Abstract

Background and aims

The smartphone is one of the most popular devices, with the average smartphone usage at 162 min/day and the average length of phone usage at 15.79 hr/week. Although significant concerns have been made about the health effects of smartphone addiction, the relationship between smartphone addiction and accidents has rarely been studied. We examined the association between smartphone addiction and accidents among South Korean university students.

Methods

A total of 608 college students completed an online survey that included their experience of accidents (total number; traffic accidents; falls/slips; bumps/collisions; being trapped in the subway, impalement, cuts, and exit wounds; and burns or electric shocks), their use of smartphone, the type of smartphone content they most frequently used, and other variables of interests. Smartphone addiction was estimated using Smartphone Addiction Proneness Scale, a standardized measure developed by the National Institution in Korea.

Results

Compared with normal users, participants who were addicted to smartphones were more likely to have experienced any accidents (OR = 1.90, 95% CI: 1.26–2.86), falling from height/slipping (OR = 2.08, 95% CI: 1.10–3.91), and bumps/collisions (OR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.16–2.87). The proportion of participants who used their smartphones mainly for entertainment was significantly high in both the accident (38.76%) and smartphone addiction (36.40%) groups.

Discussion and conclusions

We suggest that smartphone addiction was significantly associated with total accident, falling/slipping, and bumps/collisions. This finding highlighted the need for increased awareness of the risk of accidents with smartphone addiction.

Keywords: smartphone addiction, accident, falling, slipping, bumps, collisions

Introduction

The use of smartphones has been exponentially increasing worldwide, and they have become an integral part of our everyday lives (Kim et al., 2016; Monacis, de Palo, Griffiths, & Sinatra, 2017; Wu, Cheung, Ku, & Hung, 2013). In addition to the phone and text services, smartphones allow users to make real-time broadcasts, send/receive emails, utilize global positioning system (GPS) services, and play games (Rosen, Whaling, Carrier, Cheever, & Rokkum, 2013). Furthermore, smartphones include powerful technology that allows continuous interaction with online services, thus allowing users to consume a wide range of content, including that unrelated to their present time and location (Park & Lee, 2014).

Due to these attractive functions/applications and easy access, smartphone users have become dependent on such devices or develop the habit of excessively checking their phones without conscious self-control. Then, how does a smartphone user become a smartphone addictive user? In light of the principles of operant conditioning, smartphone users (triggered by internal or external cues) constantly gain “rewards” such as information acquisition, social interactions, and pleasure. Consequently, they are far more likely to use their smartphones with little conscious awareness (Lin & Huang, 2017). For example, commuters in bus stations generally experience dead time and, due to the constant stimuli provided by smartphones, the condition response is to immediately use such devices. Therefore, such “rewards” from smartphone use can lead to repeated or excessive use of these devices, which can ultimately cause smartphone addiction (Benowitz, 2008; Duke & Montag, 2017). Regarding frameworks on the smartphone addiction pathways, Billieux (2012) suggested four pathways: (a) impulsive pathway, indicating poor self-control and maladaptive emotions; (b) relationship maintenance pathway, indicating overuse for reassuring an affective relationship; (c) extraversion pathway, indicating the desire to communicate with others and build new relationships; and (d) cyber addiction pathway, indicating the excessive enjoyment of online activities (Billieux, 2012). Another model of smartphone addiction has shown that genetic and environmental effects can increase the risk of smartphone addiction by influencing dysfunctional conditions (Duke & Montag, 2017).

Problematic smartphone use is associated with elevated negative effect and lower positive effect. Moreover, subjects who are addicted to smartphones are more likely to have health problems, such as physical ailments (e.g., craniocervical posture, dry eyes, carpal tunnel syndrome, and headaches) and mental issues (e.g., fear, sadness, anger, psychopathological symptoms, depression, and anxiety), compared with normal smartphone users (Demirci, Akgönül, & Akpinar, 2015; Kee, Byun, Jung, & Choi, 2016; Kim, 2013; Kwon, Lee, et al., 2013; Montag, Sindermann, Becker, & Panksepp, 2016; Wegmann, Stodt, & Brand, 2015). Smartphone use at night or overuse of smartphone has been shown to affect sleep quantity and quality, depleting the following day’s productivity (Demirci et al., 2015; Lanaj, Johnson, & Barnes, 2014). The realm of family communication between parents and their children or of social participation also gets affected by the overuse of smartphones or mobile devices (Kuss & Griffiths, 2011; Radesky et al., 2014). Another emerging issue related to smartphone uses is the occurrence of accidents. In the USA, non-fatal pedestrian injury rates have increased with the steady rise in use of mobile phones (Byington & Schwebel, 2013). In Korea, recent data have shown that accidents associated with smartphone use among pedestrians have increased by 1.9 times over 4 years compared with the increase of only 1.1 times in the total number of accidents (Lim, Lee, Choi, & Joo, 2016). This may be explained by transportation safety issues (e.g., high road/traffic fatalities and injuries) among distracted pedestrians and drivers (Kong, Xiong, Zhu, Zheng, & Long, 2015; Nasar & Troyer, 2013). Many researchers have also expressed concerns regarding increased accident risks among those talking, texting, or listening to music on their phones while on the road (Brodsky & Slor, 2013; Nemme & White, 2010; Redelmeier & Tibshirani, 1997; Schwebel et al., 2012).

