Abstract

Stable carbon (13C) and nitrogen isotopes (15N) are useful tools in determining the presence of agricultural influences in freshwater ecosystems. Here we examined δ15N and δ13C signatures in nitrate, fish, and mussel tissues, from rivers in Southern Ontario, Canada, that vary in their catchment proportion of agriculture land use, nutrients and organic matter quality. We found comparatively 15N-enriched δ15N values in animal tissues and dissolved nitrates, relative to expected values characterized by natural sources. We also observed a strong, positive correlation between riparian agriculture percentages and δ15N values in animal tissues and nitrates, indicating a significant influence of agricultural land use and the probable dominance of organic fertilizer and manure inputs in particular. The use of a 15N-based equation for the estimation of fish trophic position confirmed dietary analyses is showing all fish species to be tertiary consumers, with a relatively consistent 15N-enrichment in animal tissues between trophic levels. This indicates that variability in 15N-trophic fractionation is minor, and that fish and mussel tissue δ15N values are largely representative of source nitrogen. However, the trophic fractionation value varied from accepted literature values, suggesting strong influences from either local environmental conditions or dietary variation. The δ13C datasets did not correlate with riparian agriculture, and animal δ13C signatures in their tissues are consistent with terrestrial C3 vegetation, suggesting the dominance of allochthonous DOC sources. We found that changes in water chemistry and dissolved organic matter quality brought about by agricultural inputs were clearly expressed in the δ15N signatures of animal tissues from all trophic levels. As such, this study confirmed the source of anthropogenic nitrogen in the studied watersheds, and demonstrated that this agriculturally-derived nitrogen could be traced with δ15N signatures through successive trophic levels in local aquatic food webs. The δ13C data was less diagnostic of local agriculture, due to the more complex interplay of carbon cycling and environmental conditions.

Introduction

Agricultural land use can significantly impact the health and functioning of aquatic ecosystems through increased inputs of organic material, use of organic and chemical fertilizers, and downstream eutrophication [1, 2]. Agricultural fertilizers can often be traced chemically through food webs, given knowledge of uptake pathways and mechanisms of chemical processing, as the signatures of these inputs are transferred from baseline primary producers to higher-level consumers. As such, stable isotopes provide a particularly useful tool to track the presence of agricultural nutrients in local food webs.

Stable nitrogen and carbon isotopes (15N and 13C) can be traced across successive trophic levels, allowing for the elucidation of potentially cascading influences of human land use through aquatic ecosystems [3, 4]. A number of studies have utilized δ13C and δ15N data to investigate the movement of nitrogen and carbon through food chains [5–9], or used such data to discern agricultural influences in the δ15N signatures of aquatic biota [3, 4, 10, 11]. Many of these have compared the tissue stable isotope signatures of animals in higher trophic levels to those obtained from baseline consumers, in order to investigate the movement of nitrogen and carbon through food chains.

In aquatic systems dominated by anthropogenic influences, strong correlations are typically found between the δ15N signatures of tissues from both primary and secondary consumers, with agricultural variables such as land-use percentages and fertilizer and manure nitrogen loadings [4, 12]. Other research showed that these agricultural influences could also be traced upwards through successive trophic levels. For example, δ15N values from primary consumers are tracked to higher-level consumers with a consistent isotope fractionation of about 3.4‰ or less between each level [9]. This 15N-fractionation of 3.4‰ has since been considered as a relatively consistent and reliable value that has been applied to subsequent studies.

Past work has also tried to clarify the influences of agriculture on the δ13C signatures of biota, and have attempted to trace these influence through aquatic food webs. This has proven more difficult as the δ13C of organic fertilizers and manure are indistinguishable from those of natural or cropland plant material, since the latter is often the primary source of the former. Previous work has instead attempted to differentiate between terrestrial and autochthonous carbon sources within river waters, given that aquatic primary producers often have comparatively lower δ13C values as compared to those derived from terrestrial soils or plant matter. While attempts have also been made to quantify trophic fractionation of 13C across multiple trophic levels, these have encountered far more variation than that observed with 15N. For example, a study by Post found δ13C fractionation values averaging around 0.4 ± 1.3‰ between successive trophic level [9].

This wide range of values may be due to variation within animal species in the same locations. This was found by Hesslein et al. [13], which measured δ13C differences of up to 7‰ between individuals of the same Lake Trout species, with trophic fractionation values that appeared to be contrary to the expected trend: trout species were found to have lower δ13C values than white suckers, which should occupy a lower trophic level. Clearly, the trophic fractionation behavior of δ13C in aquatic ecosystems remains uncertain, and there exists a knowledge gap that needs to be addressed.

A number of studies have utilized δ13C and δ15N data to investigate the movement of nitrogen and carbon through food chains[5–9], or used such data to discern agricultural influences in the δ15N signatures of aquatic biota[3, 4, 10, 11]. Many of these have compared the tissue stable isotope signatures of animals in higher trophic levels to those obtained from baseline consumers and dissolved nitrates, in order to investigate the movement of nitrogen and carbon through food chains [9]. However, few of these previous studies directly linked land use to 15N-fractionation in nitrate and food webs, or examined both δ13C and δ15N along a gradient of agricultural land use. Even fewer have been truly comprehensive by not only comparing δ15N and δ13C data from consumers in two trophic levels, but also including data from primary producers and dissolved nitrate. Here we address this paucity of information by analyzing the δ13C and δ15N of dissolved nitrate, periphyton, mussel and fish tissue to provide a comprehensive study of trophic isotope fractionation and the effects of an agricultural land use gradient on isotope systematics.

In this work, we assessed how accurately δ13C and δ15N signatures in primary producers and consumers at higher trophic levels reflect the nature of agricultural inputs into aquatic food webs, and how these values vary with an agriculture land use gradient. As well, this study determined if the isotopic fractionation at each trophic level (including between primary producers and primary consumers) is truly consistent. Concurrently, the results will trace the dominant source of anthropogenic nitrogen and carbon in the studied watersheds, and confirm if higher trophic levels are indeed effective indicators of such human-derived nutrient inputs.

Methods

Study sites

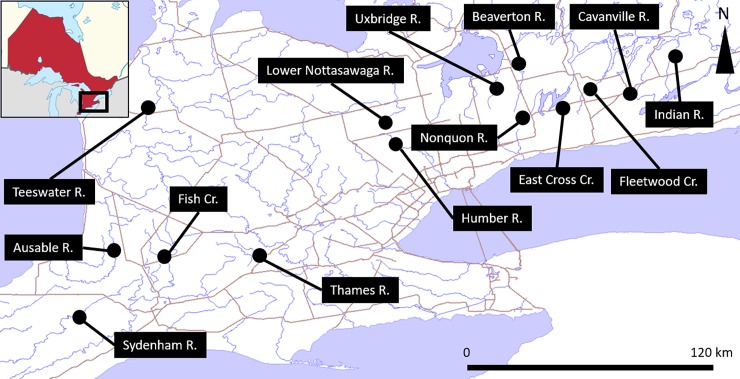

Fourteen streams in Southern Ontario, Canada, were sampled for water chemistry, mussels, fish and stable isotopes (Fig 1). These streams range in the proportion of cropland in their catchment and have been previously studied to investigate the effects of agriculture on a range of ecosystem responses (e.g., [14–17]). Each watershed varies in catchment area and degree of agriculture land use, with total riparian monoculture (row cropping) making up 8% to 50% of basin surface areas, total catchment cropland making up 18% to 59% of catchment areas, and total catchment areas ranging from 2.9 to 498 km2 [18]. The remainder of the land cover is mostly comprised of woodland and wetlands. Corn is the dominant crop type in each basin, with barley, canola, alfalfa, oats, soybeans, wheat, and other legumes present in lesser quantities [19].

