Abstract

Background and aims

The recent growth of Internet use has led to an increase of potentially problematic behaviors that can be engaged online, such as online gambling or Internet gaming. The aim of this study is to better conceptualize Internet gaming disorder (IGD) by comparing it with gambling disorder (GD) patients who only gamble online (online GD).

Methods

A total of 288 adult patients (261 online GD and 27 IGD) completed self-reported questionnaires for exploring psychopathological symptoms, food addiction (FA), and personality traits.

Results

Both clinical groups presented higher psychopathological scores and less functional personality traits when compared with a normative Spanish population. However, when comparing IGD to online GD, some singularities emerged. First, patients with IGD were younger, more likely single and unemployed, and they also presented lower age of disorder onset. In addition, they displayed lower somatization and depressive scores together with lower prevalence of tobacco use but higher FA scores and higher mean body mass index. Finally, they presented lower novelty seeking and persistence traits.

Discussion

GD is fully recognized as a behavioral addiction, but IGD has been included in the Appendix of DSM-5 as a behavioral addiction that needs further study. Our findings suggest that IGD and online GD patients share some emotional distress and personality traits, but patients with IGD also display some differential characteristics, namely younger age, lower novelty seeking scores and higher BMI, and FA scores.

Conclusions

IGD presents some characteristics that are not extensive to online GD. These specificities have potential clinical implications and they need to be further studied.

Keywords: gambling disorder, online gambling, Internet gaming disorder, behavioral addiction

Introduction

In the past few decades, with the continuous growth of Internet use, there has also been an increase of online gamblers (Kim, Wohl, Salmon, Gupta, & Derevensky, 2015) and Internet gaming players (Van Rooij, Schoenmakers, Vermulst, Van Den Eijnden, & Van De Mheen, 2011), as well as the conditions associated with its excessive use, namely online gambling disorder (online GD) and Internet gaming disorder (IGD). GD is a behavioral addiction characterized by persistent and recurrent maladaptive patterns of gambling behavior, leading to impaired functioning (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Some patients with GD only gamble through online platforms; however, it is also common for online gamblers to engage in other offline gambling behaviors (Hing, Russell, & Browne, 2017).

While GD is fully recognized as a behavioral addiction, IGD requires further study before it can robustly be considered a mental condition and, more specifically, a non-substance addiction (APA, 2013). Still, it can currently be diagnosed with the nine criteria proposed by the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; cut-off point set at 5 or more), and it is characterized by a persistent and recurrent use of Internet-based games, leading to impaired functioning (Petry et al., 2014). IGD is known to be more frequent in males than in females (Desai, Krishnan-Sarin, Cavallo, & Potenza, 2010; Gentile, 2009; Mentzoni et al., 2011), but its prevalence is still inconclusive. With this regard, a previous meta-analysis that included 33 different studies conducted in both adult and child population reported a high variability of prevalence rates, which would range from 3.1% to 8.9% (Ferguson, Coulson, & Barnett, 2011). One possible explanation is that the prevalence would be largely influenced by the measures used to assess the symptoms, the age of the participants, and cultural factors. For instance, studies that employed the DSM symptoms for pathological gambling to identify pathological gaming behavior reported higher overall prevalence (8.9%) than those that focused more specifically on evaluating the interference of the symptoms (3.1%). Similarly, a recent study conducted in Singapore with a wide sample of 1,251 current Internet users ranging from 13 to 40 years of age reported a prevalence of IGD that went up to 17.7%. However, it has to be noted that this prevalence was abstracted from the completion of online surveys, which included a 9-item self-reported questionnaire to asses IGD. Although this questionnaire is based on the DSM-5 criteria and has the same cut-off point, completers were not diagnosed by a specialized mental health professional.

Notably, a growing number of studies describe shared characteristics between IGD and addictions, including salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse (Griffiths, 2005; Ko, 2014; Kuss, Griffiths, Karila, & Billieux, 2014). In addition, an association between high video gaming and higher substance use of nicotine, alcohol, and cannabis was found in adolescents (Van Rooij et al., 2014) but also in adults (Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2014). Similarly, there is evidence that gambling co-occurs with substance abuse in adults (Barnes, Welte, Tidwell, & Hoffman, 2015) as well as adolescents (Barnes, Welte, Hoffman, & Tidwell, 2011).

In this line, the presence of food addiction (FA) in patients with IGD stands out as another addictive behavior that needs further investigation. FA is a term employed to describe addictive-like compulsive overeating, which involves cravings and difficulties with abstention of hyperpalatable food (Vella & Pai, 2017) and its prevalence has been highly linked to disordered eating attitudes and high body mass index (BMI; Gearhardt, Corbin, & Brownell, 2016; Meule, Hermann, & Kübler, 2015). In particular, the prevalence of FA is higher in all eating disorders (ED) when compared with healthy controls, but it appears to be higher in bulimia nervosa than other ED (de Vries & Meule, 2016; Hilker et al., 2016; Gearhardt, Boswell, & White, 2014). Noteworthy, disordered eating attitudes and BMI are linked to Internet addiction (Alpaslan, Koçak, Avci, & Uzel Taş, 2015; Canan et al., 2014; Rodgers, Melioli, Laconi, Bui, & Chabrol, 2013; Tao, 2013) and are strongly associated with IGD (Alpaslan et al., 2015; Canan et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2013; Tao, 2013). However, to date, there are no studies that analyze the presence of FA in patients who suffer from IGD. The only one, to our knowledge, that analyzed FA in GD showed positive significant association with younger age and sex (female) (Jiménez-Murcia, Granero, et al., 2017).

