Introduction

In 2013, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Kcentra® (CSL Behring GmbH, Kankakee, IL, USA), for the urgent reversal of acquired coagulation factor deficiency induced by vitamin K antagonist therapy (e.g. warfarin) in adult patients with acute major bleeding or need for urgent surgery/invasive procedure. This four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (4F-PCC) contains coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X, proteins C and S, antithrombin III and human albumin. The dose is expressed as units of factor IX activity. When used to reverse the anticoagulant effects of warfarin, an individualised dose should be determined based on body weight and degree of anticoagulation determined by the current international normalised ratio (INR)1.

Unlike warfarin, the factor Xa (FXa) inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban) do not have an FDA-approved antidote or reversal agent1–4. Current guidelines only provide recommendations for the reversal of the effects of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in the setting of an intracranial haemorrhage, and there are limited data on the safety and efficacy of the use of clotting factors such as Kcentra® for life-threatening bleeding or urgent reversal for invasive surgical procedures1,5,6. Despite the low quality of evidence, the Neurocritical Care Society and the Society of Critical Medicine suggest administration of a 4F-PCC or activated PCC if intracranial haemorrhage occurs within three to five terminal half-lives of drug exposure or in the context of liver failure. There is limited published literature, beyond case reports or case series, on the effect of three-factor PCC on haemostasis in patients on DOACs and these concentrates are not, therefore, recommended6. More data are available for haemostasis in patients experiencing major bleeding while on vitamin K antagonists, but considering that the mechanisms of action of these two classes of medications are different, extrapolation of efficacy data is difficult.

In the absence of large, randomised clinical trials, current data suggest that 4F-PCC can be utilised to reverse the effects of DOACs7–11.

In a randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover study 12 healthy male volunteers received rivaroxaban 20 mg twice daily or dabigatran 150 mg twice daily for 2.5 days and were then exposed to a single bolus of 50 units/kg of 4F-PCC or a similar volume of saline. After a wash-out period, the procedure was repeated with the other anticoagulant. Rivaroxaban caused significant prolongation of the prothrombin time which was immediately and completely reversed by 4F-PCC. Additionally, the endogenous thrombin potential was inhibited by rivaroxaban and normalised by 4F-PCC. In the dabigatran samples, activated partial thromboplastin time, ecarin clotting time, and thrombin time were increased and remained elevated after administration of 4F-PCC7.

An additional study retrospectively evaluated the safety and efficacy of 4F-PCC administration in the reversal of coagulopathy mediated by rivaroxaban (n=16) or apixaban (n=2) in the setting of spontaneous intracranial haemorrhage. Dosing of 4F-PCC was based on the manufacturer’s recommendation for reversal of vitamin K antagonists, taking into account presenting INR and body weight. One patient had progressive haemorrhage and another experienced a thromboembolic event. Study investigators noted a potential reduction in haemorrhagic complications and haematoma expansion in patients presenting with traumatic and spontaneous intracranial haemorrhages. Favourable outcomes, as defined by the study investigators, were observed in six of the 18 patients (33%) while six patients died in hospital8.

Durie and colleagues reported on the use of 4F-PCC in a 60-year old male who was anticoagulated with apixaban prior to being admitted with blunt abdominal trauma and haemodynamic instability secondary to a motor vehicle collision. In the trauma admitting area, the patient received 4 units of packed red blood cells and was taken emergently to the operating room where he was resuscitated with 5 litres of crystalloid, 10 additional units of packed red blood cells, 6 units of fresh frozen plasma, 2 units of platelets, 1.25 litres of cell saver and 5,000 units of 4F-PCC. Although haemoglobin, haematocrit, and platelet counts remained stable until day 3, the patient continued to require transfusions due to symptomatic blood loss and ultimately died on day 49.