Fig 1. Map of all sampling locations.

Basemap data from the Ontario Government, via ESRI Canada.

Sample collection

Water and animal tissue samples were collected from each stream under baseflow conditions over the period of August 8 to 17 of 2012. We selected this timeframe to avoid confounding effects of lagged isotopic signals from spring fertilizer applications and novel dietary changes associated with Rock Bass, Brook Trout, and Brown Trout spawning. All sampling occurred on waterways accessed through public access points and no prior permission was required. At each location, 20 L of water were collected at the stream thalweg and stored on ice for later laboratory processing for nutrient and carbon analyses. Site-specific water quality was assessed using an HQ30d portable oxygen and temperature meter and YSI-30 conductivity meter.

Fish were collected using an LR-24 backpack electroshocker and dip nets, in accordance with the Ontario Stream Assessment Protocol ([20], permit MNR 51943). Upon capture, all fish were measured for length and weight, and classified as the following species: Johnny Darters (Etheostoma nigrum), Greenside Darters (Etheostoma blennioides), Rock Bass (Ambloplites rupestris), Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis), and Brown Trout (Salmo trutta) (the latter three being grouped as “large fish”). Four individuals of 1 to 3 species per stream were euthanized via the application of blunt force in order to avoid tissue contamination associated with the use of chemical agents. The euthanization method was approved by the Trent University Animal Care Committee (ACC), following the submission of an Animal Care Protocol Application. All specimens were later frozen for isotopic analyses of muscle tissue. Gut contents of four to five individuals of bass and trout species from each site were examined to identify dominant food sources. Smaller-sized darters were too small for such an examination (the bulk of the tissue being required for isotopic analyses).

We focused our study on mussels of two common species, Elliptio complanata and Lasmigona costata. These mussels were located based on site recommendations from a previous 2008 collection as in Spooner et al. (2013) [18, 21]. All field staff received intensive training to recognize all local mussel species, including those listed as threatened, endangered, or at-risk as per Ontario’s Endangered Species Act. If a listed species was found, field staff was instructed to refrain from picking it up and GPS coordinates were reported to the appropriate authorities. If mussels of species Elliptio complanata and Lasmigona costata were available in the stream, four of each species were collected by hand and placed on ice prior to transport to the lab. Once in the lab, mussels were dissected to obtain a sample of mantle tissue and were subsequently frozen prior to isotope analyses.

In addition, for each mussel sampled, a nearby rock within 0.5 to 1 m distance was randomly selected for periphyton samples either upstream or downstream of the mussel. Both the mussel shells and rock samples were placed into Ziploc bags filled with 125 ml of distilled water before being gently scrubbed of all surface material. The resulting slurries were washed with diluted hydrochloric acid to remove carbonate, before being passed through a GF/F filter (size 0.7 μm) to collect periphyton for stable isotope determinations.

Laboratory and stable isotope analyses

We analyzed the water samples for dissolved nitrate δ15N, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations, total dissolved nitrogen (TDN), and total dissolved phosphorus (TDP). Water collected in the field was immediately filtered upon arrival to the lab through a 0.22 μm pre-rinsed polycarbonate filter for DOC, TDN and TDP analyses. TDN and TDP were both determined by colorimetry with a Varian Cary 50 Bio UV/Visible Spectrophotometer [14]. Water for δ15NNO3 measurements was prepared using the LINX II protocol [22].

All samples were filtered through a 0.2 μm filter, with the dissolved nitrate being converted to ammonium and diffused onto an acidified filter for δ15N analyses. The instrument was calibrated with reference material USGS40 for all δ15N and δ13C measurements every 20 samples, with an internal standard DG (A1) being used for data normalization. All stable isotope samples were analyzed with an EuroEA3028-HTEuroVector Elemental Analyzer (EuroVector SpA, Milan, Italy) coupled with a Micromass IsoPrime Continuous Flow Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (Micromass, UK, with USGS40 standards δ15N = 4.56‰; δ13C = 26.39‰) [18]. Standard deviations for all δ15N and δ13C measurements were < 0.5‰.

The same instrumentation was utilized for animal tissue (mussels and fish) and periphyton δ15N and δ13C analyses, following the method of [23], prior to which samples were dried and ground into powder. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations were measured with an OI Analytical 1030D Total Organic Carbon analyzer.

Stable isotope fractionation estimates

In order to determine the extent to which variability in trophic 15N-fractionation could affect fish tissue values, and whether such variation is strong between the sites of study, we estimated trophic 15N-fractionation values at all sites with the following formula modified from [7]:

| (1) |

In Eq (1), “λ” represents the trophic position of the organism used to determine “δ15Nbase” (i.e., the baseline trophic δ15N value) and “Δn” is the assumed 15N enrichment between each trophic level. The δ15N values of mussel tissue were used for δ15Nbase, with the corresponding λ being 2 (i.e., primary consumers). Based on the observed fish gut contents, which were exclusively composed of invertebrate species and devoid of smaller fish types in the bass and trout samples, we assumed that all fish were tertiary consumers and a trophic level of “3” was used.

Statistical analyses

TDN, TDP, and DOC did not meet normality assumptions, and were therefore log-transformed prior to statistical analyses. Across all study sites, we first performed principal component analyses (PCA) using the R statistical software suite (R Development Core Team) to reduce our exploratory dataset [24] and discern any relationships that may exist between a number of key biological and chemical parameters. The PCA we performed used varimax rotation, which results in a new set of components known as varifactors (VF). The correlations between the input variables and the varifactors (termed “loadings”) can then be used to determine significant relationships amongst multiple parameters of interest.

Following [25], we first applied a PCA to land use/land cover percentages (LULC; wetlands, woods, cultivation, developed land, and miscellaneous) in order to integrate all land-use data into a single PCA axis for comparison to all other variables. From this PCA, the VF loadings thought to correspond to agricultural land-use was extracted. These were then incorporated into a second PCA incorporating physico-chemical variables such as TDN, TDP, water temperature, conductivity, dissolved oxygen (DO), δ13C signatures of fish tissues, and the δ15N signatures of nitrate and all fish tissues and periphyton (mussel stable isotope data was omitted due to a lack of completeness for a feasible PCA).