With regard to psychopathological symptoms and personality traits, previous studies carried out in both adult and adolescence populations reported higher impulsivity (Aboujaoude, 2017), mood and anxiety symptoms (Mentzoni et al., 2011; Van Rooij et al., 2014), as well as attention problems in frequent Internet gaming players when compared with non-frequent Internet gaming players. Similar psychological characteristics have also been described in clinical samples; adult patients with GD present high psychological distress and specific personality traits, such as impulsivity (Norbury & Husain, 2015) and sensation seeking, as well as high reward and punishment sensitivity (Hodgins & Holub, 2015; Jiménez-Murcia, Fernández-Aranda, et al., 2017; Lorains, Cowlishaw, & Thomas, 2011; Mestre-Bach et al., 2016).

Furthermore, there are three prior comparative studies exploring similarities and differences between IGD and GD with regard to different personality traits and neuropsychological factors. In particular, one of the studies investigated the Big Five personality traits in IGD and GD (Müller, Beutel, Egloff, & Wölfling, 2014) and their results show that patients with IGD display lower extraversion, lower conscientiousness, and higher openness when compared with the patients with GD. The second IGD and GD comparative study explored impulsivity and compulsivity dimensions; according to the results, patients with IGD present higher impulsivity and compulsivity in comparison with the patients with GD (Choi et al., 2014). Similar outcomes regarding impulsivity were elucidated in a third comparative study where IGD patients were more impulsive than GD patients. In this same study, neuropsychological differences were also examined concluding that both IGD and GD groups presented deficiencies in working memory and executive dysfunction in comparison with the control group (Zhou, Zhou, & Zhu, 2016). Given the scarce number of comparative studies exploring differences between GD and IGD, there is a need to replicate results before they can be conclusive. In addition, the three studies conducted to date do not consider that gambling preferences could also be playing a role in the differences observed between these two conditions. To date, no studies have explored differences between IGD and patients with GD who only gamble online.

The purpose of this study is to better conceptualize IGD by comparing it with a subgroup of a well-established behavioral addiction that gambles through online platforms (i.e., online GD). Behavioral addictions can overlap and in clinical practice, comorbidities are observed, but to explore IGD in itself, it is important to explore patients with IGD who do not present GD. By comparing online GD and IGD, our findings could help make evident for behavioral addiction clinicians the key characteristics that distinguish one group from another. To do so, we specifically explore: (a) psychopathological symptoms and personality traits; (b) weight and FA scores; and (c) disorder duration, severity, and substance use. Based on previous literature, it is hypothesized that IGD patients will present similar psychopathological symptoms as well as impulsive personality traits when compared with the online GD group. Based on clinical observation, it is also hypothesized that IGD patients will present differences in disorder duration and severity as well as substance use and eating behaviors/BMI when compared with the online GD group.

Methods

Sample

The final sample consisted of 288 patients of whom 261 exclusively presented online GD and 21 exclusively presented IGD, according to the DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2013). All participants were consequently referred through general practitioners or through another health care professional for problematic gambling or Internet gaming to the Bellvitge University Hospital Gambling Disorder Unit within the Department of Psychiatry. This public hospital is certified as a tertiary care center for the treatment of addictive behaviors and oversees the treatment of very complex cases. Experienced psychologists conducted two face-to-face clinical interviews before a diagnosis was given. Only patients who sought treatment for online GD or IGD as their primary health concern were admitted to this study and all participants were above 18 years old as our Gambling Disorder Unit is specialized in adults. Sociodemographic and additional clinical information was obtained, and patients individually completed all the questionnaires required for this study (requiring approximately 2 hr) before initiating outpatient treatment.

Exclusion criteria were: (a) history of chronic organic mental illness or neurological condition, such as psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, or Parkinson’s disease; (b) brain trauma, learning disability, or intellectual disabilities.

Instruments

Semi-structured face-to-face clinical interview

IGD patients were diagnosed according to the proposed “DSM-5 criteria,” which consist of nine different criteria and the presence of the disorder is set at a cut-off point of 5 or more criteria (APA, 2013; Petry et al., 2014). It should be noted that IGD has been included in the DSM-5 as a condition that requires further investigation to be considered as a behavioral addiction and that its diagnostic criteria are still not definitive. Patients presenting online GD were assessed with the DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2013). However, patients who were assessed before the release of the DSM-5 were diagnosed with pathological gambling, if they met DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). These patients were then reassessed and remodified post hoc and only patients who met DSM-5 criteria for GD and specifically online GD were included in our analysis.