These accident risks particularly apply to excessive use of smartphones. Smartphone-addicted users can be highly preoccupied with their contents while performing other tasks (Lin et al., 2015). Dual- or multitasking (e.g., performing two or more tasks simultaneously), even among people on the move, often requires too much attention, thus resulting in reduced performance (Jansen, van Egmond, & de Ridder, 2016) and increased accidents both indoors as well as outdoors (Chaparro, Wood, & Carberry, 2005; Haigney & Westerman, 2001; Merchant, 2012; Strayer & Drew, 2004). However, although smartphone addiction can increase the risk of accidents, it has received limited attention from scholars.

Based on circumstantial evidence linking smartphone use to increased risk of accidents, this study hypothesized that, since it is difficult to switch one’s attention away from a smartphone in potentially dangerous situations, smartphone-addicted users have met with more number of accidents (including traffic accidents) than normal smartphone users. In addition, if the accident risks of smartphone users are attributable to dual- or multitasking, then there may be a difference in the content accessed over smartphones between those who experience accidents and those who do not.

This study aims to examine the association between smartphone addiction and the occurrence of accidents among Korean university students. For this purpose, it compared the frequencies and types of accidents as well as contents accessed over smartphones between a smartphone addictive group and a normal user group.

Materials and Methods

Study population

An online questionnaire-based survey was conducted by a professional research agency from August to September 2016. The platform for the survey was the Do-it Survey Solution (http://www.dooit.co.kr/), which was designed using the Hypertext Preprocessor/Linux web operating system and a database system based on MySQL product. The study included 608 Korean university students who owned smartphones and had agreed to participate. The online questionnaire was designed so that it could not be submitted unless every question was answered; therefore, there were no missing data, and all respondents were included in the analysis.

The participants responded to self-reported questionnaires that covered the following: their use of smartphones; sociodemographic characteristics including age, sex, monthly income (≤2,000,000, 2,000,000–5,000,000, or ≥5,000,000 KRW), housemate status (with family or with others but not family), and their major field of study (natural science, social science, or arts); and health behaviors, including smoking status (current, ex-, or never smoker) and current alcohol consumption status (yes or no).

Smartphone addiction

Smartphone addiction has not been included in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Thus, smartphone addiction is not an officially recognize diagnosis. In this study, smartphone addiction has been assessed using the Smartphone Addiction Proneness Scale (SAPS), which was developed by the National Information Society Agency of South Korea (Kwon, Lee, et al., 2013). Since the SAPS has high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of .880, it is suitable for screening subjects who are at risk of smartphone addiction (Kim, Lee, Lee, Nam, & Chung, 2014; Korean National Information Society Agency, 2011; Shin, Kim, & Jung, 2011).

The scale comprises four subcomponents: tolerance (four items; e.g., “Having tried to shorten smartphone use time but fails all the time,” Cronbach’s α = .828), withdrawal (four items; e.g., “Won’t be able to stand not having a smartphone,” Cronbach’s α = .797), virtual life orientation (two items; e.g., “Feeling empty when not using my smartphone,” Cronbach’s α = .691), and disturbance of adaptive functions (five items; e.g., “Having performance degradation in class or office due to smartphone use,” Cronbach’s α = .873) (Kim et al., 2014). These are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all,” 2 = “disagree,” 3 = “agree,” and 4 = “always”). Based on this scale, the participants were classified into three groups according to their risk of smartphone addiction: the high-risk group (total score, ≤45; disturbance of adaptive functions, ≤16; withdrawal score, ≤13; and tolerance score, ≤14); the potential-risk group (total score, 42–44; disturbance of adaptive functions, ≤14; withdrawal score, ≤12; and tolerance score, ≤13); and the normal user group (those not belonging to either of the other groups). For this study, we designated the high-risk and potential-risk groups as the “smartphone addiction group” and the remaining group as the “normal user group.”

