3 types: diarrhea predominant (IBS-D), constipation predominant (IBS-C), and alternating between the 2 states or mixed (IBS-M).2

Though IBS-M is the most prevalent form of IBS in India it is difficult to diagnose patients of IBS-M because patients switch to different subtypes with time, depending on their predominant symptoms. IBS-D is on the second number in terms of prevalence in India.3 Previous reports suggest that a low-grade mucosal inflammation is a contributory factor in the IBS-D pathogenesis.4 Even immune cell infiltration and their activation in the colon mucosa of IBS patients have been proposed. Immune cell infiltration includes T cells and mast cells whereas immune cell activation includes release of cytokines, histamine, proteases etc.5 Brint et al,6 showed differential expression of toll-like receptors (TLRs) in IBS patients suggesting potential involvement of an innate immune response in this complex disorder.

Recent evidences suggest alteration in release of neurotransmitters attributed to the occurrence of IBS-D.7 Various neurotransmitters like serotonin or substance P are known to play a role in pathophysiology of IBS-D.8,9 Jembrek et al10 reported the expression of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors in the gastrointestinal system and described the role of GABA in diverse gastrointestinal functions specifically stress related disorders. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter of CNS, however it regulates various processes in peripheral organs including inflammation in the colon.11 Inside the colon, epithelial cells are endowed with a functional GABAergic signal system.12 The GABAergic signal system involves glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) which synthesizes GABA, GABA-transaminase (GABA-T) that catabolise GABA, GABA-receptor (GABA-R), and GABA transporter (GAT). GAD exists as 2 isoforms GAD1 and GAD2. GABA-R is of 2 types: GABA-A receptor (GABA-AR) and GABA-B receptor (GABA-BR). GABA-AR is a pentameric chloride channel containing 19 different subunits (α1-6, β1-3, γ1-3, δ, ɛ, π, θ, and ρ1-3).13 Out of 19 subunits, the π subunit is the only subunit expressed in peripheral organs.12 GABA-BR is a heterodimer composed of 2 subunits, GABA-B1R, and GABA-B2R.14 GAT is a GABA transporter involved in reup-take of GABA from the extracellular space into the cytosol.15 Out of 4 subtypes of GAT, GAT-2 is the only known transporter expressed in peripheral organs.16 GABA and the components of GABAergic signal system are found to be altered in various diseases including cancer.17 GABA is also reported to downregulate p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activity and p38 MAPK is known to upregulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines.18–20 Therefore, GABA can inhibit the production of proinflammatory cytokines by downregulating p38 MAPK. Here we hypothesized that alteration in various components of GABAergic signal system may be one of the contributing factors in the pathogenesis of IBS-D.

The purpose of this study was to find the expression of GABA and GABAergic signal system in IBS-D patients, and also to elucidate the potential role of GABA in regulation of inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

Blood and colonic mucosal biopsy specimens were collected from IBS-D patients and controls. Adult IBS-D patients were diagnosed on the basis of the Rome III criteria.21 Controls included adult cases of suspected haemorrhoidal bleeding, being taken up for sigmoidoscopy, with no intestinal or other inflammatory disease. We obtained biopsy samples from the descending colon during sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. Patients were excluded if they were IBS-C or IBS-M; pregnant; known human immunodeficiency virus, Hepatitis B virus infection, symptoms or signs suggestive of these infections or not willing to participate in the study.

Demographic features of study participants and sample details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Features of Study Subjects

| Type of specimen | IBS-D | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Blood | Biopsy | Blood | Biopsy | |

| No. | 30 | 23 | 29 | 25 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 35.00 ± 10.12 | 33.13 ± 6.52 | 34.34 ± 9.55 | 34.04 ± 9.83 |

| Sex (M/F) | 23/7 | 17/6 | 25/4 | 22/3 |

IBS-D, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome; M, male; F, female.