In both PCA analyses, variable loadings of 0.5 and higher were considered significant while those lower than 0.5 were assumed to be insignificant and were omitted from discussion (following [26]). We subsequently performed univariate linear regressions of physicochemical data against the land-use VF loadings based on the results of the LULC PCA.

Results

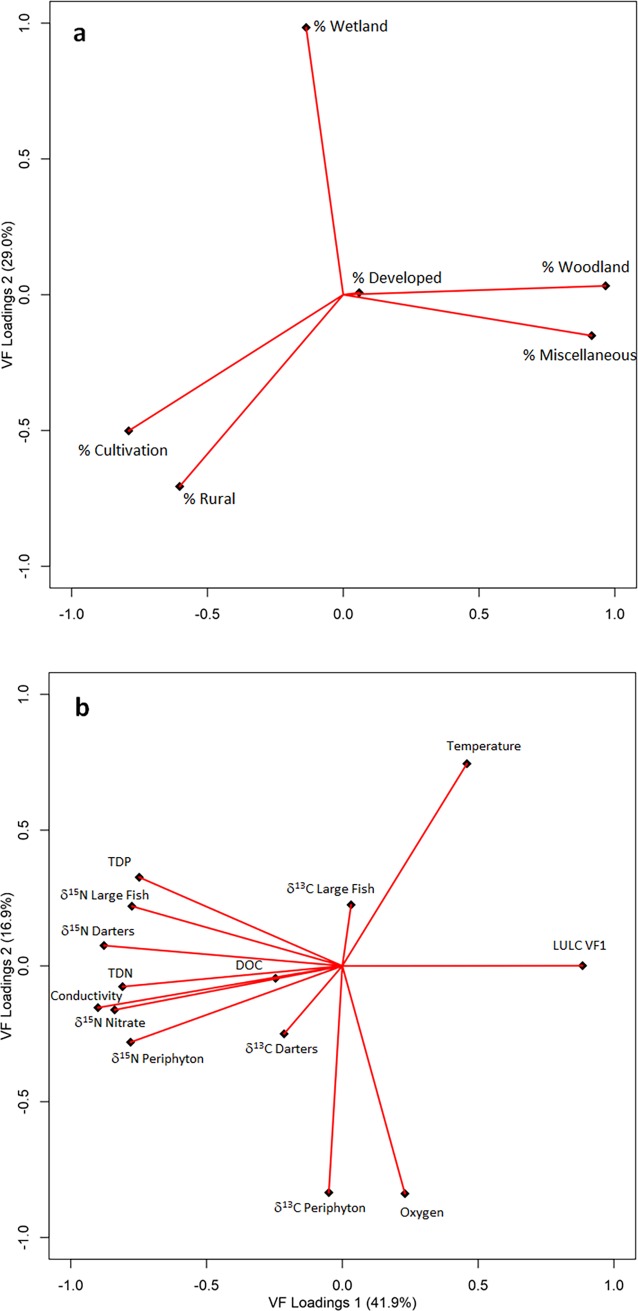

We extracted 2 varifactors with the LULC PCA analysis, corresponding to 75% of the total variance. Based on this determination, the first varifactor (46.3% of total variance) included strong positive loadings by % cultivation and % rural land, along with a strongly negative loading by % woodland and % miscellaneous (Table 1, Fig 2A). This association suggests a strong association of the first varifactor (LULC VF1) with agricultural land use. Two varifactors were also extracted from the second PCA (with incorporation of LULC VF1 as a variable), which accounted for 58.8% of total variance (Fig 2B). In the first varifactor (41.9% of total variance), strong positive loadings by TDP, TDN, conductivity and all δ15N datasets were associated with a significantly negative loading by LULC VF1 (Table 1; Fig 2B). The strong relationship between LULC VF1 and the δ15N datasets with TDN, TDP, and conductivity is indicative of the influence of agricultural land-use.

Table 1. Significant PCA results from both the initial LULC PCA and follow-up physico-chemical PCA (with LULC VF1 as a parameter) on selected site parameters.

| Variables | VF1 | VF2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LULC PCA | % Woodland | 0.97 | |

| % Wetland | -0.14 | 0.98 | |

| % Cultivation | -0.79 | -0.50 | |

| % Developed | |||

| % Rural | -0.60 | -0.71 | |

| % Miscellaneous | 0.92 | -0.15 | |

| Physco-chemical PCA | TDN | -0.81 | |

| TDP | -0.75 | 0.33 | |

| DOC | -0.25 | ||

| Temperature | 0.46 | 0.75 | |

| Conductivity | -0.90 | -0.15 | |

| Oxygen | 0.23 | -0.84 | |

| δ 15N Nitrate | -0.84 | -0.16 | |

| δ 13C Darters | -0.21 | -0.25 | |

| δ 13C Large Fish | 0.23 | ||

| δ 15N Darters | -0.88 | ||

| δ 15N Large Fish | -0.78 | 0.22 | |

| δ 15N Periphyton | -0.78 | -0.28 | |

| δ 13C Periphyton | -0.84 | ||

| LULC VF1 | 0.88 |

Fig 2.

PCA plots utilizing LULC data (a) and physico-chemical data (b).

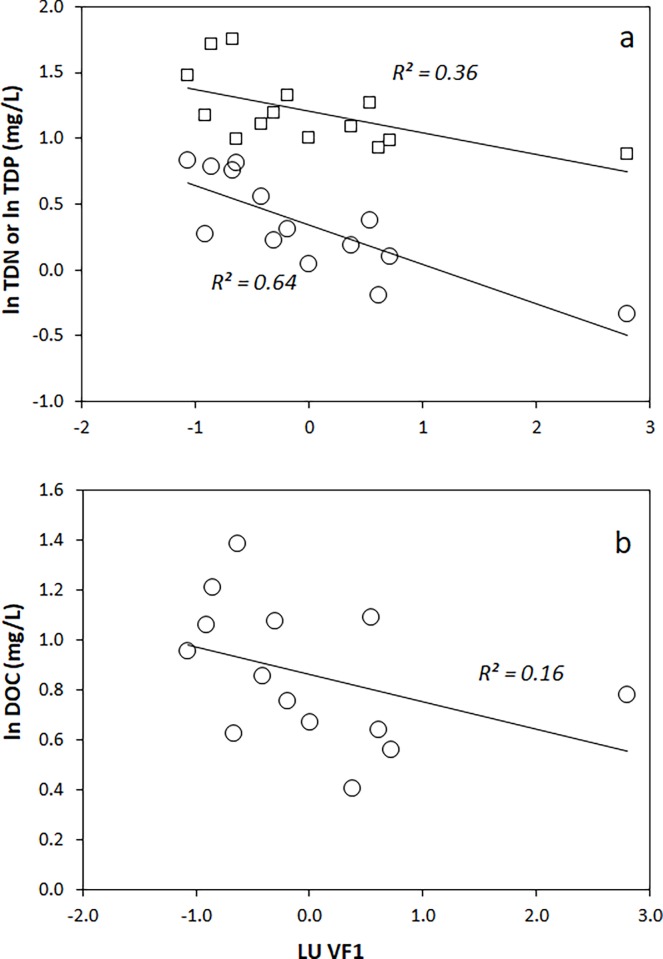

Based on the PCA groupings, we then performed univariate regressions comparing LULC VF1, and TDN, TDP, DOC as predictors of δ15N of nitrate, periphyton and all animal tissues. TDN concentration, which varied from 0.47 to 6.79 mg/L, was significantly correlated with LULC VF1 (R2 = 0.64, P < 0.01) (Fig 3A). TDP values, ranging from 7.6 to 56.9 mg/L, showed a positive correlation with riparian agriculture percentages as well (R2 = 0.36, P < 0.02) (Fig 3A). DOC ranged from 2.5 to 24.3 mg/L, and was not significantly correlated with LULC VF1 (R2 = 0.16, P < 0.05) (Fig 3B).