The most used smartphone content

The participants were asked which type of smartphone content they used the most. The options included the following five group: (a) web-surfing (news searching and general web-surfing); (b) study/work (studying and searching for study or work); (c) entertainment (games, music, web-toons, gambling, movies, and TV); (d) social network services (SNSs) (e-mail, messenger, blogs, and SNSs, including Facebook); and (e) other (pornography, online-shopping, GPS, and banking).

Experiences of accidents

The participant’s experience of accidents was assessed from self-reports in which a multiple-choice question was administrated asking whether the respondent had experienced any of the following six types of accidents while using a smartphone: “a traffic accident;” “a fall from a height or a slip;” “a bump or collision;” “being trapped in the subway;” “impalement, cuts, and an exit wound;” or “burn or electric shock.” The total number of accidents indicated that the participant had experienced at least one of the above six types of accidents. The responses were coded as a dichotomous variable (“yes” or “no”).

Statistical analysis

Differences in the characteristics of the participants in the two smartphone user groups and their experience of accidents were evaluated using the χ2 test and Mann–Whitney U test. Point-biserial correlation analysis was performed to determine relationships of smartphone addiction with the total number of accidents and with the six types of accidents. To investigate the association between smartphone addiction and experience of accidents, we performed unadjusted and multivariate adjusted logistic regression analysis. The model was adjusted for potential covariates, including age, sex, major field of study, monthly income, residence, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. Finally, Figures 2 and 3 show the results of the χ2 tests of differences in smartphone content use for the two smartphone user groups and the two groups who had and had not experienced accidents. All analyses were performed using the SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and statistical significance was set at 0.05.

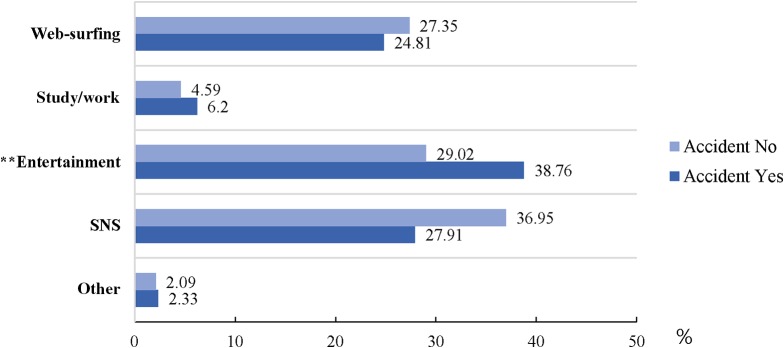

Figure 2.

Prevalence (%) of accidents by smartphone contents mainly used by college students (**p < .05)

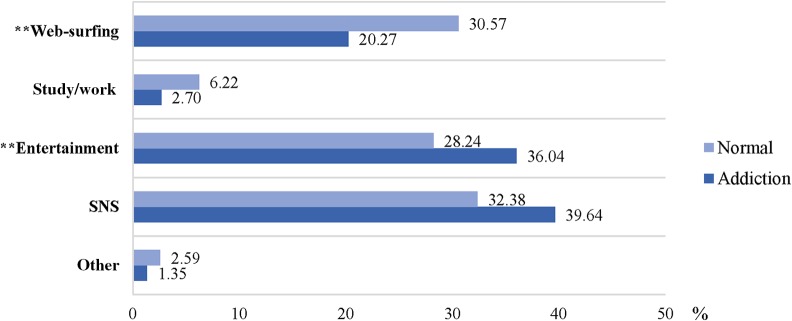

Figure 3.

Prevalence (%) of smartphone addiction against the mainly used contents of smartphone users (**p < .05)

Ethics

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Institutional Review board of Seoul National University Hospital. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population (N = 608) based on smartphone addiction. The mean (SD) ages of the smartphone-addicted group and the normal users group were significantly different (p = .010): 22.54 (2.05) years versus 23.01 (2.32) years. Overall, the female participants were more likely to be addicted to their smartphones (p = .002). In addition, the proportion of addicted students, including those with the lowest monthly income (43.41%), those living with their families (36.55%), those majoring in the arts (40.98%), those currently smoking (45.16%), and those currently drinking (37.57%), was higher than their counterparts. However, no significant differences were found in monthly income (p = .1836), residence (p = .9770), major field of study (p = .6916), smoking status (p = .3113), or alcohol consumption (p = .1428) between the two groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population by smartphone addiction