Edoxaban is the most recently approved FXa inhibitor; however, early trials already suggest that its effects can be reversed by 4F-PCC3,10. In a phase I study, a single 60 mg dose of edoxaban was administered to 110 patients followed by 50 units/kg, 25 units/kg, or 10 units/kg of 4F-PCC. Punch biopsies were used to determine a dose-dependent reversal of edoxaban’s anticoagulation effect. Complete reversal, with regards to bleeding duration, bleeding volume and endogenous thrombin potential, was achieved with PCC 50 units/kg. Complete reversal was not noted for prothrombin time10.

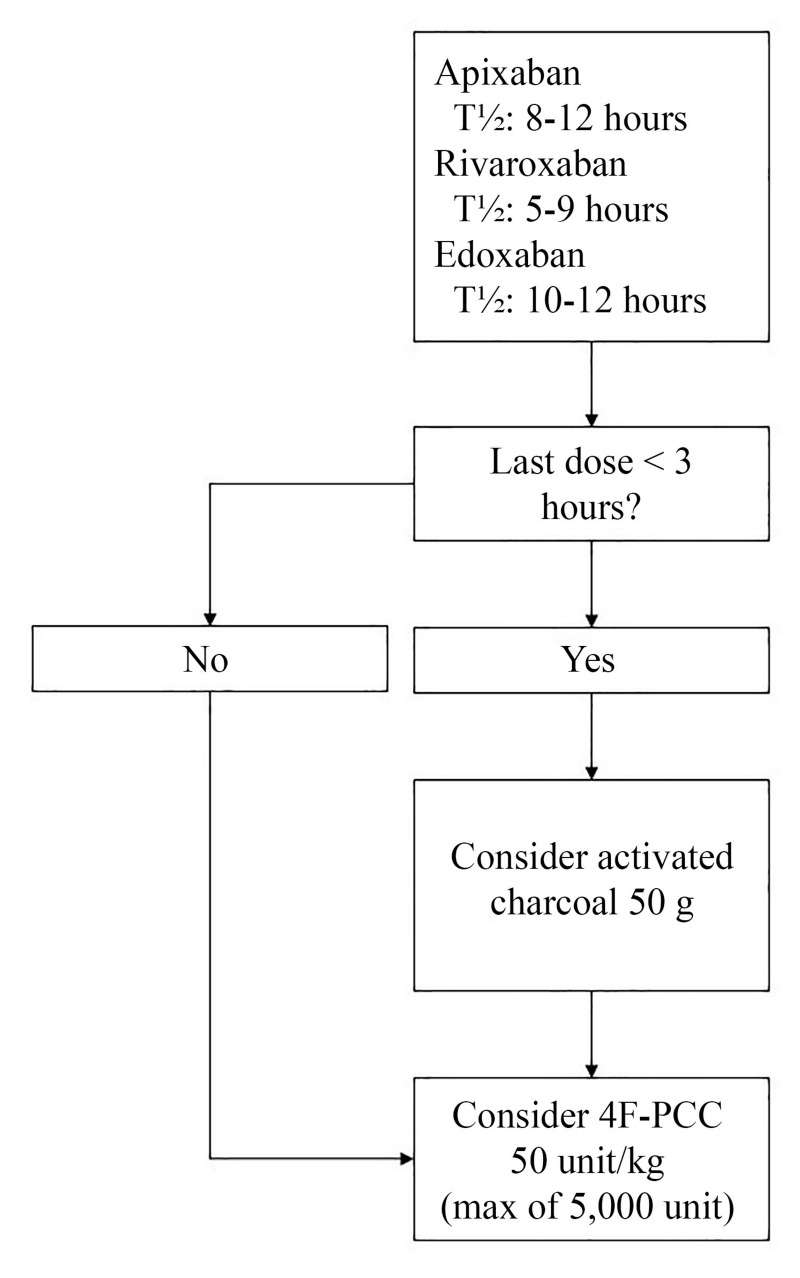

Based on available data, an institutional protocol has been designed for emergency reversal of oral FXa inhibitors (Figure 1). The recommended dose of 4F-PCC for reversal is 50 units/kg. Reversal of dabigatran with 4F-PCC is not recommended based on conflicting data7. The objective of this review is to characterise the current use of 4F-PCC and determine adherence to institutional recommendations.