Fig 3.

TDN, TDP (a) and DOC (b) plotted against LULC VF1.

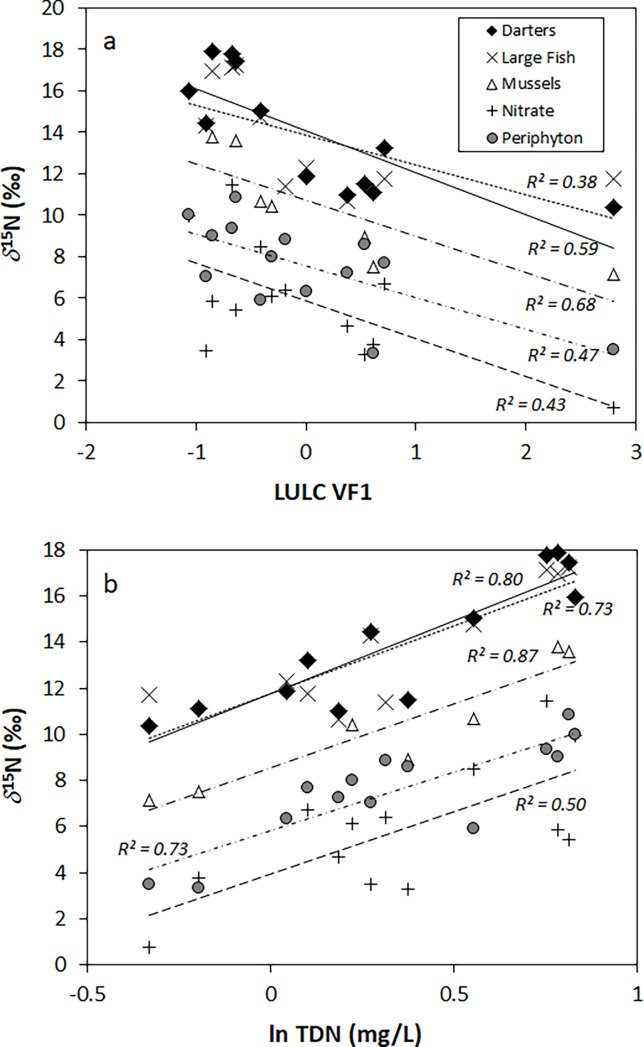

The δ15NNO3 data across all sites ranged from 0.7 to 11.4‰, and correlated strongly with LULC VF1 (R2 = 0.43, P < 0.05) (Fig 4A). Nitrate δ15N values increased relative to the expected range for chemical fertilizers and naturally-occurring nitrate derived from atmospheric deposition or soil nitrification processes, and are more characteristic of nitrate present in sewage or manure (Table 2). Periphyton δ15N values overlapped strongly with nitrate, and were strongly and positively correlated with LULC VF1 (R2 = 0.47, P < 0.05) (Fig 4A).

Fig 4.

δ 15N values of nitrate and animal tissues plotted against percent riparian monoculture (A) and TDN (B).

Table 2. Landscape and environmental data from all sites of study.

|

Location |

% Wooded | % Wetland | % Cultivation | % Developed | % Rural | % Miscellaneous | TDN (mg/L) | δ 15NNO3 (‰) | Temperature (°C) | Conductivity (mS/cm) | Dissolved Oxygen (mg/L) | TDP (mg/L) | [DOC] (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ausable River | 11.3 | 10.3 | 50.2 | 0.9 | 20.8 | 3.7 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 18.4 | 591.5 | 9.15 | 51.58 | 16.18 |

| Beaverton River | 7.5 | 38.9 | 11.9 | 0.7 | 12.1 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 25.2 | 510.5 | 6.22 | 14.98 | 11.58 |

| Cavanville Creek | 24.7 | 28.0 | 17.1 | 1.2 | 14.5 | 4.2 | 1.1 | 20.6 | 482 | 12.58 | 10.15 | 4.71 | |

| East Cross Creek | 20.2 | 31.5 | 18.5 | 0.5 | 7.6 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 6.4 | 18.7 | 383.3 | 8.33 | 21.18 | 5.71 |

| Fish Creek | 11.8 | 0.1 | 43.5 | 0.5 | 32.9 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 5.4 | 18.9 | 587 | 11.86 | 9.74 | 24.31 |

| Fleetwood Creek | 32.4 | 29.3 | 17.3 | 0.4 | 7.3 | 5.9 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 17 | 363.1 | 9.92 | 8.39 | 4.38 |

| Humber River | 25.6 | 26.0 | 8.7 | 2.5 | 13.6 | 11.2 | 1.3 | 6.7 | 17.7 | 555.5 | 10.94 | 9.68 | 3.65 |

| Indian River | 48.6 | 10.9 | 8.2 | 1.5 | 4.2 | 19.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 23.8 | 245.6 | 10.42 | 7.64 | 6.06 |

| Nonquon Creek | 28.8 | 24.5 | 15.0 | 0.6 | 15.5 | 7.7 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 16.9 | 380.6 | 9.24 | 18.72 | 12.29 |

| Nottawassaga | 27.6 | 27.4 | 17.2 | 0.0 | 17.0 | 5.4 | 1.5 | 4.7 | 15.1 | 393.4 | 11.12 | 12.3 | 2.54 |

| Sydenham River | 14.6 | 6.3 | 39.4 | 2.2 | 27.2 | 4.3 | 5.7 | 11.4 | 17.2 | 618 | 8.96 | 56.86 | 4.24 |

| Teeswater | 17.4 | 25.3 | 20.8 | 0.6 | 21.5 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 8.5 | 18.8 | 554 | 10.8 | 12.88 | 7.22 |

| Thames River | 4.0 | 34.8 | 29.9 | 1.1 | 18.0 | 4.2 | 6.8 | 9.9 | 16.7 | 700.5 | 8.02 | 29.67 | 9.05 |

| Uxbridge Brook | 17.8 | 32.2 | 13.2 | 3.6 | 13.4 | 5.5 | 1.7 | 6.1 | 21.5 | 476.7 | 10.42 | 15.72 | 11.93 |

Tissues from all fish species had more positive 15N signatures as compared to nitrate (11 to 17.9‰) (Fig 4A, Table 2), as further indicated by their larger y-intercept values when linear regressions were performed against both LULC VF1 and TDN. Both darters (R2 = 0.68, P < 0.01) and large fish (R2 = 0.38, P < 0.05) showed δ15N tissue values that correlated strongly with LULC VF1 (Fig 4A). Mussel tissues exhibited a range of δ15N values that mostly overlapped with those of nitrate (6.3 to 13.6‰) (Table 3), and these also displayed a significant positive correlation with LULC VF1 (R2 = 0.68, P < 0.01) (Fig 4A).