Demographic and social variables related to gambling were measured. All participants also reported their weight and height, so that we could determine their BMI.

Self-reported measures

For the purpose of this study, all participants fulfilled self-reported questionnaires for exploring psychopathological symptoms, FA, and personality traits.

The “Yale Food Addiction Scale” (YFAS-S; Gearhardt, Corbin, & Brownell, 2009; adapated to Spanish population by Granero et al., 2014) is a 25-item self-report questionnaire to measure addictive food behaviors. It consists of seven scales, which refer to the criteria for substance dependence: (a) tolerance, (b) withdrawal, (c) substance taken in larger amount/period of time than intended, (d) persistent desire/unsuccessful efforts to cut down, (e) great deal of time spent to obtain substance, (f) important activities given up to obtain substance, and (g) use continued despite psychological/physical problems. The Cronbach’s α value for this study was .906.

The “Symptom Checklist-90-R” (Derogatis, 1994; adapted to Spanish population by González de Rivera, De las Cuevas, Rodríguez, & Rodríguez, 2002) is a 90-item questionnaire to measure psychological and psychiatric symptoms through nine dimensions: somatization, obsession–compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Cronbach’s α in our sample was in the good to excellent range (.81–.98; Table 2 includes α value for each scale).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical variables between online gambling disorder and Internet gaming disorder

| Online GD (n = 261) | IGD (n = 27) | ANOVA-adjusted age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | MD | p | | d | | |

| Severity evolution | ||||||||

| Diagnostic criteria | .854 | 6.89 | 2.14 | 5.53 | 1.88 | 1.37 | .002a | 0.68b |

| Age of onset (years) | 27.29 | 10.10 | 19.17 | 8.52 | 8.11 | <.001a | 0.87b | |

| Duration (years) | 4.61 | 4.97 | 3.84 | 2.52 | 0.76 | .431 | 0.19 | |

| Weight and food addiction | ||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2; present) | 25.73 | 3.72 | 28.22 | 5.23 | −1.49 | .044a | 0.55b | |

| YFAS: total raw score | .906 | 0.78 | 1.45 | 1.41 | 1.53 | −0.63 | .038a | 0.51b |

| Psychopathology: SCL-90-R | ||||||||

| Somatization | .916 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0.27 | .049a | 0.52b |

| Obsessive–compulsive | .878 | 1.15 | 0.82 | 1.16 | 0.72 | 0.00 | .978 | 0.01 |

| Interpersonal sensitiveness | .896 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 1.24 | 1.09 | −0.19 | .310 | 0.19 |

| Depression | .921 | 1.57 | 0.96 | 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.45 | .023a | 0.53b |

| Anxiety | .903 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.14 | .432 | 0.16 |

| Hostility | .876 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 1.11 | 0.82 | −0.06 | .761 | 0.07 |

| Phobic anxiety | .819 | 0.45 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.63 | −0.01 | .964 | 0.01 |

| Paranoid | .806 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 1.16 | 0.92 | −0.22 | .218 | 0.25 |

| Psychoticism | .867 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.10 | .531 | 0.13 |

| GSI score | .981 | 1.08 | 0.74 | 0.97 | 0.62 | 0.11 | .467 | 0.16 |

| PST score | .981 | 46.61 | 21.77 | 43.30 | 17.92 | 3.31 | .459 | 0.17 |

| PSDI score | .981 | 1.92 | 0.58 | 1.80 | 0.52 | 0.12 | .311 | 0.22 |

| Personality: TCI-R | ||||||||

| Novelty seeking | .753 | 110.39 | 14.69 | 102.42 | 16.53 | 7.97 | .011a | 0.52b |

| Harm avoidance | .816 | 100.41 | 16.78 | 104.39 | 10.90 | −3.98 | .252 | 0.28 |

| Reward dependence | .798 | 97.43 | 14.99 | 94.12 | 14.51 | 3.30 | .300 | 0.22 |

| Persistence | .895 | 107.66 | 20.73 | 92.97 | 18.03 | 14.69 | .001a | 0.76b |

| Self-directedness | .878 | 127.03 | 21.90 | 129.83 | 22.88 | −2.80 | .551 | 0.12 |

| Cooperativeness | .845 | 128.81 | 17.48 | 127.72 | 15.58 | 1.09 | .767 | 0.07 |

| Self-transcendence | .861 | 61.61 | 15.25 | 65.09 | 19.24 | −3.48 | .284 | 0.20 |

| Logistic adjusted by age | ||||||||

| Substances | n | % | n | % | OR | p | | d | | |

| Tobacco | 133 | 51.0 | 6 | 22.2 | 4.16 | .004a | 0.63b | |

| Alcohol | 18 | 6.9 | 0 | 0.0 | – | – | – | |

| Other drugs | 24 | 9.2 | 1 | 3.7 | 3.93 | .199 | 0.22 | |

Note. p value includes Bonferroni–Finner’s correction for multiple comparisons. GD: gambling disorder; IGD: Internet gaming disorder; SD: standard deviation; MD: mean difference; OR: odds ratio; α: Cronbach’s α in the sample; ANOVA: analysis of variance; BMI: body mass index; YFAS: Yale Food Addiction Scale; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist-90-R; TCI-R: Temperament and Character Inventory – Revised; GSI: Global Severity Index; PST: Positive Symptom Total; PSDI: Positive Symptom Distress Index.