The patients were recruited by the Department of Gastroenterology of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, India. Ethical approval for this study was obtained by the ethical committee of AIIMS (Ref No. IESC/T-174/2014) and the institutional ethics review board, JNU (Ref No. 2014/student/61). Written informed consent was taken from all the participants included in this study.

Serum Isolation for Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

Serum separator tubes were used for blood samples collection and serum isolation was done by centrifuging them at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant (serum) was immediately stored at −80°C till further processing. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to determine the levels of GABA and GAD in serumfollowing the manufacturer’s protocol (Krishgen Biosystems, Mumbai, India).

Cell Culture

To carry out in vitro studies, the HT-29 Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line was obtained from National Center for Cell Science (Pune, India). Cells were routinely maintained in a Dulbeco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium with high glucose (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 5% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum and 5% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermofisher Scientific). Cells were kept at 37°C in a humidified (5% CO2, 95% air) incubator under standard conditions. Cell culture media was changed 2–3 times a week and cells were subcultured at 90% confluency.

Reagents used were GABA, lipopolysaccharides from Escherichia coli O111:B4 and GABA-A receptor antagonist: 1(S), 9(R)-(−)-bicuculline methiodide. All were purchased from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Protocol to Study Lipopolysaccharide-induced Inflammation

HT-29 cells were inoculated in 12-well tissue culture plates and incubated in DMEM media at 37°C. At 90% confluency of cells, treatments were given in 6 sets. Concentration and duration of each treatment was decided on the basis of previous studies.22,23 The protocol used included 6 sets of treatments. The first set contained HT-29 cells without any treatment. Second set included HT-29 cells treated with 1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharides (LPS) for 4 hours. Third set consisted of HT-29 cells treated with 100 μM GABA for 2 hours. Fourth set contained HT-29 cells treated with 100 μM GABA for 2 hours followed by 4 hours stimulation with 1 μg/mL LPS. Fifth set included HT-29 cell treated with 100 μM bicuculline methiodide (BMI) for 2 hours. Sixth set contained HT-29 cells treated with 100 μM BMI for 2 hours followed by 4 hours stimulation with 1 μg/mL LPS. After giving treatments, cells were harvested from all the sets and the total RNA was isolated. Each set was taken in triplicate.

RNA Isolation and Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

Colon biopsy samples were collected in RNA later solution. Total RNA was extracted from colon biopsy samples and harvested cells by using RNA isolation kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed by a random hexamer primer (Fermentas, St. Leon Rot, Germany). Sequence of primers used in real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are given in Table 2. Real-time PCR was performed using the ABI PRISM 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Parameters for real-time were—initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 minutes followed by denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 1 minute and continued for 40 cycles. Twenty microliter reaction containing 7 μL MQ water, 10 μL SYBER Green universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 1 μL of each forward and reverse primer (4 picomole/μL), and 1 μL cDNA was prepared. Relative quantification of cDNA was done using the ΔΔCT method following normalization with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).24

Table 2.