Table 3. Averaged animal tissue and periphyton stable isotope data from all sites of study.

| Location | δ 15N in Mussel Tissues (‰) | δ 15N in Darter Tissues (‰) | δ 15N in Trout/Bass Tissues (‰) | δ 13C in Darter Tissues (‰) | δ 13C in Trout/Bass Tissues (‰) | δ 13C in Mussel Tissues (‰) | δ 15N of Periphyton (‰) | δ 13C of Periphyton (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ausable River | 13.78 | 17.90 | 16.95 | -25.38 | -26.67 | -30.92 | 9.0 | -19.31 |

| Beaverton River | 14.43 | 14.31 | -28.86 | -27.83 | 7.0 | -20.83 | ||

| Cavanville Creek | 11.89 | 12.32 | -27.84 | -28.20 | 6.3 | -18.42 | ||

| East Cross Creek | 11.38 | -24.79 | 8.9 | -18.88 | ||||

| Fish Creek | 13.58 | 17.45 | 17.23 | -26.36 | -26.43 | -31.38 | 10.9 | -19.41 |

| Fleetwood Creek | 7.50 | 11.10 | -29.00 | -28.72 | 3.3 | -15.27 | ||

| Humber River | 13.24 | 11.74 | -27.18 | -26.32 | 7.7 | -18.08 | ||

| Indian River | 7.15 | 10.36 | 11.73 | -27.62 | -26.19 | -28.13 | 3.5 | -22.26 |

| Nonquon Creek | 8.94 | 11.51 | -29.86 | -33.96 | 8.6 | -22.88 | ||

| Nottawassaga | 10.99 | 10.66 | -29.18 | -29.83 | 7.2 | -18.86 | ||

| Sydenham River | 17.77 | 17.13 | -28.10 | -26.79 | 9.3 | -22.49 | ||

| Teeswater | 10.67 | 15.06 | 14.75 | -27.56 | -28.05 | -30.82 | 5.9 | -19.02 |

| Thames River | 15.97 | -28.98 | 10.0 | -20.07 | ||||

| Uxbridge Brook | 10.43 | -32.38 | 8.0 | -24.89 |

The strong relationships between all animal δ15N tissues, δ15N of periphyton, δ15NNO3, and TDN derived from the second PCA was investigated with an additional series of univariate regressions. TDN correlated strongly and positively with the δ15N of darters (R2 = 0.80, P < 0.01), large fish (R2 = 0.73, P < 0.01), and mussel tissue (R2 = 0.89, P < 0.01). Correlations of TDN against the δ15N of nitrate, while statistically significant, were weaker than that of animal tissues (R2 = 0.50, P < 0.01) (Fig 4B). However, a positive correlation of the δ15N of periphyton and TDN was comparatively strong (R2 = 0.72, P < 0.01). Mussel δ15N values displayed a significant positive correlation with the δ15NNO3 data (R2 = 0.75, P < 0.01), as did tissue δ15N from darter tissue δ15N (R2 = 0.48, P < 0.05), and periphyton δ15N (R2 = 0.43, P < 0.01) (Fig 5A).

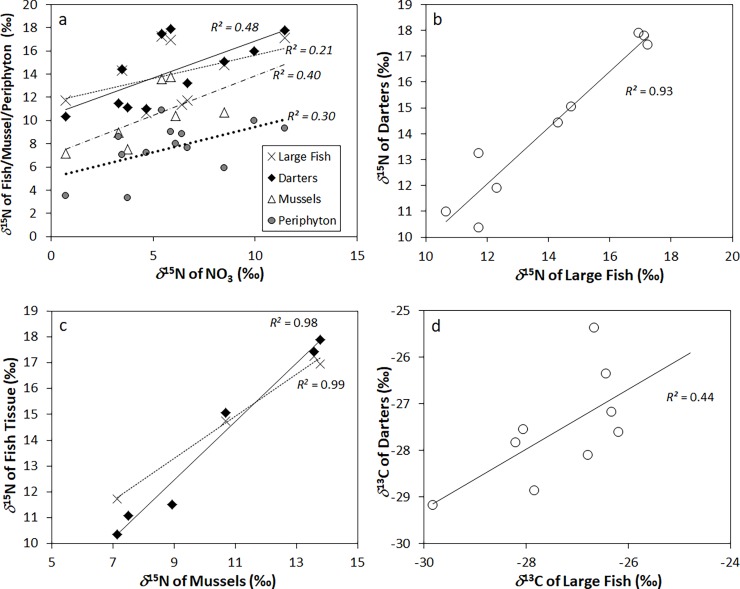

Fig 5.

δ15N of animal tissues plotted against δ15N of nitrate (a), δ15N of darters plotted against δ15N of trout and bass (b), δ15N of fish tissues plotted against δ15N of mussles (c), and δ13C of darters plotted against δ13C of trout and bass (d).

Correlations between animal tissue δ15N datasets were also strong. The δ15N values in darter tissues were significantly related with those in larger fish species (R2 = 0.93, P < 0.01) (Fig 5B). Positive correlations between all fish tissue δ15N signatures and those of mussel tissues were significant as well (R2 = 0.97 and P < 0.01 for trout and bass, and R2 = 0.48 and P < 0.01 for darters) (Fig 5C).

We also explored correlations between the animal tissue δ13C datasets. The δ13C of mussel tissues ranged from -28 to -34‰ and were comparatively 13C-depleted relative to all fish types, which exhibited tissue δ13C values ranging from -25 to -30‰ (Table 2). As with the δ15N data, the δ13C values of darter tissues did show a significant correlation with those of bass and trout species (R2 = 0.43, P < 0.01) (Fig 5D). Periphyton δ13C showed no significant correlations with those of fish and mussel tissues.

As well, none of the animal tissue or periphyton δ13C datasets was significantly related to land use, water temperature, conductivity, or dissolved oxygen. The stomach content analyses showed that bass and trout species were devoid of smaller fish types, and their diets were instead dominated by invertebrates such as crayfish, water beetles (Gyrinidae), midges (Chironomidae), and nematodes (Table 4).