Indicates significant result (.05 level).

Indicates moderate (| d | > 0.50) to high range (| d | > 0.80).

The “Temperament and Character Inventory – Revised” (Cloninger & Przybeck, 1994; adapted to Spanish population by Gutiérrez-Zotes et al., 2004) is a 240-item questionnaire to assess four dimensions of temperament (harm avoidance, novelty seeking, reward dependence, and persistence) and three character dimensions (self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence). In this study, the scales showed an adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α of .75–.90; Table 2 includes α value for each scale).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with Stata 15 for Windows. χ2 tests that compared categorical sociodemographic variables between groups and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was implemented for quantitative sociodemographic measures. Clinical variable comparison between the studied clinical groups (online GD and IGD) was based on ANOVA and adjusted by the participants’ chronological age (in the case of binary clinical variables, logistic regressions were employed adjusted by the same covariate). Due to multiple statistical comparisons, type-I error was controlled with the Finner’s (1993) procedure, which is a method included in the familywise error rate stepwise and is considered a more powerful test than the classical Bonferroni correction. The comparison effect size was estimated through Cohen’s d coefficient (moderate effect size was considered for | d | > 0.50 and high for | d | > 0.80).

Ethics

In accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 1983, the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari Bellvitge involved in the project approved the study. All subjects were informed about the study and provided informed consent prior to participation.

Results

Table 1 includes comparisons between the sociodemographic variables of the two studied samples. The two clinical groups differed in all the explored variables, except for the sex distribution. Online GD group presented a higher mean age and a higher number of patients with completed secondary or tertiary education, married, and/or employed. The IGD group had a higher percentage of immigrants, single participants, and lower education.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

| Online GD (n = 261) | IGD (n = 27) | Statistic (df) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Mean SD | 35.98 | 12.24 | 25.70 | 12.86 | F(1, 286) = 17.08 | <.001a |

| Gender (n, %) | ||||||

| Females | 12 | 4.6 | 3 | 11.1 | χ2(1) = 2.10 | .147 |

| Males | 249 | 95.4 | 24 | 88.9 | ||

| Origin (n, %) | ||||||

| Spain | 246 | 94.3 | 21 | 77.8 | χ2(1) = 9.83 | .002a |

| Immigrant | 15 | 5.7 | 6 | 22.2 | ||

| Education (n, %) | ||||||

| Primary | 98 | 37.5 | 19 | 70.4 | χ2(2) = 11.33 | .008a |

| Secondary | 124 | 47.5 | 5 | 18.5 | ||

| University | 39 | 14.9 | 3 | 11.1 | ||

| Civil status | ||||||

| Single | 133 | 51.0 | 23 | 85.2 | χ2(2) = 11.86 | .003a |

| Married – in couple | 104 | 39.8 | 4 | 14.8 | ||

| Divorced – separated | 24 | 9.2 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Employment (n, %) | ||||||

| Unemployed | 104 | 39.8 | 24 | 88.9 | χ2(1) = 23.83 | <.003a |

| Employed | 157 | 60.2 | 3 | 11.1 | ||

Note. GD: gambling disorder; IGD: Internet gaming disorder; SD: standard deviation.

Indicates the significant result (.05 level).

Table 2 includes the clinical profiles comparison of online GD and IGD (adjusted by age as a covariate).

Online GD displayed higher mean age of disorder onset and higher disorder severity (according to the number of DSM-5 criteria met) when compared with IGD. It also presented higher somatization and depression symptoms and higher scores in specific personality traits, namely novelty seeking and persistence. Still, IGD reported higher BMI and FA scores (when reported by YFAS). Regarding the use–abuse of substances (last rows of Table 2), binary logistic regressions adjusted by age did not report differences between groups in the consumption of alcohol or other drugs, but online GD showed a higher prevalence of tobacco use.

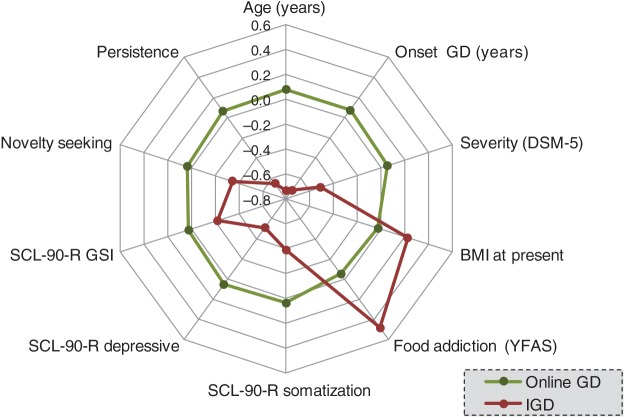

Figure 1 includes the radar chart with the variables that reached significant statistical differences in the comparison analyses. Due the different metric scales for the quantitative variables, z-standardized scores have been plotted to facilitate their interpretation.