Primer Sequences Used for Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

| Genes | Sequence (5’–3’) | Amplicon |

|---|---|---|

| GAD2 | FP: CGAGTCCCTGGAGCAGATCCTGGTT RP: GTCAGCCATTCTCCAGCTAGGCCAATAATA |

132 bp |

| GABA-T | FP: GACGGAAGTCCCAGGGCC RP: GGAGCCACCGAGAGCAA |

315 bp |

| π subunit of GABA-AR | FP: ACGTCGAGGTCGGCAGAA RP: CCCGCCTCGTGGAGTTC |

275 bp |

| B1 subunit of GABA-BR | FP:CAGATAAATGGATTGGAGGGT RP:GAGAACTGAGACGGAGATAAAGAG |

101 bp |

| B2 subunit of GABA-BR | FP:GAGTCCACGCCATCTTCAAAAAT RP:TCAGGATACACAGGTCGATCAGC |

108 bp |

| GAT-2 | FP: CCCCAGGTGTGGATGGATGC RP: TGCTCCTGAGACATGAAGCCCA |

203 bp |

| IL-1β | FP: CTCTCTCACCTCTCCTACTCAC RP: ACACTGCTACTTCTTGCCCC |

188 bp |

| IL-6 | FP: GTAGCCGCCCCACACAGA RP: CATGTCTCCTTTCTCAGGGCTG |

101 bp |

| TNF-α | FP: CCCCAGGGACCTCTCTCTAA RP: TGAGGTACAGGCCCTCTGAT |

212 bp |

| IL-8 | FP: ACTGAGAGTGATTGAGAGTGGAC RP: AACCCTCTGCACCCAGTTTTC |

112 bp |

| GAPDH | FP: GCTCCTCCTGTTCGACAGTCA RP: GCAACAATATCCACTTTACCAG |

180 bp |

GAD2, glutamic acid decarboxylase 2; GABA-T, γ-aminobutyric acid transaminase; GABA-AR, GABA-A receptor; GABA-BR, GABA-B receptor; GAT-2, GABA transporter subtype 2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; FP, forward primer; RP, reverse primer.

Statistical Methods

ELISA data was analyzed by Curve Expert 1.4 software. The relative expression (fold change) was calculated using the equation 2−ΔΔCT where ΔΔCT = ΔCT target gene − ΔCT GAPDH. Statistical analysis was done using unpaired, two way Student’s t test. All sets of data are represented as mean ± SEM. A probability level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Estimation of γ-Aminobutyric Acid and GABAergic Signal System

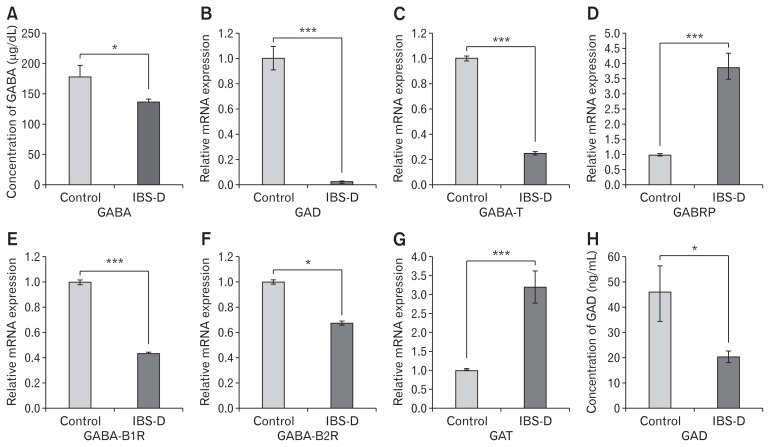

Levels of GABA were decreased significantly in the serum of IBS-D as compared to controls (Fig. 1A). Relative mRNA expression of GAD2 and GABA-T was significantly reduced in IBS-D patients as compared to controls (Fig. 1B and 1C). GABA receptors are of 2 types A and B. π subunit of GABA-A receptor (GA-BRP) is the only subunit expressed in peripheral organs. Hence we specifically looked at the expression of GABRP. A significant increase in expression of GABRP was observed in patients suffering from IBS-D as compared to controls (Fig. 1D). GABA-B receptors consist of 2 subunits B1 and B2. Expression of both subunits was significantly reduced in IBS-D as compared to controls (Fig. 1E and 1F). Expression of GAT was significantly increased in IBS-D patients as compared to controls (Fig. 1G)

Figure 1.

Quantification of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in serum and analysis of expression of GABAergic signal system in colon biopsy samples of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) patients and controls. (A) Concentration of GABA in human serum samples measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), control (n = 28) and IBS-D (n = 25). Relative mRNA expression of (B) glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). (C) GABA-transaminase (GABA-T). (D) π subunit of GABA-A receptor (GABRP). (E) B1 subunit of GABA-B receptor (GABA-B1R). (F) B2 subunit of GABA-B receptor (GABA-B2R). (G). GABA-transporter (GAT) in control (n = 20–25) and IBS-D (n = 20–23) determined through reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. (H). Concentration of GAD in serum samples measured by ELISA, (n = 20–25). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were examined with Student’s paired t tests. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 was considered to be significant.