Table 4. The presence or absence of prey items in the stomachs of selected fish species (4 specimens collected at each site).

| Site | Examined Fish Species | Crayfish | Gyrinidae | Chironomidae | Nematode | Unidentifiable (Liquid) | Empty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ausable River | Rock Bass | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fish Creek | Rock Bass | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sydenham River | Rock Bass | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Beaverton River | Rock Bass | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| East Cross Creek | Rock Bass | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Teeswater | Rock Bass | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cavanville Creek | Rock Bass | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nottawassaga | Brook Trout | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Humber River | Brown Trout | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Indian River | Rock Bass | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

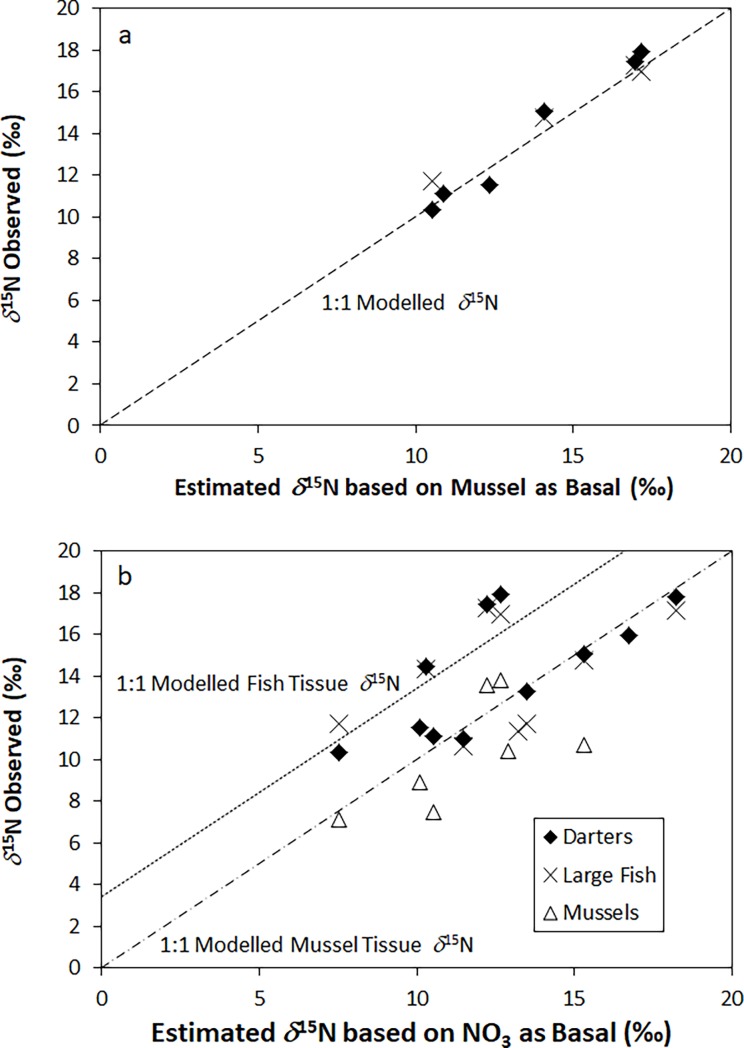

Using Eq (1), darters and larger bass and trout species had an average trophic 15N-fractionation of 3.90 ± 0.50‰ and 3.87 ± 0.60‰, respectively, which lies within the literature trophic fractionation range of 3 to 4‰. We also observed a close correspondence of collected animal tissue δ15N data and modelled values, assuming an average fractionation value of 3.4‰ [12] and using either δ15NNO3 or the δ15N of mussel tissue as trophic baselines (Fig 6A and 6B).

Fig 6.

A comparison of observed and modelled animal tissue δ15N values based on the equation of [17], using an assumed δ15N of 3.4‰ and using either the δ15N of nitrate (A) or mussel tissues (B) as baseline values.

Discussion

We found that agriculture strongly influences TDN and all δ15N datasets, and is most clearly reflected in the δ15N signatures of animal tissues, periphyton, and nitrate. The latter is more 15N-enriched than anticipated relative to natural sources, and instead resembles organic fertilizer and manure values which typically range from 7 to 20 ‰ [27]. Our findings indicate that the δ15N signatures of nitrates, periphyton, and animal tissues from all trophic levels are clear indicators of agricultural influence, since this cropland-derived nitrogen is also reflected in their δ15N.

A probable explanation for the comparatively 15N-enriched δ15NNO3 signatures and their strong positive correlations with agricultural land use is that the dissolved nitrogen at all locations is predominantly sourced from organic fertilizers and/or manure. This possibility is supported by the association of positive loadings by LULC VF1, δ13NNO3, TDP, TDN, conductivity, and δ15N of all animal tissues and periphyton in the PCA analyses. A similar trend was described by [27], who found that the δ15N signatures of nitrate in river waters collected in the Northeastern United States showed increasing 15N-enrichment with larger inputs of wastewater and manure. As well, studies by Pastor et al. [28] and Peipoch et al. [29] found that anthropogenic NO3 consistently exhibited the highest δ15NO3 signatures, with these also being expressed in the δ15N values of aquatic vegetation.

Processes such as bacterial denitrification and plant nitrate-uptake are also known to enrich residual nitrate in 15N [30, 31], and our previous work showing increases in bacterial activity with agriculture land use raises the possibility of such contributions to the observed 15N-enrichments [15, 18]. Normally, we would expect a negative correlation between δ15NNO3 and TDN if these denitrifying processes were prevalent, as the utilization of nitrate would reduce their concentrations as isotopic fractionation progressed [31, 32]. However, significant loadings of nitrogen derived from the dominance of denitrification processes could overcome this expected trend ([4, 12, 33]). Therefore, nitrate subject to denitrification could be another source of agriculturally-derived 15N-enriched nitrogen, perhaps in addition to fertilizer and manure application.

The positive relationships observed between the δ15N of mussel tissues and both δ15NNO3 and riparian monoculture percentages is further indicative of a significant agricultural influence on the δ15N signatures of baseline consumers. Comparable findings were obtained from studies by [10] and [11], which found that the δ15N of E. complanata was more enriched in agricultural and developed areas, as compared to forested sites. As well, a study by [4] found strong positive correlations between agricultural land-use percentages and the δ15N values of primary consumers, predatory invertebrates, and fish. Our study builds on this research by considering primary production in the form of periphyton, which was also shown to correlate with land use and δ15NNO3.

These findings, in addition to the strong correlations between mussel and fish tissue δ15N values, validate the utility of mussels for use as a trophic baseline. We assumed that the more enriched δ15N values in mussel tissues relative to nitrate, and in fish tissues relative to mussels, were primarily the result of trophic fractionation. This assumption is supported by the estimated 15N trophic fractionation values, which appear to broadly agree with those cited in earlier studies although some stronger variation occasionally exists.