Figure 1.

Radar-chart (z-standardized scores are plotted). Note. GD: gambling disorder; IGD: Internet gaming disorder

Discussion

This study compared a group of patients with IGD with an online GD group. IGD has been included in the Appendix of DSM-5 as a behavioral addiction that needs further study. Thus, research exploring different personality and psychopathological features among these patients is highly important. It was our aim to improve the conceptualization of IGD and provide behavioral addiction clinicians with a clearer picture of the features that distinguish these two groups from each other (i.e., IGD and online GD).

In our sample, IGD patients are younger (with also a younger age of disorder onset), more likely to be single, and have a higher rate of unemployment when compared with the online GD group. Our results are in line with previous studies reporting that IGD is more prevalent among adolescents and young adults (12–20 years of age; Festl, Scharkow, & Quandt, 2013). This could be due to the nature of Internet games in itself, which may be more appealing to adolescents and young adults. However, both groups (IGD and online GD) are rather young, if compared with the mean age described in land-based GD (Gainsbury, Russell, Blaszczynski, & Hing, 2015; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2011; Mestre-Bach et al., 2016); probably because they are part of a generation that is used to accessing the Internet on a daily basis. Conversely, given that we are conducting a cross-sectional study, we do not know if the unemployment rates are a consequence of IGD, a predisposing factor, or both, or maybe also related to other variables (e.g., young age).

Regarding psychopathology and personality traits, both online GD and IGD groups presented higher psychopathological scores and less functional personality traits when compared with a normative Spanish population (González de Rivera et al., 2002; Gutiérrez-Zotes et al., 2004). Specifically, both clinical groups have higher emotional distress together with higher harm avoidance and reward dependence traits than the normative group. These characteristics are also observed in other addiction-related behaviors (Ismael & Baltieri, 2014; Michalowski & Erblich, 2014; Zaaijer et al., 2014).

When comparing the online GD and the IGD groups, the latter presented lower somatization and depressive scores with lower sensation seeking and persistence traits. GD patients usually present high distress and psychopathology together with high scores of novelty seeking and impulsivity (Álvarez-Moya et al., 2010; Savvidou et al., 2017). This seems to be extended to our online GD sample but only partially extended to the IGD group, which presented a different personality profile with less impulsivity. It is important to note that no previous studies have been conducted so far comparing online GD and IGD; however, the three previous studies exploring differences between GD and IGD reported that patients with IGD display lower extraversions and lower conscientiousness as well as higher openness (Müller et al., 2014) and higher impulsivity and compulsivity (Choi et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2016) when compared with patients with GD. The differences found between our comparative study and these three studies seem to show some notable specificities linked to the patients who only gamble online when compared with IGD. Specifically, results show that differences in personality and psychopathology between IGD and GD could be reduced or even change when comparing patients who only gamble online.

In addition, IGD patients have lower tobacco consumption as well as higher BMI and FA scores compared with the online GD group. Comorbidities in addictive behaviors and substance-related addictions have been highly documented but not much explored in IGD. With regard to FA, it is a construct that has generally been explored with ED (Gearhardt et al., 2016) and its prevalence is very high within this clinical population. However, it is important to note that although no previous study have explored FA in IGD before, higher BMI and disordered eating have been strongly linked to both IGD (Alpaslan et al., 2015; Canan et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2013; Tao, 2013) and Internet-related addictive behaviors (Alpaslan et al., 2015; Canan et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2013). Thus the results of this study reporting higher FA in IGD raise the need to further explore FA and high BMI in patients with IGD as it might be an important treatment target for this population.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that explores psychopathology, personality, and addictive-related behaviors (namely, tobacco consumption and FA) in a group of IGD compared with an online GD group. The results are promising as they depict IGD similarities with behavioral addictions, such as high emotional distress (psychopathology symptoms), high reward dependence, and harm avoidance. They also emphasize specific IGD characteristics, namely younger years of age, lower novelty-seeking scores, as well as higher BMI and FA scores.

However, this research has some limitations that need to be considered. First of all, the cross-sectional design of this study cannot imply causality. In addition, the constrained number of patients with IGD may have an effect on the conducted statistical analyses, which can arguably be underpowered. However, it should be considered that the prevalence of IGD observed in clinical practice is still low compared with the online GD one (in this study, all patients referred for treatment between 2006 and 2017 were included) and that extra caution has been given for controlling sample size biases during the analyses. Still, our results should be contrasted with future research in IGD. In addition, both clinical groups are constituted of consecutive patients referred for treatment and have more males than females as well as different sample sizes. This is representative of the studied sample as previous studies describe higher prevalence of these disorders among males (Desai et al., 2010; Gentile, 2009; Mentzoni et al., 2011). Still, results have to be taken with caution before being generalized for both males and females. Finally, by exploring an exclusive sample of IGD and another of online GD, we aimed at better conceptualizing these conditions, but future studies should also explore the overlaps between them.