Since GAD is principal enzyme involved in GABA production, we also looked at the expression of GAD at the protein level. Concentrations of GAD was significantly low in the serum of patients as compared to controls (Fig. 1H).

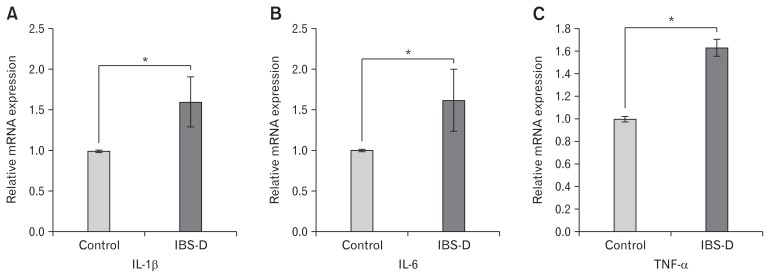

Relative Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines

Relative mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) was examined in the colonic mucosal biopsy of IBS-D patients and controls. Expression of all the proinflammatory cytokines were significantly upregulated in disease conditions as compared to controls (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Analysis of expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the colon biopsy samples of controls (n = 22–27) and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D; n = 20–23) through reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Relative mRNA expression of (A) IL-1β, (B) IL-6, and (C) TNF-α. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were examined with Student’s paired t tests. *P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

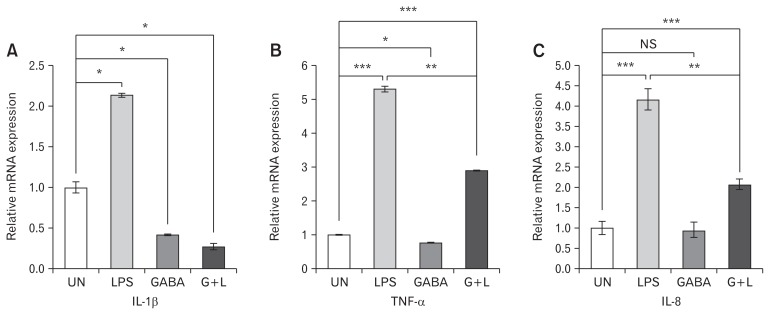

Anti-Inflammatory Role of γ-Aminobutyric Acid

In vitro studies were carried out to show the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-8). The expression of the above cytokines was significantly upregulated after stimulation of HT-29 cells with LPS. However, when LPS stimulated HT-29 cells were pre-treated with GABA, they exhibited decreased expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-8 as compared to only LPS stimulated HT-29 cells (Fig. 3A–C) respectively.

Figure 3.

Effect of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) on mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines in HT-29 cells. Treatment was given in 4 groups. (1) Untreated (UN), (2) lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 μg/mL) stimulated for 4 hours, (3) GABA (100 μM) induced for 2 hours, and (4) GABA (100 μM) induced for 2 hours followed by 4 hours of LPS (1 μg/mL) treatment (G + L). Relative mRNA expression of (A) IL-1β, (B) TNF-α, and (C) IL-8 was analyzed in all the 4 groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were examined with Student’s paired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 was considered to be significant. UN, untreated; LPS, LPS (1 μg/mL) stimulated for 4 hours; GABA, GABA (100 μM) induced for 2 hours; G + L, GABA (100 μM) induced for 2 hours followed by 4 hours of LPS (1 μg/mL) treatment; NS, not significant.