However, the use of mussel tissue as a baseline appears to show a stronger fit between modelled and observed δ15N fish tissue signatures as compared to nitrate, which suggests a weaker correspondence between mussel tissue and nitrate. This is unexpected, as relationships between primary consumers and terrestrially-derived nitrate would likely be stronger than those between dissolved nitrate and secondary (or tertiary) consumers. The weaker correspondence could be a reflection of the diverse diet of mussels, which can include phytoplankton, zooplankton, bacteria, and general organic detritus derived from both aquatic and terrestrial sources [29]. All of these inputs vary in their δ15N signatures, which would lead to stronger variability in mussel tissue δ15N signatures and a weaker dependence of these on δ15NNO3.

In turn, the fish δ15N signatures are expected to correlate more strongly with those of mussel tissues, as mussel diets are generally representative of the bulk organic material in a given area [11]. Nevertheless, the correlation between mussel tissue δ15N and that of dissolved nitrate remains strong, which may be due to the influence of organic fertilizers on terrestrial organic matter [27]. If mussel diets are composed of appreciably large amounts of terrestrially-derived organic material, which in turn may incorporate a significant amount of fertilizer-sourced nitrogen, we would expect such a correlation between mussel tissue and dissolved nitrate.

Dietary variation may also account for the larger δ15N trophic fractionation values in all fish tissues as compared to the often-cited value of 3.4‰ [9]. Darters and larger species at some locations showed fractionation values as high as 4.38‰ and 4.58‰, respectively. Some of the trout specimens were found to contain whirligig beetles (gyrinidae), which are tertiary consumers and therefore are likely to be more 15N-enriched as compared to secondary consumers such as crayfish, midgefly larvae, or nematodes. The incorporation of gyrinidae into trout diets could shift tissue δ15N signatures towards more 15N-enriched values.

However, the δ15N values in darters are comparable to, and usually indistinguishable from, those observed in trout/bass. As the latter are expected to occupy a higher trophic level, one would normally expect the δ15N of darter tissues to be lower as compared to larger fish species. Previous studies have shown both greenside and johnny darters to incorporate similar prey, such as midgefly larvae and chironomids in their diet [34–37]. So rather than dietary variation, the convergence of δ15N darter and trout/bass values may instead suggest a genuine deviation from the expected 3.4‰ trophic fractionation value proposed by Post [9], although this difference is nonetheless comparatively minor.

Alternatively, the use of mussels as proxies for trophic consumer baseline values may not be entirely appropriate as a comparison to small and large fishes, with aquatic invertebrates (i.e., the preferred prey of all fish types) perhaps being more suitable for trophic 15N-fractionation estimates. Nonetheless, this discrepancy in 15N fractionation values highlights the possibility of variation in trophic isotope fractionation that is dependent on the studied region, and raises questions about the blind acceptance of a consistent trophic fractionation across all locations and environments.

In contrast to the δ15N data, the influence of land use on the δ13C signatures of animal tissues and periphyton is uncertain, as agricultural inputs would largely depend on the vegetation type comprising the DOC. Although corn, a C4 plant with a comparatively more 13C-enriched signature (~-14‰) as compared to C3 (~-26‰) vegetation [38], dominates much of the basin, a significant portion of riverine DOC is likely derived from fertilizer sourced from animal manure (as with nitrogen inputs). These would likely be comprised predominantly of C3 vegetation-derived soil carbonates and organic material that would be indistinguishable from natural sources, given the grass-based diet of cattle.

Our averaged δ13C values within fish tissues are generally consistent with median terrestrial C3 vegetation values. This is likely an expression of fish diet, as the observed stomach contents show that secondary consumers that feed largely on terrestrial detritus comprise the bulk of the fish diets [36]. On average, individual mussel tissue δ13C values are more 13C-depleted as compared to either darter-type species or trout and bass. However, this relative depletion is inconsistent, with average δ13C differences between mussel and fish tissues of 3.76 ± 3.02‰ and 0.14 ± 1.43‰ for darter-type species and bass/trout, respectively.

This comparative δ13C-depletion, and lack of correlation between fish and mussel δ13C tissue values, is likely due to a strong sensitivity of δ13C signatures to dietary differences. As mentioned previously, mussels are omnivorous and their food sources vary depending on their habitat, which likely results in correspondingly strong variations in the δ13C of food sources [37]. For example, mussels may filter-feed on zooplankton and phytoplankton from the open water column in streams, interstitially from the sediment, or pedal feed on bulk fractions of organic matter in sediment [21, 34].

These local habitat differences are more likely to affect mussel δ13C values rather than those of fish, which are consistently representative of organic material and biota within the water column. Therefore, in contrast to the 15N datasets, the mussel data may be less reliable as indicators of baseline trophic 13C values. A more accurate surrogate for a trophic δ13C baseline would likely be the invertebrates that most fish species directly feed on, such as crustaceans and insects.

The larger δ13C of periphyton relative to fish or mussel tissues also indicates that periphyton may not be an accurate indicator of bulk in-situ primary production δ13C values. This may be due to a stronger influence of soil-derived carbonates, given the similarity of periphyton δ13C values to soil-respired carbon (around -23.3‰; [38]). Aquatic algae rather than periphyton would likely provide δ13C values more representative of in-stream primary production, given that much terrestrially-derived detrital material may be incorporated into the collected periphyton samples.

Conclusions

We found agriculturally-derived nitrogen to be strongly related to the δ15N datasets and are comparable to expected organic fertilizer values. However, estimates of fish trophic position through use of δ15N data show occasionally larger deviations in trophic fractionation estimates from those in the literature. This indicates that caution should be exercised when assuming a uniform trophic isotope fractionation value across all locations of study, and that the use of a single, static value is an oversimplification. It may be more likely that 15N fractionation values vary more than previously supposed, and that this variation needs to be taken into account in future studies.

As well, our study shows that care must be taken when selecting an assumed trophic baseline upon which to estimate isotope fractionation values, which may vary widely depending on either the organism type or even its sampled location. In the case of this study, neither mussels nor periphyton may be accurate representatives of primary consumers and primary producers, respectively, and algae and small invertebrates are likely to be more appropriate for such studies. The wide range of 15N-signatures in dissolved nitrate also indicates the need to characterize source nitrogen with greater precision through further constraints on isotope data. This may require the δ15N analysis of other nitrogen species, such as ammonium, or the use of δ18O measurements.

The 13C data is less diagnostic of agricultural influences and show no consistent trophic isotopic fractionation, suggesting that carbon cycling dynamics are more complex as compared to those of nitrogen. Aquatic carbon cycles are composed of a complicated interplay of biological, geological, and even climatic variables, with any of the above possibly being a dominant factor depending on location. As such, ancillary measurements of both organic and inorganic carbon species should be included for additional clarity, in conjunction with more comprehensive sampling of additional biota. In particular, the δ13C values of aquatic invertebrates, rather than mussel tissue, may serve as a more appropriate trophic baseline in future studies due to their greater importance in fish diets.