Conclusions

This study provides better understanding of the IGD in adulthood and compares it with an online GD group. Our findings suggest that IGD and online GD patients share some emotional distress and personality traits. However, compared with online GD, IGD patients present a younger age of onset and less novelty-seeking traits as well as less somatization and depression scores together with higher FA scores and BMI. These results indicate a specific psychological profile in IGD patients and also some shared characteristics with another behavioral addiction, namely GD patients with online gambling behaviors. Eventually, these findings can help improving current treatments for these patients.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Naif Mohammed for assistance with the IGD questionnaire data correction.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: This manuscript and research were supported by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) (FIS PI14/00290) and co-funded by FEDER funds/European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), a way to build Europe. CIBER Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBERobn) is an initiative of ISCIII. This study is also supported by de Economía y Competitividad (PSI2015-68701-R). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. ML-M is supported by a predoctoral grant of the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (FPU15/02911). GM-B is supported by a predoctoral grant of AGAUR (2016FI_B 00568).

Authors’ contribution

SJ-M, JMM, NM-B, RG, and FF-A designed the study and were involved in developing the research aims. SJ-M, NM-B, ML-M, and FF-A aided in the literature search and the framing of “Introduction” and “Discussion” sections. RG conducted the statistical analysis and RG, NM-B, SJ-M, and FF-A conducted the interpretation of the results. SJ-M, MB, GM-B, ADP-G, NA, and MG-P contributed to the data collection. NM-B, FF-A, ML-M, RG, GM-B, MB, ADP-G, MG-P, NA, JMM, and SJ-M were involved in writing, proofreading, and approving the final manuscript. All authors aided in preparing the revised manuscript they have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aboujaoude E. (2017). The Internet’s effect on personality traits: An important casualty of the “Internet addiction” paradigm. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(1), 1–4. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpaslan A. H. Koçak U. Avci K., & Uzel Taş H. (2015). The association between Internet addiction and disordered eating attitudes among Turkish high school students. Eating and Weight Disorders, 20(4), 441–448. doi:10.1007/s40519-015-0197-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Moya E. M. Jiménez-Murcia S. Aymamí M. N. Gómez-Peña M. Granero R. Santamaría J. Menchón J. M., & Fernández-Aranda F. (2010). Subtyping study of a pathological gamblers sample. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(8), 498–506. doi:10.1177/070674371005500804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4377-2242-0.00016-X [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G. M. Welte J. W. Hoffman J. H., & Tidwell M.-C. O. (2011). The co-occurrence of gambling with substance use and conduct disorder among youth in the United States. The American Journal on Addictions, 20(2), 166–173. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00116.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G. M. Welte J. W. Tidwell M.-C. O., & Hoffman J. H. (2015). Gambling and substance use: Co-occurrence among adults in a recent general population study in the United States. International Gambling Studies, 15(1), 55–71. doi:10.1080/14459795.2014.990396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canan F. Yildirim O. Ustunel T. Y. Sinani G. Kaleli A. H. Gunes C., & Ataoglu A. (2014). The relationship between Internet addiction and body mass index in Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(1), 40–45. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.-W. Kim H. Kim G.-Y. Jeon Y. Park S. Lee J.-Y. Jung H. Y. Sohn B. K. Choi J. S., & Kim D.-J. (2014). Similarities and differences among Internet gaming disorder, gambling disorder and alcohol use disorder: A focus on impulsivity and compulsivity. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(4), 246–253. doi:10.1556/JBA.3.2014.4.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger C., & Przybeck T. R. (1994). The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert_Cloninger/publication/264329741_TCI-Guide_to_Its_Development_and_Use/links/53d8ec870cf2e38c6331c2ee.pdf

- Derogatis L. R. (1994). Symptom checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R): Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Desai R. A. Krishnan-Sarin S. Cavallo D., & Potenza M. N. (2010). Video-gaming among high school students: Health correlates, gender differences, and problematic gaming. Pediatrics, 126(6), e1414–e1424. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries S.-K., & Meule A. (2016). Food addiction and bulimia nervosa: New data based on the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0. European Eating Disorders Review, 24, 518–522. doi:10.1002/erv.2470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson C. J. Coulson M., & Barnett J. (2011). A meta-analysis of pathological gaming prevalence and comorbidity with mental health, academic and social problems. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(12), 1573–1578. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festl R. Scharkow M., & Quandt T. (2013). Problematic computer game use among adolescents, younger and older adults. Addiction, 108(3), 592–599. doi:10.1111/add.12016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finner H. (1993). On a Monotonicity Problem in Step-Down Multiple Test Procedures. Source Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88(423), 920–923. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2290782 [Google Scholar]