| Smartphone addiction (N = 222) | Normal (N = 386) | p value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N or mean | % or SD | N or mean | % or SD | ||

| Age | |||||

| Year | 22.54 | 2.05 | 23.01 | 2.32 | .0245 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 50 | 27.32 | 133 | 72.68 | .0020 |

| Female | 172 | 40.47 | 253 | 59.53 | |

| Monthly income (KRW) | |||||

| ≤2,000,000 | 56 | 43.41 | 73 | 56.59 | .1863 |

| 2,000,000–5,000,000 | 112 | 34.67 | 211 | 65.33 | |

| ≥5,000,000 | 54 | 34.62 | 102 | 65.38 | |

| Residence | |||||

| With family | 163 | 36.55 | 283 | 63.45 | .9770 |

| Others | 59 | 36.42 | 103 | 63.58 | |

| Major field of study | |||||

| Natural science | 90 | 35.16 | 166 | 64.84 | .6916 |

| Social science | 107 | 36.77 | 184 | 63.23 | |

| Arts | 25 | 40.98 | 36 | 59.02 | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Current | 28 | 45.16 | 34 | 54.84 | .3113 |

| Ex | 17 | 37.78 | 28 | 62.22 | |

| Never | 177 | 35.33 | 324 | 64.67 | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| Yes | 201 | 37.57 | 334 | 62.43 | .1428 |

| No | 21 | 28.77 | 52 | 71.23 | |

Note. SD: standard deviation.

p value was based on the Mann–Whitney U test for a continuous variable and the χ2 test for categorical variables.

The point-biserial correlation analysis showed significant correlations between smartphone addiction scores and total accidents (r = .17, p < .001), falling/slipping (r = .13, p = .001), and bumps/collisions (r = .15, p = .0003), but not for other types of accident (p > .05). There was no significant correlation between the total score of smartphone addiction and age of the participants (r = .07, p = .1080).

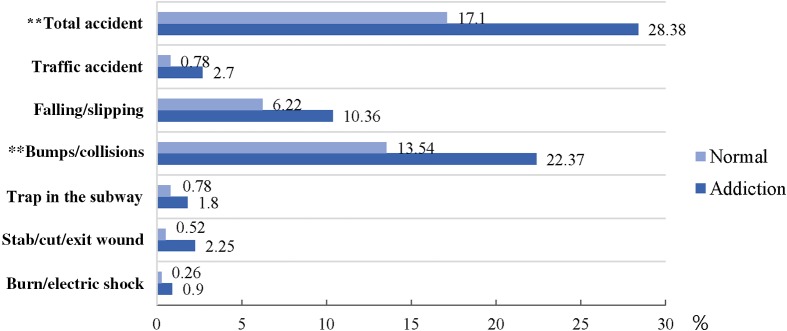

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of the experience of accidents in the two groups. A greater proportion of smartphone addiction group experienced an accident of some type (28.38%) as well as bumps and collisions (22.37%). However, no significant differences were observed in the number of accidents: falls from a height and a slip; being trapped in the subway; impalements, cuts, and exit wounds; and burn and electric shocks. Regarding the gender differences in accident experiences among smartphone-addicted students, the male participants were more likely to experience only traffic accidents (18.0% vs. 8.1%; p = .0440) than female participants.

Figure 1.

Prevalence (%) of the experience of accidents associated with smartphone addiction (**p < .05)

Table 2 shows the multiple logistic regression model’s estimates of the association between smartphone addiction and the experience of accidents, with odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) indicating the increased experience of accidents among addicted users compared with that among normal users. A significant association was observed between the total number of accidents experienced and smartphone addiction both before (OR = 1.92, 95% CI: 1.30–2.85) and after (OR = 1.90, 95% CI: 1.26–2.86) adjusting for age, sex, major field of study, monthly income, residence, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, although OR decreased following adjustment. Smartphone-addicted users were more likely to suffer bumps or collision (OR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.18–2.80; adjusted OR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.15–2.84). Furthermore, after adjusting for potential covariates, smartphone addiction was significantly associated with an increased experience of slips (OR = 1.92, 95% CI: 1.00–3.67).

Table 2.