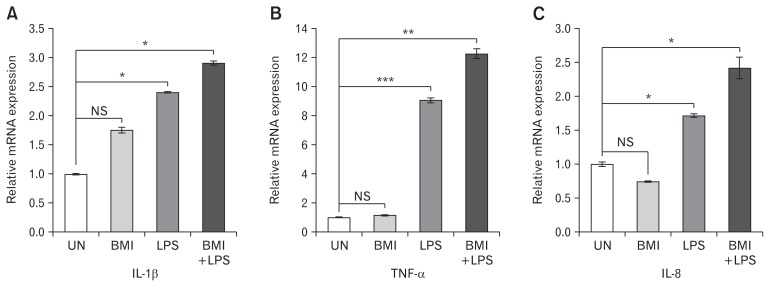

Effect of Bicuculline Methiodide (γ-Aminobutyric Acid-A Receptor Antagonist) on Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines

Prior treatment with the antagonist BMI was given to LPS stimulated HT-29 cells and the relative mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines was evaluated. Prior treatment with BMI to LPS stimulated HT-29 cells showed further upregulation in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines compared to only LPS stimulated cells. Significant increase in the expression of the cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-8 was observed (Fig. 4A–C) respectively.

Figure 4.

Effect of bicuculline methiodide (BMI) on mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines in HT-29 cells. Treatment was given in 4 groups. (1) Untreated (UN), (2) BMI (100 μM) induced for 2 hours, (3) lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 μg/mL) stimulated for 4 hours, (4) BMI (100 μM) induced for 2 hours followed by 4 hours of LPS (1 μg/mL) treatment (BMI + LPS). Relative mRNA expression of (A) IL-1β, (B) TNF-α, and (C) IL-8 was analyzed in all the 4 groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were examined with Student’s paired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 was considered to be significant. UN, untreated; BMI, BMI (100 μM) induced for 2 hours; LPS, LPS (1 μg/mL) stimulated for 4 hours; BMI + LPS, BMI (100 μM) induced for 2 hours followed by 4 hours of LPS (1 μg/mL) treatment; NS, not significant.

Discussion

Recently, low grade mucosal inflammation has been reported to be an important factor involved in the pathophysiology of IBS-D.4 Substantial group of evidence suggest that inflammatory mediators modulate intestinal nerve function.25 Alterations in various neurotransmitters are reported in IBS-D patients.7–9 GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter of CNS, regulates various processes in the gut such as motility or cell proliferation.11 In this study we explored the link between inflammation and alteration in levels of GABA during disease conditions. Various proinflammatory cytokines which are hallmarks of inflammation were examined in order to validate the colonic inflammation in IBS-D patients. In vitro studies were done to find out the role of GABA in the modulation of inflammation.

We measured the level of GABA in serum samples of IBS-D patients. A significant reduction was observed in the concentration of GABA in patients as compared to controls. Diminished GABA levels were earlier reported in serum samples of patients suffering from multiple sclerosis, ischemic stroke, ulcerative colitis, and other inflammatory diseases.18,26–28

A functional GABAergic signal system is known to be present in the epithelial cells of the colon.12 We analyzed the expression of various components of the GABAergic signal system in IBS-D. Significant reduction in the expression of GAD2 was observed in IBS-D patients as compared to controls both at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1B and 1H). Expression of GAD1 enzyme could not be determined in the present study. The decrease in GAD may be an important factor for decreased GABA levels in IBS-D patients. GAD activity was reported to be reduced in the serum of patients with multiple sclerosis and ulcerative colitis.26,28 GAD is also reported to play an important role in autoimmune mediated diabetes.29 Interestingly, relative mRNA expression of the GABA degrading enzyme, GABA-T, was also reduced in IBS-D patients. When we looked at the difference between the fold change of GAD and GABA-T reduction, we found that reduction in GAD was 10 times more than the level of reduction in GABA-T. Therefore, we speculated that significant reduction in GAD expression leads to overall reduction of GABA levels in IBS-D patients. Further, we observed elevated levels of GABRP in IBS-D patients. Johnson and Haun30 reported overexpression of GABRP in pancreatic cancer patients and a recent report of Aggarwal et al28 also demonstrated increased expression of GABRP in ulcerative colitis patients. We speculate that in order to compensate for GABAergic signalling which was otherwise compromised due to low levels of GABA, increased expression of GABRP was observed in IBS-D patients.