- Gainsbury S. M. Russell A. Blaszczynski A., & Hing N. (2015). The interaction between gambling activities and modes of access: A comparison of Internet-only, land-based only, and mixed-mode gamblers. Addictive Behaviors, 41, 34–40. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt A. N. Boswell R. G., & White M. A. (2014). The association of “food addiction” with disordered eating and body mass index. Eating Behaviors, 15(3), 427–433. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt A. N. Corbin W. R., & Brownell K. D. (2009). Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite, 52(2), 430–436. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt A. N. Corbin W. R., & Brownell K. D. (2016). Development of the Yale Food Addiction Scale Version 2.0. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(1), 113–121. doi:10.1037/adb0000136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile D. (2009). Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18: A national study. Psychological Science, 20(5), 594–602. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02340.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González de Rivera J. L. de las Cuevas C. Rodríguez M., & Rodríguez F (2002). Cuestionario de 90 síntomas SCL-90-R de Derogatis, L. Española [Spanish symptom checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) of Derogatis, Spanish version]. Madrid, Spain: TEA. [Google Scholar]

- Granero R. Hilker I. Agüera Z. Jiménez-Murcia S. Sauchelli S. Islam M. A. Fagundo A. B. Sánchez I. Riesco N. Dieguez C. Soriano J. Salcedo-Sánchez C. Casanueva F. F. De la Torre R. Menchón J. M. Gearhardt A. N., & Fernández-Aranda F. (2014). Food addiction in a Spanish sample of eating disorders: DSM-5 diagnostic subtype differentiation and validation data. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(6), 389–396. doi:10.1002/erv.2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. (2005). A “components” model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. doi:10.1080/14659890500114359 [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Zotes J. A. Bayón C. Montserrat C. Valero J. Labad A. Cloninger C. R., & Fernández-Aranda F. (2004). Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised (TCI-R). Standardization and normative data in a general population sample. Actas Espanolas De Psiquiatria, 32(1), 8–15. Retrieved from http://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/43900600/Temperament_and_Character_Inventory_Revi20160319-6803-1nhjjpj.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1497274136&Signature=9ne5dsd0rHuSoMJkpxAC0DaLYGU%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3Bfilename%3DTemperament_and_Character_Inventory_Revi.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilker I. Sánchez I. Steward T. Jiménez-Murcia S. Granero R. Gearhardt A. N. Rodríguez-Muñoz R. C. Dieguez C. Crujeiras A. B. Tolosa-Sola I. Casanueva F. F. Menchón J. M., & Fernández-Aranda F. (2016). Food addiction in bulimia nervosa: Clinical correlates and association with response to a brief psychoeducational intervention. European Eating Disorders Review, 24, 482–488. doi:10.1002/erv.2473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing N. Russell A. M., & Browne M. (2017). Risk factors for gambling problems on online electronic gaming machines, race betting and sports betting. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 779. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D. C., & Holub A. (2015). Components of impulsivity in gambling disorder. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(6), 699–711. doi:10.1007/s11469-015-9572-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismael F., & Baltieri D. A. (2014). Role of personality traits in cocaine craving throughout an outpatient psychosocial treatment program. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 36(1), 24–31. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Murcia S. Fernández-Aranda F. Granero R. Chóliz M. La Verde M. Aguglia E. Signorelli M. S. Sá G. M. Aymamí N. Gómez-Peña M. del Pino-Gutiérrez A. Moragas L. Fagundo A. B. Sauchelli S. Fernández-Formoso J. A., & Menchón J. M. (2014). Video game addiction in gambling disorder: Clinical, psychopathological, and personality correlates. BioMed Research International, 2014, 315062. doi:10.1155/2014/315062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Murcia S. Fernández-Aranda F. Mestre-Bach G. Granero R. Tárrega S. Torrubia R. Aymamí N. Gómez-Peña M. Soriano-Mas C. Steward T. Moragas L. Baño M. del Pino-Gutiérrez A., & Menchón J. M. (2017). Exploring the relationship between reward and punishment sensitivity and gambling disorder in a clinical sample: A path modeling analysis. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(2), 579–597. doi:10.1007/s10899-016-9631-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Murcia S. Granero R. Wolz I. Baño M. Mestre-Bach G. Steward T. Agüera Z. Hinney A. Diéguez C. Casanueva F. F. Gearhardt A. N. Hakansson A. Menchón J. M., & Fernández-Aranda F. (2017). Food addiction in gambling disorder: Frequency and clinical outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 473. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Murcia S. Stinchfield R. Fernández-Arand F. Santamaría J. J. Penelo E. Granero R. Gómez-Peña M. Aymamí N. Moragas L. Soto A., & Menchón J. M. (2011). Are online pathological gamblers different fromnon-online pathological gamblers on demographics, gamblingproblem severity, psychopathology and personality characteristics?. International Gambling Studies, 11(3), 325–337. doi:10.1080/14459795.2011.628333 [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. S. Wohl M. J. A. Salmon M. M. Gupta R., & Derevensky J. (2015). Do social casino gamers migrate to online gambling? An assessment of migration rate and potential predictors. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1819–1831. doi:10.1007/s10899-014-9511-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko C.-H. (2014). Internet gaming disorder. Current Addiction Reports, 1(3), 177–185. doi:10.1007/s40429-014-0030-y [Google Scholar]