Figure 1.

Factor Xa inhibitor reversal algorithm.

Materials and methods

This chart review was conducted at a 489-bed community hospital. Data collection began in January of 2014 when 4F-PCC was added to the study institution’s formulary. Use of 4F-PCC has been monitored on a biweekly basis in order to improve appropriate utilisation and policies and procedures regarding drug dispensing and administration. All patients who received 4F-PCC for reversal of a FXa inhibitor were included in the evaluation. Patients requiring reversal due to warfarin or dabigatran therapy were not included. An electronic medical record was used to collect each patient’s data. Appropriate utilisation of 4F-PCC was based on recommendations approved by the study institution’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. The Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) classification was used to estimate blood loss before 4F-PCC administration12. Bleeding was classified in accordance with International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) bleeding definitions13.

Results

A total of 29 bleeding events involving 28 unique patients who received 4F-PCC for reversal of a FXa inhibitor from January 2014 to April 2016 were included (Table I). One patient presented twice with a major bleeding event on two separate occasions during the study period. More bleeding events were reversed in patients receiving rivaroxaban (62.1%) than apixaban (37.9%). The most common indication for anticoagulation was prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Most patients given 4F-PCC for the reversal of the effects of DOACs presented with a major bleeding event (89.7%) while only two patients were given reversal treatment for emergency surgery (Table II). The gastrointestinal tract was the most common source of bleeding. Twenty patients (69%) had 4F-PCC administered while in the Emergency Department.

Table I.

Patients’ characteristics.

| Characteristics | Patient admissions (n=29) |

|---|---|

| Age, average years | 72.7 |

|

| |

| Female, n (%) | 14 (48.3) |

|

| |

| Length of stay, average days | 5.3 |

|

| |

| Concomitant antiplatelet, n (%) | 12 (41.4) |

|

| |

| DOAC, n (%) | |

| Apixaban | 11 (37.9) |

| Rivaroxaban | 18 (62.1) |

|

| |

| Indication for anticoagulation, n (%) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 20 (69) |

| Other | 2 (6.9) |

| Bioprosthetic valve | 1 (3.4) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 7 (24.1) |

|

| |

| Hemoglobin before 4F-PCC, average (g/dL) | 9.27 |

|

| |

| ATLS blood loss, n (%) | |

| Class I | 21 (72.4) |

| Class II | 8 (27.6) |

|

| |

| ISTH bleeding, n (%) | |

| Major | 26 (89.7) |

| Clinically relevant, non-major bleeding | 1 (3.4) |

| Not applicable | 2 (6.9) |

|

| |

| Discharge disposition, n (%) | |

| Died | 6 (20.7) |

| Home | 12 (41.4) |

| Home with home health assistance | 2 (6.9) |

| Nursing home/long-term care facility | 4 (13.8) |

| Rehabilitation/skilled nursing facility | 5 (17.2) |

| Transfer | 0 |

|

| |

| DOAC continued at discharge | |

| No | 24 (82.8) |

| Yes | 4 (13.8) |

| Switched to another DOAC | 1 (3.4) |

DOAC: direct oral anticoagulant; 4F-PCC: four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate; ATLS: Advanced Trauma Life Support; ISTH: International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

Table II.

Characteristics of the bleeding events.

| Characteristics | Patient admissions (n=29) |

|---|---|

| 4F-PCC ordered in the ED, n (%) | 20 (69) |

|

| |

| Indication for 4F-PCC, n (%) | |

| Emergent surgery | 3 (10.3) |

| Gastrointestinal bleed | 17 (58.6) |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 6 (20.7) |

| Intraperitoneal bleed | 1 (3.4) |

| Non-critical site | 1 (3.4) |

| Retroperitoneal bleed | 1 (3.4) |

|

| |

| Appropriate dose, n (%) | 22 (75.9) |

|

| |

| Inappropriate dose, n (%) | 7 (24.1) |

| Dose too low | 7 (100) |

|

| |

| Received fresh frozen plasma, n (%) | 4 (13.8) |

|

| |

| Received packed red blood cells, n (%) | 22 (75.9) |

|

| |

| Received phytonadione, n (%) | 10 (34.5) |

|

| |

| Received platelets, n (%) | 4 (13.8) |

DOAC: direct oral anticoagulant; ED: Emergency Department.