Relative mRNA expression of both the subunits of GABA-BR, B1, and B2 were also analyzed and found to be downregulated in patients as compared to controls. Brusberg et al31 demonstrated the role of GABA-B receptors in treatment of visceral pain. Visceral pain is the most common symptom of IBS-D patients.32 Coleman et al33 indicated the GABA-BR agonist as a potential therapeutic target for relieving pain in IBS patients. Our results showing reduced expression of both the sub units of GABA-BR further supports the role of GABA-BR in visceral pain in IBS-D patients too. Since inflammation in IBS-D is less predominant as compared to chronic inflammation in ulcerative colitis, we contemplated the role of GABA-BR in pain related behaviour of IBS. There are reports which showed increased expression of GABA-BR in different diseases. A recent report indicated an increased expression of GABA-B2R associated with inhibition of cancer cell proliferation.34 Jiang et al35 reported upregulation in the expression of GABA-BR in gastric and thyroid cancer patients. In this context, our earlier observation revealed increased expression of GABA-B2R in colonic mucosal biopsies of ulcerative colitis patients where inflammation is the predominant feature.28 So this indicates that the function of GABA-BR differs between IBS-D and ulcerative colitis patients.

The expression of the GABA transporter, GAT-2, was increased in IBS-D patients as compared to controls. GAT-2 is responsible for uptake of GABA and thus reduces the local GABA concentration. Expression of GAT-2 was also reported to be upregulated during inflammatory condition in multiple sclerosis patients and ulcerative colitis patients.15 Although this is a first report showing alteration of the GABAergic signal system in IBS-D patients, however, altered expression of GABAergic signal system has been reported during different disease conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, type 1 diabetes, allergic contact dermatitis, experimental autoimmune encephalitis, and ulcerative colitis.18,19, 28, 36–38

Since mild inflammation is involved in the pathogenesis of IBS-D, expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 were determined in IBS-D patients and controls. Significant increase in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in patients was detected. Our observations support the findings by Rana et al4 in serum samples of IBS-D patients. An et al1 also reported increased expression of IL-1β and inducible nitric oxide synthase in colonic mucosa of IBS-D patients. Hence our data further validate the fact that mild inflammation contributes in the pathogenesis of IBS-D.1,2,4

For understanding the role of GABA in gut inflammation, in vitro studies were performed with pre-treatment of GABA to LPS stimulated HT-29 cells, and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α were measured. In order to establish if functional GABAergic signalling is present in HT-29 cells, we tested the expression of GAD in HT-29 cells, where we observed significant change in expression between untreated and LPS treated cells (data not shown).

Prior treatment of GABA to LPS stimulated HT-29 cells showed inhibitory effect of GABA on inflammatory mediators (Fig. 3) indicating anti-inflammatory role of GABA by inhibiting the expression of inflammatory mediators. Han et al23 also observed that GABA can significantly inhibit mRNA expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and inducible nitric oxide synthase in LPS stimulated RAW 264.7 cells.23 It was shown that the treatment of LPS activated peritoneal macrophages (purified from mice) with GABA-AR agonist resulted into decreased production of IL-1β.18 A study conducted by Yang et al39 also suggested that production of TNF-α, decreased in GABA-and topiramate-treated lipid-laden human monocyte-derived macrophages.

We further used the antagonist of GABA-AR, BMI, to treat HT-29 cells in order to warrant the anti-inflammatory role of GABA. It is known that LPS stimulation to HT-29 cells upregulate the expression of inflammatory mediators and therefore, prior treatment with BMI to LPS stimulated HT-29 cells led to further upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines. This substantiated the fact that BMI antagonises the effect of GABA.