Acknowledgments

We give thanks to Andrew Scott and Dr. Jean-Francois Koprivnjak for their advice and invaluable assistance with the laboratory analyses. This study was funded by Canada’s Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper, in Table 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by Canada’s Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC). The funding was received by Dr. Marguerite Xenopoulos and Kern Young Lee. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Foley JA, DeFries R, Asner GP, Barford C, Bonan G, Carpenter SR, et al. Global consequences of land use. science. 2005;309(5734):570–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1111772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith VH, Schindler DW. Eutrophication science: where do we go from here? Trends in ecology & evolution. 2009;24(4):201–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrington RR, Kennedy BP, Chamberlain CP, Blum JD, Folt CL. 15N enrichment in agricultural catchments: field patterns and applications to tracking Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Chemical Geology. 1998;147(3–4):281–94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson C, Cabana G. δ15N in riverine food webs: effects of N inputs from agricultural watersheds. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2005;62(2):333–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kling GW, Fry B, O'Brien WJ. Stable isotopes and planktonic trophic structure in arctic lakes. Ecology. 1992;73(2):561–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabana G, Rasmussen JB. Modelling food chain structure and contaminant bioaccumulation using stable nitrogen isotopes. Nature. 1994;372(6503):255. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanden M, Rasmussen JB. Primary consumer δ13C and δ15N and the trophic position of aquatic consumers. Ecology. 1999;80(4):1395–404. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Layman CA, Arrington DA, Montaña CG, Post DM. Can stable isotope ratios provide for communitytyumers. Ecology. 1999;80(4):1395–404.4.72(6503):255.nces. 200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Post DM. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology. 2002;83(3):703–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinney R, Lake J, Allen M, Ryba S. Spatial variability in mussels used to assess base level nitrogen isotope ratio in freshwater ecosystems. Hydrobiologia. 1999;412:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bucci JP, Levine JF, Showers WJ. Spatial variability of the stable isotope (δ 15N) composition in two freshwater bivalves (Corbicula fluminea and Elliptio complanata). Journal of Freshwater Ecology. 2011;26(1):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson C, Cabana G. Does δ15N in river food webs reflect the intensity and origin of N loads from the watershed? Science of the Total Environment. 2006;367(2–3):968–78. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hesslein R, Capel M, Fox D, Hallard K. Stable isotopes of sulfur, carbon, and nitrogen as indicators of trophic level and fish migration in the lower Mackenzie River basin, Canada. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 1991;48(11):2258–65. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson HF, Xenopoulos MA. Effects of agricultural land use on the composition of fluvial dissolved organic matter. Nature Geoscience. 2009;2(1):37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams CJ, Yamashita Y, Wilson HF, Jaffé R, Xenopoulos MA. Unraveling the role of land use and microbial activity in shaping dissolved organic matter characteristics in stream ecosystems. Limnology and Oceanography. 2010;55(3):1159–71. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams CJ, Scott AB, Wilson HF, Xenopoulos MA. Effects of land use on water column bacterial activity and enzyme stoichiometry in stream ecosystems. Aquatic sciences. 2012;74(3):483–94. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFeeters BJ, Xenopoulos MA, Spooner DE, Wagner ND, Frost PC. Intraspecific mass‐scaling of field metabolic rates of a freshwater crayfish varies with stream land cover. Ecosphere. 2011;2(2):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spooner DE, Frost PC, Hillebrand H, Arts MT, Puckrin O, Xenopoulos MA. Nutrient loading associated with agriculture land use dampens the importance of consumer‐mediated niche construction. Ecology Letters. 2013;16(9):1115–25. doi: 10.1111/ele.12146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulasekera K. Southern Ontario Region at a Glance. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). 2011.

- 20.(OMNR) OMoNR. Water Resources Information Project: Stream Networks Edition. Conservation Ontario, Peterborough ON. 2010.

- 21.Vaughn CC, Nichols SJ, Spooner DE. Community and foodweb ecology of freshwater mussels. Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 2008;27(2):409–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muholland P. Linx II Stream 15N Experimental Protocols. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge TN: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jardine T, McGeachy S, Paton C, Savoie M, Cunjak R. Stable isotopes in aquatic systems: sample preparation, analysis and interpretation. Can Manuscr Rep Fish Aquat Sci/Rapp Manuscr Can Sci Halieut Aquat. 2003;(2656):44. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis J. C., 1973. Statistics and Data Analysis in Geology. Wiley, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams CJ, Frost PC, Moralesles Data AM, Larson JH, Richardson WB, Chiandet AS, et al. Human activities cause distinct dissolved organic matter composition across freshwater ecosystems. Global change biology. 2016;22(2):613–26. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meglen RR. Examining large databases: a chemometric approach using principal component analysis. Marine Chemistry. 1992;39(1–3):217–37. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer B, Boyer EW, Goodale C, Jaworski NA, Van Breemen N, Howarth RW, et al. Sources of nitrate in rivers draining sixteen watersheds in the northeastern US: Isotopic constraints. Biogeochemistry. 2002;57(1):171–97. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pastor A, Riera JL, Peipoch M, Canñas L, Ribot M, Gacia Ea, et al. Temporal variability of nitrogen stable isotopes in primary uptake compartments in four streams differing in human impacts. Environmental science & technology. 2014;48(12):6612–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peipoch M, Gacia E, Blesa A, Ribot M, Riera JL, Martí E. Contrasts among macrophyte riparian species in their use of stream water nitrate and ammonium: insights from 15 N natural abundance. Aquatic sciences. 2014;76(2):203–15. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mariotti A, Mariotti F, Champigny M-L, Amarger N, Moyse A. Nitrogen isotope fractionation associated with nitrate reductase activity and uptake of NO3− by Pearl Millet. Plant Physiology. 1982;69(4):880–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granger J, Sigman DM, Lehmann MF, Tortell PD. Nitrogen and oxygen isotope fractionation during dissimilatory nitrate reduction by denitrifying bacteria. Limnology and Oceanography. 2008;53(6):2533–45. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kendall C. Tracing nitrogen sources and cycling in catchments. Isotope tracers in catchment hydrology: Elsevier; 1998. p. 519–76. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diebel MW, Zanden MJV. Nitrogen stable isotopes in streams: effects of agricultural sources and transformations. Ecological Applications. 2009;19(5):1127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strange RM. Diet Selectivity in the Johnny Darter, Etheostoma Nigrum, in Stinking Fork, Indiana. Journal of Freshwater Ecology. 1991;6(4):377–81. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bunt CM, Cooke SJ, McKinley RS. Creation and maintenance of habitat downstream from a weir for the greenside darter, Etheostoma blennioides–a rare fish in Canada. Environmental Biology of Fishes. 1998;51(3):297. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenfeld JS, Roff JC. Examination of the carbon base in southern Ontario streams using stable isotopes. Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 1992;11(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gustafson L, Showers W, Kwak T, Levine J, Stoskopf M. Temporal and spatial variability in stable isotope compositions of a freshwater mussel: implications for biomonitoring and ecological studies. Oecologia. 2007;152(1):140–50. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0633-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark ID, Fritz P. Environmental isotopes in hydrogeology: CRC press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper, in Table 1, 2, 3 and 4.