One patient experienced a thromboembolic event (right leg deep vein thrombosis) 15 days after receiving 4F-PCC. The patient had been admitted with a subdural haematoma while being treated with rivaroxaban for a left leg deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. An inferior vena cava filter was placed and anticoagulation was not continued after 4F-PCC administration. A direct relationship between administration of 4F-PCC and the thromboembolic event is difficult to establish due to the retrospective nature of the review.

Of the six patients in the evaluation who died, two presented for emergency surgery (septic state following an above the knee amputation requiring revision and duodenal perforation secondary to a malpositioned gastrotomy tube), three with an intracranial haemorrhage, and one with an intraperitoneal bleed (identified during the work-up for a cardiopulmonary arrest). Of the three patients whose deaths were not directly attributable to bleeding complications, one was transferred to the study centre in cardiac arrest with severe anaemia secondary to an intraperitoneal bleed. This patient then received 4F-PCC and underwent exploratory laparotomy and haemostasis was established; however, care was subsequently withdrawn on day 3 due to anoxic brain injury and poor prognosis. A second patient died secondary to Gram-negative sepsis with multi-organ failure after undergoing a below the knee amputation and a subsequent above the knee amputation secondary to sepsis and gangrene associated with left foot cellulitis and osteomyelitis. This patient had received 4F-PCC prior to emergency surgery for the revision of ongoing necrosis in the setting of anticoagulation with apixaban. The third patient presented with a minor gastrointestinal bleed secondary to a migrated gastrostomy tube which resulted in a perforated duodenum and was administered 4F-PCC to aid in establishing haemostasis for exploratory laparotomy; however, the patient later expired due to respiratory failure and care was withdrawn.

Twelve patients (41.4%) were discharged home and another two patients (6.9%) were discharged home with home health assistance. All four patients who were discharged to a nursing home or long-term care facility had previously presented from a nursing home or long-term care facility and did not require an increased level of care. Of the five patients who were discharged to a rehabilitation facility or skilled nursing facility, one came from a facility of equal level of care, one came from a nursing home and was discharged to a rehabilitation facility, and the remaining three patients presented from home.

Of the 29 bleeding events, 24 patients (82.8%) did not have DOAC therapy continued at discharge, four patients (13.8%) resumed their prior anticoagulant therapy, and one patient (3.4%) was switched to an alternative DOAC. Of the five patients who resumed anticoagulation at discharge, four had presented with major bleeding. One patient on rivaroxban was transitioned to apixiban. One patient on apixiban was discharged on the same anticoagulant. Two patients on rivaroxban were subsequently discharged on rivaroxaban. One patient with clinically relevant, non-major bleeding presented on rivaroxaban and was discharged on rivaroxaban. The patient who received 4F-PCC twice was re-initiated on rivaroxaban at her nursing home despite discharge orders specifying that anticoagulation should not be resumed.

Discussion

Rivaroxaban was the first oral FXa inhibitor approved by the FDA and has the most available data to support the use of 4F-PCC as a reversal agent4,6,7,11. One retrospective review considered 25 patients who experienced a haemorrhage while on dabigatran (n=18) or rivaroxaban (n=7). Three patients had a minor haemorrhage, seven had a major haemorrhage, and 15 had a life-threatening haemorrhage. The average age of these patients was 77 years and most were on a DOAC for prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. The majority of patients (81%) were admitted because of a gastrointestinal bleed (13 patients on dabigatran and 4 on rivaroxaban). Fifty-six percent of the patients were administered packed red blood cells and 28% were administered fresh-frozen plasma, being given a median of 4.5 and 6 units, respectively. Six patients also received phytonadione. Three patients previously taking rivaroxaban (1 major bleed and 2 life-threatening bleed) received three-factor PCC at a median dose of 40 units/kg11.