Odds ratio (95% CI) for experience of accident by smartphone addiction

| Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | |

|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| Total accident | ||

| Smartphone addiction | 1.92 (1.30–2.85) | 1.90 (1.26–2.86) |

| Normal | Reference | Reference |

| Traffic accident | ||

| Smartphone addiction | 3.55 (0.88–14.32) | 3.76 (0.85–16.72) |

| Normal | Reference | Reference |

| Falling/slipping | ||

| Smartphone addiction | 1.74 (0.96–3.17) | 2.08 (1.10–3.91) |

| Normal | Reference | Reference |

| Bumps/collisions | ||

| Smartphone addiction | 1.84 (1.20–2.83) | 1.83 (1.16–2.87) |

| Normal | Reference | Reference |

| Trap in the subway | ||

| Smartphone addiction | 2.34 (0.52–10.56) | 2.85 (0.59–13.76) |

| Normal | Reference | Reference |

| Stab/cut/exit wound | ||

| Smartphone addiction | 4.42 (0.85–23.00) | 4.56 (0.83–25.03) |

| Normal | Reference | Reference |

| Burn/electric shock | ||

| Smartphone addiction | 3.51 (0.32–38.82) | 4.40 (0.27–72.83) |

| Normal | Reference | Reference |

Note. CI: confidence interval. Values are adjusted by age, sex, major field of study, monthly income, residence, smoking status, and alcohol consumption.

Figure 2 displays the prevalence of accidents according to the smartphone content type mainly used by the participants. A significantly higher proportion of participants who mostly used their smartphones for entertainment had experienced an accident (38.76%) than those who mostly used their smartphones for other content types. No significant difference was observed between the proportions of participants who mostly used their phones for web-surfing, study/work, or social networking, and had experienced an accident.

Figure 3 shows the prevalence of smartphone addiction according to the mainly used content types. A significantly lower proportion of smartphone-addicted users (20.27%) than normal users (30.57%) most frequently used their phones for web-surfing. Conversely, a significantly higher percentage of smartphone-addicted users (36.04%) than normal users (28.24%) used their phones most frequently for entertainment.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between smartphone addiction and the occurrence of accidents by examining the differences between smartphone-addicted users and normal users. Overall, participants who were addicted to smartphone were more likely to have experienced accidents. More specifically, smartphone addiction was associated with a higher likelihood of falling or slipping and of experiencing bumps or collisions, even after adjusting for any covariates. In addition, those who were addicted to smartphones or had experienced accidents were more likely to use entertainment-related content than normal users. The findings suggest that safety among university students may be jeopardized by their addictive behaviors regarding smartphone usage.

Little research has focused on the safety of smartphone-addicted users and on accidents in their everyday lives, although previous studies have shown that road/traffic accidents tend to occur when using cell phones while driving or walking. For instance, many studies have identified the negative effects of hand-held devices on visual behaviors (e.g., minimal glances at traffic lights), vehicle performance, reaction time, and reduction in speed (Alm & Nilsson, 1994; Harbluk, Noy, Trbovich, & Eizenman, 2007; Salvucci, Markley, Zuber, & Brumby, 2007). Moreover, such mobile technology can affect pedestrian safety through the impairment of looking behaviors and detection of roadside events or through the inability to maintain a certain direction while navigating obstacles (Byington & Schwebel, 2013; Lin & Huang, 2017; Schabrun, van den Hoorn, Moorcroft, Greenland, & Hodges, 2014). Although these studies did not investigate what types of accidents are related to smartphone addiction, they suggest that the use of mobile devices can cause distractions and trigger the occurrence of accidents. Based on the results of this study, smartphone-addicted users might be more prone to accidents, due to their inability to recognize potentially dangerous or unsafe conditions. One of the most important factors in accidents related to mobile device usage is dual- or multitasking (Weksler & Weksler, 2012). With smartphones now being capable of integrating various functions, it is common to see users focusing on multiple tasks (Brasel & Gips, 2011). For example, some users may be listening to music, watching a movie, or playing games, while simultaneously maintaining their social connections through SNS and performing other personal tasks (Ralph, Thomson, Cheyne, & Smilek, 2014). As stated earlier, users are also prone to using hand-held devices in potentially risky situations (O’Connor et al., 2013). As the recent term “smombie” (i.e., combination of smartphone and zombie) indicates, smartphone addiction not only denotes the excessive use of such devices but also addictive behaviors in which users are unintentionally absorbed into their phones and fail to focus on anything else (Kwon, Kim, Cho, & Yang, 2013). In this regard, they ultimately fail at multitasking and increase their risk of accidents using such devices in potentially dangerous situations.

With recent concerns about smartphone-related accidents, actions related to smartphone usage have been implemented in public by the stated countries. In the state of New Jersey (United States), city planners decided to anchor traffic lights to the road so that smartphone users can be more visually aware of the changing lights as they stare at their devices. In Chongqing (China), a walking lane was especially created for pedestrians glued to their smartphones. Finally, Korea initiated a pilot project in which safety signs were installed to warn the public about the danger of smartphone-related accidents (Benedictus, 2014; Chang, 2016; Duke & Montag, 2017).