- Kuss D. J. Griffiths M. D. Karila L., & Billieux J. (2014). Internet addiction: A systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(25), 4026–4052. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24001297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorains F. K. Cowlishaw S., & Thomas S. A. (2011). Prevalence of comorbid disorders in problem and pathological gambling: Systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. Addiction, 106(3), 490–498. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03300.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentzoni R. A. Brunborg G. S. Molde H. Myrseth H. Skouverøe K. J. M. Hetland J., & Pallesen S. (2011). Problematic video game use: Estimated prevalence and associations with mental and physical health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(10), 591–596. doi:10.1089/cyber.2010.0260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestre-Bach G. Granero R. Steward T. Fernández-Aranda F. Baño M. Aymamí N. Gómez-Peña M. Agüera Z. Mallorquí-Bagué N. Moragas L. Del Pino-Gutiérrez A. Soriano-Mas C. Navas J. F. Perales J. C. Menchón J. M., & Jiménez-Murcia S. (2016). Reward and punishment sensitivity in women with gambling disorder or compulsive buying: Implications in treatment outcome. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 658–665. doi:10.1556/2006.5.2016.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meule A. Hermann T., & Kübler A. (2015). Food addiction in overweight and obese adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. European Eating Disorders Review, 23, 193–198. doi:10.1002/erv.2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalowski A., & Erblich J. (2014). Reward dependence moderates smoking-cue- and stress-induced cigarette cravings. Addictive Behaviors, 39(12), 1879–1883. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K. W. Beutel M. E. Egloff B., & Wölfling K. (2014). Investigating risk factors for Internet gaming disorder: A comparison of patients with addictive gaming, pathological gamblers and healthy controls regarding the big five personality traits. European Addiction Research, 20(3), 129–136. doi:10.1159/000355832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbury A., & Husain M. (2015). Sensation-seeking: Dopaminergic modulation and risk for psychopathology. Behavioural Brain Research, 288, 79–93. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2015.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N. M. Rehbein F. Gentile D. A. Lemmens J. S. Rumpf H. J. Mößle T. Bischof G. Tao R. Fung D. S. Borges G. Auriacombe M. González Ibáñez A. Tam P., & O’Brien C. P. (2014). An international consensus for assessing Internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction, 109(9), 1399–1406. doi:10.1111/add.12457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers R. F. Melioli T. Laconi S. Bui E., & Chabrol H. (2013). Internet addiction symptoms, disordered eating, and body image avoidance. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(1), 56–60. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savvidou L. G. Fagundo A. B. Fernández-Aranda F. Granero R. Claes L. Mallorquí-Baqué N. Verdejo-Garcíam A. Steiger H. Israel M. Moragas L. Del Pino-Gutiérrez A. Aymamí N. Gómez-Peña M. Agüera Z. Tolosa-Sola I. La Verde M. Aguglia E. Menchón J. M., & Jiménez-Murcia S. (2017). Is gambling disorder associated with impulsivity traits measured by the UPPS-P and is this association moderated by sex and age? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 72, 106–113. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Z. (2013). The relationship between Internet addiction and bulimia in a sample of Chinese college students: Depression as partial mediator between Internet addiction and bulimia. Eating and Weight Disorders, 18(3), 233–243. doi:10.1007/s40519-013-0025-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij A. J. Kuss D. J. Griffiths M. D. Shorter G. W. Schoenmakers M. T., & van de Mheen D. (2014). The (co-)occurrence of problematic video gaming, substance use, and psychosocial problems in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(3), 157–165. doi:10.1556/JBA.3.2014.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij A. J. Schoenmakers T. M. Vermulst A. A. Van Den Eijnden R. J. J. M., & Van De Mheen D. (2011). Online video game addiction: Identification of addicted adolescent gamers. Addiction, 106(1), 205–212. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella S.-L., & Pai N. (2017). What is in a name? Is food addiction a misnomer? Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 25, 123–126. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2016.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaaijer E. R. Bruijel J. Blanken P. Hendriks V. Koeter M. W. Kreek M. J. Booij J. Goudriaan A. E. van Ree J. M., & van den Brink W. (2014). Personality as a risk factor for illicit opioid use and a protective factor for illicit opioid dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 145, 101–105. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.09.783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. Zhou H., & Zhu H. (2016). Working memory, executive function and impulsivity in Internet-addictive disorders: A comparison with pathological gambling. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 28(2), 92–100. doi:10.1017/neu.2015.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]