Based on such previously published literature and clinical experience, the study site does not recommend utilising 4F-PCC to reverse dabigatran7. The results of this evaluation are consistent with other reports, with rivaroxaban being the most commonly reversed FXa inhibitor. Consistent with other studies, patients in this evaluation also received adjunctive therapies such as packed red blood cells (75.9%), fresh frozen plasma (13.8%), and phytonadione (34.5%)11. It is important to note that administration of phytonadione for reversal of FXa inhibitors is not recommended2–4.

The retrospective design of this study limited the ability to collect information regarding important clinical outcomes as well as follow-up of the patients treated with 4F-PCC. The lack of a control group for comparison is also a limitation of internal validity in the study, as is potential confounding from adjunctive therapies that may have contributed to haemostasis in the study. Another potential confounder to be considered is that the timing of the administration of the last DOAC dose to administration of 4F-PCC could not be accounted for in the retrospective nature. A prospective trial design was not feasible given the low rate of accrual of patients and the lower rates of major bleeding associated with some of the FXa inhibitors as compared with warfarin. Additionally, the low rate of major bleeds that were not reversed with 4F-PCC make any statistical comparisons impractical. Finally, although a standardised institutional algorithm was developed, off-algorithmic use of 4F-PCC was noted in the study sample in addition to adjunctive therapies that may have played some role in establishing haemostasis.

Conclusions

The current study characterises the potential safety of 4F-PCC for use in achieving haemostasis in patients with major bleeding; however, future studies are warranted and should investigate the efficacy and safety of reversal of FXa inhibitors with 4F-PCC. Despite limited guidance from key clinical societies, 4F-PCC should be considered in patients who present with major bleeding from DOAC therapy and who are known to have been recently administered DOAC therapy and have no contraindications to 4F-PCC use.

Footnotes

Authorship contributions

NSB, KBT and BML conceived the study and designed the trial. KBT collected and managed the data, while NSB and BML supervised data collection and provided advice. All Authors provided advice on the study design and data analysis, drafted the manuscript, and contributed substantially to its revision. All Authors take responsibility for the paper as a whole.

The Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kcentra® (Prothrombin Complex Concentrate [Human]) package insert. Kankakee, IL: CSL Behring LLC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eliquis® (apixaban) tablets [prescribing information] Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savaysa® (edoxaban) tablets [prescribing information] Parsippany, NJ: Daiichi Sankyo, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xarelto® (rivaroxaban) tablets [prescribing information] Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, et al. Oral anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e44S–88S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frontera JA, Lewin JJ, 3rd, Rabinstein AA, et al. Guideline for reversal of antithrombotics in intracranial hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and Society of Critical Care Medicine. Neurocrit Care. 2016;24:6–46. doi: 10.1007/s12028-015-0222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, et al. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124:1573–79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grandhi R, Newman WC, Zhang X, et al. Administration of 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate as an antidote for intracranial bleeding in patients taking direct factor Xa inhibitors. World Neurosurg. 2015;84:1956–61. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durie R, Kohute M, Fernandez C, Knight M. Prothrombin complex concentration for the management of severe traumatic bleeding in a patient anticoagulated with apixaban. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41:92–93. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zahir H, Brown KS, Vandell AG, et al. Edoxaban effects on bleeding following punch biopsy and reversal by a 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate. Circulation. 2015;131:82–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pahs L, Beavers C, Schuler P. The real-world treatment of hemorrhages associated with dabigatran and rivaroxaban: a multicenter evaluation. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2015;14:53–61. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0000000000000042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kortbeek JB, Al Turki SA, Ali J, et al. Advanced trauma life support, 8th edition, the evidence for change. J Trauma. 2008;64:1638. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181744b03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaatz S, Ahmad D, Spyropoulos AC, Schulman S. Definition of clinically relevant non-major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non-surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:2119–26. doi: 10.1111/jth.13140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]