From the data on clinical samples, we conclude that diminished GABAergic signalling contributes to the pathophysiology of IBS-D patients. In vitro studies indicate GABA plays an important role in controlling inflammation, and the inhibitory effect of GABA can be blocked by using an antagonist of GABA. Further mechanistic experiments are required to establish the role of GABA in IBS-D and other inflammatory conditions. Therefore, it can be speculated that GABA or GABA agonists may be used in the treatment of IBS-D or other inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgements

We thank the subjects who contributed samples for this study. We also thank Dr Raju Ranjha (National Institute of Malaria Research, New Delhi) for his suggestions in the preparation of the manuscript. Surbhi Aggarwal gratefully acknowledges the research fellowship from University Grants Commission, New Delhi.

Footnotes

Financial support: The current work was financially supported by the Department of Biotechnology, New Delhi DBT grant (No. BT/PR8348/MED/30/1023/2013) awarded to Jaishree Paul. We acknowledge umbrella funding from DST PURSE II: File No. 6(54)/SLS/JP/DST PURSE/2016–17 awarded to Jaishree Paul.

Author contributions: Conceived and designed the experiments: Jaishree Paul and Surbhi Aggarwal; performed the experiments: Surbhi Aggarwal; analyzed the data: Jaishree Paul and Surbhi Aggarwal; contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools: Jaishree Paul; manuscript prepared: Surbhi Aggarwal, Vineet Ahuja, and Jaishree Paul; and clinical samples: Vineet Ahuja.