In general, using smartphones while walking or driving leads the user’s eyes away from the real-world environment (Young, 2012), thereby reducing the detection of visual cues or information (e.g., causing visual distraction) (Lin & Huang, 2017). Moreover, the use of aural-related contents, such as listening to music, disrupting auditory signals, or aural cues, is crucial for judging one’s safety (e.g., causing auditory distraction) (Barton, Lew, Kovesdi, Cottrell, & Ulrich, 2013; Schwebel et al., 2012). The demanding manual process of using a smartphone also impairs a driver’s performance by removing one or both hands from the steering wheel (i.e., manual distraction) (Head, Helton, Russell, & Neumann, 2012). Finally, these three types of distractions can be accompanied by cognitive interferences that take the user’s mind off of his/her current activity (e.g., causing cognitive distraction) (Lennon, Oviedo-Trespalacios, & Matthews, 2017; Young, 2012). Furthermore, due to the multi-functioning features of smartphones, using a smartphone can concurrently produce these distractions, thereby increasing the risk of accidents (Shah, 2002; Young & Salmon, 2012).

This was the first exploratory study to examine the association between smartphone addiction and the occurrence of several types of accidents. The findings of this study support and extend the existing evidence by showing that smartphone-addicted users face increased risks of accidents that can occur in everyday life. However, several limitations should be considered. First, because of the cross-sectional study design, causality cannot be inferred. Second, the subject sample was limited to young adult university students. In this regard, adolescents are more vulnerable to smartphone addiction and they are more likely to walk instead of using any other means of transportation. However, elderly people may have weak cognitive and sensory functions. Thus, this demographic could make another group vulnerable to smartphone-related accidents. Third, it is difficult to analyze the different types of distraction mechanisms due to the lack of information regarding the contents accessed over smartphone during the accident and the location where the accident occurred. Furthermore, there is no information regarding no frequency of accidents. Fourth, since the number of participants was relatively small, the analysis was limited to a simple comparison of the different types of content accessed over smartphone. Hence, a future study should investigate the types of content assessed in direct relation with each accident. Fifth, the data included in this study were limited to determine the characteristics of the study population. As a result, it is impossible to rule out the possibility of unmeasured confounding. Finally, the status of smartphone addiction could be inaccurate, since it was likely to be under- or overestimated on the self-reported questionnaire. Therefore, psychoinformatics, a new discipline that uses digital technology and information science to develop the collection, organization, and synthesis of psychological data, can be helpful for predicting smartphone addiction and helping those affected by such addiction (Montag et al., 2016; Yarkoni, 2012).

In conclusion, this study showed that the smartphone-addicted university students were more likely to have experienced accidents. Furthermore, the findings highlighted the potential for future research to investigate whether using entertainment-related contents may be a crucial risk factor for accidents to occur. Although the results of this study must be validated and clarified through additional research, the findings have established an academic basis regarding accident risk among smartphone-addicted users.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (grant nos. 2015R1D1A1A01059048 and 2015R1D1A1A01057619). This work was also supported by the Education and Research Encouragement Fund of Seoul National University Hospital (2017).

Authors’ contribution

H-JK and J-YM planned this study, and K-BM managed this study. H-JK, J-YM, H-JK, and K-BM analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript, and J-YM finally reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alm H., Nilsson L. (1994). Changes in driver behaviour as a function of handsfree mobile phones – A simulator study. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 26(4), 441–451. doi:10.1016/0001-4575(94)90035-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton B. K., Lew R., Kovesdi C., Cottrell N. D., Ulrich T. (2013). Developmental differences in auditory detection and localization of approaching vehicles. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 53, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2012.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedictus L. (2014, September 15). Chinese city opens ‘phone lane’ for texting pedestrians. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/shortcuts/2014/sep/15/china-mobile-phone-lane-distracted-walking-pedestrians

- Benowitz N. L. (2008). Neurobiology of nicotine addiction: Implications for smoking cessation treatment. The American Journal of Medicine, 121(4), S3–S10. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J. (2012). Problematic use of the mobile phone: A literature review and a pathways model. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 8(4), 299–307. doi:10.2174/157340012803520522 [Google Scholar]

- Brasel S. A., Gips J. (2011). Media multitasking behavior: Concurrent television and computer usage. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(9), 527–534. doi:10.1089/cyber.2010.0350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky W., Slor Z. (2013). Background music as a risk factor for distraction among young-novice drivers. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 59, 382–393. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2013.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byington K. W., Schwebel D. C. (2013). Effects of mobile Internet use on college student pedestrian injury risk. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 51, 78–83. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M. C. (2016, June 27). Seoul puts up road safety signs to warn ‘smartphone zombies’. The Straits Times. Retrieved from http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/seoul-puts-up-road-safety-signs-to-warn-smartphone-zombies

- Chaparro A., Wood J. M., Carberry T. (2005). Effects of age and auditory and visual dual tasks on closed-road driving performance. Optometry and Vision Science, 82(8), 747–754. doi:10.1097/01.opx.0000174724.74957.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci K., Akgönül M., Akpinar A. (2015). Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(2), 85–92. doi:10.1556/2006.4.2015.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke É., Montag C. (2017). Smartphone addiction and beyond: Initial insights on an emerging research topic and its relationship to Internet addiction. In Montag C., Reuter M. (Eds.), Internet addiction (pp. 359–372). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46276-9_21 [Google Scholar]

- Haigney D., Westerman S. J. (2001). Mobile (cellular) phone use and driving: A critical review of research methodology. Ergonomics, 44(2), 132–143. doi:10.1080/00140130118417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbluk J. L., Noy Y. I., Trbovich P. L., Eizenman M. (2007). An on-road assessment of cognitive distraction: Impacts on drivers’ visual behavior and braking performance. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 39(2), 372–379. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2006.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head J., Helton W., Russell P., Neumann E. (2012). Text-speak processing impairs tactile location. Acta Psychologica, 141(1), 48–53. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R. J., van Egmond R., de Ridder H. (2016). Task prioritization in dual-tasking: Instructions versus preferences. PLoS One, 11(7), e0158511. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0158511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee I. K., Byun J. S., Jung J. K., Choi J. K. (2016). The presence of altered craniocervical posture and mobility in smartphone-addicted teenagers with temporomandibular disorders. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 28(2), 339–346. doi:10.1589/jpts.28.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Lee Y., Lee J., Nam J. K., Chung Y. (2014). Development of Korean Smartphone Addiction Proneness Scale for youth. PLoS One, 9(5), e97920. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. (2013). Exercise rehabilitation for smartphone addiction. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 9(6), 500–505. doi:10.12965/jer.130080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Jeong J. E., Cho H., Jung D. J., Kwak M., Rho M. J., Choi I. Y. (2016). Personality factors predicting smartphone addiction predisposition: Behavioral inhibition and activation systems, impulsivity, and self-control. PLoS One, 11(8), e0159788. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X., Xiong S., Zhu Z., Zheng S., Long G. (2015). Development of a conceptual framework for improving safety for pedestrians using smartphones while walking: Challenges and research needs. Procedia Manufacturing, 3, 3636–3643. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.749 [Google Scholar]

- Korean National Information Society Agency. (2011, November). Retrieved from http://www.nia.or.kr

- Kuss D. J., Griffiths M. D. (2011). Online social networking and addiction – A review of the psychological literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(9), 3528–3552. doi:10.3390/ijerph8093528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M., Kim D. J., Cho H., Yang S. (2013). The Smartphone Addiction Scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS One, 8(12), e83558. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M., Lee J. Y., Won W. Y., Park J. W., Min J. A., Hahn C., Gu X., Choi J. H., Kim D. J. (2013). Development and validation of a Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS). PLoS One, 8(2), e56936. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanaj K., Johnson R. E., Barnes C. M. (2014). Beginning the workday yet already depleted? Consequences of late-night smartphone use and sleep. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 124(1), 11–23. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.01.001 [Google Scholar]

- Lennon A., Oviedo-Trespalacios O., Matthews S. (2017). Pedestrian self-reported use of smart phones: Positive attitudes and high exposure influence intentions to cross the road while distracted. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 98, 338–347. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2016.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J., Lee S., Choi J., Joo S. (2016). The comparative study on travel behavior and traffic accident characteristics on a community road-with focus on Seoul Metropolitan City. Journal of the Korean Society of Civil Engineers, 36(1), 97–104. doi:10.12652/Ksce.2016.36.1.0097 [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. B., Huang Y. P. (2017). The impact of walking while using a smartphone on pedestrians’ awareness of roadside events. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 101, 87–96. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. H., Lin Y. C., Lee Y. H., Lin P. H., Lin S. H., Chang L. R., Tseng H. W., Yen L. Y., Yang C. C., Kuo T. B. (2015). Time distortion associated with smartphone addiction: Identifying smartphone addiction via a mobile application (App). Journal of Psychiatric Research, 65, 139–145. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant G. (2012). Mobile practices in everyday life: Popular digital technologies and schooling revisited. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 770–782. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01352.x [Google Scholar]