References

- 1.An S, Zong G, Wang Z, Shi J, Du H, Hu J. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in mast cells contributes to the regulation of inflammatory cytokines in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1083–1093. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes PA, Harrington AM, Castro J, et al. Sensory neuroimmune interactions differ between irritable bowel syndrome subtypes. Gut. 2013;62:1456–1465. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makharia GK, Verma AK, Amarchand R, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a community based study from northern India. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:82–87. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rana SV, Sharma S, Sinha SK, Parsad KK, Malik A, Singh K. Pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine response in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome patients. Trop Gastroenterol. 2012;33:251–256. doi: 10.7869/tg.2012.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cremon C, Gargano L, Morselli-Labate AM, et al. Mucosal immune activation in irritable bowel syndrome: gender-dependence and association with digestive symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:392–400. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brint EK, MacSharry J, Fanning A, Shanahan F, Quigley EM. Differential expression of toll-like receptors in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:329–336. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talley NJ. Serotoninergic neuroenteric modulators. Lancet. 2001;358:2061–2068. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pang X, Boucher W, Triadafilopoulos G, Sant GR, Theoharides TC. Mast cell and substance P-positive nerve involvement in a patient with both irritable bowel syndrome and interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1996;47:436–438. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowell MD. Role of serotonin in the pathophysiology of the irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:1285–1293. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jembrek MJ, Auteri M, Serio R, Vlainic J. GABAergic system in action: connection to gastrointestinal stress-related disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23:4003–4011. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170209155753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyland NP, Cryan JF. A gut feeling about GABA: focus on GABA(B) receptors. Front Pharmacol. 2010;1:124. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2010.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Xiang YY, Lu WY, Liu C, Li J. A novel role of intestine epithelial GABAergic signaling in regulating intestinal fluid secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G453–G460. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00497.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen RW, Sieghart W. GABA a receptors: subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bettler B, Kaupmann K, Mosbacher J, Gassmann M. Molecular structure and physiological functions of GABA(B) receptors. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:835–867. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul AM, Branton WG, Walsh JG, et al. GABA transport and neuroinflammation are coupled in multiple sclerosis: regulation of the GABA transporter-2 by ganaxolone. Neuroscience. 2014;273:24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dionisio L, José De Rosa M, Bouzat C, Esandi Mdel C. An intrinsic GABAergic system in human lymphocytes. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Z, Mendu SK, Birnir B. GABA is an effective immunomodulatory molecule. Amino Acids. 2013;45:87–94. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1193-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhat R, Axtell R, Mitra A, et al. Inhibitory role for GABA in autoimmune inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:2580–2585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915139107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley JM, Hughes LB, Bridges SL., Jr Does gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) influence the development of chronic inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis? J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winzen R, Kracht M, Ritter B, et al. The p38 MAP kinase pathway signals for cytokine-induced mRNA stabilization via MAP kinase-activated protein kinase 2 and an AU-rich region-targeted mechanism. EMBO J. 1999;18:4969–4980. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka T, Kai S, Matsuyama T, Adachi T, Fukuda K, Hirota K. General anesthetics inhibit LPS-induced IL-1beta expression in glial cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han D, Kim HY, Lee HJ, Shim I, Hahm DH. Wound healing activity of gamma-aminobutyric Acid (GABA) in rats. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;17:1661–1669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes PA, Zola H, Penttila IA, Blackshaw LA, Andrews JM, Krumbiegel D. Immune activation in irritable bowel syndrome: can neuroimmune interactions explain symptoms? Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1066–1074. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demakova EV, Korobov VP, Lemkina LM. [Determination of gamma-aminobutyric acid concentration and activity of glutamate decarboxylase in blood serum of patients with multiple sclerosis]. Klin Lab Diagn. 2003:15–17. [Russian] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosinian M, Qujeq D, Ahmadi Ahangar A. The relation between GABA and L-arginine levels with some stroke risk factors in acute ischemic stroke patients. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2016;5:100–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aggarwal S, Ahuja V, Paul J. Attenuated GABAergic signaling in intestinal epithelium contributes to pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2768–2779. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4662-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jun HS, Khil LY, Yoon JW. Role of glutamic acid decarboxylase in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1892–1901. doi: 10.1007/PL00012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson SK, Haun RS. The gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor pi subunit is overexpressed in pancreatic adenocarcinomas. JOP. 2005;6:136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brusberg M, Ravnefjord A, Martinsson R, Larsson H, Martinez V, Lindstrom E. The GABA(B) receptor agonist, baclofen, and the positive allosteric modulator, CGP7930, inhibit visceral pain-related responses to colorectal distension in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salari P, Abdollahi M. Systematic review of modulators of benzodiazepine receptors in irritable bowel syndrome: is there hope? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4251–4257. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i38.4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman N, Spiller R. New pharmaceutical approaches to the treatment of IBS: future development & research. Ann Gastroenterol. 2002;15:278–289. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang X, Zhang R, Zheng Y, et al. Expression of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors on neoplastic growth and prediction of prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl Med. 2013;11:102. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang X, Su L, Zhang Q, et al. GABAB receptor complex as a potential target for tumor therapy. J Histochem Cytochem. 2012;60:269–279. doi: 10.1369/0022155412438105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oresic M, Simell S, Sysi-Aho M, et al. Dysregulation of lipid and amino acid metabolism precedes islet autoimmunity in children who later progress to type 1 diabetes. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2975–2984. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nigam R, El-Nour H, Amatya B, Nordlind K. GABA and GABA(A) receptor expression on immune cells in psoriasis: a pathophysiological role. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:507–515. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duthey B, Hübner A, Diehl S, Boehncke S, Pfeffer J, Boehncke WH. Anti-inflammatory effects of the GABA(B) receptor agonist baclofen in allergic contact dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:661–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y, Lian YT, Huang SY, Cheng LX, Liu K. GABA and topiramate inhibit the formation of human macrophage-derived foam cells by modulating cholesterol-metabolism-associated molecules. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;33:1117–1129. doi: 10.1159/000358681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]