- Monacis L., de Palo V., Griffiths M. D., Sinatra M. (2017). Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 178–186. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C., Sindermann C., Becker B., Panksepp J. (2016). An affective neuroscience framework for the molecular study of Internet addiction. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1906. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasar J. L., Troyer D. (2013). Pedestrian injuries due to mobile phone use in public places. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 57, 91–95. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2013.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemme H. E., White K. M. (2010). Texting while driving: Psychosocial influences on young people’s texting intentions and behaviour. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(4), 1257–1265. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2010.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor S. S., Whitehill J. M., King K. M., Kernic M. A., Boyle L. N., Bresnahan B. W., Mack C. D., Ebel B. E. (2013). Compulsive cell phone use and history of motor vehicle crash. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(4), 512–519. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N., Lee H. (2014). Nature of youth smartphone addiction in Korea. Journal of Communication Research, 51(1), 100–132. doi:10.22174/jcr.2014.51.1.100 [Google Scholar]

- Radesky J. S., Kistin C. J., Zuckerman B., Nitzberg K., Gross J., Kaplan-Sanoff M., Augustyn M., Silverstein M. (2014). Patterns of mobile device use by caregivers and children during meals in fast food restaurants. Pediatrics, 133(4), 2013–3703. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph B. C., Thomson D. R., Cheyne J. A., Smilek D. (2014). Media multitasking and failures of attention in everyday life. Psychological Research, 78(5), 661–669. doi:10.1007/s00426-013-0523-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redelmeier D. A., Tibshirani R. J. (1997). Association between cellular-telephone calls and motor vehicle collisions. New England Journal of Medicine, 336(7), 453–458. doi:10.1056/NEJM199702133360701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen L. D., Whaling K., Carrier L. M., Cheever N. A., Rokkum J. (2013). The Media and Technology Usage and Attitudes Scale: An empirical investigation. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2501–2511. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvucci D. D., Markley D., Zuber M., Brumby D. P. (2007). iPod distraction: Effects of portable music-player use on driver performance. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.67.6357&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Google Scholar]

- Schabrun S. M., van den Hoorn W., Moorcroft A., Greenland C., Hodges P. W. (2014). Texting and walking: Strategies for postural control and implications for safety. PLoS One, 9(1), e84312. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwebel D. C., Stavrinos D., Byington K. W., Davis T., O’Neal E. E., de Jong D. (2012). Distraction and pedestrian safety: How talking on the phone, texting, and listening to music impact crossing the street. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 45, 266–271. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. (2002). U.S. Patent Application No. 10/144,807. [Google Scholar]

- Shin K., Kim D., Jung Y. (2011). Development of Korean Smartphone Addiction Proneness Scale for youth and adults. Seoul, South Korea: National Information Society Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Strayer D. L., Drew F. A. (2004). Profiles in driver distraction: Effects of cell phone conversations on younger and older drivers. Human Factors, 46(4), 640–649. doi:10.1518/hfes.46.4.640.56806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegmann E., Stodt B., Brand M. (2015). Addictive use of social networking sites can be explained by the interaction of Internet use expectancies, Internet literacy, and psychopathological symptoms. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 155–162. doi:10.1556/2006.4.2015.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weksler M. E., Weksler B. B. (2012). The epidemic of distraction. Gerontology, 58(5), 385–390. doi:10.1159/000338331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A. M., Cheung V. I., Ku L., Hung E. P. (2013). Psychological risk factors of addiction to social networking sites among Chinese smartphone users. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2(3), 160–166. doi:10.1556/JBA.2.2013.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarkoni T. (2012). Psychoinformatics: New horizons at the interface of the psychological and computing sciences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(6), 391–397. doi:10.1177/0963721412457362 [Google Scholar]

- Young K. L., Salmon P. M. (2012). Examining the relationship between driver distraction and driving errors: A discussion of theory, studies and methods. Safety Science, 50(2), 165–174. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2011.07.008 [Google Scholar]

- Young R. (2012). Cognitive distraction while driving: A critical review of definitions and prevalence in crashes. SAE International Journal of Passenger Cars – Electronic and Electrical Systems, 5(1), 326–342. doi:10.4271/2012-01-0967 [Google Scholar]